Abstract

Increasingly, manufacturers sell their products in their own retail stores, and many of these stores appear to be in direct competition with independent retailers; i.e., both types of retail stores are physically co-located. We analyze one way this practice affects the retail market. We find that, when independent retailers compete against company stores (instead of just against other independent retailers), they (1) charge higher prices and (2) are more willing to engage in marketing efforts on behalf of the manufacturer’s brand. Furthermore, when company stores and independent retailers compete in the same market, the company store charges higher prices and provides more marketing effort. Anecdotal data are consistent with these model predictions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Traditional roles for manufacturers and retailers are blurring, and their activities are becoming more intertwined. One prominent and largely unstudied phenomenon that exemplifies this trend is “partial forward integration” (PFI) by manufacturers. In general, PFI describes a setting where the manufacturer sells to end consumers not only through traditional independent retailers but also through company-owned stores. A shopper strolling down the major boulevards in cities around the world might encounter stores owned by Apple, Bally, Nike, Ralph Lauren, and more recently, even automobile manufacturers such as Audi, to name just a few. Similarly, shopping malls in the USA routinely have a substantial number of manufacturer-owned retail stores.

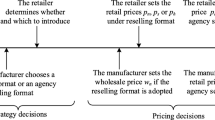

We focus on a specific type of PFI: The manufacturer-owned stores and independent retailers co-exist in the same physical location and therefore potentially serve the same customer base.Footnote 1 In this paper, we term this arrangement the company store (CS) channel. Our goal is straightforward: to understand how the CS channel affects outcomes in the retail market, in particular, prices charged and levels of marketing effort placed behind the manufacturer’s brand. We use a standard modeling approach (e.g., Lal 1990; McGuire and Staelin 1983) to derive retail market outcomes under two regimes:

-

1.

Independent structure (I). Manufacturing and selling are delineated. The manufacturer produces the good and contracts with retailers who sell it to consumers.

-

2.

Company store structure (CS). Independent retailers still sell the product, but in addition, the manufacturer supports a physically co-located retail store.

As noted earlier, real-world examples of CS channels are numerous. Goodyear serves consumers in the Mid-Peninsula region of the Bay Area through its Goodyear Tire Center as well as Palo Alto Tire & Brake, and Redwood General Tire Service. Armani, DKNY, Dr. Martens, Hugo Boss, Kenneth Cole, and Polo Ralph Lauren operate company stores in locations where independent retailers (e.g., Macy’s and Nordstrom) also carry their products. CS channels are of interest for at least two reasons. First, they appear to involve duplication of effort, which raises a question concerning their function. Second, they could give rise to “price squeezing” by the manufacturer (price squeezing occurs when additional margins obtained from wholesale price increases to independent retailers are diverted to retail marketing activities at the company store). Not surprisingly, battles over price squeezing have been fought in the courts.Footnote 2 Similarly, resale price maintenance—i.e., efforts by the manufacturer to elicit retail prices that are higher than those that would be optimally set by retailers acting independently—was illegal up until 2007 and is still under challenge.Footnote 3

By analyzing an increasingly prevalent but largely unstudied channel structure, we offer two new contributions to the channels literature. First, we show that neither price squeezing nor explicit resale price maintenance need occur in the CS channel. Rather, when consumer demand is affected by own and competitor marketing efforts at the retail level, it is possible to find “complementary benefits” for both parties. Specifically, the presence of a company store provides an incentive for independent retailers to charge more and to invest more in non-price marketing activity than when the company store is absent from the retail market. That is, by opening a company store in close proximity to an independent retailer who carries his products, the manufacturer can induce the retailer to charge more and provide more retail marketing effort than when the retailer faces another independent retailer only. Second, when company stores and independent retailers compete, the former charges more and puts in more marketing effort, thus setting the overall marketing “standard” for the retail market.

Some caveats are worth mentioning. In this short paper, we do not attempt an exhaustive theory of PFI; rather, we focus exclusively on the CS channel and one set of market effects. The setup therefore deliberately ignores alternative manufacturer motivations for the CS channel including, for example, information acquisition, market testing, retailer benchmarking, and so forth. The basic findings are, however, robust to some additional market complexities and consistent with anecdotal data.Footnote 4

The paper is organized as follows. The next section motivates the research. The subsequent section develops the basic model, describes the key findings, and presents some extensions. The concluding section presents anecdotal data, discusses the results, and suggests implications for practice and future research.

1 Background and related literature

We briefly describe key findings from the relevant extant literature. We focus exclusively on analytical approaches to studying the effect of channel structure and channel alignment on retail market outcomes.

Channel structure and retail market outcomes

Several studies (e.g., Coughlan 1985; McGuire and Staelin 1983; Moorthy 1987; Trivedi 1998) consider how retail prices differ when manufacturers go direct to market or use independent retailers. While the use of independents naturally leads to double marginalization, the manufacturer decision to forward-integrate depends on product substitutability. Highly substitutable products tend to be sold through independent retailers in a decentralized system (McGuire and Staelin 1983). Manufacturers may also use intermediaries to mitigate direct price competition at the manufacturer level (Coughlan 1985). Trivedi (1998) introduces “store substitutability” and obtains the McGuire and Staelin (1983) results as a special case of her model. In summary, the majority of published articles (1) compare channels that are “symmetric” integrated and independent channels, and (2) focus on price as the key marketing variable. This is also true for studies that examine multiple products (e.g., Choi 1991). Our research considers non-price variables and analyzes an explicitly asymmetric PFI channel structure.Footnote 5

Channel alignment and retail market outcomes

When manufacturers and retailers are independent entities, conflict and “local optimization” of marketing decisions can occur (e.g., Eliashberg and Mitchie 1984). Even when “marketing effort” can positively affect demand, independent retailers might focus on the “wrong” margins (from the manufacturer’s point of view) and engage in excessive retail price competition (Winter 1993).Footnote 6 Lal (1990) studies this phenomenon in a franchising context. He shows that franchisees can free-ride on each other with respect to the provision of service in the retail market. Imagine that two franchised McDonald’s restaurants have some market overlap. If only one franchisee invests in local television advertising, both can still benefit from an increase in demand. If each franchisee knows this, and if advertising is costly, neither may invest in advertising. If the threat of free-riding undermines brand-enhancing activities by retailers in this way, the manufacturer can be hurt as well.

The franchisor (manufacturer) can achieve compliance in many ways including monitoring systems (e.g., “surprise visits” to outlets) and contractual arrangements that bind each party to minimal brand-building efforts. We do not address these mechanisms but instead study how the CS arrangement affects retail market outcomes of interest to manufacturers. In this sense, our paper is conceptually related to but different from prior work on channel structure and member alignment. In the next section, we show how direct involvement in the retail market by the manufacturer can limit the “negative” effect of non-price competition between independent retailers.

2 Model and findings

We analyze the independent (I) and company store (CS) channels using a standard setup. To demonstrate that the qualitative results are preserved in more general settings, we subsequently consider additional market features. These include differing levels of retailing efficiency at independent retailers and company stores, price competition, shopper heterogeneity in brand loyalty, and inter-brand competition.

2.1 Model assumptions

The manufacturer produces a single brand; sets the wholesale price, w, and has zero marginal cost (for ease of exposition). We employ a variant of the standard setup (e.g., Bhardwaj 2001; Chu and Desai 1995; Lal 1990; McGuire and Staelin 1983; Raju et al. 1995; Trivedi 1998) where competing independent retailers decide on a retail price, p, and the level of marketing effort, e, and there are no additional terms of trade.Footnote 7 Consistent with the extant literature, “marketing effort” captures all elements of value added to the brand at the retail level (e.g., salesperson effort, retailer advertising, in-store displays, etc.). The purchase of a Ralph Lauren suit, for example, may depend upon the salesperson’s ability to explain product quality and features to the shopper. As in Lal (1990), marketing effort not only benefits the investing retailer but also other competing retailer(s) located in close physical proximity (retailer j makes the sale, even though a salesperson at retailer i first informed the customer and influenced the purchase decision). For a market with n = 2 retailers, the demand at retailer s is

where s = 1, 2 and β is an “effort spillover” parameter that captures how much shoppers remember stimuli associated with marketing effort from the other store, and the size of β is related to potential for cross-shopping between stores. Following Lal (1990), 0 < β < 1.

In Eq. 1, total market demand is equal to the number of stores when prices and effort levels are equal to zero. While this feature could appear undesirable, we (1) hold the number of stores constant when making comparisons between the independent (I) and company store (CS) channels, and (2) subsequently extend Eq. 1 to the case where adding additional stores may saturate the market (details are available from the authors upon request). Equation 1 is consistent with the pervasive forms in the literature. Consumers can accumulate product knowledge across stores but have limited access in memory to price information (Dickson and Sawyer 1990). We focus on marketing effort spillover effects in Eq. 1 for expositional reasons; however, we do subsequently allow for cross-price effects as well (the qualitative findings are unchanged).Footnote 8

2.2 Model analysis

A channel with independent retailers

Retailer s chooses retail prices and marketing efforts to maximize profits:

In Eq. 2, effort costs are quadratic as incremental investments in brand-specific service become increasingly costly (e.g., salespeople must be paid overtime, etc.). A similar assumption is made in Hauser et al. (1994). Note also that assuming cost, \(c{\text{ = }}e_{\text{s}}^{\text{2}} \), in Eq. 2 is equivalent to assuming diminishing returns to marketing effort \(e_s {\text{ }} = {\text{ }}\sqrt c \) in Eq. 1.Footnote 9

Proposition 1:

In the independent retailer channel (I), the equilibrium wholesale price, retail price, and marketing effort level are

Proof: See Appendix.

Equilibrium retail prices and marketing efforts at each store increase in β (sensitivity of demand to marketing effort provided by the competing store). Price is more sensitive to changes in this parameter than marketing effort is.

A channel with an independent retailer and a company store

Retailer 2 is now the company store. The manufacturer can endogenously choose to give brand assistance, a, to this store, and the company store is an independent profit center.Footnote 10 Demands at the independent retailer and the company store are as follows:

The independent retailer, company store, and manufacturer make decisions to maximize profits.Footnote 11 As with marketing effort, the cost of brand support is convex and equal to a 2. After substituting the demand functions into profits, we obtain the best response functions, derived demand functions, and Proposition 2.

Proposition 2:

In the company store channel (C), the equilibrium wholesale price, level of branding assistance, retail prices, and marketing effort levels are Footnote 12

where ψ = 11 − 6β − β 2.

Proof: See Appendix.

First, we compare price and marketing effort outcomes for the independent retailers across the two different channel arrangements. Second, we compare the decisions of the independent retailer and the company store within the company store channel. To facilitate exposition, we use the terms “maintenance” and “premium” as follows. “Maintenance” in the across-channel comparison means that the presence of a company store elevates the price or effort level of the independent retailer. If the independent retailer charges more or puts in more effort when operating under the CS channel, price or effort “maintenance” has been achieved. “Premium” in the within-channel comparison means that the company store charges more or invests in more effort, relative to the independent retailer. The findings from the comparisons are as follows (all mathematical details are in the Appendix and are obtained from Propositions 1 and 2).

-

Finding 1: strict price maintenance. The independent retailer charges more when competing against a company store; i.e., the price of the independent retailer is strictly higher in the company store channel than in the independent channel.

-

Finding 2: contingent effort maintenance. The independent retailer exerts more marketing effort when competing against a company store, provided that the effort spillover between outlets, β, is sufficiently high.

-

Finding 3: strict price premium. In the company store channel, the company store charges more than the independent retailer does.Footnote 13

-

Finding 4: strict effort premium. In the company store channel, the company exerts more marketing effort than the independent retailer does.

The potential for consumers to cross-shop and the fact that marketing effort at one store and manufacturer brand assistance can enhance demand at all retail outlets underlies these findings. Intuitively, since demand at a focal retailer increases in marketing effort at the other retailer, this leads to an outward shift in the demand curve, provided that the other retailer engages in marketing effort, which is costly. Optimal prices and marketing efforts therefore would increase accordingly. Since marketing effort is costly, competing independent retailers may choose to neglect it, leading to prices and effort levels that are undesirable (from the manufacturer’s point of view). In the CS channel structure, the company store “steps up” to provide effort at a level that the independent retailers cannot, and all channel members benefit accordingly.Footnote 14

In addition, all channel members in the CS structure benefit from higher profits provided that the effort spillover parameter is sufficiently high (see Appendix). Although we have not explicitly modeled the entry decision for the manufacturer store, the four findings above provide a rationale for entry. The presence of manufacturer stores in major city centers and shopping malls could be driven by a desire to achieve the four outcomes listed above.

2.3 Additional market features and considerations

The model just analyzed is deliberately parsimonious and focuses on marketing effort spillover (β) as the sole phenomenon of interest. To demonstrate that the findings are largely robust in richer settings, we briefly discuss four additional market features: differing retailing efficiency at company stores and independent retailers, price competition, consumer heterogeneity in brand preferences, and inter-brand competition. We emphasize the intuition and findings (mathematical details are again in the Appendix).

Differing retailing efficiency

McGuire and Staelin (1986, pp. 207–210) analyze a model where the independent retailer is assumed to have more experience and superior “expertise” in retailing. We therefore introduce a retailing cost, r m , at the company store so that the relevant retail margin is now (p 2 − w − r m ); r m is assumed equal to zero at the independent retailer. All four findings are qualitatively unchanged provided r m is sufficiently small, and the manufacturer and the retailers still earn more profits under CS if β is high enough. Furthermore, when the effort spillover effect, β, is high enough, the independent retailer makes higher profits when the company store is more efficient. Earlier, we cited legal cases of price squeezing by company stores; i.e., these stores use the benefit of their efficiency (lower retailing or wholesale costs) to undercut the independent retailer by pushing retail prices downward. In the CS channel and in markets with high positive effort spillover among outlets, this concern seems to be difficult to materialize.

Inter-store price competition

Another way to intensify the link between the two outlets is to consider price competition. Specifically, let q 1 = 1 − p 1 + θ(p 2 − p 1) + e 1 + β(e 2 + a) and q 2 = 1 − p 2 + θ(p 1 − p 2) + (e 2 + a) + βe 1 represent demands at the independent retailer and the company store, respectively. The addition of inter-store price competition leaves the qualitative findings unchanged; however, they are weakened, i.e., occur over a smaller range of the parameter space.

Shopper heterogeneity

The existence of company-owned retailers is sometimes attributed to the presence of a segment that is loyal to the brand. Assume, for example, that the company store attracts a segment of shoppers of size τ who only go to the company store when looking for the brand, e.g., a segment of shoppers buy Ralph Lauren suits from the Ralph Lauren store only. Demand functions are now q 1 = (1 − τ)[1 − p 1 + e 1 + β(e 2 + a)] and q 2 = (1 − τ)[1 − p 2 + (e 2 + a) + βe 1 ]+ τ[1 − p 2 + (e 2 + a)] at the independent retailer and the company store, respectively. The four findings again remain intact, provided that service spillover β is sufficiently high. A second form of heterogeneity allows that a segment of size λ does not value marketing effort or “service” and is unaffected by it. Here, demands are q 1 = (1 − λ)[1 − p 1 + e 1 + β(e 2 + a)] + λ(1 − p 1) and q 2 = (1 − λ)[1 − p 2 + (e 2 + a) + βe 1] + λ(1 − p 2). The findings are weakened but still go through provided β is sufficiently large.

Product assortment

The standard assumption of a single brand for each retailer does not dictate our maintenance and premium findings—the findings hold with broader product assortments at the independent retailer. To keep the setup parsimonious, we assume that marketing effort at the independent retailer applies collectively to the entire assortment; i.e., department stores in shopping malls either improve layout and salesperson quality overall or they do not. Service investments at multi-brand retailers are not technologically separable for individual brands. The independent retailer now carries two brands (brand 1 is supplied by the focal manufacturer who opens a company store and brand 2 is supplied by a competitor). Demand at retailer 1 for brand j (j = 1, 2) is q 1j , and demand at retailer 2 for brand 1 is q 2 as follows:

γ captures inter-brand competition (between brands 1 and 2) at the independent retailer. Retailer 2, the company store, carries brand 1 only. We find that the four findings continue to hold. Interestingly, the competing brand (brand 2) can also be better off as a result of the differentiating and spillover effects the company store has on brand 1. Again, effort spillover between outlets, β, is required to be sufficiently high.

3 Discussion and conclusion

We have shown one way that the company store channel affects the retail market. Independent retailers are induced to charge more and are also more willing to invest in marketing effort when the company store is present. This effect is likely to be helpful for branded goods that wish to maintain a certain level of image. More research is necessary for (at least) two reasons. First, brand manufacturers are opening more outlets, including flagship stores.Footnote 15 Second, by definition “CS arrangements” are pervasive on the Internet as all websites—whether retailer or manufacturer owned—are co-located and B2C retail sales continue to grow at a rapid rate (US Department of Commerce).

3.1 Anecdotal data on the effect of manufacturer-owned retail stores

We collected offline and online anecdotal data to check for preliminary evidence of the four main findings described previously.

Offline stores

Finding 1 (strict price maintenance) implies that an independent retailer charges more when it competes against a company store. A convenience sample of 47 prices for identical apparel and shoe stock keeping units (SKUs) was obtained from two shopping malls in a large metropolitan area in the USA. We noted (1) whether or not a specific SKU was selling on a temporary price promotion (yes/no), and (2) whether or not there was a company store in the mall (yes/no). Independence of the two dimensions is rejected (p < 0.05); independent retailers are indeed less likely to discount the brand when the company store is present, in accordance with finding 1.

Finding 3 (strict price premium) implies that in the CS channel the company store will charge more than the independent retailer. Prices at company stores and independent retailers physically co-located in a shopping center in a large US metro area were collected for a convenience sample of 23 identical SKUs from four product categories. By chance alone, the company store should charge a higher price half of the time, whereas it does so 74% of the time. The 95% confidence interval with continuity adjustment 0.5/n is [0.54, 0.94]; company stores charge higher prices than the independent stores more frequently than the chance benchmark and do not price-squeeze independent retailers, in line with finding 3.

The Internet

On the Internet, shoppers can easily move between independent retailers (e.g., http://www.revolveclothing.com) and manufacturer websites (e.g., http://www.truereligionbrandjeans.com) to gather price and non-price information about a brand (e.g., Liu et al. 2006). To examine findings 3 and 4, we obtained price and “marketing effort” data for 161 consumer products (unique SKUs) from 332 different websites; i.e., price and marketing effort was assessed for the same SKU at an independent retailer site and a manufacturer-owned site. Thirty-two independent assessors selected five different consumer goods product categories (e.g., cameras, printers, washing machines, etc.) and recorded prices listed at the manufacturer website and at the website of an independent retailer. They also assessed relative product-specific “marketing effort” (i.e., amount and quality of information) on a balanced five-point Likert scale (1 and 2 indicated “significantly more” and “slightly more” product information, respectively, at the manufacturer site and 3 “no difference”). In all, the 332 data points came from 161 SKUs in more than 20 different categories including personal computers, running shoes, computer software, digital cameras, household appliances, and fashion apparel.

The mean price for the 161 SKUs was $574.12 at manufacturer sites. This is significantly higher than the mean price of $543.79 at the independent sites (p < 0.01). For identical items, the manufacturer websites charged a price premium equal to about 6%, consistent with finding 3.Footnote 16 For identical items, the average rating for “relative marketing effort” at the manufacturer site relative to the independent site was 2.26. This indicates that the company site provides relatively more marketing effort (2.26 < 3.00 = “no difference”; p < 0.01), consistent with finding 4.

In summary, we have obtained four new findings that help explain why manufacturer-owned stores might be present in the retail market and implicitly why independent retailers might tolerate them. We hope to investigate other aspects of this phenomenon further in future research.

Notes

Not only is this market arrangement increasingly common in the physical world but also, by definition, pervasive on the Internet. All Internet retail sites—whether owned by manufacturers or independent retailers are “physically co-located.”

More detailed discussions of restraints on trade with respect to pricing and distribution can be found in Nagle and Holden (2002), and Coughlan et al. (2006). In June 2007, the US Supreme Court ruled that it was no longer appropriate to outright condemn resale price maintenance (see Stoll and Goldfein 2008 for details). We thank the editor for this update and reference.

For a more detailed analysis of these and other issues, see Bell et al. (2006).

In addition to articles based on formal economic models, a number of others explore retail outcomes from the perspective of organizational incentives and transaction cost analysis. Examples include Anderson (1985), Bradach (1997), and Brickley et al. (1991). A review of this literature is beyond the scope of our work. The interested reader is referred to Coughlan et al. (2006) and Tsay and Agrawal (2004). For a general economic model for durable goods, see Desai et al. (2004).

“Marketing effort” refers to brand-building activities by retailers. These include but are not limited to the hiring of knowledgeable salespeople, investments in advertising, and increases in the quality of in-store merchandizing and displays, etc. In economics, the term “service” is sometimes used in the same way. We use the two terms interchangeably.

We subsequently allow demand to depend on own and competitor prices, as well as own and competitive effort levels, i.e., q s = 1 − p s + θ(p 3−s− p s) + e s + βe 3−s. Since the qualitative results are unchanged, we focus first on the simpler setup in Eq. 1, which allows us to concentrate on the key variable of interest—marketing effort. We thank an anonymous reviewer for drawing our attention to this issue.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for suggesting this interpretation.

This assumption is line with institutional practice as determined by personal interviews with members of the Jay H. Baker Retailing Initiative, University of Pennsylvania. Equations 3a and 3b also assume that the base level of demand for the manufacturer’s brand is the same at both outlets.

For the moment, the company store is assumed as efficient as the independent retailer in the practice of retailing. McGuire and Staelin (1986), among others, call this assumption into question. In the next section, we allow the marginal retailing cost at the company store to differ from that at the independent store.

For simplicity, we use C to stand for CS in notations.

Recall the assumption that base demand is the same at both outlets (Eqs. 3a and 3b). If brand-specific demand at the company store is “very small” relative to that at the independent retailer, this result may not hold. Provided demand at the company store exceeds a critical value, the results do go through (details are available from the authors upon request). We thank an anonymous reviewer for this observation. In some instances, e.g., for Apple stores, an “equal intercept” assumption may even be conservative.

Interestingly, even if it is optimal for the two retailers to put in the same amount of effort as if the channel structure were independent (I), the manufacturer will still choose a positive level of brand assistance, a * > 0. As a result, the company store’s demand function is shifted out more than the independent retailer’s demand function. Consequently, the company store finds it best to put in more marketing effort and is also able to charge a higher price (findings 3 and 4). We thank an anonymous reviewer for this observation.

See http://www.icsc.org for recent trends including analyses of Apple, Prada, and other premium brands that have opened retail outlets and Kozinets et al. (2002) for a research perspective.

Finding 1 (strict price maintenance) cannot be tested directly in an Internet setting as there is no “parallel Internet” that contains independent retailer websites only (in the “real world,” there are malls that contain independent retailers but no company stores). Our conjecture, however, is that the presence of the company website (e.g., http://www.truereligionbrandjeans.com) helps to keep prices at the independent sites higher than they otherwise would be. The dataset is available from the authors upon request.

References

Anderson, E. T. (1985). The salesperson as outside agent or employee: a transaction cost analysis. Marketing Science, 4(3), 234–254.

Bell, D. R., Wang, Y. & Padmanabhan, V. (2006). An explanation for partial forward integration: Why manufacturers become marketers. Working Paper, The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania.

Bhardwaj, P. (2001). Delegating pricing decisions. Marketing Science, 20(2), 143–169.

Bradach, J. L. (1997). Using the plural form in management of restaurant chains. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42(2), 276–303.

Brickley, J. A., Dark, F. H., & Wesibach, M. S. (1991). An agency perspective on franchising. Financial Management, 20(Spring), 27–35.

Choi, S. C. (1991). Price competition in a channel structure with a common retailer. Marketing Science, 10(4), 271–296.

Chu, W., & Desai, P. S. (1995). Channel coordination mechanisms for customer satisfaction. Marketing Science, 14(4), 343–359.

Coleman Motor Corp. vs. Chrysler Corp., 525 f.2d (3rd cir. 1975).

Columbia Metal Culvert Co. vs. Kaiser Aluminum and Chemical Corp., 579 f.2d (3rd cir. 1978).

Coughlan, A. T. (1985). Competition and cooperation in marketing channel choice: theory and application. Marketing Science, 4(2), 110–129.

Coughlan, A. T., Anderson, E. T., Stern, L. W., & El-Ansary, A. I. (2006). Marketing channels (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Desai, P., Koenigsberg, O., & Purohit, D. (2004). Strategic decentralization and channel coordination. Quantitative Marketing and Economics, 2(1), 5–22.

Dickson, P., & Sawyer, A. G. (1990). The price knowledge and search of supermarket shoppers. Journal of Marketing, 54(July), 42–53.

Eliashberg, J., & Michie, D. A. (1984). Multiple business goals sets as determinants of marketing channel conflict: an empirical study. Journal of Marketing Research, 21(February), 75–88.

Hauser, J. R., Simester, D. I., & Wernerfelt, B. (1994). Customer satisfaction incentives. Marketing Science, 13(4), 327–350.

Ingene, C. A., & Parry, M. E. (1995). Channel coordination when retailers compete. Marketing Science, 14(4), 360–377.

Ingene, C. A., & Parry, M. E. (1998). Manufacturer-optimal wholesale pricing when retailers compete. Marketing Letters, 9(1), 65–77.

Kozinets, R. V., Sherry, J. F., DeBerry-Spence, B., Duhachek, A., Nuttavuthisit, K., & Storm, D. (2002). Themed flagship brand stores in the new millennium: theory, practice, prospects. Journal of Retailing, 78(1), 17–29.

Lal, R. (1990). Improving channel coordination through franchising. Marketing Science, 9(4), 299–318.

Liu, Y., Zhang, Z. J., & Gupta, S. (2006). Note on self-restraint as an online entry-deterrence strategy. Management Science, 52(11), 1799–1809.

McGuire, T. W., & Staelin, R. (1983). An industry equilibrium analysis of downstream vertical integration. Marketing Science, 2(2), 161–191.

McGuire, T. W., & Staelin, R. (1986). Channel efficiency, incentive compatibility, transfer pricing and market structure: an equilibrium analysis of channel relationships. In L. P. Bucklin, & J. M. Carman (Eds.), Research in marketing: Distribution channels and institutions. Greenwich, CN: JAI Press.

Moorthy, K. S. (1987). Strategic decentralization in channels. Marketing Science, 7(4), 335–355.

Nagle, T. T., & Holden, R. K. (2002). The strategy and tactics of pricing: a guide to profitable decision making (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Raju, J. S., Sethuraman, R., & Dhar, S. K. (1995). The introduction and performance of store brands. Management Science, 41(6), 957–978.

Stoll, N. R., & Goldfein, S. (2008). ‘Discount Pricing’ Act: direct rebuke to ‘Leegin’. New York Law Journal, 239(52), 3.

Trivedi, M. (1998). Distribution channels: an extension of exclusive retailership. Management Science, 44(July), 896–909.

Tsay, A. A., & Agrawal, N. (2004). Modeling conflict and coordination in multi-channel distribution systems: a review. In D. Simchi-Levi, S. D. Wu, & Z. M. Shen (Eds.), Handbook of quantitative supply chain analysis. Norwell, MA: Kluwer.

U.S. vs. Aluminum Co. of America, 148 f. 2d 416 (2nd cir. 1945).

Winter, R. A. (1993). Vertical control and price versus non-price competition. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108(1), 61–76.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Christophe Van den Bulte, Chakravarthi Narasimhan, and John Zhang for their comments. They are also grateful to Jagmohan Raju for his advice and to Aileen Kim for research assistance. The authors thank Singapore Management University and Fudan University for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Proof of Proposition 1

After substituting the demand functions into profits and taking partial derivatives with respect to the decision variables, we have the following first-order conditions:

Solving the first-order conditions simultaneously gives the best response functions \( \widehat{p}_{1} = \widehat{p}_{2} = \frac{{2 + w{\left( {1 - \beta } \right)}}} {{3 - \beta }} \) and \( \widehat{e}_{1} = \widehat{e}_{2} = \frac{{1 - w}} {{3 - \beta }} \). Alternatively, we can get the same response functions by applying symmetry p 1 = p 2 and e 1 = e 2 in the first two first-order conditions. It is easy to show that the second-order conditions are satisfied. Substituting the best response functions into the demand functions yields the derived demand functions q 1 *(w) and q 2 *(w). The manufacturer chooses the wholesale price w to maximize profits

The first-order condition \( \frac{{\partial \prod ^{M} }} {{\partial w}} = 0 \) leads to the equilibrium \( w^{*} = \frac{1} {2} \). Thus, we can get \( p^{*}_{1} {\left( I \right)} = p^{*}_{2} {\left( I \right)} = \frac{1} {2} + \frac{1} {{3 - \beta }} \), \( e^{*}_{2} {\left( I \right)} = e^{*}_{2} {\left( I \right)} = \frac{1} {{2{\left( {3 - \beta } \right)}}} \), \( q^{*}_{1} {\left( I \right)} = q^{*}_{2} {\left( I \right)} = \frac{1} {{3 - \beta }} \), \( \prod ^{{R^{*}_{1} }} {\left( I \right)} = \prod ^{{R^{*}_{2} }} {\left( I \right)} = \frac{3} {{4{\left( {3 - \beta } \right)}^{2} }} \), and \( \prod ^{{M^{*} }} {\left( I \right)} = \frac{1} {{3 - \beta }} \).

1.2 Proof of Proposition 2

The demand functions at independent retailer 1 and company store 2 are

where the manufacturer provides branding support a to the company store. The independent retailer and company store choose retail prices and marketing efforts to maximize profits

After substituting the demand functions into profits and taking partial derivatives with respect to the decision variables, we have the following first-order conditions:

Solving these simultaneously yields the best response functions

Substituting the best response functions into the demand functions provides the derived demand functions q 1 *(w, a) and q 2 *(w, a). The manufacturer chooses wholesale price w and brand support a to maximize profits

where the cost of providing brand support a is a 2 to the manufacturer. In theory, the manufacturer can choose any a ⩾ 0. If a = 0, we have the case of no branding support at all so that the profits for company store will be same as \( \prod ^{{R^{*}_{2} }} {\left( I \right)} \). Solving the first-order conditions \( \frac{{\partial \prod ^{M} }} {{\partial w}} = 0 \) and \( \frac{{\partial \prod ^{M} }} {{\partial a}} = 0 \) leads to the equilibrium wholesale price \( w^{*} {\left( C \right)} = \frac{{2{\left( {3 - \beta } \right)}}}{{11 - 6\beta - \beta ^{2} }}\) and optimal brand support \( a^{*} {\left( C \right)} = \frac{{2{\left( {1 + \beta } \right)}}}{{11 - 6\beta - \beta ^{2} }} \), which then are used to get retail prices and marketing efforts for the independent retailer \(p_1^* \left( C \right) = \frac{{4\left( {7 + \beta } \right)}}{{\left( {3 + \beta } \right)\left( {11 - 6\beta - \beta ^2 } \right)}}\) and \(e_1^* \left( C \right) = \frac{{5 + 2\beta + \beta ^2 }}{{\left( {3 + \beta } \right)\left( {11 - 6\beta - \beta ^2 } \right)}}\) and for the company store \(p_{2}^{*} \left( C \right) = \frac{{4\left( {8 + \beta - \beta ^{2} } \right)}} {{\left( {3 + \beta } \right) \left( {11 - 6\beta - \beta ^{2} } \right)}}\) and \( e_2^ * \left( C \right) = \frac{{7 + 2\beta - \beta ^2 }} {{\left( {3 + \beta } \right)\left( {11 - 6\beta - \beta ^2 } \right)}} \), respectively. The profits for independent retailer, company store, and manufacturer are \(\prod ^{R_1^* } \left( C \right) = \frac{{3\left( {5 + 2\beta + \beta ^2 } \right)^2 }}{{\left( {3 + \beta } \right)^2 \left( {11 - 6\beta - \beta ^2 } \right)^2 }}\), \(\prod ^{R_2^* } \left( C \right) = \frac{{3\left( {7 + 2\beta - \beta ^2 } \right)^2 }}{{\left( {3 + \beta } \right)^2 \left( {11 - 6\beta - \beta ^2 } \right)^2 }}\) and \( \prod ^{M} {\left( C \right)} = \frac{4} {{11 - 6\beta - \beta ^{2} }} \), respectively. The demands at independent retailer and company store are \(q_1^* \left( C \right) = \frac{{2\left( {5 + 2\beta + \beta ^2 } \right)}}{{\left( {3 + \beta } \right)\left( {11 - 6\beta - \beta ^2 } \right)}}\) and \(q_2^* \left( C \right) = \frac{{2\left( {7 + 2\beta - \beta ^2 } \right)}}{{\left( {3 + \beta } \right)\left( {11 - 6\beta - \beta ^2 } \right)}}\).

1.3 Proof that Manufacturer and Retailer Profits Can Increase

Provided that β is sufficiently high, all channel members can be better off under CS channel. Note that, without branding support, the company store’s profits would be \( \prod ^{{R^{*}_{2} }} {\left( I \right)} \). Each party benefits as follows

-

Company store: \(\prod ^{R_2^* } \left( C \right) - \prod ^{R_2^* } \left( I \right) = \frac{{3\left( {7 + 2\beta - \beta ^2 } \right)^2 }}{{\left( {3 + \beta } \right)^2 \left( {11 - 6\beta - \beta ^2 } \right)^2 }} - \frac{3}{{4\left( {3 - \beta } \right)^2 }} = \frac{{3\left( {1 + \beta } \right)\left( {9 - 4\beta + 3\beta ^2 } \right)\left( {75 - 9\beta - 19\beta ^2 + \beta ^3 } \right)}}{{4\left( {3 + \beta } \right)^2 \left( {3 - \beta } \right)^2 \left( {11 - 6\beta - \beta ^2 } \right)^2 }} > 0\)

-

Manufacturer: \( \prod ^{M} {\left( C \right)} - \prod ^{M} {\left( I \right)} = \frac{4} {{11 - 6\beta - \beta ^{2} }} - \frac{1} {{3 - \beta }} = \frac{{1 + 2\beta + \beta ^{2} }} {{{\left( {3 - \beta } \right)}{\left( {11 - 6\beta - \beta ^{2} } \right)}}} > 0 \)

-

Independent retailer:\(\begin{array}{*{20}c} {\prod ^{R_1^* } \left( C \right) - \prod ^{R_1^* } \left( I \right) = \frac{{3\left( {5 + 2\beta + \beta ^2 } \right)^2 }}{{\left( {3 + \beta } \right)^2 \left( {11 - 6\beta - \beta ^2 } \right)^2 }} - \frac{3}{{4\left( {3 - \beta } \right)^2 }}} \\ { = \frac{{3\left( {1 + \beta } \right)\left( { - 3 + 12\beta - \beta ^2 } \right)\left( {63 - 5\beta - 7\beta ^2 - 3\beta ^3 } \right)}}{{4\left( {3 + \beta } \right)^2 \left( {3 - \beta } \right)^2 \left( {11 - 6\beta - \beta ^2 } \right)^2 }} > 0,\;{\text{if }} - 3 + 12\beta - \beta ^2 > 0{\text{ i}}{\text{.e}}{\text{., }}\beta > 6 - \sqrt {33} \approx 0.255437} \\ \end{array} \)

1.4 Retailing Efficiency and Price Competition Across Stores

1.4.1 Retailing Efficiency

The equilibrium demand at company store is \( q^{*}_{2} {\left( C \right)} = \frac{{2{\left( {7 + 2\beta - \beta ^{2} - {\left( {9 - 2\beta - \beta ^{2} } \right)}} \right)}r_{m} }} {{{\left( {3 + \beta } \right)}{\left( {11 - 6\beta - \beta ^{2} } \right)}}} \), and thus, q 2 *(C) > 0 implies that \( r_{m} < r_{{m1}} = \frac{{7 + 2\beta - \beta ^{2} }}{{9 - 2\beta - \beta ^{2} }} \). (1) Price maintenance: \(p^{*}_{1} {\left( C \right)} - p^{*}_{1} {\left( I \right)} = \frac{{4{\left( {7 + \beta } \right)} - {\left( {3 + 8\beta + \beta ^{2} } \right)}r_{m} }}{{{\left( {3 + \beta } \right)}{\left( {11 - 6\beta - \beta ^{2} } \right)}}} - {\left( {\frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{{3 - \beta }}} \right)} = \frac{{{\left( {1 + \beta } \right)}{\left( {3 + 33\beta - 3\beta ^{2} - \beta ^{3} } \right)} - 2{\left( {3 - \beta } \right)}{\left( {3 + 8\beta + \beta ^{2} } \right)}r_{m} }}{{2{\left( {3 + \beta } \right)}{\left( {3 - \beta } \right)}{\left( {11 - 6\beta - \beta ^{2} } \right)}}} > 0\) for all β and \(0 \leqslant r_{m} < r_{{m2}} = \frac{{{\left( {1 + \beta } \right)}{\left( {3 + 33\beta - 3\beta ^{2} - \beta ^{3} } \right)}}}{{2{\left( {3 - \beta } \right)}{\left( {3 + 8\beta + \beta ^{2} } \right)}}}\). (2) Effort maintenance: \(e^{*}_{1} {\left( C \right)} - e^{*}_{1} {\left( I \right)} = \frac{{5 + 2\beta + \beta ^{2} - {\left( {3 - 4\beta - \beta ^{3} } \right)}r_{m} }}{{{\left( {3 + \beta } \right)}{\left( {11 - 6\beta - \beta ^{2} } \right)}}} - \frac{1}{{2{\left( {3 - \beta } \right)}}} = \frac{{{\left( {1 + \beta } \right)}{\left( { - 3 + 12\beta - \beta ^{2} } \right)} - 2{\left( {3 - \beta } \right)}{\left( { - 3 + 4\beta + \beta ^{2} } \right)}r_{m} }}{{2{\left( {3 + \beta } \right)}{\left( {3 - \beta } \right)}{\left( {11 - 6\beta - \beta ^{2} } \right)}}} > 0 \) if (a) \(6 - \sqrt {33} < \beta \leqslant \sqrt {7 - 2}\) and r m ≥ 0, or (b) \(\beta < {\sqrt 7 } - 2\) and 0 ≤ r m ≤ r m1, where \( r_{{m1}} = \frac{{7 + 2\beta - \beta ^{2} }}{{9 - 2\beta - \beta ^{2} }} < \frac{{{\left( {1 + \beta } \right)}{\left( { - 3 + 12\beta - \beta ^{2} } \right)}}}{{2{\left( {3 - \beta } \right)}{\left( { - 3 + 4\beta + \beta ^{2} } \right)}}}\) when \(\beta > {\sqrt 7 } - 2\). (3) Price premium: \(p^{*}_{2} {\left( C \right)} - p^{*}_{1} {\left( C \right)} = \frac{{4{\left( {8 + \beta - \beta ^{2} } \right)} + {\left( {6 - 3\beta - 6\beta ^{2} - \beta ^{3} } \right)}r_{m} }}{{{\left( {3 + \beta } \right)}{\left( {11 - 6\beta - \beta ^{2} } \right)}}} - \frac{{4{\left( {7 + \beta } \right)} - {\left( {3 + 8\beta + \beta ^{2} } \right)}r_{m} }}{{{\left( {3 + \beta } \right)}{\left( {11 - 6\beta - \beta ^{2} } \right)}}} = \frac{{{\left( {1 + \beta } \right)}{\left[ {4 - 4\beta + {\left( {9 - 4\beta - \beta ^{2} } \right)}r_{m} } \right]}}}{{{\left( {3 + \beta } \right)}{\left( {11 - 6\beta - \beta ^{2} } \right)}}} > 0\) for all β and r m . (4) Effort premium: \(e^{*}_{2} {\left( C \right)} - e^{*}_{1} {\left( C \right)} = \frac{{7 + 2\beta - \beta ^{2} - {\left( {9 - 2\beta - \beta ^{3} } \right)}r_{m} }}{{{\left( {3 + \beta } \right)}{\left( {11 - 6\beta - \beta ^{2} } \right)}}} - \frac{{5 + 2\beta + \beta ^{2} - {\left( {3 - 4\beta - \beta ^{3} } \right)}r_{m} }}{{{\left( {3 + \beta } \right)}{\left( {11 - 6\beta - \beta ^{2} } \right)}}} = \frac{{2{\left[ {1 - \beta ^{2} - {\left( {6 - 3\beta - \beta ^{2} } \right)}r_{m} } \right]}}}{{{\left( {3 + \beta } \right)}{\left( {11 - 6\beta - \beta ^{2} } \right)}}} > 0\) for all β and \(0 \leqslant r_{m} < r_{{m3}} = \frac{{{\left( {1 - \beta ^{2} } \right)}}}{{6 - 3\beta - \beta ^{2} }}\).

The company store’s profits: \(\prod ^{{R^{*}_{2} }} {\left( C \right)} - \prod ^{{R^{*}_{2} }} {\left( I \right)} = \frac{{3{\left[ {7 + 2\beta - \beta ^{2} - {\left( {9 - 2\beta r_{m} - \beta ^{2} } \right)}r_{m} } \right]}^{2} }}{{{\left( {3 + \beta } \right)}^{2} {\left( {11 - 6\beta - \beta ^{2} } \right)}^{2} }} - \frac{3}{{4{\left( {3 - \beta } \right)}^{2} }} = {\frac{3}{4}\beta _{1} \beta _{2} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\frac{3}{4}\beta _{1} \beta _{2} } {{\left[ {{\left( {3 + \beta } \right)}^{2} {\left( {3 - \beta } \right)}^{2} {\left( {11 - 6\beta - \beta ^{2} } \right)}^{2} } \right]}}}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {{\left[ {{\left( {3 + \beta } \right)}^{2} {\left( {3 - \beta } \right)}^{2} {\left( {11 - 6\beta - \beta ^{2} } \right)}^{2} } \right]}} > 0\) if \(r_{m} < r_{{m5}} = \frac{{9 + 5\beta - \beta ^{2} + 3\beta ^{3} }}{{54 - 30\beta - 2\beta ^{2} + 2\beta ^{3} }}\), where \(\beta _{1} = 9 + 5\beta - \beta ^{2} + 3\beta ^{3} - {\left( {54 - 30\beta - 2\beta ^{2} + 2\beta ^{3} } \right)}r_{m} \) and \( \beta _{2} = 75 - 9\beta - 19\beta ^{2} + \beta ^{3} - {\left( {54 - 30\beta - 2\beta ^{2} + 2\beta ^{3} } \right)}r_{m} \). The manufacturer’s profits: \( {\prod {^{{M * }} } }{\left( C \right)} - {\prod {^{{M * }} } }{\left( I \right)} = \frac{{{\left( {2 - r_{m} } \right)}^{2} }} {{11 - 6\beta - \beta ^{2} }} - \frac{1} {{3 - \beta }} = \frac{{1 + 2\beta + \beta ^{2} - {\left( {12 - 4\beta } \right)}r_{m} + {\left( {3 - \beta } \right)}r^{2}_{m} }} {{{\left( {3 - \beta } \right)}{\left( {11 - 6\beta - \beta ^{2} } \right)}}} > 0 \) if \( r_{m} < r_{{m4}} = \frac{{6 - 2\beta - {\sqrt {33 - 29 + 3\beta ^{2} + \beta ^{3} } }}} {{3 - \beta }} \). The independent retailer’s profits: \({\prod {^{{R^{ * }_{1} }} } }{\left( C \right)} - {\prod {^{{R^{ * }_{1} }} } }{\left( I \right)} = \frac{{3{\left[ {5 + 2\beta + \beta ^{2} - {\left( { - 3 + 4\beta + \beta ^{2} } \right)}r_{m} } \right]}^{2} }}{{{\left( {3 + \beta } \right)}^{2} {\left( {11 - 6\beta - \beta ^{2} } \right)}^{2} }} - \frac{3}{{4{\left( {3 - \beta } \right)}^{2} }} > 0\) if (a) \(6 - {\sqrt {33} } < \beta \leqslant {\sqrt 7 } - 2\) and any r m > 0 or (b) \(\beta > {\sqrt 7 } - 2\) and \( r_{m} < r_{{m6}} = \frac{{{\left( {1 + \beta } \right)}{\left( { - 3 + 12\beta - \beta ^{2} } \right)}}} {{2{\left( { - 9 + 15\beta - \beta ^{2} - \beta ^{3} } \right)}}} \). Since r m3 < r m2 < r m1 and r m4 < r m5, if r m is sufficiently small (i.e., \( r_{m} < \ifmmode\expandafter\hat\else\expandafter\^\fi{r}_{m} = \min {\left\{ {r_{{m3}} ,r_{{m4}} ,r_{{m6}} } \right\}} \)) and service spillover is sufficiently high (i.e., \(\beta > 6 - \sqrt {33} \)), all four price and marketing effort results derived from the basic model remain qualitatively unchanged, and all channel members are better off under co-located channel. The branding support that the company store receives is \(a^{ * } {\left( C \right)} = \frac{{{\left( {1 + \beta } \right)}{\left( {2 - r_{m} } \right)}}}{{11 - 6\beta - \beta ^{2} }},\), where a*(C) decreases as r m increases.

Profits at the independent retailer are \({\prod {^{{R^{ * }_{1} }} } }{\left( C \right)} = \frac{{3{\left[ {5 + 2\beta + \beta ^{2} + {\left( {3 - 4\beta - \beta ^{2} } \right)}r_{m} } \right]}^{2} }}{{{\left( {3 + \beta } \right)}^{2} {\left( {11 - 6\beta - \beta ^{2} } \right)}}}\), and the sign of \( \frac{{\partial {\prod {^{{R^{ * }_{1} }} {\left( C \right)}} }}} {{\partial r_{m} }} \) is the same as the sign of 3–4β–β 2. Thus, \( \frac{{\partial {\prod {^{{R^{ * }_{1} }} {\left( C \right)}} }}} {{\partial r_{m} }} \) < 0 if 3–4β–β 2 < 0, i.e., \( \beta > {\sqrt 7 } - 2 \), where a more efficient co-located company store is beneficial for the independent retailer.

1.4.2 Price Competition Across Stores

(1) Price maintenance: \(p^{ * }_{1} {\left( C \right)} - p^{ * }_{1} {\left( I \right)} = \frac{{2{\left( {14 + 2\beta + 35\theta - 4\beta \theta + \beta ^{2} \theta + 12\theta ^{2} } \right)}}}{{\psi _{1} }} - {\left( {\frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{{3 - \beta + 2\theta }}} \right)} > 0\) for any 0 < β < 1 and 0 < θ < 1, where ψ 1 = (3 + β + 6θ)(11–6β–β 2 + 7θ–2βθ–β 2 θ). (2) Effort maintenance: \( e^{ * }_{1} {\left( C \right)} - e^{ * }_{1} {\left( I \right)} = \frac{{5 + 2\beta + \beta ^{2} + 11\theta + \beta ^{2} \theta }} {{\psi _{1} }} - \frac{1} {{2{\left( {3 - \beta + 2\theta } \right)}}} = \frac{{{\left( {1 + \beta } \right)}{\left( {1 + \theta } \right)}{\left( { - 3 + 12\beta - \beta ^{2} - 2\theta + 10\beta \theta } \right)}}} {{2{\left( {3 - \beta + 2\theta } \right)}\psi _{1} }} > 0 \) if \( \beta > \underset{\raise0.3em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle-}$}}{\beta } {\left( \theta \right)} \) where \( \underset{\raise0.3em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle-}$}}{\beta } {\left( \theta \right)} \) is defined by the implicit function \( - 3 + 12\underset{\raise0.3em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle-}$}}{\beta } {\left( \theta \right)} - {\left[ {\underset{\raise0.3em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle-}$}}{\beta } {\left( \theta \right)}} \right]}^{2} + 2\theta + 10\underset{\raise0.3em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle-}$}}{\beta } {\left( \theta \right)}\theta = 0.\frac{{\partial \beta {\left( \theta \right)}}}{{\partial \theta }} = - \frac{{2{\left( {1 + 5\beta } \right)}}}{{2{\left( {6 - \beta + 5\theta } \right)}}} < 0, \) and thus, the threshold value \( \underset{\raise0.3em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle-}$}}{\beta } {\left( \theta \right)} \) decreases as θ increases.

(3) Price premium: \(p^{ * }_{2} {\left( C \right)} - p^{ * }_{1} {\left( C \right)} = \frac{{2{\left( {16 + 2\beta - 2\beta ^{2} + 37\theta - 4\beta \theta - \beta ^{2} \theta + 12\theta ^{2} } \right)}}}{{\psi _{1} }} - \frac{{2{\left( {14 + 2\beta + 35\theta - 4\beta \theta + \beta ^{2} \theta + 12\theta ^{2} } \right)}}}{{\psi _{1} }} = \frac{{4\beta ^{2} + 4\theta - 4\beta ^{2} \theta }}{{\psi _{1} }} > 0\). (4) Effort premium: \( e^{ * }_{2} {\left( C \right)} - e^{ * }_{1} {\left( C \right)} = \frac{{7 + 2\beta - \beta ^{2} + 13\theta - \beta ^{2} \theta }} {{\psi _{1} }} - \frac{{5 + 2\beta + \beta ^{2} + 11\theta + \beta ^{2} \theta }} {{\psi _{1} }} = \frac{{2{\left( {1 - \beta ^{2} } \right)}{\left( {1 + \theta } \right)}}} {{\psi _{1} }} > 0 \). Take first derivative respect to θ, and it can be shown that, when β is sufficiently high, the differences of (1) through (4) all decrease. Therefore, with price competition across stores, the qualitative findings from the basic model remain unchanged; however, the price/effort premium and maintenance results are weakened.

The company store’s profits: \( {\prod {^{{R^{ * }_{2} }} } }{\left( C \right)} - {\prod {^{{R^{ * }_{2} }} } }{\left( I \right)} = \frac{{{\left( {3 + 4\theta } \right)}{\left( {7 + 2\beta - \beta ^{2} + 13\theta - \beta ^{2} \theta } \right)}^{2} }} {{\psi ^{2}_{1} }} - \frac{{3 + 4\theta }} {{4{\left( {3 - \beta + 2\theta } \right)}^{2} }} > 0 \). The manufacturer’s profits: \( {\prod {^{{M * }} {\left( C \right)} - {\prod {^{{M * }} } }{\left( I \right)}} } = \frac{{4{\left( {1 + \theta } \right)}}} {{11 - 6\beta - \beta ^{2} + 7\theta - 2\beta \theta - \beta ^{2} \theta }} - \frac{{1 + \theta }} {{3 - \beta + 2\theta }} > 0 \). The independent retailer’s profits: \( {\prod {^{{R^{ * }_{1} }} } }{\left( C \right)} - {\prod {^{{R^{ * }_{1} }} } }{\left( I \right)} = \frac{{{\left( {3 + 4\theta } \right)}{\left( {5 + 2\beta + \beta ^{2} + 11\theta + \beta ^{2} \theta } \right)}^{2} }} {{\psi ^{2}_{1} }} - \frac{{3 + 4\theta }} {{4{\left( {3 - \beta + 2\theta } \right)}^{2} }} \) which has the same sign as −3 + 12β – β 2 + 2θ + 10βθ. Thus, \( {\prod {^{{R^{ * }_{1} }} } }{\left( C \right)} - {\prod {^{{R^{ * }_{1} }} } }{\left( I \right)} > 0 \) if \( \beta > \underset{\raise0.3em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle-}$}}{\beta } {\left( \theta \right)} \), where \( \underset{\raise0.3em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle-}$}}{\beta } {\left( \theta \right)} \) has been defined previously. The branding support that the company store receives is \( a^{ * } {\left( C \right)} = \frac{{2{\left( {1 + \beta } \right)}{\left( {1 + \theta } \right)}}} {{11 - 6\beta - \beta ^{2} + 7\theta - 2\beta \theta - \beta ^{2} \theta }} \).

1.5 Consumer Heterogeneity

1.5.1 Consumer Heterogeneity in Brand Loyalty

(1) Price maintenance: \( p^{ * }_{1} {\left( C \right)} - p^{ * }_{1} {\left( I \right)} = \frac{{4{\left( {3 + \beta } \right)}{\left( {7 + \beta } \right)} - \beta \tau {\left( {15 - 6\beta - \beta ^{2} + \beta ^{2} \tau } \right)}}} {{\psi _{2} }} - {\left( {\frac{1} {2} + \frac{1} {{3 - \beta }}} \right)} > 0 \) for any 0 < β < 1 and 0 < τ < 1, where ψ 2 = 99 + 12β – 34β 2 – 12β 3 − β 4 − 18βτ + 18β 2 τ + 14β 3 τ + 2β 4 τ − 2β 3 τ 2 − β 4 τ 2. (2) Effort maintenance: \( e^{ * }_{1} {\left( C \right)} - e^{ * }_{1} {\left( I \right)} = \frac{{15 + 11\beta + 5\beta ^{2} + \beta ^{3} - 3\beta \tau - \beta ^{3} \tau }} {{\psi _{2} }} - \frac{1} {{2{\left( {3 - \beta } \right)}}} = \frac{{ - 9 + 24\beta + 24\beta ^{2} + 8\beta ^{3} - \beta ^{4} - 12\beta ^{2} \tau - 20\beta ^{3} \tau + 2\beta ^{3} \tau ^{2} + \beta ^{4} \tau ^{2} }} {{2{\left( {3 - \beta } \right)}\psi _{2} }} > 0 \) if \( \beta > \underset{\raise0.3em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle-}$}}{\beta } {\left( \tau \right)} \) where \( \underset{\raise0.3em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle-}$}}{\beta } {\left( \tau \right)} \) is defined by the implicit function \( - 9 + 24\underset{\raise0.3em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle-}$}}{\beta } {\left( \tau \right)} + 42{\left[ {\underset{\raise0.3em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle-}$}}{\beta } {\left( \tau \right)}} \right]}^{2} + 8{\left[ {\underset{\raise0.3em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle-}$}}{\beta } {\left( \tau \right)}} \right]}^{3} - {\left[ {\underset{\raise0.3em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle-}$}}{\beta } {\left( \tau \right)}} \right]}^{4} - 12{\left[ {\underset{\raise0.3em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle-}$}}{\beta } {\left( \tau \right)}} \right]}^{2} \tau - 20{\left[ {\underset{\raise0.3em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle-}$}}{\beta } {\left( \tau \right)}} \right]}^{3} \tau + 2{\left[ {\underset{\raise0.3em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle-}$}}{\beta } {\left( \tau \right)}} \right]}^{3} \tau ^{2} {\left[ {\underset{\raise0.3em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle-}$}}{\beta } {\left( \tau \right)}} \right]}^{4} \tau ^{2} = 0\), where \( \frac{{\partial \underset{\raise0.3em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle-}$}}{\beta } {\left( \tau \right)}}} {{\partial \tau }} > 0 \). (3) Price premium: \( p^{ * }_{2} {\left( C \right)} - p^{ * }_{1} {\left( C \right)} = \frac{{96 + 44\beta - 8\beta ^{2} - 4\beta ^{3} - 27\beta \tau - 2\beta ^{2} \tau + 5\beta ^{3} \tau + 2\beta ^{2} \tau ^{2} - \beta ^{3} \tau ^{2} }} {{\psi _{2} }} - \frac{{4{\left( {3 + \beta } \right)}{\left( {7 + \beta } \right)} - \beta \tau {\left( {15 - 6\beta - \beta ^{2} + \beta ^{2} \tau } \right)}}} {{\psi _{2} }} > 0 \) if β is high enough. (4) Effort premium: \(e^{ * }_{2} {\left( C \right)} - e^{ * }_{1} {\left( C \right)} = \frac{{21 + 13\beta - \beta ^{2} - \beta ^{3} - 9\beta \tau - 4\beta ^{2} \tau + \beta ^{3} \tau + \beta ^{2} \tau ^{2} }}{{\psi _{2} }} - \frac{{15 + 11\beta + 5\beta ^{2} + \beta ^{3} - 3\beta \tau - \beta ^{3} \tau }}{{\psi _{2} }} > 0\) if β is high enough. Take first derivative respect to τ, and it can be shown that, when β is sufficiently high, the differences of (1) through (4) all decrease. Therefore, the qualitative findings from the basic model remain unchanged; however, the price/effort premium and maintenance results are weakened.

The branding support that the company store receives is \( a^{ * } {\left( C \right)} = \frac{{{\left( {6 + 2\beta - \beta \tau } \right)}{\left( {3 + 4\beta + \beta ^{2} - \beta ^{2} \tau } \right)}}} {{\psi _{2} }} \). The company store’s profits: \({\prod {^{{R^{ * }_{2} }} } }{\left( C \right)} - {\prod {^{{R^{ * }_{2} }} } }{\left( I \right)} = \frac{{3{\left( {21 + 13\beta - \beta ^{2} - \beta ^{3} - 9\beta \tau - 4\beta ^{2} \tau + \beta ^{3} \tau + \beta ^{2} \tau ^{2} } \right)}^{2} }}{{\psi ^{2}_{2} }} - \frac{3}{{4{\left( {3 - \beta } \right)}^{2} }} > 0\) and \( \frac{{{\prod {^{{R^{ * }_{2} }} } }{\left( C \right)} - {\prod {^{{R^{ * }_{2} }} } }{\left( I \right)}}} {{\partial \tau }} < 0 \). The manufacturer’s profits: \({\prod {^{{M * }} } }{\left( C \right)} - {\prod {^{{M * }} {\left( I \right)} = \frac{{{\left( {6 + 2\beta - \beta \tau } \right)}^{2} }}{{\psi _{{^{2} }} }}} } - \frac{1}{{3 - \beta }} > 0\) and \( \frac{{\partial {\prod {^{{M * }} {\left( C \right)} - {\prod {^{{M * }} } }{\left( I \right)}} }}} {{\partial \tau }} < 0 \). Therefore, having a larger segment of loyal consumers is not beneficial for the manufacturer and the company store.

The independent retailer’s profits: \({\prod {^{{R^{ * }_{1} }} } }{\left( C \right)} - {\prod {^{{R^{ * }_{1} }} } }{\left( I \right)} = \frac{{3{\left( {15 + 11\beta + 5\beta ^{2} + \beta ^{3} - 3\beta \tau - \beta ^{3} \tau } \right)}^{2} }}{{\psi ^{2}_{2} }} - \frac{3}{{4{\left( {3 - \beta } \right)}^{2} }}\), which has the same sign as F 1(β, τ) = −9 + 24β + 42β 2 + 8β 3 − β 4 − 12β 2 τ − 20β 3 τ + 2β 3 τ 2 + β 4 τ 2. Thus, \( {\prod {^{{R^{ * }_{1} }} } }{\left( C \right)} - {\prod {^{{R^{ * }_{1} }} } }{\left( I \right)} > 0 \) if \( \beta > \underset{\raise0.3em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle-}$}}{\beta } _{2} {\left( \tau \right)} \) where \(F_{1} {\left( {\underline{{\beta _{1} }} {\left( \tau \right)},\tau } \right)} = 0,\,0.25 < \underline{{\beta _{1} }} {\left( \tau \right)} < 0.3\) for any 0 < τ < 1.

1.5.2 Consumer Heterogeneity in the Value Placed on Marketing Service

(1) Price maintenance: \(p^{ * }_{1} {\left( C \right)} - p^{ * }_{1} {\left( I \right)} = \frac{{2{\left[ {14 + 2\beta + {\left( {2 - \lambda } \right)}\lambda {\left( {9 - 2\beta + \beta ^{2} + 2\lambda - 2\beta ^{2} \lambda - \lambda ^{2} + \beta ^{2} \lambda ^{2} } \right)}} \right]}}}{{\psi _{3} \psi _{4} }} - {\left( {\frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{{3 - \beta + 2\lambda + 2\beta \lambda - \lambda ^{2} - \beta \lambda ^{2} }}} \right)} > 0\) for any 0 < β < 1 and 0 < λ < 1, where ψ 3 = 3 + β + (1 – β)(2 − λ)λ and ψ 4 = 11 – 6β −β 2 + (1 + β)(5 + β)(2 − λ)λ. (2) Effort maintenance: \(e^{ * }_{1} {\left( C \right)} - e^{ * }_{1} {\left( I \right)} = \frac{{{\left( {1 - \lambda } \right)}{\left( {5 + 2\beta + \beta ^{2} + {\left( {1 - \beta } \right)}{\left( {3 + \beta } \right)}{\left( {2 - \lambda } \right)}\lambda } \right)}}}{{\psi _{3} \psi _{4} }} - \frac{{1 - \lambda }}{{2{\left( {3 - \beta + 2\lambda + 2\beta \lambda - \lambda ^{2} - \beta \lambda ^{2} } \right)}}}\), and e 1 *(C) − e 1 *(I) has the same sign as F(β, λ) = −3 + 12β − β 2 − 2λ + 2β 2 λ + λ 2−β 2 λ 2. Therefore, e 1 *(C) − e 1 *(I) > 0 if \( \beta > \underset{\raise0.3em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle-}$}}{\beta } {\left( \lambda \right)} \), where \( \underset{\raise0.3em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle-}$}}{\beta } {\left( \lambda \right)} \) is defined by the implicit function \( F{\left( {\underset{\raise0.3em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle-}$}}{\beta } {\left( \lambda \right)},\lambda } \right)} = 0,\,\underset{\raise0.3em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle-}$}}{\beta } {\left( \lambda \right)} \) is bounded between 0.25 and 0.35 and \( \frac{{\partial \underset{\raise0.3em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle-}$}}{\beta } {\left( \lambda \right)}}} {{\partial \lambda }} = - \frac{{ - 2{\left( {1 - \beta ^{2} } \right)}{\left( {1 - \lambda } \right)}}} {{2{\left( {6 - \beta + 2\beta \lambda - \beta \lambda ^{2} } \right)}}} > 0 \). (3) Price premium: \(p^{ * }_{2} {\left( C \right)} - p^{ * }_{1} {\left( C \right)} = \frac{{2{\left( {16 + 2\beta - 2\beta ^{2} + 14\lambda - 4\beta \lambda + 6\beta ^{2} \lambda - 3\lambda ^{2} + 2\beta \lambda ^{2} - 7\beta ^{2} \lambda ^{2} - 4\lambda ^{3} + 4\beta ^{2} \lambda ^{3} + \lambda ^{4} - \beta ^{2} \lambda ^{4} } \right)}}}{{\psi _{3} \psi _{4} }} - \frac{{2{\left[ {14 + 2\beta + {\left( {2 - \lambda } \right)}\lambda {\left( {9 - 2\beta + \beta ^{2} + 2\lambda - 2\beta ^{2} \lambda - \lambda ^{2} + \beta ^{2} \lambda ^{2} } \right)}} \right]}}}{{\psi _{3} \psi _{4} }} > 0\) for any 0 < β < 1 and 0 < λ < 1. (4) Effort premium: \(e^{ * }_{2} {\left( C \right)} - e^{ * }_{1} {\left( C \right)} = \frac{{{\left( {1 - \lambda } \right)}{\left( {7 + 2\beta - \beta ^{2} + {\left( {1 - \beta } \right)}^{2} {\left( {2 - \lambda } \right)}\lambda } \right)}}}{{\psi _{3} \psi _{4} }} - \frac{{{\left( {1 - \lambda } \right)}{\left( {5 + 2\beta + \beta ^{2} + {\left( {1 - \beta } \right)}{\left( {3 + \beta } \right)}{\left( {2 - \lambda } \right)}\lambda } \right)}}}{{\psi _{3} \psi _{4} }} > 0\) for any 0 < β < 1 and 0 < λ < 1. Take first derivative respect to λ, and it can be shown that, when β is sufficiently high, the differences of (1) through (4) all decrease. Therefore, the qualitative findings from the basic model remain unchanged; however, the price/effort premium and maintenance results are weakened. The branding support received by the company store \(a^{ * } {\left( C \right)} = \frac{{2{\left( {1 + \beta } \right)}{\left( {1 - \lambda } \right)}}}{{\psi _{4} }}\), which becomes smaller as λ increases. It can be shown that the profits of channel members all decrease as λ increases.

1.6 Product Assortment

Brand 2 is supplied by another manufacturer M 2. The qualitative findings from the basic model remain unchanged (the lengthy mathematical details are omitted). The profits of competing manufacturer M 2 with co-located company store is \({\prod {^{{M^{ * }_{2} }} } }{\left( C \right)} = \frac{{8{\left( {9 - \beta ^{2} } \right)}{\left( {21 - \beta ^{2} + 18\gamma - 2\beta ^{2} \gamma } \right)}{\left[ {339 + 169\beta + 9\beta ^{2} + 11\beta ^{3} + 10{\left( {3 - \beta } \right)}{\left( {3 + \beta } \right)}^{2} \gamma } \right]}^{2} }}{{{\left( {\psi _{5} + \psi _{6} } \right)}^{2} }}\), where Ψ5 = 46035 + 3888β − 15129β 2 − 3616β 3 + 425β 4 + 240β 5 + 29β 6 and Ψ6 = 4(9 − β 2)γ(1503 + 120β − 402β 2 − 120β 3 − 13β 4 + 243γ − 54β 2 γ + 3β 4 γ).

The profits of competing manufacturer M 2 without co-located company store is \(\prod {^{M_2^ * } \left( I \right)} = \frac{{8\left( {3 - \beta } \right)\left( {21 - \beta ^2 + 18\gamma - 2\beta ^2 \gamma } \right)\left( {129 + 8\beta - 5\beta ^2 + 90\gamma - 10\beta ^2 \gamma } \right)^2 }}{\begin{gathered} \hfill \\ \left( {3 - \beta } \right)\left[ {5787 + 1296\beta - 430\beta ^2 - 80\beta ^3 + 3\beta ^4 + 4\left( {9 - \beta ^2 } \right)\gamma \left( {183 + 40\beta - 3\beta ^2 + 27\gamma - 3\beta ^2 \gamma } \right)^2 } \right] \hfill \\ \end{gathered} }\). \( {\prod {^{{M^{ * }_{2} }} } }{\left( C \right)} - {\prod {^{{M^{ * }_{2} }} } }{\left( I \right)} \) has the same sign as −9 + 246β + 42β 2 − 14β 3 − β 4 + 2(9 − β 2)(3 + 6β + β 2)γ which is greater than zero if β > 0.05. Thus, the competing manufacturer can be benefited from the channel structure with a co-located company store.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Bell, D.R. & Padmanabhan, V. Manufacturer-owned retail stores. Mark Lett 20, 107–124 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-008-9054-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-008-9054-1