Abstract

This study conducts an exploratory factor analysis on Wickman’s (2004) Pastors at Risk Inventory that measures the likelihood of whether clergy may face forced or unforced resignation. An online survey was administered to 285 evangelical pastors containing 42 Likert-type items developed from 20 years of qualitative practitioner ministry among clergy. The two factors identified—vision conflict and compassion fatigue—are discussed in relation to the extant literature and in their unique function with clergy. Results indicate that varying levels of disparity typically exist between expected ministry outcomes and actual ministry experiences, and that vision conflict and compassion fatigue are more likely among clergy who lack a support team and/or whose church has recently plateaued or declined in attendance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Clergy are leaving the ministry in greater numbers than ever before (Beebe 2007; Hoge and Wenger 2005; Lehr 2006; Palser 2005) as a significant and increasing cross-section of evangelical clergy express a growing sense of spiritual, physical, emotional, and social bombardment (London and Wiseman 2003; Wells 2002). According to the extant literature, contributors to clergy fall-out include such issues as interpersonal disagreements with parishioners, role overload, lack of personal and professional boundaries, loss of hope for positive change, and financial pressure (Beebe 2007; Wickman 2004). Unfortunately, these conditions present themselves as typical liabilities within pastoral ministry (Kisslinger 2007; London and Wiseman 2003).

This study uses an instrument developed by a pastoral practitioner that measures unique factors that contribute to clergy’s experience of being at risk of either forced or unforced resignation. By identifying these factors, the purposeful development of prevention and remediation strategies may arise to address the phenomena associated with pastors at risk.

Methods

Qualitative research

The genesis of the present quantitative research began with a qualitative study of pastors of the Evangelical Free Church of America by Chuck Wickman (1984) that examined the reasons for career change from church to secular work. Wickman’s initial investigation was extended through the use of the technique described by Silverman (2005) as immersion, where the practitioner’s field study allowed him to work closely among evangelical clergy who were at risk of being forced to resign from their places of ministry and/or reported symptoms resembling burnout that could result in unforced resignation (Kerlinger and Lee 2000; Maslach 2003; Maslach and Jackson 1981a, b; Schaufeli et al. 2008). According to Wickman (Anonymous 1997), some clergy leave the ministry “for ethical or moral reasons, but most just [have] conflicts at their churches” (p. 67).

The grounded theory approach employed by Wickman, based on established qualitative tradition (Creswell 1998, 2003), resulted in the collection of a wide breadth of data from clergy serving in numerous venues and circumstances over approximately a 20-year period and resulted in the gradual development of a quantitative instrument based on the interrelationship of the categories that emerged from the data (Patton 2002). According to Wickman (personal communication, July 23, 2008), the subjective nature of pastoral exits represents the integration of varying issues of causality involving the clergy member’s personality, personal history, physical location of the church along with its local culture, sensitivity to local culture norms, and acceptability of the pastor by the church. Wickman reported numerous phenomena that result in clergy at risk of forced or unforced resignation, including: physical, spiritual, emotional loss of energy; growing cynicism about personal value in the ministry; increasing apathy regarding ministry, feeling like they do not care; feeling more and more like a robot, doing what they must only by going through the motions of ministry; a rising sense of bother about ministry; an increased desire to procrastinate; perception that trust is turning to suspicion; tendency to withdraw from situations involving stressors; more distance between self and ministry, more impatience with congregation; loss of sense of humor; increased callousness toward people; feeling that life is increasingly stressful; feelings of helpless to change or break free from being overwhelmed; difficulty in saying “no”; and, desire to be “liked.”

Survey design

The development of a survey inclusive of the breadth of antecedents of forced or unforced clergy resignation was one of the outcomes of the years of working among clergy as a practitioner (Chuck Wickman, personal communication, July 23, 2008). The 42-item Likert-type survey assembled by Wickman (2004) represents the summative product of his previous qualitative work and, prior to the present research, has been used for over 4 years and among 500 clergy respondents. The Appendix shows the 42-item survey instrument, Pastor in Residence: At-Risk Pastor Profile (Wickman 2004), along with several demographic “yes/no” and “fill-in” questions.

The purpose of the present research is to extend the work initiated by Wickman (2004) by continuing the development of the 42-item instrument that identifies antecedents of clergy at risk of exiting the ministry. The primary research question is straightforward: “What are the factors of clergy at risk of forced or unforced resignation, if any, that are the result of correlations among the items in the survey developed by Wickman?” The second research question is dependent on the outcome of the first: “Do any of the dimensions identified by Wickman’s survey appear discriminant as issues that uniquely face clergy when compared with the extant literature?” The goal is to determine what factors may inform future research and remediation among clergy at risk of exiting the ministry.

Data collection

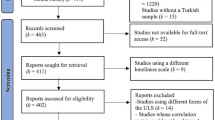

Participants for this study were evangelical clergy (N = 285) who responded to an online version of the Pastors at Risk Instrument (PaRI) over a three-week period in early 2008. Of these, 117 (41%) were clergy associated with The Foursquare Church, 69 (24%) from the Assemblies of God, 19 (7%) from various evangelical churches, and 80 (28%) who chose not to indicate their affiliation. In addition, this cross-section of clergy indicated that 34% were in their first church and that a majority (53%) were in their second or third church. Just over one fourth of the clergy (28%) were only 2 or 3 years into ministry at their present church. The survey indicated that 36% were between 35 and 49 years of age—these are the years Wickman (2004) found were most difficult for clergy. Only 28% served at a church that had forced a pastor to resign in the past. The majority of the sample (55%) served in churches where the attendance had plateaued or declined recently. 30% reported having no support team with which to meet regularly. 18% indicated that their church had constructed a new building within the past 2 years.

Results

Factor analysis

Factor analysis was conducted on the 42-item PaRI using SPSS 15 (2006). No reverse scoring was necessary. Table 1 shows the principle component matrix using Varimax rotation and Kaiser Normalization with a loading of .40 and above (Field 2005).

Reliability statistics were run with every individual factor so that each α could be assessed, and this resulted in the confirmation of two factors (Girden 2001). Although four factors were identified through the analysis, Cronbach’s α readings of >.70 occurred only in factor one (0.90) and factor two (0.85). Factor three (0.68) and factor four (0.55) are considered unreliable (Vogt 2005), although in further research factor three (0.68) could be reconsidered because “values of 0.60 to 0.70 [are] deemed the lower limit of acceptability” (Hair et al. 2006, p. 102), especially since the number of responses is high (Field 2005). A scree plot also supported a two-factor result (Kaiser 1960; Pallant 2006).

Thematic considerations

Table 2 focuses on the items that loaded on Factor 1 (α is 0.90). These correlated items reflect an inner confusion or conflict about what was expected in the ministry and resulted in dissatisfaction, futility, and disillusionment. The most highly correlated items involve negative responses with regard to concepts such as satisfaction, joy, purpose, calling, and resigning. Thus, we labeled Factor 1 as vision conflict. Vision conflict can entail a sense of personal failure based on unrealistic expectations about what comprises ministry effectiveness.

Table 3 focuses on the items that correlated as Factor 2 (α is 0.85). Together these items reflect an overwhelming physical and emotional stress, as though the person were falling short in spite of trying to minister as effectively as possible. The most highly correlated items are excessive ministry demands, feeling overworked, and feeling extreme stress. Thus, we labeled Factor 2 as compassion fatigue, similar to what will be mentioned later in the literature review in conjunction with general burnout research.

Pearson’s product–moment correlation

Composite variables were built using items from each of the two factors, vision conflict and compassion fatigue, so that additional analyses could be performed. A Pearson’s product–moment correlation (0.49; p < .01) showed a medium-strength correlation between vision conflict and compassion fatigue pairwise. This confirms that vision conflict and compassion fatigue correlate together—as one is higher or lower, the other one generally reflects the same higher or lower score.

T-tests

T-tests were run using the composite variables—vision conflict and compassion fatigue—with the yes/no questions at the end of the survey (items 43–50—see appendix). The results of the analysis showed significance only with questions 47, 48 and 49 (p < .05), which are detailed in Table 4.

T-test for Q47—church-forced resignation

An independent-samples t-test (Pallant 2006) was conducted to compare the vision conflict scores for clergy not serving in churches that have in the past forced a pastor to resign and clergy serving in churches that have in the past forced a pastor to resign. There was a significant difference in scores for clergy not serving in churches that have in the past forced a pastor to resign (M = 0.81, SD = 0.67) and clergy serving in churches that have in the past forced a pastor to resign (M = 1.01, SD = 0.77); [t(285) = −2.16, p = .03 < .05]. The magnitude of the differences in the means was fairly small: 2% (η squared = 0.02).

An independent-samples t-test was conducted to compare the compassion fatigue scores for clergy not serving in churches that have in the past forced a pastor to resign and clergy serving in churches that have in the past forced a pastor to resign. There was a significant difference in scores for clergy not serving in churches that have in the past forced a pastor to resign (M = 1.46, SD = 0.79) and clergy serving in churches that have in the past forced a pastor to resign (M = 1.68, SD = 0.77); [t(285) = −2.14, p = .03 < .05]. The magnitude of the differences in the means was fairly small: 2% (η squared = 0.02).

T-test for question 48—support team

An independent-samples t-test was conducted to compare the vision conflict scores for clergy with no support team they meet with regularly and clergy who have a support team with which they met regularly. There was a significant difference in scores for clergy with no support team with which they meet regularly (M = 0.74, SD = 0.65) and clergy with a support team with which they meet regularly (M = 1.17, SD = 0.74); [t(285) = −4.86, p = .00 < .05]. The magnitude of the differences in the means was moderate: 8% (η squared = 0.08).

An independent-samples t-test was conducted to compare the compassion fatigue scores for clergy with no support team they meet with regularly and clergy who have a support team with which they met regularly. There was a significant difference in scores for clergy with no support team with which they meet regularly (M = 1.38, SD = 0.76) and clergy with a support team with which they meet regularly (M = 1.86, SD = 0.74); [t(285) = −4.86, p = .00 < .05]. The magnitude of the differences in the means was moderate: 8% (η squared = 0.08).

T-test for Q49—attendance problems

An independent-samples t-test was conducted to compare the vision conflict scores for clergy not serving in churches that have plateaued or declined in attendance recently and clergy serving in churches that have plateaued or declined in attendance recently. There was a significant difference in scores for clergy not serving in churches that have plateaued or declined in attendance recently (M = 0.59, SD = 0.52) and clergy serving in churches that have plateaued or declined in attendance recently (M = 1.10, SD = 0.75); [t(285) = −6.71, p = .00 < .05]. The magnitude of the differences in the means was large: 14% (η squared = 0.14).

An independent-samples t-test was conducted to compare the compassion fatigue scores for clergy not serving in churches that have plateaued or declined in attendance recently and clergy serving in churches that have plateaued or declined in attendance recently. There was a significant difference in scores for clergy not serving in churches that have plateaued or declined in attendance recently (M = 1.35, SD = 0.82) and clergy serving in churches that have plateaued or declined in attendance recently (M = 1.66, SD = 0.73); [t(285) = −3.44, p = .00 < .05]. The magnitude of the differences in the means was small to moderate: 4% (η squared = 0.04).

Analyses of effects

Analyses of the effects of yes/no questions involving church-forced resignation (Q47), support team (Q48), and attendance problems (Q49) on each of the composite variables are displayed in Tables 5 and 6 respectively. As shown in Table 5, only support team and attendance problems have significant main effects on vision conflict. The main effect of church-forced resignation was not significant. Additionally, no interactions effects were found to be significant.

Table 6 indicates that, of the three independent variables, only support team has a significant main effect on compassion fatigue. The interaction effect of support team and attendance problems on compassion fatigue was also found significant. Church-forced resignation was not significant in any level of effect.

Discussion

This present study confirms at least two significant areas of concern for clergy in terms of sustaining a sense of positive ministry continuance. An individual look into each of these dimensions reveals a unique contribution in understanding the breadth of circumstances that converge in the roles engaged by those who serve in ministry.

Vision conflict

The term vision conflict does not exist as a named dimension in any of the literature associated with research involving clergy. However, numerous scholarly and popular press sources discuss clergy’s feelings of disparity between what they expected to happen by answering the call to ministry and the events that actually take place. From the outset of Wickman’s (1984) practitioner work that informed the development of PaRI, one of the frequent areas of discussion with clergy revolved around their sense of why they were called into the ministry and the discrepancy between the results clergy expect versus what actually occurs: “Once in the ministry there are problems and pastors can begin to question whether they were called” (C. Wickman, personal communication, July 23, 2008). The negative satisfaction, limited sense of joy, loss of meaning and calling—as depicted in items 6, 19, 26, and 28 (Table 2)—are indicators that ministry expectations have fallen short of actual experiences and that vision conflict exists.

The connection between a sense of unrealistic expectations in ministry and vision conflict are unquestioned. Lehr’s (2006) research examining clergy concluded that ministry lives tend to be constructed around great demands, high stress, unrealistic expectations, amid environments of conflict and are thus vulnerable to lapse into codependent practices that bring further endangerment. According to Clinton (1988), there is an inner expectation for ongoing ministry development in the life of clergy even though trials and frustration are natural experiences for clergy. Weber and Goetz (1996) support the notion that clergy may underestimate the difficulty associated with a ministerial role when they write, “the pastor who is most Christlike is not the one who is fulfilled in every moment of his ministry but the one whose ministry has in it unbelievable elements of crucifixion” (p. 30). Hoge and Wenger (2005) interviewed clergy who left the ministry and noted that ministers had a much different expectation about how their time would be allotted than what actually took place. Those who left the ministry “did not attribute the problem to specific conflicts within the congregation or with denominational officers; their complaints were more general, more colored by self-doubt, and more typical of individuals who are depressed” (Hoge and Wenger 2005, p. 115). The foregoing perspectives suggest that clergy may not adequately be prepared for what they will experience in the ministry and that what this research labels as vision conflict is a natural part of what the ministry holds (White 2007; Wickman 1984).

The degree of disparity in the ministry expectations on the part of both parishioners and clergy exemplifies another crucial example of vision conflict in the literature (Kisslinger 2007). Hands and Fehr (1994) observed of clergy that they were “people who had to live behind a professional façade which would impose considerable demands on their mental and emotional health” (p. xii). According to McIntosh and Rima (1997), the unrealistic expectation by clergy to achieve success becomes coupled with personal dysfunctional realities that are a carry-over from needs from an earlier time of life. The majority of tragically fallen Christian leaders feel “driven to achieve and succeed in an increasingly competitive and demanding church environment” (McIntosh and Rima 1997, p. 14).

The connection between the clergy’s sense of call and their motive for entering the ministry is also seen in the literature as informing an understanding of vision conflict (Jinkins 2002). A healthy view of motive begins with values and yields beliefs, which lead to intentions, which result in behaviors (Winston 2002). However, for some clergy, an examination of motives is either ignored or overshadowed by unrealistic expectations and false hopes. Willimon (1989) asserts that failure to properly evaluate the initial reasons for entering the ministry is a common tendency on the part of clergy. At the same time, Wood (2001) identifies motive as being a contributor to lower numbers of young people choosing pastoral ministry when he states, “why in the world would a talented young person commit to a life of low salary, low prestige, long hours, no weekends and little room for advancement” (p.19). For many clergy members, the necessity of bivocationality multiplies the cost of the decision to pursue their calling to the ministry (Bickers 2000, 2004).

Malony and Hunt (1991) emphasize the importance of differentiating between circumstance and personality—outside-the-person traits and individual motives. Such a differentiation allows for a clearer picture in defining the impact of individual traits such as a sense of calling that lie “somewhere between interest and feelings” (Malony and Hunt 1991, p. 19). The connection between motive and vision conflict can also be seen through the willingness or ability of the clergy to adjust to changing social conditions and work circumstances. Beebe (2007) posits that little attention is paid to the internal psychological dynamics surrounding social expectations of the clergy role, and that those circumstances have greatly changed in the last three decades. Snyder (1979) posits that some clergy have great difficulty in managing change but that the technological age portends inevitable and ongoing social change. Lack of appropriate motivation to navigate uncertain social change is related to increased vision conflict.

Compassion fatigue

The literature describes compassion fatigue more clearly than vision conflict since the term is already referenced numerous times using similar attributes as have been uncovered in this present research (Joinson 1992; Marchand 2007; Musick 1997; Pfifferling and Gilley 2000; Wells 2004). Compassion fatigue has also been an occasional topic for the popular press (Focus on the Family 2008; Johne 2006). The physical and emotional stresses that are outlined by the three items with the highest loadings as shown in Table 3—“I feel overworked,” “I feel my work is too demanding,” and “I feel my life is far too stressful”—are similar to the dimensions associated with the Maslach Burnout Inventory (Chandler 2006; Foss 2002; Maslach and Jackson 1981a, b, 1986; Maslach et al. 1996; Maslach and Leiter 2008). Understanding exhaustion, both physical and emotional, is a critical topic in the study of classical burnout (Maslach et al. 2001; Schaufeli et al. 2008). Pfifferling and Gilley (2000) add spiritual fatigue to the list of attributes describing compassion fatigue. Some researchers have used comparable terms such as emotional labor or compassion stress when referring to compassion fatigue (Boyle and Healy 2003; de Jonge et al. 2008; Figley 1992; Pienaar and Willemse 2008). However, tracing compassion fatigue among literature directed specifically to the clergy uncovers a unique extension of emphases that carries the definition of the term beyond the specifications of classical burnout due to the typical breadth of circumstances associated with normal ministry functions (Flannelly et al. 2005; Marchand 2007; Pfifferling and Gilley 2000).

One of the first to employ the term compassion fatigue in association with ministry settings was Hart (1984). He used the term compassion fatigue when counseling members of the clergy who were dealing with depression that resulted from the effects of ministry upon personal life. Numerous researchers and practitioners since have described the antidotes for ministry stress that parallel Wickman’s (2004) items associated with compassion fatigue (Grosch and Olsen 2000; Heinen 2007; Husted 1996; London and Wiseman 1993; Sanford 1992). Helping a parishioner deal with a spectrum of issues can deplete a minister of his or her own emotional reserves and contribute to their vulnerability toward a range of maladies (Hart 1984). Compounding a sense of depression among clergy is the realization that effective ministry to a congregant does not mean that the congregant’s circumstances will always improve. Hauerwas and Willimon (1990) describe compassion fatigue in the following way: “It strikes people who take on too heavy a load of other people’s burdens, leaving little time or energy for themselves. Victims become disillusioned and depressed, and often start to show cracks in their professional veneer” (p. 247).

Flannelly et al. (2005) give special emphasis to compassion fatigue while differentiating the use of the term from burnout in research associated with chaplains and clergy who ministered in the aftermath of the September 11th attacks in New York City. They noted the value of clinical pastoral education as a way to decrease compassion fatigue and burnout while increasing compassion satisfaction in responders and non-responders alike. Pector (2005) distinguishes compassion fatigue from burnout by positing that ministry caregivers who suffer from compassion fatigue continue to fully give of themselves to their work in spite of physical, mental, and spiritual depletion.

The occurrence of compassion fatigue among the clergy is inevitable, especially since many of the duties performed by ministers are either similar to various secular jobs where high stress is common or place the clergy member in a circumstance where extreme trauma is being experienced (Holaday et al. 2001; Taylor et al. 2006). Boyle and Healy (2003) contend that balancing responses between the sacred and the profane in a heavily emotion-laden organization can be difficult, citing the rush of excitement experienced by emergency personnel when a life is saved. Members of the clergy experience a similar set of extremes. Emotional highs and lows are exacerbated by stress, demand, and exhaustion that characterize compassion fatigue among clergy according to the physical and social proximity of the minister to the congregants where he or she serves. Although Marcuson (2004) does not employ the term compassion fatigue, a theme of balance undergirds her exhortation for clergy to find a functional equilibrium when trying to realize when enough help is truly enough. As White (2007) posits, “people who work in ministry are often working in the very communities they rely upon for social and spiritual support, and the dual relationships that result can pose complications for their work and personal lives” (p. 7). Brown (2007) illustrates the high-low liability associated with the minister’s dedication to serve among people who may accuse or slander their minister if their needs are not addressed to their satisfaction. Indeed, compassion fatigue introduces an important dimension of understanding how people and relationships affect the physical, emotional, and spiritual health of the clergy.

Conclusion

The initial work associated with developing the PaRI yielded two factors—vision conflict and compassion fatigue—as discriminant dimensions that uniquely affect the likelihood that clergy may exit the ministry. The extant literature also provides scholarly support for the definition of vision conflict and compassion fatigue along with the attributes that accompany them. Identifying the circumstances associated with the prediction of the exiting of clergy from the ministry—for either forced or unforced reasons—moves the church to a place of reckoning the antecedents that contribute to likelihood of clergy continuance in the ministry.

Focusing on the issues related to vision conflict and compassion fatigue among clergy can cultivate an interest in pursuing remediation for those affected as well as increase better methods of understanding and promoting prevention of forced and unforced exits from the ministry. As we discovered in this present research, whether clergy have a support team and/or serve in a congregation where the attendance is declining are significant main effects respectively upon vision conflict that result in greater likelihood for clergy to exit the ministry (Table 5). The same two effects also contribute to clergy exits in terms of compassion fatigue (Table 6). However, with compassion fatigue the lack of a support team is the only main effect. Attendance problems are seen here as amplifying that effect through an interaction with the lack of team support. Future research may pursue these topics in order to develop a plan to increase remediation effectiveness. Another extension of this research could involve qualitative interviews with pastors, revising the PaRI if necessary, investigating other factors suggested by this research, and/or conducting additional studies with various groups of clergy, including a confirmatory factor analysis.

References

Anonymous. (1997). Ministry retrains ‘exited’ pastors. Christianity Today, 41(7), 67.

Beebe, R. S. (2007). Predicting burnout, conflict management style, and turnover among clergy. Journal of Career Assessment, 15(2), 257–275.

Bickers, D. (2000). The tentmaking pastor: The joy of bivocational ministry. Grand Rapids: Baker.

Bickers, D. (2004). The bivocational pastor. Kansas City: Beacon.

Boyle, M. V., & Healy, J. (2003). Balancing mysterium and onus: Doing spiritual work within an emotion-laden organizational context. Organization, 10(2), 351–373.

Brown, D. A. (2007). Cries against the shepherds: Filtering accusations against spiritual leaders. Aptos: Commended to the Word.

Chandler, D. J. (2006). An exploratory study of the effects of spiritual renewal, rest-taking, and personal support system practices on pastoral burnout (Ph.D. dissertation, Regent University, School of Leadership Studies, 2005). Retrieved April 16, 2008, from Dissertations & Theses @ Regent University database. (AAT 3194236).

Clinton, J. R. (1988). The making of a leader: Recognizing the lessons and stages of leadership development. Colorado Springs: Navpress.

Creswell, J. W. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Creswell, J. W. (2003). Research design: Qualitative, qnantitative, and mixed methods approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

de Jonge, J., Le Blanc, P. M., Peeters, M. C. W., & Noordam, H. (2008). Emotional job demands and the role of matching job resources: A cross-sectional survey study among health care workers. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 45(10), 1460–1469.

Field, A. (2005). Discovering statistics using SPSS (2nd ed.). London: Sage.

Figley, C. R. (1992, January). Compassion stress: Toward its measurement and management. Family Therapy News.

Flannelly, K. J., Roberts, S. B., & Weaver, A. J. (2005). Correlates of compassion fatigue and burnout in chaplains and other clergy who responded to the September 11th attacks in New York City. Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling, 59(3), 213–224.

Focus on the Family. (2008). How do I know if I am burned out or just tired? Retrieved May 5, 2008, from http://www.parsonage.org/faq/A000000544.cfm.

Foss, R. W. (2002). Burnout among clergy and helping professionals: Situational and personality correlates (Ph.D. dissertation, Fuller Theological Seminary, School of Psychology, 2001). Retrieved July 11, 2008, from Dissertations & Theses (PQDT) database. (AAT 3046366).

Girden, E. R. (2001). Evaluating research articles from start to finish (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Grosch, W. N., & Olsen, D. C. (2000). Clergy burnout: An integrative approach. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56(5), 619–632.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2006). Multivariate data analysis (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River: Pearson-Prentice Hall.

Hands, D. R., & Fehr, W. L. (1994). Spiritual wholeness for clergy: A new psychology of intimacy with God, self and others. Herndon: Alban Institute.

Hart, A. (1984). Coping with depression in the ministry and other helping professions. Waco: Word Books Publisher.

Hauerwas, S., & Willimon, W. (1990). The limits of care: Burnout as an ecclesial issue. Word & World, 10(3), 247–253.

Heinen, R. (2007, November 10). Some rest for the not-so-wicked: Pastors facing stress, burnout, take time for healing retreats. Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Retrieved July 14, 2008, from http://0-web.ebscohost.com.library.regent.edu/ehost/detail?vid=4&hid=17&sid=05d5c171-aa1f-4ec1-bac5-8161d128fcc7%40sessionmgr7.

Hoge, D. R., & Wenger, J. E. (2005). Pastors in transition: Why clergy leave local church ministry. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans.

Holaday, M., Lackey, T., Boucher, M., & Glidewell, R. (2001). Secondary stress, burnout, and the clergy. American Journal of Pastoral Counseling, 4(1), 53–72.

Husted, H. A. (1996). Four ways I’ve found encouragement. Leadership: A Practical Journal for Church Leaders, 17(3), 43–45.

Jinkins, M. (2002). Great expectations, sobering realities: Reflections on the study of clergy burnout. Congregations (Publication of the Alban Institute), 28(3), 11–13, 24–25.

Johne, M. (2006). Compassion fatigue: A hazard of caring too much. Medical Post, 42(3), 19.

Joinson, C. (1992). Coping with compassion fatigue. Nursing, 22(4), 16–122.

Kaiser, H. F. (1960). The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20, 141–151.

Kerlinger, F. N., & Lee, H. B. (2000). Foundations of behavioral research (4th ed.). Fort Worth: Harcourt College.

Kisslinger, S. A. (2007). Burnout in Presbyterian clergy of southwestern Pennsylvania (Doctoral dissertation, Indiana University of Pennsylvania, School of Graduate Studies and Research, 2007). Retrieved April 29, 2008, from Dissertations & Theses (PQDT) database. (AAT 3252060).

Lehr, F. (2006). Clergy burnout: Recovering from the 70-hour work week…and other self-defeating practices. Minneapolis: Fortress Press.

London, H. B., & Wiseman, N. B. (1993). Pastors at risk. Wheaton: Victor Books.

London, H. B., & Wiseman, N. B. (2003). Pastors at greater risk. Ventura: Regal.

Malony, H. N., & Hunt, R. A. (1991). The psychology of clergy. New York: Morehouse.

Marchand, C. T. (2007). An investigation of the influence of compassion fatigue due to secondary traumatic stress on the Canadian youth worker. (D.Min. dissertation, Providence Theological Seminary, 2007). Retrieved October 27, 2008, from Proquest Digital Dissertations. (AAT NR37197).

Marcuson, M. J. (2004). Helping or Overfunctioning? The Clergy Journal, 80(8), 11–13.

Maslach, C. (2003). Job burnout: New directions in research and intervention. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(5), 189–192.

Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981a). Maslach burnout inventory (Research ed.). Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981b). The measurement of experienced bumout. Journal of Occupational Behavior, 2(2), 99–113.

Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1986). The Maslach burnout inventory (2nd ed.). Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2008). Early predictors of job burnout and engagement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(3), 498–512.

Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., & Leiter, M. P. (1996). Maslach burnout inventory manual (3rd ed.). Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 397–422.

McIntosh, G. L., & Rima, S. D. (1997). Overcoming the dark side of leadership: The paradox of personal dysfunction. Grand Rapids: Baker.

Musick, J. L. (1997). How close are you to burnout? Family Practice Management. Retrieved November 24, 2003, from http://www.aafp.org/fpm/970400fm/lead.html

Pallant, J. (2006). SPSS survival manual (2nd ed.). Berkshire: Open University Press.

Palser, S. J. (2005). The relationship between occupational burnout and emotional intelligence among clergy or professional ministry workers (Ph.D. dissertation, Regent University, School of Leadership Studies, 2004). Retrieved April 16, 2008, from Dissertations & Theses @ Regent University database. (AAT 3162679).

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research & evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Pector, E. A. (2005). Professional burnout: Detection, prevention, and coping. The Clergy Journal, 81(9), 19–20.

Pienaar, J., & Willemse, S. A. (2008). Burnout, engagement, coping and general health of service employees in the hospitality industry. Tourism Management, 29(6), 1053–1063.

Pfifferling, J-H., & Gilley, K. (2000, April). Overcoming compassion fatigue. Family Practice Management, 7(4), 39–44, 65–66.

Sanford, J. A. (1992). Ministry burnout. Louisville: Westminster/John Knox Press.

Schaufeli, W. B., Taris, T. W., & van Rhenen, W. (2008). Workaholism, burnout, and work engagement: Three of a kind or three different kinds of employee well-being? Applied Psychology, 57(2), 173–203.

Silverman, D. (2005). Doing qualitative research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Snyder, H. (1979). The problem of wineskins: The church in a technological age. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press.

SPSS 15. (2006). Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 15.0 for Windows evaluation version. Chicago: SPSS.

Taylor, B. E., Weaver, A. J., Flannelly, K. J., & Zucker, D. J. (2006). Compassion fatigue and burnout among rabbis working as chaplains. Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling, 60(1–2), 35–42.

Vogt, W. P. (2005). Dictionary of statistics & methodology (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Weber, S., & Goetz, D. (1996). Tour of duty. Leadership: A Practical Journal for Church Leaders, 17(2), 22–30.

Wells, B. (2002). Which way to clergy health? Pulpit & Pew: Research on Pastoral Leadership. Retrieved July 15, 2008, from http://www.pulpitandpew.duke.edu/clergyhealth.html

Wells, B. S. (2004). Burnout and compassion fatigue in school counselors: A mixed method design (E.D. dissertation, Argosy University/Sarasota, School of Education, 2004). Retrieved July 15, 2008, from Dissertations & Theses (PQDT) database. (AAT 3302891).

White, J. D. (2007). Burnout busters: Stress management for ministry. Huntington: Our Sunday Visitor Publishing.

Wickman, C. A. (1984). An examination of the reasons for career change from church to secular work among pastors of the Evangelical Free Church of America. (D.Min. dissertation, Trinity Evangelical Divinity School). Retrieved July 24, 2008, from Dissertations & Theses: Full Text database. (AAT 0370080).

Wickman, C. A. (2004). Pastor in residence: At-risk pastor profile. Retrieved February 14, 2008, from Regent University, School of Global Leadership and Entrepreneurship website: http://www.regent.edu/acad/global/pir/pir_section1.cfm

Willimon, W. (1989). Clergy and laity burnout. Nashville: Abingdon.

Winston, B. E. (2002). Be a leader for God’s sake. Virginia Beach: Regent University.

Wood, D. J. (2001). Where are the younger clergy? The Christian Century, 118(12), 18–19.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Pastor in Residence: At-Risk Pastor Profile (Wickman 2004)

Section I

-

1.

I experience conflict with my Board as to the vision of the church

-

2.

I am confused about my major role in the church

-

3.

I feel isolated and alone

-

4.

My ability to trust church leadership is weak

-

5.

My relationship with staff is unhealthy

-

6.

I have lost the sense of meaning in my work

-

7.

My spouse and family are unhappy

-

8.

Music and worship style are big conflict issues in my church

-

9.

Church finances are inadequate

-

10.

My personal finances are suffering

-

11.

I feel I don’t have enough close friends with whom I can talk about my needs

-

12.

I feel overworked

-

13.

I feel my work is futile

-

14.

I feel my sense of confidence has diminished

-

15.

I feel I must prove myself a hard worker

-

16.

I wonder whether or not I am working in the area of my giftedness

-

17.

I feel that the church’s expectations of me are unclear

-

18.

I feel that there are more expectations on me than I can fulfill

-

19.

I wonder about my calling as a pastor

-

20.

I have diminished energy for my work

-

21.

I feel emotionally empty

-

22.

I feel my work is too demanding

-

23.

I feel my life is far too stressful

-

24.

I really don’t care much about what happens to my parishioners

-

25.

I feel I am not as sensitive as I once was

-

26.

Ministry doesn’t bring me satisfaction

-

27.

Generally, I feel exhausted

-

28.

I find little joy in my work

-

29.

I feel afraid that I will be forced out of the church I now serve

-

30.

I feel I would like to leave the church I now serve

-

31.

I feel I can’t meet all the needs of my people

-

32.

I seriously consider leaving the ministry entirely

-

33.

I feel my hope for success has not developed

-

34.

I don’t feel that my denominational leaders would be helpful, should I go to them with my problems

-

35.

My leadership and I have different theological positions

-

36.

I am having personality conflicts with people not on the board

-

37.

I feel my spouse would not really support me should I leave ministry

-

38.

Charges of moral failure are being made against me

-

39.

I feel insecure in my present position

-

40.

It is very difficult for me to say “no”

-

41.

I feel my personal relationship with Christ is a real problem

-

42.

Weeks go by without a scheduled “date” with my spouse

Section II

-

43.

I am in my first church

-

44.

I am now serving my second or third church

-

45.

I have been serving this church for just 2 or 3 years

-

46.

I am between 35 and 49 years of age

-

47.

The church I serve has in the past forced a pastor to resign

-

48.

I have no support team with which I meet regularly

-

49.

The church I serve has plateaued or declined in attendance recently

-

50.

We have built a new building in the past 2 years

Optional data should you wish to provide it:

-

51.

Your name:

-

52.

Phone:

-

53.

Denominational Affiliation

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Spencer, J.L., Winston, B.E. & Bocarnea, M.C. Predicting the Level of Pastors’ Risk of Termination/Exit from the Church. Pastoral Psychol 61, 85–98 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-011-0410-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-011-0410-3