Abstract

Objective

The objective of the study was to develop and test standards of practice for handling non-prescription medicines.

Method

In consultation with pharmacy registering authorities, key professional and consumer groups and selected community pharmacists, standards of practice were developed in the areas of Resource Management; Professional Practice; Pharmacy Design and Environment; and Rights and Needs of Customers. These standards defined and described minimum professional activities required in the provision of non-prescription medicines at a consistent and measurable level of practice. Seven standards were described and further defined by 20 criteria, including practice indicators. The Standards were tested in 40 community pharmacies in two States and after further adaptation, endorsed by all Australian pharmacy registering authorities and major Australian pharmacy and consumer organisations. The consultation process effectively engaged practicing pharmacists in developing standards to enable community pharmacists meet their legislative and professional responsibilities.

Main outcome measures

Community pharmacies were audited against a set of standards of practice for handling non-prescription medicines developed in this project. Pharmacies were audited on the Standards at baseline, mid-intervention and post-intervention. Behavior of community pharmacists and their staff in relation to these standards was measured by conducting pseudo-patron visits to participating pharmacies.

Results

The testing process demonstrated a significant improvement in the quality of service delivered by staff in community pharmacies in the management of requests involving non-prescription medicines. The use of pseudo-patron visits, as a training tool with immediate feedback, was an acceptable and effective method of achieving changes in practice. Feedback from staff in the pharmacies regarding the pseudo-patron visits was very positive.

Conclusion

Results demonstrated the methodology employed was effective in increasing overall compliance with the Standards from a rate of 47.4% to 70.0% (P < 0.01). This project led to a recommendation for the development and execution of a national implementation strategy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Impact of findings on practice

-

Significant improvement in the quality of service delivery in the management of requests involving non-prescription medicines.

-

Provision of commonly accepted and recognised standards and protocols for the management of requests involving non-prescription medicines in community pharmacy.

Introduction

Medicines in Australia are either not subject to classification (i.e. no restriction on sales), e.g., Gaviscon liquid, pharmacy medicines (Schedule 2, or S2), e.g., ranitidine tablets, pharmacist only medicines (Schedule 3, or S3), e.g., salbutamol inhalers, and prescription medicines (Schedule 4, or S4). Pharmacy medicines are only available at a pharmacy where pharmacist advice and intervention are available. Pharmacist Only medicines must be stored out of reach of general public, the pharmacist must hand the medicine to the consumer and he/she (the pharmacist) is required to communicate with the consumer.

The classification of medicines is intended to provide reasonable consumer access to medicines for self-medication, while providing protection from possible harm associated with misuse of potent medicines. Legislation concerning pharmacy medicines, which may only be sold in pharmacies or by registered poisons sellers, relates to matters of supply, packaging, labeling, and storage. The underlying assumption of the legislation is that pharmacists will monitor sales and intervene where necessary to ensure people use medicines safely, appropriately and effectively. Legislation concerning pharmacist only medicines requires pharmacists to be active participants in their sale, and addresses matters of labeling and recording.

Community pharmacy practice

Community pharmacists are an important source of primary health care advice. They are easily accessible and positively valued by consumers [1–3]. However, while most pharmacy staff provide quality services and advice, according to consumers, actual practice varies widely [4–6]. Some Australian and overseas studies [3, 7] have indicated, where pharmacists are involved in discussions with consumers about health advice or medicine use, high quality advice and decisions follow. Canadian and Australian studies [3, 8, 9] indicate, although nearly half of all customer requests relate to conditions involving the upper respiratory tract, pharmacists provide advice and opinion on a wide variety of conditions and symptoms. In over 80% of all instances in these studies, pharmacists provided advice and or sold a product, and in approximately 10% of cases, pharmacists made direct referrals to general practitioners.

Despite Australian legal requirements in relation to physical facilities required in pharmacies and in relation to storage and sale of scheduled medicines, little attention has been paid to the development of comprehensive national standards, standard operating procedures, policies and practice protocols against which practice can be audited and the quality of service to consumers assured. Based on previous research, it was anticipated that increased pharmacist accessibility and advice promulgating with the national standards, potentially would lead to improved health outcomes [3].

Changing practice

There is substantial evidence that providing information and/or advice in isolation does not result in a change in practice [10]. Additionally, consistent with theoretical models of behavior change [11, 12] and program implementation [13], it is widely acknowledged that efforts to change health professional performance must be targeted and involve a wide range of strategies to lead to substantial improvements in professional practices [14]. Standards, although an essential tool in developing and maintaining quality practice, do not of themselves appear to ensure such practice. Research has shown application of a quality improvement model involving a continuing spiral of setting standards, providing training and educational materials, assessment, providing feedback, learning and reassessment has the potential to change health care provider performance [5, 6, 15, 16].

de Almeida Neto et al. demonstrated that pseudo-patron visits accompanied with immediate feedback provide effective tools for facilitating behavior change in dealing with non-prescription medicines in community pharmacy and reinforcing systems of quality practice [5, 6]. Pseudo-patron methodology involves an individual entering the health care setting, not to seek treatment, but to observe the health care process. Behavioral theorists have found practice results in more effective learning and skills retention when spread over successive days rather than concentrated in a workshop session [5, 6, 17]. Further, reinforcement and feedback are considered necessary to optimise skill transfer from workshops to the practice setting [5, 6, 18].

Objective

This study aimed to develop and test a set of national standards that would promote a structured approach to the assessment of consumer requests for medication or advice, and increase pharmacist accessibility and provision of advice. The project used as a starting point, existing standards, guidelines and policy papers [19–23]. Guidelines prepared for the Australian context gave helpful insights into directions the profession wished to take, but were insufficiently detailed to enable effective audit. The Entry Standards for General Practices of the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners [22] were chosen as the most helpful model and used as a template for producing a set of standards for the pharmacy profession.

Method

The work was conducted in compliance with the requirement of the human research universities ethics committees of the institutions. An amended form of Participatory Action Research (PAR) was the principal methodology for the research. It was a preferred methodology for circumstances in which a new practice is being developed and implemented in the workplace alongside current ongoing work practices [24].

This approach was effective in assisting a group of individuals to manage a complex problem. Common techniques in this approach are information and knowledge feedback from individuals, allowing the group to decide on the way forward and iterative review by individuals [24].

A Project Reference Group, consisting of representatives of all key stakeholder groups, provided advice and had direct input to revisions of preliminary drafts of the standards and formulated the final version following feedback from practitioners and organisations. The research was further informed by previous research in pharmacy practice that demonstrated that sustained behavior change in pharmacy requires not only training in the required behaviors but also on-going on-site feedback and coaching to consolidate the new skills in practice [5, 6]. In this previous research feedback and coaching was provided after pseudo-patron visits which involves a person unknown to pharmacy staff (pseudo-patron) entering the pharmacy and requesting a specific product or general advice. The visit takes place at any time within a given time frame. The pseudo-patron is trained to follow a standard script then leave the pharmacy and report on the interaction to a researcher and/or educator.

In this project, consultation was the principle process employed in the development of standards process. The testing process employed audit and pseudo-patron visits within a 7-week multiple baseline design. This involved a series of repeated measures across several variables to assess the effectiveness of the training program on the practice behavior of pharmacy staff in community pharmacies [25]. Scenarios were developed and selected at random for each pseudo-patron visit.

Research design

The project comprised four phases:

-

1.

Problem definition

-

2.

Devising solutions

-

3.

Preliminary test of solutions

-

4.

Re-testing and refining solutions.

Phases one, two and three involved the development and preliminary testing of a draft set of standards, standard operating procedures and practice protocols (‘the Standards’) that had broad acceptance by the profession, consumers and government. Phase four involved re-testing (trial implementation) of the Standards in a sample of community pharmacies, revision of the Standards in response to results, leading to final endorsement of the Standards by pharmacy registering authorities, the profession and consumer groups (Fig. 1).

The Standards document

The final Standards document comprised:

-

1.

An Introduction: providing background to development of the Standards, a description of the document structure, suggestions for an assessment process, and a glossary of terms.

-

2.

The Standards: described under four main sections. A summary of what is contained in the Standards themselves is shown in Table 1. The standards define and describe what professional activities are required in the provision of pharmacist only and pharmacy medicines at a consistent and measurable level of practice. The standards are followed by criteria, which are clearly defined processes describing how each standard is achieved in practice. They describe key components of the standard and specify the appropriate level of performance required by expressing what a competent professional would do in terms of observable ‘outputs’. Each criterion is followed by a number of indicators which assist in deciding the degree to which an individual criterion has been met. These are of central importance and describe the processes (inputs) which, when delivered consistently, indicate the achievement of a criterion.

-

3.

Appendices: Six appendices were provided:

-

Self-Audit schema

-

Standard Operating Procedures relating to particular criteria

-

Policy regarding confidentiality

-

Policy regarding documentation procedures

-

Practice Protocols relating to product request and symptom presentation for both pharmacists and pharmacy assistants

-

Suggestions for effective ways of gaining consumer feedback

-

List of information resources

The Standard Operating Procedures and policies were drafted by the researchers during the development and testing processes. The Practice Protocols are those developed by the University of Sydney’s Pharmacy Practice Department. The consumer feedback instruments were developed by consumer consultants who conducted focus groups with pharmacy staff and consumer representatives near the end of the project.

An example of one of the Standards is shown in Table 2

Phase four: re-testing solutions

Participants

A convenience sample of 40 pharmacies (20 in SA and 20 in NSW) willing to participate in an implementation pilot trial (phase four) was identified. The main impetus for selecting a convenience sample was to understand issues surrounding the handling of non-prescription medicines relevant to standards of practice without the need to generalise precisely to the entire population. Pharmacies were chosen from a list of pharmacies that were known to the researchers and to provide a reasonable representation of different styles and locations of community pharmacies in Australia. Thus urban and rural pharmacies, independent pharmacies and those belonging to a buying group, pharmacies in small local shopping groups of shops and those in large shopping centers were selected. Both pharmacists and pharmacy assistants, from each participating pharmacy, took part in the project.

A reference group comprising of practicing community pharmacists was established in each State to assist with the recruitment process. Participants of this reference group were selected by the researchers and comprised of community pharmacists who were recognised by their peers as being model professionals. A cross section of practice types was conveniently sampled for inclusion in the trial implementation process. The 20 South Australian pharmacies were located within the Adelaide metropolitan region and surrounding country areas and of the 20 pharmacies from New South Wales, 10 were located across Sydney and 10 in Orange and Bathurst combined (regional centers approximately 260 km from Sydney). Initial contact was by telephone and an explanation of the project provided. Further information describing the project was faxed/mailed to the pharmacy.

Re-testing procedures

Compliance with the Standards was assessed via an auditing process, and practice behavior in relation to the Standard Operating Procedures and Protocols was monitored via pseudo-patron visits.

Audits

Pharmacies were audited on the Standards at baseline (week 1or 2), mid-intervention (week 5) and post-intervention (week 7). As the Standards were designed as an auditable document, they were used directly as a data collection instrument for each audit.

A scoring system was developed to quantitatively evaluate change in compliance with the Standards over the three data collection points. Independent scores for compliance with the indicators and criteria were calculated. If the indicator/criterion was met, a score of one was issued.

Pseudo-patron visits

Each participating pharmacy received 10 pseudo-patron visits. Baseline measures comprised four visits, and post-intervention measures consisted of six visits. Following the baseline visits, participants attended a training session on communication techniques and application of the Standard Operating Procedures and Protocols. Visits post-training were accompanied by immediate feedback and coaching delivered by an educator (researcher) with the aim of encouraging appropriate behavior changes. All educators were community pharmacists with many years of experience.

Pseudo-patron visits were audio-taped to increase data reliability. Following the visit, the educator listened to the tape-recorded interaction and transcribed the data to a standardised data collection sheet. Following baseline visits, this sheet was also used to assist with the provision of individualised feedback to pharmacy staff.

A scoring system quantitatively evaluated behavior change in Protocol and Standard Operating Procedure application for pharmacists and pharmacy assistants. This system was based on operationally defining components of the Protocol and issuing a score (two for ‘met’; one for ‘partially met’; 0 for unmet) for each component. An overall score was then calculated by tallying participants’ compliance with the operational definition of individual component behaviors. This enabled a quantitative measure of overall behavior change and the identification of the degree of change in pharmacists and pharmacy assistants individually and across different scenarios, highlighting areas of difficulty.

Separate analyses were undertaken for each of the six scenarios used for the pseudo-patron visits. Each pharmacy was audited on four of the six scenarios at baseline, chosen at random. Following training, each of the scenarios was delivered to participating pharmacies once, randomly selected.

Training program

Training comprised two forms:

-

Two evening training sessions. The first provided background information on the project, outlined the Standards and encouraged participants to implement the Standards in their practices. The second provided information on communication techniques, and developed skills in applying the Protocols and Standard Operating Procedures in the practice environment. Communication skills were practiced these are described elsewhere [6]. The concept of pseudo-patron visits was presented and the role the visits would play in providing ongoing, onsite, individualised training was explained. One pharmacy withdrew from the project prematurely following the training evenings.

-

Ongoing onsite training in the form of pseudo-patron visits followed by feedback and coaching was conducted at individual pharmacies.

Data analysis

All data input, formatting and analysis were performed using the SPSS-PC 7.5 version of the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS). Frequency distributions were produced to obtain descriptive data on participants’ changes in compliance with the Standards and changes in adherence with the Protocols and Standard Operating Procedures over time. Normality tests were conducted to determine appropriate methods of data analysis. As the audit data were not normally distributed, Friedman test was used to evaluate the statistical significance of changes in compliance with the Standards over time. The pseudo-patron visit data were normally distributed. Therefore, Repeated Measures Analysis of Variance was used to evaluate the statistical significance of changes in participants’ adherence with the Protocols and Standard Operating Procedures over time.

Results

Compliance with Standards: audit visits

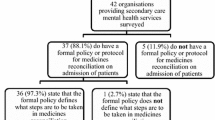

Overall compliance with all criteria for each point in time was calculated by tallying the number of criteria met by each pharmacy and dividing that figure by the total number of criteria each pharmacy was assessed upon. The median score for all pharmacies for each point in time is shown below (Fig. 2).

There was a significant increase in criterion compliance over time (Fig. 2). Median scores increased from a baseline of 47.4% (IQR 40–52.6%) to 60% (IQR 50–70%) at midpoint (P < 0.01). Similarly the difference between baseline and endpoint 70% (IQR 50–78.9%) scores was significant (P < 0.01). However, changes in practice behavior were seen to plateau between midpoint and endpoint and were not significant.

Changes in participants’ compliance over time with each individual criterion defined in the Standards are reported in Table 3.

Pseudo-patron visits

A total of 390 pseudo-patron visits were made to pharmacies in the project. Of these, 156 were conducted during baseline, and 234 post the training evenings.

There was a statistically significant change in the average mean score for overall adherence with the protocols at baseline for all participating pharmacies (score 27.0%, SD 14.1%) compared to a score of 50.3% (SD 13.2%) post-intervention (p < 0.01).

The average mean score at baseline for scenario 1 was 13.4% (SD 16.9%), this can be compared to a score of 47.1% (SD 23.4%) post-intervention. A statistically significant difference in protocol adherence was found between the two time periods (P < 0.01).

Scenario 2 scores were similar to those of Scenario 1 at baseline (10.6%, SD 13.8%). However, post-intervention changes were not as marked, with a score of 25.3% (SD 22.4) calculated. This change was not significantly different at the 1% level (P = 0.011).

Scenario 3, with an outcome of pharmacy assistant/symptom request/S2 treatment scored higher on baseline measures (32.4%, SD 18.4%) than scenario 1 and 2 which were direct product requests. A significant difference was found between baseline and post-intervention (50.16%, SD 22.2%) scores (P < 0.01).

Scenarios one, two and three were targeted at pharmacists assistants (Fig. 3). Scenarios four, five and six were pharmacist targeted (Fig. 4). Baseline scores ranged from 26.3% (SD 17.9%) for scenario 5, to 41.2% (SD 15.9) for scenario 6 and 47.7% (SD 15%) for scenario 4. These can be compared to post-intervention measures of 44.5% (SD 21.4%) for scenario 5, 59.9% (SD 15.2%) for scenario 4 and 70.7% (SD 20.5%) for scenario 6.

Significant differences were found between baseline and post-intervention scores for scenarios five and six (P < 0.01). However, scores pre- and post-intervention were not significantly different for scenario four at the 1% level (P = 0.028).

Discussion

The process of Standards development (phases one, two and three) utilised a powerful consultation process through the pharmacy network.

Results were consistent with research that shows that application of a quality improvement model involving a continuing spiral of setting standards, providing training and educational materials, assessment, providing feedback, learning and reassessment has the potential to change health care provider performance [5, 6, 15, 16].

The consultation processes and the method employed in the re-testing process (phase four) was effective in developing practice standards that were acceptable to pharmacy staff and key stakeholder groups and in increasing overall compliance with the Standards from a rate of 47.4% to 70.0% (P < 0.01). The use of pseudo-patron visits, as a training tool with immediate feedback, was an acceptable and effective method of achieving changes in practice. Feedback from staff in the pharmacies regarding the pseudo-patron visits was very positive.

Results across all scenarios indicated the provision of a training program and tools such as Standard Operating Procedures and Protocols led to a significant improvement in performance. This improvement could relate to the selection procedure, which biased the sample towards pharmacists willing to allow observation of their practice, and hence likely to be motivated towards change. Reasonably, pharmacies with greater scope for improvement could see even more impressive results.

After two intensive training sessions, pharmacists and their assistants were asked to take their training back to the pharmacy and pass on their knowledge to all staff. The timelines inappropriately foreshortened this process. This is reflected in the relatively small increase in number of pharmacies achieving compliance between the mid-intervention audit and the final audit.

Conclusion

The Standards developed for the provision of pharmacist only and pharmacy medicines were demonstrated to be achievable within the context of contemporary community pharmacy in Australia. In addition, they have been accepted in principle as the benchmark of professional practice by professional organisations, consumers and government. The broad acceptability of the Standards and the implementation program utilised suggest this is a practical approach that could be taken to all pharmacies in Australia, and indeed, beyond. The 40 pharmacies involved in the project may not be representative of all practices in Australia but they did comprise of a wide range of pharmacies. It is important to note that while the pharmacists were highly supportive of this initiative, they all recognised that the whole profession needs to be involved. In addition, it is also important to note that this was not a cost-benefit study. Subsequent research has carried out a cost-benefit analysis of the Standards [26].

References

Lam P, Krass I. Prescription-related counselling - What information do you offer? Aust Pharm 1995;14:342–7.

Mott K, Eldridge F, Gilbert A, March G, Lawson T, Vitry A, et al. Consumer needs and expectations of community pharmacy. 2005. Report prepared for the Pharmacy Guild of Australia by the Quality Use of Medicines and Pharmacy Research Centre. Date accessed 27/06/06 http://beta.guild.org.au/research/project_display.asp?id = 284

March G, Gilbert A, Roughead E, Quintrell N. Developing and evaluating a model for pharmaceutical care in Australian community pharmacies. Int J Pharm Pract 1999;7:220–9.

Anon. Can you rely on your pharmacist? Consumer (magazine of the New Zealand Consumers’ Institute) 1996;(346):6–9.

de Almeida Neto AC, Benrimoj SI, Kavanagh DJ, Boakes RA. Novel educational training program for community pharmacists. Am J Pharm Educ 2000;64:302–7.

de Almeida Neto AC, Benrimoj SI, Kavanagh DJ, Boakes RA. A pharmacy-based protocol and training program for non-prescription analgesics. J Soc Adm Pharm 2000;17:183–92.

Lobas NH, Lepmski PW, Abramowitz PW. Effects of pharmaceutical care on medication costs and quality of patient care in an ambulatory-care clinic. Am J Hosp Pharm 1992;49:1681–2.

Poston J, Kennedy R, Waruszynski B. Initial results from the Community Pharmacist Intervention Study. Can Pharm J 1995;127:18–25.

Stewart K, Garde T, Benrimoj SI. Over the counter medication sales in community pharmacy - A. Direct product requests and symptom presentation. Aust J Pharm 1985;66:979–82.

Kanouse DE, Jacoby I. When does information change practitioners’ behaviour? Int J Technol Assess Health Care 1988;4:27–33.

Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986. ISBN 013815614X.

Prochaska JO, Di Clemente CC. Towards a comprehensive model of change. In: Miller WR, Heather N, (editors). Treating addictive behaviours. Plenum, New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1986. ISBN 0306422484.

Winett RA, King AC, Altman DG. Health psychology and public health: an integrative approach. New York, NY: Pergamon; 1989. ISBN 008033640X.

Oxman A, Thomson M, Davis D, Haynes R. No magic bullets: a systematic review of 102 trials of interventions to improve professional practice. Can Med Assoc J 1995;153:1423–31.

Thomson MA, Oxman AD, Davis DA, Haynes RB, Freemantle N, Harvey EL. Audit and feedback to improve health professional practice and health care outcomes. In: Cochrane Collaboration (editor). Cochrane Library. Issue 3. Oxford, UK: Update Software; 1998.

Krska J, Kennedy E. An audit of responding to symptoms in community pharmacy. Int J Pharm Prac 1996;4:129–35.

Skeff K, Berman J, Stratos G. A review of clinical teaching improvement methods and a theoretical framework for their evaluation. In: Edwards J, Marier R, (editors). Clinical teaching for medical residents. New York, NY: Springer; 1988. ISBN 0826156002.

de Almeida Neto AC. Changing pharmacy practice: the Australian experience. Pharm J 2003;270:235–6.

The Canadian National Association of Pharmacy Regulatory Authorities. National Standards of Practice for Schedule II and Schedule III Drugs, 1995.

The New Zealand Ministry for Health. Draft statement of expectations of the pharmacist in the sale of OTC medicines, 1995.

The Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. Statement on the delivery of pharmacy (S2) and pharmacist only (S3) medicines within community pharmacies, 1997.

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Entry standards for general practices, 1996.

Pharmacy Guild of Australia. Quality care standards for Australian pharmacies. Deakin ACT, 1998.

Linstone H, Turoff M. The Delphi method: techniques and applications. In: Linstone HA, Turoff M, editors. New Jersy’s Science and Tecnology University, 2002.

Herson M, Barlow D. Single-case experimental designs: strategies for studying behaviour change. New York, NY: Pergammon Press; 1976. ISBN 0080195113.

Benrimoj SI, Emmerton L, Taylor R, Williams K, Gilbert A, Quintrell N, et al. A cost-benefit analysis of pharmacist only (S3) and pharmacy medicines (S2) and risk-based evaluation of the Standards. June 2005. Report prepared for the Pharmacy Guild of Australia by the University of Sydney. Date accessed 18/10/06 http://beta.guild.org.au/research/project_display.asp?id = 246

Acknowledgement

Funding for this project was obtained from the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing through the 3rd Community Pharmacy Agreement Research and Development Program.

Conflicts of Interest Professor Benrimoj and Dr de Almeida Neto have been involved with professional pharmacy organisations in Australia, which may have an interest in the development of standards of practice for the provision of non-prescription medicines.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Benrimoj, S.(.I., Gilbert, A., Quintrell, N. et al. Non-prescription medicines: a process for standards development and testing in community pharmacy. Pharm World Sci 29, 386–394 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-007-9086-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-007-9086-2