Abstract

We suggest that data from American Sign Language (ASL) provide overt evidence for Partee’s and Stone’s claim that natural language has anaphoric constructions in the temporal and modal domains (Partee 1973; Stone 1997). We provide four arguments. (i) Like nominal and locative expressions, temporal and modal constructions can establish loci that can then be indexed by later pronouns. (ii) As is the case in the nominal and locative domains, anaphoric constructions can involve singular, dual, trial, and plural pronouns. (iii) When the antecedent is existential, patterns of inference obtain which are characteristic of E-type anaphora. (iv) Finally, temporal and modal anaphora give rise to patterns of ‘locative shift’ which are also found with geographical locations. The last observation suggests that temporal and modal reference is particularly similar to locative reference.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

1.1 Theoretical goals

In the tradition of modal and tense logic, it was thought that expressions are only implicitly evaluated with respect to times and possible worlds: variables could denote individuals, but not times or worlds. By contrast, several researchers have argued after Partee (1973) and Stone (1997) that natural language has time- and world-denoting variables—albeit ones that are usually invisible. We provide overt evidence for this conclusion: in American Sign Language (ASL), a single anaphoric expression has nominal, temporal, and modal uses—as well as locative uses. Most of the analysis could be developed using times and possible worlds, or situations/events—although a situation/event-theoretic analysis might ultimately prove preferable.

Two main arguments have been provided for the existence of temporal and modal anaphora in spoken language.

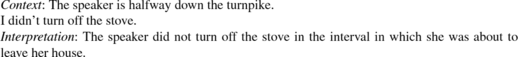

1. Tense and mood have all the readings (deictic, anaphoric, bound, E-type) that pronouns do (Partee 1973; Stone 1997; Brasoveanu to appear; see also Percus 2000). It is thus natural to think that they can function as anaphoric expressions. To give an idea of the argument, we provide in (1) examples that suggest that tense and mood can have deictic readings.

-

(1)

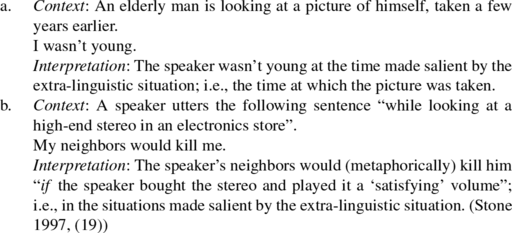

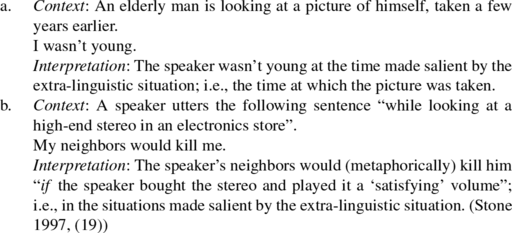

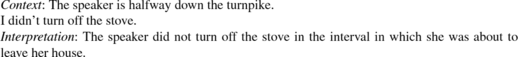

Consider (1a). Partee (1973) argued that an analogous example (‘I didn’t turn off the stove.’) is not properly handled by traditional operator-based theories of tense. These analyses take the past tense to have an existential semantics: PAST F is true at time t if and only if for some time t′ prior to t, F is true at t. Within the operator-based framework, there are only two possible Logical Forms for (1a), depending on the relative scope of negation and the past tense; they are represented in (2a–b), whereas Partee’s own analysis (in terms of temporal anaphora) is illustrated in (2c):

-

(2)

Partee noted that neither (2a) nor (2b) has appropriate truth conditions: (2a) is trivially true (‘there is a past time at which I wasn’t young’—which isn’t informative in the situation at hand), while (2b) is trivially false (‘there is no past time at which I was young’). By contrast, (2c) is appropriate if the time variable t is taken to denote a contextually salient past moment—in the case at hand, the time at which the picture was taken.Footnote 1 Stone (1997) developed a different but related argumentation about (1b), where the modal construction makes reference to worlds that are made salient by the extra-linguistic situation; the reading obtained is that the speaker’s neighbors will kill him in the (closest) worlds in which he buys the stereo and plays it at a ‘satisfying’ volume.

2. The behavior of the word then provides a second argument in favor of the existence of modal anaphora (in English, temporal uses of then might well behave analogously, but they have not been studied in as much detail in the literature). Specifically, modal then behaves in several respects like a (strong) pronoun:

-

(i)

In some languages, modal then is morphologically related to some varieties of pronouns (specifically, correlative pronouns: Bhatt and Pancheva 2005; Bittner 2001);

-

(ii)

Then gives rise to the same implicatures as some (strong) pronouns (Iatridou 1994; Izvorski 1996; Schlenker 2004);

-

(iii)

A semantics can be devised in which an if-clause is treated as a referential term (a definite description: Bittner 2001; Schlenker 2004), and then as a pronoun coreferential with it; Condition C effects are arguably obtained when then c-commands its antecedent (Schlenker 2004).

It is a standard observation that sign language pronouns can refer to locations. (We come back to locative uses in Sect. 6.) We argue that ASL pronouns can have temporal and modal uses as well, and we suggest that time and world reference is particularly similar to locative reference. We present four arguments.

-

(1)

Nominal anaphora in sign language usually involves (i) the establishment of positions in signing space, called ‘loci’, for antecedents; (ii) pointing towards these loci to express anaphora. We show that both properties are also found in the temporal and in the modal domains.

-

(2)

When an ASL pronoun has two or three split antecedents, dual, trial or plural pronouns may simultaneously index several antecedents. The same fact holds in the temporal and modal domains.Footnote 2

-

(3)

Temporal and modal anaphora in ASL can give rise to patterns of inference that are characteristic of E-type pronouns (i.e., pronouns that depend on existential antecedents without being in their syntactic scope).

-

(4)

Temporal and modal anaphora gives rise to instances of ‘locative shift’ in which the locus assigned to a nominal referent ‘moves’ in signing space depending on the location it is associated with. While this pattern has been described for geographical location, we show that it applies to modal and temporal location as well.

The logic of our argument could in principle be applied to some spoken languages. Our main finding is that one and the same pronoun can have nominal, temporal, modal, and locative uses in ASL—and similar facts could conceivably hold in some spoken languages. Thus, we believe it is premature to make any claim about the role of the signed modality per se in our data. On the other hand, the details of our argument must per force rely on peculiarities of sign language anaphora—most notably the existence of loci and of a mechanism of locative shift.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Some background on methods and prior work on sign language pronouns is included in Sect. 1.2. The basics of temporal and modal indexing are laid out in Sect. 3, followed by the arguments from split antecedents (Sect. 4), E-type inferences (Sect. 5) and locative shift (Sect. 6)—and some concluding remarks (Sect. 7).

1.2 Methods

Before we introduce our findings, we should say a word about our elicitation method. It involved three steps.

-

(i)

First, we elicited sentences of interest with a deaf native signer (deaf child of deaf, signing parents; he is called Inf 1 below). Our emphasis was on the construction of controlled paradigms, usually of two to four sentences. Various means were used to help the consultant sign the relevant paradigms: written English sentences with the intended meaning could be provided, transcriptions of target sentences could be given, or the author could sign target sentences (which could then be modified or corrected by the consultant). All examples were videotaped.

-

(ii)

Second, we showed the resulting videos to our consultant. For all crucial data, we asked him to rate the sentences on a 7-point scale. (Additional sentences obtained with a more traditional ‘acceptable/unacceptable’ judgment task are mentioned below, primarily for illustrative purposes.) In one case, we also asked him to provide ordinal judgments; i.e., to rank sentences by degree of acceptability.

-

(iii)

Step (ii) was often repeated several times, often on separate days, in order to assess the stability of our consultant’s judgments. For the crucial examples of Sects. 3 and 4, Step (ii) was repeated with other signers, Inf 2 and Inf 3, showing them the videos obtained with Inf 1 (Inf 2 and Inf 3 are both deaf; Inf 2 acquired signing from birth, with a thirteen-year-old brother and a ten-year-old sister who had both already acquired ASL from Deaf school; Inf 3 started signing at two and a half years and had two younger deaf siblings). They too were asked to provide judgments on a 7-point scale. As for the more intricate judgments of Sects. 5 and 6, which involved more complex inferential tasks, or comparative judgments involving long paradigms, they were just repeated with Inf 1.Footnote 3

In the following, sign language sentences are glossed in capital letters. Non-manual markings are omitted, except in expressions that include the pronouns under study; in this case, re__ indicates that the signer has raised eyebrows during the production of the pronoun, and le__ indicates that the eyebrows are lowered. Subscripts correspond to the establishment of locations (‘loci’) in signing space—thus a INFECTED is the word ‘infected’ signed in locus a; similarly, a [WORK IX-a FRENCH CITY] refers to an entire string of words associated with locus a (with IX-a pointing towards direction a as well). Letters are assigned from right to left from the signer’s perspective—and in some examples we give a rough representation of the loci’s positions using a diagram. Pronouns, glossed as IX (for ‘index’), can point back towards previously established loci. In such cases, the locus is suffixed to the pronoun, so that IX-a is a pronoun that points towards (or ‘indexes’) locus a; the numbers 1 and 2 correspond to the position of the signer and addressee respectively. (In Sect. 6, we use 1a and 1c to distinguish two loci that are associated to the signer but have different localizations—the former to the right, the latter more to the left from the signer’s perspective.) Importantly, indexesFootnote 4 can also be used to establish a locus, as is discussed in Sect. 2. It should be noted that sometimes it is not easy to distinguish between the ‘default’ position of a sign (often in front of the signer), and a position that corresponds to a particular locus. This is especially true when a sequence of words is signed in a particular locus; which words are in their neutral position and which are assigned to the locus can then be hard to determine.

2 Pronouns in sign language

See Schlenker (2011) for a similar discussion.

Pronouns in sign language have been the object of considerable interest, due in part to their apparent difference from their spoken language counterparts. As was already mentioned, ASL pronouns (and sign language pronouns quite generally) can be realized by way of pointing. For present purposes, the key mechanism involves two steps: (i) first, an antecedent establishes a position in signing space (a ‘locus’), (ii) second, the pronoun is realized by pointing back towards this locus. Several cautionary notes must be added, however:

(i) First, this two-step mechanism is not the only way to realize anaphora in ASL. To mention just two further complexities: sometimes pointing can be towards a ‘default locus’ which has not been explicitly introduced and sometimes null pronouns can be used (see for instance Neidle et al. 2000; Sandler and Lillo-Martin 2006; Schlenker 2011 for discussion).

(ii) Second, there are several respects in which ASL pronouns differ from English pronouns; to mention but two: the person system has been claimed to be limited to the first vs. non-first person opposition (e.g., Meier 1990; Sandler and Lillo-Martin 2006), and any case morphology is absent. These peculiarities will play no role in what follows.

Pointing can be used to realize various sorts of anaphora, including E-type anaphora (see Schlenker 2011 for a detailed discussion of the latter). In (3), we see examples of locus assignment to expressions of direct reference (here proper names), definite descriptions and indefinite descriptions. (Only meaning can distinguish between the latter two.)

-

(3)

Since there appears to be an arbitrary number of possible loci, it was suggested that the latter do not spell out morphosyntactic features, but rather are the overt realization of indices (Lillo-Martin and Klima 1990; Sandler and Lillo-Martin 2006). The latter are not overtly realized in spoken languages; the fact that they are in sign languages makes it particularly interesting to use them to bring new evidence to bear on questions of anaphora.

Importantly, we do not claim that all uses of pointing in sign language are pronominal in nature, only that some uses of pointing are clearly pronominal—namely those which involve an antecedent establishing a locus, give rise to anaphoric interpretations, and allow for dual, trial and plural pronouns. It is important to note that there are at least four additional uses of pointing which have been discussed in the literature.

-

(i)

As was indicated above in our glossing conventions, pointing can be used to establish a locus (e.g., Sandler and Lillo-Martin 2006:297).

-

(ii)

Bahan et al. (1995) argue that in some cases an index plays the role of a definite determiner.

-

(iii)

It has sometimes been claimed that pointing can be used solely for purposes of ‘comparing’ two situations (e.g., in Winston 1995). It is currently unclear what this amounts to in terms of contemporary semantic theory (for instance, it cannot be excluded that some of these uses involve propositional anaphora, but the situation is currently unclear); but this possibility will have to be kept in mind in our discussion.

-

(iv)

Pointing signs can also have a locative use, with a meaning akin to there, as is for instance discussed in Bahan et al. (1995) (who note some phonological differences between locative and determiner uses). We come back to this issue in Sect. 6.

While we will have to keep these various uses in mind, we argue below that the cases of pointing we study are indeed pronominal, for the following reasons: (i) they involve an antecedent that establishes a locus (Sect. 3); (ii) they allow for dual, trial and plural pronouns when there are split antecedents (Sect. 4); (iii) they give rise to anaphoric interpretations, including highly non-trivial ones (‘E-type readings’; Sect. 5). One cautionary remark is in order, however: saying that ASL pronouns have temporal and modal uses does not mean that these uses are in all respects identical to those of English pronouns; our point is simply that pronominal uses of indexing in ASL can be found in the temporal and modal domains.

3 Temporal and modal indexing

We start by establishing that the two-step mechanism described above for nominal anaphora is at work for temporal and modal anaphora as well; an antecedent establishes a locus and a pointing sign towards this locus serves to express anaphora.

3.1 Temporal indexing

We can see in (4) that the same possibilities are open for temporal anaphora as were displayed for nominal anaphora in (3).

-

(4)

As can be seen, expressions of direct reference (here, indexicals), when-clauses (which are semantically similar to definite descriptions of times), and existential time quantifiers (sometimes) can all give rise to patterns of anaphora with the same pronoun IX as in the nominal case. Importantly, loci appear in the usual signing space, which is in front of the signer. Although the words for tomorrow and yesterday are signed on the ‘time line’, which is on a sagittal plane (tomorrow is signed in the front, yesterday towards the back), no pointing occurs towards it; we will come back to this point in the conclusion.

While it is particularly simple, the paradigm in (4) is not conclusive. There are two difficulties.

-

(i)

First, as we noted at the outset, it has been claimed in the sign language literature that loci can be established to compare situations (Winston 1995). Thus it would be desirable to have examples that could not be interpreted in terms of ‘comparison’ between two situations. This raises another difficulty, however: when only one locus is involved, signers may prefer to use a ‘default’ location, which might make the interpretation of the facts more complicated. So it is optimal to have examples that involve a single antecedent, and also ones that involve two.

-

(ii)

Second, the complexity of the paradigm is reduced to a minimum because the verbs we used are weather verbs, which take no individual arguments. But this also introduces a problem: these verbs are ambiguous between a nominal and a verbal use, and we cannot exclude the possibility that the pronouns are anaphoric to SNOW and RAIN in their nominal uses.Footnote 6

Both difficulties are addressed in the following paradigms, which involve judgments on a 7-point scale. The results are averaged over 3 subjects (with 3 judgments from Inf 1, 1 from Inf 2, and 2 from Inf 3; we computed an average per subject, and averaged over the three subjects). The full judgments are given in the Appendix (numbers between square brackets refer to the videos in which the examples or the judgments were recorded; as seen in the Appendix, averaging over the six judgments gives very similar results to the average per subject).

-

(5)

-

(6)

While there are no clear world indexicals or world proper names, modals such as can are standardly analyzed as existential quantifiers over possible worlds and if-clauses have occasionally been treated as definite descriptions of possible worlds (e.g., Bittner 2001; Schlenker 2004; Bhatt and Pancheva 2005). Both cases can give rise to locus indexing in ASL.Footnote 7

-

(7)

Here too, however, the two difficulties we discussed in connection to our argument about temporal anaphora arise as well. The following paradigm addresses them.

-

(8)

-

(9)

At this point, we have established that temporal and modal reference can be associated with indexing. We will now show that this indexing mechanism shares a further property with nominal indexing: dual, trial, and plural pronouns can simultaneously have several antecedents.

4 Split antecedents

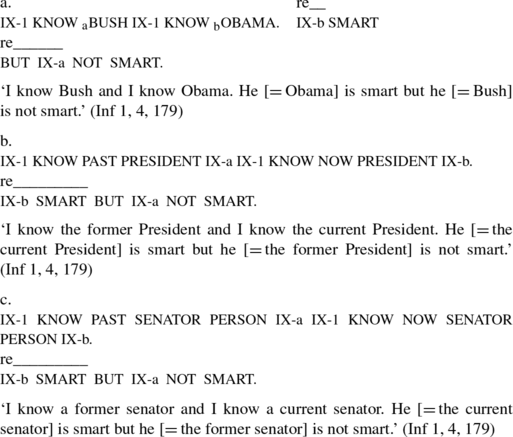

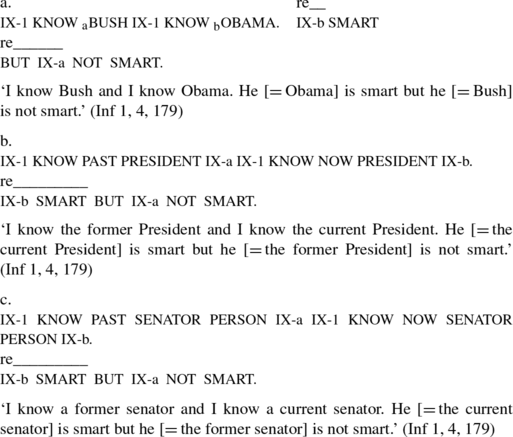

ASL pronouns can have split antecedents, and in such cases they can simultaneously index several loci. When the antecedents taken together denote two objects, a dual pronoun tends to be preferred to a plural pronoun, as in the locative case in (10b); when they denote three objects, a trial or plural form can be used, as shown in (10b) (possibly with a slight preference for the trial form).Footnote 8

-

(10)

We show that dual, trial, and plural pronouns can be used in the temporal and in the modal domains as well; this will demonstrate that the variety of pronominal forms found in the nominal and locative case is also found in the temporal and modal case.

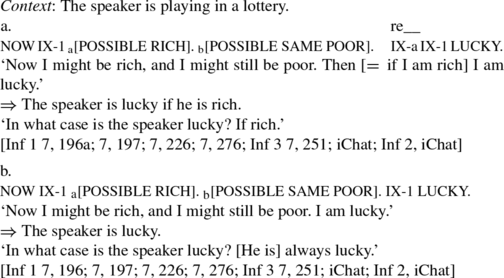

4.1 Split temporal antecedents

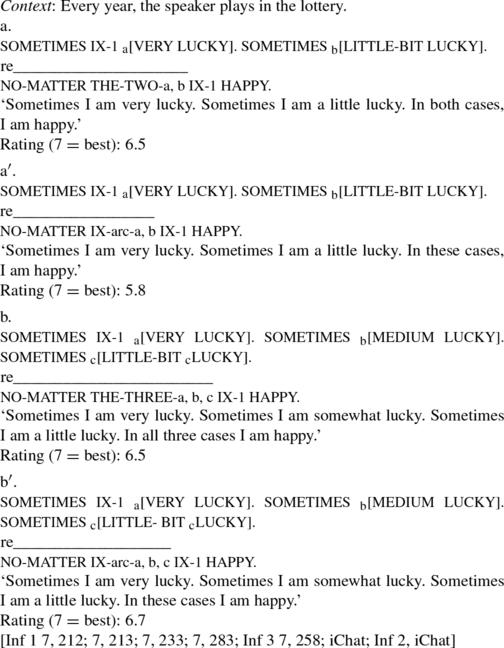

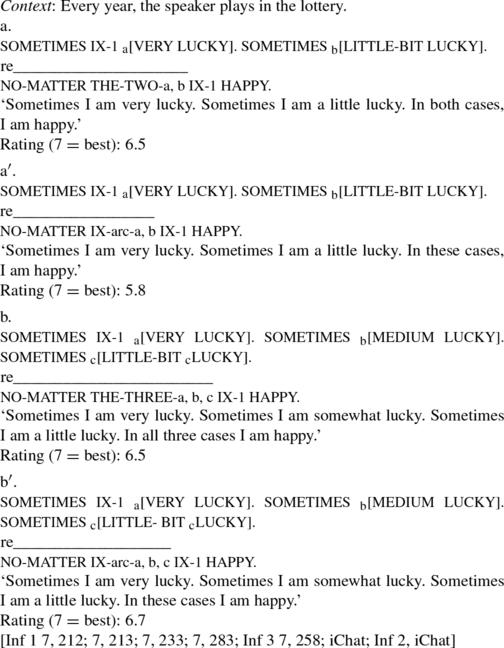

The examples in (11a′–b′) show that plural pronouns (glossed as IX-arc) can simultaneously index several loci; the result is more felicitous when three loci are indexed than when just two are. In addition, dual pronouns (glossed as THE-TWO) and trial pronouns (glossed as THE-THREE) are acceptable in the expected cases, as shown in (11a–b).

-

(11)

We conclude that dual, trial, and plural pronouns can have temporal uses.

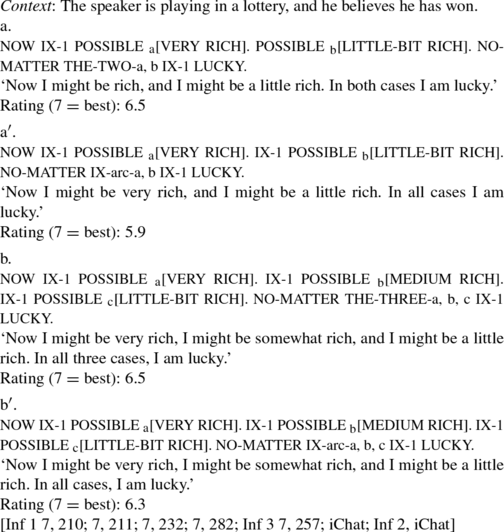

4.2 Split modal antecedents

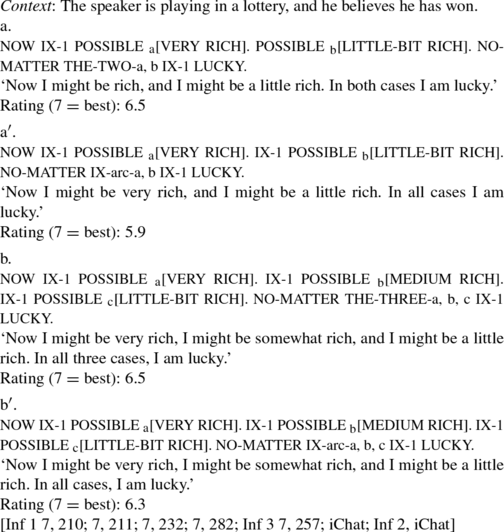

A similar pattern can be found with modal anaphora involving split antecedents, (12a′–b′) show that a plural pronoun can have three split modal antecedents; when there are only two, the sentence is slightly less acceptable. And (12a–b) show that dual and trial pronouns can be used as well.

-

(12)

At this point, then, we have shown that irrespective of number, ASL pronouns can have temporal and modal uses.

5 E-type inferences

Having seen that the form of pronouns seems to be compatible with temporal and modal uses, we turn to interpretive properties that are characteristic of pronouns. In (13), they is dependent on the quantifier some of the students without being in its syntactic scope (i.e., without being c-commanded by it). This has been called an ‘E-type’ or sometimes a ‘donkey’ use; one of its properties is that can be paraphrased with a certain description—here: the students who came to the party.

-

(13)

These readings have been subjected to considerable scrutiny in the syntactic and semantic literature because they are a challenge to the view that c-command is a necessary condition for binding (e.g., Geach 1962; Evans 1977; Kamp 1981; Heim 1982). Here we will not be concerned with their proper analysis, but rather with the question of their existence in the temporal and modal domains.

Partee (1973, 1984) and Stone (1997) argue that E-type readings exist in the temporal and modal domains as well:

-

(14)

The idea is that in (14a), the tense of the second clause refers to the time at which Mary woke up during the night, and that in (14b) the mood of the second clause refers to the (accessible) worlds in which it snows tomorrow. In other words, in this case as well, we find two key properties of E-type readings: the anaphoric expression depends on its antecedent without being c-commanded by it, and it can be paraphrased in terms of a definite description.

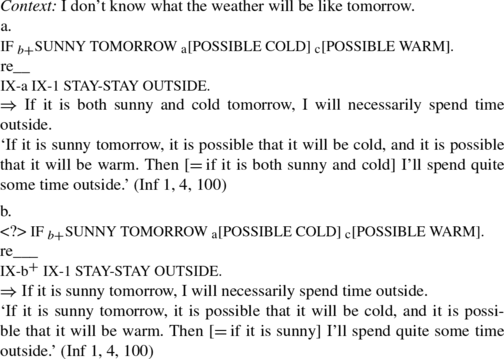

Interestingly, in more complex examples, E-type readings are quite difficult to emulate with mere propositional anaphora. In (15a–b), one could (wrongly) posit that then refers to the proposition that it is sunny, or to the proposition that it is cold (or sometimes cold). But neither option is adequate: then refers neither to the times/worlds in which it is sunny, nor to those in which it is cold, but rather to those in which it is both sunny and cold.

-

(15)

With this background in mind, we turn to some E-type inferences that are obtained in ASL in the temporal and in modal domains.

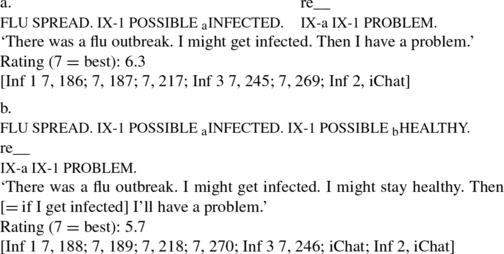

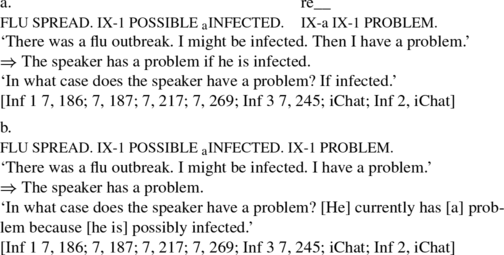

5.1 E-type inferences in the temporal domain

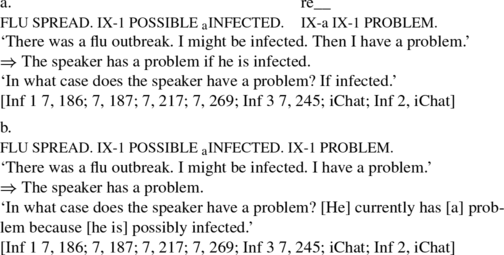

We start with simple examples we considered earlier, but this time with a focus on the inferences they give rise to. We provide the crucial inferences, together with a sample of the questions/answers that were used to establish them with Inf 1. (The task was given three times on separate days.)

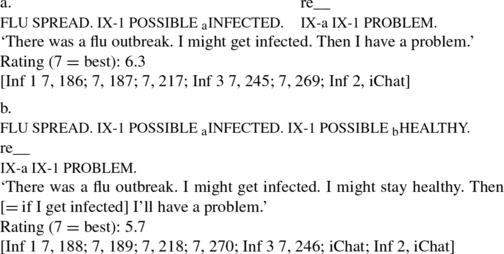

-

(16)

We already discussed the acceptability of (16a). Here we are interested in its meaning, in particular in comparison to (16b), which is identical except that it fails to include the pronoun IX-a. The semantic difference is clear: in (16a), the second sentence asserts that when the speaker is infected, he has a problem; in (16b), the second sentence asserts that in general the speaker has a problem. The pronoun plays very much the role of the English adverbial then in the translation—with the difference that in ASL IX-a can just as well have nominal and locative uses.

The same semantic contrasts are found when several potential antecedents are simultaneously present:

-

(17)

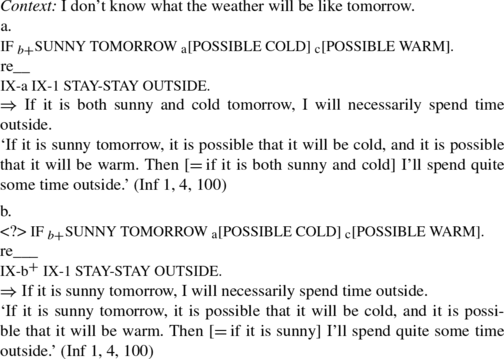

Finally, similar readings obtain in some more complex cases in which the E-type pronoun must, as in (15a), refer to the intersection of the times that satisfy the temporal clause (here: while it is sunny) and the main clause (here: it is sometimes cold), as in (18a) (Note that a. and b. are continuations of the discourse that starts on the first line of (18)).

-

(18)

In (18b), by contrast with (18a), pointing is towards the locus introduced by SUNNY, and the reading is quite different; our consultant understands that whenever it is sunny, I spend time outside (but it must be noted that this example is degraded). These fine-grained judgments can be established by way of an inferential task: after the consultant has signed the sentences in (18), one gives him several potential inferences that one could draw from the sentence, asking him which are in fact licensed. It can be shown in this way that the pronoun IX-a in the second clause (18a) refers to those times at which it is both sunny and cold.Footnote 9

In summary, when an ASL pronoun is dependent on a temporal antecedent that does not c-command it, we obtain patterns that are characteristic of E-type anaphora.

5.2 E-type inferences in the modal domain

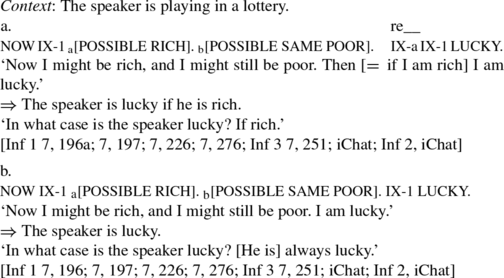

Similar generalizations hold in the modal domain. In (19a), a conditional reading is obtained due to the presence of the (modal) pronoun IX-a; an unconditional reading is obtained in (19b), where IX-a is absent.

-

(19)

The same contrasts hold when several potential antecedents are present:

-

(20)

As was the case in the temporal domain, in more complex cases, we find examples in which the observed data could not easily be emulated in terms of propositional (rather than E-type) anaphora. Specifically, in (21a), the second clause is understood to make a claim about the intersection of (i) situations in which it is sunny, and (ii) situations in which it cold—hence the inference that if it is both sunny and cold, I spend time outside (note that world knowledge would, if anything, lead to an inference that if it is both sunny and warm, I spend time outside; the linguistic form of the sentence is crucial in obtaining the inference we do get).

-

(21)

By contrast, in (21b), where the pronoun IX-b indexes the locus corresponding to SUNNY, we get a different inference, namely: if it is sunny, I’ll spend time outside—which is expected if the pronoun has as its antecedent the if-clause. (We have contradictory data on the acceptability of (21b), hence more work is needed on this type of example.)

We conclude that in the modal as well as in the temporal domain, a pronoun that depends on an antecedent that does not c-command it gives rise to inferences that are characteristic of E-type anaphora.

6 Locative shift

When an individual has been associated with a location in previous discourse, one can refer to him by pointing towards the locus associated with that location (though pointing to the original locus of the individual is often possible too). Thus in (22), from Padden (1988), locus c is introduced in the first sentence to refer to a geographical location, one to which the agent has walked; in the second sentence, this same locus is used to refer to the agent herself.

-

(22)

Strikingly, locative shift can be applied in our temporal and modal examples. We start with a simplified version of our paradigm to make the generalization clear. (The full judgments are given below.) (23) displays a locative example: the loci a and b are respectively associated with FRENCH CITY and AMERICAN CITY in the first sentence. But in the second sentence, the pronouns in bold, which index these loci, refer to John rather than to these locations.

-

(23)

Similar facts hold in the temporal domain. In the first sentence of (24), the loci a and b are respectively associated with times at which John was a college student and a college professor. In the second sentence, however, the pronouns in bold index the same loci but refer to John rather than to time periods.

-

(24)

The same pattern is found in the modal domain:

-

(25)

The loci a and c, which are initially associated with possible situations in which John is a college student and a college professor, respectively, are used in the second sentence to refer to John himself.

The verb help makes it possible to test more fine-grained patterns, however. It exists in two versions: the one we used in (23), (24) and (25) is a ‘plain verb’, which finds its arguments in standard syntactic positions. But there is also a related help that is an agreement verb, and takes incorporated subject and incorporated object agreement markers. This makes it possible to test the relative preference for locative agreement vs. lack thereof in a variety of minimally different constructions:

-

(i)

cases in which the plain verb help is used;

-

(ii)

cases in which the corresponding agreement verb is used, which in turn gives rise to two possibilities: (1) the agreement marker may be present without being doubled by a full pronoun; (2) the agreement may be doubled by a full pronoun.

We present the full paradigms below. Our consultant’s patterns of preference are subtle and were established using ordinal rankings (from 1st [= best] to 6th [= worst], since there were 6 examples in each paradigm),Footnote 10 as well as cardinal judgments on a 7-point scale [1 = worst, 7 = best]. Each task was done twice (on separate days). We do not aim to understand what explains these patterns of preference. But we note that essentially the same patterns are found in the locative, temporal, and modal paradigms. Specifically, in all three cases: (i) locative/temporal/modal shift is (weakly) preferred over lack thereof; (ii) among examples with shift, the preference is: b4 [= agreement verb + full pronoun] > b3 [= agreement verb − full pronoun] > a2 [= plain verb]. This close similarity across the three domains suggests that we are dealing with the same grammatical phenomenon. (As always, data from further consultants should be tested.)Footnote 11

-

(26)

-

(27)

-

(28)

7 Conclusion

We have provided three arguments to show that ASL provides overt evidence for Partee’s and Stone’s claim that natural language has time- and world-denoting devices of anaphora; specifically: (i) IX can have temporal and modal uses; (ii) the same conclusion extends to IX-arc, THE-TWO and THE-THREE; (iii) the patterns of inference obtained when the pronoun is not in the syntactic scope of its antecedent are characteristic of E-type anaphora. A fourth argument suggests that (iv) temporal and modal anaphora is particularly similar to locative anaphora, in that all three cases give rise to instances of ‘locative shift’.

What do these data bring to existing arguments for the existence of temporal and modal anaphora? In English, the word then has temporal and modal uses, and it has been argued to behave very much like a (strong) pronoun (Iatridou 1994; Izvorski 1996; Schlenker 2004); but it is limited to temporal and modal uses. By contrast, pronominal uses of the ASL words IX, IX-arc, THE-TWO, and THE-THREE are remarkable in that they simultaneously have nominal, locative, temporal, and modal uses. This strongly suggests that the same anaphoric system is at work in all four domains.

The main generalizations are consistent with an analysis in which temporal, modal, and locative anaphora are mediated through reference to times, possible worlds, and locations (three distinct categories), or to a single category of situations (or event/states), which are more fine-grained than times, worlds, or locations. But on any analysis, it is crucial that (i) sign language displays anaphoric reference to modal-like and temporal-like entities, just as was claimed for spoken languages by Partee and Stone; and that (ii) there is a natural sub-class that includes times, possible worlds, and locations, but excludes individuals, so as to account for the patterns of locative, temporal, and modal shift that we observed.Footnote 12 The latter requirement might well be easier to satisfy in a semantics that countenances situations and individuals rather than times, worlds, locations, and individuals, but more work is needed to decide this issue.

One final point: in all cases discussed in this paper, anaphoric reference made use of the normal signing space. However some designated ‘time lines’ have been described for several sign languages, including ASL and LSF. This raises two questions: first, is anaphoric indexing possible within these time lines? Second, in cases of temporal reference, what determines the choice between these times lines and the normal signing space?

With respect to the first question, Emmorey (2002) described three time lines in ASL:

-

(i)

the ‘deictic time line,’ which ‘extends forward from the dominant shoulder and is perpendicular to the body,’ and is for instance used to situate ‘tomorrow’ (forward) or ‘yesterday’ (backwards) (p. 108);

-

(ii)

the ‘anaphoric time line,’ which ‘extends diagonally across signing space,’ and where ‘temporal meaning is derived form the narrative’ (p. 110);

-

(iii)

the ‘sequence time line,’ which is ‘parallel to the body and extends left to right,’ and represents ‘early to later periods or moments in time’ (p. 111).

We have only investigated the deictic time line, and have done so in a highly incomplete fashion. Despite several attempts, we were not able to elicit any clear examples in which signers could point to that line; they preferred to use the normal signing space instead. We make no claim that this reflects a general impossibility, as more research is clearly needed to establish the facts (see also Rathmann 2005; Engberg-Pedersen 1993 for relevant data, including temporal anaphora, in American and in Danish Sign Language).

With respect to the second question, one might want to adopt a mixed ontology in which, say, the deictic time line only involves moments, while situations or events/states can appear in the normal signing space. More research is needed to determine whether this speculation is plausible.

Notes

Example (1) is more compelling in French, as in (i), which is in the imperfect—a tense which, unlike the simple past in English, has no existential reading at all:

-

(i)

As mentioned, Partee’s original example was different (Partee 1973):

-

(ii)

Partee argues that no existential interpretation of the past tense accounts for the data: “Such a sentence clearly does not mean either that there exists some time in the past at which I did not turn off the stove or that there exists no time in the past at which I turned off the stove.” The difficulty is that when implicit domain restrictions are taken into account, there is nothing to block an analysis in which this sentence means: there is not time in a (given) salient interval D at which I turned off the stove. This problem does not arise in (i) because the French imperfect never has existential readings to start with (thus a sentence with the imperfect is just deviant if no interval is made salient by the discourse or by the extra-linguistic situation).

-

(i)

Thanks to Anna Szabolcsi for suggesting that we consider this possibility.

This methodology is of course not that of a controlled experiment, but it could potentially pave the way for one in the future.

We use the pair index/indexes to refer to pointing signs; and the pair index/indices to refer to variable subscripts in logic and linguistics.

Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for pointing out this difficulty.

Note that we do not claim that only the modal is indexed in these examples. The precise interface between indexing and interpretation is left for future research. Here we will be content to note that (i) modals can be associated to loci; and that (ii) pronouns that index these loci receive an interpretation that is consistent with modal anaphora.

Here is an example of an inferential task we used, corresponding to (18). The consultant’s answers are in bold (UNK = unknown).

a. Pointing on the right [= locus a in (18)]. Can one infer from this that:

-

1.

I spend time outside whenever it is sunny? NO

-

2.

I spend time outside whenever it is cold? UNK

-

3.

I spend time outside whenever it is both (= at the same time) sunny and cold? YES

b. Pointing in the middle, upwards [= locus b in (18)]. Can one infer from this that:

-

1.

I spend time outside whenever it is sunny? YES

-

2.

I spend time outside whenever it is cold? UNK

-

3.

I spend time outside whenever it is both (= at the same time) sunny and cold? YES

-

1.

While we only report comparative acceptability, we also asked our consultant to assess the absolute acceptability of the examples, as follows:

-

(i)

“How bad is degree of acceptability 6 (i.e., how bad is the worst)?” “—Not good, weird—but understandable.”

-

(ii)

“If you had to put a ‘cut-off’ between acceptable vs. unacceptable, where would you put it?” “I would say the bottom 3 ranks (involving verb or pronoun toward middle) are unacceptable (“bad ASL”) but all are clear.”

-

(i)

See also Engberg-Pedersen (1993:87) for related examples in Danish Sign Language. Our example in (26) makes reference to a moment in the past. Similar facts hold for future examples (Inf 1, 4, 70).

A connection between tense and spatiotemporal adverbials is explored in a series of works by Demirdache and Uribe-Etxebarria. See for instance Demirdache and Uribe-Etxebarria (2005) for references.

Our examples were typically tested with other sentences, many of which involved binding-theoretic violations—i.e., violations of a semantic rather than syntactic nature. This is somewhat important to avoid biasing consultants towards ‘good’ responses whenever the syntax of our examples is acceptable. Note, however, that in Inf 3’s last session, she uniformly gave relatively high ratings. (The lowest rating she gave in that session was a 4.)

References

Bahan, B., J. Kegl, D. MacLaughlin, and C. Neidle. 1995. Convergent evidence for the structure of determiner phrases in American sign language. In FLSM VI, Proceedings of the sixth annual meeting of the formal linguistics society of Mid-America, vol. 2, eds. L. Gabriele, D. Hardison, and R. Westmoreland, 1–12. Bloomington: Indiana University Linguistics Club Publications.

Bhatt, Rajesh, and Roumyana Pancheva. 2005. Conditionals. In The blackwell companion to syntax, vol. 1, eds. Martin Everaert and Henk van Riemsdijk, 638–687. Oxford: Blackwell.

Bittner, Maria. 2001. Topical referents for individuals and possibilities. In Proceedings from SALT XI, eds. Rachel Hastings, Brendan Jackson, and Zsófia Zvolensky, 36–55. Ithaca: Cornell University.

Demirdache, Hamida, and Myriam Uribe-Etxebarria. 2005. Aspect and temporal modification. In Aspectual inquiries, studies in natural language and linguistic theory, vol. 62, part 2, eds. Paul Kempchinsky and Roumyana Slabakova, 191–221. doi:10.1007/1-4020-3033-9_9.

Emmorey, Karen. 2002. Language, cognition and the brain. insights from sign language. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum and Associates.

Engberg-Pedersen, Elisabeth. 1993. Space in Danish Sign Language. International studies on sign language and communication of the Deaf, vol. 19. Munich: SIGNUM.

Evans, Gareth. 1977. Pronouns, quantifiers and relative clauses. Canadian Journal of Philosophy 7(4): 777–797.

Geach, Peter. 1962. Reference and generality. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Heim, Irene. 1982. The semantics of definite and indefinite noun phrases. PhD diss., University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Iatridou, Sabine. 1994. On the contribution of conditional Then. Natural Language Semantics 2: 171–199.

Izvorski, Roumyana. 1996. The syntax and semantics of correlative proforms. In Proceedings of NELS 26, ed. Kiyomi Kusumoto, 133–147. Amherst: GLSA.

Kamp, Hans. 1981. A theory of truth and semantic representation. In Formal methods in the study of language, eds. J.A.G. Groenendijk, T.M.V. Janssen, and M.J.B. Stokhof, 277–322. Amsterdam: Mathematical Centre.

Liddell, Scott K.. 2003. Grammar, gesture and meaning in American Sign Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lillo-Martin, Diane, and Edward S. Klima. 1990. Pointing out differences: ASL pronouns in syntactic theory. In Theoretical issues in sign language research, eds. Susan D. Fischer and Patricia Siple, 191–210. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Meier, Richard. 1990. Person Deixis in American Sign Language. In Theoretical issues in sign language research, eds. Susan D. Fischer and Patricia Siple, 175–190. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Neidle, Carol, Judy Kegl, Dawn MacLaughlin, Benjamin Bahan, and Robert G. Lee. 2000. The syntax of American Sign Language: Functional categories and hierarchical structure. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Padden, Carol. 1988. Grammatical theory and signed languages. In Linguistics: The Cambridge survey, vol. 2, ed. Frederick J. Newmeyer, 250–266.

Partee, Barbara. 1973. Some structural analogies between tenses and pronouns in English. The Journal of Philosophy 70: 601–609.

Partee, Barbara. 1984. Nominal and temporal anaphora. Linguistics and Philosophy 7: 243–286.

Percus, Orin. 2000. Constraints on some other variables in syntax. Natural Language Semantics 8(3): 173–229.

Rathmann, Christian. 2005. Event structure in American Sign Language. PhD diss., University of Texas at Austin, Austin.

Sandler, Wendy, and Diane Lillo-Martin. 2006. Sign language and linguistic universals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schlenker, Philippe. 2004. Conditionals as definite descriptions (a referential analysis). Research on Language and Computation 2(3): 417–462.

Schlenker, Philippe. 2011. Donkey anaphora: The view from sign language (ASL and LSF). Linguistics and Philosophy 34(4): 341–395.

Stone, Matthew. 1997. The anaphoric parallel between modality and tense. IRCS Report 97-06. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Winston, Elizabeth Ann. 1995. Spatial mapping in comparative discourse frames. In Language, gesture, and space, eds. Karen Emmorey and Judy S. Reilly, 87–114. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Jonathan Lamberton, David Rivera and Maleni Chaitoo for help with the ASL data. I am very grateful to Gaurav Mathur for making several helpful suggestions; participants to the first Venice FEAST (2010) also provided useful feedback. Special thanks to Jonathan Lamberton, who has provided exceptionally fine-grained data throughout this research, and has checked and corrected the transcriptions of the videos cited in this article. The paper was improved thanks to comments by four anonymous reviewers for Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, and by Editor Maria Polinsky. This work was supported in part by an NSF grant (BCS-0802671), and by a Euryi grant from the European Science Foundation (‘Presuppositions: A Formal Pragmatic Approach’). Neither foundation is responsible for the claims made here. The research reported in this work also contributes to the COST Action IS1006.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix. Ratings

Appendix. Ratings

We give in the table below the ratings we obtained for the main examples discussed in Sects. 3 and 4. [Inf 1 10.11.02] should be read as: ratings given by consultant Inf 1 on November 2, 2010 (i.e., on 10.11.02 in year.month.day format).Footnote 13

[Inf 1 10.11.02] | [Inf 1 10.11.03] | [Inf 1 10.11.04] | [Inf 3 10.11.04] | [Inf 3 11.02.02] | [Inf 2 11.01.07] | Average over trials | Average over subjects | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(5a) | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 6. 7 | 6.7 |

(5b) | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

(6a) | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 6.8 | 6.8 |

(6b) | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

(8a) | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 6.5 | 6.3 |

(8b) | 7 | 7 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 5.8 | 5. 7 |

(9a) | 6 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 6.3 | 6.4 |

(9b) | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 6.8 | 6.8 |

(11a) | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6. 7 | 6.5 |

(11a′) | 5 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5. 7 | 5. 8 |

(11b) | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6. 7 | 6.5 |

(11b′) | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6.8 | 6. 7 |

(12a) | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 6.7 | 6.5 |

(12a′) | 5 | 5 (‘close to 6’) | 6 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 5.8 | 5.9 |

(12b) | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6.7 | 6.5 |

(12b′) | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6.5 | 6.3 |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schlenker, P. Temporal and modal anaphora in sign language (ASL). Nat Lang Linguist Theory 31, 207–234 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-012-9181-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-012-9181-5