Abstract

In April 2013, a 7.0 Mw earthquake struck along the Longmen Shan fault in the city of Ya’an, Sichuan Province, China, causing serious damage. The invaluable contributions of the non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in dealing with this disaster highlighted the significance of government–NGO relationships in post-disaster reconstruction and the effect this has on the efficiency and quality of post-disaster reconstruction. This paper examines government–NGO relationships (GNR) in the post-Lushan earthquake period as a multi-stakeholder collaborative problem based on organizational lifecycle perspectives through the birth, growth, stability, and saturation stages. Two-year field research was conducted in the affected areas which identified the GNR as a bridged government–NGO relationship (BGNR) during the reconstruction period, with the Ya’an service center acting as the bridging organization. The BGNR’s experience was compared to the previous Wenchuan earthquake, and the general BGNR post-disaster reconstruction situation is discussed on two dimensions: mutuality and organizational identity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Earthquakes often have a catastrophic impact, particularly in developing countries which have large populations and less earthquake-proof infrastructure (Alexander 1993). Frequent earthquakes occur mostly in active seismic fault areas (Smith and Arabasz 1991), of which the Longmen Shan fault area in southwest China is one of the world’s most active (Xu et al. 2008). According to statistical data, 18 earthquakes higher than 6 Mw have occurred in the Longmen Shan fault area in the last 365 years (Xu et al. 2015). Recently, the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake (M 8.0) resulted in 69,226 fatalities, 374,643 injured, and 17,923 missing and caused direct economic losses of about $130 billion (Xu and Lu 2012). The recent earthquake in Lushan County, Ya’an City, Sichuan Province, on April 20, 2013, had a magnitude of 7 and a focal depth of around 13 km and resulted in 200 fatalities, 11,470 injured, and 433,316 damaged housing units (Xu et al. 2016).

Reconstruction is a crucial part of disaster recovery. Successful post-earthquake reconstruction is important for psychological, physical, and economically sustainable community development and significantly reduces the vulnerability to future hazards (Paton et al. 2000; Paton 2003; Lawther 2009; Lu and Xu 2015; Lu et al. 2017). When catastrophic disasters strike, besides the government, many NGOs are also involved in the reconstruction. Generally, for reconstruction projects, governments, and NGOs have been found to have common goals and visions with respect to social sector development, particularly in health and nutrition, poverty alleviation, human resource development, environmental protection, non-formal education, and the development of women (Begum 2003; Ahmad 2001). Further, a good relationship between governments and NGOs can improve the efficiency and quality of post-earthquake reconstruction.

First, NGOs provide differentiated public services and can complement government work. Because NGOs and the government have similar post-disaster reconstruction objectives, NGOs can identify complementary areas and provide differentiated community services in areas the government does not have the capacity to deliver goods and services (Col 2007; Derthick 2007). Second, NGOs can reallocate or coordinate non-government resources and supervise effective resource utilization using targeted and flexible approaches, especially in volunteer recruitment and management. During reconstruction, NGOs are vital for the mobilization of volunteers and volunteer services (Eikenberry et al. 2007; Simo and Bies 2007). Third, NGOs can communicate with the government on the behalf of the disaster-hit people, help disadvantaged groups, support the government in providing equal social services, coordinate with the government to solve public service crises, help the people to comprehend government policies and lubricate the relationship between the government and the population (Shaw 2003; Col 2007).

However, due to their inherently different institutional characteristics, research has found that in many cases, the relationship between governments and NGOs has been poor, leading to ineffective and inefficient programs and a consequent waste of resources (Telford and Cosgrave 2007; Wood 2004; Roney 2011; McMahon 2014). Because of this confusion and lack of coordination, a reexamination of these existing government–NGO relationships in post-earthquake reconstruction is vital to ensure future effective, efficient collaborations.

In this paper, the government–NGO relationship (GNR) in the post-Lushan earthquake period was examined as a multi-stakeholder collaborative problem based on organizational lifecycle perspectives. A 2-year field research was conducted in the affected areas, and the GNR was found to be a bridged government–NGO relationship (BGNR) during the reconstruction, with the Ya’an service center acting as the bridge. The BGNR advanced experience and reasons were summarized through compared to the previous Wenchuan earthquake, and the general BGNR post-disaster reconstruction situation discussed on two dimensions: mutuality and organizational identity. This study could offer significant guidance to future bilateral collaborations in post-disaster reconstruction.

2 Literature review

2.1 The GNR in the literature

Lester Salamon (1987) claimed that in the absence of a firm theoretical basis for a GNR, strains between governments and NGOs can signify the impossibility of achieving a positive working relationship between the two sectors. Various approaches have been taken ranging from country-specific studies (McCarthy et al. 1992) to the development of comparative definitions and frameworks specific to particular research questions (Salamon and Anheier 1996) and organizational sociology (DiMaggio and Anheier 1990). These efforts all confirmed the extensive variety of organizational forms, behavior, and hence the inter-sector relationships (Coston 1998). Bebbington and Farrington (1993) developed an asymmetrical power continuum to reflect the government’s relative acceptance or resistance to institutional pluralism, the degree of formalization in the relationship, and the relative power asymmetry in the GNR. Based on the five government linkage levels (autonomy, low, moderate, high, and direction) defined by Esman and Uphoff (1984), Coston (1998) gave an overview of eight types of GNR (repression, rivalry, competition contracting, third-party government, cooperation, complementarity, and collaboration), with each of these relationships being based on several dimensions: government resistance or acceptance of institutional pluralism, government–NGO linkage, relative power relationships, degree of formality, favorability of government policy toward NGOs, and other type-specific characteristics.

GNR research can be divided into three streams. The first is the normative perspective primarily promoted by NGO advocates that posits that a GNR should seek to maximize equity and inclusiveness and be in the position to critique government practices. The normative approach advocates a larger role for NGOs and views the relationship (Brinkerhoff 2002) as being built upon democratic values that encompass participation and empowerment, and specifically promote GNR values and principles of mutual influence, equality, and reciprocal accountability (Van der Heijden 1987; Malena 1995; Smillie 1995). A second stream of the literature has emerged in response to the first stream. This reactive perspective has been illustrated in some international donor, government, and corporate materials, including mission statements, annual reports, strategic planning efforts, special reports, and project documentation (Brinkerhoff 2002). This approach describes the GNR in glowing terms in an attempt to counter past criticism, whether or not this criticism was explicitly acknowledged, and to promote better public relations. Typically, it is difficult to distinguish the public relations objectives from actual practice without a more critical view of the subsequent results (World Bank 1996; USAID 1997; Shell International 1998).

The third stream focuses on pragmatic analyses. Generally, these studies have viewed the GNR as instrumental, that is, a means to reach other objectives related to effectiveness, efficiency, and responsiveness, and have considered particular types of government–NGO relationships or donor–NGO relationships and purposes (Bell and Shea 1998; Charles et al. 1998). These studies have been informative in a general sense, but have been analytically weak, have overlooked many of the constraints and opportunities associated with the GNR and have offered little discussion on how to improve GNR effectiveness. For example, Gazley (2010) discussed the multiple potential advantages and disadvantages in the GNR from institutional, economic, sociological and source perspectives to determine the factors that might inhibit NGOs from collaborating with local government agencies.

These studies tend to be based on areas such as network theory, the political economy, and new public management and governance models and examine inter-organizational relations, particularly those between the public and private sectors (Agranoff and McGuire 1999; Bogason and Toonen 1998; Machado and Burns 1998). Network theory, in particular, is highly analytical and includes rigorous identification and examination of inter-organizational coordination challenges, incentive systems, control mechanisms, and structural alternatives (Brinkerhoff 2002). Kapucu (2006) claimed that forming and developing inter-organizational networks was a response to the multifaceted nature of complex problems between government and NGOs which were difficult to conceptualize and analyze and were thus immune to simple solutions. Shaw (2003) identified eight main characteristics (trust, flexibility, understanding, balance of power, shared mission, compatibility, communication, and commitment) for successful GNR networks and provided some feasible suggestions regarding each characteristic for the formation and development of successful networks. Brinkerhoff (2002) developed a partnership model, which included two dimensions: mutuality and organizational identity: to analyze the networks between governments and NGOs. Mutuality encompasses the spirit of GNR principles, such as mutual dependence, and requires each actor to willingly give respective rights and responsibilities to the others (Kellner 1999). Organizational identity refers to the distinctive and enduring qualities of a particular organization which drive the rationale for selecting particular partners, with the maintenance of the relationship being seen as value-added (Brinkerhoff 2002).

2.2 The GNR in the earthquake context

In complex and turbulent disaster environments such as earthquakes, organizations frequently develop formal or informal relationships so as to work together to pursue shared goals and address common concerns (Kapucu 2007). As earthquakes differ from routine events because of the need for critical and timely information and the high level of uncertainty, effective reactions significantly test the relationships between public, private, and non-profit sector organizations (Comfort 1999). Therefore, effective and efficient earthquake responses require a comprehensive, in-depth relationship between government and NGOs.

In recent earthquakes, good government and NGO relationships have improved the efficiency and quality of post-earthquake reconstruction. For example, after the 1995 Kobe earthquake in Japan, the government and NGOs took part in societal structural reconstruction (Shaw and Goda 2004), after the 1999 Turkish earthquake, engaged in permanent housing projects together (Johnson 2007), after the 2001 Gujarat earthquake, crafted, planned, and implemented an informal housing recovery program to meet the land tenure and housing needs of squatter households within the town’s municipal limits (Mukherji 2016), and after the 1994 Northridge earthquake, established progressive working relationships with city, county, and federal agencies using local knowledge and expertise and implemented programs that connected victims with unmet needs to diverse resources (Bolin and Stanford 1998).

However, governments and NGOs have different functions because of their different institutional characteristics. As shown in Table 1, there are five main reconstruction areas in which the government and the NGOs differ in terms of structure and basic institutional approaches to the post-disaster environment: areas of concern, resource availability, management, effectiveness, and contribution level. These differences can obviously lead to conflicts on the ground and hinder government–NGO collaboration.

Therefore, the relationship between governments and NGOs has been found to be generally poor, leading to ineffective and inefficient programs and a consequent waste of resources (Telford and Cosgrave 2007; Wood 2004; Roney 2011; McMahon 2014). This was evident in the 2003 Bam earthquake reconstruction, in which a lack of cooperation resulted in a significant waste of resources. An official from the Iranian Ministry of Health said that while they were desperately focusing on psychological recovery, over 100 international NGOs requested individual meetings, adding to the confusion (Wood 2004). There was also poor communication in the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake reconstruction effort, whereby the local governments ignored the Chinese government regulations regarding NGO cooperation, so when an NGO sought permission from the relevant government ministry to become involved, they were told that if they stopped asking, the ministry would not have to refuse them (Roney 2011). With this temporary relaxation on oversight, the NGOs were afforded the space to collaborate with the local governments in an informal partnership. However, these efforts were largely ineffective because of general distrust and unfamiliarity; consequently, there were many imbalanced and unfocused activities in the affected regions, which not only influenced reconstruction efficiency and quality but also limited NGO development.

In addition, NGOs usually have geographically limited services, are spatially fragmented, often exclude important subpopulations (Lake and Newman 2002), are sometimes inherently undemocratic, and are unaccountable to the populations they are serving (Harvey 2005). In the 2010 Haiti earthquake, NGOs operated within a precise set of legal, economic and political restrictions that have variously been described as too lenient or too obstructive, meaning that many failed to meet many their most important long-term objectives (McMahon 2014).

2.3 Collaboration theory

Collaboration has been seen as a prerequisite to the sustainability of interagency programs (Gajda 2004; Frey et al. 2006), particularly for programs (such as post-earthquake reconstruction) initially created with the support of time-limited funding sources. Because there is often time pressure on each stakeholder to complete post-disaster housing projects and restore normalcy as soon as possible (Olshansky 2006), success requires partnerships between representatives from many local government departments, a wide variety of non-government groups as well as community residents and organizations; therefore, effective collaboration is critical and can play a key role in facilitating the success of the reconstruction effort.

Networking is one of the most common and effective methods for the construction of a collaborative platform between different stakeholders (Girvan and Newman 2002; Borgatti and Foster 2003; Radicchi et al. 2004). The stakeholders involved in post-disaster reconstruction projects, no matter whether they are individuals or organizations, are part of the collaborative networks through which information, knowledge and funds are circulated.

A conceptual framework was sought to theoretically describe the collaborative levels between the various stakeholders. Hogue’s (1993) five-stage model for community linkage levels was chosen as the theoretical foundation (Table 2). In addition to Hogue’s five collaborative levels, it was possible that some stakeholders had no direct interaction with others, so this possibility was reflected in the final instrument by allowing respondents to answer “no interaction”.

3 Research method

Based on field research and a literature review, this paper studied the relationship between the government and NGOs in the aftermath of the Lushan earthquake (see Fig. 1). First, historical data were collected from a literature review, policy papers, program reports and registers, job logs and other related published or unpublished third-party evaluation reports.

Second, observed data from a 2-year field research project in Lushan were collated, in which both qualitative and quantitative methods were used. To research the government–NGO post-Lushan earthquake reconstruction relationship, nine typical NGOs and nine provincial and local government departments were selected for a tracking survey, each of which had different scales and operated in different locations and areas (see Table 3). The Social Organization Authority of Sichuan Province, the Sichuan Disaster Reduction Committee Office, and the Ya’an earthquake relief headquarters were the provincial government representatives; the Communist Youth League Committee Office of Ya’an City, the Housing Construction Department of Tianquan County, the Civil Affairs Department of Lushan County, the Civil Affairs Department of Baoxing County, the Housing Construction Department of Shimian County, and the Communist Youth League Committee Office of Minshan County were the local government representatives; the China Foundation for Poverty Alleviation (CFPA), One Foundation (OF), the Narada Foundation (NF), the China Social Entrepreneur Foundation (CSEF), and the China Youth Development Foundation (CYDF) were the National NGO representatives; Shanghai Roots & Shoots (SRS) and the One Day Social Service Center (ODSSC) were the large-scale local NGO representatives; and IYouShe (IYS) and Cloud for Public Good (CPG) were the small-scale local NGO representatives.

For the quantitative section, thirty tracked survey stakeholders were asked to complete a self-assessment questionnaire and a semi-structured interview every month. The self-assessment questionnaire used the six-collaboration-level model to translate the linguistic terms into quantifiable data (Table 4 is an example of the Narada Foundation), after which a group aggregation method was used to avoid the impact of differently experienced interviewees speaking on behalf of the same group.

The qualitative section was primarily made up of the researchers’ field notes and interviews with stakeholders. The relationship cores (governments and NGOs) were the collaborative positive personal relationships between the individuals in the groups and the effective emotional connections between the partners (Gajda 2004; Frey et al. 2006). Therefore, in the semi-structured interviews, a “half-individual and half-group” interview guideline was designed, in which respondents were asked to report as individuals for half the questions and report as representatives of their groups or as a combination of roles for the other half. Using grounded analysis (Strauss and Corbin 1998), we analyzed the data line by line. In the open coding stage, we logged all collected information according to its present state, and in the axial coding stage, we discovered and established the various relationships in conceptual categories so as to establish the organic connections between the parts. Finally, in the selective coding stage, we selected “core classes” to represent all found categories to further focus the analysis.

Finally, by combining the collected historical and observed data, a stage analysis was developed for the post-Lushan earthquake reconstruction relationship between the governments and NGOs, with further analysis being done for each stage using social network analysis.

4 The Ya’an service center

The Chinese government had already begun attaching importance to the NGOs because of their excellent performance and outstanding contribution to the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake reconstruction. China’s first official white paper on disaster prevention, published on May 11, 2009, to mark the first anniversary of the Wenchuan earthquake, revealed a number of these changes. The white paper suggested that the government should strengthen “social mobilization mechanisms” so as to “give full play to the functions of non-government organizations and organizations at the grassroots level as well as to volunteers in the sphere of disaster relief.” This ensured that in the Lushan earthquake, the NGOs were given a relatively loose policy environment in which to operate.

In addition, after the Lushan earthquake, academic institutions such as Sichuan University and Beijing Normal University proposed the establishment of an intermediate organization to promote and manage the collaboration between the government and the NGOs, to which the NGO alliances and the provincial and local governments responded positively and provided strong support. Therefore, the “Ya’an civil social organization and volunteer service center for earthquake relief” (shortened to the Ya’an service center) was established for the first time to act as a bridge between the representative governments (national, provincial, and local) and the NGOs, and the newly bridged government–NGO relationship (BGNR) was formed. In the Ya’an service center, the key stakeholders (provincial and local government and NGOs) are required to establish their resident offices and dispatched permanent representatives to form a decision-making board that had tripartite interests.

The Ya’an service center had a three-level mode, with the top-level service center being located in Ya’an and 7 secondary service centers and 26 service stations distributed across the affected areas (Fig. 2). The top-level service center had reception, service, project and general departments, which were mainly responsible for directing the secondary service centers in such areas as the collection, aggregation and dissemination of information, the recruitment, training and dispatch of human resources, the integration of social resources and bridging reconstruction projects and the registration and guidance of civil organizations, NGOs and volunteers. The secondary service centers ensured that the information flow between the top-level service center and the service stations was timely and accurate and that there was sufficient supervision and guidance at the service stations to complete the projects.

The service stations were widely distributed across the affected areas and were mainly responsible for the collection and reporting of objective information that reflected the real situation on the ground and the needs of the affected areas to ensure project progress. This three-level mode allowed for both a horizontal expansion (26 service stations covering the entire disaster area) and a longitudinal extension (three-level organizational structure) of the organizational system through the erection of a platform or bridge on which the governments and NGOs were able to effectively collaborate in earthquake relief and reconstruction activities.

As of May 2015, the Ya’an service center had contacted and cooperated with 232 NGOs and 3,529 volunteers and had 38 NGO members such as the China Foundation for Poverty Alleviation, the China Youth Development Foundation, One Foundation, the Narada Foundation, the Tencent Foundation, and the China Children and Teenagers’ Fund. The service centers bridged 1403 social welfare projects costing around 3299 million CNY. Of these, 705 projects costing about 537 million CNY that were mainly related to employment, industrial development, education, training, community development, environmental protection, and psychological counseling were completed with NGO–center collaboration.

5 Stage analysis

The above description demonstrates the scale of the BGNR mode and its contribution to the reconstruction effort. However, similar to people and plants, each organization has its own unique organizational characteristics and lifecycles, with at least 33 different organizational lifecycle models having been recognized, each of which emphasizes different factors to explain the changing characteristics of organizations over time (Phelps et al. 2007). Greiner stated that organizations evolved through five sequential stages, each of which was followed by a revolution or transitional phase arising from a major organizational problem, and only by solving the problem inherent in each developmental stage could the organization successfully advance to a more mature stage (Greiner 1972; Quinn and Cameron 1983). Torber proposed an eight-stage lifecycle model based on the mentality of the members (Torber 1974). Beverland and Lockshin suggested that an organizational lifecycle was made up of four stages: resource gathering, production, brand building and rationalization (Beverland and Lockshin 2001).

First, while working at the Ya’an service center, we interviewed key stakeholders based on Hogue’s (1993) five collaboration levels and analyzed the correlations in the collected data. The correlation analyses for the NGOs, governments and Ya’an service center are shown in Fig. 3a. Specifically, we analyzed the correlation in the collaboration network between the first month (2013.05) and the others and drew a correlation analysis curve. From the curve, three break points can be seen, each of which shows an obvious decline compared to the front. Over the 2-year reconstruction period, the collaborative networks had four relatively independent stages: stage 1 (from 2013.05 to 2013. 08), stage 2 (from 2013.09 to 2014.04), stage 3 (from 2014.05 to 2014.12), and stage 4 (from 2015.01 to 2015.05).

Second, from the Ya’an service center job logs, NGO organizational reports, and internal government documents, we identified the bridged projects and funds used for the government–NGO collaboration over the 2-year reconstruction period. As shown in Fig. 3b, the curve shape for the bridging projects and funds was “steep–flat–steep–flat,” indicating that from an organizational capacity perspective, the Ya’an service center experienced four stages: stage 1 (from 2013.05 to 2013. 08) was the starting stage, when the number of bridged projects and funds were low; stages 2 (from 2013.09 to 2014.04) and 3 (from 2014.05 to 2014.12) moved from growth to stability as funds and project numbers grew; and in stage 4 (from 2015.01 to 2015.05), funding reached its peak and project starts flattening out, indicating stagnation.

Third, we selected social network analysis which was then used to assess the interviewee and questionnaire data. Two attributes were set for the cooperative networks in each month: collaborative depth and width, which reflected the vertical and horizontal NGO–government–Ya’an service center cooperative network. As shown in Fig. 3c, from 2013.05 to 2013.09, the Ya’an service center stakeholders began to establish collaborative relationships, after which the horizontal development (collaborative width) grew rapidly from 2013.10 to 2014.05. Longitudinal development (collaborative depth) then grew rapidly from 2014.06 to 2015.01, at which time the collaborative depth was the greatest.

Finally, by integrating the correlation analysis, organizational capacity, and the three cooperative network aspects, the BGNR mode in the post-Lushan earthquake reconstruction was found to be divided into four stages based on organizational lifecycle theory: a birth stage (from 2013.05 to 2013. 08), a growth stage (from 2013.09 to 2014.04), a stability stage (from 2014.05 to 2014.12), and a saturation stage (from 2015.01 to 2015.05), as shown in (d).

6 Social network analysis

For the social network analysis, two attributes were set for each stakeholder: width, which reflected the number of collaborative stakeholders, denoted “X”, and depth, which reflected the mean level of collaboration across all stakeholders, denoted “Y”. From the interview and questionnaire analyses, each stakeholder’s (X, Y) value at different stages was calculated from which four analysis graphs were developed. The social network analysis of the four stages is shown in Fig. 4.

In Fig. 4a, the connecting lines between the spots (stakeholders) indicate that the stakeholders reported moderate or high levels of collaboration; 0 level collaboration was not shown with lines. Line thickness was used to indicate the mean value for both stakeholders’ scores to illustrate the various collaborative levels, with thicker lines indicating higher levels of collaboration. Further, to highlight the core network, strong–weak cooperation and weak–weak cooperation were filtered out based on the mean number of lines and the mean collaborative levels (shown in the right corner). For example, in the birth stage, the Ya’an service center was in the core network as it fully cooperated with provincial and local governments, indicating that they were the backbone of the cooperative network.

Using Scott (2017), the relative local centrality of each stakeholder was measured and based on this value, Fig. 4b is established. From an analysis of the shadows on the radar graph, the cooperative gravity center and the overall collaborative levels were identified. The shadowed part of the growth stage shows the bias distributions, with the center of gravity being almost in the Ya’an service center, and provincial and local government side, indicating that the NGO participation degree was relatively low.

In Fig. 4c, each stakeholder was allocated a coordinate point, the value (X, Y) which indicated the width and depth of the stakeholder relationships (Fig. 4a), with the coordinate origin value being the mean number of lines and the mean level of collaboration. The stakeholders in the first quadrant were the core stakeholders, and the activity degree was in accordance with the stakeholder’s distance to the coordinate origin. These stakeholders, the Ya’an service center, OF, CFPA, and provincial and local governments, made greater contributions to the collaborative network in the stability stage. Conversely, the stakeholders in the third quadrant were relatively isolated stakeholders. However, these stakeholders could not be ignored as they were auxiliary to the collaborative networks.

Figure 4d shows the organizational capacity of each stage in terms of the bridged funds, bridged projects, completed funds, and completed project indexes, which indirectly reflect the activity and efficiency of the BGNR mode. For example, because the post-Lushan earthquake reconstruction was coming to an end, the organizational capacity in the saturation stage was relatively stagnant.

6.1 Birth stage

Birth is the beginning stage of the organizational lifecycle, so organizations at this stage are new, smaller, unstructured, flexible, and informal in terms of their management and operations (Tam and Gray 2016). As shown in Fig. 4 (birth stage), the cooperative network during this period was inactive and uncomplicated and the overall collaboration level was still low. Although the governments and the Ya’an service center had strong collaboration, the other stakeholders were relatively isolated.

Many NGOs have a try mentality to join the Ya’an service center and a wait-and-see attitude for future cooperation. Most stakeholders are at the first contact and cooperation stage, especially between local governments and some national NGOs. (Mr Wang from the Ya’an service center)

However, the primary objective in the birth stage is to secure the necessary resources, build support from social networks, and launch basic operations to ensure survival (Smith et al. 1985). Therefore, the provincial government provided significant support for the collaboration by implementing a relatively loose policy, commencing collaborative reconstruction projects, and providing funds; according to the State Council Office’s policies and measures of post-Lushan earthquake recovery and reconstruction, the provincial government has the right to completely arrange all kinds of donations to support NGOs in reconstruction activities. The local government also collaborated closely with the Ya’an service center, ensuring the smooth implementation of the bridged projects. Due to the support of the governments and the Ya’an service center and the passive NGO participation, the Ya’an service center successfully organized 443 bridged projects in the first four months.

We considered the overall demand from the disaster-affected areas, combined these with the master reconstruction plan, and entrusted part of the reconstruction projects to the society force. At the same time, local governments were required to provide support for these projects and actively participate in them. (The secretary of the Ya’an earthquake relief headquarters)

6.2 Growth stage

A major characteristic of high growth is the overall change in coordination, in which work processes become moderately formal and systematic (Smith et al. 1985). As shown in Fig. 4 (growth stage), the cooperative network underwent significant changes. First, they became more active and there was increased in-depth collaboration between the governments and the NGOs, and second, the collaboration channels between the NGOs had become well established and the cooperative networks had become richer and more comprehensive.

Through regular meetings and daily conversations at the Ya’an service center, we had a greater understanding of the governments’ roles and also met many of our peers with whom we could exchange experiences and learn from each other. (One Foundation Project director)

At this stage, the policies and procedures had been developed and an organizational structure had begun to emerge with clear functional contexts and task specializations (Lyden 1975; Hanks and Chandler 1994). The Ya’an service center had summarized and preliminarily developed some regulations based on previous NGO–government collaborations and NGO–NGO collaborations, which included contract administration, project management, supervision and responsibilities. These regulations allowed for more detailed and efficient supervision and management of all stakeholders and determined the organizational division of labor.

Finally, the information collection and distribution platform based at the Ya’an service center had been preliminarily established, which allowed stakeholders to gain access to resources and publicize their requirements, all of which led to the gradual formation of a multi-dimensional communication mechanism.

We could understand the characteristics of the different NGOs through the information collection and distribution platform, which allowed us to select the most suitable NGO for the project. (An officer from the Housing Construction Department in Tianquan County)

6.3 Stability stage

The stability stage arrives when an organization has a formal organizational structure and is supported by established office systems, regulations, and work documentation which allow for the development of norms and routines in the workplace (Hanks and Chandler 1994). As shown in Fig. 4 (stability stage), by this stage, a mature stable, high-density cooperative network had developed. In particular, two NGOs (OF and CFPA) appeared for the first time in the core network.

In addition, a three-level mode at the Ya’an service center had developed which allowed for both expansion (26 service stations covering the entire disaster area) and a longitudinal extension (a three-level organizational structure) of the organizational system through the erection of a platform on which the governments and NGOs were able to effectively collaborate in the reconstruction. Further, the information collection and distribution platform, supervisory system, accountability mechanisms, and regulations had been gradually perfected, the process and time for the reconstruction projects’ docking phases had been simplified, and the quality of the implementation phase had been guaranteed. By this time, the Ya’an service center had successfully organized 1392 bridged projects, of which 652 had been completed.

6.4 Saturation stage

In the last stage, organizations emphasize pattern maintenance and structural institutionalization. In general, the development pattern moves from an emphasis on innovation to stability and institutionalization (Lyden 1975). As of January 2015, more than 80% of the post-Lushan earthquake reconstruction projects and investment had been completed. The reconstruction collaborative process was coming to the end as demand for reconstruction projects in the disaster-affected areas began to decrease, so the main tasks in this stage were project completions. In addition, as per the initial operating procedures, the Ya’an service center was to be dissolved after the reconstruction. Therefore, even though stakeholder collaboration was no longer expanding, the NGO–NGO and the government–NGO collaborative efforts continued to deepen (see Fig. 4 saturation stage).

The core network had also changed as the Ya’an service center and the provincial government had dropped out and a further two NGOs had been added. These changing trends in the core network meant that the Ya’an service center, as the initial catalyst, gradually withdrew from the cooperative network when the NGO–government collaboration was stable and also reflected the provincial government’s devolution of power to the local government to ensure continuing grassroots collaboration with the NGOs in the field.

With the bridged projects gradually reducing, volunteers were reduced to about 2100 people from the initial 3299 people, and the staff had also reduced both in the top-level service center and the secondary service centers. (Mr Li from the Ya’an service center)

The information collection and distribution platform, supervisory system, accountability mechanism and regulations had by this time extended to other fields and covered more than just disaster reconstruction, which further expanded the government–NGO collaboration.

Besides the post-Lushan earthquake reconstruction, we are already preparing to collaborate with the government and other NGOs in many normal state fields. (Mr Luo from IYouShe)

7 Discussion

7.1 Comparisons and summary

From the detailed discussion above, it can be seen that each stage had its own specific context, processes, and approaches. Therefore, from this analysis, five key indexes (scales, core stakeholders, core network stability, mean number of lines, and mean collaborative level) were determined to compare the differences between the four stages (see Table 5).

As shown in Table 5, each of the four stages had different scales and durations. The stability stage had relatively high capacity and duration, which was in sharp contrast to the saturation stage. The core stakeholder and core network stability indexes indicate the stability of the cooperative network. At the beginning of the reconstruction effort (birth and growth stage), the core stakeholders were the Ya’an service center, the local government, and the provincial government, with the core network stability being relativity low, indicating the importance of the governments and the Ya’an service center at this stage as NGO participation was low. However, in the stability and saturation stages, a stable core network had developed and there was diversity in the core stakeholders, which now included NGOs. The mean number of lines and the mean level of collaboration in these two indexes indicate the cooperative network degree, and it can be seen that the stability and saturation stages had relatively high values compared with the birth and growth stages, indicating an increase in the collaborative efforts.

In summary, the birth stage had a middle yield and a relatively fragile cooperative network, realizing a qualitative change from zero to one. In the growth stage, the collaboration between the NGOs, governments, and the Ya’an service center rapidly expanded, with the mean links changing from 1.16 to 1.80, thus providing a solid foundation for next collaborative stage. The stability stage was, as expected, the most active and efficient stage, with the highest number of bridged projects and the highest use of funds. By this time, a comprehensive and in-depth cooperative network had been established. Finally, as the post-Lushan earthquake reconstruction was coming to an end, the organizational capacity at the saturation stage was relatively stagnant; however, the stakeholders in the cooperative network were not affected by this stagnancy and maintained a high participation level.

To examine the specific changes for each key stakeholder more closely, the relative local centrality of the stakeholders in each stage was measured based on Scott (2017)’s research to study the cooperative changes over time (Fig. 5).

In Fig. 5, the distribution of all the key stakeholders across all four stages and the specific changes in each key stakeholder’s cooperative effort can be seen. For example, over time, stakeholder participation steadily improved and finally stabilized. In the first three stages, the highest participation was from the Ya’an service center and the provincial government; however, this participation declined rapidly in the last stage. As the Ya’an service center was the initial catalyst, when the government–NGO collaboration was stable, it gradually withdrew from the cooperative network allowing for devolution from the provincial government to the local government to ensure continued NGO collaboration at the grassroots level.

7.2 Advanced experience and reasons

The previous Wenchuan earthquake reconstruction, which costs 861.3 billion CNY, had given the research team the opportunity to observe government–NGO efforts to change their “bad” relationships. Unlike previous post-disaster reconstruction activities in which government-based institutional obstacles had prevented NGOs from effectively participating, the Chinese government adopted a “very tolerant” attitude toward NGOs after the Wenchuan disaster. Even though the NGOs had also sought government collaboration and had actively participated in the reconstruction, these efforts did not evolve into effective collaborative relationships between the local officials and NGOs. Because previous stringent NGO registration requirements had not been relaxed, the autonomy granted to the NGOs was minimal, so the government continued to maintain “an atmosphere of low-level harassment” toward the NGO leaders and staff. As a result, the NGOs were only minimally considered in the central government’s plan for Sichuan’s reconstruction.

In the Lushan earthquake reconstruction, the Ya’an service center (bridged platform) created a more appropriate environment for government–NGO collaboration as it allowed both parties to develop cooperative relationships. The Ya’an service center also actively promoted NGO–NGO collaboration. A primary driver for collaboration is access to the key resources needed to reach the objectives (Brinkerhoff 2003), meaning that the NGOs were able to learn from each other and share key resources, thereby avoiding project duplication. For example, different NGOs may have had the same donation intentions or project objectives, but certain types of reconstruction projects were restricted. The Ya’an service center’s information sharing capabilities ensured that the NGOs were able to identify and promptly respond to any duplication. Therefore, the information sharing coordinated by the Ya’an service center significantly improved reconstruction efficiency. Finally, significant progress was made in government–NGO relationships for the Lushan earthquake reconstruction compared to the shaky relationship seen after the Wenchuan earthquake (2008, M8.0).

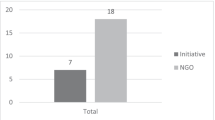

Three major changes were observed in the Lushan earthquake reconstruction. First, NGOs provided more funding assistance. NGOs had provided only 8363 million CNY or 0.97% to the Wenchuan earthquake reconstruction out of the total 861.3 billion CNY reconstruction fund. However, the Lushan earthquake reconstruction center received 3299 million CNY or 3.84% of the 86 billion CNY reconstruction fund from the NGOs. This increase in the NGO funding percentage meant that they were able to more actively participate in the reconstruction and also meant that the BGNR system improved the efficiency and scale of the reconstruction. Further, as few of the 46 NGOs were involved with project partnerships with the government for the Wenchuan earthquake reconstruction, many other small NGOs or newborn NGOs had found it difficult to establish broad partnerships with the government. When we interviewed the newly formed IYouShe and Benefit the Public (BP) NGOs, they pointed out that before, direct project partnerships with the local government were rare and some of the projects that were offered did not match their unique resources or skills. Their usual practice had been to transfer the funds to the government, thereby allowing the government to use them in accordance with the donors’ wishes. In contrast, in the Lushan earthquake reconstruction, 232 NGOs had broad partnerships with the government, including many small or new NGOs such as IYouShe, Benefit the Public (BP), and One Day For (ODF). For these NGOs, the most impressive part of the Ya’an service center was the creation of a more appropriate environment for government collaboration and the provision of projects which matched their own unique resources and skills, thus allowing them to participate more fully and deeply in the reconstruction efforts.

Second, the communication mechanism between the government and the NGOs had had a revolutionary change. A newly established NGO alliance called the “5.12 NGO Alliance,” which included 25 local NGOs, 6 international NGOs and 3 volunteer organizations, was established based on the Sichuan Youth Volunteer Program from the Wenchuan earthquake reconstruction. Each member of “5.12 NGO Alliance” elected a representative for the “5 ∙ 12 center joint meeting,” who was given the highest authority to make decisions, manage, and supervise projects, and, most importantly, coordinates with the government. This mode dramatically altered the communication mechanisms between the NGOs and improved their relationships; however, there were no significant changes in the government–NGO communication mechanism, which basically remained a one-dimensional point-to-point mode. Compared to the Wenchuan earthquake reconstruction, the Lushan earthquake reconstruction established the Ya’an service center, which had 3529 volunteers, 38 NGO members and 232 collaborating NGOs. Related government departments also established resident offices in the Ya’an service center. Therefore, in the Lushan earthquake, the governments and NGOs became integrated through the bridged platform, resulting in a multi-dimensional communication mechanism.

Third, there were significant improvements in the policy environment, supervisory systems, and accountability mechanisms. According to the deputy director of the NGO Research Institute at Tsinghua University, in the Wenchuan earthquake reconstruction, 58% of the NGOs’ funds had flowed to the government and only 42% had been labeled “self-arranged”; further, only 4.7% of the donors and one-third of the public had clearly understood where the donated funds had gone, indicating the inequality in the government–NGO relationship as well as the lack of an effective supervisory system or accountability mechanism. However, in the Lushan earthquake reconstruction, the government issued and revised some policies or regulations related to NGOs such as the State Council Office’s policies and measures of post-Lushan earthquake recovery and reconstruction, the Sichuan Earthquake Disaster Mitigation Ordinance, and The Master plan for post-Lushan earthquake recovery and reconstruction. These policies and regulations empowered NGOs by providing clearer guidelines for reconstruction participation and also limited the non-standard behavior of some local governments. Importantly, these policies provided a solid foundation for extensive collaboration. However, this more relaxed policy environment required a stricter supervisory system and a more efficient accountability mechanism. In the Lushan earthquake reconstruction, the governments and NGOs collaborated to improve the supervisory system and the accountability mechanism based on the daily collaborative work reflections (e.g., the self-discipline Alliance Convention for China Foundation). The foundation transparency index (FTI) from the China Foundation Center (CFC) found that 62% of the NGOs disclosed their funding expenditure directions. In particular, the FTI of some NGOs including One Foundation (OF), the China Foundation for Poverty Alleviation (CFPA), the China Youth Development Foundation (CYDF) was more than 90%.

7.3 The BGNR mode and implication

Coston (1998) provided an overview of the eight types of government–NGO relationships (GNR), with each of these relationships being based on several dimensions: government resistance or acceptance of institutional pluralism, government–NGO linkages, relative power relationships, degree of formality, favorability of government policy toward NGOs, and other type-specific characteristics. However, the post-Lushan earthquake relationship between the governments and the NGOs was different from these traditional types as an intermediary organization (bridged platform) was added. Intermediary organizations, or mediating structures, can facilitate collaborative relationships and can have a variety of functions such as engaging, convening, and supporting critical constituencies, promoting quality standards and accountability, brokering and leveraging resources, and promoting effective policies (Blank et al. 2003). They can also function as “change agents” to build capacity at the individual, relational, and organizational levels (Lopez et al. 2005).

The post-Lushan earthquake BGNR mode integrated the intermediary organizations and the communication platform, effectively providing a bridge between the government and the NGOs, which was a more appropriate environment for the government and the NGOs to develop a relationship. The specific structure and operations, however, were dependent on the actual situation which included such issues as reconstruction background, culture, and the overall government–NGO relationship. The improvements and advantages of the BGNR mode were manifested in the following areas.

First, the BGNR mode helped reduce the impact of the government–NGO reconstruction differences. Instead of two totally independent participants, the government and the NGOs formed a linked system using the bridged platform, which increased their interactions and reinforced system stability. Further, the frequent interactions between the government and the NGOs meant that they could screen out specific fields to allow for the attainment of common goals and to improve the openness of the BGNR mode.

Second, the BGNR mode had clear, efficient communication mechanisms. The bridged platform linked the government and the NGOs and acted as an information superhighway, which allowed the communication channels to be diverse and efficient. As the governments and NGOs were integrated on the bridged platform, they were both working toward the same goals, and therefore, the environmental and communication mechanisms shifted from a one-dimensional to a multi-dimensional mode, significantly improving overall communication. Information collection and dissemination were concentrated on the bridged platform, meaning that both the governments and the NGOs became information mediators, thus avoiding any multi-sectoral, multi-level, regional, or field limitations to the information flow.

Thirdly, the BGNR mode purified the collaborative environment. The bridged platform provided a collaborative platform on which the NGOs were able to influence policy formulation through their frequent collaborations with the government. This enabling policy environment, in turn, improved collaboration and assisted both sides to develop. In addition, the governments and the NGOs were also in a position to collaboratively improve the supervisory systems and accountability mechanisms to deal with daily problems. Experience suggests that establishing formal supervisory systems and accountability mechanisms based on agreed rules and clear procedures creates a basis for mutual respect and equality, thereby contributing to the sustainability of the collaboration.

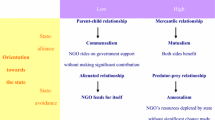

Based on the defining government–NGO partnership framework provided by Brinkerhoff (2002), the BGNR mode can be discussed on two dimensions: mutuality and organizational identity.

7.4 Mutuality

Mutuality refers to mutual dependence and requires each actor to give respective rights and responsibilities to others (Kellner 1999) to maximize the benefits of each party and ensure the meeting of joint objectives (Brinkerhoff 2002). In the BGNR mode, the governments and NGOs had frequent communication and interactions throughout the program design, implementation, and evaluation stages. Compared to simpler supplier or production contracting models, joint value was integrated in the reconstruction partnership. As the governments and NGOs were integrated on one platform, face-to-face communication was possible, which is considered the richest form of communication as it allows for multiple cues (e.g., voice inflection, body language) to facilitate shared meaning and ensures rapid mutual feedback about personal feelings and emotions (Daft et al. 1987).

Further, the government and NGOs were equal in the collaboration, as opposed to being dominated by one or more stakeholders. All stakeholders had the opportunity to influence the reconstruction objectives, processes, outcomes, and evaluations. The BGNR system mode allowed for connections between research and practice and policy and practice, as well as facilitating the ability for collaborators to meet and address shared concerns (Austin et al. 1999). Therefore, there were continual improvements to the policy and legal frameworks, the supervisory systems, and the accountability mechanisms.

Finally, the BGNR mode encouraged the government and the NGOs to be interdependent, as opposed to the previous sequential dependence. The NGOs required financial and material resources from the governments and, more importantly, required legal and institutional frameworks to work within, whereas the governments often needed the NGOs to play important intermediary and social mobilization roles in the locally affected communities, as the NGOs were often more flexible, responsive, and innovative.

7.5 Organizational identity

Organizational identity refers to the distinctive and enduring qualities of a particular organization (Brinkerhoff 2002). The key is not to maintain the organizational systems, processes, and strategies over time, but to maintain their core values and constituencies (Gagliardi 1986). It is generally believed that the creation and maintenance of organizational identity is essential to long-term success (Gioia et al. 2000; Albert and Whetten 1985). Governments and NGOs have their own missions, values, and identified constituencies to which they are accountable and responsive. However, through the rich communication channels and equal decision-making mechanisms in the BGNR system, the governments and NGOs were often matched with others who shared the same missions and core values, allowing them to pursue their respective missions while maintaining their organizational identity. This was especially important for the NGOs, as they tend to define their value in terms of their mission rather than their financial performances (Moore 2000). The opportunity to equally participate and influence outcomes meant that each actor was more easily able to protect their organizational identity and reap the efficiency, effectiveness, and synergistic rewards of the partnership.

The BGNR system also reinforced organizational identity as it empowered the governments and NGOs to elaborate on their own distinct advantages, skills, and legitimacy while being given the opportunity to understand and accept the other stakeholders’ organizational identities, thus allowing the stakeholders to more easily propose new, more effective approaches. For instance, when the governments understood the NGOs project experiences and the speed at which they were able to mobilize resources, they were more able to see how the NGOs could complement the government efforts, increasing the effectiveness and extent of the government resources, thus avoiding the risk of failure when the government wanted to replicate successful NGO projects on a much larger scale. The NGOs also learnt how to work within government processes, to coordinate activities across different groups and to transmit information about their activities and needs to a wider audience through the extensive use of the internet and the media.

References

Agranoff R, McGuire M (1999) Managing in network settings. Rev Policy Res 16(1):18–41

Ahmad MM (2001) The state, laws and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in Bangladesh. Int J Not-for-Profit Law 3(3). http://www.icnl.org/JOURNAL/vol3iss3/ar_ahmad.htm

Albert S, Whetten DA (1985) Organizational identity. In: Cummings LL, Staw BM (eds) Research in organizational behavior, Vol 7. JAI Press, Greenwich, CT, pp 263–295

Alexander DE (1993) Natural disasters. Springer, New York

Austin MJ, Martin M, Carnochan S, Goldberg S, Berrick JD, Weiss B, Kelley J (1999) Building a comprehensive agency-university partnership: a case study of the Bay Area Social Services Consortium. J Community Pract 6(3):89–106

Bebbington A, Farrington J (1993) Governments, NGOs and agricultural development: perspectives on changing inter-organisational relationships. J Dev Stud 29(2):199–219

Begum A (2003) Government–NGO interface in development management: experiences of selected collaboration models in Bangladesh. AH Development Publishing House

Bell CR, Shea H (1998) Dance lessons: six steps to great partnerships in business & life. Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Oakland

Beverland M, Lockshin LS (2001) Organizational life cycles in small New Zealand wineries. J Small Bus Manag 39(4):354

Blank MJ, Brand B, Deich S, Kazis R, Politz B, Trippe S (2003) Local intermediary organizations: connecting the dots for children, youth, and families. Washington, DC, Institute for Educational Leadership. http://www.communityschools.org/

Bogason P, Toonen TA (1998) Introduction: networks in public administration. Public Adm 76(2):205–227

Bolin R, Stanford L (1998) The Northridge earthquake: community-based approaches to unmet recovery needs. Disasters 22(1):21–38

Borgatti SP, Foster PC (2003) The network paradigm in organizational research: a review and typology. J Manag 29(6):991–1013

Brinkerhoff JM (2002) Government-nonprofit partnership: a defining framework. Public Adm Dev 22(1):19–30

Brinkerhoff JM (2003) Donor-funded government—NGO partnership for public service improvement: cases from India and Pakistan. Voluntas 14(1):105–122

Charles CL, McNulty S, Pennell JA (1998) Partnering for results: a user’s guide to intersectoral partnering. RECON (20010020170)

Col JM (2007) Managing disasters: the role of local government. Public Adm Rev 67(s1):114–124

Comfort LK (1999) Shared risk: complex systems in seismic response. Pergamon, Oxford

Coston JM (1998) A model and typology of government-NGO relationships. Nonprofit Volunt Sect Q 27(3):358–382

Daft RL, Lengel RH, Trevino LK (1987) Message equivocality, media selection, and manager performance: implications for information systems. MIS Q 11(3):355–366

Derthick M (2007) Where federalism didn’t fail. Public Adm Rev 67(s1):36–47

DiMaggio PJ, Anheier HK (1990) The sociology of nonprofit organizations and sectors. Ann Rev Sociol 16:137–159

Eikenberry AM, Arroyave V, Cooper T (2007) Administrative failure and the international NGO response to Hurricane Katrina. Public Adm Rev 67(s1):160–170

Esman MJ, Uphoff NT (1984) Local organizations: intermediaries in rural development (No. 334.683 E76). Cornell University Press

Frey BB, Lohmeier JH, Lee SW, Tollefson N (2006) Measuring collaboration among grant partners. Am J Eval 27(3):383–392

Gagliardi P (1986) The creation and change of organizational cultures: a conceptual framework. Organ Stud 7(2):117–134

Gajda R (2004) Utilizing collaboration theory to evaluate strategic alliances. Am J Eval 25(1):65–77

Gazley B (2010) Why not partner with local government? Nonprofit managerial perceptions of collaborative disadvantage. Nonprofit Volunt Sect Q 39(1):51–76

Gioia DA, Schultz M, Corley KG (2000) Organizational identity, image, and adaptive instability. Acad Manag Rev 25(1):63–81

Girvan M, Newman ME (2002) Community structure in social and biological networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci 99(12):7821–7826

Greiner LE (1972) Evolution and revolution as organizations grow. Harv Bus Rev 76(3):373–387

Hanks SH, Chandler G (1994) Patterns of functional specialization in emerging high tech firms. J Small Bus Manag 32(2):23

Harvey D (2005) NeoLiberalism: a brief history. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Hogue T (1993) Community-based collaboration: community wellness multiplied. Oregon Center for Community Leadership, Oregon State University, Corvallis

Johnson C (2007) Impacts of prefabricated temporary housing after disasters: 1999 earthquakes in Turkey. Habitat Int 31(1):36–52

Kapucu N (2006) Public-nonprofit partnerships for collective action in dynamic contexts of emergencies. Public Adm 84(1):205–220

Kapucu N (2007) Non-profit response to catastrophic disasters. Disaster Prev Manag: Int J 16(4):551–561

Kellner P (1999) A philosophy for a fallible world. New Statesman 129(4428):xxii–xxxv

Lake RW, Newman K (2002) Differential citizenship in the shadow state. GeoJournal 58(2–3):109–120

Lawther PM (2009) Community involvement in post disaster re-construction case study of the British red cross Maldives recovery program. Int J Strateg Property Manag 13(2):153–169

Lopez ME, Kreider H, Coffman J (2005) Intermediary organizations as capacity builders in family educational involvement. Urban Educ 40(1):78–105

Lu Y, Xu J (2015) NGO collaboration in community post-disaster reconstruction: field research following the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake in China. Disasters 39(2):258–278

Lu Y, Xu D, Wang Q, Xu J (2017) Multi-stakeholder collaboration in community post-disaster reconstruction: case study from the Longmen Shan Fault area in China. Environ Hazards 1–22. doi:10.1080/17477891.2017.1351914

Lyden FJ (1975) Using Parsons’ functional analysis in the study of public organizations. Adm Sci Q 20(1):59–70

Machado N, Burns TR (1998) Complex social organization: multiple organizing modes, structural incongruence, and mechanisms of integration. Public Adm 76(2):355–386

Malena C (1995) Relations between northern and southern non-governmental development organizations. Can J Dev Stud 16(1):7–30

McCarthy KD, Hodgkinson VA, Sumariwalla RD (1992) The nonprofit sector in the global community: voices from many nations (No. 658.74 MAC. CIMMYT)

McMahon SM (2014) The owners of humanitarianism: the role of nongovernmental organizations in Haitian underdevelopment. Berkeley Undergrad J 27(1). http://escholarship.org/uc/item/83q3168w

Moore MH (2000) Managing for value: organizational strategy in for-profit, nonprofit, and governmental organizations. Nonprofit Volunt Sect Q 29(suppl 1):183–208

Mukherji A (2016) Resilience at the margins: informal housing recovery in Bachhau, India, after the 2001 Gujarat quake. Int J Housing Policy 1–24. doi:10.1080/14616718.2016.1219648

Olshansky RB (2006) Planning after hurricane Katrina. J Am Plan As 72(2):147–153

Paton D (2003) Disaster preparedness: a social-cognitive perspective. Disaster Prev Manag: Int J 12(3):210–216

Paton D, Smith L, Violanti J (2000) Disaster response: risk, vulnerability and resilience. Disaster Prev Manag: Int J 9(3):173–180

Phelps R, Adams R, Bessant J (2007) Life cycles of growing organizations: a review with implications for knowledge and learning. Int J Manag Rev 9(1):1–30

Quinn RE, Cameron K (1983) Organizational life cycles and shifting criteria of effectiveness: some preliminary evidence. Manag Sci 29(1):33–51

Radicchi F, Castellano C, Cecconi F, Loreto V, Parisi D (2004) Defining and identifying communities in networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101(9):2658–2663

Roney B (2011) Earthquakes and civil society: a comparative study of the response of China’s nongovernment organizations to the Wenchuan Earthquake. China Inf 25(1):83–104

Salamon LM (1987) Of market failure, voluntary failure, and third-party government: toward a theory of government-nonprofit relations in the modern welfare state. Nonprofit Volunt Sect Q 16(1–2):29–49

Salamon LM, Anheier HK (1996) The emerging nonprofit sector: an overview (vol 1). Manchester University Press, Manchester

Scott J (2017) Social network analysis. Sage, Newcastle

Shaw MM (2003) Successful collaboration between the nonprofit and public sectors. Nonprofit Manag Leadersh 14(1):107–120

Shaw R, Goda K (2004) From disaster to sustainable civil society: the Kobe experience. Disasters 28(1):16–40

Shell RD (1998) Profits and principles—does there have to be a choice. The Shell report—1998. Shell International, London

Simo G, Bies AL (2007) The role of nonprofits in disaster response: an expanded model of cross-sector collaboration. Public Adm Rev 67(s1):125–142

Smillie I (1995) The alms bazaar: Altruism under fire-non-profit organizations and international development. IDRC, Ottawa, ON, CA

Smith RB, Arabasz WJ (1991) Seismicity of the intermountain seismic belt. In: Slemmons DB, Engdahl ER, Zoback ML, Blackwell DD (eds) Neotectonics of North America. Geological Society of America, Boulder, CO, pp 185–228

Smith KG, Mitchell TR, Summer CE (1985) Top level management priorities in different stages of the organizational life cycle. Acad Manag J 28(4):799–820

Strauss A, Corbin J (1998) Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Sage

Tam S, Gray DE (2016) What can we learn from the organizational life cycle theory? A conceptualization for the practice of workplace learning. J Manag Res 8(2):18–30

Telford J, Cosgrave J (2007) The international humanitarian system and the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunamis. Disasters 31(1):1–28

Torber WR (1974) Pre-bureaucratic and post-bureaucratic stages of organization development. Interpers Dev 5:1–25

USAID (1997) NPI Resource Guide: New Partnerships Initiative. A Strategic approach to development Partnering. New Partnerships Initiative, USAID: Washington, DC

Van der Heijden H (1987) The reconciliation of NGO autonomy, program integrity and operational effectiveness with accountability to donors. World Dev 15:103–112

Wood J (2004) Improving NGO coordination: lessons from the Bam earthquake. Humanitarian Exchange 27:27–30

World Bank, Participation & NGO Group (1996) The World Bank’s partnership with nongovernmental organizations. World Bank Publications

Xu J, Lu Y (2012) Meta-synthesis pattern of post-disaster recovery and reconstruction: based on actual investigation on 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. Nat Hazards 60(2):199–222

Xu Z, Ji S, Li H, Hou L (2008) Uplift of the Longmen Shan range and the Wenchuan earthquake. Episodes 31(3):291–301

Xu J, Xie H, Dai J, Rao R (2015) Post-seismic allocation of medical staff in the Longmen Shan fault area: case study of the Lushan Earthquake. Environ Hazards 14(4):289–311

Xu J, Xu D, Lu Y (2016) Resident participation in post-Lushan earthquake housing reconstruction: a multi-stage field research method-based inquiry. Environ Hazards 15(2):128–147

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Project of Propaganda Department of People’s Republic of China (No. 2016zybw03), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 71704124), Humanity and Social Science Youth Foundation of Ministry of Education of China (Grant No. 17YJC630096), and the Research Funding of Sichuan University (Grant Nos. skqy201640; 2016SCU11036). We appreciate this support both in finance and in spirit.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, J., Xu, D., Lu, Y. et al. A bridged government–NGOs relationship in post-earthquake reconstruction: the Ya’an service center in Lushan earthquake. Nat Hazards 90, 537–562 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-017-3056-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-017-3056-3