Abstract

The aim of this study was to determine whether tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) promoter polymorphisms confer susceptibility to periodontitis in ethnically different populations. A literature search was performed using PubMed and Embase and a meta-analysis of the identified studies was conducted to explore the associations between TNF-α −308 A/G, −238 A/G, IL-6 promoter −174 G/C and −572 G/C polymorphisms and periodontitis. Seventeen comparison studies for the TNF-α −308 A/G polymorphism and three studies for the TNF-α −238 A/G polymorphism were included in the meta-analysis. And 16 separate studies for the IL-6 −174 G/C polymorphism and 10 studies for the IL-6 −572 G/C polymorphism were considered in our meta-analysis. Analysis after stratification by ethnicity indicated that the TNF-α −308 A allele was associated with periodontitis in Brazilian, Asian, and Turkish populations (OR = 0.637, 95 % CI = 0.447–0.907, p = 0.013; OR = 0.403, 95 % CI = 0.204–0.707, p = 0.009; OR = 1.818, 95; % CI = 1.036–3.189, p = 0.037). The meta-analysis showed no association between the TNF-α −238 A/G polymorphism and periodontitis. The meta-analysis indicated an association of the IL-6 −174 G/C polymorphisms with periodontitis in Brazilian populations (OR for GG + GC = 2.394, 95 % CI = 1.081–5.302, p = 0.031). Stratification by ethnicity and disease type indicated an association between the IL-6 −572 G allele and chronic periodontitis (OR = 1.585, 95 % CI = 1.030–2.439, p = 0.036), and periodontitis in Europeans (OR = 2.118, 95 % CI = 1.254–3.577, p = 0.005). This meta-analysis demonstrates that the TNF-α −308 A/G polymorphism confers susceptibility to periodontitis in Brazilian, Asian and Turkish populations. The IL-6 −174 G/C polymorphism may confer susceptibility to periodontitis in Brazilians, and the IL-6 −572 G/C polymorphism may be associated with susceptibility to periodontitis in Europeans, and chronic periodontitis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Periodontitis is considered as a chronic inflammatory disease by bacterial infection and it is classified into two categories, namely chronic (CP) and aggressive (AP) [1]. Periodontitis is caused by microorganisms that adhere to and grow on tooth surfaces, along with an overly aggressive immune response against these microorganisms [1]. In some patients, periodontitis may develop with malfunctioning of some components of the immunity system (i.e. under the situation of impaired/insufficient immune response).

Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) is a potent pro-inflammatory cytokine that plays important roles in inflammatory and immune responses, including periodontitis [2]. Several single nucleotide polymorphisms have been identified in its promoter [3]. Of these polymorphisms, G-to-A substitutions at positions −308 and −238 have been intensively studied; these allelic variations could be of functional significance [4]. TNF-α has been found at high levels in the gingival crevicular fluid and inflamed tissues in periodontitis [5]. TNF-α stimulates bone resportion by osteoclast [6] and induces tissue destruction by releasing of the matrix metalloproteinases, which are destructive to the extracellular matrix of ginviva, peritodontal ligaments and alveolar bone [7]. Numerous studies have examined the potential contributions made by TNF-α promoter polymorphisms to periodontitis susceptibility [8–20].

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is a multifunctional cytokine involved in the inflammatory response and in the modulation of immune responses, including B cell and T cell differentiation [21]. IL-6 is regulated mainly at the transcriptional level by regulatory elements in the 5′ flanking region of the gene [22]. In this region, the −174 G/C and −572 G/C polymorphisms are important regulators of transcription [23]. For example, a luciferase reporter vector assay showed that the −174 G construct was expressed significantly higher than the corresponding −174 C construct [24]. The IL-6 −572 G/C polymorphism lies near a potential glucocorticoid receptor element at position −557 to −552 [25]. Furthermore, the −572 G/C polymorphism has been reported to influence levels of circulating C-reactive protein and bone resorption markers in postmenopausal women, and to be associated with several diseases [26, 27]. Subsequently many studies did examine relationships between IL-6 and TNF-α polymorphisms and periodontitis [16–22, 24–26], but studies have produced diverse results.

A meta-analysis provides a powerful means of overcoming the problem of small sample size and inadequate statistical power, especially in genetic studies of complex traits [28–31]. In the present study, we investigated whether the TNF-α promoter −308 A/G and −238 A/G, IL-6 −174 G/C and −572 G/C polymorphisms contribute to the susceptibility of periodontitis by performing a meta-analysis using published data.

Materials and methods

Identification of eligible studies and data extraction

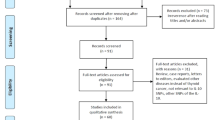

A literature search was conducted for studies that examined associations between the TNF-α promoter −308 A/G and −238 A/G polymorphisms and IL-6 polymorphisms and periodontitis. We utilized the PubMed and Embase citation indexes to identify articles in which the TNF-α polymorphisms were determined in periodontitis patients and controls (up to July 2012). In addition, all references mentioned in the identified articles were reviewed to identify additional studies not indexed by PubMed and Embase. The following key words and subject terms were searched: ‘Tumor necrosis factor’, ‘TNF-alpha’, ‘polymorphism’, “interleukin-6,” “IL-6,” and ‘periodontitis’. The following information was extracted from each study: author, year of publication, ethnicity of the study population, demographics, numbers of cases and controls, and the A allele frequencies of the TNF-α promoter −308 A/G and −238 A/G polymorphisms. Allele frequencies were calculated from the corresponding genotype distributions.

Evaluation of statistical associations

A Chi squared test was used to determine whether the observed genotype frequencies conformed to Hardy–Weinberg (H–W) expectations (http://ihg2.helmholtz-muenchen.de/cgi-bin/hw/hwa1.pl). Meta-analyses were performed using allelic contrast, homozygote contrast, recessive model, and homozygote model. Point estimates of risk, odds ratios (ORs), and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) were determined for each study. Cochran’s Q-statistic was used to assess within and between study variations and heterogeneities [32]. When the heterogeneity test assessed the probability of the null hypothesis, all studies were evaluating the same effect. If a significant Q-statistic (p < 0.10) indicated heterogeneity across studies, the random effects model was used for the meta-analysis, and when heterogeneity was not indicated across studies, the fixed effects model was used. The fixed effects model assumes that genetic factors have similar effects on periodontitis susceptibility across all studies, and that observed variations between studies are caused by chance alone [33]. The random effects model assumes that different studies show substantial diversity, and assesses both within-study sampling errors and between-study variances [34]. The random effects model was used in the presence of significant between-study heterogeneity. The effect of heterogeneity was quantified using a recently developed measure, I2 = 100 % × (Q − df)/Q, [35] where I2 ranges between 0 and 100 % and represents the proportion of inter-study variability attributable to heterogeneity rather than chance. I2 values of 25, 50, and 75 % were defined as low, moderate, and high estimates, respectively. Statistical manipulations were undertaken using the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis computer program (Biosta, Englewood, NJ, USA).

Evaluation of publication bias

Funnel plots are used to detect publication bias, but they require a range of studies of varying sizes and subjective judgments. Thus, in the present study, we evaluated publication bias using Egger’s linear regression test [36], which measures funnel plot asymmetry using a natural logarithm scale of ORs.

Results

Studies included in the meta-analysis

Thirteen studies met the inclusion criteria [8–20]. However, one of these studies contained data of two different groups such as aggressive or chronic periodontitis, and they were treated independently [10]. Fourteen and three separate comparisons of the TNF-α −308 A/G and −238 A/G polymorphisms were considered in the meta-analysis. A total of 17 separate comparisons were considered in our meta-analysis consisting of 1,120 patients with periodontitis and 1,592 controls (14 studies with 884 cases and 1,160 controls for the TNF-α −308 A/G polymorphism; three studies with 236 cases and 432 controls for the TNF-α −238 A/G polymorphism), involving six European, five Asian, four Brazilian, and two Turkish populations. Ethnicity-specific meta-analysis was conducted on these populations. Selected characteristics of the relationships found between the TNF-α polymorphisms and periodontitis are summarized in Table 1.

Seventeen studies met the inclusion criteria [8, 9, 14, 37–50]. However, one of these studies contained data on three different groups for the IL-6 −174 G/C polymorphism and the IL-6 −572 G/C polymorphism [41], and three studies contained the data of both the IL-6 −174 G/C and −572 G/C polymorphisms [16, 17, 27]; these studies were treated independently. A total of 26 separate comparisons were considered in our meta-analysis consisting of 3,323 patients with periodontitis and 2,488 controls (16 studies with 1,887cases and 1,490 controls for the IL-6 −174 G/C polymorphism; 10 studies with 1,436 cases and 998 controls for the IL-6 −572 G/C polymorphism), involving seven European, three Asian, two Brazilian, two Indian, one African, and one Turkish population for the −174 G/C polymorphism and two European, six Asian, one Indian, and one African population for the −572 G/C polymorphism. Ethnicity-specific meta-analysis was conducted on these populations. Selected characteristics of the relationships found between the IL-6 polymorphisms and periodontitis are summarized in Table 2.

Frequencies of the A alleles of the TNF-α promoter −308 A/G polymorphism in the different control groups

The study by Babel et al. showed AA and AG + GG genotype data, but not allele data [14]. Thus, the allele data from the study by Babel et al. was not included in Table 2. The mean frequency of the A allele of the TNF-α −308 A/G polymorphism was 16.0 % among all controls. Asian controls had a lower A allele prevalence (11.6 %) than the controls of the other ethnic groups, in which frequencies varied from 12.9 to 27.1 %. The Brazilian control population had the highest A allele frequency (27.1 %) (Table 3).

Meta-analysis of the association between the TNF-α −308 A/G polymorphism and periodontitis

Meta-analysis was performed on all periodontitis patients and on the patients in each ethnic group. A summary of our meta-analysis findings of the relation between the TNF-α −308 A/G polymorphism and periodontitis is provided in Table 4. Meta-analysis showed no association between the A allele and periodontitis in all subjects (OR = 0.846, 95 % CI = 0.629–1.138, p = 0.269) with between-study heterogeneity (I2 = 49.0 %) (Table 4; Fig. 1). Analysis after stratification by ethnicity indicated that the A allele was associated with periodontitis in Brazilian, Asian and Turkish populations (in respective order: OR = 0.637, 95 % CI = 0.447–0.907, p = 0.013; OR = 0.403, 95 % CI = 0.204–0.707, p = 0.009; OR = 1.818, 95 % CI = 1.036–3.189, p = 0.037), but not in Europeans (OR = 1.034, 95 % CI = 0.772–1.385, p = 0.822) (Table 4; Fig. 2). Stratification by disease type indicated no association between the −308 A allele and aggressive or chronic periodontitis (Table 4).

Meta-analysis of the association between the TNF-α −238 A/G polymorphism and periodontitis

Meta-analysis showed no association between the A allele of the TNF-α −238 A/G polymorphism and periodontitis in all patients (OR 0.757, 95 % CI 0.309–1.740, p = 0.512) without between-study heterogeneity (I2 = 8.56 %) (Table 5). Meta-analyses of the TNF-α −238 A/G polymorphism using the dominant, additive model, or homozygote model showed the same pattern as meta-analysis of the TNF-α −238 A allele, indicating no significant association with periodontitis (Table 5).

Meta-analysis of the IL-6 −174 G/C polymorphism and periodontitis susceptibility

Meta-analysis containing studies in HWE revealed an association between periodontitis and the IL-6 −174 G allele (OR = 1.387, 95 % CI = 1.040–1.849, p = 0.026) (Fig. 3; Table 6). Stratification by ethnicity and disease type indicated no association between the IL-6 −174 G allele and periodontitis in each ethnic group and chronic periodontitis (Table 6). Meta-analysis using the recessive and the homozygote models showed an association of the IL-6 −174 G/C polymorphisms with periodontitis in Brazilian populations (OR for GG + GC = 2.394, 95 % CI = 1.081–5.302, p = 0.031; OR for GG vs. CC = 2.498, 95 % CI = 1.108–5.628, p = 0.027, respectively), but not in European, Asian, and Indian populations (Table 6).

Meta-analysis of the IL-6 −572 G/C polymorphism and periodontitis susceptibility

Meta-analysis stratified by ethnicity and disease type indicated an association between the IL-6 −572 G allele and chronic periodontitis (OR = 1.585, 95 % CI = 1.030–2.439, p = 0.036), and periodontitis in the European group (OR = 2.118, 95 % CI = 1.254–3.577, p = 0.005) (Fig. 4; Table 7). Analysis using the recessive model showed the same pattern for the IL-6 −174 G allele, showing an association between the IL-6 −572 GG genotype and chronic periodontitis, and periodontitis in the European group (Table 7).

Heterogeneity and publication bias

Between-study heterogeneity was found during analyses of the TNF-α −308 A/G polymorphism, such as −308 A allele and the AA + GA genotype in overall and aggressive periodontitis, the AA +GA genotype in chronic periodontitis (Table 4). However, there was no between-study heterogeneity during analyses of the TNF-α −238 A/G polymorphisms (Table 4). The distribution of the TNF-α −308 A/G polymorphism in normal controls was not consistent with H–W equilibrium in one study [11]. Deviation from H–W equilibrium among controls implies potential bias during control selection or genotyping errors. However, excluding the study did not materially affect our results.

The distribution of genotypes of the IL-6 polymorphisms in control groups was consistent with the HWE, except for four studies on the IL-6 −174 G/C polymorphism [39, 40, 44, 45]. There were two studies that did not show HWE [14, 42]. When we excluded these studies, overall results were substantially affected (OR = 1.387, 95 % CI = 1.040–1.849, p = 0.026) (Table 6). Between-study heterogeneity for the IL-6 −174 G/C polymorphism was found among all study subjects and some subgroup analyses. Accordingly, meta-analysis was performed using a random effects model when heterogeneity was present in a population (Table 7). The funnel plot, which is usually used to detect publication bias, was difficult to interpret because we included a relatively small number of studies. Egger’s regression test showed no evidence of publication bias in the meta-analysis (Egger’s regression test p values > 0.1).

Discussion

In the present study, we addressed associations between the TNF-α promoter −308 and −238 A/G polymorphisms and periodontitis susceptibility. Ethnicity-specific meta-analysis showed an association between the TNF-α −308 A allele and periodontitis in Brazilian, Asian, and Turkish populations but not in Europeans. Stratification by disease type indicated no association between the −308 A allele and aggressive or chronic periodontitis and no association was found between periodontitis and the TNF-α −238 A/G polymorphism. We found an association an association between periodontitis and the IL-6 −174 G allele in all study subjects in HWE (OR = 1.387, 95 % CI = 1.040–1.849, p = 0.026). Ethnicity-specific meta-analysis showed an association of the IL-6 −174 G/C polymorphisms with periodontitis in Brazilian populations. We identified an association of the IL-6 −572 G/C polymorphisms with periodontitis in all study subjects (OR for GG + GC = 1.507, 95 % CI = 1.050–2.162). Furthermore, stratification by ethnicity and disease type indicated an association between the IL-6 −572 G allele and chronic periodontitis, and periodontitis in Europeans.

TNF-α is increased in the gingival crevicular fluid and inflamed tissues in periodontitis. Our meta-analysis showed that the TNF-α −308 A/G polymorphism may influence the susceptibility to periodontitis in various ethnic groups. However, it needs to be explained why the TNF-α –308 A/G polymorphism is not associated with periodontitis in European population and plays a different role in different ethnic populations. It can be related with genetic heterogeneity in different populations. Clinical heterogeneity may also explain the discrepancy. Different linkage disequilibrium (LD) patterns may contribute to the discrepancy. This polymorphism may be in LD with a nearby causal variant in one ethnic group but not in another [51]. The difference might arise purely by chance, such as type I error, or because of multiple testing which inflates the type I error. TNF polymorphisms may occur with distinct patterns in ethnically distinct populations [52]. The difference of the allele frequency of the TNF-α −308 A/G polymorphism exists among ethnic groups. In our study, Asian controls had a lower A allele prevalence (11.6 %) than the controls of the other ethnic groups, in which frequencies varied from 12.9 to 27.1 %. The Brazilian control population had the highest A allele frequency (27.1 %).

As IL-6 −174 G/C and −572 G/C polymorphisms increase IL-6 expression, they may be associated with susceptibility to periodontitis [5–7]. IL-6 transcription is influenced by complex interactions determined by these haplotypes. The IL-6 promoter region influences IL-6 gene transcription not by a simple mechanism but rather through complex interactions determined by the haplotype [21]. Because IL-6 polymorphisms and haplotypes are associated with an increased inflammatory response, specifically in the presence of periodontopathogenic bacteria, IL-6 gene may play a key role in the pathogenesis of periodontitis.

This meta-analysis differs from a previous meta-analysis on the relation between the IL-6 polymorphisms and periodontitis risk [53], because in the present study seven more studies were included, and meta-analysis stratified by ethnicity was further conducted. The result of this meta-analysis regarding an association between the IL-6 −174 G/C and −572 G/C polymorphisms and susceptibility to periodontitis is in agreement with the previous study. In addition, our meta-analysis revealed an association between IL-6 −174 G/C polymorphism and periodontitis in Brazilians, and between IL-6 −572 G/C polymorphism and periodontitis in Europeans.

The present study had some limitations that should be considered. First, publication bias and heterogeneity may have distorted the meta-analysis. Second, our ethnicity-specific meta-analysis included data only from European, Brazilian, Asian, and Turkish patients. Thus, our results are applicable only to these ethnic groups. Additional studies are required in other ethnic groups to determine whether the TNF-α polymorphisms confer a risk of periodontitis. Third, the numbers of subjects and studies included in the ethnicity-specific meta-analysis were small. There were only two studies for Turkish population. This analysis may not have enough power to explore the association between TNF-α –308 A/G polymorphism and periodontitis in each ethnic group. Small sample size may have distorted the meta-analysis of the TNF-α −238 A/G polymorphism. There were only three studies available for the meta-analysis of the TNF-α −238 A/G polymorphism. The number of studies included in the meta-analysis was too small to draw definitive conclusion. Interpretation of the data should be done cautiously. Fourth, data were not stratified by sex, disease severity, or environmental variables because of insufficient data.

In conclusion, this meta-analysis demonstrates that the TNF-α −308 A/G polymorphism confers susceptibility to periodontitis in Brazilian, Asian, and Turkish populations, and the IL-6 −174 G/C polymorphism may confer susceptibility to periodontitis in Brazilians, and that the IL-6 −572 G/C polymorphism is associated with susceptibility to periodontitis in Europeans, and chronic periodontitis. Further larger scale studies are required to explore the roles played by the TNF-α and IL-6 genes in the pathogenesis of periodontitis.

References

Armitage GC (1999) Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol 4:1–6

Javed F, Al-Hezaimi K, Salameh Z, Almas K, Romanos GE (2011) Proinflammatory cytokines in the crevicular fluid of patients with peri-implantitis. Cytokine 53:8–12

Allen RD (1999) Polymorphism of the human TNF-alpha promoter–random variation or functional diversity? Mol Immunol 36:1017–1027

D’Alfonso S, Richiardi PM (1994) A polymorphic variation in a putative regulation box of the TNFA promoter region. Immunogenetics 39:150–154

Engebretson SP, Lamster IB, Herrera-Abreu M, Celenti RS, Timms JM, Chaudhary AG, di Giovine FS, Kornman KS (1999) The influence of interleukin gene polymorphism on expression of interleukin-1beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in periodontal tissue and gingival crevicular fluid. J Periodontol 70:567–573

Loos BG, John RP, Laine ML (2005) Identification of genetic risk factors for periodontitis and possible mechanisms of action. J Clin Periodontol 32(Suppl 6):159–179

Brenner DA, O’Hara M, Angel P, Chojkier M, Karin M (1989) Prolonged activation of jun and collagenase genes by tumour necrosis factor-alpha. Nature 337:661–663

Erciyas K, Pehlivan S, Sever T, Igci M, Arslan A, Orbak R (2010) Association between TNF-alpha, TGF-beta1, IL-10, IL-6 and IFN-gamma gene polymorphisms and generalized aggressive periodontitis. Clin Invest Med 33:E85

Costa AM, Guimaraes MC, de Souza ER, Nobrega OT, Bezerra AC (2010) Interleukin-6 (G-174C) and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (G-308A) gene polymorphisms in geriatric patients with chronic periodontitis. Gerodontology 27:70–75

Menezes NG, Colombo AP (2008) Lack of association between the TNF-alpha −308 (G/A) genetic polymorphism and periodontal disease in Brazilians. Braz Oral Res 22:322–327

Guzeldemir E, Gunhan M, Ozcelik O, Tastan H (2008) Interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha gene polymorphisms in Turkish patients with localized aggressive periodontitis. J Oral Sci 50:151–159

Maria de Freitas N, Imbronito AV, Neves AC, Nunes FD, Pustiglioni FE, Lotufo RF (2007) Analysis of IL-1A(−889) and TNFA(−308) gene polymorphism in Brazilian patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis. Eur Cytokine Netw 18:142–147

Zhu XL, Meng HX, Xu L, Zhang L, Chen ZB, Shi D (2007) Relationship between tumor necrosis factor A-308 gene polymorphism and aggressive periodontitis. Zhonghua Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi 42:268–271

Babel N, Cherepnev G, Babel D, Tropmann A, Hammer M, Volk HD, Reinke P (2006) Analysis of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, transforming growth factor-beta, interleukin-10, IL-6, and interferon-gamma gene polymorphisms in patients with chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol 77:1978–1983

Folwaczny M, Glas J, Torok HP, Mende M, Folwaczny C (2004) Lack of association between the TNF alpha G −308 A promoter polymorphism and periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol 31:449–453

Fassmann A, Holla LI, Buckova D, Vasku A, Znojil V, Vanek J (2003) Polymorphisms in the +252(A/G) lymphotoxin-alpha and the −308(A/G) tumor necrosis factor-alpha genes and susceptibility to chronic periodontitis in a Czech population. J Periodontal Res 38:394–399

Soga Y, Nishimura F, Ohyama H, Maeda H, Takashiba S, Murayama Y (2003) Tumor necrosis factor-alpha gene (TNF-alpha)−1031/−863, −857 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are associated with severe adult periodontitis in Japanese. J Clin Periodontol 30:524–531

Craandijk J, van Krugten MV, Verweij CL, van der Velden U, Loos BG (2002) Tumor necrosis factor-alpha gene polymorphisms in relation to periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol 29:28–34

Endo M, Tai H, Tabeta K, Kobayashi T, Yamazaki K, Yoshie H (2001) Analysis of single nucleotide polymorphisms in the 5′-flanking region of tumor necrosis factor-alpha gene in Japanese patients with early-onset periodontitis. J Periodontol 72:1554–1559

Galbraith GM, Hendley TM, Sanders JJ, Palesch Y, Pandey JP (1999) Polymorphic cytokine genotypes as markers of disease severity in adult periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol 26:705–709

Fonseca JE, Santos MJ, Canhao H, Choy E (2009) Interleukin-6 as a key player in systemic inflammation and joint destruction. Autoimmun Rev 8:538–542

Morse HR, Olomolaiye OO, Wood NA, Keen LJ, Bidwell JL (1999) Induced heteroduplex genotyping of TNF-alpha, IL-1beta, IL-6 and IL-10 polymorphisms associated with transcriptional regulation. Cytokine 11:789–795

Hulkkonen J, Pertovaara M, Antonen J, Pasternack A, Hurme M (2001) Elevated interleukin-6 plasma levels are regulated by the promoter region polymorphism of the IL6 gene in primary Sjogren’s syndrome and correlate with the clinical manifestations of the disease. Rheumatology (Oxford) 40:656–661

Fishman D, Faulds G, Jeffery R, Mohamed-Ali V, Yudkin JS, Humphries S, Woo P (1998) The effect of novel polymorphisms in the interleukin-6 (IL-6) gene on IL-6 transcription and plasma IL-6 levels, and an association with systemic-onset juvenile chronic arthritis. J Clin Invest 102:1369–1376

Brull DJ, Montgomery HE, Sanders J, Dhamrait S, Luong L, Rumley A, Lowe GD, Humphries SE (2001) Interleukin-6 gene −174 g > c and −572 g > c promoter polymorphisms are strong predictors of plasma interleukin-6 levels after coronary artery bypass surgery. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 21:1458–1463

Panoulas VF, Stavropoulos-Kalinoglou A, Metsios GS, Smith JP, Milionis HJ, Douglas KM, Nightingale P, Kitas GD (2009) Association of interleukin-6 (IL-6) −174G/C gene polymorphism with cardiovascular disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: the role of obesity and smoking. Atherosclerosis 204:178–183

Lee YH, Lee HS, Choi SJ, Ji JD, Song GG (2012) The association between interleukin-6 polymorphisms and systemic lupus erythematosus: a meta-analysis. Lupus 21:60–7

Lee YH, Ji JD, Song GG (2007) Tumor necrosis factor-alpha promoter −308 A/G polymorphism and rheumatoid arthritis susceptibility: a metaanalysis. J Rheumatol 34:43–49

Lee YH, Rho YH, Choi SJ, Ji JD, Song GG (2006) Association of TNF-alpha −308 G/A polymorphism with responsiveness to TNF-alpha-blockers in rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis. Rheumatol Int 27:157–161. doi:10.1007/s00296-006-0175-7

Lee YH, Harley JB, Nath SK (2006) Meta-analysis of TNF-alpha promoter −308 A/G polymorphism and SLE susceptibility. Eur J Hum Genet 14:364–371

Lee YH, Song GG (2011) Efficacy and safety of monthly 150 mg oral ibandronate in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Korean J Intern Med 26:340–347

Davey Smith G, Egger M (1997) Meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. Lancet 350:1182

Egger M, Smith GD, Phillips AN (1997) Meta-analysis: principles and procedures. BMJ 315:1533–1537

DerSimonian R, Laird N (1986) Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 7:177–188

Higgins JP, Thompson SG (2002) Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 21:1539–1558

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C (1997) Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315:629–634

Kalburgi NB, Bhatia A, Bilichodmath S, Patil SR, Mangalekar SB, Bhat K (2010) Interleukin-6 promoter polymorphism (−174 G/C) in Indian patients with chronic periodontitis. J Oral Sci 52:431–437

Fan WH, Liu DL, Xiao LM, Xie CJ, Sun SY, Zhang JC (2010) Coronary heart disease and chronic periodontitis: is polymorphism of interleukin-6 gene the common risk factor in a Chinese population? Oral Dis 17:270–276

Franch-Chillida F, Nibali L, Madden I, Donos N, Brett P (2010) Association between interleukin-6 polymorphisms and periodontitis in Indian non-smokers. J Clin Periodontol 37:137–144

Xiao LM, Yan YX, Xie CJ, Fan WH, Xuan DY, Wang CX, Chen L, Sun SY, Xie BY, Zhang JC (2009) Association among interleukin-6 gene polymorphism, diabetes and periodontitis in a Chinese population. Oral Dis 15:547–553

Nibali L, D’Aiuto F, Donos N, Griffiths GS, Parkar M, Tonetti MS, Humphries SE, Brett PM (2009) Association between periodontitis and common variants in the promoter of the interleukin-6 gene. Cytokine 45:50–54

Tervonen T, Raunio T, Knuuttila M, Karttunen R (2007) Polymorphisms in the CD14 and IL-6 genes associated with periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol 34:377–383

Moreira PR, Lima PM, Sathler KO, Imanishi SA, Costa JE, Gomes RS, Gollob KJ, Dutra WO (2007) Interleukin-6 expression and gene polymorphism are associated with severity of periodontal disease in a sample of Brazilian individuals. Clin Exp Immunol 148:119–126

Jansson H, Lyssenko V, Gustavsson A, Hamberg K, Soderfeldt B, Groop L, Bratthall G (2006) Analysis of the interleukin-1 and interleukin-6 polymorphisms in patients with chronic periodontitis. A pilot study. Swed Dent J 30:17–23

Brett PM, Zygogianni P, Griffiths GS, Tomaz M, Parkar M, D’Aiuto F, Tonetti M (2005) Functional gene polymorphisms in aggressive and chronic periodontitis. J Dent Res 84:1149–1153

Holla LI, Fassmann A, Stejskalova A, Znojil V, Vanek J, Vacha J (2004) Analysis of the interleukin-6 gene promoter polymorphisms in Czech patients with chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol 75:30–36. doi:10.1902/jop.2004.75.1.30

Trevilatto PC, Scarel-Caminaga RM, de Brito RB Jr, de Souza AP, Line SR (2003) Polymorphism at position −174 of IL-6 gene is associated with susceptibility to chronic periodontitis in a Caucasian Brazilian population. J Clin Periodontol 30:438–442

Komatsu Y, Tai H, Galicia JC, Shimada Y, Endo M, Akazawa K, Yamazaki K, Yoshie H (2005) Interleukin-6 (IL-6)–373 A9T11 allele is associated with reduced susceptibility to chronic periodontitis in Japanese subjects and decreased serum IL-6 level. Tissue Antigens 65:110–114

Guan ZM, Liu JJ, Ma X, Wu DH, Yu J, Huang GQ (2008) Relationship between interleukin-6 gene−572C/G polymorphism and chronic periodontitis. Zhonghua Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi 43:410–413

Jingjin L, Zemin G, Xin M, Donghong W, Jianhua G, Jie Y, Yonggong W (2010) Correlation between an interleukin-6 −572C/G polymorphism and chronic periodontitis. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 30:301–305

Rodriguez-Carreon AA, Zuniga J, Hernandez-Pacheco G, Rodriguez-Perez JM, Perez-Hernandez N, Montes de Oca JV, Cardiel MH, Granados J, Vargas-Alarcon G (2005) Tumor necrosis factor-alpha −308 promoter polymorphism contributes independently to HLA alleles in the severity of rheumatoid arthritis in Mexicans. J Autoimmun 24:63–68

Baena A, Leung JY, Sullivan AD, Landires I, Vasquez-Luna N, Quinones-Berrocal J, Fraser PA, Uko GP, Delgado JC, Clavijo OP, Thim S, Meshnick SR, Nyirenda T, Yunis EJ, Goldfeld AE (2002) TNF-alpha promoter single nucleotide polymorphisms are markers of human ancestry. Genes Immun 3:482–487

Shao MY, Huang P, Cheng R, Hu T (2009) Interleukin-6 polymorphisms modify the risk of periodontitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B 10:920–927

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a Korea University Grant.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no potential conflict of interest to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Song, G.G., Choi, S.J., Ji, J.D. et al. Association between tumor necrosis factor-α promoter −308 A/G, −238 A/G, interleukin-6 −174 G/C and −572 G/C polymorphisms and periodontal disease: a meta-analysis. Mol Biol Rep 40, 5191–5203 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-013-2621-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-013-2621-4