Abstract

This study aims to illuminate the phenomenon of learning outcomes. Although a wide range of studies in education have examined the phenomenon in various ways, few have investigated how scholars themselves conceive of it. To provide insight into this issue, the paper explores the following questions: How is the term “learning outcome” defined? By whom? When? Where? The investigation is based on a document analysis of a selection of 33 scholarly written documents in which the concept is discussed. Findings indicate that there is a dominant established definition of the term learning outcome. However, a wide range of alternative definitions are also identified. These assert that learning outcomes involve more than what can be described in pre-specified and measurable terms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Today a paradigm shift is said to be underway, characterised by a change in emphasis from teaching to student learning (Adam 2004; Shepard 2000; Ewell 2005). From a historical viewpoint, with regard to quality, primary focus has been placed on input indicators such as student numbers and fiscal measures. But for a number of years now, the traditional input-oriented curriculum has been criticised as being overly focused on the teacher instead of the learner (Kellaghan and Greaney 2001). In order to achieve greater focus on the learner more precision in curriculum design is called for. This gives rise to the need to express, through the medium of learning outcomes, anticipated learning after completion of courses or modules (Ewell 2005). This in turn affects educators at every level within educational systems that are implementing learning outcomes.

In the case of Norway, this is visible in the government’s educational reforms of the past 10 to 15 years.Footnote 1 The Norwegian term “læringsutbytte” (more or less equivalent to “learning outcomes” in English) is widely used and covers a variety of aspects of learning and assessment at nearly every level and for various purposes. Norwegian policymakers seem to be striving to create an educational system where the emphasis on learning outcomes is high at the attentive level and in terms of results. However, there appears to be a lack of clarity surrounding these issues, and practitioners are left with crucial questions: What is meant by the term learning outcome? And what are learning outcomes to be used for?

These questions are not new on the international scene, and several theories have been developed to address them. Adam (2004) points out that although there may seem to be a common understanding of learning outcomes within a broader framework, when it comes to practical application “there are possibly confusions between learning outcomes, objectives and aims” (Adam 2004:19). This issue and related ones are debated by a long list of scholars (Allan 1996; Davies 2002; Hussey and Smith 2003; James and Brown 2005; Ewell 2005; Buss 2008; Hussey and Smith 2008; Nusche 2008; Spady 1988; Spady and Marshall 1991; King and Evans 1991; Brady 1996; Capper and Jamison 1993; Hargreaves and Moore 2000; Jessup 1991; Burke 1995). Nevertheless, MacBeath and Moos (2009:2) assert that the intrinsic values and purposes of outcomes have been insufficiently questioned and analysed.

It appears that a study on learning outcomes as discussed and problematised by scholars within the fields of education and educational research would be appropriate here, as these scholars play a key role in defining, discussing and problematising educational concepts. Their twofold role as constructors of the concept of learning outcomes and employees within educational systems where the concept is being implemented makes them a particularly interesting object of study. Their diverse voices as expressed in scholarly written documents may provide deeper insight into the phenomenon of learning outcomes.

This article is organised in three parts. The first part contains a presentation of the applied analytical approach, a short historical overview and a description of the framework for the investigation. In the second part the methodological design and procedure are described. The second part also contains the findings of the investigation. In the third and final part the findings are discussed and some concluding remarks are made.

2 Analytical approach

From a social constructivist standpoint, language can be said to have a constitutive role in institutional reality. As an extension of this, statements concerning learning outcomes as expressed in scholarly written documents can be said to have a constitutive role when it comes to what is considered as real and true about the concept of learning outcomes. Against this background, J. R. Searle (1995) has articulated an analytical approach that enables identification of understood functioning of an agreed-upon definition, or lack thereof.

According to Searle (1995:14), members of a collective impose a certain status on a phenomenon as an institutional fact, which also gives the phenomenon a certain function through agreement and acceptance. Searle describes institutional facts as facts dependent on human agreement, such as money, property, government and marriage, which all require human institutions for their existence. These are the opposite of brute facts, which exist independently of human thinking, for example elements of nature such as the sun, mountains, stones, trees etc. In situations where the members of a collective do not agree upon and accept a phenomenon’s status and function, the phenomenon (either as a new phenomenon or as continued acceptance of a phenomenon) ceases to exist. Searle points out that this is crucial, particularly when it comes to property rights, national identification or the designation of a military leader in a revolution.

In the context of this paper, the phenomenon of learning outcomes is considered an institutional fact dependent on a collective such as a university, a community, or a national educational system. A highly relevant example in this context is the European Qualifications Framework,Footnote 2 one of several international efforts to define a common ground for understanding learning outcomes. The phenomenon of learning outcomes is given a certain status and function by the members of the collective through agreement and acceptance. To make a rather extreme case, systems of examination for providing students with credentials at the conclusion of a programme are dependent on society’s acceptance, trust and confidence to be viable. In a situation where the collective does not agree on or accept the system of examination the whole concept of credentials and certification for further education and employability would probably collapse. However, the lack of acceptance of or agreement on the use of learning outcomes would most likely not have such dramatic consequences.

According to Searle, a collective’s agreement on giving a specific phenomenon a particular status and function can be expressed with the logic rule “X counts as Y in context C”. This study investigates a selection of authors within education and educational research and their understanding of the phenomenon of learning outcomes (X) as expressed in scholarly written documents and what they consider learning outcomes to “count as” (Y) within their particular context (C).

3 The origin of learning outcomes

The history of the term “learning outcome” is short and can be traced back to the past century. It is closely linked to the history of another highly relevant term within the field of curriculum development—“objective” (Eisner 2005; Allan 1996; Ewell 2005; Jessup 1991; Burke 1995). The fact that the two terms are often intertwined and interconnected in the literature makes it difficult to distinguish between them. Allan (1996) describes the use of learning outcomes as a minefield of terminological confusion.

In the outcome literature, the term learning outcome is said to be anchored in the “objectives movement” at the beginning of the past century as well as in the theories on “mastery learning” and the works of Benjamin Bloom of the 1950s. The development of the concept of learning outcomes is described as a linear process, starting with the objectives movement, continuing through the mastery learning theories, before ending up in today’s outcome-based education movement (King and Evans 1991; Spady and Marshall 1991; Brady 1997).

Robert Gagné (1974) and Elliot Eisner (1979) have each made key contributions to the discussion on learning outcomes. According to Gagné, a learning outcome “makes possible a refined understanding of the learning process and thus permits a drawing of relatively precise implications for the design of instruction” (1974:51). Eisner writes that learning outcomes are “essentially what one ends up with, intended or not, after some form of engagement” (1979:101). Gagné is recognised as a behaviourist (Burke 1995), while Eisner is considered a pragmatist and social constructivist (Allan 1996). Hence, Gagné and Eisner represent two different perspectives on learning which are accompanied by different perspectives on the outcomes of learning. Their approaches are also quite different and this has naturally influenced their contributions. The late Gagné was concerned with instructional design and interested in determining the kind of learning required to accomplish certain tasks involving planning and sequencing (Burke 1995:59). Eisner is concerned with the role of curriculum in learning and has defined a “trichotomy of outcomes”. According to Eisner, outcomes are partly dependent on the student, partly on the subject in question and partly on the teacher. This makes it impossible to sort all learning into pre-specified terms (Allan 1996).

Ewell (2005) identifies another approach involving the development of explicit “learning objectives”, which dates back to the early 20th century in the USA and elementary and secondary education based on the work of John Dewey and others within the “pragmatist movement”. In the USA this was followed by a diverse range of “competency-based” college programmes during the period of massification of higher education in the 1960s and early 1970. According to Ewell (2005), these colleges featured narrative transcripts in place of grades and periodic demonstration of student performance assessed on the basis of established criteria for all relevant levels of ability.Footnote 3

Yet another approach to learning outcomes has emerged, which uses the attainment of defined learning outcomes as a measure of institutional effectiveness (Ewell 2005). This is part of the “assessment movement” that started in the mid-1980s with government calls to examine the effectiveness of funding allocated to public institutions (Ewell 2005). Biesta (2009:34) adds that “the school effectiveness and improvement movement has played an important role in the idea that education can and should be measured.”

The concept of learning outcomes may be defined in a myriad of ways due to different perspectives on learning and various purposes for working with outcomes.

4 Framework of the investigation

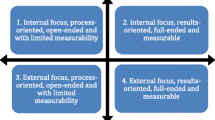

A framework for this investigation was developed in order to apply Searle’s logic rule. Gagné and Eisner’s different theoretical perspectives on learning provided a suitable point of departure, as their definitions of learning outcomes may be viewed as two opposite poles of a continuum where learning outcomes are either characterised as process-oriented, open-ended and with limited measurability (Eisner) or result-oriented, full-ended and measurable (Gagné). The continuum represents a range of “learning orientations” potentially possessed by the authors of the selected publications.

Looking at the history of the term learning outcome, it is apparent that there are different conceptions of the purpose of learning outcomes as well. These fall into two main groups: learning outcomes are either perceived as a tool for educational and instructional planning and curriculum development or as a tool for measuring effectiveness and accountability. These groups may also be viewed as two opposite poles of a continuum of “purpose orientations” along which the authors’ definitions of learning outcomes will possibly range.

Again, looking back at the history, it is obvious that the various definitions encompass both an orientation of learning and of purpose. For this study the two orientations were combined into the model below which serves as the analytical framework for the investigation. The model illustrates the crossing of the two axes (continuums) which creates four quadrants of combinations of orientation (see Fig. 1).

The opposite poles of the learning orientation continuum (the horizontal axis) are represented by the characteristics process-oriented, open-ended and limited measurability versus result-oriented, full-ended and measurable. Meanwhile, one pole of the purpose orientation continuum (the vertical axis) is defined as educational and instructional planning and curriculum development, and the opposite as accountability, respectively. In this context the term “accountability” comprises political accountability, legal accountability, bureaucratic accountability, professional accountability and market accountability (Darling-Hammond 2004).

The model provides a basis for a matrix with four quadrants of combinations of learning orientation and purpose orientation, which in turn provides a starting point for the investigation into the term learning outcome as defined by scholars in a selected number of publications. The ambition of this study is to analyse the definitions according to the scholars’ learning orientation and purpose orientation, instead of merely collecting definitions.

5 Methodology and selection of publications

This study examines a selection of publications from the 1970s to today that address the concept of learning outcomes. Due to the fact that this concept is relatively young, the knowledge base encompasses definitions of learning outcomes found in traditional academic publications as well as in scholarly documents with a developmental purpose, such as working papers and reports. Care has been taken when selecting the publications to ensure a balance between high-quality publications and highly-relevant documents that are part of current scholarly debate. Because the purpose of this paper is to present the perceptions of the term learning outcome held by scholars it is important to describe how the material was selected. There is a large amount of literature that uses the term without focusing on the term itself—these have been excluded. Only publications that take an empirical or analytical approach to the phenomenon of learning outcomes were eligible for selection. The publications were chosen expressly for this paper and to facilitate the investigation into how the concept of learning outcomes is defined and discussed among scholars. The label “scholar” refers to individuals with an academic education, working in academia and performing scholarly work based on principles and practices used by scholars. Nevertheless, not all of the authors of the selected publications necessarily fulfil all of these requirements, for example they may be performing scholarly work, only not in academia. The selection varies from articles published in traditional peer-review journals to more practice-oriented journals, books, working papers and reports—but all share a certain degree of citation. In fact it became more and more evident throughout the investigation that the documents more or less represent a web of scholars citing each other in one way or another. The search could have been limited to peer-reviewed articles to ensure a certain academic standard. However, following the citation paths revealed that several of the most referenced publications were not found in peer-review journals although they were written by scholars. It became clear that some of the voices most often heard in the ongoing debate were found outside the sphere of formal academic publishing. To be able to include these, a broader search method was applied. The selection was not made with the ambition of fully covering all relevant literature on the subject. An effort was made, however, to include literature of major relevance to the research question, as well as literature at the heart of current scholarly debate. Focus was also placed on the quality of the selected literature in terms of peer review and number of citations.

Most of the publications have been selected from the research platform ISI Web of Science,Footnote 4 the online digital library ERIC,Footnote 5 and the online digital database Source OECD.Footnote 6 Two search queries have been used: learning outcomes and outcomes of learning. The search queries resulted in more than 10,000 hits in the ISI Web of Science. After narrowing the search to “articles” on “Education and Educational research” in “English”, the number of hits was reduced to 1,228. By reading abstracts of articles in the ISI database, the number of articles was cut down considerably, to 28, using the above-mentioned criteria. Several publications were also chosen on the basis of citations in already-selected publications. A few publications were only available on the Internet via Google.com. A total of 33 publications were selected between September 2008 and September 2009.

Table 1 presents an overview of the selection of publications, by source, spread and type of publication. The column “spread of publications” shows that 20 publications were selected on the basis of an exploratory “blind search” using the search queries learning outcomes and outcomes of learning. The search queries did not match publications discussing learning outcomes in lower education to an adequate degree; therefore, four books and nine additional publications were chosen to strategically support the selection.

It is important to be aware of the differences between authors when it comes to thematic focus. Some discuss learning outcomes from the standpoint of their own profession, such as medicine, teacher education or sociology (Harden et al. 1999; Reese 2004; Cochran-Smith 2001; Wagenaar 2002). Others discuss learning outcomes from the perspective of having implemented learning outcomes as a tool at their institution or preparing for such implementation (Otter 1992; Wilson et al. 2000; Nusche 2008; Moon 2005). Yet others examine the concept within a political and/or ideological framework (Hussey and Smith 2003; 2008; Smyth and Dow 1998; Hargreaves and Moore 2000; Malan 2000). There are also differences between those who debate specific theories of learning outcomes such as outcome-based education theories (Spady and Marshall 1991; Spady 1988; Brady 1997; Furman 1994) and those who discuss learning outcomes in a specific context such as higher education, lower education or vocational education (Allan 1996; Burke 1995).

6 Categorisation as an instrument

The process of gathering and extracting information from written documents can be done in different ways (Gall et al. 1996). The approach used in this study shares similarities with document analysis and literature review techniques. As the study seeks to identify perspectives and conceptions held by writers through their textual statements concerning one particular term, strong focus was placed on textual contributions describing the term. The selected publications were read thoroughly several times, with special focus on statements on learning outcomes.

A reading guide with different categories was developed based on the previously described analytical framework to help to maintain focus and facilitate the process of reading and extracting information in a systematic way. The reading guide contains categories aimed at identifying the “Y” and the “C” in Searle’s logic rule (“X count as Y in context C”). The following categories were used for gathering data about the context (“C”): author’s name, type and title of publication, year published, study approach and author’s country of work. Additional categories for extracting data about what learning outcomes “count as” (“Y”) such as statements on learning outcomes, learning orientation and purpose orientation were developed as well. Data was extracted from the documents via statements and descriptions that illustrated the authors’ perspectives.

The data collected consists of data that requires text interpretation. Certain issues must be taken into consideration when using a qualitative approach to interpreting the meaning of a text as the meaning resides in the minds of the writer and readers. Thus the meaning can change from reader to reader and from one historical period to another (Gall et al. 1996). Gall et al. (1996) emphasise how important it is for text interpreters to study the context in which the text was produced—the author’s purpose in writing it, the author’s working conditions, the author’s actual and intended audience and the audience’s purpose for reading the text. In addition the qualitative researcher also must “reali[s]e that, in reading the text, she creates her own meanings” (Gall et al. 1996). The study discussed in this paper has its limitations, and it has not been possible to fulfil the requirements of Gall et al. completely. Nevertheless, a certain amount of knowledge regarding the author’s purpose and intended audience was available, as they were mentioned in the articles or described in the different journals’ “scope and means”. There is, however, always a possibility that the investigator misunderstood or misinterpreted the meaning of the text.

7 Findings I: Purpose and learning orientations

This section addresses the three categories of investigation: purpose orientation, learning orientation and definition of learning outcome used. These categories aim at identifying the “Y” in Searle’s logic rule, i.e. what learning outcomes “count as” in the selected material.

7.1 Purpose orientation

Three sub-categories were created for the document analysis of the conceptions of purpose of learning outcomes as set out in the analytical framework: one for educational and instructional planning and curriculum development, one for accountability, and one for both purposes. The first covers scholars that discuss the phenomenon of learning outcomes mainly as a tool for educational and instructional planning and curriculum development. The second encompasses a wide range of issues concerning different types of accountability, from legal accountability to professional accountability.

All the authors discuss the phenomenon of learning outcomes within the framework of a purpose orientation. The spread of purpose orientation among the 33 publications in the selection reveals some interesting differences between them. Most of the writers primarily view learning outcomes as a tool for educational and instructional purposes (17). Only three authors consider them mainly as a tool for accountability purposes. However, if the number of publications that are accountability-oriented is added to the number of publications that examine the phenomenon of learning outcomes for both purposes it is evident that about half of the selected publications discuss learning outcomes in terms of accountability as well (13). Also it is important to underline that the authors’ understanding of accountability varies depending on the type of accountability they consider relevant to their discussion.

7.2 Learning orientation and definitions of learning outcome

The definitions used by the authors of the selected publications give some indication of how they perceive the concept of learning outcomes. Therefore, examining how they define and describe the phenomenon is the first step towards categorising their learning orientation.

Looking at the category definitions of learning outcome used it is apparent that almost all the publications contain a definition of the term learning outcome. Some authors provide nuanced explanations of their definition, while others borrow definitions from other authors and build their definition upon these. Yet others define learning outcome on the basis of what it is not, using established definitions for comparison. This study is not primarily concerned with whether an individual author accepts or rejects the phenomenon of learning outcomes. The objective is to investigate how the authors describe and understand the phenomenon. In the context of this paper, an author’s stated perspective on learning outcomes is considered to be his or her understanding. Several of the authors define the term learning outcome in a certain way, before criticising it and proposing an alternative definition. In these cases the alternative definition is considered to be their understanding. In other cases where the author is critical but no alternative is proposed, the author’s description of learning outcome is considered to be his or her understanding of the concept.

For the purpose of this investigation the definitions of learning outcome were clustered into two broad groups based on common features: established definitions and alternative definitions. As a result it is possible that certain definitions were not given full justice. However, the intention here is to identify specific patterns rather than provide comprehensive descriptions of all the definitions.

7.3 Established definitions

In the context of this study, established definitions refer to definitions that primarily describe the term learning outcome as result-oriented, full-ended and measurable (in keeping with Gagné’s definition). These definitions are often historically rooted in or share similarities with basic ideas from behaviourism, the objectives movement, the curriculum planning movement, or the mastery learning movement. The definitions often posit that a learning outcome is a written statement of intended and/or desired outcome to be manifested by student performance. The formulation of learning outcomes and the establishment of criteria for assessing (formative and summative) attainment of predefined learning are essential characteristics of this cluster. The definitions also bear a strong resemblance to one another in the way they are formulated. This is not the case with the alternative definitions.

7.4 Alternative definitions

Alternative definitions of the term learning outcome are often the result of a critique of established definitions. The authors make an effort to describe and build a logic for their alternative definitions rooted in more open-ended perspectives on learning such as cognitive, constructivist, and sociocultural theory. One key conviction held by these writers is that all learning cannot be reduced to written pre-specified statements of learning outcomes. Another is that it is impossible to cover all learning by pre-specified learning outcomes and thereby impossible to measure all learning. Although these definitions share the same main convictions they are formulated in significantly different ways (Table 2).

To sum up, certain scholars’ understanding of—or perspective on—the term learning outcome is grounded in or reflects ideas from the objectives and curriculum planning movements and behaviourist theories. Meanwhile, other scholars’ understanding—or perspective—is based on a critique of this approach. These authors often present an alternative definition rooted in constructivist and/or sociocultural approaches to learning. All the authors’ definitions are linked to a notion of purpose. Learning outcomes are viewed as either a tool for educational, instructional and curriculum purposes or a tool for accountability purposes. Some of the authors see learning outcomes as two-dimensional, i.e. covering both purposes.

7.5 Matrix of learning orientation and purpose orientation

The selected publications have been placed in a matrix based on the model presented earlier to determine whether there is a dominant perspective on learning outcomes or if there are several competing perspectives. The placement of the publications provides an indication of the scholars’ primary orientation when defining and describing the concept of learning outcomes (Fig. 2).

The matrix reveals three main groups of orientations. According to the authors grouped in the upper left quadrant, learning outcomes are open-ended, flexible and process-oriented, and used as a tool for educational and instructional purposes. According to the authors grouped in the upper right quadrant, learning outcomes are stated in full-ended, pre-specified and measurable terms, and used as a tool for educational and instructional planning and curriculum development purposes. The smaller group of authors in the lower right quadrant posits that learning outcomes are stated in full-ended, pre-specified and measurable terms, and used for accountability purposes.

The matrix does not indicate the strength of the author’s views on learning orientation and purpose orientation because it does not chart the publications’ distance to the centre of the model. Each axis represents a continuum of orientations, so the distance between one author and another may be a relatively long even though they have been placed within the same quadrant.

8 Findings II: Context and characteristics

To get a picture of the writer’s context and characteristics, categories were created for country of work, year published, level within the educational system concerned and study approach. The categories aim at identifying the “C” in Searle’s logic rule, i.e. the characteristics of the context within which learning outcomes are defined.

Table 3 indicates that learning outcomes are mainly discussed by authors in Anglo-Saxon countries. It is not, however, unlikely that this is due to the method used to select publications, which limited searches to English-language articles. On the other hand, this could be a result of policy development in the countries concerned. Anglo-Saxon countries have been addressing the issue of learning outcomes for many more years than continental European countries. The selected publications were published during the course of a 34-year period, from 1974 to 2008. When the spread of publishing year for all the publications is clustered into four-year periods it is clear that the largest number of publications was published in the period 1991–2005 (see Diagram 1).

Looking at the spread of publishing year for the two most highly represented countries in the selection of publications it is apparent that they had different peaks of publication. In the USA most of the publications were published during the period 1991–1995, as opposed to the UK where 2001–2005 was the peak period of publication. This suggests that the Anglo-Saxon discussions on learning outcomes are not necessarily one and the same.

Table 3 also presents an overview of the selected publications according to the level of the educational system the authors are investigating. The majority of the literature discusses the phenomenon of learning outcomes from the standpoint of lower education (16 publications). Thirteen authors discuss the phenomenon of learning outcomes in higher education, while four publications analyse them in a general perspective. There is a somewhat similar spread in the two most highly represented countries, although the UK has the largest number of publications addressing the phenomenon from the standpoint of higher education (nine out of 14 publications).

Moreover, Table 3 presents the study approach mentioned in the publications. Most of the publications discuss the phenomenon based on an analytical approach (23 publications). Only six publications are based on empirical evidence. However, if the number of publications that use an empirical approach is added to the number of publications that discuss both approaches it makes a total of 10 publications.

There is a possibility that the two peak periods for the American (1991–1995) and British (2001–2005) publications represent a high water mark in the debates in the two countries. To investigate this further the contextual settings, as described in the publications from the peaking periods, have been studied. An extract of this can provide a hint of the dominant policy environment in each country at the current time.

The American publications have the highest peak in the period 1991–1995. All of the four publications published within this period discuss the issue of OBE (outcome-based education) primarily from the view of lower education. According to the publications, the background for this attention is the popularity surrounding the phenomenon (Capper and Jamison 1993; Furman 1994; Spady and Marshall 1991; King and Evans 1991). The popularity is explained in different ways. OBE is described as being promoted by its advocates as a means of meeting every student regardless of environment, ethnicity, economic status or disabling condition (Capper and Jamison 1993: 428; Furman 1994:417). Three forces are particularly indicated as having contributed to the popularity: 1) in the past decade many states and districts have had success in student learning, 2) regional and state policy-making bodies (including the 1991 National Goals for America`s schools) demanded improved student outcomes and placed outcomes at the centre of major efforts to improve all aspects of schooling, and 3) central educational leaders and their calls for a new restructured system played a role (Spady and Marshall 1991:67). Furman reports that success stories of a variety of positive outcomes for OBE have had apparent pedagogical power and that its popularity is also explained as a response to a current accountability climate in education (1994: 417).

The British publications have the highest peak in the period 2001–2005. Five out of six publications within the period discuss learning outcomes from the perspective of higher education. The last one is a study of research on learning outcomes (James and Brown 2005). “Learning outcomes have been used extensively throughout the UK since the early 1990s” (Adam 2004:17). During the 1980s and early 1990s different national qualification frameworks were implemented or piloted in the UK. These actions were part of a comprehensive reform of post-compulsory education. The key objective of the reform was “…to empower all members of an increasingly diverse population to lead fuller lives in a rapidly changing world” (Burke 1995). In 1997 the national Committee of Inquiry into Higher Education (the Dearing report) portrayed a situation of mass participation in higher education. As a consequence of this the committee pronounced a need for clearer information about the courses and qualifications, explicit standards and levels of achievement required for different awards (Adam 2004:17). The UK Quality assurance Agency (QAA) monitors the effectiveness and whether HEIs achieve intended learning outcomes. Adam (2004) points out that learning outcomes therefore have direct links to standards, national mechanisms for quality assurance and the enhancement of teaching, learning and assessment.

In many ways the main goals for working with learning outcomes in the two countries seem to be grounded on the same overarching objectives: more and better learning for all. On the other hand the debate displayed through the publications gives a glimpse of quite different issues being addressed.

9 Discussion

The findings indicate that there are two main debates on the issue of learning outcomes. The dominant debate centres on whether learning and the outcomes of learning can and should be stated in full-ended, stable, pre-specified and measurable terms or in open-ended, flexible terms with limited opportunities for measurement. The dispute between the classical perspectives of Eisner (1979) and Gagné (1974) continues to this day. Discussions between authors who promote established definitions of the term learning outcome and those who propose alternative definitions are ongoing and no definitive conclusions have been reached.

A less dominant but equally important debate focuses on learning outcomes as a tool for accountability purposes. While many governments are in the process of establishing accountability-oriented educational systems, scholars primarily seem to view learning outcomes as a tool for educational and instructional planning and curriculum development. This may be natural for those who work with educational issues on an everyday basis, but perhaps there is a general perception that accountability is not an issue of concern to scholars. Studies of quality assurance within higher education have shown that faculty members tend to consider newer forms of quality assurance as a concern of others and an administrative task (Stensaker et al. 2008:221; Stensaker 2003). In their discussions on accountability and learning outcomes, Brady (1996), Furman (1994) and Cochran-Smith (2001) point out that there is more to accountability than government attempts to improve the effectiveness of and control over public funding. They posit that there has been too little focus on professional accountability as opposed to bureaucratic accountability. Both Furman (1994) and Cochran-Smith (2001) ask why professionals within education have not explored and defined their own purpose orientation of learning outcomes and created their own outcomes questions. “If we do not take control of framing the outcomes questions, then the outcomes questions will surely frame us and undermine our work as teachers, teacher educators, researchers and policymakers committed to a democratic vision of society and to the vital role that teachers and teacher educators play in that vision” (Cochran-Smith 2001:544).

Another issue of concern is cultural differences in conceptions of learning outcomes. The findings indicate that most of the publications selected for this study were written by authors in Anglo-Saxon countries, especially the UK and the USA. There is a question of whether it is possible—or right—to simply adopt one or two definitions of the term learning outcome which have been formulated for and within another contextual setting. Brady (1996) points out that an adoption of a mastery learning model involving the teaching of structural hierarchical units with frequent testing would be unlikely in Australia because of the country’s constructivist ethos and the lack of a strong behaviourist tradition. Nevertheless, since the time Brady’s article was published, the rhetoric of learning outcomes has been implemented in Australia, at least at the government level.Footnote 7 In Norway the concept of learning outcomes has been given a more prominent place in the ruling discourse of educational policy during the past 10 years. This is true for both higher and lower education, even though the country does not have a tradition of behaviourist or objective-based schooling. On the contrary, the Norwegian educational system was long dominated by the theories of John Dewey and the progressive movement (Telhaug et al. 2006). A recent evaluation of the implementation of the latest reform in lower education and training in Norway has revealed enthusiasm among teachers and school owners (municipalities and counties)—and problems, especially with comprehending and practicing a “new assessment regime” following the implementation of a competency-based curriculum (Møller et al. 2009). Working with outcomes illuminates issues of assessment and brings with it the danger of valuing what is measured rather than engaging in measurement of what we value (Biesta 2009:43). For this reason, Biesta (2009:44) emphasises the importance of keeping purpose a central issue in educational discussions. There is a question of whether countries should take their time to investigate the concept of learning outcomes and other countries’ experiences, and to consider why (for what purpose) they would want to implement them. Hargreaves and Moore point out that the greatest failing of the outcome-based approach is its reliance on technical rationality (2000:41). In their view, outcome-based education holds progressive potential for redistributing, redefining and realising new forms of school knowledge to the benefit of all students in some places. Still, they believe that more evidence on outcomes in various contexts is needed if a meta-analysis of outcomes and their effects in different policy contexts is to be developed.

9.1 Concluding remarks

To return to John R. Searle and his logic of collective intentionality “X counts as Y in the context of C”: Has this investigation made it possible to identify the unknowns “Y” and “C”?

When it comes to characteristics of the context (“C”), the main findings indicate that the phenomenon of learning outcomes has primarily been discussed by authors in Anglo-Saxon countries during the past 34 years. These findings may not be completely accurate due to the fact that one of the central search queries was English-language. Then again, these findings could properly reflect that Anglo-Saxon education policies have historically been more oriented towards learning outcomes than continental European policies have been.

Another interesting finding is that the discussion on learning outcomes in the two most highly represented countries (the UK and the USA) hit their peak at different times. (There is a 10-year interim between the peaks.) In addition, there appear to be slight differences in the level of the educational system the publications address. Taken together, these findings suggest that the discussions on learning outcomes in Anglo-Saxon countries are not necessarily one and the same.

When it comes to the question of what learning outcomes “count as” (“Y”), there appears to be a dominant established definition of the term learning outcome (Adam 2004). This study has shown that there are also a range of alternative definitions which share a common message: learning outcomes cannot be reduced to full-ended, stable and pre-specified measurements of student performance. Considering this divergence of opinion, there are grounds to discuss whether learning outcomes are actually an “institutional fact” as defined by Searle. Answering this question would require a much more thorough investigation and is a topic for future study.

This situation of competing perspectives is a cause for concern in a broader perspective as it is accompanied by the risk that when educational researchers and administrators discuss the phenomenon of learning outcomes, misunderstandings may arise or consensus may be reached on the basis of the wrong assumptions.

The linguistic factor of the English language as the prime language in the international scholarly debate concerning learning outcomes may represent a barrier for less dominant voices in non-English-speaking countries to be heard. This may overshadow linguistic nuances in how the term is being defined, discussed and understood as well as differing and important cultural and historical aspects that could enrich the debate. As an example the Norwegian government is introducing the term learning outcomes (læringsutbytte) through the implementation of a loosely-defined national qualification framework in higher education, and a national competency-based curriculum in lower education. In both cases the responsibility for transforming the chosen policy into practice is given to the higher education institutions and the school owners (counties and communities) within a decentralised lower education system. Few guidelines have been given on how to conduct the implementation. This means that much of the Norwegian debate concerning what learning outcomes actually are is held locally. As such Norway may represent an interesting example of the implementation of a concept inspired by an Anglo-Saxon approach, further explored and developed by practitioners with a long tradition of process-oriented learning. What this may lead to is yet to be seen.

The definitional power of learning outcomes on what is valued as important and appreciated as learning also needs to be taken into account. Different perspectives on learning imply different values, as do different orientations towards learning outcomes. Attentiveness to the dominant perspective and orientation is essential to open debate on what constitutes valuable learning.

Notes

The Quality Reform in Higher Education and the Knowledge Promotion reform in compulsory and upper secondary education and training, level 1–13 (www.kd.dep.no).

The EQF was adopted by the European Parliament and Council on 23 April 2008. The core of the EQF are eight reference levels describing what a learner knows, understands and is able to do—‘learning outcomes’. Levels of national qualifications will be placed at one of the central reference levels, ranging from basic (Level 1) to advanced (Level 8). It will therefore enable much easier comparison between national qualifications and should also mean that people do not have to repeat learning if they move to another country. The EQF encourages countries to relate their qualifications systems or frameworks to the EQF by 2010 and to ensure that all new qualifications issued from 2012 carry a reference to the appropriate EQF level. http://ec.europa.eu/education/lifelong-learning-policy/doc44_en.htm.

Condliffe Langemann (2000:xi) suggest that the science of education has been dominated by “…forces favoring a narrowly individualistic, behaviourally oriented and professionalized conception of educational study” and that the position of Thorndike “won” and that Dewey “lost”. This adds another perspective to the description of Ewell (2005).

ISI (Institute for Scientific Information®) Web of Science® provides researchers, administrators, faculty, and students with access to the world’s leading citation databases. Authoritative, multidisciplinary content covers over 10,000 of the highest impact journals worldwide, including Open Access journals and over 110,000 conference proceedings. http://isiknowledge.com.

ERIC—the Education Resources Information Center—is an online digital library of education research and information. ERIC is sponsored by the Institute of Education Sciences (IES) of the US Department of Education. ERIC provides ready access to education literature to support the use of educational research and information to improve practice in learning, teaching, educational decision-making, and research. (http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/resources/html/about/about_eric.html).

The journal Higher Education Management and Policy targets administrators and managers of institutions of higher education and researchers in the field of institutional management. It covers the field through articles and reports on research projects, and serves as a source of information on activities and events organised by OECD’s IMHE. www.puck.sourceoecd.org.

See the website of the Australian Government. http://www.dest.gov.au/sectors/school_education/policy_initiatives_reviews/national_goals_for_schooling_in_the_twenty_first_century.htm.

References

Adam, S. (2004) Using learning outcomes. A consideration of the nature, role, application and implications for European education of employing “learning outcomes” at the local, national and international levels. UK Bologna seminar 1–2 July, Heriott-Wyatt University, Edinburgh. Scotland.

Allan, J. (1996). Learning outcomes in higher education. In Studies in Higher Education, 21(1), 93–108.

Avis, J. (2000). Policing the subject: learning outcomes, managerialism and research in PCET. British Journal of Educational Studies, 48(1), 38–57.

Biesta, G. (2009). Good education in an age of measurement: on the need to reconnect with the question of purpose in education. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 21(1), 33–46.

Biggs, J. B., & Collis, K. F. (1982). Evaluating the quality of learning: The SOLO taxonomy. Australia: Academic.

Brady, L. (1996). Outcome-based education: a critique. The Curriculum Journal, 7(1), 5–16.

Brady, L. (1997). Assessing curriculum outcomes in Australian schools. Educational Review, 49(1), 57–65.

Burke, J. (1995). Outcomes, Learning and the curriculum. Implications for NVQs, GNVQs and other qualifications. London: The Falmer.

Buss, D. (2008). Secret destinations. In Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 45(3), 303–308.

Capper, C. A., & Jamison, M. T. (1993). Outcome-based education reexamined: from structural functionalism to poststructuralism. Educational Policy, 7(4), 427–446.

Cochran-Smith, M. (2001). The outcomes question in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17, 527–546.

Condliffe Langemann, E. (2000). An elusive science: The troubling history of educational research. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2004). Standards, Accountability, and school reform. Teachers College Record, 106(6), 1047–1085.

Davies, A. (2002). Writing learning outcomes and assessment criteria in art and design. Retrieved September 2008 from http://www.arts.ac.uk/docks/cltad_learningoutcomes.pdf.

Eisner, E. W. (1979). The education imagination. On the design and evaluation of school programs. Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc New York, Collier Macmillan Publishers London.

Eisner, E. W. (2005). Reimagining schools: The selected works of Elliot W. Eisner. Routledge: World Library of Educationalists Series.

Ewell, P. (2005). Applying learning outcomes to higher education: An overview. Paper prepared for the Hong Kong University Grants Committee. National Center for Higher Education Management Systems.

Furman, G. C. (1994). Outcomes-based education and accountability. Education and Urban Society, 26(4), 417–437.

Gagné, R. M. (1974). Learning for instruction. Illinois: The Dryden Press Hinsdale.

Gall, M. D., Borg, W. R., & Gall, J. P. (1996). Educational research an introduction. USA: Longman.

Harden, R. M. (2002). Learning outcomes and instructional objectives: is there a difference? Medical Teacher, 24(2), 151–155.

Harden, R. M., Crosby, J. R., & Davis, M. H. (1999). AMEE Guide No 14. Outcome-based education. Part 1—An introduction to outcome-based education. Medical Teacher, 21(1), 7–14.

Hargreaves, A., & Moore, S. (2000). Educational outcomes, modern and postmodern interpretations: response to Smyth and Dow. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 21(1), 27–42.

Hussey, S., & Smith, P. (2003). The uses of learning outcomes. Teaching in Higher Education, 8(3), 357–368.

Hussey, S., & Smith, P. (2008). Learning outcomes: a conceptual analysis. Teaching in Higher Education, 13(1), 107–115.

James, B., & Brown, S. (2005). Grasping the TLRP nettle: preliminary analysis and some enduring issues surrounding the improvement of learning outcomes. Curriculum Journal, 16(1), 7–30.

Jessup, G. (1991). Outcomes. NVQs and the emerging model of education and training. London: Routledge Falmer.

Kellaghan, T., & Greaney, V. (2001). Using assessment to improve the quality of education. Paris: UNESCO.

King, J. A., & Evans, K. M. (1991). Can we achieve outcome-based education? Educational Leadership, 49(2), 73–75.

MacBeath, J., & Moos, L. (2009). First editorial. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 21(1), 1–4.

Malan, STP (2000) The “new paradigm” of outcomes-based education in perspective. Journal of Family Ecology and Consumer Science, 28.

Melton, R. (1996). Learning outcomes for higher education: some key issues. British Journal of Educational Studies, 44(4), 409–425.

Moon, J. (2005). Linking Levels, Learning Outcomes and Assessment Criteria. Paper presented at the Bologna meeting in Bergen, Norway, in 2005. http://www.bolognabergen2005.no/EN/Bol_sem/Seminars/040701-02Edinburgh/040701-02Linking_Levels_plus_ass_crit-Moon.pdf retrieved autumn 2008.

Morcke, A. M. G., Wickmann-Hansen, D., Guldbrandsen, N., & Eika, B. (2006). Complex perspectives on learning objectives: stakeholders’ beliefs about core objectives based on focus group interviews. Medical Education, 40, 675–681.

Nusche, D. (2008). Assessment of learning outcomes in higher education: A comparative review of selected practices. OECD Education Working Paper No. 15. 29 February 2008, Directorate for Education.

Møller, J., Prøitz, T. S., & Aasen, P. (2009). Kunnskapsløftet—tung bør å bære? NIFU STEP report 42. Oslo.

Otter, S. (1992). Learning outcomes in higher education. A Development Project Report. UDACE, Department of Employment, London (England).

Rees, C. E. (2004). The problem with outcomes-based curricula in medical education:insights from educational theory. Medical Education, 38(6), 593–598.

Searle, J. R. (1995). The construction of social reality. New York: The Free.

Shepard, L. A. (2000). The role of assessment in a learning culture. Educational Researcher, 29(7), 4–14.

Smythe, J., & Dow, A. (1998). What’s wrong with outcomes? Spotter planes, action plans and steerage of the educational workplace. British Journal of Sociology of Education., 19(3), 291–302.

Spady, W. G., & Marshall, K. J. (1991). Beyond traditional outcome based education. Educational Leadership, 49(2), 67–72.

Spady, W. G. (1988). Organizing for results: the basis of authentic restructuring and reform. Educational Leadership, 46(2), 4–8.

Stensaker, B. (2003). Trance, transparency and transformation. The impact of external quality monitoring in higher education. Quality in Higher Education, 9, 151.

Stensaker, B., Brandt, E., & Solum, N. H. (2008). Changing systems of external examination. Quality Asurance in Education, 16(3), 211–223.

Telhaug, A. O., Mediås, A. O., & Aasen, P. (2006). The Nordic model in education: education as part of the political system in the last 50 years. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 50(3), 245–283.

Wagenaar, T. C. (2002). Outcomes assessment in sociology: prevalence and impact. Teaching Sociology, 30(4), 403.

Wilson, C. D., Miles, C. L., Baker, R. L., & Schoenberger, R. L. (2000). Learning outcomes for the 21st century: Report of a community college study. Laguna Hills: League for innovation in the community colleges.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Jorunn Møller, Nicoline Frølich and Bjørn Stensaker for their valuable comments on an earlier draft of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Prøitz, T.S. Learning outcomes: What are they? Who defines them? When and where are they defined?. Educ Asse Eval Acc 22, 119–137 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-010-9097-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-010-9097-8