Abstract

Few studies have examined how changes in materialism relate to changes in well-being; fewer have experimentally manipulated materialism to change well-being. Studies 1, 2, and 3 examined how changes in materialistic aspirations related to changes in well-being, using varying time frames (12 years, 2 years, and 6 months), samples (US young adults and Icelandic adults), and measures of materialism and well-being. Across all three studies, results supported the hypothesis that people’s well-being improves as they place relatively less importance on materialistic goals and values, whereas orienting toward materialistic goals relatively more is associated with decreases in well-being over time. Study 2 additionally demonstrated that this association was mediated by changes in psychological need satisfaction. A fourth, experimental study showed that highly materialistic US adolescents who received an intervention that decreased materialism also experienced increases in self-esteem over the next several months, relative to a control group. Thus, well-being changes as people change their relative focus on materialistic goals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Individuals living in contemporary Western industrialized nations, as well as many other parts of the world, are frequently exposed to messages propounding materialism, the belief that, compared to other goals one might pursue, it is important and valuable to prioritize the goal of attaining money and having many possessions (Kasser 2002; Richins and Dawson 1992). While believing in the relative importance of such materialistic goals may help to maintain capitalist economic organizations and consumer cultural systems (Kasser et al. 2007), the relative prioritization of such goals is also associated with costs for people’s psychological well-being. Starting in the mid-1980s and early 1990s (Belk 1985; Kasser and Ryan 1993; Richins and Dawson 1992), empirical evidence began to accumulate showing that the more that people prioritized values and goals for money and possessions, relative to other aims in life, the lower they scored on outcomes such as life satisfaction, happiness, vitality, and self-actualization, and the higher they scored on outcomes such as depression, anxiety, behavior disorders, and a host of other types of psychopathology (see Kasser 2002, for a review). Since this early research, dozens of other studies have conceptually replicated these findings with children (Banerjee and Dittmar 2008; Kasser 2005; Schor 2004), college students (e.g., Christopher et al. 2007), and adults (e.g., Burroughs and Rindfleisch 2002), with business students and entrepreneurs (Kasser and Ahuvia 2002; Srivastava et al. 2001), and in various nations around the world (e.g., Kim et al. 2003; Martos and Kopp 2012; Romero et al. 2011; Ryan et al. 1999). Indeed, an on-going meta-analysis of over 200 independent samples revealed that the negative association between materialism and well-being is robust across different operationalizations of the constructsFootnote 1 and across different personal and cultural characteristics (Dittmar et al. 2013).

While the literature on how well-being relates to people’s relative prioritization of materialistic goals has moved into a fairly mature stage, this body of empirical research suffers from one of the same basic methodological limitations as does much other research investigating relationships between well-being and any number of other motivational variables: Most of the data comes from cross-sectional, correlational studies in which participants completed measures of the relevant constructs at only one point in time. Only a handful of longitudinal and experimental studies have examined how changes in well-being are associated with naturally occurring changes in materialism or with experimental manipulations of the concern for money and possessions.

Two longitudinal studies have studied how changes in a broader array of extrinsic goals (i.e., for image and popularity, in addition to money and possessions) are related to changes in well-being. Sheldon (2005) followed US undergraduates from their first to fourth years of college, finding that changes in the relative importance they placed on a summary measure of extrinsic goals were not significantly related to reported changes in well-being. Niemiec et al. (2009) showed that over the course of a year, increased relative attainment of extrinsic goals failed to provide well-being benefits, as progress at such goals did not promote greater satisfaction of psychological needs.Footnote 2

Two other relevant longitudinal studies have used a cohort approach, examining how changes in nation-level indices of materialism and well-being co-vary from year to year. Hellevik (2003) correlated yearly measures of well-being in Norway with the extent to which citizens espoused strong materialistic values each year, finding that the two were negatively associated. Similarly, Twenge et al. (2010) reported that the priority US adolescents placed on materialistic aims in a particular year was positively associated with yearly levels of adolescent psychopathology (as assessed by the MMPI). While these studies are clearly provocative, one must of course take care in generalizing findings at the level of a cohort to the level of individual people.

The evidence from experimental studies is also rather lean and somewhat mixed. Although one study found that increases in depressive and anxious affect resulted from viewing images of high-end consumer products (Bauer et al. 2012), two other studies found that brief writing and categorization exercises designed to increase materialistic concerns failed to affect participants’ mood (Solberg et al. 2004). While such evidence suggests that short-term manipulations of materialism may momentarily affect people’s emotional state, it remains unclear whether such effects are strong and endure beyond the laboratory.

The present studies

Given this rather small and contradictory literature, we conducted four studies to longitudinally examine how individual changes in well-being may be related to individual changes in the priority placed on materialistic values and goals. The first three studies tested the hypothesis that declines (or increases) in materialism are associated with increases (or declines) in well-being; these studies were conducted over different time spans (12 years, 2 years, and 6 months), in different cultures (the USA and Iceland), with different age groups (late adolescents and adults), and with different operationalizations of materialism (Likert-type surveys and relative centrality measures of financial success goals) and of well-being (psychopathology, life satisfaction, and affect). The first two studies examined naturally-occurring changes in materialism and well-being as late adolescents moved into young adulthood. Further, Study 2 tested whether the relationship between changes in materialistic priorities and changes in well-being is mediated by changes in psychological need satisfaction, as has been suggested by some theoretical (Deci and Ryan 2000; Kasser 2002) and empirical (Niemiec et al. 2009) work. Study 3 examined our basic hypothesis in the context of a societal-wide economic collapse, as past research (Abramson and Inglehart 1995; Sheldon and Kasser 2008) suggests that such threats may lead many people (but not necessarily all; see Kasser 2009) to orient more strongly towards materialistic goals, perhaps to the detriment of their well-being.

In all three of these studies we used a regression strategy to test our hypothesis that changes in materialism would be associated with changes in well-being. To this end, we regressed well-being scores onto: (a) measures of materialism and well-being assessed at an earlier time point; and then (b) a measure of materialism assessed at the same time as the well-being outcome. Support for our hypotheses would be forthcoming if the regression coefficient at the second step was significant, as this coefficient represents the extent to which changes in materialism are associated with changes in well-being (see Finkel 1995 for an overview and Sheldon et al. 2010 or Sheldon and Gunz 2009, Study 3, for previous articles using this approach). Importantly, we made no hypotheses about whether materialism assessed at an earlier time point would be associated with changes in well-being over time (i.e., the regression coefficient for materialism in the first step of the regression). We made no such hypotheses because our theoretical perspective suggests that individuals who share a particular materialism score at a particular time point might well diverge in the trajectory of their later materialism scores, with some increasing in materialism, some decreasing, and some remaining the same. As such, there would be no reason to predict that materialism assessed at a particular time point would relate in any systematic way to changes in well-being from that time point to some later time point. Instead, well-being would only be expected to change as the priority placed on materialistic values and goals also changed.

While Studies 1, 2, and 3 are longitudinal in design, their correlational nature nonetheless makes it impossible to reach conclusions about whether changes in materialism cause changes in well-being, changes in well-being cause changes in materialism, or changes in some third variable cause changes in both materialism and well-being. For this reason, in Study 4, we conducted an experiment in which adolescents and their parents were randomly assigned to either a no-treatment control group or to a three-session intervention designed to decrease the adolescents’ concern with materialistic aims in life. Adolescents’ well-being and materialism were assessed at baseline and twice again over the several months following the intervention. Using latent growth curve analyses, we then examined whether, compared to individuals in a control group, individuals who began the study high in materialism and received the intervention would experience increases in their well-being that persisted for some time after the intervention had ended. If results were consistent with this hypothesis, support would be obtained for the possibility that changes in materialism might play a causal role in changing well-being.

Study 1

Study 1 reports a 12-year longitudinal study of a heterogeneous group of US late adolescents/early adults, many of whom were at risk for developing psychopathology. We hypothesized that decreases (or increases) in the relative importance of materialistic aspirations from age 18 to 30 years would be associated with improvements (or declines) in mental health.

Method

Participants

Our sample consisted of 118 life-long participants in the Rochester Longitudinal Study who completed a measure of goals (see below) at both ages 18 and 30 years.Footnote 3 Participants entered the study in utero, their mothers having been recruited while pregnant with the target children. The children were then assessed on a variety of measures several times between birth and age 4 years, again at 13 and 18 years, and most recently at 30 years. Information collected at the last two time points provided the data for the present study. Participants received honoraria for completing interviews at both 18 and 30 years.

The initial sample intentionally over-represented individuals who were at high-risk for developing psychopathology, as approximately half of the mothers had a psychiatric diagnosis while pregnant with the target child, approximately 2/3 of the sample was from lower socio-economic strata, and approximately 1/3 was minority (primarily African-American). See Sameroff et al. (1982) for information about the initial recruitment of the sample.

The 118 individuals in this 30-year-old sample were 46.6 % male and 75.2 % Caucasian. Current educational status varied substantially, as 12.7 % of the sample had neither completed high school nor received a GED, whereas 9.3 % had a master’s level education or higher. Family income also ranged widely, as 13.8 % of the sample had an annual household income below $20,000, whereas 12.9 % earned over $100,000.

Measures

Materialism

Our measure of materialism at ages 18 and 30 was based on the Aspiration Index (AI). This measure, originally developed by Kasser and Ryan (1993), presented individuals with a variety of goals they might have for the future, asking them to rate the importance of each goal. Somewhat different versions were used at ages 18 and 30 years.

At age 18 years, most participants completed the AI in the context of an hour-long interview with the first author, although some completed it via a survey packet sent to their homes. Participants rated the importance of 30 goals on a 4-point scale, from 1 (not at all important) to 4 (very important). In addition to financial success aspirations (3 items, e.g., “You will have a job that pays well”; “You will have a job with high social status”), goals for self-acceptance, affiliation, and community feeling were also assessed. Cronbach’s α was .75 for the financial success domain, which was of primary interest in this study.

At age 30, respondents completed the AI in the context of an hour-long phone interview, again with the first author. They once again rated the importance of 30 aspirations, with the interviewer reading each item aloud and the participant providing his/her rating of the importance of each. This AI differed in several respects from the one completed at age 18 years. First, many items were reworded, others were dropped, and all items were worded in the first person rather than in the second person. Second, in addition to the four domains assessed at age 18, aspirations for image and spirituality were also assessed, although they were not included in the computation of materialism described below because they were not collected at age 18 years. Third, responses were made on a 1 (not at all) to 5 (very important) scale, as a midpoint of 3 (so/so) was added. Fourth, five items were used to assess each of the six aspiration domains, with additional items derived from Kasser and Ryan (1996). Sample items for the financial success domain include “I will be financially successful” and “I will have many expensive possessions.” Cronbach’s α for financial success importance at age 30 years was .70.

To obtain parallel measures of materialism at the two time points, two steps were taken. First, because the goals were rated on different scales at ages 18 and 30, we multiplied the 18-year-old ratings by five and the 30-year-old ratings by four to equate them. Second, because it is widely accepted among value and goal-system researchers that the relative importance of a value or goal is the most informative measure to use when assessing the extent to which individuals care about particular aims in life (Rokeach 1973; Schwartz 1992; see also Footnote 1), we created scores representing the relative importance of financial success aspirations at each age by subtracting each participant’s grand mean (i.e., the average importance ratings of financial success, self-acceptance, affiliation, and community feeling goals) from his/her average for financial success aspirations. This score thus represents how important financial success aspirations are to a person within the context of that individual’s system of goals; positive scores indicate caring about financial success relatively more than most other goals, and negative scores indicate caring about financial success relatively less than most other goals. One hundred eighteen observations were available for this measure of materialism.

Mental health problems

When participants were 18 years old, an experienced clinician interviewed them using the Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents, Version R-A (DICA; Herjanic and Reich 1982), which assesses DSM-III-R criteria for a wide variety of problems common during adolescence, including externalizing disorders (e.g., oppositional-defiant disorder and conduct disorder); substance abuse (e.g., the use of alcohol, cigarettes, and street drugs); mood disorders (e.g., major depression, mania); anxiety disorders (e.g., separation anxiety and obsessive–compulsive disorders); eating disorders (e.g., anorexia, bulimia); gender identity problems; somatization; and psychotic thinking. For each of the disorders assessed on the DICA, a score was computed reflecting the number of questions relevant to a particular diagnosis on which the participant responded positively. These scores were then summed across the different diagnostic categories to obtain a total mental health problems score at age 18 years.

Two sources of data were used to obtain a parallel, broad-band measure of mental health at age 30 years. First, participants completed the 90 item Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL-90; Derogatis et al. 1976), rating on a 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely) scale how much over the last 12 months they had been bothered by symptoms relevant to somatization, obsessive–compulsive disorder, interpersonal problems, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobias, paranoia, and psychotic thinking, in addition to a variety of other problems. The HSCL-90 was completed in a packet of surveys mailed to each participant’s home after the completion of two phone interviews. Because the HSCL-90 does not assess drug abuse (which had been included on the DICA at age 18), we supplemented it with nine items that assessed how often participants had used alcohol, cigarettes, marijuana, LSD, other psychedelics, and cocaine during the past year. All 99 of these items were z-scored and then averaged to obtain a measure of mental health problems at age 30 years. High scores indicate more mental health problems (i.e., lower psychological well-being).

Results

Attrition analyses

Attrition analyses examined whether the 118 individuals who completed the Aspiration Index at age 30 years differed from the 30 individuals who completed the Aspiration Index at age 18 years but not at age 30 years. There were no significant differences between these two groups for either the 18-year-old ratings of mental health problems or the relative importance of financial success aspirations. Analyses of demographic factors suggested, however, that males (p = .02), African-Americans (p = .001), and individuals from lower socio-economic strata (p < .001) were especially likely to drop out of the study from age 18 to 30 years. Thus, although these results suggested that the sample did not experience differential attrition on the variables of primary interest to this study, it did become more female, more Caucasian, and more affluent.

Inter-correlations of primary study variables

As reported in Table 1, moderate stability over the 12 years separating assessments was noted for both the relative importance of financial success aspirations and for mental health problems. Replicating past research at the cross-sectional level, the relative importance of financial success aspirations was positively associated with mental health problems, marginally so at 18-years-old and significantly so at 30-years-old. Cross-correlations were not significant; that is, 18-year old materialism was unrelated to 30-year-old mental health problems, and 18-year-old mental health was unrelated to 30-year-old materialism.

We also compared mean scores for the relative importance of financial success aspirations at age 18 and 30 years. This analysis revealed an overall tendency for individuals to place relatively less importance on financial success as they aged (t(117) = −5.91, p < .01). This finding should be treated with caution, however, since non-identical measures were used at the two time points.

Testing the longitudinal hypothesis

As described in the introduction, regression analyses were used to explore potential associations between changes in individuals’ orientation towards materialism and changes in their mental health from age 18 to 30 years. At Step 1, participants’ mental health at age 30 years was regressed onto their mental health at age 18 years and the relative importance they placed on financial success aspirations at age 18 years; at Step 2, we entered the 30-year-old relative importance of financial success aspirations score. This regression coefficient from Step 2 provided the key test of our hypothesis that changes in materialism relate to changes in well-being. Ninety-nine participants had complete data for these analyses.

After controlling for 18-year-old mental health problems (β = .46, p < .01) and 18-year-old relative importance of financial success aspirations (β = .01, ns), the 30-year-old relative importance of financial success aspirations was significantly positively associated with 30-year-old mental health problems (β = .21, p < .05).Footnote 4 Thus, as predicted, individuals whose goal systems became relatively less oriented toward the goal of financial success experienced a decrease in mental health problems, whereas individuals whose goal systems became relatively more oriented toward financial success experienced increased mental health problems. This finding was unchanged after controlling for annual household income at age 30; the β did drop slightly (β = .20, p = .054) after controlling for gender.

Brief discussion

The results of Study 1 showed that to the extent individuals placed relatively less importance on financial success goals between age 18 and age 30 years, their mental health improved, whereas to the extent such goals became relatively more important, their mental health declined. In contrast, the relative importance people placed on materialistic goals when they were 18-years-old bore no relationships with changes they experienced in mental health over the next 12 years. As we had predicted, changes in mental health were associated with changes in people’s orientation towards materialistic goals, not with their initial orientation towards materialistic goals.

Study 2

Given these promising findings, we attempted to replicate them in a second, shorter longitudinal study that followed college seniors for 2 years as they transitioned into their adult lives. Study 2 also addressed four limitations of Study 1. First, Study 1’s sample size was rather low, so we recruited a somewhat larger sample in Study 2. Second, Study 1 participants completed somewhat different measures of materialism and psychological well-being at the two time points, leaving open the possibility that observed associations were due to these different versions of the scales, rather than to actual changes; in Study 2, we therefore administered identical measures at both time points. Third, Study 1’s measures of well-being were limited to those assessing psychopathology, so in Study 2 we assessed subjective well-being (SWB) to address the methodological generalizability of Study 1’s findings.

Fourth, in Study 2 we examined whether changes in the satisfaction of autonomy, competence, and relatedness needs would mediate any observed associations between changes in the relative importance placed on the aspiration of financial success and changes in well-being. Past research has shown that experimental manipulations that focus people on the pursuit of need-satisfying goals yield increases in happiness (Sheldon et al. 2010). Further, materialism researchers in the self-determination theory tradition (e.g., Deci and Ryan 2000; Kasser 2002) have suggested that materialistic values are associated with relatively low levels of well-being because such values lead individuals to experience relatively low levels of satisfaction of the psychological needs necessary for optimal health and thriving, a finding supported in one longitudinal study of extrinsic goal attainment (Niemiec et al. 2009).

Method

Participants

Participants were 251 (84 male, 156 female, and 11 who did not indicate gender) seniors at either a private northeastern US university or a midwestern US 4-year college who completed Time 1 surveys shortly before they graduated from college and who gave permission for us to contact them after graduation so as to administer surveys on their functioning during post-college life.Footnote 5 Participants were contacted again 1 year later (Time 2), although those data were not relevant to the current analyses. Our focus in this study was on the 147 participants who completed and returned their surveys 2 years after graduating (Time 3). Most participants were Caucasian (79.9 %), and the rest were Asian (9.8 %), African American (4.9 %), Hispanic (4.1 %), and “Other” (1.2 %); two participants did not indicate their ethnic background. At T3, participants reported their annual personal income on a 7-point scale: 22 % were earning less than $15 K, 43 % were earning between $15 K and $30 K, 26 % were earning between $30 K and $50 K, and 9 % were earning over $50 K. All participants were volunteers and received no compensation.

Measures

Materialism

This study used a 35-item Aspiration Index (based on Kasser and Ryan 1996) that assessed materialistic aspirations (e.g., “to be a wealthy person”, “to have many expensive possessions”) in the context of six other aspiration domains (self-acceptance, affiliation, community feeling, physical health, popularity, and image); each of the seven domains was represented by five items. Participants reported how important they viewed each aspiration at Time 1 and at Time 3 on a 7-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much). The reliabilities for financial success aspirations were .89 and .88 at Times 1 and 3, respectively. As in Study 1, we created scores representing the relative importance placed on financial success aspirations by first computing an overall importance score for each participant at both Times 1 and 3, regardless of content, averaging now across seven domains of aspirations. We then subtracted the overall importance score from the importance placed on financial success aspirations at the corresponding time. High scores thus represent a stronger relative materialistic value orientation.

Subjective well-being

We assessed the three standard components of SWB (Diener 1984) by asking participants to complete measures of life satisfaction, positive affect, and negative affect. Specifically, the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Pavot et al. 1998) assessed life satisfaction (5 items; e.g., “The conditions of my life are excellent”; αs = .86 at Time 1 and .87 at Time 3). Responses were made on a 7-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The Positive Affect Negative Affect Scale (PANAS; Watson et al. 1988) assessed positive emotions (10 items; e.g., “excited”; αs = .91 at both Times 1 and 3) and negative emotions (10 items; e.g., “upset”; αs = .90 and .91 at Times 1 and 3, respectively). Responses were made on a 7-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much). We created SWB composites at Times 1 and 3 by standardizing participants’ scores on life satisfaction, positive affect, and negative affect, and subtracting negative affect from the sum of life satisfaction and positive affect. This procedure is justified given both its use in past research (e.g., Sheldon and Niemiec 2006), as well as the inter-correlations among these three SWB indicators in the present study (i.e., rs between |.34| and |.56| at T1 and between |.22| and |.61| at T3, all ps < .01). High scores indicate greater well-being.

Psychological need satisfaction

The 21-item Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction Scale-General (e.g., Gagné 2003) assessed satisfaction of the needs for autonomy (7 items; e.g., “I feel like I can pretty much be myself in my daily situations”; α = .68 at Time 1 and α = .73 at Time 3), competence (6 items; e.g., “Most days I feel a sense of accomplishment from what I do”; α = .74 at Time 1 and α = .73 at Time 3), and relatedness (8 items; e.g., “People are generally pretty friendly towards me”; α = .80 at Time 1 and α = .83 at Time 3). Responses were made on a 7-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 7 (very true). In order to simplify mediational analyses, and because we had made no hypotheses about how changes in any particular need would mediate associations between changes in materialism and changes in SWB, we combined the three need satisfaction scores at both T1 and T3. Such a strategy is justified by the inter-correlations of these three measures, both at T1 (rs between .42 and .53, ps < .001) and at T3 (rs between .56 and .58, ps < .001). High scores indicate greater need satisfaction.

Results

Attrition analyses

Attrition analyses were used to determine whether the 147 participants who provided data at Times 1 and 3 differed from the 104 participants who provided data at Time 1 only. There were no significant differences on gender, the Time 1 measures of the relative importance of financial success aspirations or the Time 1 measures of need satisfaction. However, participants who provided data at Time 3 reported higher SWB at Time 1 than did those who provided data at Time 1 only (t(240) = −2.17, p < .05). Thus, participants who continued in the study had higher well-being than did those who dropped out over the course of the 2 years.

Inter-correlations of primary study variables

As reported in Table 2, relatively high stability over the 2 years separating assessments in Study 2 was noted for the relative importance of financial success aspirations, for SWB, and for need satisfaction. At T1, the relative importance of financial success aspirations was, surprisingly, uncorrelated with either need satisfaction or well-being; these latter two measures were significantly positively correlated with each other, however. T3 correlations were more consistent with past research, as the relative importance of financial success aspirations was associated with significantly lower levels of both need satisfaction and well-being; need satisfaction and well-being were once again significantly positively correlated with each other.

Cross-correlations showed a rather mixed pattern in Study 2. T1 Materialism was significantly negatively correlated with T3 SWB but uncorrelated with T3 Need Satisfaction; T3 Materialism was not correlated with either T1 SWB or T1 Need Satisfaction. T1 SWB was not correlated with T3 Materialism but was positively correlated with T3 Need Satisfaction; T3 SWB was negatively correlated with T1 Materialism and positively correlated with T1 Need Satisfaction. T1 Need Satisfaction was uncorrelated with T3 Materialism but positively correlated with T3 SWB; T3 Need Satisfaction was uncorrelated with T1 Materialism but positively correlated with T1 SWB.

In contrast to Study 1, no overall mean level changes in the relative importance participants placed on financial success were observed (T1 M = −1.35, SD = 1.22; T3 M = −1.25, SD = 1.07; t(142) = −1.75, ns).

Testing the longitudinal and mediational hypotheses

Next we tested whether changes in psychological well-being from Time 1 to Time 3 were associated with changes in the relative importance participants placed on financial success aspirations during that time period. We followed the same analytic strategy as in Study 1. At Step 1 SWB at Time 3 was regressed onto SWB at Time 1 and the T1 relative importance of financial success aspirations score. Both were significantly associated with T3 SWB (βs = .63, p < .001 and −.13, p < .05, respectively). Then, we entered the T3 relative importance of financial success aspirations score to test our primary hypothesis. As predicted, increases in the relative priority placed on financial success aspirations were associated with decreases in SWB (β = −.22, p < .05).Footnote 6 Results were unchanged when Time 3 income was entered as a covariate at Step 1, and were slightly weaker when Gender was entered at Step 1 (β = −.21, p = .066).

We then tested whether this relation between changes in materialism and changes in SWB was mediated by changes in need satisfaction. Using the well-known criteria for mediation outlined by Baron and Kenny (1986), change in the relative importance of financial success aspirations was the predictor, change in well-being was the outcome, and change in need satisfaction was the proposed mediator. As reported above, increases in the relative importance placed on financial success aspirations from T1 to T3 were associated with decreases in SWB (β = −.22, p < .05). Further, people who became more focused on financial success from T1 to T3 also experienced significant declines in their need satisfaction over that time period (β = −.31, p < .01). Finally, the crucial test of our mediational hypothesis involved examining the results of a regression analysis in which changes in the relative importance placed on financial success and changes in need satisfaction were entered as simultaneous predictors of changes in SWB. As expected, changes in need satisfaction remained significant (β = .63, p < .001) whereas the effect of changes in the relative importance placed on financial success aspirations was reduced from β = −.22 (p < .05) to β = .00 (ns). To test whether the mediation was significant, we used the procedure outlined by MacKinnon et al. (2002). As expected, the z′ test indicated that change in basic psychological need satisfaction was a significant mediator of the relation between change in the relative importance of financial success aspirations and change in SWB (z′ = −2.59, p < .01). Results remained essentially the same when Time 3 income was entered as a covariate at Step 1.

Brief discussion

In contrast to Study 1, results of Study 2 revealed that shifts in well-being over 2 years were predictable on the basis of initial materialism measures, with those individuals scoring relatively high in materialism during their senior year of college reporting greater decrements in well-being over the next 2 years. In addition, as was the case in Study 1, and as we had predicted, the results of Study 2 showed that to the extent individuals decreased the relative importance they placed on goals for financial success and possessions, their well-being improved over time. Moreover, theoretical propositions (Deci and Ryan 2000; Kasser 2002) explaining this association were supported, as mediational analyses showed that to the extent individuals became relatively less (or more) oriented towards materialistic aspirations over a 2-year period, they reported increased (or decreased) satisfaction of their psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness, and this increase (or decrease) in need satisfaction fully accounted for the reported increase (or decrease) in well-being. Such results are consistent with the theoretical proposition that when people become less focused on attaining money and possessions, they feel more autonomous, competent, and related to others, and these experiences of psychological need satisfaction are associated with improved well-being, whereas an increased orientation towards materialistic aims is associated with declines in need satisfaction, and declines in well-being.

Study 3

Rather than re-examining our hypotheses in the context of the normative development of young adults, our third study was conducted in a cultural context and situation that might be expected to cause many participants to increase the priority they place on materialistic aspirations: the collapse of a society’s economy. Among the known causes of a strong endorsement of materialistic values is economic insecurity, as children who grow up in poor families (Cohen and Cohen 1996; Kasser et al. 1995) or in economically difficult times (Abramson and Inglehart 1995) tend to place relatively more importance on financial success and wealth. What’s more, one experimental study documents that college students place stronger priority on extrinsic (relative to intrinsic) aspirations after being asked to imagine graduating during an economic recession than during economically-healthy times (Sheldon and Kasser 2008). Such findings suggest that economic difficulties are likely to lead people to place relatively higher importance on financial success aspirations, which may then be associated with declines in their well-being.

We therefore conducted Study 3 in Iceland, where these types of economic disruptions recently occurred. In 2007 Iceland was the fifth richest nation in the world (measured by Gross Domestic Product per capita; OECD 2008), but the 2008 global economic crisis led the nation to quickly plummet into economic recession. Compared to other economically-developed nations, the Icelandic recession was particularly unique and extreme due to the fact that the bank system had expanded out of proportion for a country with such a small population (approximately 300,000 people), so that when the banking system crashed, it became very difficult for the government to assume banks’ huge debts. Nevertheless, in October 2009, all Icelandic banks were nationalised, leaving the country with debts 200 % greater than its GDP (visir.is 2009). Taking on this debt burden left Iceland on the verge of bankruptcy and the government had to appeal for help to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Thus, the Icelandic recession can be classified as an economic crash rather than an economic crisis (or even a Great Recession).

Iceland’s economic crash offers a particularly interesting context for our research because such upheaval should be a time when people are questioning their goals, particularly goals concerning money and material goods, which had been strong in Iceland (Garðarsdóttir et al. 2009). Thus, such a situation should be conducive to shifts in goals, even over a relatively short time period such as 6 months. Past research reviewed above would suggest that a significant portion of citizens would likely respond to the desperate economic climate with an increased relative focus on materialistic aims, given the psychological insecurity the situation would cause. At the same time, however, some people respond to such feelings of insecurity with a movement away from materialistic aims (Kasser 2009). The possibility that some individuals may respond with a relative de-prioritization of financial success aspirations may have been facilitated by the fact that, during the crisis, the Icelandic government called for a return to family and community (i.e., intrinsic) values, as well as a reduction of the materialistic value orientation that had become so strong in Iceland (mbl.is 2009). [The fact that some people did become relatively less materialistic was reflected in some respondents’ open-ended comments, such as “Before we wanted to be entrepreneurs, now we just want to be good people” (Árnadóttir et al. 2010)].

In sum, although we expected to observe a general shift towards materialistic aims in Iceland during this period, there was likely enough variance in people’s responses to the economic crisis to test our primary hypothesis that increases in materialism over time would be accompanied by decreases in well-being, whereas decreasing one’s focus on materialistic goals would be associated with improvements in one’s well-being.

Method

Participants

In February 2009, the first time point, 748 Icelandic participants completed our online questionnaire. Six months later, in July 2009, 515 people completed the same questionnaire a second time, yielding a retention rate of 70.5 %. The final T2 sample was 70 % female and 100 % Caucasian. Participants reported their highest educational attainment; only 4 % of the sample had not completed high school whereas 76 % had completed an undergraduate or post-graduate education. At Time 2, participants also reported in an open-ended fashion on their monthly income, which was then converted from Icelandic Cronas into yearly $USD; 20 % of the sample had an annual household income below $20,000 USD, whereas 14 % reported an annual household income over $100,000 USD. Thus, compared to the general population of Icelanders, our sample was more female and Caucasian, and was also wealthier and better educated.

Measures

All surveys were translated from English into Icelandic using established back-translation procedures (Brislin 1970).

Materialism

Materialistic values were assessed with the Materialistic Values Scale (MVS; Richins 2004), which assessed the importance ascribed to the ownership and acquisition of material goods in achieving major life goals. The MVS is widely used, particularly in consumer research, is well-validated, and has good reliability and inter-item consistency (Richins 2004). The MVS has 15 items (e.g., “I admire people who own expensive homes, cars, and clothes,” “Buying things gives me a lot of pleasure,” and “I’d be happier if I could afford to buy more things”) that are rated on a scale ranging from 1 (disagree strongly) to 6 (agree strongly). Internal consistency was excellent at both T1 (α = .80) and T2 (α = .81).

Subjective well-being

As in Study 2, we assessed SWB by measuring participants’ evaluation of life satisfaction as well as the prominence of positive affective states relative to negative affective states. Participants completed the five-item Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al. 1985), supplemented by two items assessing how typical it was for respondents to experience positive and negative emotions (Garðarsdóttir et al. 2009). The scale format ranged from 1 (disagree strongly) to 6 (agree strongly). The life satisfaction, positive affect, and negative affect variables were all significantly correlated with each other at T1 (rs ranging between |.32| and |.87|, ps < .001) and at T2 (rs ranging between |.31| and |.89|, ps < .001). We therefore created a summary SWB variables by averaging together the five life satisfaction items, and then averaging this summary score with participants’ report on positive and (reversed) negative emotions.

Results

Attrition analyses

We conducted a MANOVA on the primary study variables and demographics to examine whether there were systematic differences between the 515 respondents who completed both T1 and T2 measures and the 233 respondents who dropped out by T2. There was no evidence of systematic differences at the multivariate level, F (14, 733) = 1.49, ns. However, one univariate difference emerged: those who dropped out of the study between T1 and T2 were more materialistic than those who stayed in the study, F (1, 746) = 6.19, p < .05.

Inter-correlations of primary study variables

As reported in Table 3, moderate stability over the 6 months separating assessments was noted for both the relative importance of financial success aspirations and for SWB. Replicating past research at the cross-sectional level, materialism was significantly negatively correlated with SWB at both T1 and T2. Cross-correlations were both significant; that is, T1 Materialism was significantly negatively associated with T2 SWB, and T1 SWB was significantly negatively correlated with T2 Materialism.

Participants also reported significantly higher MVS scores at T2 (Mean = 2.58, SD = 0.57) than at T1 (Mean = 2.39, SD = 0.68), t (515) = −5.40, p < .001). This finding is consistent with past studies demonstrating the influence of economic insecurity on materialistic values (Abramson and Inglehart 1995; Sheldon and Kasser 2008), but the relatively small size of the effect (d = .23) suggests that enough variability existed in the sample to test our primary hypotheses.

Testing the longitudinal hypothesis

As in the previous studies, we used regression analyses to examine changes in SWB over time as they related to changes in materialism. After controlling for the relations of T1 SWB (β = .65, p < .001) and T1 endorsement of materialism (β = .21, p < .001), respondents’ materialism scores at T2 were significantly negatively associated with T2 SWB (β = −.30, p < .001). Thus, in contrast to the previous two studies, T1 Materialism was positively related to changes in well-being over time in this study. More importantly for our predictions, however, the regression coefficient at Step 2 revealed that individuals who became less oriented toward materialism over time experienced an increase in SWB, whereas those who became more oriented toward materialism decreased in SWB. Additional analyses revealed that this finding remained unchanged even when age, gender, or T2 income of the participant was entered at Step 1 of the regression.

Brief discussion

Study 3 examined our primary hypothesis in the context of the 2008 economic collapse of Iceland. As would be predicted based on past studies on materialism and economic insecurity (e.g., Sheldon and Kasser 2008), over a 6 month period following the onset of their nation’s economic difficulties, a significant majority of Icelandic respondents placed increasing priority on materialistic concerns. Consistent with our primary hypothesis, the changes in materialism (assumedly brought on in part by the economic collapse) were associated with changes in well-being, such that to the extent respondents decreased their orientation towards materialism, they experienced increases in SWB, whereas to the extent they increased in materialism, they reported decreases in SWB.

The analyses examining the associations of T1 Materialism with changes in well-being stand in contrast to the results of both Study 1 and Study 2. Whereas Study 1 found that initial materialism was unrelated to changes in mental health, and Study 2 found that initial materialism was related to decrements in well-being over time, Study 3 found that initial materialism was related to increases in well-being over time. We interpret this inconsistent pattern of findings as evidence for the logic we described in the introduction: Changes in well-being are not consistently predictable on the basis of initial measures of materialism. This inconsistent set of findings stands in contrast to the consistent pattern of results obtained when changes in materialism were associated with changes in well-being.

Three weaknesses of Study 3 should be noted. First, our sample participants were wealthier and better-educated than the Icelandic population as a whole; perhaps results would have differed if more individuals who were less financially well-off were included in the sample. Second, we were unable to examine in a systematic way the interesting question of whether individual differences in the extent to which people were personally affected by the economic collapse influenced the pattern of results reported here; perhaps those more affected by the economic collapse engaged in dissonance-reduction mechanisms (i.e., “I’ve lost my savings; wealth isn’t all that important anyway”) which protected their well-being. Third, the meaning of materialism may have changed for participants in the context of the economic collapse, and thereby influenced the results. For example, Grouzet et al. (2005) found that financial success aspirations were more closely associated with aspirations for image and popularity among wealthy nations, but were more associated with physical health and safety aspirations in poorer nations. Perhaps, then, these Icelandic participants came to see materialism as being less about status and more about survival as the economic collapse unfolded, and this explained why increasing materialism predicted lower SWB. Future studies utilizing sensitive assessments of such constructs could examine this possibility.

Study 4

While the three studies reported thus far had longitudinal designs, conceptually replicated previous cross-sectional findings, and supported our predictions, they were all correlational in nature, leaving the causal relationships between the variables unclear. While the results of the regressions reported in Studies 1, 2, and 3 support the idea that changes in materialism predict changes in well-being, the quite reasonable idea that changes in well-being lead to changes in materialism is also supported by some ancillary analyses we conducted. In each study, we ran additional regression analyses that paralleled those reported in the Results sections, but instead we regressed Materialism measures onto the initial assessments of SWB and Materialism (at Step 1) and then examined the β of the SWB measure (at Step 2) that had been assessed at the same time as the outcome Materialism measure; such a procedure tests how changes in well-being predict changes in materialism. In each regression, the β at Step 2 was significant or marginally significant, although somewhat weaker than the βs previously reported in the Results sections of Studies 1, 2, and 3. Specifically, in Study 1, T2 SWB β = .17 (p = .08) versus β = .21 reported earlier for T2 Materialism; in Study 2, T3 SWB β = −.13 (p = .049) versus β = −.22 reported earlier for T3 Materialism; and in Study 3, T2 SWB β = −.24 (p < .01) versus β = −.30 reported earlier for T2 Materialism. These findings suggest that not only do changes in materialism predict changes in well-being, but that changes in well-being predict changes in materialism, although this latter effect may be somewhat weaker than the former.

Although we have no quarrel with the idea that changes in well-being might sometimes lead to changes in materialism, we remained interested in the possibility that changes in materialism might lead to changes in well-being. To test this idea, we utilized an experimental design in Study 4, reasoning that if changes in materialism can sometimes cause changes in well-being, then well-being improvements should be notable if people received an intervention designed to decrease their materialism. We therefore conducted a randomized trial using an adaptation of an established financial education program that is designed to help families orient their adolescent children away from “spending” and towards “sharing” and “saving” (www.sharesavespend.com).

There were three reasons this particular program had appeal for our purposes. First, it focuses on adolescents, who often place strong emphasis on materialistic goals, but who may not have yet organized their lives around such aims to such an extent that they are resistant to intervention. Second, the program requires the involvement of the adolescents’ parents, who are important influences on the materialism of their children (Kasser et al. 1995) and who can moderate the influence of consumer culture on their children (Buijzen and Valkenburg 2005). Third, the program has an established curriculum with existing materials, videos, hand-outs, and homework assignments that could be adapted for our purposes.

After recruiting a group of adolescents and their parents, we administered baseline assessments of materialism and well-being. We used three different types of measures to assess materialism so as to obtain the most broad-band and reliable assessment possible. We also assessed three different indices of well-being (life satisfaction, anxiety, and self-esteem), each of which has been associated in past cross-sectional research with adolescent levels of materialism (Chaplin and John 2007; Kasser 2005; Schor 2004). We then randomly assigned half of the participants to participate in a three-session intervention designed to decrease their focus on “spending” and increase their focus on “sharing” and “saving.” Twice over the next year, we re-assessed adolescents’ materialism and well-being.

We had two basic hypotheses. First, we predicted that participants assigned to the intervention group would evidence larger decreases in materialism over time than would those in the control group. Second, and most importantly, we predicted that the intervention would most benefit the well-being of those for whom it was primarily designed, that is, for those high in materialism at the outset of the study. Said differently, we predicted that those adolescents who began the study with relatively high levels of materialism and who received the intervention would show larger increases in well-being over time than would those adolescents who began the study with relatively high levels of materialism but who did not receive the intervention. We did not expect the intervention to have notable effects on the well-being of adolescents who began the study with relatively low materialism, as their well-being would presumably already be relatively high and thus quite difficult to increase further with an intervention of this sort.

Method

Participants

Individuals living near a major mid-western US city were informed about the study by pastors in one of five suburban churches, by referral to the ShareSaveSpend (SSS) website after the study was mentioned on a local television news broadcast, or by referral to the SSS website after receiving an informational e-mail sent to individuals on the SSS mailing list. Potential participants were told: that the study concerned family financial decisions and communication with adolescents about money; that both an adolescent and a caregiver would need to consent to participate and would complete three survey packets over the course of the coming year; and that half of the participant-pairs would be randomly assigned to attend a three-session workshop, and to complete homework assignments between sessions, whereas the other half would receive no intervention.

In all, 98 families expressed interest in the study and were mailed an initial Time 1 (T1) packet; of these, 56 were recruited via churches and 42 via the TV broadcast or the e-mail. 92 of these families returned their T1 survey packet by the specified deadline. Of these 92 families, 21 were dropped from analyses for various reasons, including a refusal to be randomized (2), participation of an adolescent with a non-parent (3), attendance at only one of the three sessions (3), substantial missing data at the second and/or third wave of data collection (11), or some combination of these reasons (2).

The remaining 71 adolescents ranged in age from 10 to 17 (M = 12.43, SD = 1.97), were predominantly Caucasian (with 1 each of African/American, Asian, and other), and were almost evenly split between males (35) and females (36). To assess their perception of their families’ socio-economic status, at T1 the adolescents marked on a seven-step ladder how much money their family had in comparison to others; on average the adolescents marked their families as being slightly above middle class (M = 4.59; SD = 0.84).

The parents in the study were predominantly mothers (83 %) and ranged in age from 38 to 57 (M = 45.58, SD = 4.32). At T1, adults also completed the same seven-step ladder measure of income as did the adolescents, yielding a very similar result (M = 4.58, SD = 1.14). More objectively, adults also reported their annual family income, on a 5-point scale from “less than $20 K” to “greater than $100 K.” By this assessment, the sample was solidly upper middle class, with 36.6 % reporting annual incomes between “$70,000 and $100,000” and 50.7 % reporting annual incomes “over $100,000.” These two parental reports were significantly correlated with each other (r = .51, p < .01) and with the adolescents’ report on the ladder measure (rs = .56 and .36, respectively, both ps < .01). Thus, to obtain an overall family socio-economic status variable for use as a control variable in later analyses (see below), we z-scored and averaged these three ratings.

Procedures

After expressing interest in the project, participants were mailed consent forms, T1 survey packets for the adolescent and for the adult, corresponding envelopes in which to place each packet (so as to keep responses confidential from each other), and a larger, self-addressed stamped envelope in which to place both packets for return to our laboratory. The adolescent surveys contained the measures of materialism and psychological well-being relevant to the study (described below), as well as a variety of other instruments not relevant to this study. Adult-adolescent pairs received an honorarium of $10 for completing the T1 survey packet.

Next, participant pairs were assigned to the intervention or control group. Because some of the churches through which recruitment occurred had many more participant pairs than did others, we wanted to ensure that each church had at least some families assigned to the intervention group and some to the control group. Accordingly, we used a form of block random assignment, randomly assigning individuals who had signed up from each of the five churches and from the SSS website to either the intervention or control group. Participants assigned to the control group (n = 35) only received occasional e-mails updating them on the progress of the study, but no intervention. In contrast, participants assigned to the intervention group (n = 36) were invited to three 3-h group sessions, held approximately 4 weeks apart at one of the five churches.

The intervention followed the major themes and exercises of the SSS Financial Sanity curriculum, but also allowed for substantial flexibility in order to facilitate discussion among participants. All sessions were conducted by the founder of SSS (Nathan Dungan), with the aid of a research assistant.

Session 1 began with an overview of the study and distribution of materials to be used during and after the intervention, including: participant guides for both the adult and adolescent; a bank for the adolescent that had separate sections for sharing, saving and spending; and a set of “discussion cards” designed to facilitate conversations about financial issues while participants were at home. The presentations, exercises, and discussion in Session 1 focused on: helping participants feel comfortable talking about money in a large group; the distinction between “needs” and “wants” and the role of advertising and consumer culture in these motives; the definition of “healthy money habits”; the ways in which people’s orientations towards sharing, saving, and spending influence their financial actions and decisions; and the importance of developing a values-based system for financial actions. Participants were given two homework assignments: Track their spending behavior and reflect on their financial habits.

Session 2 commenced with a discussion of the homework assignments and then segued into a set of presentations and discussions about how consumer culture and advertising influence financial actions. The presenter emphasized that without a values-based financial system for making decisions, consumer culture would push individuals towards spending. The presenter also discussed the importance of inculcating sharing and saving habits to counteract the tendency to spend, as well as for their own inherent value. Participants were given four homework assignments: (a) to keep a diary of the advertising messages they encounter; (b) to reflect on the extent to which their spending decisions are influenced by their emotions or values; (c) to reflect on previous sharing and saving activities; and d) to interview people who model good sharing and good saving behaviors.

Session 3 began with a discussion of the homework assignments, and then turned to the primary goal of creating a concrete, values-based plan for future financial behavior. Previous themes regarding advertising, tracking one’s spending behavior, and integrating sharing and saving into one’s financial plan were discussed. Further, in response to parental requests, substantial time was spent discussing optimal allowance systems for the adolescents. Finally, the instructor reminded the participants about ways to keep money conversations alive in their homes and the usefulness of referring back to the SSS materials in the months to come.

Six weeks after the completion of the intervention (i.e., approximately 4 months after completing the T1 survey packets), participants in both the experimental and the control groups were mailed the second (T2) survey packet. The adolescent packet contained the same materialism and well-being measures as at T1, in addition to a variety of other surveys not relevant to the current hypotheses. Adult-adolescent pairs received a $20 honorarium for completing the T2 survey packet. Finally, 8 months later (i.e., approximately 12 months after the completion of the T1 packet and 10 months after the completion of the intervention), participants were mailed the T3 packets, which again contained the same materialism and well-being measures as before, in addition to other surveys not relevant to the current hypotheses. Adult-adolescent pairs received a $10 honorarium for completing this set of measures.

Measures

Materialism

Materialism was assessed at three points in time by combining three different measures. First, we assessed the relative importance of financial success aspirations on a modified, 36-item version of the Aspiration Index (Kasser and Ryan 1993, 1996; Grouzet et al. 2005). Wording was adapted to be more understandable for adolescents, and 12 different domains of goals were assessed with 3 items each on a “1 = not at all important” to “9 = extremely important” scale. Three items assessed financial success aspirations (e.g., “I will have many expensive possessions”; “I will have enough money to buy everything I want”). As in Studies 1 and 2, a relative importance of financial success aspirations score was created by subtracting each participant’s grand mean of the importance of all items (regardless of content) from the average of these three financial success items. The second assessment of materialism entailed averaging ratings of four Likert-type items validated by Kasser (2005) as assessing materialism (e.g., “When I grow up, I want to have a really nice house filled with all kinds of cool stuff”; “It is important to make a lot of money when I grow up”). Adolescents responded to these items on a “1 = Strongly Disagree” to “5 = Strongly Agree” scale. Third, adolescents were presented with a scenario (based on Kasser 2005) in which they reported how they would divide a $100 windfall gift into four categories; the amount they placed in “Buy stuff I want” was used to assess materialism.

These three measures of materialism (i.e., the relative importance of financial success aspirations, average responses to the four materialism survey items, and the amount allocated to purchasing “stuff”) were each z-scored within the sample of 71 adolescents at T1, T2, and T3, and then averaged to create a summary materialism score at each time point. Support for this computational procedure was provided by both inter-correlations among the three variables (rs between .30 and .41 at T1, ps < .01; rs between .18 and .47 at T2, ps < .13; rs between .36 and .52 at T3, ps < .001) and factor analyses at each time point that yielded single factor solutions with each of the three indicators of materialism loading above .50 (Mean loadings = .75, .73, and .78 at T1, T2, and T3, respectively). Higher scores indicate higher materialism. Table 4 reports mean scores at Time 1 for these three materialism measures for the entire sample used in analyses, and for sub-groups split by intervention versus control group and high versus low T1 Materialism score.

Psychological well-being

Three indicators of well-being in “the last month” were assessed at each time point. First was the 5-item Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al. 1985), rated on a “1 = Strongly Disagree” to “7 = Strongly Agree” scale (e.g., “In most ways my life is close to my ideal”; Cronbach’s αs = .81, .80, .80 at T1, T2, and T3 respectively). Second was the Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (Reynolds and Richmond 1978), in which participants answered “yes” or “no” to whether they have experienced 16 symptoms of anxiety (e.g., “I worry a lot of the time”; Cronbach’s αs = .79, .94, .75 at T1, T2, and T3 respectively). Finally, the 10 items of the widely-used Rosenberg (1965) self-esteem scale were assessed on a “1 = Strongly Disagree” to “5 = Strongly Agree” scale (e.g., “On the whole, I am satisfied with myself”; Cronbach’s αs = .82, .85, .80 at T1, T2, and T3, respectively). High scores on each of these scales represent higher levels of satisfaction, anxiety, and self-esteem, respectively. Table 4 reports mean scores at Time 1 for these three well-being measures for the entire sample used in analyses, and for sub-groups split by intervention versus control group and high versus low T1 Materialism score.

Results

Attrition analyses

T tests were conducted to examine differences between the 71 adolescents used in the analyses and the 21 dropped from analyses for one of the reasons noted above. No differences were noted on any of the three measures of adolescent materialism or the three measures of adolescent well-being (all ps > .36), nor were there differences on age (p = .77) or gender (tested via χ2, p = .37). Wealthier adolescents were, however, more likely than poorer adolescents to have sufficient data and attendance at the sessions to warrant their inclusion in analyses; this was revealed via the adolescents’ report of family income using the ladder measure (p = .09), and the adults’ report of family income using both the ladder measure and the stepped 5-point family income scale (ps < .01). Thus, as in Study 1, while there was no differential attrition on the basis of key study variables, attrition was higher for poorer individuals.

Inter-correlations of primary study variables

Correlations between summary materialism scores across the three time periods revealed substantial stability in the summary materialism score (T1/T2 r = .77, T2/T3 r = .77, T1/T3 r = .66, all ps < .001). Similar stability was noted for life satisfaction (T1/T2 r = .47, T2/T3 r = .65, T1/T3 r = .34, all ps < .01) and for self-esteem (T1/T2 r = .73, T2/T3 r = .46, T1/T3 r = .47, all ps < .01); stability of anxiety was somewhat lower (T1/T2 r = .23, p = .06, T2/T3 r = .30, p < .05, T1/T3 r = .56, p < .01.

At each time period, we examined associations between materialism and each well-being measure (rs > |.23| are significant at p < .05). Materialism was associated with lower levels of life satisfaction (rs = −.19, −.40, and −.30 at T1, T2, and T3, respectively) and of self-esteem (rs = −.24, −.21, and −.25 at T1, T2, and T3, respectively). Correlations with anxiety were weaker and less consistent, though generally positive (rs = .21, .02, and .18 at T1, T2, and T3, respectively).

We did not calculate cross-correlations, given that the intervention occurred after T1.

Effect of the intervention on materialism scores

To examine whether the SSS intervention was successful in reducing materialism, we conducted latent growth curve analysis, the preferred means of testing change when the same measures are assessed at least three times. This analysis involved two outcome variables: intercept (i.e., T1 Materialism score) and slope (i.e., change in materialism from T1 to T2 to T3), both of which can vary across individuals (and hence are random coefficients). The predictor variable was condition, which was dummy coded as Intervention = 1 and Control = 0. Results are reported in Table 5. The model provided a good fit to the data (χ2 = 3.66, df = 2, ns; CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.10, SRMR = 0.03).Footnote 7

Of initial interest is the non-significant relation (0.147, p = .41) between condition and the intercept (which represents materialism scores at Time 1). This result means that adolescents in the intervention group had equivalent T1 Materialism scores to those in the control group, i.e., that random assignment was successful regarding materialism.

Of primary interest, a significant negative relationship between condition and slope was detected (−0.103, p < .05). This reflects the finding that adolescents in the intervention condition tended to decrease in materialism relative to adolescents in the control group. Supplementary analyses showed that those in the control group increased in materialism from T1 to T3 (the simple slope = 0.05) whereas those in the intervention group decreased in materialism from T1 to T3 (the simple slope = −0.05). Thus, the intervention was effective in reducing materialism, and perhaps protected against the increase in materialism that was notable in the control group (an increase that has been detected in previous cross-sectional studies of adolescents (Chaplin and John 2007).Footnote 8

Additionally, there was a non-significant association between the predictor variable of intercept and the outcome variable of slope (0.050, p = .15). This finding means that the rate of change in materialism from T1 to T3 was independent of adolescents’ T1 Materialism scores.

Finally, we re-ran the model after controlling for demographic variables. Analyses which controlled for the family’s socio-economic status and the child’s gender left the results essentially unchanged, but controlling for age did reduce the size of the effect of the intervention to a non-significant trend (p = .12).

Hypothesis testing

Having established that the intervention was effective in reducing adolescents’ materialism scores, we next tested our primary hypothesis. Recall our prediction that personal well-being would increase more for adolescents who began the study with high levels of materialism and who received the intervention than it would for adolescents who began the study with high levels of materialism but who did not receive the intervention. We did not expect the intervention to affect the well-being of adolescents who began the study with low levels of materialism, given their presumably high initial well-being. Statistically, we therefore predicted an interaction between condition (intervention vs. control) and adolescents’ T1 Materialism scores in explaining changes in well-being over time. To test this hypothesis, we conducted three separate latent growth curve analyses, one for each of the well-being outcomes (i.e., life satisfaction, self-esteem, and anxiety). In each analysis, the dependent variables were the relevant well-being scores at each of the three times of assessment. The predictors were condition (i.e., intervention vs. control), the adolescents’ T1 Materialism scores, and the interaction between these two predictor variables.

No significant findings were obtained for either life satisfaction (ps = .58 and .26 for main effects of Intervention vs. Control and for T1 Materialism, respectively; p = .22 for the interaction of condition by materialism) or anxiety (ps = .75 and .64 for main effects of Intervention vs. Control and for T1 Materialism, respectively; p = .95 for the interaction of condition by materialism). Results for self-esteem were, however, supportive of our hypothesis, and the model for this outcome variable provided a good fit to the data (χ2 = 4.72, df = 4, ns; CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.05, SRMR = 0.05). The results of the latent curve model for self-esteem are presented in Table 6.

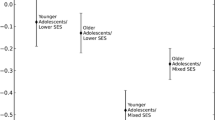

There, it can be seen that while condition was non-significant (0.041, p = .31), both T1 Materialism (−0.104, p < .01) and the interaction between T1 Materialism and condition (0.179, p = .001) had significant effects on the slope factor (which represents the linear change in self-esteem from T1 to T3). In order to understand this interaction, we calculated the simple intercepts and slopes, and the regions of significance and confidence bands for the slopes, following the methods described by Curran et al. (2004) and using their online calculator (Preacher et al. 2006; see also Bauer and Curran 2005; Curran et al. 2006). As Curran et al. (2004, 2006) point out, a two-way interaction of exogenous predictors of the slope factor should be interpreted as a three-way interaction, with time as the third factor. Figure 1 depicts this three-way interaction, showing how self-esteem changed over time separately for participants high or low (i.e., 1 SD above and below the mean) in T1 Materialism who were in either the intervention or the control group. As suggested by Fig. 1, the simple slope representing change in self-esteem from T1 to T3 was not significant for adolescents low in materialism at Time 1, regardless of whether they were in the intervention (slope = −0.04, z = −0.91, ns) or control group (slope = 0.06, z = 1.59, ns). Thus, as expected, the intervention did not affect the well-being of adolescents who began the study low in materialism. However, for adolescents who began the study high in materialism, the slope representing change in self-esteem from T1 to T3 was significantly negative in the control group (slope = −0.10, z = −2.25, p < .05) but was significantly positive in the intervention group (slope = 0.08, z = 2.05, p < .05). Thus, as expected, adolescents who began the study high in materialism and who received the intervention experienced increases in their self-esteem, whereas those who began the study high in materialism and did not receive the intervention experienced decreases in their self-esteem over time (consistent with the past findings of Chaplin and John 2007).

Because the trajectories of participants’ changes in self-esteem over time depended on both their T1 levels of materialism and on whether they were in the intervention or control group, we followed the recommendations of Curran et al. (2004) in order to clarify the regions of significance for values of T1 Materialism in which there was a significant slope effect (i.e., significant changes in self-esteem over time). In these analyses, the upper and lower bounds define those values of materialism for which the slope is not significant (i.e., no change in self-esteem); values of T1 Materialism outside of those bounds represent values of T1 Materialism for which the slope is significant (i.e., some change in self-esteem). For participants in the control group, these analyses estimated that significant positive change in self-esteem would be found for those lower than 1.35 SDs from the mean of T1 Materialism (i.e., the bottom 16 % of the distribution) and significant negative change in self-esteem would be found for those higher than 0.65 SDs above the mean of T1 Materialism (i.e., the top 32 % of the distribution). For participants in the intervention group, these analyses estimated that significant negative change would be found only for those participants more than 682 SDs below the mean of T1 Materialism (i.e., a vanishingly small proportion of participants), whereas significant positive changes in self-esteem would be found for those 0.84 SDs above the mean in T1 Materialism (i.e., the top 28 %). In sum then, these analyses showed that changes in self-esteem were most notable for those participants moderately high in T1 Materialism (approximately the top 30 %). Such individuals showed an increase in self-esteem if they received the intervention but a decrease in self-esteem in the absence of the intervention. In contrast, the self-esteem of participants low in T1 Materialism was very unlikely to change in the intervention group, although those who were very low in T1 Materialism did show some slight positive change in self-esteem if they were in the control group.

Finally, we re-ran all of the analyses reported above after controlling for family socio-economic status and the child’s age and gender; results were essentially unchanged.

Brief discussion

Study 4 made at least two important and novel contributions to this series of studies in particular, and to the literature in general. First, the results showed that it is possible to intervene in adolescents’ lives so as to decrease the priority they place on materialistic goals. Compared to those in the control group, adolescents assigned to the three, 3-h intervention sessions oriented away from materialistic aims in life, a tendency still evident months after the intervention ended. Second, the results showed increases in the self-esteem of adolescents who began the study with strong materialistic aims in life and who received the intervention; in contrast, more materialistic adolescents who did not receive the intervention decreased in their self-esteem over time. Not only do these findings have important practical worth, they also point to the possibility that decreasing materialistic goals can lead to increases in self-esteem.

It is worth noting that self-esteem was the only well-being variable significantly affected by the intervention; results for life satisfaction trended in the predicted direction, and results for anxiety were essentially nil. Perhaps self-esteem is more malleable than these other well-being outcomes among adolescents. Along these lines, Chaplin and John (2007) found that temporarily boosting adolescents’ self-esteem decreased their expression of materialistic concerns when assessed moments later. That short-term laboratory study, combined with our longer-term field study, suggests that self-esteem may be especially closely connected with materialistic strivings, at least among adolescents.

Of course, there are numerous weaknesses to this intervention study; three inter-related problems deserve special mention. First, given the broad band of topics discussed in the sessions, other (unmeasured) variables than materialism may also have been affected, and these may have influenced the observed changes in self-esteem. Second, demand characteristics may have played a role in the results, as the intervention clearly critiqued materialistic values (although participants were not informed about the hypotheses) and the participants had volunteered to participate in a study on “sharing, spending and saving”; as such, response biases may have affected the observed results. Finally, and most crucially, participants in the control group received very little attention or contact from the experimenters or from each other, leaving open the possibility that the mere fact of participating in the intervention affected participants’ materialism and self-esteem. Future research is needed that utilizes a placebo treatment group and that includes participants who may be less inclined to respond positively to the messages of the intervention.

General discussion

Previous research has established that people report lower well-being to the extent they focus on materialistic aims for money, wealth, and possessions (see Kasser 2002; Dittmar 2008). Most of the data supporting this claim has been based, however, on cross-sectional, correlational studies, leaving two important questions unanswered. First, are changes in materialistic goals associated with changes in well-being? Second, do experimental interventions that change materialistic goals lead to changes in well-being? The present manuscript reported four studies relevant to these questions.