Abstract

This paper compares the performance of Okun’s Law in advanced and developing economies. On average, the Okun coefficient—which measures the short-run responsiveness of labor markets to output fluctuations—is about half as large in developing as in advanced countries. However, there is considerably heterogeneity across countries, with Okun’s Law fitting quite well for a number of developing countries. We have limited success in explaining the reasons for this heterogeneity. The mean unemployment rate and the share of services in GDP are associated with the Okun coefficient, whereas other factors such as indices of overall labor and product market flexibility do not appear to play a consistent role.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The short-run relationship between output and labor market outcomes, documented by Okun (1962) for the United States, has since become famous as “Okun’s Law”. Ball, Leigh and Loungani, henceforth referred to as BLL (2017), show that Okun’s Law has held up well for a set of 20 advanced economies. The responsiveness of unemployment or employment to output—the so-called Okun coefficient—does vary across countries, however, and for reasons that are not easy to explain.

This paper extends that work to a larger group of countries that includes several developing economies. The motivation is two-fold. First, these countries account for a large, and growing, share of the global labor force. Hence, understanding the determinants of labor market outcomes in these countries is important. There is ample evidence that job creation contributes to individual and social welfare, whereas unemployment and job loss are associated with persistent loss of income, health problems, and breakdown of family and social cohesion (see the World Bank’s World Development Report on “Jobs” (2013) and Dao and Loungani (2010)).

A second motivation is to probe the common perception that labor market outcomes in developing countries reflect mostly structural factors rather than short-run cyclical fluctuations. Whether this perception is correct has important policy implications. If cyclical fluctuations account for a substantial part of labor market developments, macroeconomic stabilization policies—such as central bank actions, countercyclical fiscal policies and prudential policies to mitigate financial crises—gain in importance relative to structural policies (e.g. improving education and skills of the labor force).

The bulk of the literature on Okun’s Law has been for advanced economies; the studies for developing economies have been for particular countries or sometimes for regions. To our knowledge, this paper provides the first comprehensive look at Okun’s Law for a large set of countries over a fairly long period of time. We use 71 countries in our analysis, classified into 29 advanced and 42 developing countries. We use the IMF’s World Economic Outlook classification to decide which countries are considered ‘advanced’; the others are labeled developing. We restrict our sample to countries with at least 20 years of annual data and with a population exceeding 3 million. The time period is 1980 to 2015 but data for many developing countries starts later, as indicated in Table 10 in the Appendix.

Our three principal conclusions—based on estimating the short-run (annual) relationship between unemployment (or employment) and output—are as follows:

- 1)

On average, labor markets are less responsive to output fluctuations in developing countries than in advanced. For instance, the responsiveness of unemployment to output is −0.2 in developing countries compared with −0.4 for advanced economies. The fit of Okun’s Law is also poorer in developing countries than in advanced: the average R-square value is in the 0.2–0.3 range, again about half that in advanced countries.

- 2)

However, as found by BLL (2017) for advanced economies, there is considerable heterogeneity across developing countries in the Okun coefficient and the fit of Okun’s Law for developing countries. Hence there are a number of developing countries where short-run cyclical fluctuations appear to play an important role in labor market developments.

- 3)

We have limited success in explaining the heterogeneity in Okun coefficients. As in BLL (2016), we find an association between the Okun coefficient and the mean unemployment rate. The other variable that plays a role is the share of services in GDP, consistent with suggestions from the literature, e.g. Kapsos (2006).

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews Okun’s Law, Section 3 presents the main results and Section 4 delves into the determinants of cross-country differences in Okun coefficients. Section 5 provides our tentative conclusions.

2 Okun’s Law

Okun’s Law is an inverse relationship between cyclical fluctuations in output and the unemployment rate. Shocks to the economy cause output to fluctuate around potential and lead firms to hire and fire workers, changing the unemployment rate in the opposite direction. This relation can be expressed as:

where \( {u}_t^{\ast } \)and \( {y}_t^{\ast } \) are the trend components of the unemployment rate and log output, respectively. The error term of Eq. (1) captures factors that shift the cyclical unemployment-output relationship, such as unusual changes in productivity or in labor force participation.

The coefficient β in Eq. (1) in turn depends on how much firms adjust employment when output changes and on the cyclical response of the labor force:

where \( {l}_t^{\ast } \) and \( {e}_t^{\ast } \) are the trend values of the log of labor force and employment, respectively. The smaller is the cyclical response of the labor force, the stronger is the inverse correlation between β and βe.

The data on the unemployment rate, employment, labor force and real GDP come from the IMF’s World Economic Outlook database and are described in the Appendix. To measure the trend values of the unemployment rate, output, employment and the labor force, we use the Hodrick-Prescott (HP) filter. The smoothness parameter (λ) in the HP filter is set equal to 100 in our baseline results, but we check for sensitivity to an alternate value of λ = 12.Footnote 1

Another version of Okun’s Law posits a relationship between the changes in the unemployment rate and the growth rate of output:

The corresponding equations for employment growth and labor force growth are given as:

In this paper we do not tackle the issue of whether the gap version or the changes version should be the preferred specification of Okun’s Law. Often the changes version is used by authors because it does not require an explicit measurement of the trend components. But this is not a real solution because implicit assumptions about the trend components end up being subsumed in the constant term of Eq. (4) and in the error terms. We present evidence on both versions of Okun’s Law and leave resolution of which one is more appropriate to future research.

3 Main Results

3.1 Summary Statistics

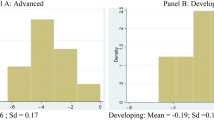

The top panel of Fig. 1 shows the histogram for the estimated β coefficients for the two groups. The average value of the coefficient is −0.4 for advanced countries and − 0.2 for developing countries. For both groups there is considerable heterogeneity; the standard deviation is 0.18 and 0.14 for advanced and developing countries, respectively. The bottom panel provides evidence on the fit of Okun’s Law as measured by the R-square statistic of the unemployment gap regressions. The average value in advanced countries is twice that in developing (0.6 compared with 0.3), but again with a lot of heterogeneity within each group.

This pattern of results broadly continues in Fig. 2, which shows the histograms of the βe estimates and the R-square values of the employment gap regressions. The mean value in advanced countries is a bit more than twice that in developing (0.6 vs. 0.25); the mean R-square value is also more than twice the value (0.5 vs. 0.2); and there is substantial variation within each country group as shown in the histograms and the reported standard deviations.

The distribution of βl estimates is different in the two groups, as shown in the top panel of Fig. 3. In advanced countries, the coefficient is positive in all but two cases; in contrast, in developing countries, the distribution is centered on zero, with nearly as many positive βl estimates as negative ones. The fit of these equations is quite low for both groups, as shown in the bottom panel of Fig. 3: the average R-square values are about 0.2 and 0.1 for advanced and developing countries, respectively.

To summarize, as a broad characterization, Okun’s Law holds about half as well in developing countries as in advanced: the average β coefficient and average R-square value are both about half that in advanced countries. The weaker unemployment response to cyclical fluctuations in developing countries is partly because of a smaller employment response (βe is smaller on average); in some cases the countercyclical response of the labor force (negative value of βl) adds to the weaker unemployment response.

Using the changes version of Okun’s Law does not lead to a major change in this assessment. The histograms of the estimates of γ, γe and γl are shown in Figs. 4, 5 and 6, respectively. The mean values of the γ and γe coefficients are again much higher for advanced than for developing countries, though not quite twice as high as was the case with the gap version (see Figs. 4 and 5, top panels). The fit of the employment equation is not as good in the changes version as in the gap version (Fig. 5, bottom panel). The distribution of γl and the fit of the labor force equation is quite similar in the changes and gap versions (Fig. 6).

While useful, a focus only on the averages misses the substantial heterogeneity illustrated in the histograms. Understanding some of the sources of this heterogeneity requires a closer look at the country-by-country estimates. We turn to this in the next sub-section and in Section 4.

3.2 Estimates by Country

The country estimates that underlie Figures 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5, and 66 are given in Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6. The main points from these tables are the following:

For advanced economies, with only one exception (Singapore), the estimates of β are all negative and significantly different from zero; for developing economies, the Okun coefficient is negative and significant in 36 out of 42 cases (Table 1). Okun’s Law appears to hold well in Poland and Colombia, with Okun coefficients of about −0.7 and − 0.4, respectively, and R-square values that exceed 0.4. For South Africa, the coefficient is −0.33, but the R-square value is low (0.16). For Russia, Okun’s law fits well but with a small coefficient, about −0.15.

For advanced economies, the coefficient estimate of βe is positive and significant in all cases; for developing economies, the coefficient is positive in 30 out of 38 cases and significant in 23 of them (Table 2). The largest coefficients are for South Africa and Egypt (both exceeding 0.8), though the R-square is low in the former case and high in the latter. Poland, Hungary and Chile are other countries with high coefficients and reasonably good fit.

Table 3 presents estimates of the cyclical response of the labor force. In advanced countries, the coefficient estimates are positive in all but two cases, and significantly so in 20 cases. For developing countries, the coefficients are positive in about half the cases, though often not significant. For both groups the R-square coefficients are fairly low.

Tables 4, 5 and 6 provide the estimates of γ, γe and γl. These do not substantively alter the main points given above. One difference, as already noted, is that the changes version of the employment equation does not fare as well as the gap version: fewer estimates of γe are significant and the fit of the equation is worse.

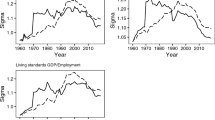

Table 7 classifies countries into a 3 × 3 matrix based on the absolute values of β and the R-square statistic. In 18 countries, Okun’s Law does poorly on both dimensions. In the other cells, the performance improves along at least of the dimensions. Figure 7 illustrates four cases—Colombia, Egypt, Poland and Russia—where Okun’s Law appears to hold well.

4 Determinants of Okun Coefficients

In this section we look into some of the factors that are associated with the cross-country variation in β and βe. The seven factors we consider are those suggested by previous studies. We first present a set of scatter plots to show the bivariate relationship between β and each of the seven factors (Figs. 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, and 14). In each figure, we show the slope of the estimated relationship for the full sample as well as separately for the advanced and developing country groups.

Mean unemployment rate: BLL (2017) document a positive relationship for advanced countries between the estimated Okun’s coefficient and the average level of unemployment: in countries where unemployment is higher on average, it also fluctuates more in response to output movements. While the reason for this association is not apparent, we find that a similar correlation holds for developing economies as well (Fig. 8).

Per capita GDP: The histograms showed a difference between the average values of the Okun coefficients between advanced and developing countries. Since the segmentation of the countries in the two groups was based on income, per capita GDP is an obvious candidate to explain some of the cross-country heterogeneity. As shown in Fig. 9, for both the overall sample and for the developing countries group, there is a negative relationship between per capita GDP and the Okun coefficient: in countries with higher per capita GDP, unemployment is more responsive to output fluctuations. However, the relationship does not hold for countries in the advanced country group.

Size of the shadow or informal sector: Agénor and Montiel (2008) and Mohommad et al. (2012) discuss the importance of the shadow or informal economy in developing economies; the existence of this sector can obscure relationships between the formal labor market and measured output, thus lowering the measured Okun coefficient. This view finds some confirmation in the data: Fig. 10 shows that for the full sample of countries, labor market and output fluctuations are less correlated in countries with larger shadow economies.

Share of services in GDP: Kapsos (2006) and Furceri et al. (2012) document that in countries where the service share is higher, employment tends to be more responsive in changes in output. We find a similar association for the full sample and for developing countries (Fig. 11).

Skill mismatch: Estevão and Tsounta (2011) suggest that skill mismatches can play a role in influencing how unemployment responds to shocks and present evidence supporting this from U.S. states. They measure skill mismatch as the difference between the skills embodied in the employment structure of a state (“demand”) and the skills reflected in the educational attainment of the state’s labor force (“supply”). Melina (2016) constructs similar measures of skill mismatch for many of the countries in our sample. We find that, for developing countries in particular, higher skill mismatch is associated with a weaker response of unemployment to output (Fig. 12).

Labor market and business regulations: Many observers suggest that the responsiveness of labor markets could depend on regulations governing labor and product markets. For instance, in discussing hiring and firing regulations in Middle Eastern and North African countries, Ahmed et al. (2012) argue that such regulations can discourage “firms from expanding employment in response to favorable changes in the economic climate.” That is, greater employment protection can dampen hiring and firing as output fluctuates, reducing the employment responsiveness. We find little association between the Okun coefficient and aggregate measures of either labor market flexibility (Fig. 13) or product market flexibility (Fig. 14). Looking at individual components of these aggregate measures could yield stronger results; we plan to investigate this in future work.

Table 8 shows correlations among the explanatory variables and Table 9 reports regression results. When all variables are entered in the regression together, only the effects of average unemployment and the share of services are statistically significant, as shown in the first column of the regression. Dropping the mean unemployment rate—on the grounds that it is not truly a causal factor—does not change things much (second column). The third includes only the average unemployment and the share of services; this regression has an adjusted R-square of 0.5, not much lower than the one in the first column. The three other column of the Table repeat the exercise for βe, reaching broadly similar results, though in this case the difference in R-square values between the regression with all variables and the one with only two variables is more pronounced (0.48 vs. 0.33).

5 Conclusions

The structural challenges facing labor markets in developing economies deservedly get a lot of attention. In many of these economies, unemployment rates, and particularly youth unemployment rates, are alarmingly high. Others face the challenge of raising labor force participation, particularly among women. The results of this paper lend support to a focus on policies to address these structural challenges relative to the cyclical considerations that are more dominant in advanced economies. We find that the cyclical relationship between jobs and growth is considerably weaker, on average, in developing than in advanced economies. At the same time, the finding of a significant Okun’s Law relationship in many developing countries suggests that cyclical considerations should not be ignored. Aggregate demand policies that support output growth in the short term are also needed to keep many of these economies operating closer to full employment.

Notes

To address the well-known end-point problem with the HP filter we extend all series to 2021 using the IMF’s World Economic Outlook projections and then run the HP filter on the extended series to derive the trend estimate for 2015.

Low-skilled sectors are (i) mining and logging and (ii) construction; semi-skilled sectors are (i) manufacturing, (ii) trade, transportation and utilities, (iii) leisure and hospitality, (iv) other services; high-skilled sectors are (i) information, (ii) financial activities, (iii) education and health care, (iv) professional and business services, and (v) government.

References

Agénor PR, Montiel PJ (2008) Development macroeconomics. Princeton University Press, Princeton and Oxford

Ahmed, M., Guillaume, D., & Furceri, D. (2012). Youth unemployment in the MENA region: determinants and chall sing the 100 Million Youth Challenge -- Perspectives on Youth Unemployment in the Arab World, 8–11.

Ball L, Leigh D, Loungani P (2017) Okun’s law: fits at 50? J Money Credit Bank 49(7):1413–1441

Furceri, D., Crivelli, E., & Toujas-Bernate, J. (2012). Can policy affect employment intensity of growth? A cross-country analysis, IMF Working Paper No. 12/218

Dao M, Loungani P (2010) The human cost of recessions: assessing it, reducing it (No. 2010–2017). International Monetary Fund, Washington DC

Estevão MM, Tsounta E (2011) Has the great recession raised US structural unemployment? IMF Working Papers:1–46

Hassan M, Schneider F (2016) Size and Development of the Shadow Economies of 157 Countries Worldwide, IZA Discussion Paper No. 10281

Kapsos S (2006) The employment intensity of growth: trends and macroeconomic determinants. In: Labor Markets in Asia. Palgrave Macmillan, UK, pp 143–201

Melina G (2016) Enhancing the Responsiveness of Employment to Growth in Namibia, IMF Selected Issues Paper, November (Washington, DC)

Mohommad MA, Singh MA, Jain-Chandra S (2012) Inclusive growth, institutions, and the underground economy. International Monetary Fund, Washington DC, pp 12–47

Okun AM (1962) Potential GNP: its measurement and significance. In: Proceedings, business and economic statistics section of the American Statistical Association, pp 89–104

World Bank (2013) World Development Report: Jobs

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Nathalie Gonzalez Prieto, Zidong An, Ezgi Ozturk and Jair Rodriguez for excellent research assistance. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Data Appendix

1.1.1 Output

GDP data comes from the July 2016 version of the WEO. It corresponds to real GDP in national currency.

\( {\boldsymbol{y}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}-{\mathbf{y}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}^{\ast} \): cycle after filtering the logarithm of the GDP multiplied by 100, with a Hodrick-Prescott filter with lambda 100.

Δyt: Percentage change in GDP = 100* ln (\( \frac{y_t}{{\mathrm{y}}_{\mathrm{t}-1}}\Big) \)

1.1.2 Labor market statistics

Labor market data comes from the WEO. This data is internally reported by the desk economist and follows the standard ILO when available. In other cases, it can follow the national definition.

\( {\boldsymbol{e}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}-{\boldsymbol{e}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}^{\ast} \): cycle after filtering the logarithm of the employment multiplied by 100, with a Hodrick-Prescott filter with lambda of 100.

\( {\boldsymbol{u}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}-{\boldsymbol{u}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}^{\ast} \) cycle after filtering the unemployment rate with a Hodrick-Prescott filter, with lambda of 100

\( \boldsymbol{l}{\boldsymbol{f}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}-\boldsymbol{l}{\boldsymbol{f}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}^{\ast} \) cycle after filtering the logarithm of the labor force multiplied by 100, with a Hodrick-Prescott filter with lambda of 100

1.1.3 Determinants of the Okun Coefficient

Average Unemployment

Average unemployment rate from the WEO for the period covered in each regression. The number of periods used to compute the average can vary depending on the country. This indicator comes from national sources that use household surveys and follow the ILO definition of unemployment: unemployed comprise all persons above a specified age who during the reference period were:

Without work, that is, were not in paid employment or self-employment during the reference period;

Currently available for work, that is, were available for paid employment or self-employment during the reference period; and

Seeking work, that is, had taken specific steps in a specified recent period to seek paid employment or self-employment.

This means that the unemployment rate does not include the informal workers as unemployed.

GDP per capita: is gross domestic product divided by midyear population. GDP is the sum of gross value added by all resident producers in the economy plus any product taxes and minus any subsidies not included in the value of the products. It is calculated without making deductions for depreciation of fabricated assets or for depletion and degradation of natural resources. Data are in constant 2010 U.S. dollars. Average of the period used in the regression to estimate the coefficients (β′s & γ ′ s) the number of periods used to compute the average can vary depending on the country.

Shadow Economy

Average shadow economy prevalence between 1999 and 2007. Taken from Hassan and Schneider (2016) they use indicators such as the use of cash, the growth of the economy and of the labor force, the tax burden the size of the government and other proxies to quantify the scope of the shadow economy in a country and build a dataset comparable across countries.

Skill Mismatch Index

Calculate by IMF Staff. It takes the ILO estimations of shares of the employment by sector and shares of the population by education level. Given a set of skills, the index is a measure of the distance between the percent of the labor force with a given level of skills (skill level supply) and the proportion of employees with the same level of skills (skill level demand). Each country’s labor force and sectors are divided into three categories (i) low-skilled (less than secondary education), (ii) semi-skilled (with secondary education), and (iii) high-skilled (with more than secondary education).Footnote 2 The index is given by the sum of the squared distances for the three skill levels for each country and over time:

where j= skill level, Sijt= percent of labor force with skill level j at time t in country i, and Mijt=percent of employees with skill level j and time t in country i.

Services as % of GDP

Services correspond to ISIC divisions 50–99 and they include value added in wholesale and retail trade (including hotels and restaurants), transport, and government, financial, professional, and personal services such as education, health care, and real estate services. Also included are imputed bank service charges, import duties, and any statistical discrepancies noted by national compilers as well as discrepancies arising from rescaling. Value added is the net output of a sector after adding up all outputs and subtracting intermediate inputs. It is calculated without making deductions for depreciation of fabricated assets or depletion and degradation of natural resources. The industrial origin of value added is determined by the International Standard Industrial Classification (ISIC), revision 3. Note: For VAB countries, gross value added at factor cost is used as the denominator.

Source: WDI.

Business Regulations

This indicator is taken from the Fraser Institute below is the description contained in the methodological annex for each of its subcomponents- that includes the original source and the scale. High values are associated with less regulations.

- i)

Administrative requirements

This sub-component is based on the Global Competitiveness Report question: “Complying with administrative requirements (permits, regulations, reporting) issued by the government in your country is (1 = burdensome, 7 = not burdensome).”

Source: World Economic Forum, Global Competitiveness Report.

- ii)

Bureaucracy costs

This sub-component is based on the Global Competitiveness Report question: “Standards on product/service quality, energy and other regulations (outside environmental regulations) in your country are: (1 = Lax or non-existent, 7 = among the world’s most stringent).”

Source: World Economic Forum, Global Competitiveness Report.

- iii)

Starting a business

This sub-component is based on the World Bank’s Doing Business data on the amount of time and money it takes to start a new limited liability business. Countries where it takes longer or is more costly to start a new business are given lower ratings. Zero-to-10 ratings were constructed for three different variables: (1) time (measured in days) necessary to comply with regulations when starting a limited liability company, (2) money costs of the fees paid to regulatory authorities (measured as a share of per-capita income) and (3) minimum capital requirements; that is, funds that must be deposited into a company bank account (measured as a share of per-capita income). These three ratings were then averaged to arrive at the final rating for this sub-component. The formula used to calculate the zero-to-10 ratings was: (Vmax − Vi) / (Vmax − Vmin) multiplied by 10. Vi represents the variable value. The values for Vmax and Vmin were set at 104 days, 317%, and 1017% (1.5 standard deviations above average in 2005) and 0 days, 0%, and 0%, respectively. Countries with values outside of the Vmax and Vmin range received ratings of either zero or 10 accordingly.

Source: World Bank, Doing Business.

- iv)

Extra payments/bribes/favoritism

This sub-component is based on the Global Competitiveness Report questions: [1] “In your industry, how commonly would you estimate that firms make undocumented extra payments or bribes connected with the following: A—Import and export permits; B—Connection to public utilities (e.g., telephone or electricity); C—Annual tax payments; D—Awarding of public contracts (investment projects); E—Getting favorable judicial decisions. Common (= 1) Never occur (= 7).” [2] “Do illegal payments aimed at influencing government policies, laws or regulations have an impact on companies in your country? 1 = Yes, significant negative impact, 7 = No, no impact at all.” [3] “To what extent do government officials in your country show favoritism to well-connected firms and individuals when deciding upon policies and contracts? 1 = Always show favoritism, 7 = Never show favoritism.”

Source: World Economic Forum, Global Competitiveness Report.

Labor market regulations

This indicator is a combination of the following subcomponents.

- i)

Hiring market regulations

This sub-component is based on the World Bank’s Doing Business “Difficulty of Hiring Index”, which is described as follows: “The difficulty of hiring index measures (i) whether fixed-term contracts are prohibited for permanent tasks; (ii) the maximum cumulative duration of fixed term contracts; and (iii) the ratio of the minimum wage for a trainee or first-time employee to the average value added per worker. An economy is assigned a score of 1 if fixed-term contracts are prohibited for permanent tasks and a score of 0 if they can be used for any task. A score of 1 is assigned if the maximum cumulative duration of fixed-term contracts is less than 3 years; 0.5 if it is 3 years or more but less than 5 years; and 0 if fixed-term contracts can last 5 years or more. Finally, a score of 1 is assigned if the ratio of the minimum wage to the average value added per worker is 0.75 or more; 0.67 for a ratio of 0.50 or more but less than 0.75; 0.33 for a ratio of 0.25 or more but less than 0.50; and 0 for a ratio of less than 0.25.” Countries with higher difficulty of hiring are given lower ratings.

Source: World Bank, Doing Business.

- ii)

Hiring and firing regulations

This sub-component is based on the Global Competitiveness Report question: “The hiring and firing of workers is impeded by regulations (= 1) or flexibly determined by employers (= 7).” The question’s wording has varied over the years.

Source: World Economic Forum, Global Competitiveness Report.

- iii)

Centralized collective bargaining

This sub-component is based on the Global Competitiveness Report question: “Wages in your country are set by a centralized bargaining process (= 1) or up to each individual company (= 7).” The wording of the question has varied over the years.

Source: World Economic Forum, Global Competitiveness Report.

- iv)

Hours regulations

This sub-component is based on the World Bank’s Doing Business “Rigidity of Hours Index”, which is described as follows: “The rigidity of hours index has 5 components: (i) whether there are restrictions on night work; (ii) whether there are restrictions on weekly holiday work; (iii) whether the workweek can consist of 5.5 days; (iv) whether the workweek can extend to 50 hours or more (including overtime) for 2 months a year to respond to a seasonal increase in production; and (v) whether paid annual vacation is 21 working days or fewer. For questions (i) and (ii), when restrictions other than premiums apply, a score of 1 is given. If the only restriction is a premium for night work and weekly holiday work, a score of 0, 0.33, 0.66 or 1 is given according to the quartile in which the economy’s premium falls. If there are no restrictions, the economy receives a score of 0. For questions (iii), (iv) and (v), when the answer is no, a score of 1 is assigned; otherwise a score of 0 is assigned.” Countries with less-rigid work rules receive better scores in this component.

Source: World Bank, Doing Business.

- v)

Mandated cost of worker dismissal

This sub-component is based on the World Bank’s Doing Business data on the cost of the advance notice requirements, severance payments and penalties due when dismissing a redundant worker with 10 years tenure. The formula used to calculate the zero-to-10 ratings was: (Vmax − Vi) / (Vmax − Vmin) multiplied by 10. Vi represents the dismissal cost (measured in weeks of wages). The values for Vmax and Vmin were set at 58 weeks (1.5 standard deviations above average in 2005) and 0 weeks, respectively. Countries with values outside of the Vmax and Vmin range received ratings of either zero or 10 accordingly.

Source: World Bank, Doing Business.

- vi)

Conscription

Data on the use and duration of military conscription were used to construct rating intervals. Countries with longer conscription periods received lower ratings. A rating of 10 was assigned to countries without military conscription. When length of conscription was 6 months or less, countries were given a rating of 5. When length of conscription was more than 6 months but not more than 12 months, countries were rated at 3. When length of conscription was more than 12 months but not more than 18 months, countries were assigned a rating of 1. When conscription periods exceeded 18 months, countries were rated zero. If conscription was present, but apparently not strictly enforced or the length of service could not be determined, the country was given a rating of 3. In cases where it is clear conscription is never used, even though it may be possible, a rating of 10 is given. If a country’s mandated national service includes clear non-military options, the country was given a rating of 5.

Source: International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance; War Resisters International, World Survey of Conscription and Conscientious Objection to Military Service; additional online sources used as necessary.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ball, L., Furceri, D., Leigh, D. et al. Does One Law Fit All? Cross-Country Evidence on Okun’s Law. Open Econ Rev 30, 841–874 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-019-09549-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-019-09549-3