Abstract

Identifying the risk factors for individual differences in age-related cognitive ability and decline is amongst the greatest challenges facing the healthcare of older people. Cognitive impairment caused by “normal ageing” is a major contributor towards overall cognitive deficit in the elderly and a process that exhibits substantial inter- and intra-individual differences. Both cognitive ability and its decline with age are influenced by genetic variation that may act independently or via epistasis/gene-environment interaction. Over the past fourteen years genetic research has aimed to identify the polymorphisms responsible for high cognitive functioning and successful cognitive ageing. Unfortunately, during this period a bewildering array of contrasting reports have appeared in the literature that have implicated over 50 genes with effect sizes ranging from 0.1 to 21%. This review will provide a comprehensive account of the studies performed on cognitively healthy individuals, from the first study conducted in 1995 to present. Based on current knowledge the strong and weak methodologies will be identified and suggestions for future study design will be presented.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cognition is our ability to reason, understand, learn and adapt. Measures of cognition, such as tests of memory, processing speed, fluid intelligence (novel problem solving) and verbal comprehension, can be extremely diverse and yet the majority of these tests are highly correlated. More than a century ago Charles Spearman used factor analysis to derive a single measurement from different cognitive test scores which he coined “general cognitive ability” (also known as “general intelligence” or simply “g”) (Spearman 1904). This factor accounts for approximately half of the observed variation in human intelligence and represents one of the most replicated findings in psychology (Deary 2001). For the majority of our adult lives this ability tends to remains relatively stable. However, after approximately fifty years of age there is a gradual decline, caused by either pre-dementia or the normal ageing process, which eventually results in differing degrees of cognitive impairment (Rabbitt and Lowe 2000). Severe cognitive impairment in the elderly is an increasing problem for developed countries and one that carries with it high personal, social and economic burdens (Tannenbaum et al. 2005; Comas-Herrera et al. 2007). Cognitive genetic research is one of a host of disciplines that include imaging, proteonomics and metabolomics, that eventually hope to converge in elucidating the biological basis of successful cognitive ageing. The role that genetic variation plays in determining cognitive ability and its eventual decline in the elderly is a compelling one with extensive twin studies indicating that heritability accounts for half of the inter-individual variation observed in cognitive functioning and approximately one third of the variance in cognitive decline (Bouchard and McGue 2003; Finkel et al. 2005).

The brain reserve capacity hypothesis predicts higher intelligence to be protective against cognitive impairment in later life (Mori et al. 1997). Certainly to date the majority of cognitive genetic studies have opted for the measurement of intelligence at a single time point which is considerably cheaper, quicker and easier than their longitudinal counterparts. Whilst the genetic contribution towards cognitive decline is equally interesting, extracting meaningful data from longitudinal studies is a much more arduous task. Confounders such as variation in the decline of different cognitive domains, practice effects, selective drop-out and attrition, mean that large cohorts with a substantial follow-up and appropriate analytical adjustments are required to tease out associated polymorphisms (Rabbitt et al. 2004a).

Unfortunately, to date our knowledge of genes involved in cognitive variation has been limited by the discovery of small effect sizes and lack of replication. The purpose of this review is therefore to discuss the findings of cognitive genetic research undertaken on healthy individuals over the past fourteen years, to attempt to gauge the credibility of these studies given current knowledge and to identify appropriate study designs for future research. Discussion regarding the “intelligence” phenotype and its heritability will not be covered in any detail here and those with interest should refer to the recent and excellent review given by Deary and colleagues (Deary et al. 2009). Instead, this review will focus on a selection of cross-sectional and longitudinal genetic findings taken from over 200 published reports and will attempt to identify the more credible information pertaining to cognitive functioning. Due to the extensive number of genes currently investigated they have been divided into broad categories of neurotransmitter, disease/disorder, developmental and metabolic. Genes can have multiple functions and therefore this categorisation will never be perfect but for ease of purpose it is necessary. As well as the importance of single polymorphisms in cognition, it is also becoming apparent that the detection of epistasis/gene-environment interactions and small genetic effect sizes will be essential to increase further knowledge. This introduces new problems relating to study power that will demand new strategies for study design, necessitate collaboration and require focused funding for larger multidisciplinary projects.

Cross-sectional Cognitive Association Studies

Neurotransmitters

Neurotransmitters and their interactions form the basis of cognitive functioning and the close correlation between age-related cognitive decline and the decrease in several neurotransmitters and their receptors are well-documented (Versijpt et al. 2003; Sarter and Bruno 2004; Bäckman et al. 2006). Their potential importance in neurocognitive functioning is reflected by the fact that the investigation of neurotransmitter genes in healthy individuals accounts for two-thirds of all publications in the field of cognitive genetics and has involved the study of over 50 independent cohorts with sample sizes ranging from 50 to over 2000 (Table 1). Of these, particular attention has been given to the research of three genes, partly because previous evidence suggested a strong biological basis for their involvement in cognition and partly because they were amongst the first to be identified as containing a putative functional polymorphism. These genes comprise the dopamine receptor D2 (DRD2), catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF).

Dopamine Receptor D2

Dopaminergic neurones are especially sensitive to the effects of an age-related increase in oxidative stress. Free radical production by monoamine oxidase (major metabolic enzyme for dopamine breakdown), the high metabolic rates of dopaminergic neurones coupled with the relatively low production of antioxidants in the brain, all contribute towards increased sensitivity to damage in later life (Luo and Roth 2000). Multiple proteins within the dopaminergic system exhibit a marked decrease in expression with increasing age including the dopamine transporter, tyrosine hydroxylase and dopamine receptors (D1 and D2) that decrease approximately 4% per decade from early to late adulthood (Rinne et al. 1990; Bäckman et al. 2006). Whilst the trajectory of decline for these dopaminergic proteins have been reported as linear by many studies (Reeves et al. 2002), there are some reports that suggest the dopamine receptor D2 and the dopamine transporter show an accelerated decline beyond middle age that closely corresponds to the trajectory of cognitive decline observed in the elderly (Rinne et al. 1990; Antonini et al. 1993; Bannon and Whitty 1997; Ma et al. 1999). The reasons for the inconsistencies in determining the trajectory of loss remain unclear, although studies of this kind tend to use relatively small sample sizes and do not always use a sufficiently wide age range.

Age-related loss of dopamine receptor D2 occurs in multiple brain regions including the frontal cortex and hippocampus (Kaasinen et al. 2000) and this has been shown to have an impact on cognitive performance particularly for tests that tap into frontal brain regions such as the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test and Stroop Color-Word Test (Volkow et al. 1998). In 1995 Berman and Noble were the first to report an association between a genetic polymorphism and human intelligence when they observed an association between a functional polymorphism (TAQ1) (Comings et al. 1991) within the DRD2 gene and a test of visuospatial performance (Berman and Noble 1995). They found that participants (n = 182) carrying one or two copies of the minor A1 allele scored significantly lower on the Benton’s Judgment of Line Orientation Test than those who were homozygous for the common A2 allele.

The first attempts at replication compared TAQ1 allele frequencies of high, average and low IQ individuals (n = 50–80 in each group) (Petrill et al. 1997, Ball et al. 1998; Moises et al. 2001). Whilst all three studies observed no significant differences between genotype frequency and IQ, the Petrill study found a non-significant decrease in the A1 allele frequency for the low IQ group (17.1%) compared against the average (25.5%) and high IQ (26.5%) groups, which was an effect that went in the opposite direction to that reported by Berman and Noble. The Petrill observation was later supported by a study of Chinese girls (n = 112) where those homozygous for the A1 allele had significantly higher IQ than those homozygous for the A2 allele (Tsai et al. 2002) although the numbers of individuals in the A1/A1 (n = 15) and A2/A2 (n = 48) genotype groups were small and the significance was borderline (p-value, 0.036). However, further evidence that the TAQ1 A1 allele may be correlated with enhanced cognitive performance came in the same year when Bartrez-Faz and colleagues reported that it was associated with higher scores for both the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) and long term verbal memory, and a decrease in left caudate nucleus volume in an elderly population (mean age 66 years, n = 49) (Bartrés-Faz et al. 2002).

The reasons for the discrepancies between the original TAQ1 study and subsequent IQ studies may partially be explained by the moderate correlation between IQ and visuospatial ability (0.4), although this would not account the differences between the IQ studies which may be a consequence of inadequate sample size. However, in 2004 the evidence that genetic variation within the DRD2 gene influences cognitive ability disappeared when it was found that the TAQ1 polymorphism was not located in the DRD2 gene but 10 kilobases downstream in a gene called ankyrin repeat and kinase domain containing 1 (ANKK1) (Neville et al. 2004), which is believed to be involved in the activation of the transcription factor nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-κB) (Huang et al. 2009a). TAQ1 is in fact an SNP (rs1800497) located within a coding region of the gene where it causes a change in amino acid (glutamic acid to lysine) that prevents the translation of the gene into protein. The Huang study also identified an additional non-synonymous SNP within the ANKK1 gene (rs2734849) that altered the expression of NF-κB-regulated genes. NF-κB has recently been shown to contribute towards vascular endothelial dysfunction in the elderly, and therefore this pathway may be of interest for the study of cognitive decline in the elderly where vascular dysfunction is closely correlated with cognitive performance and white matter hyperintensities (Pierce et al. 2009; Kearney-Schwartz et al. 2009).

More recent genetic studies have examined haplotypes within a series of closely linked genes called the “NTAD cluster” that comprise NCAM1, TTC12, ANKK1, and DRD2 (Gelernter et al. 2006; Yang et al. 2008). One such study reported that cognitive outcome measures after traumatic brain injury was associated with a 3 SNP haplotype block within the ANKK1 gene that included the TAQ1 polymorphism (McAllister et al. 2008). The latest study to investigate the TAQ1 SNP in relation to cognition, and one incidentally that was incorrectly reporting a study of DRD2 rather than ANKK1, found no association with cognitive abilities (attention, working memory, learning and memory and executive function) in 84 psychosis patients and 85 healthy controls (Bombin et al. 2008). Despite the mixed findings, the TAQ1 polymorphism warrants further study. However, future research should include the entire NTAD cluster, NF-κB and related genes and consider the possibility of age-specific effects.

Catechol-O-methyltransferase

Interest in the dopaminergic pathway continued with studies of the dopamine receptors (DRD3 and DRD4), dopamine beta-hydroxylase and dopamine transporter (SLC6A3) genes. Generally, these produced a small number of mixed findings that are yet to be replicated (Table 1). By contrast, the COMT gene, which codes for the main enzyme responsible for the breakdown of dopamine, has become one of the most extensively researched in the field of cognitive genetics. A common functional polymorphism within this gene (Val158Met) has been shown to increase activity three-to-four-fold (activity increase associated with the Valine allele) (Lachman et al. 1996). This polymorphism has been investigated by over 60 cognitive genetic studies.

It has been hypothesised that an age-related loss of neurochemical and anatomical brain resources will amplify the genetic effects of polymorphisms on cognition (Lindenberger et al. 2008). In support of this hypothesis a study of young adults (mean age 25 years, n = 164) and elderly non-demented individuals (mean age 65 years, n = 154) found that the COMT Val158 allele was associated with poorer performance on executive function and working memory tasks and that the effect increased with age (Nagel et al. 2008). This work also supports the “inverted-U” hypothesis, which proposes that either hypodopaminergic (observed in ageing) or hyperdopaminergic function (observed in amphetamine stimulation) results in a shift from optimal levels required for cognitive performance (Goldman-Rakic et al. 2000). The Nagel publication also reported that “the few cognitive studies with older adults have invariably reported COMT effects in the expected direction.” Upon closer inspection the results of these studies are not particularly invariable. The first investigated episodic and semantic memory, executive function and visuospatial ability in men (n = 286, age range 35–85 years) (de Frias et al. 2004; de Frias et al. 2005). Although they found that the Val158 allele was associated with low cognitive performance, this association was observed for all age ranges and not just the elderly. In addition, the COMT/age interaction was observed for the test of visuospatial ability in middle-aged men (mean age 41 years) but not “young-old” (mean age 53 years) or “old-old” (mean age 72 years). The next cited study was by Harris and colleagues using Scottish participants (n = 460) from the Lothian region who underwent cognitive testing at 11 and again at 79 years of age. Here a significant association between the Val158Met polymorphism and cognitive ability was reported at age 79 but not at age 11. However, the heterozygous group scored higher than the homozygous groups on a test of executive function, which the authors attributed to the inverted-U hypothesis. This is in contrast to the Nagel study which observed no association with executive function. In fact, the only report that could be described as “invariable” (at least in relation to the Nagel study) was another study of Scottish elderly (Aberdeen birth cohort, n = 473) (Starr et al. 2007). Those homozygous for the Val158 allele did score lower on a measure of general cognitive ability (mean score = 33.0) compared against heterozygous (34.9) and homozygous Met158 individuals (34.9). The effect was only significant for the tests taken between the ages of 64 and 68 years but not at age 11. However, unlike the Harris study higher scores were not observed for heterozygous individuals.

The literature concerning the COMT Val158Met polymorphism and cognition is extensive, as is the breadth of differing methods, results and conclusions. Fortunately, a meta-analysis has been performed on the majority of published work up to the end of August 2007 (Barnett et al. 2008). This analysis grouped together data from 67 independent cohorts that mainly consisted of healthy individuals but also included schizophrenic and bipolar disorder patients. They then compared the genotype frequencies against measures of cognitive ability that included IQ score (21 cohorts, n = 9115), verbal fluency (12 cohorts, n = 1808), verbal recall (18 cohorts, n = 2538), Trail Making task (10 cohorts, n = 896), Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (25 cohorts, n = 2829) and n-Back Task accuracy (7 cohorts, n = 2104). The results were largely disappointing with only a suggestive indication that individuals homozygous for the Met allele scored slightly higher on IQ tests (p = 0.026; contribution of the polymorphism towards the variance in cognition observed within the cohort (effect size) = 0.1%). The IQ result was a robust one with no changes to significance when adjustments were made for sex, disease status and interestingly age. The authors concluded that the role of the Val158Met polymorphism in cognition was “little if any.” However, it should be emphasised that the advantage of an increased sample size via meta-analysis is often accompanied by problems of between-study heterogeneity and publication bias (Kavvoura and Ioannidis 2008). Meta-analysis techniques are therefore not as effective at detecting association as a suitably powered primary study.

Brain-derived Neurotrophic Factor

BDNF is a protein with several functions and is involved in neuronal differentiation (Ahmed et al. 1995), neuronal plasticity and survival (Poo 2001) and oxidative stress (Mattson et al. 2002; Wang et al. 2006, Harris et al. 2007). Similar to DRD2 there is a steady decline in BDNF expression associated with normal ageing (Hattiangady et al. 2005) and BDNF plasma concentrations have been reported as a biomarker for impaired memory and general intelligence in community-dwelling elderly (Komulainen et al. 2008). An epistasis interaction between the COMT and BDNF genes has been documented where older homozygous COMT Val66 individuals performed worse on cognitive tasks if they also possessed at least one copy of the BDNF Met66 allele (Nagel et al. 2008). Unfortunately, as with most interaction analysis this study was relatively underpowered and remains to be replicated.

An influence between the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism and cognitive abilities does at first glance appear to be reassuring given that of the twelve publications, eleven have found significant findings (Miyajima et al. 2008a). Of these, correlations with working memory have been the most inconsistent with a large study of adolescents (n = 785) failing to find any association (Hansell et al. 2007). However, the prefrontal cortex, which is involved in working memory, does not fully develop structurally or functionally until early adulthood (Fuster 2001) and BDNF mRNA are found at lower levels in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of adolescents compared to that found in adults (Webster et al. 2002). Despite this, the majority of studies have found that the Met66 allele is associated with low cognitive performance, which complements the findings of functional studies that have shown that the Met66 allele inhibits intracellular trafficking of BDNF (Egan et al. 2003; Chen et al. 2004) and is associated with hippocampal and frontal lobe grey matter volume (Bueller et al. 2006; Frodl et al. 2007; Pezawas et al. 2004).

Conversely, a study of two independent Scottish elderly cohorts (n = 471, mean age 79 years and n = 433, mean age 65 years) observed that the Met66 allele was associated with high cognitive performance on a test of executive function (Harris et al. 2006). The authors argued that whilst the Met66 allele may be damping cognition for the young and middle aged it may have a protective effect in old age. Unfortunately, these results were not replicated in a study of elderly non-demented English (mean age 63 years, n = 722) that found the Met66 allele was associated with poorer performance on several tests of cognitive ability including a test of general intelligence than in those without this gene. (Miyajima et al. 2008a). The reasons for the differences in findings are unknown although one explanation may be that the switch to a protective effect of the Val66 allele may occur between the ages of 65 and 79. Indeed, a recent study of healthy older adults (mean age 65 years, n = 53) found that at the initial point of testing the Met66 allele was associated with reduced cognitive performance (Erickson et al. 2008). A subsequent testing 10 years later of the same subjects showed a significant decrease in the trajectory of the scores for those who were homozygous for the Val66 allele. This suggests that age-related cognitive decline may be the determining factor for an apparent change in allelic susceptibility and this may be reflected by the Scottish cohorts being older than the English cohort. However, even though the mean age of one of the Scottish cohorts was 16 years older than the English volunteers the second Scottish cohort was only 2 years older and yet both Scottish cohorts showed similar results.

Another contributing factor towards contrasting results may be the complexity of the gene itself. Containing eleven exons and nine functional promoter regions BDNF is expressed in a tissue and brain region specific manner (Pruunsild et al. 2007). Expression is also regulated by a number of transcription factors and interaction between haplotypes within the RE1-silencing transcription (REST) gene and Val66Met have been reported which effect cognition (Miyajima et al. 2008b). A second functional polymorphism ((GC)n, (CA)n, dinucleotide repeat) located 1 kb upstream of the first transcription initiation site has been identified (Okada et al. 2006). Finally, BDNF mRNA forms double stranded RNA duplexes with mRNA of the antiBDNF gene (BDNFOS) which may represent another regulatory mechanism (Pruunsild et al. 2007). Overall, BDNF is a more complex gene than originally anticipated and a number of factors may have to be analysed in combination in order to untangle its true influence on cognition.

Neurological Disorders/Disease

Neurological conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), schizophrenia and the various forms of mental retardation have a genetic aetiology and cognitive impairment phenotype that makes the study of their susceptibility genes of interest for normal cognitive ageing research. The AD gene apolipoprotein E (APOE) has been intensively studied in relation to its effect on both cross-sectional and longitudinal cognition of non-demented people. A recent meta-analysis of 77 APOE studies (Jan 1993 to Aug 2008) involving 40,942 cognitively healthy subjects found that the presence of the APOEε4 allele was associated with a small but significant effect sizes (measured as mean weighted effect size (d)) of executive functioning (−.06), episodic memory (−.14), processing speed (−.07) and a global measure of cognitive ability (−.05) (Wisdom et al. 2009). An age-related increase in effect size of the APOEε4 allele on episodic memory and general cognitive ability was also observed.

Of the eleven other disease/disorder associated genes reported in normal cognition ageing (Table 2), the majority have either yet to be replicated or have produced a small number of inconsistent results. Of these, two of the more interesting associations with cognition involve the schizophrenia associated gene (dysbindin) and a progeria gene (Werner syndrome).

Werner Syndrome Gene

Werner syndrome is a rare progeroid condition, which has a prevalence of 1:200,000 in Caucasians and 1:30,000 in Japanese (Kudlow et al. 2007). The Werner syndrome gene (WRN) codes for a helicase protein which under normal circumstances proofreads DNA for errors and prevents genomic instability by unwinding complex DNA structures (triplexes, tetraplexes and RNA-DNA hybrids) (Brosh et al. 2006). Several mutations within the WRN gene result in loss of gene function which manifests as symptoms of premature ageing, including susceptibility to osteoarthritis and cancer, grey hair and skin wrinkling (Epstein et al. 1966; Goto et al. 1996; Goto 1997). Although cognitive deficit is not a typical disease manifestation of Werner syndrome the relationship between polymorphisms and cognitive functioning in non-demented elderly individuals has been explored as part of a broader study looking at the effects of WRN and normal ageing (Bendixen et al. 2004). Researchers found that an intron 1 SNP (rs2725335) was associated with general cognitive ability in elderly dizygotic twins (n = 426, aged 70–80 years). A follow-up study by the same group found that two additional WRN SNPs (rs2251621 and rs2725338) also reached significance (Sild et al. 2006). The SNPs identified by the Sild study were described as being in the 5′ untranslated region and flanking region of the WRN gene. Despite being close to the WRN gene, rs2251621 is located in the first intron of the gene purine-rich element binding protein G isoform A (PURG). The function of PURG is unknown, although its expressed protein is very similar in structure to purine-rich element binding protein A, which regulates DNA replication and transcription. A large independent elderly Dutch study (n = 1245, aged 85 years and over) found no association between three WRN SNPs (including rs2725335) and tests of processing speed and immediate and delayed memory (Kuningas et al. 2006) although this study did not investigate rs2251621 or rs2725338. They did, however, observe a marginal association between an exon 34 SNP (rs1346004) and a test of attention (p-value, 0.04). More recently, SNP rs2725335 has been associated with a test of logical memory in a sample of elderly Scottish people (n = 1063, 70 years of age) (Houlihan et al. 2009). Unfortunately, the SNP did not reach significance with other cognitive phenotypes, including attention, processing speed and memory, and the significance with logical memory disappeared after correction for multiple testing.

Despite the limited publications and borderline associations the WRN gene should still be regarded as a viable candidate for normal cognitive ageing. Future research should acknowledge that WRN is a large gene (140 kb) that requires 14 haplotype tagging SNPs (assuming a MAF ≥ 0.1 and r2 ≥ 0.8) to cover sequence spanning the first to last exons. Neighbouring genes may also be of interest, depending how far linkage disequilibrium extends, and include the upstream contrapodal PURG gene and the downstream gene Neuregulin 1 (NRG1). Interestingly, a polymorphism within the NRG1 gene (SNP8NRG243177) has been associated with decreased activation of the frontal and temporal lobes and a reduced premorbid IQ in schizophrenia patients (Hall et al. 2006) but has yet to be examined at in healthy individuals.

Dystrobrevin Binding Protein 1

The dystrobrevin binding protein 1 (DTNBP1) gene encodes a coiled-coil protein called dysbindin that forms part of a larger protein complex which conducts organelle assembly and protein trafficking (Benson et al. 2001). DTNBP1 small interfering RNA (siRNA) has been shown to increase cell surface DRD2 and block dopamine induced internalisation in human neuroblastoma and rat primary cortical neurones (Iizuka et al. 2007). Iizuka and colleagues hypothesised that polymorphisms within DTNBP1 may downregulate dysbindin and have a similar action to that caused by siRNA thus resulting in a disturbance of dopaminergic transmission and impaired cognitive performance.

DTNBP1 has been a major focus in schizophrenia research and of the 45 DTNBP1 studies listed on the schizophrenia research forum there have been 19 associations, 2 non-significant trends and 24 negative findings with meta-analysis showing significance for several SNPs (www.schizophreniaforum.org, update 27.03.2009). Varying degrees of cognitive impairment are observed in schizophrenia, and this has promoted researchers to investigate the role of DTNBP1 on this symptom domain in both schizophrenics and healthy controls. Burdick and colleagues were the first to report a correlation between DTNBP1 and a measure of general cognitive ability in both patients (n = 213) and controls (n = 126) where they found that a six locus haplotype (rs909706, rs1018381, rs2619522, rs760761, rs2619528 and rs1011313) accounted for 3% of cognitive variance in both groups (Burdick et al. 2006). A smaller study of 76 schizophrenics, 31 unaffected sibs and 31 healthy controls found an association between rs760761 and rs2619522 (both intronic and in strong linkage disequilibrium) and IQ (Zinkstok et al. 2007), which was later replicated by a larger independent study of healthy men (n = 2243) (Stefanis et al. 2007). The latest study to investigate DTNBP1 and cognition used three independent Caucasian cohorts from Scotland (n = 1054, measures at 11 and 70 years), Australia (n = 1808, mean age 16–19 years dependent upon test) and England (n = 745, mean age 63 years), all of whom had undergone a broad array of tests (Luciano et al. 2009a). Analysis of the haplotype tagSNP rs1018381 reported by Burdick showed association with a measure of general cognitive ability in the Australian cohort, a non-significant trend for logical memory in the Scottish cohort (p-value, 0.06) and reduced scores for the majority of tests taken by the English volunteers (although these failed to reach significance). Analysis of rs760761 and rs2619522 that were associated with IQ in both the Zinkstok and Stefanis reports also showed association with tests of executive function in the English and Scottish cohorts with all groups showing an effect in the same direction. Additional associations were observed in the Scottish and English cohorts for several SNPs with both memory and executive function tests that were not observed in the other cohorts and which may be due to age-specific effects. The English study also genotyped several SNPs located in the 3′ end of the gene which had not previously been investigated. Of these rs742105 was significantly associated with three separate tests memory recall (immediate, delayed and cumulative). To date one publication has found no association between polymorphisms in the DTNBP1 gene and cognitive ability (Peters et al. 2008). This study of Anglo-Irish schizophrenics (n = 336) and controls (n = 172) found no evidence that any of the 39 tagSNPs used (covering the DTNBP1 gene and 10 kb on either side) influenced cognitive measures of either patients or controls.

The results published so far are indicative that DTNBP1 may influence cognitive functioning. The approach used by the Peters study, which used tagSNPs to cover the entire gene and substantial flanking sequence should be adopted for future studies although this should be combined with the use of several large independent cohorts which was the approach used by Luciano and colleagues. In addition, the potential interaction between DTNBP1 and DRD2 is an intriguing one which remains to be explored.

Developmental

Twin studies have revealed that not only is brain volume highly heritable (0.90–0.95, frontal lobe volumes; 0.40–0.70, hippocampus) but it is also moderately correlated with working memory (r = 0.27) and processing speed (r g = 0.39) (Pfefferbaum et al. 2000; Sullivan et al. 2001; Posthuma et al. 2003; Peper et al. 2007). Although genes have been shown to influence brain volume and brain volume is correlated with intelligence, it is still unclear whether the effect is directly causal, such that genes influence volume which influences intelligence, or has an indirect effect, such that genes influence intelligence which determines volume. There also appears to be little correlation between atrophy of brain regions and cognitive ability in community-dwelling elderly once the analysis has been adjusted for whole brain volume (Shenkin et al. 2009). In the Shenkin study, intracranial area (estimator of maximum cranial volume) accounted for over six per cent of the variance in general intelligence in the elderly compared to atrophy which accounted for less than one per cent. These results indicate that developmental genes that determine brain volume may be important predictors of mental health and cognitive status in later life.

Prior to 2006 the msh homeobox 1 gene (MSX1), which acts as a transcriptional repressor during embryogenesis, was the only developmental gene associated with cognition (Fisher et al. 1999). Since then four additional genes have been reported in the literature: neuregulin1 receptor (ERBB4), which induces cellular differentiation (Nicodemus et al. 2006); kallikrein-related peptidase 8 (KLK8), which promotes neurite outgrowth (Izumi et al. 2008); S100 calcium binding protein B (S100B), which is involved in neurite extension and axonal proliferation (Lambert et al. 2007) and the neuronal scaffold protein WW and C2 domain containing 1 (WWC1) (Papassotiropoulos et al. 2006) (Table 3). Of these WWC1 (formally known as KIBRA) has been the only developmental gene to be studied by multiple independent groups.

WW and C2 Domain Containing 1

WWC1 codes for a postsynaptic scaffold protein called KIBRA that connects cytoskeletal and signalling molecules. KIBRA is mainly expressed in the hippocampus, cortex, cerebellum and hypothalamus and its expression is upregulated during early brain development suggesting it plays a role in neurogenesis and synaptogenesis (Johannsen et al. 2008). High levels of KIBRA expression are observed in the cerebellar Purkinje cells which have been implicated in learning (Thompson and Kim 1996). KIBRA has also been shown to be the substrate of protein kinase C zeta which itself is involved in long-term potentiation in the adult brain (Büther et al. 2004).

A genome wide association study (GWAS) of over 500,000 SNPs, using a pooled DNA method (n = 341, median age 22 years) followed by replication in two independent cohorts (n = 256, median age 55 years and n = 424, median age 21 years), first identified KIBRA as a regulator of memory performance (Papassotiropoulos et al. 2006). Associations between episodic memory and a T > C substitution (rs17070145) in intron 9 of the gene were observed in all three cohorts where the presence of the T allele was correlated with improved episodic memory. No association was observed for the cognitive domains of attention, concentration or working memory. This finding was later replicated by a study of healthy elderly (n = 64) (Schaper et al. 2008) and another study that included elderly volunteers (n = 312, 50–89 years) with and without mild cognitive impairment (MCI) (Almeida et al. 2008). The Almeida study also reported no difference in allele frequencies between participants with or without MCI. Nacmias and colleagues also observed the association with episodic memory in an elderly population with subjective memory complaints (n = 70, mean age 60.7 years), but they found the T allele was associated with lower episodic memory scores (Nacmias et al. 2008). The T allele has been reported as a susceptibility allele for late-onset AD (Corneveaux et al. 2009; Rodríguez-Rodríguez et al. 2009) and this may have account for the opposing findings. However, if this were the case then a difference in allele frequencies may have been expected between the MCI and non-MCI volunteers in the Almeida study and yet none was. There were also no significant differences between the genotype frequencies (CC and CT/TT) or the MMSE scores either within or between these two studies indicating that the polymorphism would not predispose towards AD in these cohorts. Finally, a comprehensive study of 39 tagSNPs within the WWC1 gene (including rs17070145) and additional SNPs extending 20 kb upstream found no association with any tests of memory in two independent cohorts (319 and 365 individuals of European origin) (Need et al. 2008). The Pappassotiropoulos study identified genetic effect sizes of up to 6.2% and both the cohorts used in the Need study had approximately 90% power to detect a 3% effect size and they included exactly the same phenotypes into their regression model as those used by Pappassotiropoulos. The reasons for the discrepancies therefore remain unclear, and larger studies with better characterised cohorts will be required to determine whether WWC1 is truly associated with cognition.

Metabolic Related Genes

Stereological studies have shown that within a healthy ageing brain there is a minimal loss of neurones in hippocampal and cortical regions (West et al. 1994; Morrison and Hof 1997). Instead, more subtle changes occur during normal ageing including shrinkage and loss of dendrites and dendritic spines, reduction in soma volume (Dickstein et al. 2007), an age-related increase in oxidative damage to lipids, proteins and DNA, a decrease in antioxidants (Dröge and Schipper 2007) and the accumulation of neurotoxic proteins (Gibson 2005). The field of ageing research has particularly focused on a number of metabolic and antioxidant genes including those in the insulin signalling pathway, sirtuins (regulators of fat and glucose metabolism in mammals), superoxide dismutase and catalase (Rodgers et al. 2005; Broughton and Partridge 2009; Harman 1956; Dröge and Schipper et al. 2007). Mutations within these “ageing genes” have been shown to dramatically increase the life-span of yeasts, nematodes, fruit flies and mice and may be expected to effect cognitive performance particularly in the elderly where oxidative damage to neurones and vasculature has had time to accumulate (Sanderson et al. 2008). However, a comprehensive study of 109 genes mainly implicated in oxidative stress (sample size 420–437) identified only a single intronic SNP (APP, rs2830102) associated with cognitive functioning in the elderly, and this remains to be replicated by independent groups (Harris et al. 2007). To date only a handful of metabolic related genes have been implicated in cognitive functioning in healthy individuals (Table 4).

Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 5 Family, Member A1

Aldehyde dehydrogenase 5 family, member A1 (ALDH5A1) (formally known as SSADH) encodes the mitochondrial enzyme succinate semialdehyde dehydrogenase that is involved in the metabolism of the inhibitory neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA). ALDH5A1 is located on chromosome 6p22 which has been identified as a region associated with dyslexia, reading ability and spelling ability (Francks et al. 2004; Cope et al. 2005; Luciano et al. 2007; Platko et al. 2008) although the finding with dyslexia has been challenged (Petryshen et al. 2000). Very rare mutations within ALDH5A1 lower expression of the enzyme and increase accumulation of GABA and 4-hydroxybutyrate which result in a range of clinical phenotypes including mild mental retardation, seizures and behavioural problems (Akaboshi et al. 2003). Several mechanisms of action have been proposed to explain the effects of ALDH5A1 on cognition, including the neurotoxicity of GABA and 4-hydroybutyrate and the influence of GABA on long-term potentiation (LTP) and synaptic inhibition (Gibson 2005; Sgaravatti et al. 2007; Marshall 2008).

An association between a functional ALDH5A1 SNP (exon 3, C358T, rs2760118), where the T allele has 18% less enzymatic activity (VMax) (Blasi et al. 2002), and IQ has been reported in high IQ children (n = 197) and their families (trio n = 104) (Plomin et al. 2004). Individuals with one or two copies of the T allele had significantly lower IQ compared to those carrying the C allele (1.5 IQ points). A later study hypothesised that the potential neurotoxicity caused by reduced ALDH5A1 may have a greater adverse effect on cognition and even survival of elderly individuals (de Rango et al. 2008). The study of 264 elderly (65–85 years) found that the distribution of the T allele was greater in those with lower cognitive functioning (MMSE ≤ 23) compared with higher functioning individuals (MMSE > 23) (p-value, 0.05) and that survival was lower for individuals with the TT genotype.

Whilst the role that metabolic and antioxidant genes play in ageing and longevity is a convincing one, there is no compelling evidence thus far that they have a substantial impact on cognition either in the young or elderly. However, current investigations of these genes have been too few, poorly powered and the majority lack replication. These issues need addressing before further conclusions can be drawn.

Longitudinal Association Studies

Determining the proportion of cognitive decline in the elderly that can be attributed to genetic variation has proved a challenge for several reasons. Firstly, cognitive abilities in healthy elderly individuals show substantial intra- and interindividual differences in decline that are caused by a number of factors including genetic and environment influences, stochastic events and disease. A study that followed over 6000 non-demented elderly volunteers for changes in cognitive ability over a twenty year period found that tests of executive functioning decline at an accelerated rate, whilst the decline of memory abilities tended to be linear and verbal abilities remained stable over time (Rabbitt et al. 2004b). The same group also found that cognitive decline is fairly gradual with executive functioning declining at an average of 6% per decade between the ages of 50 and 80 years (Rabbitt and Lowe 2000). Extensive periods of time and regular cognitive measurements are therefore required to be able to accurately estimate heritability or detect genetic effects. Consequently, a large proportion of elderly subjects tend to be lost between subsequent testing due to attrition and therefore the power of longitudinal studies tends to taper quite dramatically over time. In addition, bias can be introduced by differential survival (Glymour et al. 2008). For example high premorbid IQ scores are correlated with a reduced rate of mortality from factors such as coronary heart disease, suicide and accidents (Batty et al. 2009). Therefore, the greater the mean age of the cohort the less they will be representative of the general population and for longitudinal studies the survivors tend to be comprised of an increasingly elite and able group. Indeed, volunteers for cognitive studies in the UK are far from a randomised selection of individuals and tend to be of higher than average IQ, middle class and predominantly women (Rabbitt et al. 2004b). A further consideration is analytical adjustment for practice effects. Even though several years may have passed between testing periods volunteers have been shown to remember the questions or task strategies and therefore show an artificial improvement that varies depending upon the type of cognitive test, the participants educational background and how well they performed on a previous examination (Rabbitt et al. 2004a).

The initial twin studies investigating cognitive decline produced varied findings with heritability estimates ranging from 0.0–0.7 for fluid and 0.0–0.3 for crystallised intelligence (McArdle et al. 1998; Reynolds et al. 2002; McGue and Christensen 2002). Much of this discrepancy could be attributed to the reasons described above. Indeed, the first heritability studies were either relatively large but had a short follow-up (5–8 years) (Reynolds et al. 2002; McGue and Christensen 2002) or had a long follow-up but had only a modest sample size (134 twin pairs) (McArdle et al. 1998). Substantial attrition was also evident with an 80% loss of sample size for the McGue study between the first and last assessment which spanned just 8 years (McGue and Christensen 2002). Further variation may have been caused by the differences in cognitive tests, analytical models and population stratification effects.

A subsequent study of 778 twins (aged 50 years and over) with a follow-up of 13 years investigated the genetic and environmental affects on verbal, spatial, memory and processing speed with analysis performed on the initial ability score (intercept), the rate of decline (slope) and the acceleration of decline (quadratic) (Finkel et al. 2005). As expected a substantial genetic influence was observed on the intercept and yet it was found that the genetic contribution towards the slopes of all cognitive abilities and on the quadratic for verbal ability were “negligible”. However, the genetic effect on the quadratic for fluid abilities and processing speed accounted for approximately one third of the variance. It was also observed that the quadratic for memory and spatial abilities (but not verbal ability) was slowed by a faster mean processing speed and later work suggested that changes in processing speed pre-empt the changes in memory and spatial ability (Finkel et al. 2007). The most recent work by Finkel and colleagues used data collected at up to five measurement points over a 16 year period (Finkel et al. 2009). They found that when the processing speed factor was removed from the model a substantial proportion of the genetic variance for the spatial and memory factors also disappeared. This suggests that the genetic variance in processing speed “drives” the age-related changes in fluid abilities. Taken together these data support the processing speed theory of cognitive ageing which postulates that processing speed is integral to the performance of fluid abilities and that the constraints of processing become more evident with age (Salthouse 1996).

Genes Associated with Cognitive Decline in Healthy Individuals

Due to the difficulties of establishing adequately powered longitudinal studies with sufficient follow-up, publications tend to be fewer in number and are more prone to Type 1 and Type 2 error compared with cross-sectional studies. The handful of investigated genes include apolipoprotein E (APOE), serotonin transporter (SLC6A4), serotonin receptor 2A (HTR2A), estrogen receptors 1 and 2 (ESR1-2) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPARG). Of these only the APOE alleles ε2-ε4 have been looked at by multiple independent groups with ten out of sixteen studies reporting that APOE ε4 increased the rate of decline in non-demented elderly (Savitz et al. 2006). However, fifteen of these studies had a follow-up period ranging from 2 to 8 years with a mean follow-up of just 4.7 years and the majority had not adjusted for practice effects or investigated the quadratic independently of the slope. Assuming an average decline of 6% per decade in a sample of non-demented elderly (Rabbitt and Lowe 2000) these studies were essentially trying to determine the effect of APOE alleles on an average trajectory variance of just 2.8%.

Of the remaining associations made between polymorphisms and cognitive decline three of them (PPARG and ESR 1 and 2) were reported by the Health, Aging and Body Composition study (Health ABC study, USA) who tested elderly volunteers biannually over a four year period using the Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (3MS) and the Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST) (a measure of processing speed, attention and executive function) (Yaffe et al. 2008; Yaffe et al. 2009). The PPARG SNP rs1805192 (Pro12Ala) was selected due to its association with diabetes and obesity, both of which correlate with cognitive decline. In a large but ethnically mixed sample (n = 2961; 41% black, 52% women, age range 70–79 years), they found that the Ala polymorphism was associated with higher test scores for both the 3MS and DSST at baseline and that 17.5% of Ala carriers exhibited cognitive decline (defined as a loss of ≥5 3MS points over 4 years) compared to 25% of non-carriers (Yaffe et al. 2008). Estrogen receptor 1 and 2 polymorphisms have previously been associated with AD (Brandi et al. 1999). Therefore Yaffe and colleagues hypothesised that the same SNPs may influence cognitive decline in non-demented individuals. Again using volunteers (n = 2527; 1343 women, mean age 73 years) from the health ABC study they identified several associations with cognitive decline (Yaffe et al. 2009). Out of eight SNPs five were associated with cognitive decline in a sex specific manner, and one (ESR2, rs1256030) was associated with decline in both men and women. All except one of the SNPs were located within an intron although two SNPs (rs8179176 and rs9340799, both ESR1, intron 1) are within a region (intron 1/exon 2 boundary) that has been reported to regulate expression (Maruyama et al. 2000). However, ESR1, ESR2 and PPARG are large genes that require between 13 and 45 tagSNPs to cover the coding regions (assuming a MAF > 10%, r2 > 0.8, Caucasian population). The studies are therefore limited in both their follow-up and depth of SNP coverage.

The Swedish Adoption Twin Study of Ageing (SATSA) and the Dyne Steel cohort for cognitive genetic studies have both reported that serotonergic genes regulate the rate of cognitive decline (Reynolds et al. 2006; Payton et al. 2005). Serotonin is involved in both brain development and cognitive functioning and there is an age-related decrease in serotonin levels that may predispose to depression, cognitive impairment and dementia (van Kesteren and Spencer 2003; Meneses 1999; Rehman and Masson 2001). Reynolds and colleagues studied the longitudinal effects of a promoter polymorphism within the HTR2A gene (rs6311; −1438 G/A) on the longitudinal decline over a 13 year period using 595 elderly individuals (517 at final testing occasion, mean age 65 years at baseline testing). They found that individuals homozygous for the G allele declined slower for a test of episodic memory than those carrying the A allele which accounted for a difference in trajectory of between 2–6% per year. A non-synonymous HTR2A SNP (rs6313; H452Y), which has been shown to blunt receptor response (Göthert et al. 1998), has also been associated with variation in episodic memory that accounted for 21% of the variation of test scores measured at a single time-point (de Quervain et al. 2003). Further evidence that the serotonergic pathway is involved in cognition has come from our Manchester group where we reported that a functional VNTR within the intron 2 (MacKenzie and Quinn 1999) of the serotonin transporter also regulates the rate of cognitive decline in elderly non-demented volunteers (n = 758) all of whom had been followed for changes in cognitive performance over a 15 year period (Payton et al. 2005). We found that those who carried VNTR12 allele, that was associated with an increase in transporter transcription, declined significantly faster than those carrying the VNTR10 allele. This accounted for a 2.9% faster decline in general intelligence per decade for heterozygous individuals and 4.4% faster decline for homozygous VNTR12 individuals when compared against those homozygous for VNTR10. To date no attempts have been made to replicate the serotonin transporter or HTR2A results or to test for an interaction between these two genes.

Study Considerations

The overview of cognitive genetic research given above is one largely bereft of consensus and adequate research design. This is not necessarily a reflection upon the overall quality of research. Many previous studies were limited in scope but given the early discovery of low hanging fruit, such as the association between APOE and AD, there was no reason to believe that such large effect polymorphisms would not exist for cognition particularly when the heritability is so high. Neither is the lack of inconsistency limited to cognitive genetic studies. Indeed, a failure to replicate an initial positive finding is a common characteristic of the majority of association studies investigating complex diseases and traits (Hattersley and McCarthy 2005). Inadequate sample size, population stratification, environmental exposure, publication bias, variation in classification and measurements are all examples that may make one groups findings different from those of another. Combined with the development of high throughput techniques, and hence a dramatic increase in the number of original publications in human genetic epidemiology, the reader is now faced with a frustrating variety of results and conclusions (Lin et al. 2006). Meta-analysis goes some way to provide a solution to this problem by detecting and adjusting for inconsistency between data sets, although even this technique has several pitfalls (Kavvoura and Ioannidis 2008). Sadly however, if the question were to be asked “after 14 years of cognitive genetic research what genes can we conclusively say are responsible for the variation in cognition or its decline with age in healthy individuals?” the answer would have to be “none.” This doesn’t imply that we have not already identified intelligence genes but merely that better designed studies are required to confirm or refute which of them actually play a role in cognition and which of them do not. Listed below are a number of confounders that can result in type I and type II errors. However, a good association study should always include an independent replication cohort in its design, which would dramatically reduce the numbers of false positive publications.

MMSE as a Cognitive Screening Tool

Amidst the extensive array of cognitive measures there exist tests that are not suitable for purpose for the study of healthy people. One commonly used test for measuring cognition in the elderly is the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). The MMSE was designed over 30 years ago as a screening tool for dementia and it remains a widely used method (Folstein et al. 1975). Unfortunately, it has limitations as a measure of cognitive outcome. Primarily, it has a substantial ceiling effect which makes it impossible to differentiate between medium and high performing individuals (Tombaugh and McIntyre 1992). Studies that rely solely on the MMSE as a measure of cognitive function therefore possess a lack of sensitivity that would make the accurate detection of small effect polymorphisms much more unlikely. To help counter the shortcomings of the MMSE an extended version of the test has been developed. The Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (3MS) increases the maximum score from 30 to 100 and extends the number of questions aimed at measuring memory and executive function. Comparison of the MMSE and 3MS in a population of over 12000 elderly participants (65 years and over) in the MRC Cognitive Function and Ageing Study found that ceiling effects were reduced from almost a quarter of the volunteers (scoring 29 or 30) for the MMSE test to 9% for the 3MS test (Huppert et al. 2005). However, even a ceiling effect of 9% would ultimately influence power and may be considered to high.

Sex-specific Effects

Sex-specific differences in the prevalence of mental retardation and neuronal efficiency are well documented (Ropers and Hamel 2005; Neubauer et al. 2005). Whether differences exist for general cognitive ability remain a contentious issue (Irwing and Lynn 2005; Blinkhorn 2005; Irwing and Lynn 2006) although there appears to be no gender differences in the patterns of cognitive ageing (Finkel et al. 2006). The uncertainty for the existence of sex specific effects is reflected by the fact that only a small number of other genes in addition to ESR1 and ESR2 have been shown to exhibit a sex specific influence on cognition. The fragile X mental retardation 1 gene (FMR1; Xq27.3) contains a CGG repeat in the 5′ untranslated region which can silence the gene and cause mental retardation if the number of repeats exceeds 200 (Crawford et al. 2001). A study using 66 men and 217 women, who were divided according to their CGG repeat number, observed that women, but not men, with >50 repeats scored significantly lower (4% difference in score) on a test of verbal IQ when compared against females with less than 50 repeats (Allen et al. 2005). A sex specific effect has also been observed with the disrupted in schizophrenia 1 (DISC1) gene (Thomson et al. 2005). The study of 171 men and 254 women who had taken the Moray House IQ Test at age 11 and again at age 79 found that a non-synonymous exon 11 SNP was weakly associated with reduced scores in elderly women only (p-value, 0.043; after adjustment for ability at age 11). Whilst current evidence is not particularly strong for the existence of sex specific effects it is something that researchers should be aware of when conducting analysis.

Interactions

A common misconception about genes is that they are rigid entities that serve single functions throughout our lives. On the contrary, a single gene can perform multiple tasks at various stages of development, alter the function of other genes, act in a tissue specific manner and respond to changes in the environment. The nature versus nurture debate became so polarised during the last century that the possibility of gene-environment interaction was largely overlooked (Ridley 2003). Reports of interactions are now increasing exponentially for a wide variety of diseases and traits including cancer (Thorgeirsson et al. 2008), asthma (Kim et al. 2009) and obesity (Qi and Cho 2008). One of the first high quality publications demonstrating interaction was by Caspi and colleagues who tested why some people were susceptible to depression caused by stressful life events whilst others were not (Caspi et al. 2003). The study divided 847 participants, who had been assessed for depression and stressful life events on ten occasions between the ages of 3 and 26, into three groups according to whether they carried the short (s) or long (l) form of a serotonin transporter (5-HTTLPR) polymorphism (homozygous s/s, heterozygous s/l and homozygous l/l). They observed that individuals carrying at least one copy of the short allele (associated with reduced transcriptional efficiency) were more prone to depression and suicidality compared to those who carried two copies of the long allele, and this effect was dependent upon the number of stressful life events they had experienced. A potentially important conclusion from the authors was that multifactorial disorders may not necessarily result from many genetic variations of small effect but may be attributed to a smaller number of variations whose effects are mediated via their exposure to the environment.

To date eight studies have identified gene-environment interactions that effect cognition (Table 5). One of these studies reported that the minor alleles of two SNPs (rs1800562 and rs1799945) within the hemochromatosis gene influenced lead-related cognitive decline in non-demented elderly men (n = 358) (Wang et al. 2007). Unfortunately, this study had several limitations including the use of the MMSE as a measure of ability, a relatively small population size for interaction analysis and an inadequate time period between the two testing sessions (mean = 3.2 years). Three other gene-environment studies also had a severe lack of power due to small sample size particularly once the subjects were sub grouped (Froehlich et al. 2007; Morales et al. 2008; Johnson et al. 2008). A more convincing study found that the positive effect of breastfeeding on IQ was regulated by a common polymorphism (rs174575; CG) within the fatty acid desaturase 2 (FADS2) gene (Caspi et al. 2007). Caspi and colleagues used two independent cohorts from New Zealand (n = 1037) and the UK (n = 2232) and found that breastfed children had a significantly higher IQ (approximately 6.0 IQ points). In addition, genotype showed significant interaction with breastfeeding in both populations (New Zealand, p-value, 0.035; UK, p-value, 0.018) with the presence of the C allele increasing IQ in those who were breastfed, whilst those homozygous for the G allele showed no difference in IQ whether they were breastfed or not.

Five epistasis (gene-gene) interactions have also been reported (Table 5). BDNF as already discussed is the most consistently associated gene in cognition and yet there still exists contrasting reports regarding its function in cognition. Whilst population differences, testing methods and sample size may be contributing factors it is also necessary to consider that single polymorphisms are unlikely to act independently. An example of this is the serotonin transporter gene that has at least two functional polymorphisms and where it has been demonstrated that analysing these polymorphisms in combination is a more powerful approach than analysing them independently (Hranilovic et al. 2004). This study highlights the need for research groups to adopt a haplotype tagging approach where genetic variations are selected that capture the majority of diversity for the entire gene and surrounding regions. Of more than 200 publications in the field of cognitive genetics only 8 have adopted this method and even fewer have analysed haplotype findings in combination with other genes. One such study was performed by Miyajima and colleagues who investigated the epistatic interaction between BDNF and the REST gene which is a regulator of BDNF expression (Miyajima et al. 2008b). A haplotype within the REST gene, that contained an exon 4 hexadecapeptide variable number tandem repeat (VNTR) with either four or five copies and a non-synonymous SNP, was weakly associated with general intelligence (p-value, 0.05) in an elderly non-demented cohort (n = 746). When the REST haplotypes were analysed with BDNF haplotypes an interaction was observed (global p-value, 0.0003) that was more significant than when either gene was analysed independently. However, investigating polymorphisms in combination is a considerable drain on power and only 45 people (6%) possessed the haplotype combination associated with improved performance.

Interaction analysis is providing information that should have been obvious from the start, in that genetic variants are unlikely to act independently. Biological pathways are regulated by multiple genes, that themselves are influenced by other genes and possibly multiple genetic variants. In addition, genes act on cues from the environment. Perhaps by considering these factors in combination rather than independently a clearer picture will emerge. Interactions and sex specific effects may provide a stronger association and hence not necessarily demand an increase in sample size. However, if the effect sizes prove to be small and/or the allele of interest has a low frequency then particularly for interaction analysis this could dramatically increase cost.

Sample Size

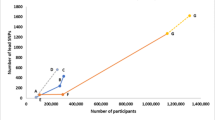

Sample size is a clear constricting factor for many of the studies described above. What constitutes an adequate sample size is open to interpretation as the calculation requires an estimate of effect size and this is yet unknown. It has been recommended that researchers should be aiming to break the “1% quantitative trait loci barrier” which requires between 800 and 1000 samples to detect a polymorphism which accounts for at least 1% of the variance in cognitive ability within the general population with 80% power (Plomin 2003; Craig and Plomin 2006). Unfortunately, as can be seen in Tables 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 only a small proportion of cognitive genetic research groups reach or break this threshold and even some recent studies still seem content to use sample sizes of a few hundred or less (Bombin et al. 2008; Tsai et al. 2008; Izumi et al. 2008; Schaper et al. 2008; Nacmias et al. 2008). A further emphasis for the need of adequate sample size comes from the GWAS studies of general intelligence (Butcher et al. 2005; Meaburn et al. 2008; Butcher et al. 2008). All of these studies were performed by the same group using an increase in microarray density of 10 k, 100 k and 500 k SNPs. Using a DNA pooling technique on sample of low and high IQ individuals (n = approximately 400 for each group) followed by genotyping of between 4000 and 6000 additional samples the group identified a small number (between 5 and 10) of associated SNPs on each platform. Each SNP only accounted for between 0.15 to 0.2% of the cognitive variance and this magnitude of effect would require a sample number exceeding 4000 to achieve 80% power. The group also created composite SNP sets from the associated SNPs that accounted for between 0.76 and 1% of the variance and which would require smaller numbers for replication (sample sizes of 700 to 800 for 80% power). However, a collaboration of four independent groups (total n = 3539) failed to replicate the 5 SNP set or the composite set results derived from the 10 K platform (Luciano et al. 2008). Hence, we can only conclude that the 10 k microarray/pooling technique may be inadequate to find polymorphisms associated with cognition and that replication of the 100 and 500 k findings is required to confirm the small effect sizes.

Population Stratification

Whilst inadequate statistical power is the most commonly cited cause of non-replication, population stratification effects should also be considered. Unless they are family based, association studies generally require that subjects are from the same population. Variation in disease prevalence, including diabetes, hypertension and dementia, and differences in allele frequencies are common amongst different populations. If analysed together, particularly if the populations are not equally represented throughout the normal distribution, they may distort results leading to a false association, an effect known as population stratification. Although generally, acknowledged as a source of bias, some believe the magnitude of effect is not problematic especially when studying different ethnic groups of non-Hispanic European decent (Wacholder et al. 2002). By contrast, others have shown that even in moderate sample sizes consisting of a few hundred individuals, combinations in disease prevalence and differences in allele frequencies can result in false positive results (Heiman et al. 2004).

Although there are methods for dealing with potential population stratification, including “genomic control,” principal components analysis and “structure methods” (Rodriguez-Murillo and Greenberg 2008) the first step for any study should be the collection of adequate information on ethnic background.

Vascular Risk Factors

Despite age being the main risk factor for cognitive impairment, vascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, smoking, hypercholesterolemia, metabolic syndrome and dyslipidemia have also been shown to play a role in both cognitive decline and dementia (Duron and Hanon 2008). The relative risk for dementia in association with hypertension, obesity, diabetes and dyslipidemia is approximately 1.5 for each factor (Kloppenborg et al. 2008; Whitmer et al. 2007; Gustafson et al. 2003). However, dementia can be considered the end stage of an accumulation of damage and therefore may not be representative of the relative risk caused by vascular factors at much earlier stages of cognitive decline. Indeed, a recent comparison of cross-sectional and longitudinal studies that investigated these four vascular risk factors on cognitive decline in non-demented individuals found variations in effect sizes (van den Berg et al. 2009). Both hypertension (comparison of 24 studies) and diabetes (comparison of 27 studies) were associated with the decline of multiple cognitive abilities over time. However, the association with obesity (comparison of 6 studies) was less clear with domain and age specific effects being reported that were largely inconsistent between studies. Associations with Dyslipidemia (comparison of 7 studies) were equally inconsistent.

Unfortunately, very few cognitive genetic studies have adjusted for vascular risk factors in their analysis even though the evidence suggests that diabetes and hypertension are likely to influence cognitive decline. This information would be particularly relevant to the study of elderly populations where vascular effects are most pronounced.

Summary

Given the wealth of data and lack of total consensus for even a single gene we can assume that either cognitive genetic research has missed the large to moderate effect polymorphisms or that small effect sizes and interactions will predominate. The latter seems an increasingly likely prospect and one which will demand an overhaul of study design, more concentrated funding and the knowledge that gathering detailed environmental data may prove as important as the collection of high quality psychometric and genetic information. At present, the increasing numbers of underpowered and poorly designed studies is making the field difficult to follow, evaluate and interpret and the cost effectiveness of small scale studies is questionable. To ensure optimum use of technology, such as microarrays and the next generation of sequencing, thousands if not tens of thousands of samples will be required, and this will necessitate collaboration and recruitment on a grander scale. The use of principal component analysis and genotype-imputation (Huang et al. 2009b) means that research groups with diverse cognitive measures and genotypes from different microarrays can combine data. These collaborations are beginning to emerge for the study of individual genes (Luciano et al. 2008; Luciano et al. 2009a), and several large cognitive groups in the UK will soon be combining their microarray data for joint analysis. Whether this proves sufficient remains to be seen and a global call for collaboration should be encouraged in order to increase power and provide additional conformation. However, smaller studies will continue to be published and a strategy used by the schizophrenia research community where all studies are recorded on the schizophrenia forum website (www.schizophreniaforum.org) along with the meta-analysis would be an excellent approach for cognitive genetic research groups to follow.

In addition, to the study of SNPs, VNTRs and microsatellites there are other variations both genetic and epigenetic that will begin to appear in the cognitive genetic literature in the near future. Copy Number Variants (CNVs) are large regions of DNA (1 kilobase to several megabases) that can be duplications, insertions, deletions or complex rearrangements which can alter gene function. CNVs have already been associated with several neuropsychiatric conditions including schizophrenia, autism and mental retardation (Cook and Scherer 2008; Kirov et al. 2009; Kumar and Christian 2009). Given their current affect on psychiatric conditions that are associated with a loss of cognitive function it is highly likely that we will see similar associations with cognitive function in cognitively healthy individuals in the near future. Epigenetic regulation of gene expression is another area of potential interest but one that has yet to be explored in the field of cognition. A recent study using a rat model of infant maltreatment showed that early-life adversity altered the methylation patterns of the BDNF gene in the prefrontal cortex of the abused rats which in turn caused a persistent change in BDNF expression (Roth et al. 2009). Changes to methylation patterns were also found to be passed down to the offspring of maltreated women. As discussed earlier, BDNF has been a central focus of cognitive genetic studies and epigenetic modulation of expression of this and other genes may help strengthen future associations. This may entail the gathering of data on stressful life events and the establishment of cognitive brain banks. However, ventures such as this are already underway by projects such as the Research into Ageing funded Dyne Steel cohort for cognitive genetic research which is an ongoing longitudinal study based at the University of Manchester (www.medicine.manchester.ac.uk/genomicepidemiology/research/geneticepidemiology/neurologicalgenetics/behaviouraltraits/cognitiveimpairment/). The point at which variation within a gene has sufficient impact to be realistically useful for diagnosis and treatment for cognitive impairment is still open to speculation. Certainly, nothing approaching a substantial effect size has yet been reported and the conclusion of some scientists that effect sizes under 1% will be the norm does not bode well for future drug development. This, however, assumes that polymorphisms act independently and in my discussion of genes such as BDNF and DRD2 I hope to have dispelled this assumption. As already mentioned genes are fluid entities and their variation in function is rarely due to the effects of a single SNP. Broadening our investigations to include other potential contributing factors that may include CNVs, methylation and environment and then analysing them in combination may tease out those elusive large effects.

Identifying the genetic risk factors for susceptibility to cognitive deficit caused by normal cognitive ageing will be one of a number of important breakthroughs needed to ameliorate cognitive impairment in the elderly. This is a research priority with care costs for those with severe cognitive impairment set to triple in the UK from £5.4 billion in 2002 to £16.7 billion in 2031 in real terms (Comas-Herrera et al. 2007). Whilst there are some tentatively interesting findings in the field of cognitive genetics, there is still clearly a lot of work to do that would benefit from more stringent methodologies, a broadening of the types of variation that gets investigated and the aggregation of current resources.

References

Ahmed, S., Reynolds, B. A., & Weiss, S. (1995). BDNF enhances the differentiation but not the survival of CNS stem cell-derived neuronalprecursors. Journal of Neuroscience, 15, 5765–5778.

Akaboshi, S., Hogema, B. M., Novelletto, A., Malaspina, P., Salomons, G. S., Maropoulos, G. D., et al. (2003). Mutational spectrum of the succinate semialdehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH5A1) gene and functional analysis of 27 novel disease-causing mutations in patients with SSADH deficiency. Human Mutation, 22, 442–450.

Allen, E. G., Sherman, S., Abramowitz, A., Leslie, M., Novak, G., Rusin, M., et al. (2005). Examination of the effect of the polymorphic CGG repeat in the FMR1 gene on cognitive performance. Behavior Genetics, 35, 435–445.

Almeida, O. P., Schwab, S. G., Lautenschlager, N. T., Morar, B., Greenop, K. R., Flicker, L., et al. (2008). KIBRA genetic polymorphism influences episodic memory in later life, but does not increase the risk of mild cognitive impairment. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, 12, 1672–1676.

Antonini, A., Leenders, K. L., Reist, H., Thomann, R., Beer, H. F., & Locher, J. (1993). Effect of age on D2 dopamine receptors in normal human brain measured by positron emission tomography and [11C] raclopride. Archives of Neurology, 50, 474–480.

Bäckman, L., Nyberg, L., Lindenberger, U., Li, S. C., & Farde, L. (2006). The correlative triad among aging, dopamine, and cognition: current status and future prospects. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 30, 791–807.

Ball, D., Hill, L., Eley, T. C., Chorney, M. J., Chorney, K., Thompson, L. A., et al. (1998). Dopamine markers and general cognitive ability. NeuroReport, 9, 347–349.

Bannon, M. J., & Whitty, C. J. (1997). Age-related and regional differences in dopamine mRNA expression in human midbrain. Neurology, 48, 969–977.

Barbaux, S., Plomin, R., & Whitehead, A. S. (2000). Polymorphisms of genes controlling homocysteine/folate metabolism and cognitive function. NeuroReport, 11, 1133–1136.

Barnett, J. H., Scoriels, L., & Munafò, M. R. (2008). Meta-analysis of the cognitive effects of the catechol-O-methyltransferase gene Val158/108Met polymorphism. Biological Psychiatry, 64, 137–144.

Bartrés-Faz, D., Junqué, C., Serra-Grabulosa, J. M., López-Alomar, A., Moya, A., Bargalló, N., et al. (2002). Dopamine DRD2 Taq I polymorphism associates with caudate nucleus volume and cognitive performance in memory impaired subjects. NeuroReport, 13, 1121–1125.

Barzilai, N., Atzmon, G., Derby, C. A., Bauman, J. M., & Lipton, R. B. (2006). A genotype of exceptional longevity is associated with preservation of cognitive function. Neurology, 67, 2170–2175.

Bathum, L., von Bornemann Hjelmborg, J., Christiansen, L., McGue, M., Jeune, B., & Christensen, K. (2007). Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase 677C > T and methionine synthase 2756A > G mutations: no impact on survival, cognitive functioning, or cognitive decline in nonagenarians. Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 62, 196–201.

Batty, G. D., Wennerstad, K. M., Smith, G. D., Gunnell, D., Deary, I. J., & Tynelius, P. (2009). IQ in early adulthood and mortality by middle age: cohort study of 1 million Swedish men. Epidemiology, 20, 100–109.

Baune, B. T., Ponath, G., Rothermundt, M., Riess, O., Funke, H., & Berger, K. (2008). Association between genetic variants of IL-1beta, IL-6 and TNF-alpha cytokines and cognitive performance in the elderly general population of the MEMO-study. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 33, 68–76.

Bendixen, M. H., Nexø, B. A., Bohr, V. A., Frederiksen, H., McGue, M., Kølvraa, S., et al. (2004). A polymorphic marker in the first intron of the Werner gene associates with cognitive function in aged Danish twins. Experimental Gerontology, 39, 1101–1107.

Benson, M. A., Newey, S. E., Martin-Rendon, E., Hawkes, R., & Blake, D. J. (2001). Dysbindin, a novel coiled-coil-containing protein that interacts with the dystrobrevins in muscle and brain. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 276, 24232–24241.

Berman, S. M., & Noble, E. P. (1995). Reduced visuospatial performance in children with the D2 dopamine receptor A1 allele. Behavior Genetics, 25, 45–58.

Blasi, P., Boyl, P. P., Ledda, M., Novelletto, A., Gibson, K. M., Jakobs, C., et al. (2002). Structure of human succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase gene: identification of promoter region and alternatively processed isoforms. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism, 76, 348–362.

Blinkhorn, S. (2005). Intelligence: a gender bender. Nature, 438, 31–32.

Bochdanovits, Z., Gosso, F. M., van den Berg, L., Rizzu, P., Polderman, T. J., Pardo, L. M., et al. (2009). A Functional polymorphism under positive evolutionary selection in ADRB2 is associated with human intelligence with opposite effects in the young and the elderly. Behavior Genetics, 39, 15–23.

Bombin, I., Arango, C., Mayoral, M., Castro-Fornieles, J., Gonzalez-Pinto, A., Gonzalez-Gomez, C., et al. (2008). DRD3, but not COMT or DRD2, genotype affects executive functions in healthy and first-episode psychosis adolescents. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet, 147B, 873–879.