Abstract

Objectives To evaluate the nature, type and prevalence of potential drug–drug interactions (DDIs) in prescriptions dispensed in community pharmacies in Thessaloniki, Greece. Secondary objectives included the classification of DDIs as per pharmacotherapeutic class of the medications and the investigation of the relationship between medical specialties and the frequency of potential DDIs, as well as the relationship between DDIs and prescription size. Setting DDIs are a common cause of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) among patients using multiple drug therapy. In Greece a reliable computerized surveillance system for monitoring potential DDIs is not yet fully established. As a result, the prevalence of such DDIs in prescriptions dispensed by community pharmacies in Greece is unknown. Methods We conducted a prospective, descriptive study. Over a 3-month period (November 2007–January 2008), a total of 1,553 handwritten prescriptions were collected from three community pharmacies in Thessaloniki, Greece. The prescriptions were processed using the Drug Interactions Checker within the www.drugs.com database. The identified potential DDIs were categorized into two classes, major and moderate, according to their level of clinical significance. Main outcome measures Overall 213 prescriptions had one or more potential DDIs and a total of 287 major and moderate DDIs were identified. Potential DDIs were identified in 18.5% of all prescriptions. Major DDIs were identified in 1.9% of all prescriptions and represented 10.5% of all DDIs detected, whereas moderate DDIs were identified in 16.6% of all prescriptions and represented 89.5% of all DDIs detected. The rate of DDIs increased with prescription size. The most common drug involved in major DDIs was amiodarone which interacts with potassium-wasting diuretics, digoxin, simvastatin and acenocoumarol. Conclusions Our results indicate that patients in Greece are at risk of ADRs caused by medications due to potential DDIs. An appropriate surveillance system for monitoring such interactions should be implemented and physicians should be more aware of potentially harmful DDIs. Pharmacists can contribute to the detection and prevention of drug-related injuries, especially of clinically meaningful DDIs that pose a potential risk to patient safety.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Impact of findings on practice

-

There is a high prevalence of potential DDIs in prescriptions dispensed in community pharmacies in Greece.

-

Physicians such as psychiatrists, cardiologists and neurologists need to be more aware in order to avoid clinically meaningful DDIs than other medical specialties.

-

The implementation of an electronic surveillance system, which would provide pharmacists with the appropriate information to assess the degree of risk to the patient and to prevent potentially harmful DDIs, seems to be an effective action.

Introduction

Drug–drug interactions (DDIs) result in a modification of the action of one or more concurrently administered medications. DDIs are classified as pharmacodynamic or pharmacokinetic, and may result in increased or decreased efficacy, in treatment failure as well as in increased toxicity of medications [1, 2]. The problem is made even more complex by the concomitant use of over-the-counter medications and herbal remedies (e.g., St. John’s wort), certain types of food, ethanol and smoking. Although many DDIs exist, only a small part of these is clinically relevant [3–5]. Multiple drug treatment has been associated with the occurrence of DDIs, adverse drug reactions (ADRs), medication errors, and increased risk of hospitalization [6, 7] with several studies suggest that DDIs may be the cause of up to 3% of all hospital admissions [8–12]. Usually when multiple drug treatment is unavoidable, the potential benefits of drug combinations are weighted against the risk of the occurrence of a clinically significant DDI, taking into account the availability of alternatives.

Pharmacists play an important role in protecting the patients from the dangers posed by potential DDIs, especially with respect to drugs with a narrow therapeutic index [13]. Manual review of medications in a prescription can be performed by pharmacists, but the efficiency in the detection of DDIs is approximately 70% of DDIs in a two drug prescription, and the proportion decreases substantially as the number of medications increases [14]. By using computerized DDI screening programs we can significantly improve the identification of potentially harmful DDIs, beyond what can be achieved with manual review alone [15].

In Greece there is a lack of an effective screening system for detecting DDIs both at the level of prescribing by physicians and also at dispensing from community pharmacies. Almost all prescriptions are handwritten. Usually patient’s medication history can be accessed through manual observation of patient’s prescriptions book and all DDIs have to be identified manually. Although issues of improving primary health care and pharmaceutical care are of wide concern, due to the lack of DDIs monitoring systems, inappropriate prescription of drugs with potential DDIs causing serious risks to patients’ health has not been studied extensively [16–19]. Monitoring of potential DDIs may improve the quality of patient care [1].

Aim of the study

The objectives of this study were to evaluate the nature, type and frequency of potential DDIs in prescriptions dispensed from three community pharmacies in Thessaloniki, Northern Greece, during a 3-month period (November 2007–January 2008). Secondary objectives were the investigation of the relationship between specialty of prescribing physicians and the frequency of DDIs and to determine drug classes which were involved in potential DDIs.

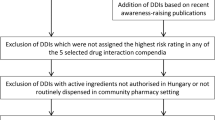

Methods

The major region of Thessaloniki was stratified into three geographical areas, according to different population groups, including urban and rural regions, which are represented the city’s population. Following randomization, three community pharmacies (one from each geographical area) were selected in order to obtain a representative sample of the population of community pharmacies of Thessaloniki. All 1,553 prescriptions dispensed in these three community pharmacies through a 3-month period (November 2007–January 2008) were collected. Each participating pharmacist, following oral consent by the patient, removed all personal data from each prescription, including patients’ name, address and insurance information. The information collected included age, gender, date of the prescription, diagnosis, specialty of the prescribing physician, name of the medications in each prescription, dosage and quantity of medications dispensed.

Potential DDIs were detected using the Drug Interactions Checker within www.drugs.com database [20]. Furthermore, all medications were classified according to The Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System with Defined Daily Doses (ATC/DDD) [21]. The detected DDIs were classified as major, moderate and minor, depending to their severity of clinical significance and cross-over checked manually for the presence of enough published scientific evidence for the identified interacting agents [1, 22]. Major interactions are either well documented and have the potential of being harmful to the patient, or have a low incidence of occurrence (and perhaps limited documentation) and have the potential of serious adverse outcome. Moderate interactions are of moderate clinical significance, are less likely than major interactions to cause harm to the patient, or are less well documented. Minor interactions are of minor clinical significance. These interactions, regardless of the degree of their documentation, are least significant because of limited risk to the patient [23]. Due to interpatient variability, an interaction labeled as major may produce no harmful effects in some patients, while a moderate interaction may cause significant adverse effects. Only major and moderate DDIs were further analyzed statistically using Microsoft Access® and Microsoft Excel®.

Results

A total of 3,853 medications were prescribed to 1,553 prescriptions dispensed in three community pharmacies in Thessaloniki, Greece, during a 3-month period (November 2007–January 2008). The average number of medications per patient was found to be 2.5 (range 1–9). Of the 1,553 prescriptions 416 (26.8%) had only one medication and the remaining 1,137 prescriptions (73.2%) had two or more medications.

Prescriptions with two or more medications were checked for potential DDIs both electronically and manually [20, 22]. DDIs identified were classified as major and moderate, according to their level of clinical significance. In 213 prescriptions (13.7% of all prescriptions) at least one major or moderate DDI was identified and the total number of interactions was found to be 287 (18.5% of all prescriptions). Of these 287 DDIs, 30 were major (1.9% of all prescriptions corresponding to 10.5% of all interactions) and the remaining 257 DDIs (16.6% of all prescriptions corresponding to 89.5% of all interactions) were moderate (Table 1).

Of the 30 major DDIs, 20 cases involved pharmacodynamic interaction and 10 cases involved pharmacokinetic interaction. Major DDIs were identified in prescriptions of patients with chronic diseases. The most frequent diagnosis was found to be coronary heart disease. The higher ratio (%) of major DDIs in relation to the number of prescriptions written from each medical specialty was observed by psychiatrists (6.6%), followed by cardiologists (5.0%), neurologists (4.7%), general practitioners (2.0%), primary care physicians (1.4%) and orthopaedics (1.3%; Fig. 1). The most frequent major DDIs identified in the prescriptions are given in Table 2. The ratio of DDIs/number of prescriptions increased with the number of medications prescribed per patient (Fig. 2).

Medications that were involved in major DDIs belonged to several ATC system groups: 58.3% of them were agents acting on the cardiovascular system (ATC: C) 23.3% were agents acting on the nervous system (ATC: N) and 18.3% of the drugs were agents acting on other systems.

Discussion

The present study revealed that the overall incidence of potential DDIs in prescriptions dispensed in community pharmacies in Northern Greece was 18.5%. The identified DDIs were classified according to their severity [23], as major (the interaction may be life-threatening and/or require medical interventions to minimize or prevent serious adverse effects) and moderate (the interaction may result in an exacerbation of the patient’s condition and/or require an alteration in therapy). The prevalence of the major DDIs was 1.9% of all prescriptions dispensed (10.5% of all DDIs), whereas the prevalence of the moderate DDIs was 16.6% of all prescriptions dispensed (89.5% of all DDIs). Similar findings have been reported in several studies from other countries [24, 25]. Our findings clearly show that the ratio of potential DDIs/number of prescriptions is directly proportional to the number of medications prescribed per patient, in accordance with the results of previous studies [25].

Most potential DDIs were recognised in prescriptions written by cardiologists, primary care physicians and general practitioners. These physicians usually prescribe a greater number of medications per prescription than others. In the present study the most common major DDI was between ACE inhibitors (e.g., ramipril) or angiotensin II receptor antagonists (e.g., irbesartan) with potassium-sparing diuretics (e.g., amiloride) [26]. Some specific drugs were strongly associated with clinically relevant DDIs, such as amiodarone which interacted with a wide range of prescribed medications, including potassium-wasting diuretics (e.g., furosemide and hydrochlorothiazide) [27], digoxin, HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (e.g., simvastatin) and coumarin anticoagulants (e.g., acenocoumarol) [28, 29].

The results give an indicative picture of the problem of DDIs in prescriptions dispensed in community pharmacies in Greece and demonstrate the need for the use of an improved reliable screening system for DDIs. Currently, all Greek pharmacies are equipped with computer software for dispensing medication, and therefore adding a drug-interaction utility to that software seems feasible in the near future. A larger study with more community or hospital pharmacies may give more reliable results. The use of electronic prescriptions, bar codes to assist in the identification of patients and their medications, the implementation of an accurate system providing novel scientific evidence, as well as careful selection of medication, are some of the suggestions strongly recommended nowadays to physicians [30–36]. Moreover, pharmacists have a key role in identifying and preventing potential DDIs in prescriptions dispensed to patients [37]. In order to improve surveillance of DDIs, several computer-based programs which recognize and warn about potential DDIs have been developed and evaluated [2, 38, 39]. However, several studies have demonstrated the inconsistency and overall limited reliability of DDI screening software to warn dispensing pharmacists of potential serious DDIs [40]. Often there is conflicting information among the various drug interaction compendia because classification of the severity of potential DDIs is not always straightforward. Therefore, the implementation of computer software capable of detecting DDIs at community or hospital pharmacies has not obviated the need for pharmacists to have a solid understanding of DDIs.

Limitations of this study were related to a certain degree of underreporting of potential DDIs because DDIs were detected only within one handwritten prescription and not reflecting a history, as well as without taking into account over-the-counter medications and herbal preparations (e.g., St. John’s wort) which may contribute to DDIs.

Conclusion

The main outcome of this descriptive study is that prescriptions dispensed in community pharmacies in Greece revealed a high frequency of DDIs in prescribed medications. In particular, patients on multiple drug therapy for cardiovascular diseases and patients receiving antidepressant medications should be closely monitored for adverse outcomes from potential DDIs. Identifying and preventing potentially harmful DDIs is a critical component of a pharmacist’s mission and the role of pharmacist should be shifted from drug-oriented to patient-oriented. Physicians especially psychiatrists, cardiologists, neurologists, primary care physicians and general practitioners, and pharmacists must remain vigilant in their monitoring of potential DDIs and make appropriate dosage or therapy adjustments. The implementation of a computer-based electronic system, which would provide pharmacists with the appropriate information to assess the degree of risk to the patient and to prevent an adverse outcome as a result of exposure to the interacting drugs, seems to be an appropriate action.

References

Hansten PD, Horn JR. Drug Interactions Analysis and Management, Facts & Comparisons. Philadelphia, PA:Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009. ISBN: 10: 1-57439-311-8.

Becker ML, Kallewaard M, Caspers PW, Schalekamp T, Stricker BH. Potential determinants of drug–drug interaction associated dispensing in community pharmacies. Drug Saf. 2005;28:371–8.

Linnarsson R. Drug interactions in primary health care: a retrospective database study and its implications for the design of a computerized decision support system. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1993;11:181–6.

Bergendal L, Friberg A, Schaffrath A. Potential drug-drug interactions in 5.125 mostly elderly out-patients in Gottenburg, Sweden. Pharm World Sci. 1995;17:152–7.

Merlo J, Liedholm H, Lindblad U, Bjorck-Linne A, Falt J, Lindberg G, et al. Prescriptions with potential drug interactions dispensed at Swedish pharmacies in January 1999: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2001;323(7310):427–8.

Colley CA, Lucas LM. Polypharmacy: the cure becomes the disease. J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8:278–83.

Bjerrum L, Andersen M, Petersen G, Kragstrup J. Exposure to potential drug interactions in primary health care. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2003;21:153–8.

Jankel CA, Fitterman LK. Epidemiology of drug-drug interactions as a cause of hospital admissions. Drug Saf. 1993;9:51–9.

Huic M, Mucolic V, Vrhovac B, Francetic I, Bakran I, Giljanovic S. Adverse drug reactions resulting in hospital admission. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1994;32:675–82.

McDonnell PJ, Jacobs MR. Hospital admissions resulting from preventable adverse drug reactions. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36:1331–6.

Peyriere H, Cassan S, Floutard E, Riviere S, Blayac JP, Hillaire-Buys D, et al. Adverse drug events associated with hospital admission. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37:5–11.

Becker ML, Caspers PW, Kallewaard M, Bruinink RJ, Kylstra NB, Heisterkamp S, et al. Determinants of potential drug–drug interaction associated dispensing in community pharmacies in the Netherlands. Pharm World Sci. 2007;29:51–7.

Abarca J, Colon LR, Wang VS, Malone DC, Murphy JE, Armstrong EP. Evaluation of the performance of drug-drug interaction screening software in community and hospital pharmacies. J Manag Care Pharm. 2006;12:383–9.

Weideman RA, Bernstein IH, McKinney WP. Pharmacist recognition of potential drug interactions. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56:1524–9.

Glassman PA, Simon B, Belperio P, Lanto A. Improving recognition of drug interactions: benefits and barriers to using automated drug alerts. Med Care. 2002;40:1161–71.

Tzimis L, Katsantonis N, Leledaki A, Vasilomanolakis K, Kafatos A. Prescribed medication and nutrition of social care patients in Crete, Greece. Public Health. 1996;110:361–7.

Tzimis L, Katsantonis N, Leledaki A, Vasilomanolakis K, Kafatos A. Antibiotics prescription for indigent patients in primary care. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1997;22:227–35.

Tzimis L, Kafatos A. Drug utilization and health behaviours among indigent elderly patients in Crete, Greece. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 1999;8:105–14.

Antonakis N, Xylouri I, Alexandrakis M, Cavoura C, Lionis C. Seeking prescribing patterns in rural Crete: a pharmacoepidemiological study from a primary care area. Rural Remote Health. 2006;6:488.

Drug Interactions Checker, Cerner Multum, Inc., Denver, CO. http://www.drugs.com/.

ATC/DDD Index. WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology, Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Oslo, Norway. 2009. http://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_Index/.

Hansten PD, Horn JR. The top 100 drug interactions: a guide to patient management. Freeland, WA: H & H Publications. LLP; 2009. ISBN 978-0-9819440-0-5.

Hansten PD, Horn JR. Drug interactions & updates. 7th ed. Vancouver, WA: Applied Therapeutics Inc.; 1992. ISBN-10: 0-8121-1381-0.

Cruciol-Souza JM, Thomson JC. A pharmacoepidemiologic study of drug interactions in a Brazilian teaching hospital. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2006;61:515–20.

Janchawee B, Wongpoowarak W, Owatranporn T, Chongsuvivatwong V. Pharmacoepidemiologic study of potential drug interactions in outpatients of a university hospital in Thailand. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2005;30(1):13–20.

Chiu TF, Bullard MJ, Chen JC, Liaw SJ, Ng CJ. Rapid life-threatening hyperkalemia after addition of amiloride HCl/hydrochlorothiazide to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;30:612–5.

Antonelli D, Atar S, Freedberg NA, Rosenfeld T. Torsade de pointes in patients on chronic amiodarone treatment: contributing factors and drug interactions. Isr Med Assoc J. 2005;7:163–5.

Roten L, Schoenenberger RA, Krahenbuhl S, Schlienger RG. Rhabdomyolysis in association with simvastatin and amiodarone. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:978–81.

Siddoway LA. Amiodarone: guidelines for use and monitoring. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:2189–96.

Astrand B, Montelius E, Petersson G, Ekedahl A. Assessment of ePrescription quality: an observational study at three mail-order pharmacies. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2009;9:8.

Murphy JE, Malone DC, Olson BM, Grizzle AJ, Armstrong EP, Skrepnek GH. Development of computerized alerts with management strategies for 25 serious drug-drug interactions. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2009;66:38–44.

Cusack CM. Electronic health records and electronic prescribing: promise and pitfalls. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2008;35:63–79.

Jani YH, Ghaleb MA, Marks SD, Cope J, Barber N, Wong IC. Electronic prescribing reduced prescribing errors in a pediatric renal outpatient clinic. J Pediatr. 2008;152:214–8.

Rupp MT, Warholak TL. Evaluation of e-prescribing in chain community pharmacy: best-practice recommendations. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2008;48:364–70.

Venkatraman R, Durai R. Errors in medicine administration: how can they be minimised? J Perioper Pract. 2008;18:249–53.

Carroll NV. Do community pharmacists influence prescribing? J Am Pharm Assoc. 2003;43:612–21.

Heikkila T, Lekander T, Raunio H. Use of an online surveillance system for screening drug interactions in prescriptions in community pharmacies. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62:661–5.

Tamblyn R, Huang A, Perreault R, Jacques A, Roy D, Hanley J, et al. The medical office of the 21st century (MOXXI): effectiveness of computerized decision-making support in reducing inappropriate prescribing in primary care. CMAJ. 2003;169:549–56.

Vonbach P, Dubied A, Krahenbuhl S, Beer JH. Evaluation of frequently used drug interaction screening programs. Pharm World Sci. 2008;30:367–74.

Hazlet TK, Lee TA, Hansten PD, Horn JR. Performance of community pharmacy drug interaction software. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash). 2001;41:200–4.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the pharmacists of the three community pharmacies for their assistant during the study.

Funding

None.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chatsisvili, A., Sapounidis, I., Pavlidou, G. et al. Potential drug–drug interactions in prescriptions dispensed in community pharmacies in Greece. Pharm World Sci 32, 187–193 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-010-9365-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-010-9365-1