Abstract

The EORTC/NCIC 22981/26981 study demonstrated an improvement in median overall survival (OS) from 12.1 to 14.6 months in patients with glioblastoma (GBM) who received temozolomide with post-operative radiotherapy (RT). The current study was performed to determine if those results translated into a survival benefit in a population-based cohort. Patients diagnosed between 2000 and 2006 with a GBM who underwent surgery and post-operative RT were selected from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results database. Patients were grouped into time periods: 2000–2001, 2002–2003, 2004 and 2005–2006 (which represented those treated after the EORTC/NCIC trial presentation in 2004). Relative survival (RS) was estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method, and Cox multivariable regression modeling was used to estimate proportional hazard ratios (HR). Over time, there was improvement in the median and 2-year RS of 12 months and 15% for 2000–2001, 13 months and 19% for 2002–2003, 14 months and 24% for 2004, and 15 months and 26% for 2005–2006 (P < 0.0001 compared to 2000–2001 and 2002–2003; P = 0.07 compared to 2004). The estimated adjusted HR showed that patients diagnosed in 2005–2006 had significantly improved survival when compared to patients diagnosed in 2000–2001 (HR = 0.648, 95% CI 0.604–0.696). The median and 2 year RS of 15 months and 26% in 2005–2006 was similar to the median and 2 year OS of 14.6 months and 26% seen in the EORTC/NCIC phase III study. These results are encouraging and suggest that the current treatment of glioblastoma nationwide is now associated with an improved survival compared to previous time cohorts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Glioblastoma (GBM) is associated with a poor prognosis [1–5]. Historically, treatment included surgical resection followed by post-operative radiation therapy which was associated with a small survival benefit [6].

A practice changing phase III study by the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) group and National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group (NCIC) established the current treatment regimen when it was presented in 2004 [7, 8]. This study randomized patients to post-operative radiation therapy versus post-operative radiation therapy with concurrent temozolomide followed by six cycles of adjuvant temozolomide. Initially, it revealed a significant improvement in 2 year overall survival from 10.4% with post-operative radiotherapy alone to 26.5% with post-operative radiotherapy plus temozolomide. After a median follow up of 5 years these results persisted and the temozolomide plus post-operative radiotherapy arm was associated with a hazard ratio of 0.63 (95% CI 0.53–0.75) when compared to patients who received post-operative radiotherapy alone [9, 10].

We undertook the current study to determine if the results of the EORTC/NCIC phase III trial translated to a nationwide improvement in overall survival in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Using a large population-based cohort, we examined if patients diagnosed after the EORTC/NCIC phase III study reporting had outcomes similar to those treated on the post-operative radiation therapy plus temozolomide arm of the study.

Methods

Data and study population

The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database of the National Cancer Institute covers 26% of the US population and collects incidence and survival data from 17 population-based cancer registries [11]. The database contains information on primary tumor site, age, gender, histology, stage at diagnosis, first course of treatment, and overall survival. Patients selected for inclusion in this study were aged 20 years and older and had a microscopically-confirmed first primary of glioblastoma (International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Version 3 histology codes 9440–9442) diagnosed during 2000–2006. All selected patients underwent either surgical resection or biopsy followed by post-operative radiation therapy and were followed for a minimum of one year. Of 15,546 glioblastomas diagnosed in 2000–2006 in those aged 20 years and older, exclusions were performed for 2,127 second or later primaries, 86 autopsy only, 1,172 non-microscopically confirmed cases, 55 cases not included in the research database, and 13 cases alive with no survival time. In addition, 5,071 glioblastomas were excluded because they received a treatment regimen other than surgery followed by post-operative radiation therapy. One hundred three glioblastomas were excluded because the type of surgery was unknown (n = 76), or only local tumor destruction was performed (n = 27). The final sample size included 6,919 patients.

Patients were grouped into time periods for comparison: 2000–2001, 2002–2003, 2004, and 2005–2006 (which represented the group treated after the EORTC/NCIC trial initial presentation in the middle of 2004). Survival time was defined as the time from diagnosis to the date of death from any cause or the date of last known follow-up. The extent of surgery was determined from the operative note and, for these analyses; this variable was grouped into sub-total resection, which included patients who underwent a biopsy, or gross total resection. Covariates in the statistical analysis included extent of surgery, age group at diagnosis (20–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, 75+ yr), sex, race (white, black, other), Hispanic ethnicity, and SEER registry. Information regarding the utilization of chemotherapy, local control, performance status, and specific radiation therapy technique (including dose, fractionation, beam energy) is not available on the SEER research database.

Statistical analysis

Estimates of relative survival (RS), the ratio of observed survival to the expected survival rate were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method. All statistical tests were two-sided, and significance was defined as P < 0.05. The log rank test was used to estimate whether there were differences in RS based on the year diagnosed. To further examine the association between post-operative radiation therapy and survival, hazard ratios (HR) and the corresponding 95% confidence limits (CL) were estimated using Cox proportional hazards regression models including multivariable models for all estimates adjusted for all covariates [12]. Kaplan–Meier survival analyses were conducted using SEER*Stat version 7.0.4 [13]. Proportional hazards regression analyses were performed using PASW Statistics 18, Release Version 18.0.0 (SPSS Inc., 2009, Chicago, IL, www.spss.com).

Results

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Among the 6,919 patients, 25.7% were diagnosed during 2001–2001, 28.3% were diagnosed during 2002–2003, 15.8% were diagnosed in 2004, and 30.3% were diagnosed during 2005–2006. The median follow-up was 12 months. The median age of patients diagnosed in the study was 59 years. Approximately 80% of patients were recorded as having undergone a gross total resection.

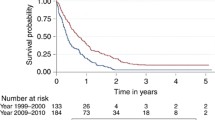

The median and two year RS for the entire cohort was 13 months and 20%, respectively. Over the time periods studied, there was a significant improvement in the median and 2 year RS of 12 months and 15% for 2000–2001, 13 months and 19% for 2002–2003, 14 months and 24% for 2004, and 15 months and 26% for 2005–2006 (P < 0.0001 compared to 2000–2001 and 2002–2003; P = 0.07 compared to 2004) (Fig. 1). When restricted to those aged 20–69 years, the same patterns with slightly better survival were found with 2 year RS of 18% for 2000–2001, 22% for 2002–2003, 28% for 2004, and 30% for 2005–2006 (P < 0.0001 compared to 2000–2001 and 2002–2003; P = 0.18 compared to 2004).

After adjusting for known patient characteristics, the estimated adjusted hazard ratio showed that patients diagnosed in 2005–2006 had significantly improved survival when compared to patients diagnosed in earlier time periods (HR = 0.648, 95% CI 0.604–0.696) (Table 2). Race, ethnicity, and extent of resection were not significant on multivariate analysis. Registry location was significant on multivariate analysis. As expected, increasing age was associated with an increasing hazard ratio.

Discussion

This large review of patients with glioblastoma treated with surgery and post-operative radiation therapy demonstrated that patients diagnosed in 2005–2006 after the EORTC/NCIC trial was presented were associated with an improved survival compared to patients diagnosed in earlier time periods. The strength of these results is that they represent a population-based cohort from a variety of different medical centers across the nation.

The SEER research data showed that patients with glioblastoma diagnosed in 2005–2006 who underwent surgical resection and post-operative radiation had a median survival of 15 months and a 2 year relative survival of 26%, which was a significant improvement compared to earlier time periods and compares favorably with the outcomes reported in the EORTC/NCIC phase III study (median survival of 14.6 months and a 2 year overall survival of 26.5%) (Fig. 2) [7]. After controlling for known patient characteristics our study revealed being diagnosed in 2005–2006 was associated with a significant hazard ratio of 0.648. This also compares favorably to the adjusted hazard ratio for death in the radiotherapy plus temozolomide group as compared to the radiotherapy group of the EORTC/NCIC study of 0.62 (95% CI 0.51–0.75). The similar survival seen between the two cohorts are encouraging and suggest that the results of the EORTC/NCIC phase III were rapidly implemented into clinical practice across the United States. This quickly translated into a survival benefit for patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. As a comparison, glioblastomas in the SEER research data in those aged 20 years and older who did not undergo the treatment regimen of surgery followed by post-operative radiation therapy had median survival of 5 months or less and much poorer 2 year RS (4% for 2000–2001, 6% for 2002–2003, 7% for 2004, and 7% for 2005–2006 (P < 0.0001 compared to 2000–2001, P = 0.001 compared to 2002–2003, P = 0.14 compared to 2004)). The improvements in 2-year relative survival seen in all glioblastomas, regardless of treatment, appear to be primarily driven by those who received surgery followed by post-operative radiation therapy.

Besides the introduction of temozolomide during the time period studied there were other significant systemic therapeutic advancements in the treatment of glioblastoma including the use of carmustine wafers (polifeprosan 20 with carmustine implant, Gliadel®) and utilization of bevacizumab for recurrent disease [14, 15]. Advances in surgical resection included utilizing awake craniotomies, frameless computer guided stereotaxis, and intra-operative imaging to facilitate aggressive resection and minimize post-operative neurologic complications [16, 17]. Furthermore, there were improvements in the delivery of radiation therapy in the adjuvant and recurrent setting during the time period studied, including using intensity modulation, stereotactic radiosurgery, and brachytherapy [18–22]. All of these advancements may have also contributed towards the improvement in survival that we observed among this cohort, however, individually none of these advances can account for the improved survival seen.

Approximately 80% of the cohort was coded as having undergone a gross total resection which is higher than most published series [7, 23]. A large retrospective series from MD Anderson revealed that 47% of patients were able to undergo a resection removing more than 98% of the tumor based on the post-operative MRI. Patients who underwent removal of greater than 98% of the tumor had a statistically significant improvement in their overall survival. The high percentage of patients in our cohort who underwent gross total resection is likely due to the coding of this variable being based on the operative note per the SEER manual, and not based on residual disease seen on post-operative imaging. A previously published study found that the operative note only correlated with the post-operative MRI findings 30% of the time [24, 25]. The lack of survival benefit based on extent of resection on multivariate analysis is likely a result of this discrepancy in coding. Increasing age was also noted to be associated with a worse hazard ratio which is consistent with other series [26–31]. Despite these potential problems with reporting, the percentage of gross total resection was controlled for when determining the hazard ratio.

This study was limited primarily because of the extent of information available in the SEER research database [32]. No information on radiotherapy technique (total dose, fraction size, radiation volume) was available. Furthermore, we cannot comment on whether chemotherapy was administered, or types of salvage therapy. In spite of this, between 2004 and 2005 the only major development in the treatment of glioblastoma was the presentation of the EORTC/NCIC phase III trial. We hypothesize that the majority of patients diagnosed in 2005–2006 were treated with temozolomide plus post-operative radiation therapy which led to the survival benefit when compared to earlier time periods. Furthermore, the survival benefit and reduction in hazard ratio associated with the time period 2005–2006 was almost in exact concordance with the results of the temozolomide plus post-operative radiation therapy arm of the EORTC/NCIC trial, lending further support to our hypothesis. Finally, we cannot rule out the contribution that changing patterns of care independent from the EORTC/NCIC regimen to improving survival [33]. Recent advances include improved imaging, anti-thrombotic care, and FDA approved second line anti-angiogenic therapy. However, due to the widespread and increasing use of temozolomide over this time period it appears likely to have been a significant contributor to the improved survival we identified.

Conclusion

This large study of patients undergoing post-operative radiation therapy for glioblastoma revealed that patients diagnosed in 2005–2006 had a median and 2 year RS of 15 months and 26% in 2005–2006 similar to the median and 2 year overall survival of 14.6 months and 26% seen in the EORTC/NCIC phase III study. These results are encouraging and suggest that the current treatment of glioblastoma nationwide is now associated with an improved survival compared to previous time cohorts.

References

Tran B, Rosenthal MA (2010) Survival comparison between glioblastoma multiforme and other incurable cancers. J Clin Neurosci 17:417–421. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2009.09.004

Buckner JC (2003) Factors influencing survival in high-grade gliomas. Semin Oncol 30:10–14

Curran WJ Jr, Scott CB, Horton J, Nelson JS, Weinstein AS, Fischbach AJ, Chang CH, Rotman M, Asbell SO, Krisch RE (1993) Recursive partitioning analysis of prognostic factors in three Radiation Therapy Oncology Group malignant glioma trials. J Natl Cancer Inst 85:704–710

DeAngelis LM (2001) Brain tumors. N Engl J Med 344:114–123. doi:10.1056/NEJM200101113440207

CBTRUS (2010) CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2004–2007

Laperriere N, Zuraw L, Cairncross G, Cancer Care Ontario Practice Guidelines Initiative Neuro-Oncology Disease Site Group (2002) Radiotherapy for newly diagnosed malignant glioma in adults: a systematic review. Radiother Oncol 64:259–273

Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJ, Belanger K, Brandes AA, Marosi C, Bogdahn U et al (2005) Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 352:987–996. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa043330

Stupp R, van den Bent MJ, Hegi ME (2005) Optimal role of temozolomide in the treatment of malignant gliomas. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 5:198–206

Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Taphoorn MJ, Janzer RC, Ludwin SK, Allgeier A, Fisher B, Belanger K et al (2009) Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol 10:459–466. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70025-7

Linz U (2010) Commentary on effects of radiotherapy with concomitant, adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial (Lancet Oncol.2009;10:459–466). Cancer 116:1844–1846. doi:10.1002/cncr.24950

National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Cancer Statistics Branch (Released April 2010, based on the November 2009 submission) Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program (www.seer.cancer.gov) SEER*Stat Database: Incidence—SEER 17 Regs Research Data + Hurricane Katrina Impacted Louisiana Cases, Nov 2009 Sub (1973–2007 varying)—Linked To County Attributes—Total U.S., 1969–2009 Counties

Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, May S (2008) Applied survival analysis: regression modeling of time-to-event data. Wiley-Interscience, Hoboken

Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute SEER*Stat software (seer.cancer.gov/seerstat). Version 7.0.4

Westphal M, Hilt DC, Bortey E, Delavault P, Olivares R, Warnke PC, Whittle IR, Jaaskelainen J, Ram Z (2003) A phase 3 trial of local chemotherapy with biodegradable carmustine (BCNU) wafers (Gliadel wafers) in patients with primary malignant glioma. Neuro Oncol 5:79–88. doi:10.1215/S1522-8517-02-00023-6

Stark-Vance V (2005) Bevacizumab and CPT-11 in the treatment of relapsed malignant glioma (Abstract). Neuro-oncology 7:369

Meyer FB, Bates LM, Goerss SJ, Friedman JA, Windschitl WL, Duffy JR, Perkins WJ, O’Neill BP (2001) Awake craniotomy for aggressive resection of primary gliomas located in eloquent brain. Mayo Clin Proc 76:677–687

Sanai N, Mirzadeh Z, Berger MS (2008) Functional outcome after language mapping for glioma resection. N Engl J Med 358:18–27. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa067819

Cardinale R, Won M, Choucair A, Gillin M, Chakravarti A, Schultz C, Souhami L, Chen A, Pham H, Mehta M (2006) A phase II trial of accelerated radiotherapy using weekly stereotactic conformal boost for supratentorial glioblastoma multiforme: RTOG 0023. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 65:1422–1428. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.02.042

Larson DA, Suplica JM, Chang SM, Lamborn KR, McDermott MW, Sneed PK, Prados MD, Wara WM, Nicholas MK, Berger MS (2004) Permanent iodine 125 brachytherapy in patients with progressive or recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. Neuro Oncol 6:119–126

Narayana A, Yamada J, Berry S, Shah P, Hunt M, Gutin PH, Leibel SA (2006) Intensity-modulated radiotherapy in high-grade gliomas: clinical and dosimetric results. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 64:892–897. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.05.067

Prisco FE, Weltman E, de Hanriot RM, Brandt RA (2002) Radiosurgical boost for primary high-grade gliomas. J Neurooncol 57:151–160

Simon JM, Cornu P, Boisserie G, Hasboun D, Tep B, Hardiman C, Valery CA, Delattre JY, Dormont D, Baillet F et al (2002) Brachytherapy of glioblastoma recurring in previously irradiated territory: predictive value of tumor volume. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 53:67–74

Lacroix M, Abi-Said D, Fourney DR, Gokaslan ZL, Shi W, DeMonte F, Lang FF, McCutcheon IE, Hassenbusch SJ, Holland E et al (2001) A multivariate analysis of 416 patients with glioblastoma multiforme: prognosis, extent of resection, and survival. J Neurosurg 95:190–198. doi:10.3171/jns.2001.95.2.0190

Albert FK, Forsting M, Sartor K, Adams HP, Kunze S (1994) Early postoperative magnetic resonance imaging after resection of malignant glioma: objective evaluation of residual tumor and its influence on regrowth and prognosis. Neurosurgery 34:45–60; discussion 60-1

Albert FK, Forsting M (2003) Resection and prognosis. J Neurosurg 98:225–226; author reply 226

Gorlia T, van den Bent MJ, Hegi ME, Mirimanoff RO, Weller M, Cairncross JG, Eisenhauer E, Belanger K, Brandes AA, Allgeier A et al (2008) Nomograms for predicting survival of patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma: prognostic factor analysis of EORTC and NCIC trial 26981-22981/CE.3. Lancet Oncol 9:29–38. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70384-4

Curran WJ Jr, Scott CB, Horton J, Nelson JS, Weinstein AS, Fischbach AJ, Chang CH, Rotman M, Asbell SO, Krisch RE (1993) Recursive partitioning analysis of prognostic factors in three Radiation Therapy Oncology Group malignant glioma trials. J Natl Cancer Inst 85:704–710

Scott CB, Scarantino C, Urtasun R, Movsas B, Jones CU, Simpson JR, Fischbach AJ, Curran WJ Jr (1998) Validation and predictive power of Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) recursive partitioning analysis classes for malignant glioma patients: a report using RTOG 90-06. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 40:51–55

Jeremic B, Milicic B, Grujicic D, Dagovic A, Aleksandrovic J (2003) Multivariate analysis of clinical prognostic factors in patients with glioblastoma multiforme treated with a combined modality approach. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 129:477–484. doi:10.1007/s00432-003-0471-5

Lutterbach J, Sauerbrei W, Guttenberger R (2003) Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors in patients with glioblastoma. Strahlenther Onkol 179:8–15. doi:10.1007/s00066-003-1004-5

Lamborn KR, Chang SM, Prados MD (2004) Prognostic factors for survival of patients with glioblastoma: recursive partitioning analysis. Neuro Oncol 6:227–235. doi:10.1215/S1152851703000620

Yu JB, Gross CP, Wilson LD, Smith BD (2009) NCI SEER public-use data: applications and limitations in oncology research. Oncology 23

Grossman SA, Ye X, Piantadosi S, Desideri S, Nabors LB, Rosenfeld M, Fisher J, Consortium NABTTCNS (2010) Survival of patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma treated with radiation and temozolomide in research studies in the United States. Clin Cancer Res 16:2443–2449. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3106

Acknowledgments

This work was presented at the Annual American Society of Clinical Oncology Meeting June 3rd, 2011.

Funding for Therese Dolecek and Bridget McCarthy was supported by the Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States (CBTRUS) that receives support from the American Brain Tumor Association, the National Brain Tumor Society, the Pediatric Brain Tumor Foundation and from the Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under contract # HHSN261201000576P.

Conflict of interest

No author indicated a conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Koshy, M., Villano, J.L., Dolecek, T.A. et al. Improved survival time trends for glioblastoma using the SEER 17 population-based registries. J Neurooncol 107, 207–212 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-011-0738-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-011-0738-7