Abstract

Background

The optimal radiotherapy regimen in elderly patients with glioblastoma treated by chemoradiation needs to be addressed. We provide the results of a comparison between conventionally fractionated standard radiotherapy (CRT) and short-course radiotherapy (SRT) in those patients treated by temozolomide-based chemoradiation.

Methods

Patients aged 65 years or older from the GBM-molRPA cohort were included. Patients who were planned for a ≥ 6-week or ≤ 4-week radiotherapy were regarded as being treated by CRT or SRT, respectively. The median RT dose in the CRT and SRT group was 60 Gy in 30 fractions and 45 Gy in 15 fractions, respectively.

Results

A total of 260 and 134 patients aged older than 65 and 70 years were identified, respectively. CRT- and SRT-based chemoradiation was applied for 192 (73.8%) and 68 (26.2%) patients, respectively. Compared to SRT, CRT significantly improved MS from 13.2 to 17.6 months and 13.3 to 16.4 months in patients older than 65 years (P < 0.001) and 70 years (P = 0.002), respectively. Statistical significance remained after adjusting for age, performance status, surgical extent, and MGMT promoter methylation in both age groups. The benefit was clear in all subgroup analyses for patients with Karnofsky performance score 70–100, Karnofsky performance score ≤ 60, gross total resection, biopsy, methylated MGMT promoter, and unmethylated MGMT promoter (all P < 0.05).

Conclusion

CRT significantly improved survival compared to SRT in elderly glioblastoma patients treated with chemoradiation in selected patients amenable for chemoradiation. This study is hypothesis-generating and a prospective randomized trial is urgently warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most frequently diagnosed malignant primary tumor of the central nervous system consisting of nearly 50% [1]. The first-line treatment is temozolomide (TMZ)-based chemoradiation for 6 weeks in those who are presumed to tolerate the therapy, resulting in a dismal median survival below 2 years [2, 3]. However, a majority of GBMs are diagnosed in the elderly with a median age at diagnosis around 65 years [1]. The prognosis of GBM has been known to inversely correlate with increasing age [1,2,3,4], with a reported median survival mostly around 6–12 months for patients older than 65–70 years [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. The standard treatment for these elderly patients with limited survival is highly controversial with recommendations from guidelines varying within a combination of variable radiotherapy (RT) regimens with or without TMZ, or TMZ alone based on clinical and molecular factors [16,17,18,19].

In contrast to the conventionally fractionated standard RT (CRT) of 60 Gy in 30 fractions for 6 weeks, which is recommended in young and well-performing GBM patients under the age of 65 or 70 years, a more abbreviated RT course in 1–4 weeks, the so called short-course RT (SRT) or hypofractionated RT, has been widely investigated among elderly and fragile patients [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. SRT alone, compared to CRT alone, has shown equivalent survival outcomes in randomized trials [5, 7]. Among SRT regimens, even an extremely abbreviated SRT of 25 Gy in 5 fractions has demonstrated similar survival compared to a longer regimen of 40 Gy in 15 fractions [9]. Furthermore, TMZ alone has also shown comparable outcomes in a subset of elderly high-grade astrocytoma patients, mostly GBM, compared to SRT or CRT [7, 8].

Recently, the survival benefit of combining concurrent and adjuvant TMZ with RT was replicated in patients older than 65 years by a Canadian-led phase 3 randomized trial [14]. The absolute survival benefit was modest at 2 months in all patients and was more pronounced in patients with methylation of the O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter [14]. However, all patients in this trial were treated with SRT of 40.5 Gy in 15 fractions, leaving radiation oncologists a question whether SRT is enough in elderly fit patients who are suitable for chemoradiation with good performance status or favorable molecular subtypes.

In our previous studies, a subset of GBM patients with favorable prognostic factors survived exceptionally longer than previous reports following TMZ-based chemoradiation [3, 20]. We assumed that in highly selected elderly patients, a more radical chemoradiation schedule with CRT might provide survival benefit following surgery compared to SRT-based chemoradiation. Therefore, in the multi-institutional cohort from the GBM molecular recursive partitioning analysis (GBM-molRPA) study [3, 20], we performed a hypothesis-generating analysis for patients older than 65 and 70 years focusing on the survival difference based on RT regimens of CRT vs. SRT.

Methods

Patients

This multi-institutional retrospective study was approved by every institutional review boards of participating institutions (Seoul National University Hospital IRB No. 1804–144-941). Korean patients aged 65 years or older were identified from the training and validation set from the 2 published GBM-molRPA studies [3, 20]. Patients who were excluded from the training set due to the lack of information of IDH1 mutation [3], were all reincluded for the current analysis. All patients were newly diagnosed as GBM and underwent TMZ-based concurrent and adjuvant chemoradiation between 2006 and 2016. Gross total resection (GTR) was defined as no evidence of enhancing tumor on postoperative magnetic resonance imaging within 48–72 h. Methylation profiles of the MGMT promoter defined by methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction was available in all patients. More detailed eligibility criteria can be found in our previous reports [3, 20]. Patients who were intended for an abbreviated RT course of 4 weeks or shorter were designated as receiving SRT.

Statistics

The primary endpoint of the study was overall survival, whereas information of progression-survival was not collected. Survival was calculated from the date of surgery or biopsy. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA) was used for analysis. P-value under 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Log-rank test and Cox proportional-hazards model was used for univariate analysis of variables. In the multivariate analysis for survival, the Cox proportional-hazards analysis was performed in a backward-stepwise fashion. For comparison of underlying factors between specific groups, independent T-test or Chi-squared test was used.

Results

Patient characteristics and radiotherapy

A total of 260 and 134 patients aged older than 65 and 70 years were identified, respectively. Detailed patient, tumor, and treatment characteristics of both age groups can be found in Table 1. In the patients aged 65 years or older, 192 (73.8%) and 68 (26.2%) patients were treated by CRT- and SRT-based chemoradiation, respectively. The number of patients treated by CRT- and SRT-based chemoradiation in patients 70 years or older was 83 (61.9%) and 51 (38.1%), respectively.

Among all 260 patients, the median RT dose in the CRT group was 60 Gy in 30 fractions (interquartile dose range, 60–61.2 Gy), whereas the median dose in the SRT group was 45 Gy in 15 fractions (interquartile dose range, 42.5–45 Gy). Only 2 patients (1.0%) in the CRT group actually received an incomplete RT dose lower than 50 Gy (48 Gy in 24 fractions and 41.4 Gy in 23 fractions) due to rapid disease progression during RT, whereas only 1 patient (1.5%) in the SRT group received a dose exceeding 50 Gy (51 Gy in 17 fractions).

A significant selection-bias was observed in choosing the RT schedule (Table 2). Patients treated with CRT were younger (mean age, 69.4 years vs. 74.0 years, P < 0.001), were well-performing (mean Karnofsky performance score, 75.5 vs. 68.4, P = 0.001), and received more GTR (55.1% vs. 37.5%, P < 0.001). However, there was no difference in the proportion of patients with methylated MGMT promoter (CRT 41.3% vs. SRT 48.4%, P = 0.319).

Survival outcome

The median follow-up for survivors were 20.7 and 13.4 months in patients aged older than 65 and 70 years, respectively. The median survival (MS) for each age groups were 16.2 and 15.4 months, respectively. Compared to SRT, CRT significantly improved MS from 13.2 to 17.6 months and 13.3 to 16.4 months in patients older than 65 years (P < 0.001) and 70 years (P = 0.002), respectively. The full results of the univariate analysis for survival in both age groups are listed in Table 1.

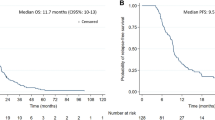

In multivariate analysis (Table 3) for patients with 65 years or older, GTR (P < 0.001), methylated MGMT promoter (P < 0.001), and receiving CRT (P = 0.002) were related with significantly favorable survival outcomes. Age showed marginal significance (P = 0.060) whereas decreased performance status did not affect survival (P = 0.274). In patients aged > 70 years, GTR (P = 0.003) and CRT (P = 0.003) were significantly favorable prognostic factors for survival, whereas MGMT promoter methylation showed marginal significance (P = 0.080). Age (P = 0.320) and performance status (P = 0.173) were not prognostic in patients 70 years or older. In summary, compared to SRT, CRT resulted in significantly better overall survival after adjusting for other variables in both age groups (Fig. 1).

Survival curves of patients older than a 65 years (n = 260) and b 70 years (n = 134) according to radiotherapy regimens. Both survival curves are adjusted for variables included in the multivariate analysis. CRT conventionally fractionated standard radiotherapy, SRT short-course radiotherapy, MS median survival

Since a significant difference in patient characteristics was observed between the CRT and SRT groups, we investigated whether the survival benefit with CRT was valid across all patient subgroups according to performance status, surgical extent, and methylation status of the MGMT promoter in patients older than 65 years. CRT demonstrated significantly improved MS compared to SRT throughout all 6 subgroups as the following: Karnofsky performance score 70–100, Karnofsky performance score ≤ 60, GTR, biopsy, methylated MGMT promoter, and unmethylated MGMT promoter (all P < 0.05) (Table 4, Fig. 2).

Discussion

The standard treatment for GBM in the elderly is highly controversial, and the strategy relies mostly on the institutional or physician’s policy due to the shortness of evidence to date [21]. For example, the most recent version of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guideline provides a wide spectrum of treatment options for patients older than 70 years with good performance and methylated MGMT promoter including CRT + TMZ, SRT + TMZ, TMZ alone, and SRT alone [19]. In contrast, the American Society for Radiation Oncology strongly states that CRT has no benefit over SRT [16]. Although the consensus cut-off for defining ‘elderly’ in this disease has probably narrowed to 70 years or older [16,17,18,19], most of the piled evidence is not based on this cut-off value and used a 60-year or 65-year cut-off for defining the ‘elderly’ [5, 7,8,9, 14]. The definition of ‘elderly or frail’ is currently somewhat ambiguous.

To date, there has been no high-level evidence supporting the superiority of CRT over SRT in elderly patients with GBM when treated by RT alone. Roa et al. have previously shown that SRT of 40 Gy in 15 fractions is equivalent to CRT of 60 Gy in patients aged 60 years older [5]. Furthermore, an even more abbreviated SRT of 25 Gy in 5 fractions was also shown to result in similar survival outcomes compared to the SRT with 40 Gy in patients older than 65 years by Roa et al. [9]. However, both studies were conducted in a very small number of patients [5, 9], the prior study was also underpowered to prove equivalence accruing only half of the targeted accrual number [5], and the latter used a non-standard treatment regimen as the control arm [9]. Moreover, the Nordic study by Malmström et al., where SRT alone of 34 Gy in 10 fractions showed similar efficacy as CRT alone of 60 Gy in patients older than 60 years, more than half of the enrolled patients were younger than 70 years in whom standard chemoradiation should have been the treatment of choice [2, 7]. The selection between CRT and SRT became more complicated since Perry et al. opened the TMZ-based chemoradiation era for GBM in the elderly [14]. Although the benefit of TMZ was only marginal (P = 0.055) at 2 years for patients with unmethylated MGMT [14], the survival gain may become statistically significant as for the patients from the Stupp trial with long-term follow-up [22]. To date, there is no evidence comparing CRT and SRT in the context of concurrent chemoradiation.

In the current study, we have directly compared CRT and SRT in elderly patients treated by TMZ-based chemoradiation and found a significant survival benefit of 3–4 months with CRT compared to SRT. This benefit exceeds that of additional TMZ. Of note, since this study was conducted in patients treated before the benefit of TMZ in elderly was proved by the Canadian-led trial [14], we can assume that highly selected patients who were deemed feasible for chemoradiation as well as CRT by physicians were included. It is reflected in the overall MS of 15–16 months from our study, which is longer than the results of any prospective trial evaluating RT + TMZ in the elderly to date [10,11,12,13,14]. Although there was a significant selection bias between the CRT and SRT groups in terms of age, performance, and surgical extent, the survival superiority of CRT was noted across all subgroups in our study (Table 4, Fig. 2). Moreover, the survival difference remained significant even after adjusting for all clinical factors via multivariate analysis (Table 3).

There are some intuitive hypothetical potentials of CRT that may improve survival compared to SRT. Although GBM is not regarded as a curable disease with chemoradiation, administration of RT prolongs progression-free survival, as it does for low-grade diffuse gliomas [6, 23]. Since almost all patients with GBM die due to the disease itself [24], it is important to delay progression, and most GBM patients recur locally at first progression. Therefore, local delivery of higher RT dose, especially when combined with the radiosensitizing TMZ, might play a role in delaying progression. Assuming a tumor α/β ratio of 9 Gy [25], CRT of 60 Gy in 30 fractions results in a higher biologically effective dose of 73 Gy compared to that of 52 Gy in patients treated with the most widely used SRT of 40 Gy in 15 fractions. Indeed, even in patients undergoing biopsy, in which large tumor burden would reside, CRT significantly prolonged MS by 8 months. However, since the biologically effective dose is also higher for the normal brain tissue with CRT, careful selection of elderly patients who can tolerate the 6-week course of CRT without deterioration of performance or worsening of general medical conditions would be critical.

This study has some limitations including its retrospective nature and the lack of information of the selection criteria for administrating chemoradiation in the elderly. Hence, the results of this study are only applicable for highly selected patients without a known selection criterion. CRT will not be as cost-effective for all elderly patients, especially in elderly patients who would survive only 6–8 months [5,6,7,8,9]. Unfortunately, we do not have any predictive tools to gain clue on which RT schedule would be more appropriate in an individual basis. However, as the life expectancy keep increasing especially in developed countries [26], patients older than 65 years or 70 years might not be as fragile as in the past, requiring a more radical chemoradiation regimen as in younger patients rather than a palliative approach.

In summary, CRT significantly prolonged overall survival compared to SRT in selected elderly GBM patients treated with TMZ-based chemoradiation in this largest dataset to date. The survival benefit was valid in all prognostic subgroups. Of note, the findings of this study are only hypothesis-generating, raising the urgency for high-level evidence comparing CRT- and SRT-based chemoradiation for elderly GBM patients. The selection criteria should be investigated as well.

Change history

12 May 2020

The name of author Do Hoon Lim was incorrect in the initial online publication. The original article has been corrected.

Abbreviations

- GMB:

-

Glioblastoma

- TMZ:

-

Temozolomide

- RT:

-

Radiotherapy

- CRT:

-

Conventionally fractionated standard radiotherapy

- SRT:

-

Short-course radiotherapy

- MGMT :

-

O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase

- GBM-molRPA:

-

Glioblastoma molecular recursive partitioning analysis

- GTR:

-

Gross total resection

- MS:

-

Median survival

References

Ostrom QT, Cioffi G, Gittleman H et al (2019) CBTRUS statistical report: primary Brain and other Central Nervous System Tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2012–2016. Neuro Oncol 21(5):51–5100

Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ et al (2005) Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 352(10):987–996

Wee CW, Kim E, Kim N et al (2017) Novel recursive partitioning analysis classification for newly diagnosed glioblastoma: A multi-institutional study highlighting the MGMT promoter methylation and IDH1 gene mutation status. Radiother Oncol 123(1):106–111

Paszat L, Laperriere N, Groome P, Schulze K, Mackillop W, Holowaty E (2001) A population-based study of glioblastoma multiforme. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 51(1):100–107

Roa W, Brasher PM, Bauman G et al (2004) Abbreviated course of radiation therapy in older patients with glioblastoma multiforme: a prospective randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 22(9):1583–1588

Keime-Guibert F, Chinot O, Taillandier L et al (2007) Radiotherapy for glioblastoma in the elderly. N Engl J Med 356(15):1527–1535

Malmström A, Grønberg BH, Marosi C et al (2012) Temozolomide versus standard 6-week radiotherapy versus hypofractionated radiotherapy in patients older than 60 years with glioblastoma: the Nordic randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 13(9):916–926

Wick W, Platten M, Meisner C et al (2012) Temozolomide chemotherapy alone versus radiotherapy alone for malignant astrocytoma in the elderly: the NOA-08 randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 13(7):707–715

Roa W, Kepka L, Kumar N et al (2015) International Atomic Energy Agency randomized phase III study of radiation therapy in elderly and/or frail patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme. J Clin Oncol 33(35):4145–4150

Minniti G, De Sanctis V, Muni R et al (2008) Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma in elderly patients. J Neurooncol 88(1):97–103

Minniti G, De Sanctis V, Muni R et al (2009) Hypofractionated radiotherapy followed by adjuvant chemotherapy with temozolomide in elderly patients with glioblastoma. J Neurooncol 91(1):95–100

Brandes AA, Franceschi E, Tosoni A et al (2009) Temozolomide concomitant and adjuvant to radiotherapy in elderly patients with glioblastoma: correlation with MGMT promoter methylation status. Cancer 115(15):3512–3518

Minniti G, Lanzetta G, Scaringi C et al (2012) Phase II study of short-course radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide in elderly patients with glioblastoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 83(1):93–99

Perry JR, Laperriere N, O'Callaghan CJ et al (2017) Short-course radiation plus temozolomide in elderly patients with glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 376(11):1027–1037

Arvold ND, Tanguturi SK, Aizer AA et al (2015) Hypofractionated versus standard radiation therapy with or without temozolomide for older glioblastoma patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 92(2):384–389

Cabrera AR, Kirkpatrick JP, Fiveash JB et al (2016) Radiation therapy for glioblastoma: executive summary of an American Society for Radiation Oncology evidence-based clinical practice guideline. Pract Radiat Oncol 6(4):217–225

Weller M, van den Bent M, Tonn JC et al (2017) European Association for Neuro-Oncology (EANO) guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of adult astrocytic and oligodendroglial gliomas. Lancet Oncol 18(6):e315–e329

Kim YZ, Kim CY, Lim J et al (2019) The Korean Society for Neuro-oncology (KSNO) guideline for glioblastomas: version 2018.01. Brain Tumor Res Treat 7(1):1–9

National Comprehensive Cancer Network clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Central nervous system cancers, Version 3.2019. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cns.pdf. Accessed 26 Nov 2019.

Wee CW, Kim IH, Park CK et al (2018) Validation of a novel molecular RPA classification in glioblastoma (GBM-molRPA) treated with chemoradiation: a multi-institutional collaborative study. Radiother Oncol 129(2):347–351

Lim YJ, Kim IH, Han TJ et al (2015) Hypofractionated chemoradiotherapy with temozolomide as a treatment option for glioblastoma patients with poor prognostic features. Int J Clin Oncol 20(1):21–28

Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP et al (2009) Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol 10(5):459–466

van den Bent MJ, Afra D, de Witte O et al (2005) Long-term efficacy of early versus delayed radiotherapy for low-grade astrocytoma and oligodendroglioma in adults: the EORTC 22845 randomised trial. Lancet 366(9490):985–990

Best B, Nguyen HS, Doan NB et al (2019) Causes of death in glioblastoma: insights from the SEER database. J Neurosurg Sci 63(2):121–126

Jones B, Sanghera P (2007) Estimation of radiobiologic parameters and equivalent radiation dose of cytotoxic chemotherapy in malignant glioma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 68(2):441–448

Global Health Observatory data repository. https://apps.who.int/gho/data/view.main.60000?lang=en. Accessed 26 Nov 2019.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by every institutional review boards of participating institutions (Seoul National University Hospital IRB No. 1804-144-941). For this type of study formal consent is not required.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article has been revised: The seventh author’s name has been corrected.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wee, C.W., Kim, I.H., Park, CK. et al. Chemoradiation in elderly patients with glioblastoma from the multi-institutional GBM-molRPA cohort: is short-course radiotherapy enough or is it a matter of selection?. J Neurooncol 148, 57–65 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-020-03468-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-020-03468-x