Abstract

Objectives

Intimate partner violence (IPV) around the time of pregnancy is a risk factor for adverse pregnancy and birth outcomes. The supplemental nutrition program for women, infants, and children (WIC), available to low income pregnant women, may provide an opportunity to identify victims of IPV and refer them to services. This cross-sectional study aims to determine whether WIC participants are more likely than non-WIC participants to have reported IPV before or during pregnancy in the United States.

Methods

The 2004–2011 National Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) survey (n = 319,689) was analyzed in 2015. Self-reported WIC participation, pre-pregnancy IPV, and IPV during pregnancy were examined. The associations between IPV and WIC participation were analyzed using multiple logistic regression and adjusted odds ratios with corresponding 95% confidence intervals were calculated. Subpopulation analysis was conducted, stratified by race/ethnicity.

Results

Nearly half of the study sample received WIC (48.1%), approximately 4% of women reported physical abuse 12 months before their most recent pregnancy, and 3% reported abuse during pregnancy. After adjusting for confounders, women who reported IPV before and during pregnancy had significantly higher odds of WIC utilization compared to women who did not report IPV. However, when stratified by race, the association was only significant for non-Hispanic White women (pre-pregnancy AOR 1.47, 95% CI [1.17, 1.85]; during pregnancy AOR 1.47, 95% CI [1.14, 1.88]).

Conclusions for Practice

There is an association between IPV before and during pregnancy and utilization of WIC. Public health professionals and policy makers should be aware of this association and use this opportunity to screen and address the needs of WIC recipients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Significance

Low income pregnant women are at high risk for IPV. The supplemental nutrition program WIC is available to low income pregnant women and may provide an opportunity to identify victims of IPV and refer them to services. The current study found a significant association between IPV around pregnancy and utilization of WIC services. Women who utilize WIC services have higher odds of IPV during preconception period or pregnancy compared to women who do not. To the authors’ knowledge, this is one of the first studies to closely examine the association between IPV and WIC utilization among racial and ethnic groups.

Introduction

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) encompasses any “physical, sexual, or psychological harm by a current or former partner or spouse” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2013) and the lifetime prevalence of IPV in the form of severe physical violence in women in the United States is approximately 22% (Breiding et al. 2014). IPV is an often under reported problem not commonly evaluated during pregnancy (Deshpande and Lewis-O’Connor 2013; Chamberlain and Perham-Hester 2000). About 3 to 9% of pregnant women in the United States experience IPV in the form of severe physical violence (Alhusen et al. 2015), with the rate increasing to as high as 12% after delivery (Scribano et al. 2012).

There is growing evidence signifying the consequences of IPV on the health of the women especially around the time of pregnancy. Sequelae of IPV include physical injuries, sexually transmitted infections, repeat spontaneous abortions, depression, post traumatic syndrome, suicide attempts and death (Sharps et al. 2007). Furthermore, IPV is linked to delayed or inadequate prenatal care, preterm births, small for gestational age, low birth weight infants, and neonatal death (Coker et al. 2004). However, most IPV victims do not seek help from health care providers due to feelings of shame, fear of stigma, and lack of screening or inquiry by health care providers (Deshpande and Lewis-O’Connor 2013).

Previous studies have reported higher rates of IPV before and during pregnancy among women living in low socio-economic conditions. Low educational background, low income, or poverty, coverage by Medicaid and/or public health insurance program, and limited access to health care were found to be significantly associated with IPV before and during pregnancy (Chu et al. 2010; Weinbaum et al. 2001). Medicaid-covered delivery is a significant predictor of IPV before and during pregnancy (Jasinski 2004). Additionally, data from the California Women’s Health Survey revealed that women who reported food insecurity experienced increased odds of IPV (Ricks et al. 2016).

Low income pregnant women in the United States are disproportionately affected by adverse pregnancy and birth outcomes (Blumenshine et al. 2010). Infant mortality rates, preterm birth, and low birth weight are more prevalent among low income women than their high income counterparts (Blumenshine et al. 2010). Additionally, low income pregnant women were more likely to have three or more chronic diseases or related risk factors including: obesity, chronic hypertension, pregnancy induced hypertension, postpartum depressive symptoms, and gestational diabetes (Bombard et al. 2012).

The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), Supplemental Nutrition Program (SNAP), Medicaid, and home visiting and case management programs are a few of the resources designed to ameliorate factors contributing to adverse outcomes facing low income mothers (Crouse et al. 2007; U.S. Department of Agriculture [USDA] 2019). Unlike most government funded assistance services, WIC provides a wide range of extended benefits to mothers and children (USDA 2019). Specifically, WIC safeguards the wellbeing of low-income pregnant, postpartum, breastfeeding and formula feeding women, infants, and children up to age five by providing nutritious foods to supplement diets, information on healthy eating including breastfeeding promotion and support, health screening, and referrals to health care and social services (USDA 2019). WIC aims to improve nutrition and adequate weight gain during pregnancy for women with nutritional or medical risk. Moreover, research has demonstrated that women receiving WIC services are more likely to give birth to a healthy birth weight, full term baby than those who are eligible but not receiving services (Hoynes et al. 2009).

Many low income women who are at risk of adverse health outcomes often come in contact with WIC. Consequently, WIC providers can play an important role in screening and referring at risk mothers to essential services. Currently, WIC has no specific screening or referral services to address IPV around the time of pregnancy” (USDA 2019). Identifying IPV as a priority and developing strategy to address IPV in the WIC programs can be highly beneficial in the prevention of adverse birth outcomes related to IPV around the time of pregnancy. Given IPV is more prevalent among low income women, prior studies hypothesized the association between WIC and IPV. However, studies were descriptive and did not test the level of association and were not specific to IPV among pregnant and preconception women (Weinbaum et al. 2001). Therefore, this study aims to examine the association between IPV before and during pregnancy and WIC participation. We hypothesize that women who participate in WIC program are more likely than non-WIC participants to have reported IPV during preconception period or pregnancy. Moreover, previous studies have indicated that prevalence of IPV varies by race and the rate of IPV is higher among racial/ethnic minority groups compared to the non-Hispanic Whites (Cho 2012). Further, Anderson’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Use suggests an association between utilization of WIC services and race (Babitsch et al. 2012). Therefore, the current study also aims to examine the role of race in the association between IPV and utilization of WIC services.

Methods

Data Sources

Data used for the current study come from the 2004 to 2011 National Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) survey consisting of 319,689 postpartum women (Phase 5: 2004–2008 and phase 6: 2009–2011, combined) from 40 states representing 78% of all U.S. live births. PRAMS is a surveillance program conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in collaboration with state health departments (CDC 2016). It collects information on maternal attitudes and experiences before, during, and shortly after pregnancy. Each year, between 1300 and 3400 women, who have had a recent live birth, are sampled from the respective state’s birth certificate file. A complex multistage sampling design was utilized and appropriate sampling, nonresponse, and non-coverage weights were applied. Women from racial/ethnic minority groups and at-risk population were oversampled to conduct reliable in-depth analysis of the small groups. PRAMS currently uses a minimum response rate of 65% for state release of data. PRAMS used a standardized data collection methodology including mailed questionnaires and telephone surveys with multiple follow-up attempts. Responses from the survey were linked to the corresponding birth certificate data for analysis. The survey was conducted in accordance with prevailing ethical principles. Detailed PRAMS data collection methodology is published elsewhere (CDC 2016).

Study Population

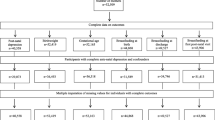

Women who had a recent singleton, live birth were included in this study. Women with multiple births (n = 14,741) and those without a valid response to the questions on intimate partner violence and WIC (n = 16,753) were excluded from the analysis (total 9.9%), resulting in a final sample size of 288,195 women. Women excluded from the analyses due to multiple births were at higher risk of pregnancy related complications and adverse birth outcomes (Su et al. 2015).

Study Measures

Pre-pregnancy IPV and IPV during pregnancy were determined using items on the PRAMS survey questionnaire. Women were asked “if either their husband or partner had pushed, hit, slapped, kicked, choked, or physically hurt them in any way;” 12 months before becoming pregnant with their most recent child and the response options were “yes” and “no” (Basile et al. 2007). This variable was coded as a dichotomous variable (Yes/No) with ‘Yes’ indicating experience of IPV and ‘No’ indicating no experience of IPV, in the 12 months preceding their most recent pregnancy according to the convention of prior studies (Basile et al. 2007; Chu et al. 2010). To determine IPV during pregnancy, women were asked the same question for the period during their most recent pregnancy and this variable was coded in the same manner (yes/no).

The outcome variable, utilization of WIC services, was examined using one survey item on the PRAMS questionnaire. Respondents were asked if they were on WIC (the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children) during their most recent pregnancy. Women who reported receiving WIC services were coded as ‘Yes’ and those who did not receive WIC services were coded as ‘No’. Based on previous literature review, several additional factors were assessed as potential confounders (CDC 2013). Covariates included sociodemographic factors such as maternal age (< 18; 20–24; 25–29; 30–34; 35 + years), race/ethnicity (Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and Non-Hispanic Other), maternal and paternal education (< 12; 12; > 12 years), and marital status (Married; Not Married). Insurance status during pregnancy was coded as private (including private, military, or other), Medicaid and no insurance). Prenatal care utilization was assessed using the Kotelchuck Index (Inadequate; Intermediate; Adequate; Adequate Plus) (Kotelchuck 1994). Barriers to early prenatal clinic visit were also examined and coded as ‘none’, ‘1 to 2’, ‘3 to 4’, and ‘5 or more’. Reproductive factor such as pregnancy intention (Intended; Unintended) was also included as covariate. Breastfeeding including, initiation (Yes/No) and duration (did not; ≤ 8 weeks; > 8 weeks) were assessed.

Statistical Analysis

Data analyses were conducted using survey procedures in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) utilizing appropriate analysis weights to account for the complex survey design. The study was exempted from review by the Institutional Review Board at Virginia Commonwealth University. Descriptive analysis was conducted to examine the distribution of the study population and weighted and unweighted frequencies were generated. The associations between IPV before and during pregnancy and utilization of WIC service were determined using logistic regression analysis, which generated crude and adjusted odds ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). Parsimonious logistic models were created using the 10% change-in-estimates procedure to identify the confounders in the associations (Maldonado and Greenland 1993). Possible effect modifiers, specifically race, were assessed using interaction terms composed of exposure and possible effect modifiers. Race and IPV were found to have a statistically significant interaction for both before and during pregnancy (p value = 0.0008 and 0.0007, respectively) and data was stratified by race. Different sets of confounders in the associations between IPV before and during pregnancy and utilization of WIC services were identified for different strata of race/ethnicity using the 10% change-in-estimates procedure. Therefore, a separate model with a different set of adjusting variables was analyzed for each strata of race/ethnicity. The level of significance for all tests was set to p < 0.05.

Results

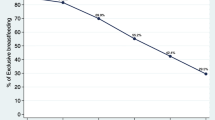

Nearly half of the study sample received WIC (48.1%), approximately 4% of women reported physical abuse 12 months before their most recent pregnancy, and 3% reported abuse during pregnancy (not shown in tables). Majority of the women in the study were 25 years or older (67.3%), non-Hispanic White (60.4%), married (62.1%), had more than 12 years of education (54.5%), and were privately insured (58%) (Table 1). Rao-Scott Chi square tests showed a statistically significant association between all the covariates and IPV before and during pregnancy (Table 1). Figures 1 and 2 display racial distribution of WIC participation by IPV before and during pregnancy, respectively. The rates of WIC participation were higher among abused women compared to the non-abused women across all race/ethnicities for both before and during pregnancy, however, the differences were more pronounced among non-Hispanic White and Hispanic women.

Table 2 shows that WIC participation was significantly associated with age, race/ethnicity, marital status, educational status, insurance status, adequacy of prenatal care, number of barriers to prenatal care, pregnancy intention, and breastfeeding in the bivariate logistic regression analysis. Women who reported IPV before or during pregnancy had significantly higher prevalence of WIC participation compared to women who did not report IPV (72.1% vs. 44.4% or 73.2% vs. 44.5%, respectively). IPV, both before and during pregnancy, were significantly associated with WIC participation (Crude odds ratio [COR] 3.24, 95% CI 3.01, 3.48; COR 3.41, 95% CI 3.14, 3.69] respectively). These associations were attenuated but remained statistically significant even after adjusting for age, educational status, marital status, insurance status, number of barriers to prenatal care visits, and pregnancy intention (Adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 1.29, 95% CI 1.10, 1.50; AOR 1.24, 95% CI 1.04, 1.47; respectively) (Table 3).

Table 4 presents odds of WIC utilization stratified by race/ethnicity. The unadjusted models show significant, positive associations between IPV (before and during pregnancy) and utilization of WIC across all racial/ethnic groups. However, after adjusting for different sets of potential confounders for different strata of race/ethnicity (Table 4 footnotes), the associations between IPV and WIC utilization, before (AOR 1.47, 95% CI 1.17, 1.85) and during (AOR 1.47, 95% CI 1.14, 1.88) pregnancy remained statistically significant for only non-Hispanic White women. There were no statistically significant associations for non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic and non-Hispanic other women.

Discussion

This study showed there is a statistically significant association between IPV and WIC utilization. Specifically, Non-Hispanic white women who receive WIC had a statistically higher odds of experiencing IPV before and during pregnancy. However, the association was not significant in Non-Hispanic black, Non-Hispanic other, and Hispanic women. To the author’s knowledge there were no previous studies that explored racial/ethnic differences in the association between IPV and WIC utilization. Nonetheless, the findings of this study are consistent with previous study that reported higher prevalence of IPV among WIC participants (Weinbaum et al. 2001).

This study highlighted an important finding; Non-Hispanic white women who receive WIC had higher odds of experiencing IPV. However, the lack of significance in other ethnic/racial groups may be due to under-reporting. Previous literature suggests that disclosure of IPV and attempt to seeking services among certain racial or ethnic groups may be deterred by distrust of healthcare providers, lack of cultural sensitivity surrounding IPV interventions, fear of stigmatization, and inability to access services (Montalvo-Liendo et al. 2008). Further, cultural beliefs may prevent women from disclosing IPV—especially to anyone outside of their own family. This may occur particularly among Hispanic or South Asian women who tend to believe that family issues should be kept private (Flicker et al. 2011; Sylaska and Edwards 2014).

Although wide variations of prevalence of IPV have been reported, factors including partner’s pregnancy intention, recent divorce or separation, and young maternal age or lower level of education—have been identified to increase a woman’s risk of experiencing IPV around the time of pregnancy (Bailey 2010; Chu et al. 2010). Conversely, IPV has serious consequences affecting the health of the mother and infant (Hill et al. 2016). Studies have shown that abused women are more likely to sustain physical injuries, have mental health problems, sexually transmitted diseases, rapid repeat pregnancy, abortion, and poor birth outcomes including preterm birth, small for gestational age, low birthweight births and neonatal deaths. Further, homicide is one of the main causes of intentional injury related maternal mortality (Romero and Pearlman 2012).

To prevent these deleterious consequences, it is important that pregnant women are screened for IPV. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommend that physicians should screen all women for IPV during obstetric care beginning the first prenatal visit, at least once per trimester, and at the postpartum checkup (The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2012). However, recent studies suggest many pregnant women are not routinely evaluated for IPV and most clinicians only conduct screening for violence when obvious warning signs are observed (Deshpande and Lewis-O’Connor 2013). According to a national survey, only 17% of prenatal care providers routinely screen for IPV on the first visit, and only 5% screen on follow-up visits (Chamberlain and Perham-Hester 2000).

Women have increased interaction with the healthcare and social services during pregnancy and victims come in contact with the health care delivery system as often as non-abused women (Campbell 2002). Thus, pregnancy offers a unique opportunity for IPV screening and intervention. For women who do not have health insurance but are eligible to receive WIC services, WIC may be the only opportunity to seek help. This is particularly important for non-Hispanic White women coming through WIC clinics. Although increased odds of WIC utilization among those who experienced IPV were only statistically significant for Non-Hispanic white women, the reported prevalence of IPV is alarmingly high for all women. Since barriers to disclosing IPV were noted among racial and ethnic minorities (Flicker et al. 2011; Sylaska and Edwards 2014), it is important to ensure both screening and intervention are provided in a culturally sensitive and trauma-informed manner (Ghandour et al. 2015; Montalvo-Liendo et al. 2008).

To the authors’ knowledge, this is one of the first studies to closely examine the association between IPV and WIC utilization among racial and ethnic groups. This study utilized a large nationally representative sample of U.S. women with live births that is generalizable. Findings from the current study contributes to the scant body of literature examining the potential role of WIC as a resource to IPV victims. Considering IPV is notably under reported and women are not routinely screened by health care providers, this study highlights the importance of WIC offices as a possible venue for identifying victims and provision of referrals.

Despite its strengths, this study has some limitations. Due to the cross-sectional nature of the study, it will be difficult to infer temporality between IPV experience and receipt of WIC services. However, the study affirms that the prevalence of IPV among women receiving WIC services are high. Nonetheless, women in this study may also have under-reported IPV and it is possible that the lack of significance in the association between IPV and WIC utilization in minority groups may be due to under reporting. Therefore, caution should be exercised in interpreting this finding. Further, other forms of IPV, such as emotional and sexual abuse, are not assessed in PRAMS survey; therefore, current study addresses reported physical violence only. Also, PRAMS only includes women with a live birth, therefore the study could not assess women with still births or miscarriages.

Women who utilize WIC services have higher odds of IPV during preconception period or pregnancy compared to women who do not. Victims of IPV come in contact with the health and social service systems without being detected. Regardless of insurance status, WIC provides services to low income women and provides an opportunity for screening and referral. WIC offices may need additional staffing and training to effectively screen and refer victims to services. Future studies are needed to investigate the efficacy of implementing IPV screening and referral in WIC offices. Additionally, research should focus on culturally sensitive IPV interventions that take race and ethnicities into consideration.

References

Alhusen, J. L., Ray, E., Sharps, P., & Bullock, L. (2015). Intimate partner violence during pregnancy: Maternal and neonatal outcomes. Journal of Women’s Health, 24(1), 100–106. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2014.4872.

Babitsch, B., Gohl, D., & Lengerke, T. (2012). Re-revisiting Andersen’s behavioral model of health services use: A systematic review of studies from 1998–2011. GMS Psycho Social-Medicine, 9, 1–15.

Bailey, B. A. (2010). Partner violence during pregnancy: Prevalence, effects, screening, and management. International Journal of Women’s Health, 2, 183–197.

Basile, K. C., Hertz, M. F., & Back, S. E. (2007). Intimate partner violence and sexual violence victimization assessment instruments for use in healthcare settings. Version 1.0. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipv/ipvandsvscreening.pdf.

Blumenshine, P., Egerter, S., Barclay, C. J., Cubbin, C., & Braveman, P. A. (2010). Socioeconomic disparities in adverse birth outcomes: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 39(3), 263–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2010.05.012.

Bombard, J. M., Dietz, P. M., Galavotti, C., England, L. J., Tong, V. T., Hayes, D. K., et al. (2012). Chronic diseases and related risk factors among low-income mothers. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 16(1), 60–71.

Breiding, M. J., Smith, S. G., Basile, K. C., Walters, M. L., Chen, J., & Merrick, M. T. (2014). Prevalence and characteristics of sexual violence, stalking and intimate partner violence victimization: National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, United States 2011. MMWR, 63(SS08), 1–18.

Campbell, J. C. (2002). Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet, 359(9314), 1331–1336.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Intimate partner violence. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). Detailed PRAMS methodology. http://www.cdc.gov/prams/methodology.htm.

Chamberlain, L., & Perham-Hester, K. A. (2000). Physicians’ screening practices for female partner abuse during prenatal visits. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 4(2), 141–148.

Cho, H. (2012). Racial differences in the prevalence of intimate partner violence against women and associated factors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27, 344–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260511416469.

Chu, S. Y., Goodwin, M. M., & D’Angelo, D. V. (2010). Physical violence against US women around the time of pregnancy, 2004–2007. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 38(3), 317–322.

Coker, A. L., Sanderson, M., & Dong, B. (2004). Partner violence during pregnancy and risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Pediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 18(4), 260–269. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3016.2004.00569.x.

Crouse, G., Douglas, S., & Hauan, S. (2007). Indicators of welfare dependence: Annual Report to Congress, 2007. Retrieved from https://www.ntis.gov/Search/Home/titleDetail/?abbr=PB2009101363.

Deshpande, N. A., & Lewis-O’Connor, A. (2013). Screening for intimate partner violence during pregnancy. Reviews in Obstetrics and Gynecology, 6(3–4), 141–148. https://doi.org/10.3909/riog0226.

Flicker, S. M., Cerulli, C., Zhao, X., Tang, W., Watts, A., Xia, Y., et al. (2011). Concomitant forms of abuse and help-seeking behavior among white, African American, and Latina women who experience intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women, 17(8), 1067–1085.

Ghandour, R. M., Campbell, J. C., & Lloyd, J. (2015). Screening and counseling for intimate partner violence: A vision for the future. J Womens Health, 24(1), 57–61. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2014.4885.

Hill, A., Pallitto, C., McCleary-Sills, J., & Garcia-Moreno, C. (2016). A systematic review and meta-analysis of intimate partner violence during pregnancy and selected birth outcomes. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 133, 269–276.

Hoynes, H., Page, M., Stevens, A. (2009). Is WIC a better start? Evaluating WIC’s impact on infant health using program introduction. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 15589. Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/papers/w15589.pdf.

Jasinski, J. (2004). Pregnancy and domestic violence: A review of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse, 5(1), 47–64.

Kotelchuck, M. (1994). An evaluation of the Kessner adequacy of prenatal care index and a proposed adequacy of prenatal care utilization index. American Journal of Public Health, 84(9), 1414–1420.

Maldonado, G., & Greenland, S. (1993). Simulation study of confounder-selection strategies. American Journal of Epidemiology, 138(11), 923–936.

Montalvo-Liendo, N. (2008). Cross-cultural factors in disclosure of intimate partner violence: An integrated review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65(1), 20–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04850.x.

Ricks, J. L., Cochran, S. D., Arah, O. A., Williams, J. K., & Seeman, T. E. (2016). Food insecurity and intimate partner violence against women: Results from the California Women’s Health Survey. Public Health Nutrition, 19(05), 914–923.

Romero, V. C., & Pearlman, M. (2012). Maternal mortality due to trauma. Seminars in Perinatology, 36(1), 60–67. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semperi.2011.09.012.

Scribano, P. V., Stevens, J., & Kaizar, E. (2012). The effects of intimate partner violence before, during, and after pregnancy in nurse visited first time mothers. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 1, 12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-012-0986-y.

Sharps, P. W., Laughon, K., & Giangrande, S. K. (2007). Intimate partner violence and the childbearing year: Maternal and infant health consequences. Trauma Violence Abuse, 8(2), 105–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838007302594.

Su, R., Zhu, W., Wei, Y., et al. (2015). Maternal and neonatal outcomes in multiple pregnancy: A multicentre study in the Beijing population. Chronic Diseases and Translational Medicine, 1(4), 197–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cdtm.2015.08.004.

Sylaska, K. M., & Edwards, K. M. (2014). Disclosure of intimate partner violence to informal social support network members: A review of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse, 15(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838013496335.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2012). Committee opinion: Intimate Partner Violence. The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 518. Retrieved from http://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Health-Care-for-Underserved-Women/Intimate-PartnerViolence.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2019). Women, infants, and children (WIC). Retrieved from http://www.fns.usda.gov/wic.

Weinbaum, Z., Stratton, T. L., Chavez, G., Motylewski-Link, C., Barrera, N., & Courtney, J. G. (2001). Female victims of intimate partner physical domestic violence (IPP-DV), California 1998. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 21(4), 313–319.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) Working Group for the approval of data analyses. The PRAMS Working Group: Alabama—Izza Afgan, MPH; Alaska—Kathy Perham-Hester, MS, MPH; Arkansas—Mary McGehee, PhD; Colorado—Alyson Shupe, PhD; Connecticut—Jennifer Morin, MPH; Delaware—George Yocher, MS; Florida—Alisa Simon; Georgia—Qun Zheng, MS; Hawaii—Jihae Goo; Illinois—Patricia Kloppenburg, MT (ASCP), MPH; Iowa—Sarah Mauch, MPH; Louisiana—Megan O’Connor, MPH; Maine—Tom Patenaude, MPH; Maryland—vacant; Massachusetts—Emily Lu, MPH; Michigan—Peterson Haak; Minnesota—Mira Grice Sheff, PhD; Mississippi—Brenda Hughes, MPPA; Missouri—David McBride, PhD; Montana—JoAnn Dotson; Nebraska—Brenda Coufal; New Hampshire—David J. Laflamme, PhD, MPH; New Jersey—Lakota Kruse, MD; New Mexico—Oralia Flores; New York State—Anne Radigan; New York City—Candace Mulready-Ward, MPH; North Carolina—Kathleen Jones-Vessey, MS; North Dakota—Sandra Anseth; Ohio—Connie Geidenberger, PhD; Oklahoma—Alicia Lincoln, MSW, MSPH; Oregon—Claudia W. Bingham, MPH; Pennsylvania—Tony Norwood; Rhode Island—Karine Tolentino Monteiro, MPH; South Carolina—Mike Smith, MSPH; Texas—Tanya Guthrie, PhD; Tennessee—Ramona Lainhart, PhD; Utah—Nicole Stone; Vermont—Peggy Brozicevic; Virginia—Christopher Hill, MPH, CPH Washington—Linda Lohdefinck; West Virginia—Melissa Baker, MA; Wisconsin—Christopher Huard; Wyoming—Amy Spieker, MPH; CDC PRAMS Team, Applied Sciences Branch, Division of Reproductive Health

Funding

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SWM developed the research question and designed the study. SWM and SSR developed the statistical analysis plan and SSR analyzed the data. All authors participated in reviewing and interpreting the results and contributed substantively to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None of the authors have conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Masho, S.W., Rozario, S.S. & Ferrance, J.L. Intimate Partner Violence Around the Time of Pregnancy and Utilization of WIC Services. Matern Child Health J 23, 1648–1657 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-019-02811-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-019-02811-7