Abstract

Purpose

Chondroblastoma (CB) in the spine is extremely rare and there is little published information regarding this subject. We attempt to explore the clinical features of spinal CB and address the importance of total resection, especially total en bloc spondylectomy (TES) for the treatment of spinal CB.

Methods

Clinical data of 13 consecutive CB patients who received surgical treatment in our center between January 2006 and December 2016 were reviewed retrospectively. Recurrence-free survival (RFS) was estimated by Kaplan–Meier method and Log-rank test.

Results

The 13 CB patients included 9 men and 4 women with a mean age of 32 years. The lesions were located in the cervical spine in 2 cases, thoracic spine in 5 cases, and lumbar spine in 6 cases. All the patients were treated surgically using either curettage, piecemeal total resection, or TES. Postoperative radiotherapy was administered in 2 cases. The mean follow-up period was 41.6 months. Relapse occurred in 3 (23.1%) cases, resulting in one death in 60 months. The mean RFS duration was 28.7 months.

Conclusions

CB predominantly affects males and various age groups. Spinal CB more commonly involves the thoracic and lumbar segments. Spinal CB usually appears as an aggressive and destructive bony lesion with a soft tissue mass on imaging, forming compression on the spinal cord in some cases. Recurrence is not uncommon for spinal CB. Total resection, especially TES, has been confirmed as a powerful method to control the disease, while curettage is more likely to associate with local recurrence. Radiotherapy does not seem to reduce local recurrence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Chondroblastoma (CB) is a rare chondrogenic bone tumor accounting for about 1–1.45% of all primary bone tumors [1,2,3,4,5]. CB usually affects the epiphyses of long bones with a peak occurrence in the second decade of life [4, 6, 7]. The distal femur is the most common location to be affected by CB, and the spine is rarely affected, accounting for about 1.4% of all CB cases [3, 4]. Only about 30 cases of spinal CB have been published, mostly as case reports [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. Ilaslan et al. [4] reported 9 spinal CB cases but did not provide useful information about the treatment of the disease.

According to the latest World Health Organization (WHO) classification [1, 25], CB is categorized as a locally aggressive, rarely metastasizing (< 2%) intermediate tumor instead of a benign lesion. The local recurrence rate is reported to be as high as 38%, and pulmonary metastasis can occur in 2% [1, 3, 5, 7]. CB occurring in the spine seems to be more aggressive and expansive than that occurring in long bones, because the lesion usually involves both the anterior and posterior aspects of the vertebrae [2, 5, 19]. As CB was previously seen as a benign tumor, curettage or debulking surgery has long been the mainstay of treatment for spinal CB [11, 14, 19,20,21,22], but it often leads to high local recurrences. According to the report by Ilaslan et al. [4], 5 of their 7 patients experienced recurrences (including two deaths) within 12 months of treatment, indicating the poor prognosis of spinal CB. Total en bloc spondylectomy (TES), which is designed to achieve complete resection of malignant tumors, was rarely used in the treatment of spinal CB because of the “intermediate” nature of the tumor and complexity of the spinal anatomies. The possible epidemiological and therapeutic features of spinal CB are not clear because of the lack of information reported in previous individual case reports [4]. The aim of this retrospective study was to identify the clinical features of spinal CB and emphasize the importance of total resection, especially TES, in the treatment of spinal CB by summarizing the clinical data of 13 consecutive patients treated in our center.

Patients and methods

Upon approval from the ethics committee of the hospital, we retrospectively studied 13 patients who were histologically confirmed as having CB and received surgical treatment in our hospital between January 2006 and December 2016. The diagnosis was confirmed by two experienced neuro-pathologists independently. Data were collected by reviewing the medical records, radiographs and pathologic reports. Informed consent was obtained from the surviving patients or family members of those who had passed away.

The pre- and post-operative neurologic status was evaluated according to the Frankel score [26]. All patients received at least one operation in our center through individualized approaches according to the Weinstein-Boriani-Biagini (WBB) system [27] and Tomita classification [28]. The screw-rod system with or without the titanium mesh was used to reconstruct stability of the spine in all patients. Local recurrence or death was recorded. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 21.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The recurrence-free survival (RFS) rate was estimated by the Kaplan–Meier survival curve and Log-rank test. p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Chest plain X-ray radiography was performed to see whether there was lung metastasis during the follow-up period. Regular assessments were performed at 3, 6 and 12 months after surgery, every 6 months for the next 2 years, and then annually. Follow-up data were obtained from office visits and telephone interviews. The follow-up period was defined as the interval from the date of surgery to death, or until March 2018 for patients alive.

Results

Patient features

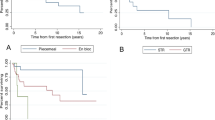

The basic clinical data of the patients is summarized in Table 1. Our series comprised 9 men and 4 women, who ranged in age from 16 to 60 years with a mean of 32.0 and a median of 26 years. Among these patients, 6 (46.2%) patients were older than 30 years (Fig. 1a). The lesions were located in the cervical (n = 2), thoracic (n = 5) and lumbar spine (n = 6). CB involved one segment in 10 patients, and 2 or 3 segments in 3 patients. The clinical manifestations were usually non-specific, with localized pain in the spine as the most common complaint, lasting a mean of 7.9 months (median 8; range 1–16). Additional symptoms included varying degrees of cord compression at the time of diagnosis in 9 (65%) patients with the Frankel score ranging from C to D. Two thoracic lesions presented as a palpable mass in Case 4 and 7. Three patients developed secondary aneurysmal bone cysts (ABC).

The mean follow-up period was 41.6 months (median 39; range 24–72), and recurrence occurred in 3 patients (23.1%) with a mean RFS duration of 28.7 (median 20; range 18–48) months. Of the 3 patients, one passed away 60 months after surgery during the follow-up period.

Treatment history

Only one patient came to our center for the recurrent lesion and intractable local pain. This patient had already received curettage of T2 at another institution, where the pathological diagnosis was CB. Unfortunately, the tumor recurred quickly and also invaded the adjacent segments 6 months later (Fig. 2).

A 26-year-old man (case 8) a Compression fracture and matrix calcification occurred before the first surgery in CT. b Postoperative X-ray showed decompression and instrumentation. c CT images showed the recurrence of the lesion at T1-3. d MRI showed the relapse and spinal canal invasion. e Specimen of the recurred lesion. f Plain X-ray of the specimen. g Secondary postoperative X-ray showed sound reconstruction by anterior titanium mesh and posterior screw-rod system

Radiologic study

Lesion extension was described according to the WBB system, Enneking stage and Tomota classification system, based on CT and MR images. According to the WBB system, associated anterior (5–8 section) and posterior (1–4, 9–12 section) involvement was seen in 12 patients, while anterior involvement occurred in one patient. Extra-osseous paravertebral (layer A) or epidural space (layer D) invasion was detected in 12 and 9 cases of our series respectively. In imaging study of MRI or CT, care should be taken to differentiate spinal CB from solitary myeloma, giant cell tumor (GCT) or aggressive osteoblastoma. In the 5 cases of spinal CB affecting the thoracic segments, the costotransverse joint was involved in 4, and some part of the posterior rib was also involved in 2. Compression fracture was uncommon in our series, occurring in 2 (15.4%) of the 13 cases. Matrix calcifications were detected in 6 cases (46.2%) by CT scan. Secondary ABC was detected in 3 patients (Case 1, 9 and 12). A heterogeneous enhancement after the administration of a contrast medium was common in MRI images.

Treatment and outcomes

Preoperative CT-guided bone biopsy and intraoperative fast pathologic examination were performed in 11 and 2 patients, respectively. However, 4 lesions were pathologically misdiagnosed as giant-cell tumors. Selective arterial embolization was used through digital subtraction arteriography (DSA) 24 h before surgery in 5 patients whose lesions showed clear bleeding vessels on CTA images. For 2 cervical lesions, one-stage posterior and anterior approach surgery was conducted, while the single posterior approach was applied in the other 11 patients.

According to the WBB system and Tomita classification, individualized surgery was planned and three different resection methods including TES, piecemeal total resection and curettage were implemented. TES (3 marginal margins and 2 wide margins) was performed in 5 patients, whose lesions showed well-defined reactive membranes. Six patients received piecemeal total resection to remove the bone lesions to the maximum extent assisted with local chemotherapy. For the recurrent patient (Case 8), seeing that the adjacent vertebrae and the surrounding soft tissue were extensively invaded (Fig. 2c, d), piecemeal total resection was applied to remove the lesion to the largest degree (Fig. 2e, f). Curettage, assisted with adjuvant radiotherapy, was conducted in 2 patients and the result was unsatisfied in that both showed recurrence within 2 years. Intraoperative blood loss ranged from 1100 to 6500 (mean 3030) ml.

The local pain symptom resolved or disappeared in all patients after surgical treatment. The neurological status at 3-month follow-up showed the improvement of Frankel score by 1–2 grades in 8 patients. However, the function of the lower extremities was decreased in Case 4 due to ischemical reperfusion injury (IRI). The treatment modalities and outcomes are listed in Table 2. For patients receiving TES treatment, no recurrence occurred during the mean follow-up duration of 32 months. Recurrence occurred in one (16.7%) of the 6 patients receiving piecemeal total resection 48 months after surgery. To better understand the outcomes of different surgical methods, we conducted Kaplan–Meier survival curve and Log-rank test and the result showed p value = 0.001 (Fig. 1b). No metastasis was observed during the follow-up period in our series.

Pathology

In patients receiving TES, all cutting margins (gross normal surrounding tissue) were submitted for pathologic examination and 3 of 5 showed marginal margins. Histological diagnosis was obtained in all cases. Randomly distributed osteoclast-like giant cells were present in 10 of the 13 cases. Mitotic figures are rare (about 1–3 mitoses per 10 high-power fields) in 6 cases. Immunochemical study showed that the lesions were mostly positive for Vimentin (12), S-100 (9), CD68 (9), AAT (4) and AACT (5), and negative for P53 (8), CK8 (4), and CK (pan) (4). P63 was positive in 6 cases and negative in the other 7 cases. Ki-67 was commonly positive with a range of 2–15%.

Complications

Pleural damage occurred in Case 7and 8, in which pleurocentesis and drainage were conducted to alleviate the post-operative pleural effusion. The patient in Case 4 suffered from IRI, whose neurologic function worsened postoperatively and recovered gradually within a year. He is now still living normally. Severe bleeding (> 3000 ml) occurred in 5 cases and recovered gradually after blood transfusion and use of erythropoietin.

Discussion

In the recent WHO classification, CB is categorized as a locally aggressive and rarely metastatic tumor [1, 25]. When compared with other aggressive vertebral lesions such as GCT (13%), ABC (14%) and osteoblastoma (37%), CB accounts for only 1% of all primary bone tumors [4, 29]. Because of the low incidence of spinal CB (1.4%), there is not much research on it and therefore there lacks evidence-based treatment information. As a result, there is no consensus opinion about the treatment of this disease, which is one of the reasons for unnecessary mortality and morbidity. Previous reports [3,4,5] showed that the mean local relapse rate was high as 33.3%, rendering it a clinical challenge in front of spinal surgeons. The aim of the present study was to shed more light on the clinical features and treatment of spinal CB by summarizing the data of 13 consecutive patients with a minimal follow-up period of 2 years in a single center in China.

We found that male individuals were more commonly affected by spinal CB than females with a M/F ratio of 9:4, which is similar to other reports [1, 2, 4, 30]. Previous studies [5, 7,8,9,10,11] showed spinal CB was usually located in the cervical spine and rarely involved the lumbar and sacral segments. However, our study showed the lumbar and thoracic segments were more commonly affected, occurring in 6 and 5 cases in our series respectively, and cervical invasion occurred in only one case. The 13 spinal CB cases in our series covered a wide range of age, with 6 (46.2%) patients older than 30 years, which is inconsistent with the general recognition that CB mainly affects young people in the second decade of life [1, 2, 25, 30, 31]. Most of our patients (12/13) reported mild localized pain, which is consistent with most published reports [3,4,5, 8,9,10]. As spinal CB seems more aggressive and expansive [2, 5, 19], soft tissue masses and epidural space (layer D) involvement are common. Two patients in our series had a palpable mass near the lesion.

As spinal CB typically appears as an aggressive osteolytic lesion, it is sometimes difficult to differentiate it from other aggressive or malignant tumors [2, 5, 19]. CT scan is superior to X-ray radiography in evaluating bone destruction, and contrast-enhanced MRI is more accurate in detecting soft-tissue extension and spinal canal invasion. In line with previous reports [5, 19], most spinal lesions in our series invaded the anterior and posterior column (12/13) with no isolated posterior localization. As CB has a predilection for the epiphysis of the growing skeleton [1,2,3], the lesion may originate from the superior facet, inferior facet or costotransverse joint which are considered during growth and then extend to the anterior column, posterior column, intra-spinal canal and even posterior costal segments. As a result, tumors are inclined to destruct one side of the vertebrae [3, 5, 22]. The pathologic compression fractures are rare in spinal CB cases [3, 4, 7, 8].

The mitotic figure, ranging from 1 to 3/10 HPF, was observed in some cases, which is consistent with other reports [1]. The main differential diagnosis of spinal CB is GCT. P63 is proposed to be a sensitive (96.8%) and relatively specific marker for discriminating GCT from other types of giant cell-rich lesions [32]. In our cases, only 6 patients showed weak positive P63. Meanwhile, Shilpa et al. [33] also illustrated the different features of mononuclear cells of the two tumors, which should help make a right diagnosis.

Surgical resection is the mainstay of treatment for CB of all locations [1, 4, 7]. Although 80–90% CB cases have been successfully treated by simple curettage, especially for appendicular CB, it is difficult to control spinal CB successfully [1, 3, 31]. One patient (Case 8) in our series had been treated by simple curettage in another hospital. Although his intractable pain was relieved after surgery, MRI detected recurrence of the lesion in the original segment and invasion of lesion to the adjacent vertebra with a soft tissue mass detected 6 months after curettage. In such a case, surgical re-resection and reconstruction of the spine are more difficult. As it was unfeasible to conduct TES, we performed piecemeal total resection in this patient and the prognosis was satisfied with no disease progression again. In addition, 2 patients treated by curettage showed tumor progression within 2 years. Our log-rank test and Kaplan–Meier curve analysis showed significant differences between the three treatment methods (p = 0.001). TES is originally designed for radical resection of malignant tumors. As spinal CB usually shows an aggressive feature instead of a benign one, it is of great significance to conduct TES when possible. No recurrence occurred in TES group of our series. Although piecemeal total resection has the possibility of tumor cell contamination in the surgical field [28] and the filtration feature of spinal CBs [1, 16], we found that it could significantly reduce the recurrence rate of spinal CB when compared with subtotal resection plus radiotherapy, for only one patient in our series experienced recurrence 48 months after the initial operation.

The efficacy of radiotherapy for spinal CB remains controversial. Some researchers warmed that radiotherapy may induce post-radiation sarcoma [34], while others argued that it was an effective adjuvant therapy when total excision was not possible [14, 15, 22]. Our study showed that subtotal resection plus postoperative radiotherapy resulted in a high recurrence rate, which seemingly suggests that radiotherapy does not seem to reduce local recurrence.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest cohort study on spinal CB with a long-term follow-up period. However, the relatively low absolute number of events made it impossible to perform extensive statistical analyses. In addition, the retrospective nature of the study may also affect the heterogeneity of the follow-up data and conclusion drawn from the study.

Conclusion

Chondroblastoma predominantly affects males and various age groups when it occurs in the spine. The thoracic and lumbar segments are more commonly involved than the cervical spine. On imaging, it usually appears as an aggressive and destructive bony lesion with a soft tissue mass, causing significant compression on the spinal cord in some cases. Recurrence is not uncommon in spinal CB. Total resection, especially TES, has been confirmed to be a powerful method to control the disease, and curettage is more likely to result in recurrence. Radiotherapy does not seem to reduce local recurrence.

References

Konishi E, Nakashima Y, Mano M et al (2017) Chondroblastoma of extra-craniofacial bones: clinicopathological analyses of 103 cases. Pathol Int 67:495–502

Bloem JL, Mulder JD (1985) Chondroblastoma: a clinical and radiological study of 104 cases. Skeletal Radiol 14:1–9

Venkatasamy A. Chenard MP, Massard G et al (2017) Chondroblastoma of the thoracic spine: a rare location: case report with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Skeletal Radiol 46:367–372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00256-016-2550-0

Ilaslan H, Sundaram M, Unni KK (2003) Vertebral chondroblastoma. Skeletal Radiol 32:66–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00256-002-0599-4

Vialle R, Feydy A, Rillardon L et al (2005) Chondroblastoma of the lumbar spine: report of two cases and review of the literature. J Neurosurg 2:596–600

Kurt AM, Unni KK, Sim FH et al (1989) Chondroblastoma of bone. Hum Pathol 20:965–976

Sohn SH, Koh SA, Kim DG et al (2009) A case of spine origin chondroblastoma metastasis to lung. Cancer Res Treat 41(4):241–244. https://doi.org/10.4143/crt.2009.41.4.241

Osman W, Zaoui A, Soumaya BA et al (2014) Chondroblastoma of the lower thoracic spine: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Med Case Rep 2(4):78–81

Ehalt W, Ratzenhofer M (1967) Zur Kasuistik des Gutartigen Chondroblastomes. Z Orthop 102(4):625–629

Wigwicki T (1969) Dziaka: cshondroblastoma. WIAD LA 22(15):1387–1392

Wisniewski M, Toker C, Anderson PJ et al (1973) Chondroblastoma of the cervical spine: case report. J Neurosurg 38(6):763–766

Brasse F, Hoeffel JC, Montaut J et al (1985) A proposd’un chrondroblastome vertebral. Rev Chir Orthop 71(6):389–392

Edel G, Ueda Y, Nakanishi J et al (1992) Chondroblastoma of bone: a clinical, radiological, light and immunohistochemical study. Virchows Arch A 421(4):355–366

Akai M, Tateishi A, Machinami R et al (1986) Chondroblastoma of the sacrum: case report. Acta Orthop Scand 57(4):378–381

Hoeffel JC, Brasse F, Schmitt M et al (1987) About one case of vertebral chondroblastoma. Pediatr Radiol 17(5):392–396

Howe JW, Baumgard S, Jochum TR et al (1988) Case report 449: chondroblastoma involving C5 and C6. Skelet Radiol 17(1):52–55

Kurth AA, Warzecha J, Rittmeister M et al (2000) Recurrent chondroblastoma of the upper thoracic spine: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 120(9):544–557

Attar A, Ugur HC, Caglar YS et al (2001) Chondroblastoma of the thoracic vertebra. J Clin Neurosci 8(1):59–60

Leung LY, Shu SJ, Chan MK et al (2001) Chondroblastoma of the lumbar vertebra. Skelet Radiol 30(12):710–713

Shin BJ, Yun TK, Lim KC et al (2001) Chondroblastoma of the first lumbar vertebra: a case report. J Korean Soc Spine Surg 8:90–95

Nishida J, Kato S, Murakami H et al (2003) Tetraparesis caused by chondroblastoma of the cervical spine: a case report. Spine, 28(9), E173–E178

Chung OM, Yip SF, Ngan KC et al (2003) Chondroblastoma of the lumbar spine with cauda equina syndrome. Spinal Cord 41:359–364

Lee YH, Shin DA, Kim KN et al (2005) A case of thoracic vertebral chondroblastoma, treated with 3-D image resection and reconstruction. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 37, 154–156

Kim SA, Cho KJ, Park YK et al (2011) Chondroblastoma of the lumbar spine: a case report and review of the literature. Korean J Pathol 45:532–536

Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn et al (2011) WHO classification of tumours of soft tissue and bone. 4th edn. Lyon: IARC

Frankel HL, Hancock DO, Hyslop G et al (1969) The value of postural reduction in the initial management of closed injuries of the spine with paraplegia and tetraplegia: I. Paraplegia 7(3):179–192

Boriani S, Weinstein JN, Biagini R (1997) Primary bone tumors of the spine: terminology and surgical staging. Spine 22(9):1036–1044

Tomita K, Kawahara N, Murakami H et al (2006) Total en bloc spondylectomy for spinal tumors: improvement of the technique and its associated basic background. J Orthop Sci 11(1):3–12

Unni KK (ed) (1996) Dahlin’s textbook of bone tumors, 5th edn. Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia/New York

Suneja R, Grimer RJ, Belthur M et al (2005) Chondroblastoma of bone: long-term results and functional outcome after intralesional curettage. J Bone Joint Surg Br 87:974–978

Lin PP, Thenappan A, Deavers MT et al (2005) Treatment and prognosis of chondroblastoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res 438:103–109

Shooshtarizadeh T, Rahimi M, Movahedinia S (2016) P63 expression as a biomarker discriminating giant cell tumor of bone from other giant cell-rich bone lesions. Pathology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prp.2016.07.007

Tathe SP, Parate SN, Jaiswal KN et al (2018) Intraoperative crush smear cytology of vertebral chondroblastoma: a diagnostic challenge. Diagn Cytopathol 46:79–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/dc.23799

Angelini A, Hassani M, Andreas F et al (2017) Mavrogenis: chondroblastoma in adult age. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 27:843–849. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00590-017-1996-7

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No benefits in any form have been or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this manuscript. No conflict of interest exists in the submission of this manuscript for all authors, and manuscript is approved by all authors for publication

Funding

This work was supported by Grants from National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFC0902100).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jia, Q., Liu, C., Yang, J. et al. Clinical features, treatments and long-term follow-up outcomes of spinal chondroblastoma: report of 13 clinical cases in a single center. J Neurooncol 140, 99–106 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-018-2935-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-018-2935-0