Abstract

The relationship between hepatic encephalopathy (HE) and the sleep-wake disturbances exhibited by patients with cirrhosis remains debated. The aim of this study was to examine the usefulness of sleep-wake interview within the context of HE assessment. One-hundred-and-six cirrhotic patients were asked three yes/no questions investigating the presence of difficulty falling asleep, night awakenings and daytime sleepiness. All underwent formal HE assessment, quantitative electroencephalography and standardised psychometry. Fifty-eight were monitored for 8 ± 6 months in relation to the occurrence of HE. Patients complaining of daytime sleepiness (n = 75, 71 %) had slower EEGs than those who did not report it (relative alpha power: 37 ± 19 vs. 48 ± 17 %, p < 0.05). In addition, daytime sleepiness was associated with the presence of portal-systemic shunt (79 vs. 57 %, p < 0.05) and HE history (72 vs. 45 %, p < 0.05). Finally, the absence of excessive daytime sleepiness had a Negative Predictive Value of 92 % (64–100) in relation to the development of HE during the follow-up period. These data support the appropriateness of adding a yes/no question on the presence of excessive daytime sleepiness to routine assessment of patients with cirrhosis, to help identify those who do not need further, formal HE screening.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The relationship between hepatic encephalopathy (HE) and the sleep-wake disturbances exhibited by patients with cirrhosis remains debated (Sherlock et al. 1954; Cordoba et al. 1998; Mostacci et al. 2008; Montagnese et al. 2009b; Bianchi et al. 2005; Bersagliere et al. 2012). The aim of this study was to assess the value of a set of three yes/no questions on sleep-wake patterns within the context of HE screening/evaluation procedures.

Materials and methods

One hundred and six consecutive outpatients with cirrhosis and no/grade I HE according to the West Haven criteria (Conn et al. 1977) were enrolled [77 men, age: 57 ± 11 (mean ± SD) yrs; Child class A:36 (34 %); B:49 (46 %), C:21 (20 %); Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD): 13 ± 5]. Patients were excluded if the aetiology of cirrhosis was non-alcoholic steato-hepatitis, if they were overweight/obese, had diagnosed/suspected obstructive sleep-apnoea syndrome, cerebrovascular/cardiovascular disease, renal failure, significant neurological or psychiatric co-morbidity, were taking psychoactive drugs or drugs known to affect sleep/circadian rhythmicity.

HE assessment

Psychometric performance was assessed using the paper-and-pencil Psychometric Hepatic Encephalopathy Score (PHES) (Weissenborn et al. 2001) and individual test results scored in relation to age- and education-adjusted Italian norms (Amodio et al. 2008). Eyes-closed, wake electroencephalograms (EEG) were recorded and analysed spectrally, as previously described (Amodio et al. 1999).

Portal-systemic shunts

Echo-Doppler evaluations were obtained in 69 patients (65 %) by three equally experienced operators (BG, BM, SD), using one ultrasound machine (ATL 5000, Philips) with a 5 MHz convex probe provided by a colour- and pulsed-Doppler device. Patients were qualified as having portal-systemic shunts if convoluted, anechoic channels were detected, and venous flow confirmed by colour-Doppler (Berzigotti et al. 2008).

Sleep-wake patterns

Patients were also asked to answer yes/no to three questions, investigating the presence, in their everyday life, of: i) difficulty falling asleep; ii) frequent night awakenings; iii) excessive daytime sleepiness. Two validated questionnaires assessing night sleep quality [Sleep Timing and Sleep Quality Screening (STSQS) questionnaire (Montagnese et al. 2009c) and daytime sleepiness [Epworth Sleepiness Scale (Johns 1991)] were used as reference.

HE history and HE development

Information was obtained on previous episodes of overt HE (clinical records plus patients’/relatives’ reports). Finally, 58 patients (55 %) patients were followed prospectively for 8 ± 6 months, in relation to the occurrence of death/transplantation and HE-related hospitalisations.

Statistical analysis

Differences between groups were examined by the Student t or Mann–Whitney U tests, as appropriate. Categorised indices were compared by the Pearson’s χ2. Survival/HE-free survival analysis was performed by the Kaplan-Meier cumulative survival method. Since all transplanted patients had been transplanted for liver failure (as opposed to liver cancer), they were qualified as ‘dead’ on the day of transplantation; the analysis was also repeated having excluded transplanted patients. The Positive/Negative Predictive Value (P/NPV) of sleep-wake disturbances in relation to the development of HE-related hospitalisations was also calculated.

Results

Thirty-eight (36 %) of the patients complained of difficulty falling asleep, 53 (51 %) of frequent night awakenings and 75 (71 %) of excessive daytime sleepiness. Patients complaining of night sleep disturbance (difficulty falling asleep and/or frequent night awakenings) had significantly higher STSQS scores than those who did not (6.4 ± 1.9 vs. 2.9 ± 1.3, p < 0.0001). Similarly, patients complaining of excessive daytime sleepiness had significantly higher Epworth Sleepiness Scale scores than those who did not (7.3 ± 4.2 vs. 3.8 ± 2.3, p < 0.01). No association was observed between the presence of night sleep disturbances (difficulty falling asleep and/or frequent night awakenings) and that of excessive daytime sleepiness (χ2 = 3.6, p > 0.05).

No association was observed between the presence of sleep-wake disturbances and the degree of hepatic impairment/the presence of overt HE on the day of study. Similarly, no consistent relationships were observed between the presence of difficulty falling asleep/frequent night awakenings and quantitative indices of HE (Table 1). In contrast, patients who complained of excessive daytime sleepiness had significantly slower EEG than their counterparts with no difficulties staying awake (Table 1).

No association was observed between difficulty falling asleep/frequent night awakenings and a history of HE and/or the presence of portal-systemic shunt. In contrast, excessive daytime sleepiness was associated with both a history of HE and the presence of portal-systemic shunt (Table 1).

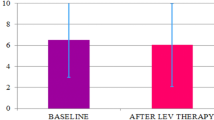

During the follow-up period, 4 (7 %) patients died, 9 (16 %) underwent OLTx and 14 (24 %) had HE-related hospitalisations. No association was observed between sleep-wake abnormalities and survival or between difficulty falling asleep/frequent night awakenings and the development of HE over time. In contrast, excessive daytime sleepiness at baseline was associated with an increased risk of HE-related hospitalisation (Figure 1). Excessive daytime sleepiness had a PPV of 33 % [Confidence Interval (CI): 19–49] and a NPV of 92 % (CI: 64–100) in relation to the development of HE during the follow-up period.

Discussion

Sleep-wake disturbances, as assessed by a simple, structured interview were found to be common in patients with cirrhosis. This is in line with previous studies based on similar structured interviews (Cordoba et al. 1998; Bianchi et al. 2005), validated questionnaires (Mostacci et al. 2008; Montagnese et al. 2009b) and semi-quantitative assessment tools, such as actigraphy (Cordoba et al. 1998; Montagnese et al. 2009a).

Of interest, while no association was observed between difficulties falling asleep/frequent night awakenings and HE, excessive daytime sleepiness was associated with quantitative HE indices (EEG slowing), a history of HE and its development over time. In addition, excessive daytime sleepiness was also associated with the presence of portal-systemic shunt, which is known to be implicated in the pathophysiology of HE (Riggio et al. 2005). These findings have both mechanistic and practical implications in that: i) they lend support to the interpretation of HE as a vigilance defect (Ross 1991; Montagnese et al. 2007; Montagnese et al. 2009b); ii) they suggest that a simple yes/no question investigating the presence of excessive daytime sleepiness may help identifying patients who are/are not at risk of HE. Given the high NPV of the test, its main practical use may lay in the identification of patients who do not need further, formal HE assessment.

In conclusion, our data support the appropriateness of adding a yes/no question on the presence of excessive daytime sleepiness to the routine assessment of patients with cirrhosis. Studies evaluating the cost-effectiveness of subsequent, saved formal HE evaluations may be worthy.

Abbreviations

- HE:

-

Hepatic Encephalopathy

- MELD:

-

Model for End-stage Liver Disease

- PHES:

-

Psychometric Hepatic Encephalopathy Score

- EEG:

-

Electroencephalogram

- P/NPV:

-

Positive/Negative Predictive Value

- STSQS:

-

Sleep Timing and Sleep Quality Screening

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

References

Amodio P, Campagna F, Olianas S, Iannizzi P, Mapelli D, Penzo M et al (2008) Detection of minimal hepatic encephalopathy: normalization and optimization of the Psychometric Hepatic Encephalopathy Score. A neuropsychological and quantified EEG study. J Hepatol 49:346–353

Amodio P, Marchetti P, Del Piccolo F, De Toni M, Varghese P, Zuliani C et al (1999) Spectral versus visual EEG analysis in mild hepatic encephalopathy. Clin Neurophysiol 110:1334–1344

Bersagliere A, Raduazzo ID, Nardi M, Schiff S, Gatta A, Amodio P et al (2012) Induced hyperammonemia may compromise the ability to generate restful sleep in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 55:869–878

Berzigotti A, Merkel C, Magalotti D, Tiani C, Gaiani S, Sacerdoti D et al (2008) New abdominal collaterals at ultrasound: a clue of progression of portal hypertension. Dig Liver Dis 40:62–67

Bianchi G, Marchesini G, Nicolino F, Graziani R, Sgarbi D, Loguercio C et al (2005) Psychological status and depression in patients with liver cirrhosis. Dig Liver Dis 37:593–600

Conn HO, Leevy CM, Vlahcevic ZR, Rodgers JB, Maddrey WC, Seeff L et al (1977) Comparison of lactulose and neomycin in the treatment of chronic portal-systemic encephalopathy. A double blind controlled trial. Gastroenterology 72:573–583

Cordoba J, Cabrera J, Lataif L, Penev P, Zee P, Blei AT (1998) High prevalence of sleep disturbance in cirrhosis. Hepatology 27:339–345

Johns MW (1991) A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep 14:540–545

Montagnese S, Jackson C, Morgan MY (2007) Spatio-temporal decomposition of the electroencephalogram in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol 46:447–458

Montagnese S, Middleton B, Mani AR, Skene DJ, Morgan MY (2009a) Sleep and circadian abnormalities in patients with cirrhosis: features of delayed sleep phase syndrome? Metab Brain Dis 24:427–439

Montagnese S, Middleton B, Skene DJ, Morgan MY (2009b) Night-time sleep disturbance does not correlate with neuropsychiatric impairment in patients with cirrhosis. Liver Int 29:1372–1382

Montagnese S, Middleton B, Skene DJ, Morgan MY (2009c) Sleep-wake patterns in patients with cirrhosis: all you need to know on a single sheet. A simple sleep questionnaire for clinical use. J Hepatol 51:690–695

Mostacci B, Ferlisi M, Baldi AA, Sama C, Morelli C, Mondini S et al (2008) Sleep disturbance and daytime sleepiness in patients with cirrhosis: a case control study. Neurol Sci 29:237–240

Riggio O, Efrati C, Catalano C, Pediconi F, Mecarelli O, Accornero N et al (2005) High prevalence of spontaneous portal-systemic shunts in persistent hepatic encephalopathy: a case–control study. Hepatology 42:1158–65

Ross CA (1991) CNS arousal systems: possible role in delirium. Int Psychogeriatr 3:353–371

Sherlock S, Summerskill WH, White LP, Phear EA (1954) Portal-systemic encephalopathy; neurological complications of liver disease. Lancet 267:454–457

Weissenborn K, Ennen JC, Schomerus H, Ruckert N, Hecker H (2001) Neuropsychological characterization of hepatic encephalopathy. J Hepatol 34:768–773

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

De Rui, M., Schiff, S., Aprile, D. et al. Excessive daytime sleepiness and hepatic encephalopathy: it is worth asking. Metab Brain Dis 28, 245–248 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11011-012-9360-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11011-012-9360-4