Abstract

Based on the Dualistic Model of Passion (Vallerand et al. in J Pers Soc Psychol 85:756–767, 2003), a bidimensional perspective on romantic passion, that distinguishes between harmonious and obsessive passions, is proposed. The present research aimed at examining how these two types of romantic passion relate to indices of relationship quality, how one’s own passions are associated with one’s partner’s passions and relationship quality, and how the two types of passion relate to relationship stability over time. Study 1 revealed that harmonious passion was more strongly associated with high relationship quality than obsessive passion. Using a dyadic design, Study 2 revealed that the findings of Study 1 applied to both genders. In addition, one’s own passion predicted partner’s relationship quality, partners were not always matched in terms of the predominant type of passion, and passion matching did not predict relationship quality. Finally, Study 3 revealed that types of passion predicted relationship status over a 3-month period.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It is difficult to overcome our passions, and impossible to satisfy them. Marguerite de La Sablière (1636–1693).

The message conveyed above is that although (or perhaps because) passion is beyond individual control, it may not lead to highly positive experiences. However, is this in fact true? Is passion really beyond our control or can we control our passion toward a loved one? What are the consequences of being passionate toward someone? Can the outcomes be fully positive? Recently, using a new conceptualization of passion for activities (Vallerand 2008, 2010; Vallerand et al. 2003), research has shown that passion for activities such as work and leisure can influence the quality of relationships experienced both within the purview of the passionate activity as well as outside of it (Lafrenière et al. 2008; Philippe et al. 2010; Séguin-Lévesque et al. 2003). Using this new conceptualization of passion, the purpose of the present research was to examine how romantic passion relates to relationship quality and associated outcomes.

The dualistic model of passion

The Dualistic Model of Passion (DMP; Vallerand et al. 2003; Vallerand 2008, 2010) proposes a motivational conceptualization of passion toward activities, defining passion as “a strong inclination toward an object or activity that we like (or even love), find important and in which we invest time and energy” (Vallerand et al. 2003, p. 757). Two types of passion are described. Harmonious passion is a motivational tendency whereby people deliberately choose to engage in the activity that they love. Because they do not feel obligated to engage in the activity, they do it autonomously. As its name implies, this type of passion is in harmony with other life domains and does not encompass the entire self. For instance, a librarian with a predominantly harmonious passion for books might like and value books and researching new editions but can put aside this time-consuming task at home to attend to other activities such as spending quality time with her children, exercising, etc. Conversely, obsessive passion is an internal pressure that pushes individuals to engage in an activity that they like, value, and invest time and energy in. Individuals cannot help but to engage in the beloved activity because the passion controls them. For example, an athlete with a predominantly obsessive passion for hockey might love and value this activity so much that he comes to neglect other important life domains such as his family and his work, to the point where he experiences conflicting thoughts. Obsessive passion for an activity should not be confused with the concept of addiction. Both obsessive passion and addiction are characterized by an inability to resist the urge to engage in some form of behavior. Nevertheless, an important distinction between these two constructs is that individuals who have an obsessive passion for an activity highly value and enjoy the activity they engage in whereas for addiction, high involvement is coupled with low enjoyment (see Philippe et al. 2009). It has further been posited (e.g., Lafrenière et al. 2009) that obsessive passion may represent a precursor to addiction.

According to the DMP, the way in which the activity has been internalized into the identity will determine the type of passion that is developed toward the activity. Research on Self-Determination Theory (Deci and Ryan 2002) has shown that the reasons for doing non-interesting activities can be internalized in two ways: 1) a controlled manner whereby they are part of the self, although because they have not been choicefully internalized and are therefore not fully integrated, they will consequently generate conflict with other components of the self as well as an internal pressure to engage in the activity; or 2) an autonomous manner whereby the person choicefully accepts them as part of the self. This process produces a motivational force that leads the person to freely engage in the passionate activity, without conflicts with other activities or domains. According to the DMP, interesting activities can also be internalized in the identity and the manner in which this is done determines the type of passion that is developed. Accordingly, an autonomous internalization (i.e., activity engagement based on reasons such as choice, volition, interest) leads to harmonious passion, whereas a controlled internalization (i.e., activity engagement based on reasons like obligation, extrinsic incentives, guilt, ego-involvement) is conducive to obsessive passion. Hence, valuing an activity and internalizing it in one’s identity will be important for the development of a passion toward this activity. Furthermore, the way this activity is internalized in the self will predict which type of passion will be predominantly developed, although both types of passion coexist within the self. Hence, depending on individual and environmental factors, one or the other can become more important (see Vallerand 2010).

Empirical support has been provided for several aspects of the passion conceptualization (see Vallerand 2008, 2010, for reviews). First, results from exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses with the Passion Scale (e.g., Vallerand et al. 2003, Study 1; Vallerand et al. 2006, Study 1) support the existence of two constructs corresponding to harmonious and obsessive passion. Second, partial correlations (controlling for the correlation between the two types of passion) reveal that both harmonious and obsessive passion are positively associated with measures of activity valuation and measures of the activity being perceived as a passion, thereby proving support for the definition of passion. Empirical evidence has also shown that the two types of passion differently predict various outcomes. As pertains to psychological and physical well-being, harmonious passion has been shown to be positively related to positive emotions and psychological adjustment as well as negatively related to negative emotions, anxiety, and physical symptoms (e.g., Lafrenière et al. 2009; Philippe et al. 2010; Vallerand et al. 2003). Conversely, obsessive passion is typically positively associated with negative outcomes (e.g., negative emotions, anxiety, etc.) and either negatively related or unrelated to indices of psychological and physical well-being. Also, only obsessive passion is positively related to conflict with other aspects of one’s life (Séguin-Lévesque et al. 2003; Vallerand et al. 2003, Study 1), to rumination and negative affect when the person is prevented from engaging in the passionate activity (Vallerand et al. 2003, Study 1), and to rigid persistence in ill-advised activities (Vallerand et al. 2003, Studies 3 and 4) that can eventually lead to chronic injuries in dancers (Rip et al. 2006), and pathological gambling (e.g., Philippe and Vallerand 2007).

The DMP therefore offers a new, motivational framework that distinguishes between healthy and maladaptive forms of passionate involvement. This distinction is important for understanding individual experiences during activity engagement and we propose that such a distinction is also important to consider as it promises to provide a better understanding of romantic relationships.

On passion and relationships

Past research has shown that passion can affect the quality of relationships in at least two fashions. First, one’s passion for a given activity influences the relationships that one develops while engaged in this activity. For instance, Lafrenière et al. (2008) found that athletes’ harmonious passion toward their sport was positively related to various indices of relationship satisfaction with their coach (Lafrenière et al. 2008, Study 1). Conversely, athletes’ obsessive passion toward their sport was either unrelated or negatively related to these indices of relationship satisfaction. Similarly, passion for a given activity (e.g., work) can affect the quality of relationships that one develops in such settings (e.g., at work). For example, Philippe et al. (2010, Studies 3 and 4) found that having a harmonious passion for an activity leads to the development of new positive interpersonal relationships within the context of the passionate activity, while obsessive passion is unrelated to the quality of interpersonal relationships.

A second way through which passion for an activity can affect the quality of one’s relationships is through its influence in other spheres of human functioning, outside the purview of the passionate activity. For instance, Séguin-Lévesque et al. (2003) have shown that controlling for the number of hours that people engaged in the Internet, obsessive passion for the Internet was positively related to conflict with one’s spouse, while harmonious passion was unrelated to it. In the same vein, a study conducted with English soccer fans (Vallerand et al. 2008, Study 3) showed that obsessive passion for being a soccer fan predicted conflict between one’s passion for soccer and one’s romantic relationship which, in turn, predicted lower quality of the romantic relationship. Conversely, harmonious passion was unrelated to conflict with one’s spouse.

On romantic passion

In line with Vallerand et al. (2003; Vallerand 2008, 2010), we propose that the dualistic conceptualization of passion also applies to romantic involvement. Based on the DMP, romantic passion is defined as a strong inclination toward a romantic partner that one loves, in a relationship that is deemed important, and into which significant time and energy is invested. From our perspective, feelings of love, while distinguishable from passion (Fletcher et al. 2000), nevertheless represent a component of passion. In line with the original Vallerand et al. (2003) definition of passion and that dealing with romantic passion presented above, to experience passion toward a romantic partner, feelings of love are necessary but insufficient. For passion to be present, one also needs to invest time and energy in the relationship and to perceive the latter as important.

Of major importance is the fact that two types of romantic passion are proposed. Obsessive passion refers to an internal pressure that drives people to pursue a romantic relationship with their partner. With obsessive passion, people feel that the passion controls them and that it must run its course. Because obsessive passion takes over most of the self and comes to control the individual, this type of passion can create conflicts with other life spheres. Obsessive passion is more closely related to existing views of romantic passion (e.g., passionate love). Conversely, harmonious passion refers to a motivational tendency whereby people willingly choose to engage in a romantic relationship with the partner. Because people do not feel obligated to pursue this type of passionate relationship, they do so autonomously. Their romantic passion is in harmony with other life domains.

Some authors (e.g., Hatfield and Rapson 1993a, b, 2000) proposed one type of passion (i.e., passionate love) and suggested that positive outcomes derived from it when love was reciprocated whereas negative outcomes were experienced when the love was unreciprocated or when the relationship dissolved. This hypothesis ignores an important aspect of individual experience: the fact that negative outcomes can also take place in a reciprocal relationship. Here, we propose that passion can lead to both positive and negative outcomes even in ongoing and reciprocal relationships, depending on the type (i.e., harmonious vs obsessive) of passion that is developed. Specifically, in line with past passion research (see Vallerand 2010 for a review), positive outcomes should be mainly associated with harmonious romantic passion, whereas negative outcomes should be mainly associated with obsessive romantic passion. Kim and Hatfield’s (2004) findings that show that subjective well-being was unrelated to passionate love might therefore be explained by the moderating effect of type of passion. Third, we believe that passion does not necessarily erode with time. Defined as an emotion, passionate love has been recognized by many theorists as being short-lived (Reeve 1997). Research by Hatfield et al. (2008) documented an erosion of passionate love over time for married couples. From our perspective, passion is not a function of novelty but rather depends on how the loved one has been internalized in the partner’s identity. Thus, harmonious and obsessive passion can remain high even years into a relationship. Fourth, because harmonious passion is typically associated with personal and relational benefits and entails an autonomous decision to partake in and maintain one’s relationship, we believe that this type of passion sets the stage for a fulfilling and lasting relationship. Conversely, we believe that the controlled nature of obsessive passion and its maladaptive by-products will eventually erode the relationship and might even lead to its dissolution.

Previous research (Ratelle 2002) on harmonious and obsessive romantic passion has brought support for the bidimensional conceptualization of romantic passion. The Romantic Passion Scale (RPS) was developed and its psychometric qualities were examined (see Table 1 for the items and the psychometric qualities of the RPS). Both harmonious and obsessive passion subscales were found to be reliable. Results from factor analysis yielded two factors corresponding to harmonious and obsessive passion. In addition, the temporal stability of both types of romantic passion was supported. Thus, the RPS represents a psychometrically sound instrument that allows a valid and reliable measurement of harmonious and obsessive romantic passions. Support was also provided for the validity of the Dualistic Model of Passion as applied to romantic relationships (Ratelle 2002). Specifically, the two types of passion were found to be strongly and positively related to measures of passion (in one’s romantic relationship, Sternberg 1997) and passionate love (Hatfield and Sprecher 1986) but only harmonious passion was significantly related to physical passion within one’s relationship (see Aron and Westbay 1996). Companionate love (Hatfield and Walster 1978; Sternberg 1997), while being positively associated with both types of passion, shared more similarities with harmonious than obsessive passion. Results also showed that only harmonious passion was positively and significantly related to constructs such as intimacy (Sternberg 1997), optimism toward the future of the relationship (Murray and Holmes 1997), and dyadic adjustment (Baillargeon et al. 1986; Spanier 1976). All these correlations were moderately high suggesting that harmonious and obsessive passion, although related to these various relationship experiences, nevertheless represent conceptually and empirically distinct constructs.

The present research

The purpose of the present series of studies was to further examine relational benefits associated with harmonious and obsessive romantic passion in order to further establish the pertinence of distinguishing these two types of passion. Specifically, Study 1 aimed at examining how the two types of passion related to evaluative components of relationship quality (e.g., satisfaction, commitment, trust, etc.). Study 2 further explored the role of passion in relationship quality from a dyadic perspective, where the two types of passion of both partners were used to predict components of relationship quality. In addition, we also tested whether the matching of passion type within a couple (i.e., where one or both partners had a harmonious or obsessive passion) was adaptive. Finally, using a prospective design, Study 3 examined whether the two types of passion could predict which individuals would still be involved in the same romantic relationship 3 months later.

Study 1

In various spheres of activities, the two types of passion were found to be associated with different individual and relational experiences where more adaptive functioning is observed when passion is harmonious rather than obsessive (see Vallerand 2010 for a review). In the present study our specific goal was to test whether components of relationship evaluation (i.e., satisfaction, commitment, intimacy, trust, physical passion, and love; Fletcher et al. 2000) were differently predicted by the two types of passion. In line with previous research on passion toward an activity that supported the individual as well as relational advantages associated with harmonious passion, we expected that harmonious romantic passion would more strongly predict the evaluative components than obsessive passion.

Method

Participants and procedure

Undergraduate students (n = 176; 136 women, 37 men; 3 not specified) in an ongoing romantic relationship were recruited in class and given a questionnaire to assess harmonious and obsessive passion and dimensions of relationship quality. Mean age was 25 years (range 17–54 years) and the majority of participants were Francophone (97 %). Average relationship length was 3 years and 8 months (SD = 4 years and 2 months).

Measures

Harmonious and obsessive passion

Harmonious and obsessive passion were measured with the RPS (α = .86 and .89 for harmonious and obsessive passion respectively).

Relationship quality

The Perceived Relationship Quality Components Inventory (PRQCI; Fletcher et al. 2000) was used to measure the components of relationship quality: satisfaction, commitment, intimacy, trust, sexual passion,Footnote 1 and love (3 items each). Items such as “How satisfied are you with your relationship?” (satisfaction; α = .96), “How committed are you to your relationship?” (commitment; α = .90), “How intimate is your relationship?” (intimacy; α = .89), “How much do you trust your partner?” (trust; α = .93), “How passionate is your relationship?” (sexual passion; α = .90), and “How much do you love your partner?” (love; α = .87) were scored on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (extremely).

We also collected information on the relationship itself (i.e., relationship length, whether the partners lived together, etc.) as well as sociodemographic information (i.e., age, gender, etc.).

Results and discussion

Preliminary analyses

The data was screened and showed no violation of the basic statistical assumptions (see Tabachnick and Fidell 2007). We performed a MANOVA which revealed no gender differences on our measures (Wilks λ [14,125] = .88; p = .09. Correlational analyses revealed a non-significant correlation (r = .09, p = .22) between obsessive and harmonious passion, suggesting that the two types of passion did not overlap in this sample. Relationship length was negatively correled with harmonious and obsessive passions (r = −.16 and −.21, respectively; ps < .05) but unrelated to components of relationship quality. Also, gender (coded such that 1 represented being a man) was significantly correlated with harmonious passion, satisfaction, and commitment (rs = −.23, −.20, and −.24, respectively; ps ≤ .01). In light of these findings, gender was used as a control variable in subsequent analyses.

Relational correlates of harmonious and obsessive passion

Regression analyses were performed for all dimensions of relationship quality with harmonious and obsessive passions as predictors while controlling for gender. Results presented in Table 2 showed that harmonious passion was a strong a positive predictor of all evaluative components whereas obsessive passion predicted decreasing levels of trust and increasing levels of commitment and love. We also performed statistical tests to compare the contributions of both types of passion and found the contribution of harmonious passion to all components of relationship quality to be statistically higher than that of obsessive passion (see the right portion of Table 2). Together, harmonious and obsessive passions explained from 23 to 63 % of the variance of relationship quality components.

Thus, in line with our hypothesis, the findings obtained in Study 1 suggested that harmonious passion predicted components of relationships quality more strongly and positively than obsessive passion. Obsessive passion was characterized by love and commitment—which is not surprising given that central features of romantic passion include love of the romantic partner and time and energy investment in the relationship—but was not associated with the benefits of having intimacy and being satisfied. Worse, it was associated with distrust for the partner. This paradoxical finding reflects the conflictual nature of obsessive passion. Individuals experiencing obsessive passion appear to be trapped in a rigid persistence pattern (see Vallerand et al. 2003, Studies 3 and 4) whereby they stay in the relationship despite the absence of positive experiences and the occurrence of some negative ones.

Study 2

The results of Study 1 showed that harmonious and obsessive passion were differently associated with indices of relationship quality. However, these results were obtained considering only one partner of the couple. A first objective of Study 2 was to examine the contribution of the participant’s own harmonious and obsessive passion to the partner’s relationship quality. In line with our previous findings, we predicted that the participant’s harmonious passion would be more positively associated with the partner’s relationship quality than obsessive passion. In testing these relations, the partner’s own passion was taken into account. This allowed us to test the additional contribution of one’s passion to the partner’s relationship quality over and beyond the contribution of the partner’s own type of passion.

A second objective was to test whether romantic partners had matching types of passion and how this would relate to relationship quality. Tucker and Aron (1993) found that partners’ levels of passionate love were comparable (labeled the homogamy hypothesis—the mating of similar partners; see Hahn and Blass 1997), whereas Gao (2001) found discrepancies between men’s and women’s reported levels of passion (based on the Theory of Love; TTL, Sternberg 1986). In light of this mitigated evidence and the fact that we used different constructs from those used in past research, no specific hypotheses were formulated. In terms of associated outcomes, there is evidence that discrepancies in passionate love have relational costs (i.e., low physical passion, intimacy, care, commitment, and satisfaction; Davis and Latty-Mann 1987; Morrow et al. 1995). For this reason, we expected mismatched couples to show low levels of relationship quality. Based on the findings of Study 1 and on research on passion toward an activity (see, for example, Vallerand et al. 2003; Vallerand 2010), we hypothesized that high levels of matched obsessive passion in both partners would predict the most negative indices of relationship quality, whereas matched harmonious passion would predict the highest indices of relationship quality.

A final objective was to test gender differences in types of passion. Recruiting heterosexual couples allowed us to test the generalizability of our previous findings to men in two aspects: absolute levels of passion and relations between passion and relationship quality. Studies that investigated gender differences using different measures of passion from ours (i.e., passionate love, Eros, or TTL’s passion) reported contradictory findings (see Fehr and Broughton 2001 for a review). Similarly, the previous research is inconclusive on the moderating effect of gender on the relations between passion and relational outcomes, with some studies showing gender moderation (e.g., Aron and Henkemeyer 1995; Regan 2000b) and others reporting similar correlational patterns for men and women (Davis and Latty-Mann 1987; Hendrick et al. 1988). In light of these inconsistent findings, no specific hypotheses were formulated with respect to gender effects.

Method

Participants and procedure

Participants were 116 heterosexual couples engaged in an ongoing relationship. They were recruited from colleges in the Montreal area. Mean age was 19 years (SD = 3.62) for women and 21 years (SD = 4.44) for men. Average relationship length was 2 years (SD = 3 years). One partner of the couple (n = 201) was recruited in class and given a questionnaire to fill out. At the completion of the questionnaire, participants were asked to indicate the electronic and postal addresses of their partners so that we could send them the same questionnaire. The time lag between the two partners’ completions of the questionnaire was 2 to 3 weeks. Of the 201 partners contacted, 116 completed the questionnaire, yielding a response rate of 58 %.

Measures

Harmonious and obsessive passion

The RPS was used to measure harmonious and obsessive passion (harmonious, α women = .84, α men = .81; obsessive, α women = .89, α men = .88).

Relationship quality

We used the PRQCI described in Study 1 (αs ranged from .75 to .96).

In addition, information about the relationship (e.g., length, whether partners live together, etc.) and demographic information (e.g., age, gender, etc.) were collected.

Results

Preliminary statistics

First, the data was screened and inspection of z distributions revealed the presence of a few univariate outliers on measures of harmonious passion and some components of relationship quality. Tabachnick and Fidell (2007) suggested that the score of outlying cases can be changed to decrease their deviance from the rest of the sample. Since scores higher than 3.29 (and lower than −3.29) are considered outliers, we assigned this threshold value (−3.29/3.29) to all cases below −3.29 or above 3.29. Second, gender differences were examined. A one-way within-subject MANOVA on men’s and women’s scores yielded a significant Wilk’s Λ (value = .005; df = 8. 85; p < .001), indicating that men and women scored differently on several measures.Footnote 2 Paired t-tests revealed that men and women did not differ on measures of passion or on several indicators of relationship quality, except for commitment (M men = 5.87, M women = 6.10; t [115] = 1.97, p = .05, η2 = .03) and intimacy (M men = 6.16, M women = 6.33; t [113] = 1.92, p = .06, η2 = .03), where women scored higher than men, although these differences were of small magnitude.Footnote 3 Finally, correlational analyses were conducted on men’s and women’s scores. Inspection of correlation coefficients revealed that: (1) the correlation between obsessive and harmonious passion was positive for both genders but significantly higher for men (r men = .51, p < .001; r women = .27, p = .004; z = 2.14, p = .03, q = .29); and (2) correlation patterns were almost identical for both genders, except for the relation between harmonious passion and sexual passion, which was stronger for men (r men = .57, p < .001; r women = .25, p = .007; z = 2.91, p = .004; q = .40). Relationship length was unrelated to all measures except for men’s harmonious passion, which was negatively related to the length of the relationship.

Relationship quality as a function of one’s own and partner’s passion

Hierarchical multiple regressions were conducted on the dimensions of relationship quality, using one’s own and partner’s harmonious and obsessive passions as predictors. Data were entered in a dyadic structure, which allowed us to control for interdependence of partners’ data, as suggested by Kenny et al. (2006). We opted not to perform multilevel analyses because our goal was not to explain within-couple (level 2) variance. Using such analyses would only have added unnecessary complexity to the paper.

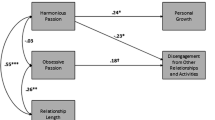

Participants’ own types of passion were entered first, followed by the partner’s (see Table 3). While we replicated the intraindividual effects from Study 1 (see Steps 1), two main conclusions can be drawn with respect to partner effects. First, for both men and women, partner’s harmonious passion predicted one’s own relationship quality even when one’s own passion was controlled for. In fact, women’s satisfaction, intimacy, and sexual passion increased with partner’s harmonious passion (βs = .25, .27, and .34, respectively, ps ≤ .005), whereas women’s sexual passion decreased with partner’s obsessive passion (β = −.22, p = .03). For men, we also found that their satisfaction was facilitated by their partner’s harmonious passion. Second, men’s passion contributed more strongly to women’s relationship quality than women’s passion contributed to men’s relationship quality. For instance, men’s harmonious passion predicted an increase in women’s intimacy and sexual passion (βs = .27 and .34, respectively) that was equivalent to the contribution of women’s own harmonious passion (βs = .28 and .19, respectively, ps ≤ .05; z = −.08 and 1.22, respectively; ps < .05). Moreover, women’s sexual passion decreased with men’s obsessive passion, with men’s obsessive passion showing a stronger contribution (β = −.22) to this dimension than women’s own obsessive passion (β = .10, p = .28). Overall, men’s passion explained an additional 5–11 % variance on these indices of women’s relationship quality. The contribution of women’s passion to indices experienced by males was much less important (see Table 3).

Partners’ matching passion and relationship quality

The positive correlations between men’s and women’s passion suggest some overlap between men’s and women’s harmonious and obsessive passion (rs = .26 and .23 for harmonious and obsessive passions, respectively). To examine the matching of partners’ predominant types of passion, passion scores were standardized and obsessive passion was subtracted from harmonious passion such that a positive value reflected having stronger harmonious than obsessive passion and vice versa (see Mageau et al. 2009). Individuals were categorized into two groups: high harmonious passion versus high obsessive passion. Twenty-three couples matched on harmonious passion and 32 couples matched on obsessive passion, with 29 couples composed of a highly obsessive man and a highly harmonious woman, and 31 couples composed of a highly harmonious man and a highly obsessive woman. A nonsignificant contingency analysis suggested that romantic partners were not necessarily matched in terms of predominant type of passion (χ2 = .06, df = 1, p = .80).

We then examined the relationship quality of the partner as a function of matching status using 2 (highly harmonious women vs. highly obsessive women) × 2 (highly harmonious men vs. highly obsessive men) MANOVAs. For women’s indices of relationship quality, a nonsignificant Wilks (value = .94, df = 6,102; p = .41) was obtained, suggesting that having matching types of passion was not significantly associated with women’s indices of relationship quality. For men, a marginally significant Wilks λ was obtained (value = .89, df = 6,102; p = .07), suggesting that matching status tends to be associated with some indices of men’s relationship, although these findings must be interpreted with caution. Univariate tests for 2 × 2 ANOVAs are presented in Table 4. Results revealed significant interactions on commitment, intimacy, sexual passion, and love. Specifically, men reported the highest levels of commitment, intimacy, and sexual passion when they were predominantly harmonious and their partner was predominantly obsessive. They also reported being least satisfied and least in love when both partners were predominantly obsessive, although the result for satisfaction was marginal (p = .06). Some main effects for men’s passion type were also obtained on satisfaction and intimacy but were qualified by the interaction with women’s passion type. Taken together, these findings suggest that matched type of passion was not important for predicting women’s relationship quality, and that it was marginally important for men’s relationship quality.

Discussion

The present study examined the relations between types of passion and relationship quality at the individual and dyadic level. In testing the contributions of types of passion to relationship quality, we found that while one’s own passion is usually a stronger predictor of the relationship quality, the partner’s type of passion is important to consider as well. Men’s and women’s satisfaction, as well as women’s intimacy and sexual passion, increased significantly with the partner’s harmonious passion. In addition, women’s sexual passion decreased significantly with the partner’s obsessive passion. These findings add to the previous research on the relationship between women’s passionate love and men’s relationship quality (Hendrick et al. 1988) by (1) specifying which type of passion predicts positive relational outcomes, (2) replicating this effect in both men and women, and (3) controlling for the contribution of one’s own passion. Our findings suggest that partners are not necessarily matched in terms of predominant type of passion, providing little support for the homogamy hypothesis (Hahn and Blass 1997), and that the matching status was not important for relationship quality (despite some marginal effect for some indices of men’s relationship quality). This response pattern contrasts with the findings of previous studies (Davis and Latty-Mann 1987; Morrow et al. 1995) showing how within-couple discrepancies on passionate love predict negative relational outcomes. In fact, we found that highly harmonious men in a relationship with highly obsessive women reported better relationship quality. Hence, the benefits of having homogamous types of passion might be moderated by the type of passion, but only for men. Finally, our findings suggest that types of passion are similarly endorsed by both men and women, and that the intra-individual relations between type of passion and indices of relationship quality are equivalent. Therefore, our conceptualization of romantic passion does not appear to be gender-specific.

Study 3

Studies 1 and 2 revealed that having a harmonious passion toward one’s partner predicts more adaptive relational outcomes in the context of one’s romantic involvement than having an obsessive passion for one’s partner. At this point, one may wonder whether these two very different ways of partaking in a romantic relationship affect the longevity of the relationship over time. The two previous studies revealed nonsignificant to small negative correlations between the passions and relationship length, suggesting that the two types of passion can be experienced at any stage of one’s relationship. However, these studies were transversal and therefore did not examine how the two types of passion are related to relationship continuity (i.e., whether the relationship is still going on or has ended) over time. The purpose of Study 3 was to assess the predictive role of passion as pertains to relationship continuity over a 3-month period. Because of its positive relation to indices of functioning, harmonious passion was expected to promote a lasting relationship. Conversely, because of its associated negative features (e.g., distrust of one’s partner), obsessive passion was expected to facilitate relationship dissolution. Study 3 aimed at testing these predictions, using a 3-month prospective design.

Method

Participants and procedure

Participants were 143 Canadians (120 women, 23 men) in an ongoing romantic relationship. Mean age was 27.30 years (SD = 8.84 years) and 93 % of participants were French Canadians. The average relationship length was 4 years and 8 months (SD = 5 years and 9 months). Participants were workers (55.2 %), students (32.2 %) or other (e.g., unemployed; 12.6 %).

Participants were recruited on the Facebook website through an advertisement targeting individuals currently involved in a romantic relationship. People interested in taking part in the study were directed to an online survey website that contained the questionnaire. Participants were invited to provide their email address for a follow-up study. A total of 322 participants completed the first questionnaire, accepted to be contacted again for the follow-up study, and provided a valid email for that purpose. These participants were contacted 3 months later and 44 % (n = 143) of them completed the follow-up questionnaire in which they were asked whether they were still in the same romantic relationship or not.Footnote 4 The choice of a 3-month interval was based on prior research by Lopez et al. (2006) who used a similar time lag to predict relationship continuity among young couples.

Measures

The questionnaire at Time 1 contained shorter versions of the RPS and the PRQCI to increase participation rate in the web survey. Information on the relationship (i.e., relationship length, whether the partners lived together, etc.) along with demographic information (age, gender, etc.) were also collected at Time 1. The questionnaire at Time 2 contained questions about whether the participants were still involved in the same romantic relationship or not.

Harmonious and obsessive passions

Harmonious and obsessive passions were measured with the twelve-item version of the RPS (α = .85 and .79 for harmonious and obsessive passions respectively).Footnote 5

Relationship quality

We used a short version (i.e., one item for each of the six subscales) of the PRQCI described in the previous studies. These six items were chosen because they had the highest correlation (r ranging from .86 to .98) with the total score of their respective subscale, as revealed by a pilot study. The items were aggregated into a global relationship quality score (α = .86).

Results and discussion

Preliminary statistics

After screening the data, we performed a MANOVA which led to a significant Wilks (λ [4,143] = .84; p < .01). Univariate tests revealed that women (M = 5.65) scored higher than men (M = 5.12) on harmonious passion (F [1, 142] = 6.53, p < .05), although this effect was small in magnitude (R 2 = .04). Nevertheless, gender was controlled for in further analyses. Correlational analyses revealed a nonsignificant correlation (r = .11, p = .178) between obsessive and harmonious passion. In addition, relationship length was unrelated to both harmonious and obsessive passions.

Prediction of continuity of relationship

A hierarchical regression analysis was carried out to determine the extent to which harmonious and obsessive passion could predict relationship continuity 3 months later. Because we wanted to test for the contribution of types of passion over and beyond the role of control variables such as relationship quality and gender, these latter variables were entered at Step 1 of the regression analysis whereas the two types of passion were entered at Step 2. The dependent variable was relationship continuity 3 months later (0 = the relationship has ended; 1 = the relationship is still going on).Footnote 6 The results appear in Table 5. It can be seen that at Step 1, relationship quality at Time 1 (β = .25, t [139] = 3.04, p = .003), and gender (0 = female, 1 = male; β = −.16, t [139] = −1.96, p = .052) predicted relationship continuity at Time 2. At Step 2, when the two types of passion were entered in the regression equation, initial relationship quality (β = .06, t [137] = .473, p = .637) and gender (β = −.08, t [137] = −.92, p = .360) were no longer close so significance. More importantly, harmonious passion at Time 1 was a positive and significant predictor (β = .31, t [137] = 2.58, p = .011) of relationship continuity at Time 2 whereas obsessive passion at Time 1 was a negative and marginally significant predictor of this variable (β = −.15, t [138] = −1.79, p = .076). In addition, results revealed that the Step 1 model (i.e., with relationship quality and gender as the only predictors) accounted for 9 % of the variance in relationship continuity. However, when the two types of passion were added (Step 2 model), the amount of explained variance increased by 7 %, an addition that was statistically significant (p = .006). Hence, the two types of passion are important predictors of relationship continuity that explain unique and significant variance in this outcome.

Overall, the results of Study 3 revealed that the stronger individuals’ harmonious passion toward their partner was, the more likely they were to still be involved in a romantic relationship with the same partner 3 months later. The opposite pattern was obtained for obsessive passion. Importantly, these results were obtained over and beyond the contribution of initial relationship quality at Time 1 and participants’ gender. These results suggest that, over time, the decision to pursue a romantic relationship has to do with whether passion is more harmonious or more obsessive. Hence, having a strong harmonious passion and a weak obsessive passion for one’s partner is strongly predictive of relationship stability.

General discussion

The present series of studies aimed at examining how the two types of romantic passion would relate to indices of relationship quality. As the results of Study 1 revealed, harmonious passion was positively and strongly associated with various dimensions of relationship quality, whereas obsessive passion was positively associated with commitment and feelings of love, unrelated to satisfaction, intimacy, and sexual passion, and negatively associated with trusting one’s partner. Study 2 used a dyadic approach and replicated the findings of Study 1. In addition, the results revealed that one’s passion can also affect partner’s outcomes. Specifically, men’s harmonious passion significantly and positively predicted women’s satisfaction, intimacy, and sexual passion, over and beyond women’s own passions. Interestingly, women’s sexual passion also decreased with men’s obsessive passion, such that the more obsessive men reported being toward their partner, the less sexually passionate women reported the relationship to be. For men, only the satisfaction dimension was significantly and positively predicted by women’s harmonious passion, over and beyond the contribution of their own passion. Moreover, based on their predominant type of passion, we found that matching status was not important for predicting relationship quality. In addition, we found no gender differences in levels of harmonious and obsessive passion or in correlational patterns between types of passion and relationship quality, suggesting that our conceptualization of romantic passion is not gender-specific. Finally, using a prospective design, Study 3 revealed that relationship stability over a 3-month period was predicted by high harmonious passion and low obsessive passion. These results are coherent with findings in other domains (e.g., Pelletier et al. 2001; Vallerand et al. 1997) showing that self-determined and controlled types of motivation respectively predict activity persistence and drop-out. In sum, the findings obtained in this set of studies supported a bidimensional conceptualization of romantic passion based on the DMP (Vallerand 2010; Vallerand et al. 2003), which provides the literature on romantic passion with a unique, motivational perspective on passion.

On the bidimensional conceptualization of passion

The present findings have important implications for the Dualistic Model of Passion (Vallerand et al. 2003; Vallerand 2008). First, they support the bidimensional conceptualization of passion in the domain of romantic relationships by showing that harmonious and obsessive romantic passions are distinct constructs and are differently associated with relational outcomes. Second, previous studies on passion toward activities (Séguin-Lévesque et al. 2003; Vallerand et al. 2003, 2006, 2007) showed that harmonious passion contributes positively to individual adjustment and well-being, whereas obsessive passion either does not contribute or contributes negatively to adjustment and well-being. Our findings support and extend this response pattern as harmonious passion was associated with more positive relational outcomes than obsessive passion. Harmonious passion might therefore be indicative of a healthy, high-quality relationship that sustains over time, whereas obsessive passion produces a much fuzzier picture, because it is associated with both positive (e.g., feelings of love and commitment) and negative (e.g., distrust) outcomes. Finally, our findings are consistent with Vallerand et al.’s (2003) conclusion that obsessive passion entails a rigid persistence toward the activity. Here, obsessive romantic passion predicted commitment and love in a relationship that did not provide satisfaction, intimacy, or trust. One can wonder how obsessive passion could possibly entail a rigid persistence in the relationship and still lead to the dissolution of the relationship over time (Study 3). A possible explanation is that one’s partner’s obsessive passion and its associated negative features (e.g., lack of positive emotions and vitality displayed when spending time with partner; Ratelle 2002) might eventually drive one toward the dissolution of the relationship. Another plausible explanation is that individuals who have an obsessive passion stick to their unsatisfying relationship until they find a (seemingly) better alternative partner. These hypotheses would deserve investigation in future research.

In addition, our findings suggest that our conceptualization of romantic passion would apply equally well to men and women, although previous research revealed controversial findings as to whether men and women experienced similar levels of passion (using measures of passion, passionate love, or Eros; see Fehr and Broughton 2001). Study 2 showed that, overall, men and women reported equivalent mean levels of both harmonious and obsessive passion toward their romantic partner. This implies that men and women might not differ in how or the extent to which they internalize the romantic partner in their identity. However, there is an indication that men’s representations of harmonious and obsessive passion overlap more than those of women. Nevertheless, these findings should be interpreted with caution until they can be replicated. Moreover, in line with previous research that reported similar correlations between passionate love (Eros) and satisfaction for men and women (e.g., Davis and Latty-Mann 1987; Hendrick et al. 1988), we found that, for both men and women, harmonious passion predicted positive indices of relationship quality while obsessive passion predicted higher commitment and feelings of love, and, for women, intimacy. The only exception was the correlation between harmonious passion and sexual passion, which was stronger for men. Hence, we may conclude that harmonious and obsessive romantic passions are not gender-specific.

On the perspective of passion and passionate love

Our conceptualization of passion adds to the perspective on passionate love the notion that passion is a bidimensional construct. Distinguishing between harmonious and obsessive passion is important because it improves our understanding of the relational experiences, both positive and negative, in ongoing, reciprocal relationships. When passion is harmonious, individual cognitive and affective functioning is enhanced, and the various dimensions of relationship quality can thrive. Alternatively, obsessive passion is associated with decreased affective and cognitive functioning, which might be precisely what prevents individuals from experiencing relationship quality. According to some relational scholars (e.g., Baumeister et al. 1993; Hatfield and Rapson 1993b, 2000; Hatfield and Walster 1978), passionate love leads to positive consequences only when love is reciprocated and to negative consequences when unreciprocated. There would therefore be a contingency between the reciprocity of love and the valence of outcomes. Instead, our conceptualization of passion proposes that the valence of associated outcomes depends on the way the partner has been internalized within identity and the resulting passion: positive outcomes result largely from a harmonious passion whereas less positive (or even negative) outcomes result from an obsessive passion. This distinction provides a more refined prediction of both positive and negative experiences reported by individuals within an ongoing passionate romantic relationship.

A general assumption in the literature on romantic passion and love is that passionate love characterizes the onset of the relationship although controversial findings exist (e.g., Acker and Davis 1992; Tucker and Aron 1993; see Hatfield and Rapson 1993c). In the present research, we found that harmonious and obsessive passions were generally not significantly correlated or only slighly negatively related with relationship length. These findings are interesting given that across the three studies the average relationship length was more than 3 years. Furthermore, results were consistent with Hendrick and Hendrick’s (1993) proposition that passionate love (Eros) plays a part in both relationship development and maintenance (see also Noller 1996; Sternberg 1986). In line with the DMP, we view the persistence of passion for the romantic partner as a function of value placed in the relationship, love for the partner, and personal investment in the relationship with the partner and not simply elapsed time. Hence, to the extent that people love their partner, evaluate their relationship as important, and invest time and energy in it, we believe that passion, either obsessive or harmonious, will be maintained.

Although social scientists do not agree on the exact nature of the relationship between love and sex, Western culture seems to associate sexuality with at least one type of love, passionate love (see Aron and Aron 1991). In fact, a review by Regan (2000a) illustrated how passionate love has often been conceptualized as containing “an interesting mixture of sexual elements” (p. 245). Some support was even provided for the association between passionate love and the frequency of sexual contacts (Aron and Henkemeyer 1995), although this does not necessarily provide support for the health of a couple’s sexual life. By distinguishing between harmonious and obsessive passion, we were able to specify exactly how passion is associated with sexuality. Specifically, we found that sexual passion is associated with the healthier type of romantic passion, namely harmonious passion. This finding is consistent with studies reporting that, for most individuals, sexuality is more appropriate within the boundaries of a committed and loving relationship (see Regan 2000a). In fact, intimacy has often been thought of as a prerequisite to sexual passion (Love and Brown 1999). Furthermore, our findings concur with previous research reporting a positive relation between sexuality and relationship satisfaction (e.g., Regan 2000b). Because harmonious passion is strongly associated with relationship satisfaction, it makes sense that sexuality flourishes more in the presence of harmonious (than obsessive) passion.

Despite the innovative nature and potential contributions of this set of studies, it is important to consider their methodological limitations when interpreting the results. A first limitation pertains to the correlational nature of the studies, which makes it impossible to formulate causal interpretations of the relations among the variables assessed in these studies. Second, samples for each study were composed mainly of young, heterosexual adults from student populations and might not be representative of all individuals engaged in romantic relationships. Third, all measures were self-reported, which could have induced social desirability concerns. Because social desirability was not significantly correlated with either harmonious or obsessive passions in previous studies (e.g., Rousseau et al. 2002), we believe that the participants’ responses were fairly accurate and closely reflect their true perceptions. Nevertheless, the role of social desirability in relationship should be assessed in future research. Fourth, we have found the relationship between the two types of passion to vary in magnitude across the three studies. It is not clear at this point why such differences were found. Future research is needed in order to better understand why such differences take place and their functionality if any. Finally, these findings need to be replicated using a longitudinal design that follows partners over different phases of the relationships. Such procedures would allow us to test hypotheses regarding the pre-requisites for the development of each type of passion.

In sum, the present findings bring support for the bidimensional conceptualization of romantic passion proposed by the DMP and they provide the literature on romantic relationships with a new and innovative theoretical framework with which to study relational dynamics. The importance of our findings lies in the usefulness of distinguishing between harmonious and obsessive passions to understand relational outcomes and in the potential to yield new research avenues. This set of studies provides information on the adaptive and maladaptive aspects of passion, showing how passion can enhance or undermine own and partner’s relationship quality as a function of passion type. Hopefully, future research will allow us to gain a better understanding of the antecedents and consequences of harmonious and obsessive romantic passion as well as the nature of the psychological processes involved in individual and relational outcomes of romantic engagement.

Notes

The passion subscale of the PRQCI (Fletcher et al. 2000) is composed of items reflecting sexuality (e.g., “Our relationship is sexually passionate”). For this reason, we refer to it as a measure of sexual passion.

Because of the interdependent nature of couple data, we used a dyad structure (Kenny et al. 2006) where women’s and men’s data are entered under a same dyadic unit to control for shared variance. Each case or line of data therefore represents a couple in which partners are nested.

Mean levels of harmonious passion were 5.47 and 5.54 and mean levels of obsessive passion were 3.97 and 3.74 for men and women, respectively.

Analyses revealed no significant differences between this subset and the rest of the sample on harmonious passion, obsessive passion, relationship quality, age, and gender of participants at Time 1. However, participants who took part in the follow-up study had a shorter relationship length (M = 51.58 months) at Time 1, F(1, 320) = 4.63, p < .05, than participants who did not complete the follow-up (M = 70.91 months), although the magnitude of this difference was small (R 2 = .01).

In a pilot study, the 12-item and 14-item version of the RPS were shown to be highly correlated (r = .87 for the harmonious passion subscale; r = .84 for the obsessive passion subscale) and were shown to lead to similar results in terms of their associations with various outcomes (e.g., relationship quality, rumination, internalization of partner in the self, etc.).

Of the 143 participants, 7.7 % (n = 11) of them were no longer involved in the same romantic relationship at Time 2. These participants did not have a different relationship length at Time 1 than those who were still involved in the same relationship at Time 2 (F [1, 142] = 2.13, p = .15, R 2 = .01).

References

Acker, M., & Davis, M. H. (1992). Intimacy, passion, and commitment in adult romantic relationships: A test of the triangular theory of love. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 9, 21–50.

Aron, A., & Aron, E. N. (1991). Love and sexuality. In K. McKinney & S. Sprecher (Eds.), Sexuality in close relationships (pp. 25–48). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Aron, A., & Henkemeyer, L. (1995). Marital satisfaction and passionate love. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 12, 139–146.

Aron, A., & Westbay, L. (1996). Dimensions of the prototype of love. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 535–551.

Baillargeon, J., Dubois, G., & Martineau, R. (1986). Traduction française de l’Échelle d’ajustement dyadique. [French translation of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale]. Canadian Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 18, 25–34.

Baumeister, R. F., Wotman, S. R., & Stillwell, A. M. (1993). Unrequited love: On heartbreak, anger, guilt, scriptlessness, and humiliation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 377–394.

Davis, K. E., & Latty-Mann, H. (1987). Love styles and relationship quality: A contribution to validation. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 4, 409–428.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2002). Handbook of self-determination research. Rochester, NY: The University of Rochester Press.

Fehr, B., & Broughton, R. (2001). Gender and personality differences in conceptions of love: An interpersonal theory analysis. Personal Relationships, 8, 115–136.

Fletcher, G. J. O., Simpson, J. A., & Thomas, G. (2000). The measurement of perceived relationship quality components: A confirmatory factor analytic approach. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 340–354.

Gao, G. (2001). Intimacy, passion, and commitment in Chinese and US American romantic relationships. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 25, 329–342.

Hahn, J., & Blass, T. (1997). Dating partner preferences: A function of similarity of love styles. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 12, 595–610.

Hatfield, E., Pillemer, J. T., O’Brien, M. U., & Le, Y. L. (2008). The endurance of love: Passionate and companionate love in newlywed and long-term marriages. Interpersona, 2, 35–64.

Hatfield, E., & Rapson, R. L. (1993a). Historical and cross-cultural perspectives on passionate love and sexual desire. Annual Review of Sex Research, 4, 67–97.

Hatfield, E., & Rapson, R. L. (1993b). Love and attachment processes. In M. Lewis & J. M. Haviland (Eds.), Handbook of emotion (2nd ed., pp. 654–662). New York: Guilford Press.

Hatfield, E., & Rapson, R. L. (1993c). Love, sex, and intimacy: Their psychology, biology, and history. New York: Harper Collins College Publishers.

Hatfield, E., & Rapson, R. L. (2000). Love and attachment processes. In M. Lewis & J. M. Haviland-Jones (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (pp. 595–604). New York: Guilford Press.

Hatfield, E., & Sprecher, S. (1986). Measuring passionate love in intimate relationships. Journal of Adolescence, 9, 383–410.

Hatfield, E., & Walster, G. W. (1978). A new look at love. Lantham, MA: University Press of America.

Hendrick, C., & Hendrick, S. S. (1993). Lovers as friends. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 10, 459–466.

Hendrick, C., Hendrick, S. S., & Adler, N. L. (1988). Romantic relationships: Love, satisfaction, and staying together. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 980–988.

Kenny, D. A., Kashy, D. A., & Cook, W. L. (2006). Dyadic data analysis. New York: Guilford Press.

Kim, J., & Hatfield, E. (2004). Love types and subjective well-being. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 32, 173–182.

Lafrenière, M.-A. K., Jowett, S., Vallerand, R. J., Donahue, E. G., & Lorimer, R. (2008). Passion in sport: On the quality of the coach-player relationship. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 30, 541–560.

Lafrenière, M.-A. K., Vallerand, R. J., Donahue, R., & Lavigne, G. L. (2009). On the costs and benefits of gaming: The role of passion. CyberPsychology and Behavior, 12, 285–290.

Lopez, F. G., Fons-Scheyd, A., Morua, W., & Chaliman, R. (2006). Dyadic perfectionism as a predictor of relationship continuity and distress among college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53, 543–549.

Love, P., & Brown, J. T. (1999). Creating passion and intimacy. In J. Carlson & L. Sperry (Eds.), The intimate couple (pp. 55–65). Philadelphia, PA: Brunner/Mazel.

Mageau, G. A., Vallerand, R. J., Charest, J., Salvy, S.-J., Lacaille, N., Bouffard, T., et al. (2009). On the development of harmonious and obsessive passion: The role of autonomy support, activity valuation, and identity processes. Journal of Personality, 77, 601–645.

Morrow, G. D., Clark, E. M., & Brock, K. F. (1995). Individual and partner love styles: Implications for the quality of romantic involvements. Journal of Social and Personal relationships, 12, 363–387.

Murray, S. L., & Holmes, J. G. (1997). A leap of faith? Positive illusions in romantic relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23, 586–604.

Noller, P. (1996). What’s this thing called love? Defining the love that supports marriage and family. Personal Relationships, 3, 97–115.

Pelletier, G. L., Fortier, M. S., Vallerand, R. J., & Brière, N. M. (2001). Associations between perceived autonomy support, forms of self regulation, and persistence: A prospective study. Motivation and Emotion, 25, 279–306.

Philippe, F., & Vallerand, R. J. (2007). Prevalence rates of gambling problems in Montreal, Canada: A Look at old adults and the role of passion. Journal of Gambling Studies, 23, 275–283.

Philippe, F., Vallerand, R.J., & Lavigne, G. (2009). Passion does make a difference in people's lives: A look at well-being in passionate and non-passionate individuals. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 1, 3–22.

Philippe, F., Vallerand, R. J., Houlfort, N., Lavigne, G. L., & Donahue, E. G. (2010). Passion for an activity and quality of interpersonal relationships: The mediating role of emotions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98, 917–932.

Ratelle, C. F. (2002). Une nouvelle conceptualisation de la passion amoureuse. [A new conceptualization of romantic passion]. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Quebec in Montreal, Montreal, QC, Canada.

Reeve, J. (1997). Understanding motivation and emotion (2e.). Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace.

Regan, P. C. (2000a). Love relationships. In L. T. Szuchman & F. Muscarella (Eds.), Psychological perspectives on human sexuality (pp. 232–282). New York: Wiley.

Regan, P. C. (2000b). The role of sexual desire and sexual activity in dating relationships. Social Behavior and Personality, 28, 51–60.

Rip, B., Fortin, S., & Vallerand, R. J. (2006). The relationship between passion and injury in dance students. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science, 10, 14–20.

Rousseau, F. L., Vallerand, R. J., Ratelle, C. F., Mageau, G. A., & Provencher, P. J. (2002). Passion and gambling: Validation of the gambling passion scale (GPS). Journal of Gambling Studies, 18, 45–66.

Séguin-Lévesque, C., Laliberté, M. L., Pelletier, L. G., Vallerand, R. J., & Blanchard, C. (2003). Harmonious and obsessive passions for the Internet: Their associations with couples’ relationships. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 33, 197–221.

Spanier, G. B. (1976). Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 38, 15–28.

Sternberg, R. J. (1986). A triangular theory of love. Psychological Review, 93, 119–135.

Sternberg, R. J. (1997). Construct validation of a triangular love scale. European Journal of Social Psychology, 27, 313–335.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Tucker, P., & Aron, A. (1993). Passionate love and marital satisfaction at key transition points in the family life circle. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 12, 135–147.

Vallerand, R. J. (2008). On the psychology of passion: In search of what makes people’s lives most worth living. Canadian Psychology, 49, 1–13.

Vallerand, R. J. (2010). On passion for life activities: The dualistic model of passion. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 42, pp. 97–193). New York: Academic Press.

Vallerand, R. J., Blanchard, C., Mageau, G. A., Koestner, R., Ratelle, C. F., Léonard, M., et al. (2003). Les passions de l’âme: On obsessive and harmonious passion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 756–767.

Vallerand, R. J., Fortier, M. S., & Guay, F. (1997). Self-determination and persistence in a real-life setting: Toward a motivational model of high school dropout. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 1161–1176.

Vallerand, R. J., Ntoumanis, N., Philippe, F., Lavigne, G. L., Carbonneau, N., Bonneville, A., et al. (2008). On passion and sports fans: A look at football. Journal of Sport Sciences, 26, 1279–1293.

Vallerand, R. J., Rousseau, F. L., Grouzet, F. M. E., Dumais, A., & Grenier, S. (2006). Passion in sport: A look at determinants and affectives experiences. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 28, 455–478.

Vallerand, R. J., Salvy, S. J., Mageau, G. A., Denis, P., Grouzet, F. M. E., & Blanchard, C. B. (2007). On the role of passion in performance. Journal of Personality, 75, 505–533.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a doctoral scholarship from FCAR awarded to the first author. We thank Pierre Provencher, Julie Charest, Julie Coiteux, Chantale Bélanger, Chantale Ouellet, Mariane Dupuis, and David Michaliszyn for their valuable assistance in collecting and entering the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Studies 1 and 2 were part of the first author’s doctoral dissertation.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ratelle, C.F., Carbonneau, N., Vallerand, R.J. et al. Passion in the romantic sphere: A look at relational outcomes. Motiv Emot 37, 106–120 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-012-9286-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-012-9286-5