Abstract

The managerial turn in academia is currently broadly discussed. Based on empirical data gathered from a sample that includes all German universities, we can give a broad and fine-grained account of this turn. What we can clearly see is that whole new categories of administrative management positions have been created over the last years. Furthermore, within the non-academic staff we can see a profound restructuration. Lower-level positions like those for clerical work decreased, while higher-level positions in the administration increased. However, and in contrast to studies of countries, we do not observe a general shift from academic to non-academic positions. In addition to the statistical analysis of survey data and personnel data, we conducted seventy in-depth interviews with heads of administrative management units, in particular those being created over the last two decades, for example, on quality control, technology transfer, and career service. Although we clearly see important changes indicating a managerial turn in higher education, core characteristics of a professional organization whose basic processes are ultimately controlled by academics and not by administrators or managers have been retained. These findings call for further cross-national research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In his seminal book The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business, Alfred D. Chandler, Jr. gave us some central accounts of the rise and institutionalization of management in the business sector through his analysis of changing practices in a variety of firms over time (Chandler 1977). According to him, between the mid-19th and early 20th century the sheer growth of firms and the increasing complexity of both internal and external environments, in particular the market, moved firm owners in the United States away from the practice of guiding and controlling their firms and their workers. Family businesses became companies led by managers and the ownership of the firm became separated from its management. With the advent of the salaried manager and related managerial hierarchies carrying out the task of administrative coordination a new professional group emerged, one which became increasingly important for the individual firm and society at large. Similar developments occurred in Europe, though mostly after a considerable time-lag (Chandler 1977: 498–500; for Germany, see also Kocka 1969).

There has been a long scholarly debate on Chandler’s accounts, and despite praise for the originality, depth and richness of his book, sociologists often doubt central aspects of his analysis. In particular, the finding that strong efficiency gains are associated with the rise of industrial management is questioned and, in contrast to Chandler’s main focus on the internal dynamics of the economic sector, a stronger role is assigned to external political and legal forces (Fligstein 1990). We do not seek to contribute directly to this debate nor will we cover the whole elaboration on the structure of the modern multiunit enterprise that is so central to Chandler’s work. Instead, we draw on only one of Chandler’s central and rather uncontested insights—the relationship between the complexity of an organization and its environments and the rise of the management profession—as a stepping-stone for making sense of the managerial turn in higher education that we are currently witnessing in very different national systems.

The driving forces that contribute to the growing complexity of universities and their environments can be observed at three different levels, on which we have reflected elsewhere (Krücken 2011). At the macro-level of society we can see the increasing inclusion of persons, subjects of study, and university missions (Schofer and Meyer 2005; Frank and Gabler 2006). The second level where we can find substantial changes is at the level of university governance (Paradeise et al. 2009). In most higher education systems in Continental Europe, New Public Management reforms have put into question the traditional modes of governance and the interplay between the state, the academic profession and other actors in society (Teichler and Höhle 2013). In this process, new actors such as accreditation and evaluation bodies or university boards have been established and play an increasing important role. A third level where profound changes can be observed is at the university level itself. The university as an organization is transforming into an organizational actor, i.e. an integrated, goal-oriented, and competitive entity that increasingly behaves like a strategic actor and less like a loosely coupled system (Krücken and Meier 2006; de Boer et al. 2007).

Together, these transformations contribute to an increase in complexity through the multiplication of elements relevant to the system and the way they are linked. Furthermore, they are strongly interrelated to the diffusion and entrenchment of management capacities within universities. Similar to its role in the early phase of industrial management, the United States can be regarded as a forerunner of the managerial turn in the higher education sector with respect to what we have been observing in Europe and other parts of the world over the last 10–20 years (Krücken 2011: 16–18). The advent of new managerialism within the higher education sector as an ideology has not only altered the ways of planning, funding, evaluating research and teaching but has also had far-reaching implications for the formal organization of institutional management and administrative realms of universities (Amaral et al. 2003; Deem et al. 2007; Whitchurch 2008). However, organizational and occupational changes within institutional management and administration are under-researched areas (Shelley 2010: 41; Szekeres 2004).

Therefore, this paper looks at the transformation of university organization in Germany and its implications for university management and administration. Although Germany has been characterized as a late-comer in adopting new public management reforms, there is no doubt that comprehensive reforms have been introduced over the last decade (Schimank 2005; Schimank and Lange 2009; Lange and Krücken 2011). We assume that the development of management capacities plays a pivotal role in the current processes of change. More precisely, our research on “The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in Higher Education”, to refer to Chandler’s book title, is guided by three assumptions for which we seek empirical evidence from an in-depth analysis of the German system.

The first assumption is that the development of management capacities goes hand in hand with the more intensive recruitment of specialized management staff and thus with a growth in non-academic staff. Concurrently, we would expect a relative decline of academic staff. We thus assume that the managerial turn in higher education is reflected in staff numbers.

The second assumption is related to the staff hired in the process of the managerial turn. We assume that the managerial turn in higher education is accompanied by strong recruitment of people from the private sector. Since companies have accumulated a lot of management expertise over time, it can be assumed that the staff required to manage universities will primarily be recruited from the private sector.

Third, we assume that middle managers have strong ambitions to increase their amount of control, particularly vis-à-vis academics. Such ambitions shape the identity of middle managers as central parts of the new, managed university organization. As a result, the patterns of relationships between middle management and academic staff are rife with conflicts.

We make use of several different data sources in order to answer our main research questions. The data were gathered and interpreted in a research project conducted at the German Research Institute for Public Administration Speyer from April 2007 to December 2010. First, we analyzed quantitative data on the number of non-academic and academic staff from 1992 to 2007 at German universities. Second, using content analysis we analyzed job advertisements in the area of university management in the weekly newspaper Die Zeit from the years 1997 to 2006. Third, our paper draws on the results of two surveys of senior university administrators that we conducted in 2008 and 2009. One survey was aimed to interview all heads of administration at German universities (n=153; Response rate 57 %). The other survey covered the working situation of heads of administrative units working in the areas of International Affairs, Executive & Continuing Education, Career Service, Quality Management, Technology Transfer, and Marketing & Public Relations (n=454; Response rate 40 %).Footnote 1 Fourth, we conducted seventy in-depth interviews with representatives from our two survey samples. Taking these different data sources together, we believe we have constructed a unique database for the analysis of the managerial turn in higher education in one country.

Taken together, we find that none of the three research assumptions stated above can be fully confirmed empirically. Although there is a trend towards a more managerial organization of German universities, this trend does not imply the adoption of the organizational and personnel structures of the private sector. Although we provide evidence of a robust trend of managerialization, this trend is buffered by basic tenets of academia that at least in the German context we analyzed are still shaping the organization of work in higher education institutions. Rather, organizational and occupational change is characterized by the development of distinct areas and specialized expertise in university management, but not by management as an overall profession that supersedes the academic profession. In this regard, the analysis that we present and discuss in more detail in part II provides a more fine-grained view on the process of organizational transformation of universities. Further implications of our research will be discussed in the concluding part III.

Referring to Chandler (1977), we see both parallels and differences between the inception of industrial management in the 19th century and the more recent inception of university management. On the one hand, as in industrial management, there is a clear increase in management tasks that is due to the increased complexity of German universities and their environments. In contrast to industrial management, however, the power of middle managers vis-à-vis other actors in the organization is very limited. Although undoubtedly a managerial turn in higher education has occurred in German universities, core characteristics of a professional organization, whose basic processes are ultimately controlled by academics and not by managers, have been retained.

Empirical Findings

University Management: Expansion of Administrative Staff?

In this section we address our first assumption that the managerial turn in German academia since the 1990s is accompanied by a growing number of non-academic staff as compared to academic staff. Before presenting our results, we will refer to the state-of-the-art in comparative higher education research. It is assumed that the increasing complexity of universities and their environments leads to the specialization of administrative areas of university organization, increased recruitment of higher education professionals and the hybridization of professional roles within universities (Rhoades and Sporn 2002; Gordon and Whitchurch 2010; Shelley 2010).

Some authors argue that academics have increasingly had to take on management tasks and include entrepreneurial goals in their work, in addition to their traditional focus on research and teaching (Deem et al. 2007; Gordon and Whitchurch 2010; Mcfarlane 2011). At the level of the university leadership team, one can observe the establishment of new management roles and the increasing differentiation of functions of new vice-presidents and related staff (Logue 2010; Smith and Adams 2008). In an analysis of the universities belonging to the Association of Commonwealth Universities from the 18th century to the present, Danielle Logue shows that there has been a global expansion of university leadership teams and a continuous incorporation of new missions through the creation of new positions (Logue 2010). In Germany, amendments to the state laws concerning universities since 1998 have led to the strengthening and differentiation of the functions of university leadership (Hüther 2010).

Furthermore, management reforms and new external requirements have led to the establishment of new organizational units at the level of the university administration. In the German context, university management and administration have traditionally been divided into the following areas: 1. Academic university management (President/rector, vice-presidents, deans, heads of institutes, etc.): this includes all leading managerial positions within the university that are held by academics, typically only for a limited period of time. 2. Administrative university management (senior administrative managers, heads of offices and service facilities, etc.): this includes full-time administrative management staff with responsibility for staff, organization and resource administration within a specific area.Footnote 2 3. Administrative staff: this includes all persons working as support staff in administrative units without managerial competencies.

However, with the creation of new organizational units and management positions there is a growing group of staff members located at the interface between administration, academics and university leadership. This category mostly includes staff responsible for a specific project, subject or instrument within the university administration. These newly created administrative units and management positions increasingly include areas such as degree program development, quality assurance of teaching and research, and knowledge and technology transfer. As they are much closer to core academic processes, i.e. teaching and research, they differ from traditional administrative units and processes. In this regard, some authors claim that we are observing the development of new professional groups within the university, mostly located at the interface between academics, administration and university leadership. According to these authors, persons working in such units can neither be seen as part of the routine administration nor do they belong to the academic staff (Whitchurch 2004; Klumpp and Teichler 2006; Szekeres 2004; Harman and Stone 2006; Zellweger-Moser and Bachmann 2010).

Thus, the expansion as well as specialization of administrative units and positions reflects the increasing external expectations and new requirements with which universities are confronted. The establishment of new management functions implies comprehensive processes of re-organization and coordination processes both at the leadership level and at the level of administrative management. Thereby, the traditional organizational configurations of universities are called into question. In the German case, the traditionally strict separation of central administration and academic units has become more fluid. But to what extent do these organizational changes in universities also correspond with changing recruitment practices and the reconfiguration of staff?

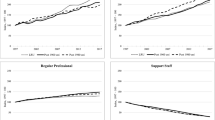

A first impression can be obtained from the analysis of job advertisements for qualified positions in administrative university management that appeared in the weekly newspaper Die Zeit from 1999 to 2006. Especially for senior university administrator and manager positions, the number of jobs advertised every year has grown continuously, from 92 (1999) to 169 (2006) (see Fig. 1).

Our analysis of the job descriptions also shows that over time a stronger differentiation has been made according to specific areas of work and more distinct job descriptions have evolved. At the end of the 1990s, universities were still generally looking for senior administrators. Contrary to this, current advertisement texts describe more specific positions, for example, in research management, quality assurance or career service. This goes hand in hand with an increasingly more precise description of the specific work and competencies demanded. Job advertisements for quality managers, for example, increasingly include more precise and elaborated job profiles (e.g. development of concepts, implementation of evaluations, development of a quality management system, academic controlling) as well as enumerating specific competencies required (especially work experience in the area of quality management, knowledge of evaluation and accreditation processes, statistical expertise and a profound knowledge of the German university system and its relevant environments).

An important aspect discussed in comparative university research is the assumption of a clear rise in administrative and management staff at universities. This assumption was also central to our research. Studies on staff configurations in Finnish, Norwegian and American universities show that managerial reforms in the university sector and the formation of new occupational groups at universities correspond with a growth in non-academic staff and a simultaneous decrease in academic staff.

Rhoades and Sporn (2002) examined the relationship between academic and non-academic staff in the USA from 1976 to 1995. They found that the proportion of academic staff as part of overall staff at American universities dropped from 69.3 % to 61.0 % during this period, whereas the proportion of non-academic staff increased from 30.7 % to 39 %. The increase in non-academic staff in this case was mainly due to the rise in “managerial professionals” (highly qualified administrative staff in research and teaching related areas, i.e. the group of persons being sought in the German job advertisements mentioned above), whose proportion among all employees rose from 19 % to almost 30 % from 1976 to 1995. Following these data, Rhoades and Sporn assume that academic work is no longer carried out only by the individual academic. Instead, academic work is increasingly influenced by many different players, especially “managerial professionals.”

More recent numbers seem to confirm this trend for the USA. A study by the Goldwater Institute (2010) shows that from 1993 to 2007 the number of full time administrators per 100 students at 198 private and public Ph.D. granting universities grew by 39 %, whereas the number of academic staff rose by only 18 %. Financial expenditures developed in a similar fashion: In the same period expenditures for administration increased by 61 %, whereas expenditures per student for teaching rose by only 39 %.

Gornitzka and Larsen (2004) show that in Norway there was a general increase in university staff from 1987 to 1999, by 56 % for academic staff and 66 % for non-academic staff. The increase in non-academic staff was caused in particular by recruitment of so-called “higher administrative staff,” whose numbers rose by 215 % between 1987 and 1999. At the same time, the group of people who were lower qualified office employees decreased by 28 % (Gornitzka and Larsen 2004: 458). The proportion of highly qualified administrative staff thus rose from about a third of all non-academic staff in 1987 to about three-quarters in 1999.

Similar developments have also been observed in Finland. Visakorpi (1996) describes a strong increase in non-academic staff compared with academic staff. This was caused by a growing percentage of highly qualified non-academic staff. Between 1989 and 1992 this group grew by 39 %, whereas the percentage of less qualified technical staff and administrative staff decreased by 11.8 %. But to what extent can similar developments be found at German universities?

For our analysis we used yearly data from 1992 to 2007, which was obtained from the ICE-Land database of the German Higher Education Information System (HIS), a database, which assembles all data from official higher education statistics. It can be shown that the total number of persons employed at German universities in the past few years has clearly increased (see Tables 1 and 2). This increase—unlike the developments in some other countries as described above—has particularly been caused by a growth in academic staff, or, to be more precise, academic staff in arts and sciences financed by third-party funding as well as teaching staff for specific tasks. It is particularly interesting to see that the strongest growth rate by far was for faculty whose professorship was not financed directly by the state but through third-party funding (see Table 1).

As Table 2 illustrates, we can see a strong growth of academic staff (+28.3 %) between 1992 and 2007, while in the case of non-academic staff we observe a decrease −4.6 %.

If we look at the relationship of non-academic staff to academic staff at German universities, this shifted from 42.9 % non-academic staff versus 57.1 % academic staff in 1992 to 35.8 % non-academic staff versus 64.2 % academic staff in 2007.

However, in a more fine-grained analysis a shift in the composition of non-academic staff with regard to their formal educational level is evident. Members of non-academic staff at German universities are part of the civil service.Footnote 3 Recruitment, salaries and human resource development of non-academic staff at universities are based on rigid regulations within public service law. Status, career and remuneration schemes for civil service sector employees are determined according to tasks and functions. Overall, four status groups are generally distinguished for positions in civil service in Germany: lower level, middle level, upper grade level and higher grade level. Entry into each level is based on minimal educational qualifications. For positions within the higher grade of non-academic staff a university degree is a formal prerequisite; for positions within the upper grade level at least a degree from a polytechnic school is required.

In the period from 2002 to 2007 there was a disproportionately strong increase in the number of positions within the higher and upper grade non-academic staff. The numbers of higher grade staff increased during this period by 20.9 %, while upper grade staff increased by 19.5 %. Whereas positions with less formal qualification levels remained relatively constant (middle grade) or significantly dropped (lower grade: −32.0 %). Thus, the status group of higher grade staff compared to staff in the remaining three groups strongly increased between 1992 and 2007 in all areas of non-academic staff.

Of equally high importance is the question of whether the increase of higher grade staff is accompanied by the ‘feminization’ of administrative university management.Footnote 4 Our data on this subject is unequivocal. Between 1992 and 2007, the number of women in the highest status group increased by 148 %, while the number of men increased by only 22.9 %. The strong increase holds particularly true for administrative staff as compared to other areas of non-academic work (technical staff, library staff and other staff). In general, it is evident that by far the strongest growth rate was among the group of higher grade staff in the administrative area. Between 1992 and 2007, the number of higher grade employees in the administration increased by 90 %, while, for example, the number of maintenance staff in the simple to upper grades decreased by 38.8 %. This development is also reflected in the ratio of higher grade administrative staff to the total non-academic staff. While in 1992, the percentage share of higher grade employees in the administration was 55.3 %, it rose to 67.0 % in 2007. The number of women in the group of higher grade staff administrative area between 1992 and 2007 in absolute numbers increased by 1,771, while the number of men only increased by 808. This implies a ratio of 49 % women in 2007, while in 1992 only 31 % of the higher administrative staff was female. If this trend continues, we assume that in the second decade of the third millennium we will have more women working in higher grade level positions in the German university administration than men, which would be a remarkable change as compared to previous decades.

To summarize, we can conclude that unlike in the USA, Finland and Norway the academic/non-academic ratio of personnel at German universities shifted slightly in favor of academic staff. However, and in accordance with the results from studies in other countries, a clear increase in positions for higher and highly qualified non-academic staff can be noted, particularly in the administrative area and with regard to women in higher education management. At the same time, there was a remarkable decrease in positions requiring lower levels of qualifications, particularly in the area of maintenance and technical services.

The significant rise of highly qualified administrative staff can be seen as a strong indicator of the development of management capacities at German universities. However, at first sight this is not reflected in the quantitative relationship between academic and non-academic staff, mainly for two reasons. On the one hand, the financial support for academic personnel increased over the last years, especially through third-party funding and a variety of political programs that were developed in order to foster research and teaching (Lange and Krücken 2011). On the other hand, there have been cuts through restructuring and outsourcing with regard to non-academic staff requiring lower levels of qualifications. In addition, a further development of management capacities can also be assumed due to the employment of staff in academic positions who, nevertheless, work almost exclusively on administrative tasks. In the survey we conducted among leading staff members in administrative university management at German universities, 20 % of the participants mentioned that they formally worked as part of the academic staff although their job profile corresponded to that of an administrative manager. This result puts our data and their interpretation in perspective. Apparently, the differences to other countries are smaller than at first sight. We assume that the rather high percentage of administrative managers being employed as academic staff is due to the fact that the creation of academic positions within universities is still easier to justify internally than the creation of positions that do not contribute directly to research and teaching.

University Managers: Business Professionals from the Private Sector?

In this section we address the second assumption: that the managerial turn in higher education is accompanied by a strong recruitment of persons from the private sector. Furthermore, the disciplinary background of administrative university managers will be examined, as we expect to see related changes that favor a stronger management or business orientation. As in other public sector institutions, the development of new management capacities in universities is embedded in discourse and policy-making, in which organizational patterns and management instruments from the private sector are strongly emphasized (Kickert 1997; Pollitt and Bouckaert 2000). For university administration in Germany, legal changes in university governance indicate a shift from a bureaucratic model to new public management (Schimank 2005; Schimank and Lange 2009). For the internal university structure this means more emphasis on performance and service processes that are mainly carried out by specialized units. At the same time, the decentralization of administration and the establishment of new positions at the level of departments and research clusters lead to the transformation of the former functions of academic self-administration, which are increasingly carried out by specialized higher education managers.

Here, the establishment of new performance oriented budget systems and the introduction of double-entry accounting, plus the development of extensive evaluation schemes as well as instruments for marketing and strategic development, such as, for example, balanced scorecards, require a wide range of new expertise at universities. Whereas experience in the higher education sector was traditionally a central requirement for leading staff in the university administration, one could assume that the current development of management structures and capacities at German universities also implies a more intensive recruitment of employees with work experience in the private sector.Footnote 5

Empirical studies on management reforms in Great Britain and the USA indicate that recruitment is increasingly oriented toward staff that has formal qualifications in management or work experience outside the university sector, particularly in the private sector (Basnett 2005; Leicht and Fennell 2008: 99; Rhoades 1998; Whitchurch 2004). Furthermore, an increase in professional networks of university managers has been noted in Europe over the past few years. Similar to the USA, where independent professional associations have been established for many areas of university development, professional networks and specialized professional associations in various areas of university management have also emerged in Great Britain, Scandinavian countries and at a European level (Basnett 2005: 100; Pausits and Pellert 2009; Gornnitzka and Larsen 2004: 463; Middlehurst 2004). But what do we observe in the German university sector?

Based on a countrywide survey of 454 administrative university managers in the areas of quality management (for research and teaching), career service, international affairs, continuing education, technology transfer, and marketing & public relations, we are able to give some detailed accounts on the German case. Before dealing directly with the question of whether these administrative university managers come from the private sector, let us first have a look at their academic degrees and experiences.

An academic university degree as well as experience, or at least an affinity to research, is part of the profile of most of the leading employees in administrative university management who took part in our survey. A very heterogeneous academic background was found (see Fig. 2). To focus on the largest and the least directly relevant degree groups: 27 % have a humanities or arts degree, 19 % of the administrative university managers have a background in business administration or economics, and 18 % have one in the social sciences. At the same time, only 4 % have studied law and 5 % administrative sciences. 10 % of those who participated in our survey have an advanced professional management degree (MBA/MPA/MPP) and thus obtained specialized and certified management skills before entering university management.

Here, clear differences are evident in the academic background of personnel in the different areas of administrative university management. Whereas the areas of international affairs and quality management are characterized by the dominance of graduates in the humanities and arts, employees with business or economics degrees are more frequently found in the areas of career service and executive & continuing education.

Our analysis of academic degrees leads us to doubt the existence of a common and generalized understanding of university management that is based on a particular academic background and discipline-specific concepts. In the in-depth interviews we conducted with administrative university managers parallel to our survey, the individuals frequently mentioned that the decision to recruit them was mainly due to their specific expertise and interest in a respective subject area of university management. This is also confirmed by other surveys. A survey of managing directors at the departmental level of German universities, for example, shows that these positions are usually filled with those who have an academic background in one of the discipline(s) of the respective department (Leichsenring 2007). Familiarity with universities as organizations or department-specific knowledge thus appears to be an important, if not a central, selection and recruitment criterion for new positions in administrative university management.

This characteristic affinity of the administrative university managers to their organization and specific areas within the organization can also be seen in two other results of our survey: First, 23.9 % of those who participated have a Ph.D. The percentage of employees with a Ph.D. is even higher in genuinely research and teaching oriented areas of administrative university management, such as technology transfer with 38.6 % and quality assurance with 32.6 %. Thus, many of the interviewees emphasized that their own research experiences were an important criterion for their recruitment into university management.

A second indicator for the affinity of this group of university managers for the university sector is that their career paths are closely connected to academic and higher education institutions. 23.8 % of the administrative managers participating in our survey worked in the same or a similar position in one of the six areas we analyzed immediately before assuming their current position; 24.6 % previously worked in another (non-academic) position in the university sector or other public research organizations (see Fig. 3). Conversely, it is not very common to recruit university managers directly from the private sector. Overall, only 13.1 % in our survey were hired directly from the private sector. In areas with strong connections to the business sector, such as career service, the percentage is clearly higher, but even then it is below one-fourth of the group.

The results of our analysis of the academic backgrounds and previous professional work are different with regard to the heads of the administration at German universities. On the basis of our survey, two characteristics stand out. First, we can see a trend toward more heterogeneous disciplinary backgrounds. Second, we observe a more intense recruitment of those with a degree in business administration or economics. Whereas the percentage of those belonging to this group has increased, the percentage of those with a law or public administration degree has decreased (see Fig. 4). This is at least in part due to changes in the legal framework for public German universities, as in most states a law degree is no longer a formal requirement for access to the highest position in the university administration.

Thus, only 12.8 % of the heads of administration who have been in office for more than 9 years state that they have a background in business administration, management or economics, whereas for those who have taken up office during the past 4 years, 37.3 % have such a business-oriented academic background (see Fig. 4). In addition to this, several more recently appointed heads have graduated in, for example, natural sciences or social and educational sciences contributing to an even more heterogeneous picture.

Furthermore, the career paths of heads of university administration is—similar to that of heads of specialized units as discussed above—characterized by a strong affinity to the organizational field of research and higher education. Most heads of university administration have had substantial work experience in universities, higher education ministries and other institutions of the science system. About 25 % of them worked at another university before assuming their current position and 22.8 % were recruited internally (see Fig. 5).

On average, 26.8 % of the heads of the administration have had professional experience in the private sector before taking up office. Among those who are younger and who have been working as heads of administration for less than 4 years this percentage is clearly higher (see Fig. 5). 35.2 % of those who have been in office for less than 4 years have previous professional experience in the private sector as opposed to merely 17 % of those who have been head of university administration for more than 9 years.

Following our analysis, the implementation of university reforms based on the model of new public management particularly corresponds to professional specialization and differentiation. Contrary to findings in other countries, and with the exception of recently recruited heads of university administration, there is no clear tendency in Germany toward an increase in recruitment from the private sector. Rather, the main characteristic of administrative university managers is their basic affinity for the academic system.

Organizations and management staff develop expertise in the use of specific instruments of university development and more generic management knowledge in their organizational practices as well as in professional networks and training programs. As in other countries, we can observe an increasing number of specialized courses, study programs, and professional networks that have emerged in Germany over the last years.

Apart from study programs—e.g. at the INCHER at the University of Kassel, the University of Oldenburg, the University of Applied Sciences Osnabrück, the Technical University Berlin, and the German University for Administrative Sciences in Speyer—there are numerous training courses for university and research management, for example, those offered by the Centre for Higher Education (CHE) or the Center for Science and Research Management e.V. Speyer (ZWM). Moreover, in the past years, in addition to traditional associations such as those for heads of university administration, numerous networks in specific fields of university management have emerged, such as the Professional Association for University Communication, the Career Service Network (www.csnd.de), the Association of Alumni Organizations and the Network of Research and Technology Managers (www.forschungsreferenten.de). The main objectives of these networks are the exchange of experiences and knowledge, the development of professional standards, public relations for their common cause and the creation of a commonly shared identity among those who work in areas that to a great extent are rather new to German universities.

The development of specific occupational profiles, patterns of staff recruitment and the establishment of professional networks of university managers indicate that an essentially sector specific expertise is being created, while the orientation toward management concepts from business and the recruitment of management staff from the private sector is of lesser importance. Rather, universities create their own management.

University Managers: Planners with Ambitions to Control or Service Providers for Academics?

In the course of current university reforms some higher education researchers claim that we are witnessing the “colonization of research and teaching by economic and administrative imperatives” (Stock and Wernet 2005: 9). Accordingly, the intensified relationship between academics and administration is critical. Academics fear that the administration has too strong of an effect on the specialized work and independence of academics, as administrative managers are striving to control academic work (Jansen 2007; Pellert 2000: 45). This tension is also discussed in the research literature on the emergence of new managerial professionals in higher education institutions. In an analysis of highly qualified administrative staff, McInnis (1998) showed that in Australian universities tensions between these employees and academics arose when administrative staff members demanded to have an equal footing in the strategic management of the university (ibid.: 168). In a similar vein, Feller (2009) described how the introduction of performance measurement systems at American universities weakened the professional autonomy of departments and faculty, while strengthening the role of administrative managers in academic decision-making processes (ibid.: 339). Furthermore, there is a growing body of comparative empirical research arguing that the introduction of new managerial functions and positions within universities are complemented by a “blurring of boundaries” between administrative and academic work (Whitchurch 2008, 2013; Mcfarlane 2011; Shelley 2010). With the expansion of non-academic tasks and spaces, the roles, skills as well as the identities of university managers become more differentiated (Zellweger-Moser and Bachmann 2010; Gordon and Whitchurch 2010).

But how do administrative university managers see themselves, and how do they understand their role in the organizational framework of the university? Administrative university managers at German universities, like their colleagues in Norway (Gornitzka and Larsen 2004) and in Great Britain (Whitchurch 2008), mainly see themselves as service providers for the different players within the university, the university leadership team and academics in particular. According to our survey data, they mostly describe their professional role as serving as an “adviser to different groups within the university” and as being a “service provider serving and responding to different stakeholders of the university.” Conversely, they do not see themselves so much as agents for implementing decisions taken by the leadership team or as those who ensure formally correct procedures are followed within the university (see Fig. 6).

Self-understanding/description of professional role as administrative manager in %: “To what extent do the descriptions listed below apply to your professional role within in your institution? Professionally I regard myself as …” Please use for your answer a scale from 5 (=fully applies) to 1 (=does not apply at all)

These self-descriptions from our survey were confirmed in the face-to-face interviews we conducted with representatives from this group, especially those directing units for quality management.

“I understand my work as service. Both as far as the leadership team is concerned […] and also as service to the departments. Because, ultimately, the goal is to improve the quality of studying and teaching. Looking at my work this way, I think it is simply a necessary service.” (Head of quality management unit).

“We bring […] the reforms to the departments in a service oriented way. So we are actually saying: ‘Tell us what you need, where can we support you’.” (Head of quality management unit)

Administrative university managers dispose of only limited formal power, as they are dependent on the decisions made by the university leadership team. Thus, the power of the administrative university managers is largely based on sources of power, which do not consist of the decision-making, but in the gathering and distributing of information and expertise as well as subsequent advisory activities. Their main competencies are seen in their expertise with respect to new instruments in particular areas (quality management, controlling, etc.).

“Well, we can make suggestions. The leadership team then decides to what extent it will follow them or not, so, they have full freedom there. We don’t have any leverage there or any authorization to decide. But our expertise is in demand. They say, we are not experts in the area, but you are the experts for this, now please say something about it. Then we can advise, make suggestions. To what extent they accept or implement our suggestions remains their decision, of course.” (Head of quality management unit)

On the other hand, administrative university managers are also dependent on the cooperation of the academics. This is characteristic of a professional organization. Following Mintzberg (1983), universities have to be seen as “professional bureaucracies.” The professionals in the case of the university are the academics, who have a large amount of autonomy, since the core labor processes at universities—research and teaching—are characterized by causal relationships between input and output that are ambiguous and cannot be precisely determined in advance (Musselin 2007: 72; Krücken 2008: 351–353). In addition, like other professionals, university professors have been successful in normatively enforcing their autonomy (Meier and Schimank 2010: 108).

“Of course, I do not have the power to stop the process [authors’ note: a dean intended to send an application to an accreditation agency, which was seen as deficient by the quality management unit]. It is more likely the case that in such a discussion I will say, here, look at this again, we could do it perhaps like this.” (Head of quality management unit)

According to our interview partners, the degree for exercising power is by and large rather low. However, it does vary, especially in the area of quality management. We observed that the closer the relationship between the university leadership team and the quality management unit, and the more communication that takes place between both sides, the more pressure can be exerted on academics. A good example here is the increase of reporting duties academics have to comply with, which go on to serve as a basis for decision-making at the level of the leadership team of the university. However, in most cases exerting pressure is not seen by administrative managers as being appropriate, since according to them the effectiveness of instruments or processes is dependent on the extent to which they are perceived by academics as meaningful.

“I have to do a whole lot of work convincing them and it has to be done right on the spot. It’s the academics […] who I actually want to get on board because in the case of each individual instrument, a course evaluation scheme, for example, […] if they don’t appreciate the instrument, then I don’t have to enforce its use either.” (Head of quality management unit)

The self-perception of a strong service and advisory orientation as well as their rather limited means for exercising power and their alleged reluctance to use power when confronted with resistance can at least partly explain why administrative university managers perceive their work to be largely accepted by the different groups within the university. When asked about their perception of the acceptance of their work by the members of the major status groups, administrative university managers see themselves as very strongly accepted (see Fig. 7). By extension, the interviewees assume that the strongest acceptance is received from the university leadership team.

Both the results from our survey and the quotes from our face-to-face interviews cannot be taken at face value and we cannot tell from our research to what extent the perception of the high acceptance of the work of administrative university managers is equally held by academics and the university leadership team. Furthermore, it could well be that the answers by our respondents are at least partly shaped by the social desirability bias, which comes into play when academics do research on administrative managers. Given the well-known tensions between academics and administrators about issues of control, we cannot exclude that ambitions to control were downplayed by our respondents, while advisory activities and cooperation with academics were overemphasized. Here, we clearly see the necessity of further research that takes into account the perceptions of a broader range of actors, in particular academics, as well as further studies on the dynamics of information and advice as “soft” forms of power in university governance.

Summary and Discussion

The empirical results show that there is, in fact, a growth in administrative university management. This development, which we have analyzed for Germany, is embedded in a transnational trend, concerning very different national systems. Its various underlying causes range from the societal macro-level to changes in university governance and the transformation of the university into an organizational actor. Our results allow for important differentiations that go beyond the current state-of-the-art in research on higher education organizations.

We conclude that the three main research assumptions that guided our journey into the world of administrative higher education management in Germany cannot be confirmed empirically: First, there is no increase in non-academic staff as compared to academic staff. Second, those recruited for administrative university management are primarily from the university sector and only to a much lesser extent from the private sector. Third, the way these people see themselves with regard to their occupational role is supportive and service-oriented, whereas the idea of control that is frequently associated with management is of less significance.

The first part of our analysis showed that an expansion and differentiation of positions in administrative university management has occurred. Both the analysis of job advertisements and the survey of heads of university administration provided evidence of this trend. The major quantitative investigation of staff statistics at German universities, however, surprisingly indicates that this expansion and differentiation has not occurred at the expense of academic staff. Academic staff in the period between 1992 and 2007, both at Ph.D. granting universities and polytechnical schools, has grown, whereas non-academic staff has increased only at polytechnical schools, not at Ph.D. granting universities. This general finding requires further explanation.

First, our results reflect the considerable intensification of third-party funded research at German universities. This is evident not only in the absolute numbers of academics, but also if we disaggregate the numbers of academic staff. Here there is a clear increase, especially at the level of post-doctorate and doctorate staff. According to the statistical data compilation system in Germany, and contrary to those of other countries, the latter are not listed as students, but as academics. We assume that this is one reason why the ratio between academic and non-academic staff in Germany is different from those found in other countries. The number of permanently employed and state-funded academics in German universities decreased compared to overall growth, this in spite of the continuously rising numbers of students and an increase in individual and organizational tasks and missions. This is not without problems; in particular, longer term career prospects below the level of the professoriate have tended to decrease. This gives rise to the question of sustainability, not just of individual careers, but also of research lines. Second, and complementary to this, considerable restructuring can be noted within the non-academic staff. Whereas higher status positions for academics did not increase and the number of professors remained stable over time, there has been a clear rise in higher status positions for non-academic staff, both in absolute as well as relative numbers. The reduction in non-academic staff at universities is based on job reduction and outsourcing in the area of lower qualified jobs. The number of non-academic employees in higher positions, on the other hand, has increased, particularly in the administrative area and with regard to women, who have caught up with men in higher education management at a considerable pace. This also means that our findings, when looked at in more detail, are much closer to those obtained by studies of other countries than they first appear.

Third, the interviews we conducted with people in administrative university management show that the statistical personnel numbers available give an incomplete picture. A large number of those working in these positions, such as, for example, administrative managers of departments, research clusters or graduate schools, are employed as academic staff, even though their area of work clearly belongs to the non-academic field. Here, too, the question arises as to whether, underneath the surface structure, there might be deeper transformations that are made invisible by re-labeling. Fourth, the question arises as to whether the observation of personnel numbers conveys too static of an image of the respective fields of work.

Thus, it could well be the case that academics, over the course of time, increasingly take up non-academic duties that are outside their core activities of research and teaching. The early laboratory study by Latour and Woolgar (1979) describes in great depth how numerous activities involving the economics and politics of research (fundraising, science policy advice and networking, etc.) have to be carried out in order to keep the “research machinery” (as Latour and Woolgar call it) going.Footnote 6 According to them, focusing purely on academic research activities is no longer possible for the senior researchers at the institute they analyzed, even though two of them were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine during Latour and Woolgar’s field research. We assume that in the past years the widening of the job portfolio of academics has increased, and not just for heads of laboratories and institutes in the natural sciences. Even in the social sciences and humanities, and also at the level of young researchers, we believe that the definition of what it means to be an academic has been greatly broadened. “Science as a Vocation” clearly looks different at the beginning of the 21st century as compared to Weber’s (1922) seminal description (see also Shapin 2008). However, long-term time budget studies would be required to verify this assumption.

The second part of our analysis made it clear that recruitment of persons from the private sector is occurring only to a very limited extent in administrative university management in Germany. Even if there are differences among the individual areas of work, the findings still result in a clear overall picture. Compared to work experiences gained in the private sector, those obtained in academic institutions seem to play a more important role. A further indicator of the close proximity to the academic field of those employed in administrative university management can also be seen in the fact that 24 % of those who participated in our survey have a Ph.D. In the same way, the analysis of the disciplinary backgrounds of those surveyed revealed surprising findings, at least if we assume that the prerequisite for heads of units in administrative university management is a background in business administration, economics or law. Instead, most of them have a humanities background, then, at a distant second, we find those from business administration and economics, followed closely by social scientists, whereas lawyers hardly play any role and even rank behind natural scientists and engineers. We can only speculate on the reasons for this profile, as well as on the low recruitment from the private sector. On the one hand, context-specific knowledge and soft skills seem to be of major importance for the job. On the other hand, also the existence or non-existence of attractive job markets outside the university sector and the rather lower salary compared to the private sector seems to play an important role.

In the second part of the analysis we also dealt with the disciplinary backgrounds of the heads of university administration (“Kanzler”). Here we see important transformations. Whereas the older heads almost exclusively have a law degree and professional experiences in the university sector, the picture for the younger ones is much more heterogeneous. Compared to their older colleagues, professional experiences in the private sector are more frequent and the almost exclusively legal background is replaced by a plurality of disciplinary backgrounds. This opening up was enabled by legal changes in almost all state university laws since the 1990s. Whereas previously a law degree was a formal requirement for being appointed as head of administration in a public university, in most German federal states such a requirement no longer exists. This change, which particularly favors graduates in business administration and economics, is embedded in the transformation of universities into an integrated, goal-oriented, and competitive entity in which management and leadership play an ever more important role. In such a context, more and more opportunities for decision-making are created, which requires not only legal expertise. It is noticeable that both within the individual areas of administrative university management (international affairs, executive & continuing education, career service, quality management, technology transfer, and marketing & public relations) and at the level of the heads of university administration, numerous activities take place that go beyond the organizational level.

However, in spite of several programs that in some cases even lead to an academic degree in higher education management, we find little evidence for the formation of a general occupational group of higher education managers. The tendencies toward professionalization that we noticed were instead linked to area or status specific networks, not to the field as such. Management as a profession with transferable skills and generic competencies can rarely be observed in the higher education sector.Footnote 7

In the third part of the analysis we were concerned with the way in which administrative university managers at German universities perceive themselves. This part was based on a standardized survey and in-depth interviews and we are aware of the limits of oral representations by only one group of actors. However, even given these limitations, it became clear that the heads of units in different areas of the university primarily see themselves in an advisory role and as service providers for both the university leadership team and academics. Aspirations to exert direct control, on the other hand, could hardly be detected. Yet, influence can be exercised within the university through the medium of information and possibilities for agenda setting. Though the effects of such “soft” forms of power should not be underestimated and deserve further research, information and agenda-setting remain indirect methods and are dependent on cooperation. The foundation for directly enforcing collectively binding decisions, which in many sociological analyses of power is seen as essential (Luhmann 1979), does not exist. The limited bases of decision-making by administrative higher education managers shed some doubts on the aforementioned success story of women in this area. Identity constructs in which the supportive role is stressed mirror the actual powerlessness of many higher education managers vis-à-vis academics in Germany. Therefore, the strong increase of women in higher grade administrative positions does not necessarily imply a shifting balance of power between men and women in academia.

Whereas in the introduction of our paper we mainly pointed out the parallels between the inception of industrial management and that of university management, here at the end and based on our analysis of the managerial turn in German academia we would rather stress the differences between the two sectors. These differences refer to the possibilities and limits of exercising influence by those managers who are not part of the top management of the organization.Footnote 8 The early work of Taylor (1911) already showed that for industrial companies the middle management had a central position between the company management and other employees. This type of “sandwich position” is also acquired by administrative university managers, since they are typically positioned between the university leadership team and the departments, where most of the academic work is carried out. Furthermore, they frequently have to perform intermediary and translation work in both directions.

The central and intermediary position of middle managers has also been pointed out by Chandler (1977: 3–7, 381–414). According to him, middle managers substituted for market mechanisms in the monitoring and coordination of the production and distribution units in industrial firms. The analogy to both the internal structures of universities that consist of loosely coupled departments and the work descriptions of the middle managers we interviewed is evident. However, the position of administrative middle managers in universities is clearly weaker than in industrial organizations. Their status vis-à-vis university professors is rather low and core labor processes in universities—research and teaching—are highly complex and rife with uncertainty. As a result, these processes cannot really be controlled by the visible hand of administrative middle management in universities in the way comparably simple labor processes of industrial mass production and distribution are controlled.

Finally, the university as an organization is of only minor importance to many academics as compared to their scientific community. It is among networks of peers, not within a formal organization, where competition for the scarce resource that matters most to academics—scientific reputation—takes place. As a consequence, we assume that the effects of the current managerial turn in higher education are buffered by the core characteristics of a professional organization that have been retained—at least in the German case. Here, the changes brought about by the visible hand of administrative middle management in universities seem to turn out to be less far-reaching than those that Chandler (1977) observed in the early phase of industrial management. Based on these results, an interesting research agenda unfolds, in which different national and organizational characteristics and trajectories have to be compared with regard to the impact of the general managerial turn in higher education.

Notes

According to official statistics, at German universities there are 8,110 persons employed in university administration and management that belong to the status group of “higher grade” of which only some occupy a leadership-position (Statistisches Bundesamt 2009: 10).

The head of university administration, similar to the position of a vice-president for finance and human resources, administrative director or provost in Anglo-American higher education systems but in Germany traditionally referred to as “Kanzler,” are not easily located within this categorisation. Like the president/rector and the vice-presidents, they are part of the university leadership team and according to most state laws, the academic senate is involved in their appointment. Therefore, they belong to the first group. However, as senior civil servants they are full-time administrators and not academics and therefore also belong to the second group.

Contrary to appropriations in other contributions in higher education research using the terms “non-academic staff” and “administrative staff” synonymously, in the German context non-academic staff cannot be equated with administrative staff. Based on the attribution of different work areas according to statistical reports, non-academic staff at German universities differentiate between the following categories of non-academic staff: administrative staff, technical staff, library staff and other staff (Statistisches Bundesamt 2009, Erläuterungen).

For further results and discussions concerning gender issues in German higher education management, see Krücken et al. (2012).

Systematic studies on academic backgrounds and career paths of higher administrators at German universities have not been conducted so far. However, there are general surveys on administrative elites in Germany (Derlien and Mayntz 1988; Derlien 2003; Bogumil et al. 2012). These studies show that members of these elites most typically have a law degree and pursued a distinct career path within the realm of public administration.

For similar results with regard to public research organizations in Italy, see also Coccia (2009).

In this, we find another interesting parallel to the inception of management in the business sector. According to Chandler (1977), during the managerial revolution managers had field-specific expertise, as they were experts on specific sectors of mass production or distribution. A railroad manager could hardly transfer his skills to the retail sector. Over the 20th century, however, the sharp boundaries between sectors became blurred and management was increasingly seen as a generic competence that could be learned and trained and that diffuses widely across countries and sectors (Sahlin-Andersson and Engwall 2002). It is an open and highly interesting question whether we will observe a similar trend in the higher education sector.

In addition, see the account by Hüther and Krücken (2011) of the differences with regard to the top management level. According to the analysis presented, university leadership in Germany is comparably weak due to various aspects that mainly relate to the high degree of autonomy of the professoriate. Nevertheless, we assume that the top management at German universities, which is by and large composed of university professors, can bring about more profound changes than the administrative middle managers we analyzed in this paper. Likewise, further analyses should also include the changing role of deans in the management of higher education.

References

Amaral, Alberto, V. Lynn Meek, and Ingvild Marheim Larsen (eds.). 2003. The higher education managerial revolution? Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Basnett, Susan. 2005. The importance of professional university administration: A perspective from a senior university manager. Perspectives 9: 98–102.

Bogumil, Jörg, Falk Ebinger, and Linda Jochheim. 2012. Spitzenbeamte und ihr Verhalten bei politisch relevanten Entscheidungen. In Bürokratie im Irrgarten der Politik. Schriften der Deutschen Sektion des Internationalen Instituts für Verwaltungswissenschaften Bd. 36, eds. Dieter Schimanke, Sylvia Veit, and Hans Peter Bull, 151–174. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

Chandler, Alfred D. 1977. The visible hand. The managerial revolution in American business. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Coccia, Mario. 2009. Bureaucratization in Public Research Institutions. Minerva 47: 31–50.

de Boer, Harry, Jürgen Enders, and Liudvika Leisyte. 2007. On striking the right notes. Shifts in governance and the organizational transformation of universities. Public Administration 85: 27–46.

Deem, Rosemary, Sam Hillyard, and Mike Reed. 2007. Knowledge, higher education policy and management of UK universities. Oxford: Open University Press.

Derlien, Hans-Ulrich, and Renate Mayntz. 1988. Comparative elite study II: Einstellungen der politisch-administrativen Elite des Bundes 1987. Bamberg: Universität Bamberg.

Derlien, Hans-Ulrich. 2003. Mandarins or managers? The bureaucratic elite in Bonn, 1970–1987 and beyond. Governance 16: 401–428.

Feller, Irwin. 2009. Performance measurement and the governance of American academic science. Minerva 47(3): 323–344.

Fligstein, Neil. 1990. The transformation of corporate control. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Frank, David J., and Jay Gabler. 2006. Reconstructing the university. Worldwide shifts in academia in the twentieth century. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

Goldwater Institute. 2010. Administrative bloat at American universities. The real reasons for high costs in higher education. Policy report no. 239. Phoenix.

Gordon, George, and Celia Whitchurch (eds.). 2010. Academic and professional identities in higher education: The challenges of a diversifying workforce. International studies in higher education. New York: Routledge.

Gornitzka, Ase, and Ingvild Larsen. 2004. Towards professionalism? Restructuring of administrative work force in universities. Higher Education 47: 455–471.

Harman, Grant, and Christopher Stone. 2006. Australian university technology transfer managers: Backgrounds, work roles, specialist skills and perceptions. Journal of Higher Education Policy & Management 28: 213–230.

Hüther, Otto. 2010. Von der Kollegialität zur Hierarchie? Eine Analyse des New Managerialism in den Landeshochschulgesetzen. Wiebaden: Gabler.

Hüther, Otto, and Georg Krücken. 2011. Wissenschaftliche Karriere und Beschäftigungsbedingungen—organisationssoziologische Überlegungen zu den Grenzen neuer Steuerungsmodelle an deutschen Hochschulen. Soziale Welt 62: 303–323.

Jansen, Dorothea. 2007. Governance—An integrated theory. In New forms of governance in research organizations—Disciplinary approaches, interfaces and integration, ed. Dorothea Jansen, 104–126. Dordrecht: Springer.

Kickert, Walter J.M. (ed.). 1997. Public management and administrative reform in Western Europe. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Klumpp, Matthias, and Ulrich Teichler. 2006. Experten für das Hochschulsystem. Hochschulprofessionen zwischen Wissenschaft und Administration. In Hochschulprofessionen—zwischen Wissenschaft und Administration, eds. Barbara M. Kehm, Evelies Mayer, and Ulrich Teichler, 2–3. hi hochschule innovativ 16—Darmstadt-Kassel-Runde Series. Bonn: Lemmens.

Kocka, Jürgen. 1969. Industrielles Management: Konzeptionen und Modelle in Deutschland vor 1914. Vierteljahresschrift für Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte 56: 332–372.

Krücken, Georg. 2008. Lässt sich Wissenschaft managen? Wissenschaftsrecht 41: 345–358.

Krücken, Georg. 2011. A European perspective on new modes of university governance and actorhood. Research & occasional paper series: CSHE. 17.11. Berkeley: University of California.

Krücken, Georg, Katharina Kloke, and Albrecht Blümel. 2012. Alternative Wege an die Spitze? Karrierechancen von Frauen im administrativen Hochschulmanagement. In Einfach Spitze? Frauen in der Spitzenforschung, eds. Sandra Beaufaÿs, Anita Engels, and Heike Kahlert, 119–141. Frankfurt a.M./New York: Campus.

Krücken, Georg, and Frank Meier. 2006. Turning the University into an Organizational Actor. In Globalization and organization. World society and organizational change, eds. Gili S. Drori, Hokyu Hwang, and John Meyer, 241–257. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lange, Stefan, and Georg Krücken. 2011. German Universities in the New Knowledge Economy. Current Changes in Research Conditions and University-Industry Relations. In Knowledge Matters. The Transformation of ‚Public’ Research Universities, eds. Diana Rhoten, and Craig Calhoun, 342–376. New York: Columbia University Press.

Latour, Bruno, and Steve Woolgar. 1979. Laboratory life. The social construction of scientific facts. Sage: Beverly Hills et al.

Leicht, Kevin T., and Mary L. Fennell. 2008. Who staffs the US leaning tower? Organisational change and diversity. Equal Opportunities International 27: 88–106.

Leichsenring, Hannah. 2007. Die Professionalisierung des Fakultätsmanagements. Bericht zur Befragung 2006, Arbeitspapier Nr. 87. Gütersloh: CHE.

Logue, Danielle. 2010. The diffusion of management innovations: Understanding 90 years of global organisational change in universities. Completed dissertation. Oxford: Said Business School, University of Oxford.

Luhmann, Niklas. 1979. Trust and power. Chichester: Wiley.

Mcfarlane, Bruce. 2011. The morphing of academic practice: Unbundling and the rise of the para-academic. Higher Education Quarterly 65(1): 59–73.

McInnis, Craig. 1998. Academics and professional administrators in Australian universities: Dissolving boundaries and new tensions. Journal of Higher Education Policy & Management 20: 61–73.

Meier, Frank, and Uwe Schimank. 2010. Organisationsforschung. In Handbuch Wissenschaftspolitik, eds. Dagmar Simon, Andreas Knie, and Stefan Hornbostel, 106–117. Wiesbaden: VS-Verlag.

Middlehurst, Robin. 2004. Changing internal governance: A discussion of leadership roles and management structures in UK universities. Higher Education Quarterly 58: 258–279.

Mintzberg, Henry. 1983. Structure in fives. Designing effective organizations. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Musselin, Christine. 2007. Are Universities Specific organisations? In Towards a multiversity? Universities between global trends and national traditions, eds. Georg Krücken, Anna Kosmützky, and Marc Torka, 63–84. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.

Paradeise, Catherine, Emanuela Reale, Ivar Bleiklie, and Ewan Ferlie (eds.). 2009. University governance. Western European comparative perspectives. Higher Education Dynamics Series, Vol. 25. Dordrecht: Springer.

Pausits, Attila, and Ada Pellert. 2009. Winds of change: Higher education management programmes in Europe. Higher Education 34: 39–49.

Pellert, Ada. 2000. Expertenorganisationen reformieren. In Hochschulen managen? Zur Reformierbarkeit der Hochschulen nach Managementprinzipien, ed. Anke Hanft, 39–55. Neuwied: Luchterhand.

Pollitt, Christopher, and Geert Bouckaert. 2000. Public management reform. A comparative analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rhoades, Gary. 1998. Managed professionals: Unionized faculty and restructuring academic labor. Albany: State University Press.

Rhoades, Gary, and Barbara Sporn. 2002. New models of management and cost production: Europe and the United States. Tertiary Education and Management 8: 3–28.

Sahlin-Andersson, Kerstin, and Lars Engwall (eds.). 2002. The expansion of management knowledge. Carriers, flows, and sources. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

Schimank, Uwe. 2005. “New Public Management” and the academic profession. Reflections on the German situation. Minerva 43: 361–376.

Schimank, Uwe, and Stefan Lange. 2009. Germany: A latecomer to new public management. In University governance—Western European comparative perspectives, eds. Catherine Paradiese, Emanuela Reale, Ivar Bleiklie, and Ewan Ferlie, 51–75. Dordrecht: Springer.

Schofer, Evan, and John Meyer. 2005. The world-wide expansion of higher education in the twentieth century. American Sociological Review 70: 898–920.

Shapin, Steven. 2008. The scientific life. A moral history of a late modern vocation. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Shelley, Louise. 2010. Research managers uncovered: Changing roles and ‘Shifting Arenas’ in the academy. Higher Education Quarterly 64(1): 41–64.

Smith, David, and Jonathan Adams. 2008. Academics or executives? Continuity and change in the roles of pro-vice-chancellors. Higher Education Quarterly 62: 340–357.

Statistisches Bundesamt. 2009. Personal an Hochschulen. Fachserie 11 Reihe 4.4. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Publikationen/Thematisch/BildungForschungKultur/AlteAusgaben/PersonalHochschulenAlt.html . Accessed 17 May 2013.

Stock, Manfred, and Andreas Wernet. 2005. Hochschulforschung und Theorie der Professionen. Die Hochschule 2:7–14.

Szekeres, Judy. 2004. The invisible workers. Journal of Higher Education Policy & Management 26: 7–22.

Taylor, Frederick W. 1911. The principles of scientific management. London: Harper & Brothers.

Teichler, Ulrich, and Ester Ava Höhle (eds.). 2013. The work situation of the academic profession in Europe: Findings of a survey in twelve countries. Dordrecht: Springer.

Visakorpi, Jarmo. 1996. Academic and administrative interface: Application to national circumstances. Higher Education Management 8: 37–40.

Weber, Max. 1922. Wissenschaft als Beruf. In Gesammelte Aufsätze zur Wissenschaftslehre, ed. Max Weber, 524–555. Tübingen: Mohr (English translation: Science as a Vocation. In From Max Weber: Essays in sociology, eds. Hans Heinrich Gerth, and C. Wright Mills, 129–156. New York: Oxford University Press, 1946).

Whitchurch, Celia. 2008. Shifting identities and blurring boundaries: The emergence of third space professionals in UK higher education. Higher Education Quarterly 62: 377–396.

Whitchurch, Celia. 2004. Administrative managers—A critical link. Higher Education Quarterly 58: 280–298.

Whitchurch, Celia. 2013. Reconstructing identities in higher education: The rise of third space professionals. London: Routledge.

Zellweger-Moser, Franziska, and Gudrun Bachmann. 2010. Zwischen Administration und Akademie—Neue Rollen in der Hochschullehre. Zeitschrift für Hochschulentwicklung 5: 1–8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Krücken, G., Blümel, A. & Kloke, K. The Managerial Turn in Higher Education? On the Interplay of Organizational and Occupational Change in German Academia. Minerva 51, 417–442 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11024-013-9240-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11024-013-9240-z