Abstract

Different arguments have been introduced in the literature both for and against large and small board sizes. In this context, empirical evidence regarding the impact of board size on corporate performance is less conclusive, which means that further study is needed. Contrary to previous work, it is hypothesized in this study that the relationship between board size and corporate performance is more likely to be confounded by board leadership structure. Econometric analysis provided strong evidence for the applicability of this hypothesis and demonstrated that board size positively affects corporate performance in the presence of CEO non-duality (board leadership structure that is split between the roles of the CEO and the roles of the chairman). Furthermore, board size is shown to have a negative influence on corporate performance in the presence of CEO duality (board leadership structure that assigns the roles of both CEO and chairman to the same person). This conclusion is robust to the use of different measures of corporate performance, control variables and econometric models. Thus, these findings cast doubt on most of the existing evidence that posits that either large or small board size is always the best alternative to be followed in all organizations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Corporate governance structures and mechanisms have so far been the main focus of many managerial and financial studies. The underlying premise of this work is that modern firms need control instruments to converge shareholder value and management interest (Jensen and Meckling 1976). Current literature proposes various mechanisms to attain such convergence, such as incentive financial plans, managerial ownership, takeover threats, board of directors, and other internal and external control systems. In this context, the board of directors, if designed well, is argued to be an important corporate governance mechanism that helps in developing the CEO’s decisions (Monks and Minow 1995; Yermack 1996). This argument has motivated researchers to examine various aspects of the board of directors such as board accountability (e.g., Aguilera 2005; Huse 2005), board size (e.g., Yermack 1996; Raheja 2005; Lehn et al. 2003; Coles et al. 2008), composition (e.g., Dalton et al. 1998; Kiel and Nicholson 2003), and leadership structure (e.g., Boyd 1995; Brickley et al. 1997; Elsayed 2009).

The main aspect of the existing work is that most of the presented evidence has focused on either the Anglo-American context (e.g., Yermack 1996; Huther 1997; Conyon and Peck 1998; Bhagat and Black 2001; Cheng 2008; Coles et al. 2008; Belkhir 2009), or on other developed countries (e.g., Eisenberg et al. 1998; Bohren and Odegaard 2001; Postma et al. 2003; Loderer and Peyer 2002; Beiner et al. 2004; Bennedsen et al. 2004; Bozec and Dia 2007; Di Pietra et al. 2008; Sofia and Vafeas 2009). Thus, the key objective of this paper is to show how certain corporate governance “rules” can be applicable in the Egyptian context as potential evidence regarding other “countries with different legal, institutional, and regulatory systems” is limited (Guest 2008: 52).

In fact, more studies in other contexts are needed for a better understanding of the dynamics of boards of directors. This is a crucial issue for theoretical as well as empirical research, as it may not be valid to generalize conclusions from prior studies on other firms that operate in “different legal and cultural environments” (Eisenberg et al. 1998: 36). Another reason for this is that national institutions may not only facilitate some corporate governance mechanisms while hindering others but may also differentially distribute power within firms (Aguilera 2005).

Prior studies have focused on board size as a corporate governance mechanism and tired to establish a link with various organizational and strategic issues such as CEO compensation (Holthausen and Larcker 1993), strategic change (Goodstein et al. 1994), firm efficiency (Huther 1997), informativeness of annual accounting earnings (Ahmed et al. 2006), and corporate failure (Chaganti et al. 1985). However, the net impact of board size on corporate performance is not yet definite, as prior studies have presented inconclusive evidence regarding this relationship (e.g., Yermack 1996; Eisenberg et al. 1998; Kiel and Nicholson 2003; Bhagat and Black 2001; Bennedsen et al. 2004; Bozec and Dia 2007; Coles et al. 2008; Di Pietra et al. 2008; Kaymak and Bektas 2008; Belkhir 2009; Sofia and Vafeas 2009).

Critical examination of prior studies indicates that the relationship between board size and corporate performance is hypothesized to be a one-to-one relationship. The problem with this assumption is that it ignores the fact that the effectiveness of board of directors as a corporate governance mechanism is more likely to be contingent on some contextual variables, as well as on the power of key internal and external actors (Aguilera and Jackson 2003; Aguilera 2005; Huse 2005). In other words, prior works fail to realize either that various governance “elements may complement each other in a consistent way to form path-dependent national systems within broader institutional and cultural context” (Aguilera et al. 2008: 483) or that the effect of one mechanism can depend upon others (Adams et al. 2003).

In this context, it is argued here that main variable that may confound the relationship between board size and corporate performance is board leadership structure. Board leadership structure refers to whether the firm has one person to execute the duties of the CEO and the chairman (i.e., CEO duality), or whether it assigns these positions to different people (i.e., CEO non-duality). Although board leadership structure varies across countries, many codes of good governance currently encourage firms to separate these two roles (Aguilera and Cuervo-Cazurra 2009). “For example, while the previous UK Cadbury report in 1992 recommends the separation of the role of Chairman and CEO, the revised Combined Code in 2003 requires that CEO should not become Chairman of the same company” (Aguilera and Cuervo-Cazurra 2009: 383). Empirically, previous work has documented a remarkable decline trend in the ratio of CEO duality for large publicly traded firms. For instance, recent US empirical studies showed that CEO duality ratio decreased from 76% in Booth et al. (2002) to 62% in Boone et al. (2007) and reached 58.3% in Linck et al. (2008). This ratio has reached 22% in the UK context, as reported in Lasfer (2006). The only known ratio of the CEO duality in the Egyptian context is around 79%, as documented in Elsayed (2007, 2009).

Discussion of the moderating effect of board leadership structure on the relationship between board size and corporate performance is rare in the existing literature. This omission is surprising, given the wide range of evidence for the importance of the moderating effect of board leadership structure in examining various strategic and organizational issues. Examples of these issues include the relationship between CEO tuner and outsider awareness of CEO decision style (Judge and Dobbins 1995), the association between informativeness of earnings and levels of insider ownership (Gul and Wah 2002), the relationship between outside directors and corporate performance (Desai et al. 2003), the influence of the board chairman on CEO dismissal and replacement (Bresser et al. 2006), the link between a firm’s capability and competitive activity (He and Mahoney 2006), and the association between corporate performance and either board composition (Combs et al. 2007) or CEO compensation (Dorata and Petra 2008).

Board leadership structure may confound the relationship between board size and corporate performance because it may encourage (or discourage) some inner or outer actors to join (or withdraw from) the game (Elsayed 2009). For instance, board leadership structure that does not split the roles of the CEO and the chairman (i.e., CEO duality structure) may impede outside directors from practicing their authority in monitoring management (Lorsch and MacIver 1989). Furthermore, board leadership structure may detract from the effectiveness of the board of directors by reflecting the relative power of the CEO in setting the board’s agenda, controlling information flow, and weakening independency of outside members (Boyd 1995; Brickley et al. 1997; Desai et al. 2003).

Thus, this study is designed to add to existing literature by exploring the moderating effect of board leadership structure through testing the relationship between board size and corporate performance using a sample of Egyptian listed firms. Doing so not only helps to better understand the comparative corporate governance debate, but it also can enhance corporate governance practices in Egypt as an emerging market. Presenting data from other less developed contexts is more likely to develop the existing theory of corporate governance, as countries’ cultural differences will cause directors to have different ethical perceptions and orientations (Aguilera 2005).

The remainder of this research is structured as follows. The second section is devoted to presenting theoretical as well as empirical evidence regarding the relationship between board size and corporate performance and to developing some testable hypotheses. Sample and variable measurements are found in the third section. Empirical findings are presented in the fourth section. The final section is dedicated to portray conclusions, discussion of the main findings, and some directions for future work.

2 Theory and hypothesis development

Researchers in corporate governance have argued that board size is more likely to play a central role as an internal mechanism in lessening conflict of interest between managers, who control corporate resources, and owners, whose equity stakes often do not justify monitoring cost. In this context, the board of directors is argued to have three main functions. It is usually responsible for advising the CEO by providing the needed information to optimize the outcomes of managerial decisions. Moreover, the members of this board are needed to use their established connections with external parties to obtain and access more resources to help the firm in attaining its objectives. The third, and possibly the most important function of the board of directors, is to monitor the decisions of the CEO to ensure that they are in the interest of the shareholders (Johnson et al. 1996; Guest 2008).

Different and opposing theoretical arguments are presented in the literature to support both large and small board sizes. Large board size is argued to benefit corporate performance as a result of enhancing the ability of the firm to establish external links with the environment, securing more rare resources, and bringing more highly qualified counsel (Dalton et al. 1999). In other words, “the greater the need for effective external linkage, the larger the board should be” (Pfeffer and Salancik 1978: 172). Furthermore, large board size may improve the efficiency of the decision-making process as a result of information sharing (Lehn et al. 2003).

On the other hand, advocates of small board size (e.g., Lipton and Lorsch 1992; Jensen 1993; Yermack 1996) argued that when a board becomes large, the ability of the board of directors to satisfy its main functions will be limited. Specifically, as a large group (board size) has less group cohesiveness, it is more likely to experience communication and coordination difficulties, which may increase free-rider problems, information sharing cost, and the possibility of the CEO controlling the board. Furthermore, new ideas and complete opinions are less likely to be expressed in large groups, and the monitoring process becomes more diffuse (Dalton et al. 1999; Ahmed et al. 2006).

Empirical studies that tackled the relationship between board size and corporate performance have yielded mixed and inconclusive evidence. Table 1 presents a summary of the key findings of these studies.

The main conclusion that can be drawn from Table 1 is that, while some authors have provided empirical evidence to support the positive influence of small board size on corporate performance (e.g., Yermack 1996; Huther 1997; Eisenberg et al. 1998; Conyon and Peck 1998; Bohren and Odegaard 2001; Postma et al. 2003; de Andres et al. 2005), other authors have offered supportive evidence for the positive influence of large board size (Dalton et al. 1999; Kiel and Nicholson 2003; Bozec and Dia 2007; Belkhir 2009). Yet other scholars have revealed no relationship between board size and corporate performance (Kaymak and Bektas 2008). On the other hand, some studies have provided evidence that this relationship is more likely to be nonlinear (Bennedsen et al. 2004) and to vary with the used performance measure (Bhagat and Black 2001; Loderer and Peyer 2002), estimate method (Maka and Kusnadi 2005), firm complexity (Coles et al. 2008), firm size and industry type (Di Pietra et al. 2008), and growth of board size (Sofia and Vafeas 2009).

Critical examination of this literature indicates that although there is a tendency for the negative effect of large board size to outweigh the positive, prior studies “fail[ed] to convincingly explain why marginally larger boards should impair performance” (Loderer and Peyer 2002: 182). For instance, in their comments, Hermalin and Weisbach (2003: 13) asked “why, if they are destructive to firm value, do we see large boards? Perhaps large boards are uniformly bad because size exacerbates some free-riding problems among directors vis-à-vis the monitoring of management. But then why does the market permit them to exist—why hasn’t economic Darwinism eliminated this unfit organizational form?’’

In fact, to assume that “one size fits all” and argue that a “large/small board size” is always the right choice is to make an idealistic argument. The problem of this assumption is that it ignores the fact that the effectiveness of the board of directors as a corporate governance mechanism is more likely to be contingent on some contextual variables, as well as on the power of key internal and external actors (Aguilera and Jackson 2003; Aguilera 2005; Huse 2005). Put another way, prior work fails to notice either that “various governance elements may complement each other in a consistent way to form path-dependent national systems within broader institutional and cultural context” (Aguilera et al. 2008: 19) or that the effect of one mechanism can depend upon others (Adams et al. 2003).

A more balanced view posits that business organizations often design their corporate governance systems to minimize their total cost, as one weak governance mechanism in one area will be offset by a strong one in another area (Donnelly and Kelly 2005). Thus, the optimal combination of governance mechanisms is more likely to vary with firms as the related costs and benefits differ across firm characteristics (Ahmed and Duellman 2007), industries (Huse 2005), and countries (Ahmed et al. 2006). This indicates that “there is not one best design of corporate governance, but various designs are not equally good” (Huse 2005: S67). This argument is more likely to be acceptable, as “path-dependency legacies and national institutional settings” (Aguilera 2005: S41) are considered to be important factors in understanding how corporate governance models are changing around the world.

The absence of conclusive evidence regarding the net impact of board size on corporate performance, as explained above, needs researchers to think differently about the issue. One possible explanation for these mixed findings is that it may not be board size per se that influences the firm performance. Rather, the relationship between board characteristics (such as board size and board leadership structure) and corporate performance is more likely to be a non-monotonic one that may vary with the interaction between these characteristics. Unfortunately, “[r]esearch so far has focused almost exclusively on the board of directors and ignored the potential interaction effect of other control devices. However, because different corporate governance methods may substitute for or complement each other, the results of the impact of any one mechanism could potentially be biased” (Bozec and Dia 2007: 1735).

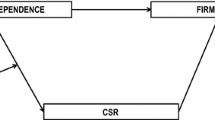

This observation suggests that the main hypothesis in this paper can be stated as follows: to minimize the total agency cost, the firm will seek to manipulate between designs of board size and board leadership structure. In other words, board leadership structure is more likely to moderate the relationship between board size and corporate performance, as shown in Fig. 1.

According to Fig. 1, if the firm has a large board size and at the same time decides to follow a CEO duality structure, then this decision is more likely to detract from its financial performance. This is because CEO duality may detract from the effectiveness of the board of directors by reflecting the relative power of the CEO in setting the board’s agenda, controlling information flow, and weakening the independency of outside members (Boyd 1995; Brickley et al. 1997; Desai et al. 2003) as follows: First, a large board size is more likely to enable the CEO to dominate the board of directors as a result of group diffusion. That is, there is a high chance of managerial entrenchment as a result of the weak monitoring role of the board of directors. Second, information asymmetry between the executive manager and the board of directors is expected to increase with CEO duality (Eisenhardt 1989). This is because the executive manager under the CEO duality leadership structure possesses complete information about the day-to-day work and industry context, which often is not available to the boardroom (Elsayed 2009). Asymmetric information will contribute to communication and coordination problems that characterize large groups to weaken the monitoring power of the board of directors. This, in fact, may explain why most of the USA studies (where CEO duality structure and large board size are the main characteristics—Review Table 1) reported a negative relationship between board size and corporate performance. Third, board leadership structure may encourage (or discourage) some inner or outer actors to join (or withdraw from) the game (Elsayed 2009). For instance, CEO duality leadership structure may impede outside directors from practicing their authority in monitoring the management (Lorsch and MacIver 1989). Therefore, the first hypothesis in this paper can be stated as follows:

H1

Board size is more likely to affect corporate performance negatively under the board leadership structure that combines the roles of the CEO and the chairman.

On the other hand, a large board of directors may “serve as an additional conduit that enhances the firm’s capability because directors themselves possess valuable social and human capital that can be deployed by the firm to engage in competitive actions” (He and Mahoney 2006: 4). Thus, if we agree that “individual governance provisions can complement or substitute for one another in containing agency conflicts” (Faleye 2007: 244) and that the rational firm will manipulate its board characteristics to attain the minimum total cost, then the firm is more likely to separate the roles of the CEO and the chairman (CEO non-duality) to compensate for the agency of large board size. If this is the case, a positive association between board size and corporate performance is expected. This is because benefits of CEO-non duality (such as decreasing agency cost, separating decision-management from decision-control, increasing decision efficiency as a result of more discussion, and reducing managerial entrenchment) are expected to outweigh the costs of large board size. This argument is consistent with some observations in the previous work that acknowledge that “the decision to separate the roles [of the CEO and Chairman] appears to be positively related to the size of the firm’s board” (Dedman 2002: 340), and firms with CEO non-duality leadership structure have larger board size than firms with CEO duality leadership structure (Faleye 2007; Elsayed 2009). Therefore, the second hypothesis in this paper can be stated as follows:

H2

Board size is more likely to affect corporate performance positively under the board leadership structure that separates the roles of the CEO and the chairman.

3 Sample description and variable measurement

3.1 Sample selection

The sample in this study was selected from Egyptian companies that were listed during the period from 2000 to 2004. This period was mainly chosen because during this time, Egypt began to identify corporate governance as a necessity for settling its economic reform program (Abdel 2001; Fawzy 2003). In addition, it covers ex- and post-effects of the initiation of new listing rules in the Egyptian stock market in 2002. In addition, much of the existing evidence regarding corporate governance mechanisms in Egypt covers most of this period (see, for example, Abdel 2001; Fawzy 2003; MENA 2003; ROSC 2004; MENA–OECD 2006; Elsayed 2007), aiding comparisons of the results of this study.

The number of listed firms in the CASE dropped from 1,076 firms with a total market capitalization of LE 121 billion in 2000 to 795 firms with a total market capitalization of LE 234 billion in 2004 (Cairo and Alexandria Stock Exchange 2007). As tax laws encourage listing, “few active companies constitute the bulk of trading over the Egyptian Exchange” (Abdel 2001: 10). The sample searching began by examining lists of the most active firms published by CASE during 2000–2004. This study excluded from these lists firms that belonged to financial industries, as these companies are subject to unique governmental regulations and their operations are quite different. The needed data on board structure and explanatory variables were found to be available for 92 firms covering 19 different industrial sectors.

Abdel (2001), for example, utilized a list of the 90 most active firms in the Egyptian stock market and observed that they accounted for 87% of the total deals and 44% of the total market capitalization in 2000. Following that and to test for whether the sample of the current study represents all listed firms in the CASE, the average of the total market capitalization during 2000–2004 for all companies listed in the CASE, as well as for those firms constituting the sample, is computed. The average for all listed firms was LE 537.4 billion and reached LE 246.91 billion for the sample. Given that the sample accounted for 46% of the total market capitalization of the entire market during 2000–2004, it can be argued that sample does represent the population (i.e., all firms listed in the CASE).

3.2 Dependent variable

Corporate performance is the main dependent variable. There is extensive literature on the appropriate measurement of performance, which has led to little consensus on the best approach. In estimating the effects of board size, Bhagat and Black (2001) referred to the importance of using different measures of corporate performance as a plausible way to yield robust results. For this reason, three alternative measures of corporate performance were considered in this study: Tobin’s q, return on assets, and return on equity.

Martin (1993) pointed out that “q and profitability measures should be regarded as complements rather than substitutes. Both contain information about market power, and there is no compelling reason to think that either type of measure dominates the other” (p. 516). Tobin’s q (Q) is the ratio of the firm market value to the replacement cost of its assets (Lindenberg and Ross 1981). In an equilibrium situation, the Tobin’s q ratio has a value of unity. Investment is stimulated if the ratio is greater than one. On the other hand, if it is below one, this indicates a low incentive to invest (Kim et al. 1993). Tobin’s q ratio is measured using Chung and Pruitt’s (1994) simple approximation, presented by Lee and Tompkins (1999) as follows:

where MV (CS) is the market value of the common stocks; BV, the book value; PS, the preferred stocks; LTD, the firm long-term debt; INV, the inventory; CL, the current liabilities; CA, the current assets, and TA, the total assets.

The other two profitability-based measures of firm performance are return on assets (ROA) and return on equity (ROE), each of which is computed by dividing firm profits before taxes by its total assets and total equity, respectively.

3.3 Independent variable

Board size is the main dependent variable in this study. The Egyptian legal system specifies that the board of directors for any company should be not only constituted according to capital distribution but also nominated to represent shareholders. “Egyptian companies have single tier boards comprised of an odd number of members, with a minimum of three” (ROSC 2004: 12). Board size is exemplified by the total number of directors on the board (Wen et al. 2002; Kim 2005). The natural logarithm is used to transform the number of directors because it does not follow the normal distribution (the Shapiro–Wilk W test for normality is significant at 0.968, p < 0.05). In fact, some authors (such as Lipton and Lorsch 1992; Jensen 1993) have argued that boards of directors that include more than seven members are more likely to be inefficient and that a negative impact of board size on corporate financial performance is more likely to be detected. Thus, to test for this argument and check for the robustness of the findings that are reported in this paper, another dummy variable is generated to express board size. This dummy variable takes the value of one if board size is more than seven and zero otherwise.

3.4 Moderating variable

The Egyptian legal system does not prohibit CEO duality, and “in most listed companies, there is no separation between the role of the chairman and managing director roles. The same person may hold both posts” (Abdel 2001, p. 55). A binary variable is used as a proxy for board leadership structure. This binary variable takes a value of one if it is found that the CEO also serves as the chairman (i.e., CEO duality), and a value of zero otherwise.

3.5 Covariate variables

A number of associated control variables, according to previous work, were included in the analysis models. The firm’s total assets provide a proxy for the firm size (Eisenberg et al. 1998). The natural logarithm is employed to transform firm size, as the Shapiro–Wilk W test for normality is significant (0.332, p < 0.001). Firm leverage is measured by the ratio of total debt to total assets (Baliga et al. 1996). Capital intensity is utilized to express firm growth and is measured by the ratio of net fixed assets to total assets (Elsayed and Paton 2009). Firm age is represented by the time period from the incorporation date to the year of analysis (Eisenberg et al. 1998; Mumford 2003).

Additionally, analysis models also control for firm ownership structure, as many companies are owned by family groups or individuals. In contrast to the USA/UK, where the level of individual share ownership has decreased and the proportion of institutional investors has increased (Mallin 2002), many Egyptian companies are held by relatively few shareholders due to tax laws that encourage listing (ROSC 2004). Moreover, the Egyptian market is dominated by retail investors, who account for 50–60% of the total equity in the market, for which foreign investment and domestic institutional investors are relatively small (Abdel 2003; ROSC 2004). Domestic banks are the dominant institutional investors in Egypt (see, for example, Wels 2007), and institutional investors have no active role in practicing their voting rights (ROSC 2004). Thus, ownership structure is divided into managerial shareholding, institutional ownership, employee ownership, private shareholding, and foreign shareholding. Each variable is represented based on the proportion of its stake to the total equity, respectively.

Furthermore, since the relationship between board characteristics and corporate performance is more likely to vary across industries (Elsayed 2007), industry heterogeneity is also controlled for. Industry effect is captured by inclusion of dummy variables using the two-digit standard industrial classification codes. Descriptive statistics of the variables explained above are presented in Table 2.

4 Empirical analysis

4.1 Descriptive statistics and preliminary analysis

Descriptive statistics, as reported in Table 2, indicate that the average (median) board size is 8 (7). Thus, board size is, to some extent, close to the figures reported in both US and UK studies. For instance, Linck et al. (2008) reported an average (median) of 7.5 (7) in the US context. Guest (2008) reported an average (median) of 7.18 (7) using the UK dataset. Furthermore, classification of firms according to their board leadership structure (i.e., CEO duality or CEO non-duality) showed that the same person holds the posts of CEO and chairman (i.e., CEO duality) in about 79% of the sample. Further analysis, which is not shown in Table 2, indicated that while the average board size in the CEO duality group is 7.78 members with a standard deviation of 2.83 members, it is 8.55 members with a standard deviation of 3.02 in the CEO non-duality group. A T-test was conducted to explore whether board size varies with board leadership structure. The result demonstrated that there is a significant difference in board size (T = 2.09, p = 0.037) between firms that apply CEO duality structure and those firms that follow CEO non-duality structure. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed that the average value of board size also varies across industries as the F-statistic = 10.26, p < 0.001.

4.2 Testing for expected endogeneity

Hermalin and Weisbach (2003) argued that very few empirical works on corporate governance have considered the issue of endogeneity between firm performance and board characteristics. It is important to note that their conclusion was based purely on a review of the economic literature, and relevant managerial studies were omitted (see their work, p. 8). However, in the spirit of their argument, estimating individually either corporate performance or board size, the existence of an endogeneity effect would lead to biased and inconsistent estimates as a result of the expected correlation between the error term and the endogenous variable. Therefore, the Hausman (1978) specification test for endogeneity is preformed as illustrated in Gujarati (2003). The F-test for the predicted value of board size was not significant. Specifically, using Tobin’s q as a proxy for corporate performance, F = 0.571 (p = 0.450), with ROA as a proxy for corporate performance, F = 0.380 (p = 0.536), and with ROE as a proxy for corporate performance, F = 0.210 (p = 0.645). These findings indicate that there are no signs for potential endogeneity between board size and corporate performance.

4.3 OLS regression

To be able to test the main hypotheses in this study, OLS regression models were established, in which, firm performance (expressed by Tobin’s q, ROA, and ROE) is the main dependent variable, and board size (expressed by either log of board size or a dummy variable to refer to board size if it is >7) is the main independent variable, also controlling for the other variables, as explained above. Specification tests of the OLS assumptions (reported in Table 3) confirm that homoscedasticity and normality of residuals, as two main assumptions of OLS, are both violated. Running the interquartile range test (Hamilton 2003) suggests that this can be traced back to the presence of severe outliers. This is because the Breusch-Pagan/Cook-Weisberg test for heteroskedasticity and the Shapiro–Wilk W test for normality of residuals in all cases are significant (p < 0.001).

4.4 Robust regression

With the existence of heteroskedasticity, OLS is still linear and unbiased but is no longer efficient (Gujarati 2003). Furthermore, Dielman and Rose (1997) suggest that “estimating regression models using ordinary least squares (OLS) yields parameter estimates that are unbiased and have minimum variance when the disturbances are independent and identically normally distributed. In the presence of non-normal errors, however, the performance of OLS can be quite impaired, especially if the errors follow a distribution that tends to produce outliers” (p. 239). One possible way to correct for heteroskedasticity is to use a robust regression model (Rousseeuw and Leroy 2003). Alternatives that are available to correct for non-normality of residuals include transforming variables to achieve normal distributions or using discriminant analysis (Tabachnick and Fidell 2001). However, as it is less affected by outliers, median regression “has recently gained acceptance as an alternative to ordinary least squares (OLS) estimation when outliers may be present” (Dielman and Rose 1995: 199).

Therefore, STATA version 8 was used to perform robust regression (using iteratively reweighted least squares) and median regression. Table 4 presents the results of robust regression and median regression using Tobin’s q as a proxy for corporate performance (where board size is represented by either the log of board size or a dummy variable that takes the value of one if board size > 7 and zero otherwise). The results give quite supportive evidence for the applicability of the main hypotheses in this study. Particularly, by using the log of board size as an explanatory variable, results of robust regression (Model 2—coefficient 0.086, p < 0.05) and results of median regression (Model 4—coefficient 0.165, p < 0.01) indicate that board size has a positive impact on Tobin’s q ratio when the firm applies the CEO non-duality structure. However, board size has exerted a negative and significant coefficient on Tobin’s q ratio under robust regression (Model 2—coefficient −0.099, p < 0.01) and median regression (Model 4—coefficient −0.176, p < 0.01) when the firm follows the CEO duality structure. These findings are also supported when the dummy variable of board size (board size > 7) is used as an independent variable (see Model 6 and Model 8 in Table 4).

Further analysis was performed by running the Wald test to test for the null hypothesis that CEO duality group and CEO non-duality group have equal parameters for the effect of board size on corporate performance. According to the results reported in Table 4, the null hypothesis can be rejected, as the F-statistic is significant under all models. This finding gives a substantial reassurance regarding the applicability of the main hypotheses in this study; the impact of board size on corporate performance varies with board leadership structure.

Robust regression and median regression were also conducted using ROA as a proxy for corporate performance, and results are shown in Table 5.

Once again, as shown in Table 5, when interaction terms between board size and board leadership structure (i.e., CEO duality) are included in regression models, board size is shown to exert positive and significant coefficients on ROA if the firm follows a leadership structure that separates the roles of CEO and chairman (i.e., CEO non-duality). These coefficients are as follows: in Model 2 (5.83, p < 0.01), Model 4 (4.22, p < 0.05), Model 6 (4.93, p < 0.001), and Model 8 (4.30, p < 0.001). On the other hand, board size (log of board size and board size > 7) was found to exert negative coefficients on ROA when the CEO also has the position of the chairman (i.e., in the CEO duality scenario). Specifically, coefficients of board size on ROA are as follows: in Model 2 (−5.41, p < 0.01), Model 4 (−4.25, p < 0.05), Model 6 (−5.16, p < 0.001), and Model 8 (−5.94, p < 0.001). Significant results of Wald tests in all models, as reported in Table 5, indicate that the effect of board size on ROA varies with board leadership structure. The results of using ROE, as reported in Table 6, give quite similar findings to those of using either Tobin’s q or ROA.

Although empirical findings referred to the significance of most of control variables, the results did not demonstrate a clear pattern, as it seems that the relationships between these variables and firm performance vary with the proxy used for corporate performance. Managerial ownership is the only control variable that did not show any significant relationship with corporate financial performance under any case. However, the validity of the industry effect as an important control variable was supported in all cases. The joint F-test for industry effect is significant under any model reported in Tables 4, 5, and 6. This indicates that corporate performance varies with industry type.

5 Robustness test

To check for the rigor of the main findings presented above, factor analysis was explored to construct a factor using all three measures of corporate financial performance (i.e., Tobin’s q, ROA, and ROE). Principal component analysis with Varimax as a common orthogonal rotation method was used on the standardized forms of the three variables (Tabachnick and Fidell 2001). The Kaiser criterion that retains factors with eigenvalues greater than or equal to unity was employed to determine the number of factors. Next, the values of the Kaiser–Meyer–Oklin (KMO) and Bartlett’s sphericity statistics were checked to test for the factorability of the data (i.e., testing the null hypothesis that states that the correlation matrix is an identity matrix; Hair et al. 1998).

Based on the Kaiser criterion, one factor has been extracted (which has an eigenvalue of 1.219) to express corporate financial performance. The factorability of the data is assured, as the Kaiser–Meyer–Oklin (KMO) statistic is not less than 0.6 and the Bartlett’s test of Sphericity is significant (Chi-square 14.687, p = 0.002). Thus, the hypothesis that the correlation matrix is an identity matrix can be rejected (Tabachnick and Fidell 2001; Pallant 2001), and the output factor is valid.

The resulted factor that expresses corporate financial performance was used as a dependent variable to examine the effect of board size (using both measures of board size: log of board size and board size > 7), and Table 7 displays the results of running robust regression as well as median regression. The validity of the main hypotheses in this study is once again assured, as it can be seen in Table 7 that while board size affects corporate performance positively in the presence of CEO non-duality, it has a negative influence on corporate performance in the presence of CEO duality.

6 Conclusion and discussion

Board characteristics have been the subject of many recent studies with different theoretical perspectives. Unfortunately, testing the impact of these characteristics on corporate performance displays very mixed findings. In fact, these alternative perspectives have been unable to explain these conflicting results, as they assume that one model can be applied in various contexts. Furthermore, in exploring the link between board characteristics and corporate performance, these theoretical perspectives did not pay enough attention to the interrelationships between board characteristics.

In this context, testing the relationship between board size as one corporate governance mechanism, which can be utilized to mitigate agency costs, and corporate performance showed mixed and inconclusive findings. In contrast to previous work, it has been hypothesized in this study that the relationship between board size and corporate performance is more likely to be moderated by board leadership structure.

Econometric analysis using a sample of Egyptian listed firms provided strong evidence for the applicability of this hypothesis and demonstrated that board size positively affects corporate performance in the presence of CEO non-duality (board leadership structure that splits the roles of the CEO and the chairman). Furthermore, board size is shown to have a negative influence on corporate performance in the presence of CEO duality (board leadership structure that assigns both the roles of CEO and chairman to the same person). This conclusion is robust to the use of different measures of corporate performance, control variables, and econometric models. Thus, these findings cast doubt on most of the existing evidence that posits that either large or small board size is always the best alternative to be followed in all organizations.

One more interesting finding that deserves some discussion is the neutral effect of managerial ownership on corporate performance in all evaluated cases. In fact, establishing a link between managerial ownership and the results that are reported here is a crucial matter, as board size, board leadership structure and managerial ownership can be considered as substitutive corporate governance mechanisms. The net influence of managerial ownership on board structure and composition is not a simple matter. Rather, this effect is more likely to vary not only with country and industry settings but also with the cost, effectiveness, and availability of other corporate governance mechanisms. For instance, in contexts such as Egypt, where family-owned firms are common and a less effective role is taken by institutional investors, the majority of firms tend to adopt the CEO duality structure (Abdel 2001; Fawzy 2003; Elsayed 2007). This is more likely to happen as a consequence of the entrepreneur’s domination: “[i]t is not easy to convince an owner of a company who invested money to step aside and allow others to manage his money” (MENA 2003, p. 37). If this is the case, then managers may increase their ownership stakes in order to boost their voting power, implement decisions that optimize their own interests, and weaken the monitoring power of the board of directors (Fama and Jensen 1983; Lasfer 2006; Lasfer and Faccio 1999; Zheka 2005).

Consequently, the neutral effect of managerial ownership on corporate performance may be driven by the fact that the sample covers different combinations of board structure and composition. For example, a positive effect of managerial ownership in one combination may be balanced out by a negative effect in another. Thus, to explore this point, interaction terms between managerial ownership and board size, as well as board leadership structure, are included in the model that estimates corporate performance using Robust and Median regressions (results are reported in Table 8). Although the main findings of this study are still valid, the interaction term between the board’s characteristics (CEO duality and size) and managerial ownership exerts a negative and significant coefficient on corporate performance (Robust regression: −0.022, p < 0.001, Median regression: −0.034, p < 0.001). At the same time, the interaction term between managerial ownership and either CEO duality or board size exerts a positive and significant coefficient. These results imply that managerial ownership may play an important role in evaluating board characteristics and performance.

Since the Egyptian perspective in corporate governance system can best be described as a “combination” structure of the UK voluntary reform and USA mandatory reform, the findings of this study may add to the comparative corporate governance debate in different ways. First, learning that board size only influences corporate performance with the inclusion of board leadership structure provides supporting evidence for the results of previous work that demonstrated that the effect of board size is non-monotonic, varying, for example, with firm complexity (Coles et al. 2008), industry type and firm size (Di Pietra et al. 2008), and growth of the board itself (Sofia and Vafeas 2009). That is, the results of this paper can be positioned in line with previous work that argued that the success of board of directors as a corporate governance mechanism depends on various contextual variables, as well as on the power of key internal and external actors (Aguilera and Jackson 2003; Aguilera 2005; Huse 2005). Furthermore, the net influence of one corporate governance mechanism is more likely to be contingent on the other applied governance mechanisms (Adams et al. 2003). Therefore, a less effective governance mechanism in one area will be counterbalanced by an effective mechanism in another area to minimize the firm’s total agency costs (Donnelly and Kelly 2005).

Second, academic researchers as well as practicing managers need to broaden their insight to understand that board characteristics (e.g., size, leadership structure, and composition) are multidimensional, contingent, and dynamic in their nature and differ across countries, industries, and firms. Therefore, if they want to maximize the added value of these characteristics, they need to know that they cannot talk about these characteristics in a vacuum (i.e., outside of other organizational and environmental variables). Researchers and practitioners must also give more attention to the interrelationship that may exist among board characteristics and to how the influence of one of these characteristics may depend on the other characteristics. In general, these two main points must also be understood by policy makers. In other words, before developing and launching new and additional corporate governance reforms, policy makers should understand that “context” and “actors” will best explain differences in corporate governance systems. This implies that the proponents of small boards and of those large boards may each be under certain conditions. Thus, existing theories might need to be treated as complementary viewpoints, each of which draws upon a part of the whole picture, as depending on just one single perspective is more likely to result in misleading conclusions about the structure as a whole.

Third, comparative corporate governance research must also examine the dynamic of the “virtuous cycle” between corporate governance structure and country institutional characteristics. In other words, “the need for good governance increases as the number of public firms grows because agency problems between disperse owners and managers, or between majority and minority shareholders emerge” (Aguilera and Cuervo-Cazurra 2009: 379). Moreover, strong corporate governance practices and systems at the country level not only promote economic growth for local companies but also attract more foreign investors (Aguilera and Cuervo-Cazurra 2004). More foreign investment, especially for developing countries, means more advanced technology and a greater likelihood of more developed practices (Elsayed 2009).

The findings of this study suggest some directions for future research. First, to confirm the results of this study, researchers are invited to replicate and retest the argument that is presented here in other institutional environments. Second, future research may also examine the role of board composition in the relationship between board size and corporate performance. Third, investigating the interrelationships that exist among board characteristics along the firm life cycle and how these interrelationships may vary with firm lifecycle stages is also a promising future area for researchers. Finally, a remarkable void in the literature is that very few studies have controlled for firm heterogeneity or considered dynamic effects in the relationship between board characteristics and performance. More generally, the majority of previous studies, including the present one, have relied on cross-sectional or pooled data sets. Therefore, future studies are also invited to rely more on panel data techniques, as such techniques allow researchers to control for unobservable firm-specific effects and, as a consequence, have the potential to provide a much more powerful evidence base.

References

Abdel, S. S. (2001). Corporate governance is becoming a global pursuit: What could be done in Egypt? Working paper, working paper (SSRN: social science research network). doi:10.2139/ssrn.286875.

Abdel, S. S. (2003). Does ownership structure affect firm value? Evidence from the Egyptian stock market. Working paper, working paper (SSRN: social science research network). doi:10.2139/ssrn.378580.

Adams, M., Hardwick, P., & Zou, H. (2003). Corporate governance and cost efficiency in the United Kingdom life insurance industry. Working paper, School of Business and Economics, Swansea University.

Aguilera, R. (2005). Corporate governance and director accountability: An institutional comparative perspective. British Journal of Management, 16, S39–S54.

Aguilera, R., & Cuervo-Cazurra, A. (2004). Codes of good governance worldwide: What is the trigger? Organization Studies, 25, 417–446.

Aguilera, R., & Cuervo-Cazurra, A. (2009). Codes of good governance. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 17, 376–387.

Aguilera, R., & Jackson, G. (2003). The cross-national diversity of corporate governance: Dimensions and determinants. Academy of Management Review, 28, 447–465.

Aguilera, R., Filatotchev, I., Gospel, H., & Jackson, G. (2008). An organizational approach to comparative corporate governance: Costs, contingencies and complementarities. Organization Science, 19, 475–492.

Ahmed, A., & Duellman, S. (2007). Accounting conservatism and board of director characteristics: An empirical analysis. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 43, 411–437.

Ahmed, K., Hossain, M., & Adams, M. (2006). The effects of board composition and board size on the informativeness of annual accounting earnings. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 14, 418–431.

Baliga, B., Moyer, C., & Rao, R. (1996). CEO duality and firm performance: What’s the fuss? Strategic Management Journal, 17, 41–53.

Beiner, S., Drobetz, W., Schmid, F., & Zimmermann, H. (2004). Is board size an independent corporate governance mechanism? KyKlos, 57, 327–356.

Belkhir, M. (2009). Board of directors’ size and performance in the banking Industry. International Journal of Managerial Finance (forthcoming).

Bennedsen, M., Kongsted, H., & Nielsen, K. (2004). Board size effects in closely held corporations. Institute of Economics, University of Copenhagen. Working papers, Centre for Applied Microeconometrics (http://www.econ.ku.dk/CAM/).

Bhagat, S., & Black, B. (2001). The non-correlation between board independence and long term firm performance. Journal of Corporation Law, 27, 231–274.

Bohren, O., & Odegaard, B. (2001). Corporate governance and economic performance: A closer look. Working paper, The Norwegian School of Management.

Boone, A., Field, L., Karpoff, J., & Raheja, C. (2007). The determinants of corporate board size and composition: An empirical analysis. Journal of Financial Economics, 85, 66–101.

Booth, R., Cornett, M., & Tehranian, H. (2002). Boards of directors, ownership and regulation. Journal of Banking & Finance, 26, 1976–1996.

Boyd, B. (1995). CEO duality and firm performance: A contingency model. Strategic Management Journal, 16, 301–312.

Bozec, R., & Dia, M. (2007). Board structure and firm technical efficiency: Evidence from Canadian state-owned enterprises. European Journal of Operations Research, 177, 1734–1750.

Bresser, R., Thiele, R., Biedermann, A., & Lüdeke, H. (2006). Opportunist or steward? The influence of the board chairman on CEO dismissals and replacements. Papers presented at the 26th annual conference of the strategic management society, Vienna.

Brickley, J., Coles, J., & Jarrell, G. (1997). Leadership structure: Separating the CEO and chairman of the board. Journal of Corporate Finance, 3, 189–220.

Cairo and Alexandria Stock Exchange (2007). Market data: Main market indicators. (www.egyptse.com) (Access: 12 Nov 2007).

Chaganti, S., Mahajan, V., & Sharma, S. (1985). Corporate board size, composition and corporate failure in retailing industry. Journal of Management Studies, 22, 400–417.

Cheng, S. (2008). Board size and the variability of corporate performance. Journal of Financial Economics, 87, 157–176.

Chung, H., & Pruitt, W. (1994). A simple approximation of Tobin’s q. Financial Management, 23, 70–74.

Coles, J., Daniel, N., & Naveen, L. (2008). Boards: Does one size fit all? Journal of Financial Economics, 87, 329–356.

Combs, J., Ketchen, D., Perryman, A., & Donahue, M. (2007). The moderating effect of CEO power on the board composition—firm performance relationship. Journal of Management Studies, 44, 1299–1323.

Conyon, J., & Peck, I. (1998). Board size and corporate performance: Evidence from European countries. The European Journal of Finance, 4, 291–304.

Dalton, D., Daily, C., Ellstrand, A., & Johnson, J. (1998). Meta-analytical reviews of board composition, leadership structure, and financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 19, 269–290.

Dalton, D., Daily, C., Johnson, J., & Ellstrand, A. (1999). Number of directors and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Academy of Management Journal, 42, 674–686.

De Andres, P., Azofra, V., & Lopez, F. (2005). Corporate boards in OECD countries: Size, effectiveness, functioning and effectiveness. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 13, 197–209.

Dedman, E. (2002). The Cadbury committee recommendations on corporate governance—A review of compliance and performance impacts. International Journal of Management Reviews, 4, 335–352.

Desai, A., Kroll, M., & Wright, P. (2003). CEO duality, board monitoring, and acquisition performance: A test of competing theories. Journal of Business Strategy, 20, 37–56.

Di Pietra, R., Grambovas, C., Raonic, V., & Riccaboni, A. (2008). The effects of board size and ‘busy’ directors on the market value of Italian companies. Journal of Management and Governance, 12, 73–91.

Dielman, T., & Rose, E. (1995). A bootstrap approach to hypothesis testing in least absolute value regression. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 20, 119–130.

Dielman, T., & Rose, E. (1997). Estimating and testing in least absolute value regression with serially correlated distribution. Annals of Operations Research, 74, 239–257.

Donnelly, R., & Kelly, P. (2005). Ownership and board structures in Irish PLCs. European Management Journal, 23, 730–740.

Dorata, N., & Petra, S. (2008). CEO duality and compensation in the market for corporate control. Managerial Finance, 34, 342–353.

Eisenberg, T., Sundgren, S., & Wells, M. (1998). Larger board size and decreasing firm value in small firms. Journal of Financial Economics, 48, 35–54.

Eisenhardt, M. (1989). Making fast strategic decisions in high-velocity environments. Academy of Management Journal, 32, 543–576.

Elsayed, K. (2007). Does CEO duality really affect corporate performance? Corporate Governance: An International Review, 15, 1203–1214.

Elsayed, K. (2009). A multi-theory perspective of board leadership structure: What does the Egyptian corporate governance context tell us? British Management Journal (forthcoming).

Elsayed, K., & Paton, D. (2009). The impact of financial performance on environmental policy: Does firm life cycle matter? Business Strategy and the Environment (forthcoming). doi: 10.1002/bse.608.

Faleye, O. (2007). Does one hat fit all? The case of corporate leadership structure. Journal of Management and Governance, 11, 239–259.

Fama, E., & Jensen, C. (1983). Separation of ownership and control. Journal of Law Economics, 26, 301–325.

Fawzy, S. (2003). Assessment of corporate governance in Egypt, Working paper no 82, the Egyptian Center for Economic Studies.

Goodstein, J., Gautam, K., & Boeker, W. (1994). The effects of board size and diversity on strategic change. Strategic Management Journal, 15, 241–250.

Greene, W. (2003). Econometric analysis (5th ed.). New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Guest, P. (2008). The determinants of board size and composition: Evidence from the UK. Journal of Corporate Finance, 14, 51–72.

Gujarati, D. (2003). Basic econometrics (4th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Gul, F., & Wah, L. (2002). Insider entrenchment, board leadership structure and informativeness of earnings. Working paper, City University of Hong Kong.

Hair, J., Anderson, R., Tatham, R., & Black, W. (1998). Multivariate data analysis. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Hamilton, L. (2003). Statistics with STATA. Belmont, CA: Duxbury/Thomson Learning.

Hausman, A. (1978). Specification tests in econometrics. Econometrica, 46, 1251–1271.

He, J., & Mahoney, J. (2006). Firm capability, corporate governance, and firm competitive behavior: A multi-theoretic framework. Working paper, College of Business, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Hermalin, B., & Weisbach, M. (2003). Boards of directors as an endogenously determined institution: A survey of the economic literature. Economic Policy Review, 9, 7–26.

Holthausen, W., & Larcker, F. (1993). Boards of directors, ownership structure and CEO compensation. Working paper, Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania.

Huse, M. (2005). Accountability and creating accountability: A framework for exploring behavioural perspectives of corporate governance. British Journal of Management, 16, S65–S79.

Huther, J. (1997). An empirical test of the effect of board size on firm efficiency. Economics Letters, 54, 259–264.

Jensen, M. (1993). The modern industrial revolution, exit, and the failure of internal control systems. The Journal of Finance, 48, 831–880.

Jensen, M., & Meckling, W. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behaviour, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3, 305–360.

Johnson, J., Daily, L., & Ellstrand, A. (1996). Board of directors: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 22, 409–438.

Judge, Q., & Dobbins, G. (1995). Antecedents and effects of outside directors’ awareness of CEO decision style. Journal of Management, 21, 43–64.

Kaymak, T., & Bektas, E. (2008). East meets west? Board characteristics in an emerging market: Evidence from Turkish banks. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 16, 550–561.

Kiel, G., & Nicholson, G. (2003). Board composition and corporate performance: How the Australian experience informs contrasting theories of corporate governance. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 11, 189–205.

Kim, Y. (2005). Board network characteristics and firm performance in Korea. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 13, 800–808.

Kim, K., Henderson, G., & Garrison, S. (1993). Examination of Tobin’s q for takeover firms. Quarterly Journal of Business and Economics, 32, 3–26.

Lasfer, M. (2006). The interrelationship between managerial ownership and board structure. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 33, 1006–1033.

Lasfer, M., & Faccio, M. (1999). Managerial ownership, board structure and firm value: The UK evidence. Working paper (SSRN: social science research network). doi:10.2139/ssrn.179008.

Lee, D., & Tompkins, J. (1999). A modified version of the Lewellen and Badrinath measure of Tobin’s q. Financial Management, 28, 20–31.

Lehn, K., Sukesh, P., & Zhao, M. (2003). Determinants of the size and structure of corporate boards: 1935–2000. Working paper, Katz Graduate School of Business.

Linck, J., Netter, J., & Yang, T. (2008). The determinants of board structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 87, 308–328.

Lindenberg, E., & Ross, S. (1981). Tobin’s q ratio and industrial organization. Journal of Business, 54, 1–32.

Lipton, M., & Lorsch, W. (1992). A modest proposal for improved corporate governance. Business Lawyer, 48, 59–77.

Loderer, C., & Peyer, U. (2002). Board overlap, seat accumulation, and share prices. European Financial Management, 8, 165–192.

Lorsch, W., & MacIver, E. (1989). Pawns and potentates: The reality of America’s corporate boards. Boston: Harvard University Press.

Maka, Y., & Kusnadi, Y. (2005). Size really matters: Further evidence on the negative relationship between board size and firm value. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 13, 301–318.

Mallin, C. (2002). Corporate governance, institutional investors and socially responsible investment. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 10, 1–3.

Martin, S. (1993). Advanced industrial economics. UK: Blackwell.

MENA (Middle East and North Africa Corporate Governance Workshop). (2003). Corporate governance in Morocco, Egypt, Lebanon and Jordan. The organization of economic co-operation and development (OECD). http://www.gcgf.org/ifcext/cgf.nsf/AttachmentsByTitle/MENA_Sep_03_CG_in_MENA_countries/$FILE/MENA_Sep_03_MENA_CG_Report.pdf (Access: 18 Jun 2006).

MENA–OECD. (2006). Egypt national investment reform agenda. www.oced/mena/investement. (Access: 15 May 2008).

Monks, R., & Minow, N. (1995). Corporate governance. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Mumford, M. (2003). Corporate governance and financial distress: When structures have to change. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 11, 52–64.

Pallant, J. (2001). SPSS survival manual. Buckingham: Open University.

Pfeffer, J., & Salancik, R. (1978). The external control of organizations: A resource-dependence perspective. New York: Harper & Row.

Postma, T., Van Ees, H., & Sterken, E. (2003). Board composition and firm performance in the Netherlands. Research report, Research Institute SOM (Systems, Organizations, and Management), University of Groningen.

Raheja, C. (2005). Determinants of board size and composition: A theory of corporate boards. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 40, 283–306.

ROSC (Report on the observance of standards and codes). (2004). Corporate governance country assessment, World Bank-IMF (http://www.worldbank.org/ifa/rosc_cg_egyp2.pdf). (Access: 3 Jan 2006).

Rousseeuw, P., & Leroy, A. (2003). Robust regression and outliers detection. New Jersey: John Wiley.

Sofia, L., & Vafeas, N. (2009). The relation between board size and firm performance in firms with a history of poor operating performance. Journal of Management and Governance (forthcoming). doi: 10.1007/s10997-009-9091-z.

Tabachnick, B., & Fidell, L. (2001). Using multivariate statistics (3rd ed.). New York: Harper Collins College.

Wels, T. (2007). Corporate governance: Roundtable. http://www.mckinsey.com.

Wen, Y., Rwegasira, K., & Bilderbeek, J. (2002). Corporate governance and capital decisions of the Chinese listed firms. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 10, 75–83.

Yermack, D. (1996). Higher market valuation of companies with a small board of directors. Journal of Financial Economics, 40, 185–212.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the editor and two anonymous reviewers for their professional work and constructive comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Elsayed, K. Board size and corporate performance: the missing role of board leadership structure. J Manag Gov 15, 415–446 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-009-9110-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-009-9110-0