Abstract

Liponeurocytoma is not exclusive to the cerebellar or fourth ventricular location. Since its inclusion in the central nervous system tumor classification in 2000, six cases with similar radiological, histomorphological and immunohistochemical features have also been described in the lateral ventricles. In the present study, we report clinical, radiological and pathological findings of three supratentorial and one cerebellar liponeurocytoma from our records, evaluated with an extensive panel of immunohistochemistry, and review published cases in the literature. The immunohistochemical pattern of supratentorial and infratentorial liponeurocytomas are almost identical, which indicates that these tumors are homologous.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cerebellar liponeurocytoma as a distinct entity was first introduced in the WHO 2000 classification of tumors of central nervous system [1]. This low grade tumor with consistent neuronal, variable astrocytic and focal lipomatous differentiation was described predominantly in the cerebellar hemispheres and the vermis and rarely in the fourth ventricle [2]. Subsequently, occurrence of similar tumors was described in the supratentorial compartment within lateral ventricles. To date, 33 published cases of cerebellar [2–6] and 6 cases of supratentorial intraventricular liponeurocytoma [7–12] are on record. In this study, we present the clinical, radiological and immunohistochemical features of 4 cases of liponeurocytomas, one arising in the cerebellum and 3 others located supratentoreally, and review the similarities and differences between the tumors in two different intracranial locations.

Materials and methods

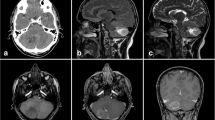

We reviewed our records at the Department of Neuropathology, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore, South India, a tertiary care center for neurological disorders, over a period of 10 years (1999–2008). Among 66 cases of central neurocytomas (constituting 0.6% of neurosurgical biopsies) reported between 1999 and 2008, 3 cases of supratentorial intraventricular liponeurocytomas and a single case of cerebellar liponeurocytoma were found. The clinical presentation, neuroimaging features, and treatment details are summarized in Table 1 (Fig. 1a–c).

The excised tumor tissue received was processed for paraffin embedding and sectioning. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin stain for routine histological evaluation. Immunohistochemistry was performed on representative sections using indirect immunoperoxidase technique with antibodies to Glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP; monoclonal, 1:50 dilution, BioGenex, USA), Synaptophysin (polyclonal, 1:50 dilution; Dako USA), Neuronal nuclear antigen (NeuN; monoclonal, 1:50 dilution; BioGenex), Neurofilament (NF; monoclonal, 1:1,000 dilution; BioGenex), Chromogranin A (ChgA; monoclonal, prediluted; BioGenex), MIB-1 (monoclonal, 1:30 dilution; BioGenex;), MAP-2 (monoclonal, 1:1,000; Sternberger Monoclonals, USA), p53 (monoclonal, 1:100 dilution; BioGenex) and S-100 (polyclonal, 1:100 dilution; BioGenex). The immunohistochemical features are tabulated in Table 2.

Results

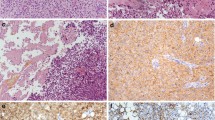

Histopathological examination of the tumor from all the three cases in the supratentorial compartment showed sheets and lobules of monomorphic round cells interspersed by arborizing network of capillaries and multiple large punched out empty spaces (Fig. 2a). The tumor cell nuclei were round with speckled chromatin and micronucleoli, and pale eosinophilic to clear cytoplasm. The empty spaces in the tumor represented large fat vacuoles surrounded by a thin rim of cytoplasm (Fig. 2a). Dispersed foci of cell-free, finely fibrillary neuropil was seen punctuating the tumor. Diligent search did not reveal mitotic activity in any of the cases. Interstitial foci of hemorrhage and fibrin was prominent in initial tumor sample of Case 1, while in the recurrent tumor, lipidization of the tumor cells was prominent. Numerous hyalinized blood vessels and predominantly lipidized zones were seen in Case 2. In all the three supratentorial tumors, the cytoplasm of the cells and small areas of cell free fibrillary matrix were diffusely immunopositive for Synaptophysin (Fig. 2b) and MAP-2 (Fig. 2c) while focally positive for Neurofilament (Fig. 2d) and Chromogranin A (Fig. 2e). In Case 3, no NF labeling was demonstrable, though diffuse positivity was present for MAP-2. Tumor cell nuclei demonstrated immunopositivity for NeuN (Fig. 2f). GFAP immunostaining highlighted glial cells in the midst of neurocytoma cells and surrounding the blood vessels (Fig. 2g). The lipid-laden tumor cells showed thin rim of cytoplasm immunolabeled by synaptophysin in Cases 1 and 3, while GFAP and S100 positive glial fibres were found encircling some of the lipid spaces (Fig. 2g, h). The MIB-1 labeling index in all the cases was uniformly less than 1% (Fig. 2i) except for the recurrent tumor in Case 1, which was focally 3–4%. p53 immunolabeling was negative in all. The posterior fossa tumor in Case 4, had identical histology and immunoprofile as the supratentorial group, with MIB-1 labeling index of less than 1%.

Sheets of tumor cells with small, monomorphic nuclei and clear cytoplasm seen intersected by large lipid vacuoles (a) dispersed in a fine, neuropil stroma that shows diffuse positivity for synaptophysin (b). Tumor cells and matrix show strong labeling with MAP-2 (c) but focal labeling with NF (d) and ChgA (e) particularly surrounding vacuoles. Uniform nuclear labeling seen with NeuN in tumor cells (f). Scattered cells and perivascular glial cells highlighted by GFAP (g) with vacuoles encircled by GFAP (g) and S100 (h). Proliferative activity as seen by MIB-1 is low (i) (a HE ×180, immunoperoxidase; b–d ×180, e,g ×280, f ×120, h ×180)

Discussion

To date, only six cases of supratentorial intraventricular central liponeurocytomas have been reported in the medical literature, all involving lateral ventricles (Table 3). The mean age at presentation was 38.5 years (age range 30–59 years), with male preponderance (male:female = 3:1). In the present study, all the three supratentorial tumors involved bilateral lateral ventricles, with extension into third ventricle in one case (Case 2). Mean age at presentation was 32 years (range 30–36 years), and all three were males. The age distribution and anatomical localization was essentially similar to central neurocytomas that are typically located supratentorially in the lateral ventricle and/or the third ventricle, clinically manifesting in the third and fourth decades of life [13]. In contrast, cerebellar liponeurocytomas involve the cerebellar hemispheres, vermis and occasionally cerebellopontine angle, and occurs in older age group (fourth to sixth decades) [2] similar to Case 4 in the present study, that occurred in a 50-year-old lady.

Cerebellar liponeurocytomas on CT scans appear as hypo- to isodense tumors. The hypodensity has the attenuation values of fatty tissue, with variable enhancement on contrast. On MRI, the tumors appear hypointense on T1WI with scattered foci of hyperintensity in the form of mottling, laminated or serpiginous streaks, corresponding to fat, with minimal, heterogenous contrast enhancement. On T2W imaging, the tumors appear mildly hyperintense with absent or minimal edema. The presence of fat as determined on CT scan and T1W MRI are very characteristic and help distinguish this rare neoplasm from medulloblastomas or ependymomas of the fourth ventricle [14]. In published cases of supratentorial ventricular liponeurocytomas, the tumors are non-homogenous lesions with mixed signals indicating presence of fat and possibly calcium [7] with enhancing heterogenously on CT [9, 11] and MRI [7, 11]. Cranial CT scan in the present series showed hypodensity (Case 2) corresponding to microscopically predominant fat component and hyperdensity (Case 3) reflecting high cellularity. On MRI, hyperintensity on T1WI was noted in the recurrent tumor (Case 1), corresponded to increased fat component in the tumor.

Microscopically, cerebellar liponeurocytoma has a biphasic appearance, composed of sheets of isomorphic round tumor cells, having neurocytic and focal lipomatous differentiation. The tumor cells and lipidized cells express the neuronal markers synaptophysin, neuron specific enolase, MAP-2 and focally GFAP [2]. The histological features of all the cases in the present study were comparable to cerebellar liponeurocytoma. Central neurocytomas have similar histology and immunoprofile except for the absence of fat component.

The immunostaining profile of previously published cases of supratentorial central liponeurocytomas (Table 4) document uniform positivity for neuronal markers like synaptophysin [7, 9–11], and neuron-specific enolase (NSE) [10, 11]. Expression of glial markers GFAP and S-100 is limited to scattered reactive astrocytes [10, 11] and a few tumor cells along with tumor matrix [11]. The tumor cells are negative for NF [9–11], epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) [9], CK and Chg A [11]. MIB-1 labeling index was 4% [11] and 5% [9] and increased to 5.8% in the recurrent tumor [9].

George et al. suggest that lipomatous differentiation occurs in synaptophysin positive neurocytic cells with progressive accumulation of lipid and coalescence of neurocytic cells [9]. Rim positivity for GFAP has also been demonstrated in lipidized tumor cells suggesting pluripotent immunophenotypic expression [11]. By electron microscopy, the demonstration of neurosecretory granules, and clear and dense core vesicles in some of the cells with osmiophilic lipid spaces confirms lipidization of the neurocytic cells or metaplastic transformation of neuroectodermal cells into adipocytes [10, 11].

Heterologous elements like fat, melanocytes [15] and skeletal muscle [16] have been described within central neurocytomas. Horoupian et al. suggested the origin of central neurocytoma from pluripotent progenitor cells in the germinal layers, and therefore the presence of fat cells within them is not surprising [7]. Apart from 29 reported cases of cerebellar liponeurocytoma [2], the presence of fat cells or lipidization of neuroepithelial tumor cells of the central nervous system have also been described in sporadic cases of cerebellar astrocytomas [17], multiple intraspinal low-grade astrocytoma mixed with lipoma (astrolipoma) [18], a low-grade astrocytoma variant in pediatric age (lipoastrocytoma) [19], frequently in pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma [20], occasionally in glioblastoma [21], 88 cases of ependymomas [22], 1 case of mixed cerebral glio-neuronal tumor [23], 22 cases of supratentorial PNET [24, 25], and 1 case of extracerebellar but partly infratentorial PNET with a glioblastoma component [26].

Central neurocytomas have a benign clinical course but local recurrence follows incomplete resection. Radiotherapy is advocated for residual tumors [27, 28]. The 5-year survival rate of cerebellar liponeurocytomas is 48%, but this should be interpreted with caution because of rarity of this tumor and lack of systematic follow-up [2]. Recurrence rate in cerebellar liponeurocytomas is 31% [5], but as it occurs following long disease-free interval, repeat surgery is preferable to radiotherapy, as objective evidence of usefulness of this therapeutic modality is lacking [29]. Radiotherapy may be considered in cases with incomplete resection or in tumors with high proliferation index documented on histology [6]. Of the six reported cases, one recurred following partial excision [9] and the rest were lost to follow-up. Similarly in the present study, one case recurred after 9 years and 4 months of initial surgery, and rest of the cases were lost to follow-up. An increase in lipomatous component was demonstrable both radiologically and histologically in supratentorial tumors, similar to cerebellar liponeurocytomas [30], reflecting slow evolution of lipomatous metaplasia. Following molecular and genetic studies, an International Consortium evaluating 20 cases of cerebellar liponeurocytomas, suggested a relationship to central neurocytomas, with high frequency of TP53 missense mutations [31].

Conclusion

We suggest a change in nomenclature of these tumors to ‘liponeurocytoma’ rather than the restrictive ‘cerebellar liponeurocytomas’, to encompass all the sites of occurrence. Defining the exact prognosis of these rare tumors and determine management protocols awaits documentation of more number of cases with long-term follow-up.

References

Kleihues P, Chimelli L, Giangaspero F (2000) Cerebellar liponeurocytoma. In: Kleihues P, Cavenee WK (eds) Pathology and genetics of tumors of the central nervous system. IARC Press, Lyon, pp 110–111

Kleihues P, Chimelli L, Giangaspero F, Ohgaki H (2007) Cerebellar liponeurocytoma. In: Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Weistler OD, Cavenee WK (eds) WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system. IARC, Lyon, pp 110–112

Hortobágyi T, Bódi I, Lantos PL (2007) Adult cerebellar liponeurocytoma with predominant pilocytic pattern and myoid differentiation. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 33(1):121–125

Patel N, Fallah A, Provias J, Jha NK (2009) Cerebellar liponeurocytoma. Can J Surg 52(4):E117–E119

Limaiem F, Bellil S, Chelly I, Bellil K, Mekni A, Jemel H, Haouet S, Zitouna M, Kchir N (2009) Recurrent cerebellar liponeurocytoma with supratentorial extension. Can J Neurol Sci 36(5):662–665

Châtillon CE, Guiot MC, Roberge D, Leblanc R (2009) Cerebellar liponeurocytoma with high proliferation index: treatment options. Can J Neurol Sci 36(5):658–661

Horoupian DS, Shuster DL, Kaarsoo-Herrick M, Schuer LM (1997) Central neurocytoma: one associated with a fourth ventricular PNET/Medulloblastoma and the second mixed with adipose tissue. Hum Pathol 28:1111–1114

Mena H, Morrison AL, Jones RV, Gyre KA (2001) Central neurocytomas express photoreceptor differentiation. Cancer 91:136–143

George DH, Scheithauer BW (2001) Central liponeurocytoma. Am J Surg Pathol 25:1551–1555

Rajesh LS, Vasishta RK, Chhabra R, Banerjee AK (2003) Case report: central liponeurocytoma. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 29(5):511–513

Kuchelmeister K, Nestler U, Seikmann R, Schachenmayr W (2006) Liponeurocytoma of the left lateral ventricle: case report and review of literature. Clin Neuropathol 25(2):86–94

Wang Z, Fan QH, Zhang ZH, Yu MN, Qiao DF, Song GX (2008) Liponeurocytoma of right lateral ventricle: report of a case. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi 37(1):64–65

Figarella-Branger D, Soylemezoglu F, Burger PC (2007) Central neurocytoma and extraventricular neurocytoma. In: Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Weistler OD, Cavenee WK (eds) WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system. IARC, Lyon, pp 106–109

Alkadhi H, Keller M, Brandner S, Yonekawa Y, Kollias SS (2001) Neuroimaging of cerebellar liponeurocytoma. Case report. J Neurosurg 95(2):324–331

Ng TH, Wong AV, Boadle R, Compton JS (1999) Pigmented central neurocytoma: case report and literature review. Am J Surg Pathol 23:1136–1144

Pal L, Santosh V, Gayathri N, Das S, Das BS, Jayakumar PN, Shankar SK (1998) Neurocytoma/rhabdomyoma (myoneurocytoma) of the cerebellum. Acta Neuropathol 95:318–323

Walter A, Dingemans KP, Weinskin HC, Troust D (1994) Cerebellar astrocytomas with extensive lipidization mimicking adipose tissue. Acta Neuropathol 88:485–489

Roda JM, Gutierrez-Molina M (1985) Multiple intraspinal low grade astrocytomas mixed with lipoma (astrolipoma). J Neurosurg 82:891–894

Giangaspero F, Kaulich K, Cennachi G, Cerasoli S, Lerch K-D, Breu H, Reuter T, Reifenberger G (2002) Lipoastrocytoma: a rare low-grade astrocytoma variant of pediatric age. Acta Neuropathol 103:152–156

Kepes JJ, Rubinstein LJ, Enj LF (1979) Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma: a distinctive meningocerebral glioma of young subjects with relatively favorable prognosis. A study of 12 cases. Cancer 44:1839–1852

Kepes JJ, Rubinstein LJ (1981) Malignant glioma with heavily lipidized (foamy) tumor cells: a report of three cases with immunoperoxidase study. Cancer 47:2451–2459

Ruchoux MM, Kepes JJ, Dhellemmes P, Hamon M, Maurage CA, Lecomte M, Gall CM, Chilton J (1998) Lipomatous differentiation in ependymomas. Am J Surg Pathol 22:338–346

Cenacchi G, Cerasoli S, Giangaspero F (1996) Cerebral mixed neuronal-glial neoplasm with lipidization. An immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 55:626 (abstract)

Krishnamurthy S, Powers SK, Towfighi J (2001) Primitive neuroectodermal tumour of cerebrum with adipose tissue. Arch Pathol Lab Med 125:264–266

Selassie L, Rigotti R, Kepes JJ, Towfighi J (1994) Adipose tissue and smooth muscle in a primitive neuroectodermal tumor of cerebrum. Acta Neuropathol 87:217–222

Ishizawa K, Kan-Nuki S, Kumagai T, Hirose T (2002) Lipomatous primitive neuroectodermal tumor with a glioblastoma component: a case report. Acta Neuropathol 103:193–198

Rades D, Fehlauer F, Lamszus K, Schild SE, Hagel C, Westphal M, Alberti W (2005) Well differentiated neurocytoma: what is the best available treatment? Neuro Oncol 7:77–83

Rades D, Fehlauer F, Schild SE (2004) Treatment of atypical neurocytomas. Cancer 100:814–817

Cacciola F, Conti R, Taddei GL, Buccoliero AM, Di Lorenzo N (2002) Cerebellar liponeurocytoma. Case report with considerations on prognosis and management. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 144(8):829–833

Jenkinson MD, Bosma JJ, Du Plessis D, Ohgaki H, Kleihues P, Warnke P, Rainov NG (2003) Cerebellar liponeurocytoma with an unusually aggressive clinical course: case report. Neurosurgery 53(6):1425–1427

Horstmann S, Perry A, Reifenberger G, Giangaspero F, Huang H, Hara H, Masuoka J, Rainov NG, Bergman M, Heppner FL, Brandner S, Chimelli L, Montagna N, Jackson T, Davis DG, Markesbery WR, Ellison DW, Waller RO, Taddei GL, Conti R, Del Bigio MR, Gonzalez-Campora R, Radhakrishnan VV, Soylemezoglu F, Uro-Caste E, Quian J, Kleihues P, Ohgaki H (2004) Genetic and expression profiles of cerebellar liponeurocytomas. Brain Pathol 14:281–289

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chakraborti, S., Mahadevan, A., Govindan, A. et al. Supratentorial and cerebellar liponeurocytomas: report of four cases with review of literature. J Neurooncol 103, 121–127 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-010-0361-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-010-0361-z