Abstract

Introduction

Acinetobacter baumanii (AB) is a bacterium of concern in the hospital setup due to its ability to thrive in unfavorable conditions and the rapid emergence of antibiotic resistance. Carbapenem resistance in this organism is disheartening, further clouded by the emergence of colistin resistance.

Aim

The present prospective study aims to note the epidemiology, molecular profile, and clinical outcome of patients with colistin resistance AB infections in a multispecialty tertiary care setup in Odisha, Eastern India.

Methods

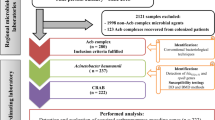

All AB strains received from March 2021 to February 2022, identified by Vitek2 (Biomerieux) and confirmed by oxa-51 genes, were included. Carbapenem and colistin resistance were identified as per CLSI guidelines. Known mutations for blaOXA-23-like, blaIMP, blaVIM, blaKP, lpxA, lpxC, pmrA, pmrB, and plasmid mediated mcr (mcr1-5) were screened by conventional PCR techniques. The clinical outcome was noted retrospectively from case sheets. Data was entered in MS Excel and tabulated using SPSS software.

Results

In the study period, 350 AB were obtained, of which 317(90.5%) were carbapenem resistant (CRAB). Among the CRAB isolates, 19 (5.9%) were colistin resistant (ABCoR). The most valuable antibiotics in the study were tigecycline (65.4% in ABCoI; 31.6% in ABCoR) and minocycline (44.3% in CI; 36.8% in CR). There was a significant difference in mortality among ABCoI and ABCoR infections. bla OXA was the predominant carbapenem resistance genotype, while pmrA was the predominant colistin resistant genotype. There were no plasmid mediated mcr genes detected in the present study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Genus Acinetobacter is a Gram-negative, non-fermenting, catalase-positive, and oxidase-negative bacterium. The remarkable capability of this organism to thrive in dry conditions has caused it to colonize hospital environments and is increasingly associated with hospital acquired infections, particularly in ICUs.Community-acquired A. baumannii (AB) infections have been described chiefly in individuals with co-morbidities [1].

The bacteria have become a primary concern for clinicians worldwide due to their ability to acquire resistance to a wide range of antibacterial agents rapidly. Most AB strains isolated in ICUs are resistant to beta lactams, fluroquinolones, carbapenems, and aminoglycosides [2]. As per ICMR- AMRN data Acinetobacter spp is the predominant non-fermenting GNB isolated, consisting of 12.9% of organisms [3]. Carbapenem resistant AB (CRAB) is also steadily increasing and is 87.5% in 2021 Indian setup [3]. XDR–AB is now recognized as one of the most challenging hospital pathogens to treat and control and is considered a global threat in the healthcare setting [4].

With the crisis of antibiotics and smarter AB bacteria, colistin has become an important therapeutic option either singly or combined with other antibiotics like tigecycline, ampicillin sulbactam, rifampin, and carbapenems [5].Moreover, the newer BLBLIs like ceftazidime avibactam and ceftalozane tazobactam remain ineffective for this difficult bug. However, a grim situation of resistance to colistin among AB has been reported in recent studies [6,7,8].

Genetic mechanisms of colistin resistance in AB have been demonstrated by complete loss of LPS production mediated by mutations in LPS producing genes (lpxA, lpxC, lpxD, and lpxB) [9] or by modification of lipid A components of LPS through mutations in pmrA and pmrB genes [6, 9]. There is an emergence of a plasmid-mediated mobile colistin resistance mediated by mcr genes in many members of Enterobacterales, [10] but has been scant clinical data in Acinetobacter spp in this regard [11]. Plasmids tend to disseminate rapidly across different species, making the already extensive drug resistant strains into pan-drug-resistant ones.

Because of the lesser pool of data regarding the prevalence, clinical outcome, and molecular epidemiology of colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumanii (ABCoR), particularly in our area, it is pertinent to generate data this drug bug combination. The present study aims to bridge the gap in the molecular epidemiology of ABCoR in our area. It is a prospective study describing the epidemiology, molecular profile, and clinical outcome for patients with ABCoR infection in a multispecialty tertiary care setup in Odisha in Eastern India.

Material and method

Study setting

This study was conducted prospectively over one year from March 2021 to February 2022 in the Department of Microbiology at the Institute of Medical Sciences and SUM Hospital in Bhubaneswar, India. It is a premier 1400 bedded tertiary care teaching hospital catering to lower and middle-income patients. All the samples growing AB during the study period from various samples from different wards and ICUs of the hospital were considered. Clinical significance was ascertained before inclusion. Repeated AB isolates obtained from the same patient from the same site and clinically insignificant isolates were excluded from the analysis.

Identification of carbapenem resistant Acinetobacter baumanii and antimicrobial susceptibility testing

The AB was identified using Vitek 2 systems (bioMérieux, Durham, North Carolina, US) using GN cards and susceptibility using AST cards. All interpretations were done using breakpoints of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines [12] except tigecycline, where breakpoints by US Food and Drug Administration were used. An isolate was defined as Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB) if it showed resistance to any of the carbapenems. (MIC ≥ 8 µg/mL for imipenem/doripenem/meropenem).

Detection of MIC of Colistin

MIC of Colistin was detected by broth microdilution method as per CLSI guidelines [12]. The result was interpreted as intermediate if MIC ≤ 2 µg/ml and resistant if MIC ≥ 4 µg/ml. Escherichia coli ATCC 25,922 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27,853 were used as quality control (QC) strains. Also, mcr-1 positive E. coli was used as an internal control.

Clinical characteristics of the patients and the outcome

The patient demographics, clinical history, and outcome of the ABCoR were noted retrospectively from the patient case sheet obtained from the medical records department. For each strain of ABCoR isolated, three successive strains of ABCoI were taken as controls. Isolates were termed hospital acquired infection (HAI) if cultured from specimens collected after 3 days of admission and the patient was admitted for a reason other than the infection in context. In the case of ventilated patients, microbiological culture, Gram stain findings, suggestive clinical picture, and radiological signs were considered while diagnosing Ventilator associated pneumonia (VAP) [13]. Patient demographics, underlying medical conditions, types of infection (HAI/ VAP/ Community acquired), antimicrobial agents given before and after isolation of colistin-resistant A. baumannii isolates, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and clinical outcomes in terms of discharge or death were extracted from the case sheets.

PCR analysis of genetic modifications of known genes

DNA extraction was performed using hot cold technique as described earlier [14], and the resulting DNA obtained was standardized using Thermo Scientific Multiskan Sky Microplate Nanodot. Common genetic mutations conferring carbapenemase production were screened - blaOXA-23-like, blaIMP, blaVIM, blaKPC. Mutations conferring colistin resistance i.e., lpxA, lpxC, pmrA, pmrB, and plasmid-mediated mcr genes (mcr1-5), were also noted.PCR. Table 1 lists the various primers used in the process. All the PCR were performed using Thermofisher Dream Taq master mix 2X in ‘Veriti’ProFlex thermal cycler from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, California, USA).

For each single reaction mixture (25 µL), we used 12µL Taq DNA master mix,1 µL of each primer (10 picomoles; Eurofins Scientific), and 5 mL of template DNA (50 ng/mL) and 6µL of nuclease-free water to maintain volume. The reaction conditions for pmr A, and pmrB gene amplification were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 1 min, 30 cycles at 95 °C for 15 s, 48 °C for 40 s, 72 °C for 30 s, and final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. For lpxA and lpxC reaction, the conditions were initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, 30 cycles at 95 °C for 30 s, 57 °C for 45 s, 72 °C for 1 min, and final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. The amplified product was identified by agarose gel electrophoresis using 1.5% agarose gel with 80–150 V, with the run typically around 1–1.5 h.

Statistical analysis

All consecutively isolated CRAB strains during the study period were processed for phenotypic detection of colistin resistance. The patients from whom the ABCoR was isolated were designated as cases. Controls were the ABCoI patients among the CRAB. For each case, three successive ABCoI patients were taken as controls. Data collected was entered in an excel sheet and interpreted for routine statistics. Clinical data between cases and controls were compared by chi-square and Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Shapiro-Wilk test was used to classify the continuous variables. Normally distributed parameters were analyzed using the Student’s t-test, while non-normally distributed variables were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test. The univariate logistic regression model was used to calculate odds ratios (OR) for the association of risk factors for colistin resistance. P values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS version 26.0(IBM® SPSS® Statistics).

Ethical consideration

The study had received approval from the Institute’s ethics committee via- no. IEC/IMS.SH/SOA/2O22/290. All the processes done were within patient care standards. Written informed consent was obtained from all the patients or the immediate caregiver (whichever is applicable) during admission for all the procedures and sample collection as necessitated for therapeutic purposes. No patient data was disclosed during the study, and diagnostic or therapeutic activity was not hampered.

Results

Isolates of AB

During the study period of the 350 non-repetitive clinically significant isolates of AB obtained, 317(90.5%) were carbapenem resistant (CRAB). CRAB isolates were obtained from various samples like - tracheal aspirates (159, 50.2%), blood (66, 20.8%), wound swab (56, 17.7%), pus (20, 6.3%), tissue (11, 3.5%) CSF (3, 0.9%) and urine (2, 0.6%). There were only 69, 21.8% CRAB isolates from different wards, while rest were from ICUs. Most of the CRAB samples in the present study were from Burn ICUs (76; 23.9%), which also had the highest percentage of ABCoR (8; 42.1%). Colistin resistant AB (ABCoR) was detected in 19 (5.9%) strains, of which 4 (21.1%) were from different wards and the rest from various ICUs. (Table 2)

Sensitivity pattern of AB (Fig. 1)

Of the 19 ABCoR isolates, 2 isolate had MIC = 64 µg/ml, 8 isolates each had MIC = 32 µg/ml and 16 µg/ml and one isolate had MIC of 8 µg/ml. The results of the antimicrobial susceptibility testing of both colistin intermediate and resistant isolates are showed in Table 3. The strains were found to be highly resistant to almost all the drugs tested. The antibiotics which were most susceptible were tigecycline (65.4% in ABCoI; 31.6% in ABCoR) and minocycline (44.3% in ABCoI; 36.8% in ABCoR). Among the BL agents ceftazidime had the highest susceptibility (29.2%). Cefepime (94.7% Resistant in ABCoR vs. 100% in ABCoI), TIC (78.9% resistant in ABCoR vs. 85.9% in ABCoI), CFS (89.5% resistant in ABCoR vs. 94.97% in ABCoI) had lower rate of resistance in colistin resistant isolates than the colistin intermediate ones. Similarly levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin had better sensitivity in ABCoR than ABCoI strains.

Clinical characteristics

The 19 ABCoR were taken as cases to determine the clinical status, and for analysis of various risk factors, three times the cases, i.e., 57 controls were taken. There was no significant difference in age and gender characteristics of the cases and controls. 73.7% of cases and 78.9% of controls were admitted to ICU respectively. When prior ICU days were considered, the mean ICU stay of the patients harboring ABCoR was lesser than those of the controls. The mean duration of getting the colistin-resistant organisms was 5 ± 6.3days of ICU stay. Only 57.9%of ABCoR were hospital-acquired in contrast to 78.9% of controls. There was no significant difference in the development of ABCoR or ABCoI due to nosocomial infections or ventilator-associated pneumonia. When preexisting illnesses were considered, there was a significant difference between cases and controls regarding Type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney diseases, and COPD. Patients having hypothyroidism, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), Chronic Kidney disease (CKD), Pneumonia, post-coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID) pneumonia, and post surgery patients have higher odds of developing ABCoR infections. Pneumonia patients have the highest likelihood of developing ABCoR infections. Prior colistin regimen was offered to 89.5% of cases and 33.5% of controls. Among the ABCoR harboring cases, 10 (52.6%) died. There is a significant difference in mortality of the cases in ABCoR and ABCoI infections. Similarly, the ICU stay duration was longer in cases (16.3 ± 13.3 days) than in controls (6.8 ± 7.3 days).

The ABCoR patients were treated variously as per the treating physician’s discretion and patient’s clinical profile. Out of the 19 cases, 13 patients received combination therapy of tigecycline and carbapenem, 2 patients received tigecycline with cefoperazone sulbactam and 1 patient received tigecycline with a carbapenem and cefoperazone sulbactam. 3 other patients received combination of colistin with tigecycline. There was no significant difference in the colistin added or sparing therapy when outcome in terms of death or discharge was considered.

PCR results of carbapenemase and colistin resistant genes (Fig. 2)

Among the CRAB strains, blaOXA-23 gene was the most common genetic pattern observed in 147(49.3%) strains and in combination with other genes in 54(17.03%) strains. Metallo-β-lactamase genes were present in 46.7% of strains of CRAB. Among these, 24.2% of strains carried blaNDM-1, followed by 17.4% of strains with blaVIM and 17.7% of CRABs with bla IMP. Many strains,i.e.,17.02%, co-harbored MBL and non-MBL genes in this study. Among the 19 ABCoR strains, 52.6% had blaOXA genes alone, serving as the most common pattern, while 42.2% of the stains had multiple genes, including Class A, C, and D beta-lactamase genes.

pmrA was the commonest 14(73.8%) colistin-resistant gene present in our isolates; 6(31.6%) alone and rest along with other genes. Other genes were pmr B (47.4%), lpxA (31.6%), and lpx C (10.5%). None of the strains possessed any plasmid-mediated mcr 1–5 genes (Table 4).

Discussion

A.baumanii is a member of the dreaded group of ESKAPE pathogens as they are often XDR and PDR organisms. In the present study, carbapenem-resistant AB accounted for 90.5% of cases, similar to other previous Indian studies [3]. A worldwide surge in carbapenem resistance has been observed recently, primarily driven by the spread of several international clones [5].

Colistin, or its prodrug CMS, is a key therapeutic option for the treatment of carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii, alone or in combination with other agents such as tigecycline, ampicillin sulbactam, rifampin, and carbapenems [5]. In the present study, the prevalence of colistin resistance in CRAB infections is 5.9% of cases. Over all colistin resistance in a study in northern India was 1.7% in AB [23]. While in a study from South India ABCoR was noted in 8–11% between 2016 and 2019 [24]. The prevalence of ABCoR is estimated to be around 5.3% in the USA [25]. Colistin resistance in CRAB has also been noted in other studies across the globe [6, 7].

In our study, patients with hypothyroidism, COPD and chronic kidney diseases have significant odds of harboring ABCoR. AB from pneumonia cases has a very high likelihood of being colistin-resistant. Prior surgery requiring hospitalization is another risk factor, as described before [26, 27]. Wang et al. described the male sex as an additional risk factor, [27] though in our case we did not find any male preponderance. We had prior exposure to colistin in 89.5% of ABCoR, which was significantly higher than the control group. Similar finding of colistin exposure leading to colistin resistant AB was also seen in other studies [28, 29]. However, acquiring ABCoR strains without prior colistin treatment has also been reported in the literature [30]. In our study, 52.6% of ABCoR harboring cases died, much higher than controls, and the length of ICU stay of cases in cases was also higher than control population of CRAB with ABCoI. Other studies demonstrate that ABCoR infection, in general, has a high mortality rate and that colistin resistance is an independent risk factor for mortality [31, 32]. According to the extensive review by Wong et al., in the case of AB infection, antibiotic resistance drives the outcome of the patients [33].

In the present study, the betalactams quinolones, cefoperazone sulbactam, ticarcillin clavulanic acid, cefepime showed better sensitivity in ABCoR cases than ABCoI patients. Moffatt et al. 9, in their study, have also demonstrated that loss of LPS production in ABCoR strains leads to a greater susceptibility to other antibiotics. Nevertheless, colistin therapy alone, probably because of the drug’s toxicity and the critical nature of patients on treatment, leads to high mortality.

blaOXA−23 like was the most predominant type of carbapenem genes in CRAB isolates in our study, similar to previous studies [34]. Like other Indian studies, we also had very few (10%) blaKPC strains [34]. About 17% of CRAB cases had blaIMP and blaVIM, unlike other previous studies different from other studies [34]. NDM-1 genes were seen in 7/19 ,i.e., 36.8% ABCoR isolates in our study, which is a matter of concern. The presence of IMP and VIM variants together was seen in 12% of our isolates, and this confers a high level of carbapenem resistance in A. baumannii isolates, as well as resistance to all beta lactams except aztreonam, because of their strong hydrolytic efficiency against these antibiotics [35]. As per molecular epidemiology of CRAB this probably belongs to the most widespread IC2 clone known to harbor the acquired OXA-23 carbapenemase [36].

In A. baumannii, two mechanisms of colistin resistance are- mutations affecting the pmrAB, which modifies the lipid A component of LPS. and in the genes lpxA, lpxC, lpxD that cause lack of LPS production. Recent studies have shown that the pmrAB efflux pump may also play a role in colistin resistance in A. baumannii. In our area mutations affecting pmr A superseded other mutations, unlike other studies where mutations in pmrB is the major contributor to colistin resistance in A. baumannii [37, 38]. Multiple mutations in pmrA and lpx A were seen in one isolate, and all the genes tested were mutated in another. Such combinations were also seen in 4 of ABCoI isolates. This observation indicates that mutations in lpxA or B alone and pmrB alone may not be sufficient to induce colistin resistance and support the synergistic activity of mutations within these genes in promoting colistin resistance [37]. A single case of mcr-1 has been detected in Indian set up in ABCoR on the chromosome. However, in the current study, none of the isolates had mcr1-5 genes.

In our study, OXA-23-like enzymes were the common mutations associated with CRAB isolates. Class B metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs) were seen in a lower frequency in A. baumannii like in previous Indian studies. pmrA is a common mutation resulting in ABCoR, and no transferable gene resulting in colistin resistance was noted.

Data availability

Dataset Excel Sheet: The data is openly accessible and can be downloaded for research purposes.

References

Chen CT, Wang YC, Kuo SC, Shih FH, Chen TL, How CK, Yang YS, Lee YT (2018) Community-acquired bloodstream infections caused by Acinetobacter baumannii: a matched case–control study. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 51(5):629–635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmii.2017.02.004

Falagas ME, Karveli EA, Siempos II, Vardakas KZ (2008) Acinetobacter infections: a growing threat for critically ill patients. Epidemiol Infect 136(8):1009–1019. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268807009478

Walia K, Madhumathi J, Veeraraghavan B, Chakrabarti A, Kapil A, Ray P, Singh H, Sistla S, Ohri VC (2019) Establishing antimicrobial resistance surveillance & research network in India: journey so far. Indian J Med Res 149(2):164. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_226_18

Mavroidi A, Katsiari M, Palla E, Likousi S, Roussou Z, Nikolaou C, Platsouka ED (2017) Investigation of extensively drug-resistant Bla OXA-23-producing Acinetobacter baumannii spread in a Greek hospital. Microb Drug Resist 23(4):488–493. https://doi.org/10.1089/mdr.2016.0101

Pogue JM, Mann T, Barber KE, Kaye KS (2013) Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: epidemiology, surveillance and management. Expert Rev Anti-Infect Ther 11(4):383–393. https://doi.org/10.1586/eri.13.14

Lesho E, Yoon EJ, McGann P, Snesrud E, Kwak Y, Milillo M, Onmus-Leone F, Preston L, St. Clair K, Nikolich M, Viscount H (2013) Emergence of colistin-resistance in extremely drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii containing a novel pmrCAB operon during colistin therapy of wound infections. J Infect Dis 208(7):1142–1151. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jit293

López-Rojas R, McConnell MJ, Jiménez-Mejías ME, Domínguez-Herrera J, Fernández-Cuenca F, Pachón J (2013) Colistin resistance in a clinical Acinetobacter baumannii strain appearing after colistin treatment: effect on virulence and bacterial fitness. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57(9):4587–4589. https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.00543-13

Pogue JM, Cohen DA, Marchaim D (2015) Editorial commentary: polymyxin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: urgent action needed. Clin Infect Dis 60(9):1304–1307. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/civ044

Moffatt JH, Harper M, Harrison P, Hale JD, Vinogradov E, Seemann T, Henry R, Crane B, St. Michael F, Cox AD, Adler B (2010) Colistin resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii is mediated by complete loss of lipopolysaccharide production. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54(12):4971–4977. https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.00834-10

Liu YY, Wang Y, Walsh TR, Yi LX, Zhang R, Spencer J, Doi Y, Tian G, Dong B, Huang X, Yu LF (2016) Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect Dis 16(2):161–168.

Khuntayaporn P, Thirapanmethee K, Chomnawang MT (2022) An update of mobile colistin resistance in non-fermentative gram-negative bacilli. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 12:761. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2022.882236

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, 30th edn. CLSI supplement M100. CLSI, Wayne.

Berríos-Torres SI, Umscheid CA, Bratzler DW, Leas B, Stone EC, Kelz RR, Reinke CE, Morgan S, Solomkin JS, Mazuski JE, Dellinger EP (2017) Centers for disease control and prevention guideline for the prevention of surgical site Infection, 2017. JAMA Surg 152(8):784–791

Queipo-Ortuño MI, De Dios Colmenero J, Macias M, Bravo MJ, Morata P (2008) Preparation of bacterial DNA template by boiling and effect of immunoglobulin G as an inhibitor in real-time PCR for serum samples from patients with brucellosis. Clin Vaccine Immunol 15(2):293–296. https://doi.org/10.1128/CVI.00270-07

Kumar S (2016) Phenotypic methods for detection and differentiation of carbapenemases in clinical isolates of enterobacteriaceae [Ph. D. thesis]. Geetanjali University. http://hdl.handle.net/10603/183598

Pawar SK (2019) Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae with special reference to NDM-1 gene in a tertiary teaching hospital [master’s thesis]. Krishna Institute of Medical Sciences University. http://hdl.handle.net/10603/287799

Ahmed ZS, Elshafiee EA, Khalefa HS, Kadry M, Hamza DA (2019) Evidence of colistin resistance genes (mcr-1 and mcr-2) in wild birds and its public health implication in Egypt. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 8(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-019-0657-5

Roer L, Hansen F, Stegger M, Sönksen UW, Hasman H, Hammerum AM (2017) Novel mcr-3 variant, encoding mobile colistin resistance, in an ST131 Escherichia coli isolate from bloodstream infection, Denmark, 2014. Eurosurveillance 22(31):30584. https://www.eurosurveillance.org/content/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.31.30584?crawler=true

Borowiak M, Fischer J, Hammerl JA, Hendriksen RS, Szabo I, Malorny B (2017) Identification of a novel transposon-associated phosphoethanolamine transferase gene, mcr-5, conferring colistin resistance in d-tartrate fermenting Salmonella enterica subsp. Enterica Serovar Paratyphi B. J Antimicrob Chemother 72(12):3317–3324. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkx327

Haeili M, Javani A, Moradi J, Jafari Z, Feizabadi MM, Babaei E (2017) MgrB alterations mediate colistin resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from Iran. Front Microbiol 8:2470

Jayol A, Poirel L, Brink A, Villegas MV, Yilmaz M, Nordmann P (2014) Resistance to colistin associated with a single amino acid change in protein PmrB among Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates of worldwide origin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58(8):4762–4766. https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.00084-14

Zhang W, Aurosree B, Gopalakrishnan B, Balada-Llasat JM, Pancholi V, Pancholi P (2017) The role of LpxA/C/D and pmrA/B gene systems in colistin-resistant clinical strains of Acinetobacter baumannii. Front Lab Med 1(2):86–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.flm.2017.07.001

Kaur S, Chaudhary J, Gupta V (2023) A clinico-microbiological study of blood stream infections in a tertiary referral hospital: colistin resistance & challenges. J Pure Appl Microbiol 17(1):411

Vijayakumar S, Jacob JJ, Vasudevan K, Shankar BA, Francis ML, Kirubananthan A, Anandan S, Gunasekaran K, Walia K, Biswas I, Kaye KS (2021) Colistin resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii is driven by multiple genomic traits: evaluating the role of IS Aba1-driven eptA overexpression among Indian isolates. BioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.07.425695

van Loon K, Voor in ‘t holt AF, Vos MC (2018) A systematic review and meta-analyses of the clinical epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 62(1):e01730-17. https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.01730-17

Zarkotou O, Pournaras S, Voulgari E, Chrysos G, Prekates A, Voutsinas D, Themeli-Digalaki K, Tsakris A (2010) Risk factors and outcomes associated with acquisition of colistin-resistant KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: a matched case-control study. J Clin Microbiol 48(6):2271–2274. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.02301-09

Wang Y, Tian GB, Zhang R, Shen Y, Tyrrell JM, Huang X, Zhou H, Lei L, Li HY, Doi Y, Fang Y (2017) Prevalence, risk factors, outcomes, and molecular epidemiology of mcr-1-positive Enterobacteriaceae in patients and healthy adults from China: an epidemiological and clinical study. Lancet Infect Dis 17(4):390–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30527-8

Kim Y, Bae IK, Lee H, Jeong SH, Yong D, Lee K (2014) In vivo emergence of colistin resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates of sequence type 357 during colistin treatment. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 79(3):362–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2014.03.027

Agodi A, Voulgari E, Barchitta M, Quattrocchi A, Bellocchi P, Poulou A, Santangelo C, Castiglione G, Giaquinta L, Romeo MA, Vrioni G (2014) Spread of a carbapenem-and colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii ST2 clonal strain causing outbreaks in two sicilian hospitals. J Hosp Infect 86(4):260–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2014.02.001

Lertsrisatit Y, Santimaleeworagun W, Thunyaharn S, Traipattanakul J (2017) In vitro activity of colistin mono-and combination therapy against colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii, mechanism of resistance, and clinical outcomes of patients infected with colistin-resistant A. baumannii at a Thai university hospital. Infect Drug Resist 20:437–443. https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S148185

Papathanakos G, Andrianopoulos I, Papathanasiou A, Priavali E, Koulenti D, Koulouras V (2020) Colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii bacteremia: a serious threat for critically ill patients. Microorganisms 8(2):287. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8020287

Wong D, Nielsen TB, Bonomo RA, Pantapalangkoor P, Luna B, Spellberg B (2017) Clinical and pathophysiological overview of acinetobacter infections: a century of challenges. Clin Microbiol Rev 30(1):409–447. https://doi.org/10.1128/cmr.00058-16

Huang ST, Chiang MC, Kuo SC, Lee YT, Chiang TH, Yang SP, Chen TL, Fung CP (2012) Risk factors and clinical outcomes of patients with carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii bacteremia. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 45(5):356–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmii.2011.12.009

Poirel L, Nordmann P (2006) Carbapenem resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii: mechanisms and epidemiology. Clin Microbiol Infect 12(9):826–836. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01456.x

Higgins PG, Dammhayn C, Hackel M, Seifert H (2010) Global spread of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J Antimicrob Chemother 65(2):233–238. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkp428

Nurtop E, Bayındır Bilman F, Menekse S, Kurt Azap O, Gönen M, Ergonul O, Can F (2019) Promoters of colistin resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii Infections. Microb Drug Resist 25(7):997–1002. https://doi.org/10.1089/mdr.2018.0396

Gerson S, Lucaßen K, Wille J, Nodari CS, Stefanik D, Nowak J, Wille T, Betts JW, Roca I, Vila J, Cisneros JM (2020) Diversity of amino acid substitutions in PmrCAB associated with colistin resistance in clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. Int J Antimicrob Agents 55(3):105862. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2019.105862

Rahman M, Ahmed S (2020) Prevalence of colistin resistance gene mcr-1 in clinical isolates Acinetobacter Baumannii from India. Int J Infect Dis 101:81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.09.238

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the valuable support and facilities provided by the Institute of Medical Sciences (IMS) and SUM Hospital throughout this research project.

Funding

This study was not funded by any organisation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

We, the undersigned authors of this research article, hereby declare that we have contributed to this study as follows: BPR-Writing—Original , Methodology Data collection, Visualization. SO-Conceptualization, Data analysis, Writing—Review & Editing. SKD- Methodology Data collection Data analysis. BB-Methodology Data collection, Visualization. IP-Conceptualization, Writing—Review & Editing. KKS- Conceptualization, Writing—Review & Editing, Data analysis. We affirm that all authors have reviewed and approved the final version of this manuscript, and each author takes responsibility for the content and integrity of the work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this study.

Ethical approval

This research was conducted in full compliance with the ethical principles and guidelines set forth by the Institute of Medical Sciences (IMS) and SUM Hospital] IEC/IMS.SH/SOA/2022/290.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Rout, B.P., Dash, S.K., Otta, S. et al. Colistin resistance in carbapenem non-susceptible Acinetobacter baumanii in a tertiary care hospital in India: clinical characteristics, antibiotic susceptibility and molecular characterization. Mol Biol Rep 51, 357 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-023-08982-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-023-08982-5