Abstract

Objective

Analyze the association between household food security status and diet quality during pregnancy.

Methods

Cross-sectional analysis of pregnant women from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey from 1999 to 2008. Of the 1158 pregnant women with complete household food security information, we analyzed 688 women who had complete dietary information and household incomes ≤300 % of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL). Diet quality was measured by the Alternate Healthy Eating Index modified for Pregnancy (AHEI-P) from 1 to 2 24 h dietary recalls. Multivariate linear and logistic regression models were implemented to assess the association between household food security status and AHEI-P, adjusting for age, nativity, marital status, race/ethnicity, education, and household income.

Results

Among women with household incomes ≤300 % of the FPL, 19 % were food insecure and 4 % were marginally food secure. The mean AHEI-P score was 41.9 (95 % CI 40.4, 43.3). Household food insecurity was not associated with overall diet quality. However, living in a food insecure household compared to a food secure household was associated with a 2.3 (1.3, 4.1) greater odds of having a calcium component score greater than the median intake of calcium scores among food secure women in the sample.

Conclusions for Practice

In a nationally representative sample of pregnant women, 80 % lived in a fully food secure household. Improving household food security during pregnancy is a public health opportunity to improve health outcomes; however household food security status may not be associated with overall diet quality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Significance

What is already known on this subject? Experiencing household food insecurity during pregnancy is associated with an array of poor health outcomes including gestational weight gain and diabetes.

What this study adds? The prevalence of household food insecurity in this nationally representative sample of pregnant women is 14 %. We found no association between household food insecurity and overall diet quality, which suggests that food insecurity may lead to adverse health outcomes through other mechanisms.

Objectives

Adequate consumption of nutrients during pregnancy is possibly the single most important environmental factor influencing pregnancy outcomes [20]. Poor diet quality during pregnancy has been associated with maternal preeclampsia [33] and adverse infant health outcomes such as insulin resistance [14], fetal growth restriction [35], neural tube defects and orofacial clefts [5]. Diet quality is also an important modifiable risk factor for the most prevalent health issue facing American pregnant women today; excessive gestational weight gain [30].

Household food insecurity exists “whenever the availability of nutritionally adequate and safe food, or the ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways, is limited or uncertain” [8]. In 2013, one in seven households (14.3 %) in the United States experienced food insecurity [6]. However, the national prevalence of pregnant women living in food insecure households is unknown [18]. Cohort studies that have assessed food insecurity during pregnancy have reported a wide range of prevalence estimates and they are all consistently >15 % [24, 3, 17, 4].

Previous studies have shown that stress and food scarcity, which are both components of food insecurity, are associated with negative changes in diet [1, 38]. Pregnant women experiencing stress are more likely to have a higher intake of total energy and fats compared to pregnant women who are not stressed [11]. Similarly, women experiencing hunger from not having enough food consume less fruits and vegetables than those who have enough food [34]. Diet quality has also been implicated by researchers who have found household food insecurity to lead to gestational weight gain and other pregnancy complications [23].

The Special Supplemental Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) serves approximately 2 million pregnant women every month and is designed to improve food security and nutrition [42]. WIC is designed to improve food security through nutrition education and WIC vouchers that are given to participants that may only be reimbursed for specified healthy foods [42]. Research suggests WIC participation is associated with higher diet quality [2]. Therefore, we hypothesize that the relationship between food insecurity and diet quality will be differential by WIC participation, where participation in WIC will attenuate any observed negative association between household food insecurity and diet quality.

Our study has three aims; (1) identify the prevalence of pregnant women who live in food insecure households in the United States; (2) examine the extent to which household food insecurity is associated with diet quality among pregnant women; and, (3) assess whether WIC participation modifies the association between household food insecurity and overall diet quality.

Methods

This cross-sectional study used data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). NHANES is an ongoing multistage survey administered by the National Center for Health Statistics, which selects a nationally representative sample of the noninstitutionalized United States civilian population [28]. NHANES data from waves 1999 through 2008 were combined to increase the sample of pregnant women. There were 1158 women in NHANES waves 1999–2008 with complete information on household food security. We used this sample to estimate the national prevalence of food insecurity among pregnant women. For our main analysis, we restricted our population to the 688 women with household incomes ≤300 % of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) because <4 % of those with household incomes 300–400 % of the FPL were food insecure or marginally food secure. When testing for effect modification of the food insecurity and overall diet quality relationship by WIC participation status (WIC participant, income eligible non-participant, and income ineligible), we restricted the population to those who were financially eligible to participate in WIC (≤185 % of the FPL) and compared the relationship between household food security status and overall diet quality among WIC participants and income-eligible non-participants.

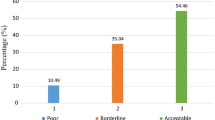

Household food security status was derived from the United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) validated Standard Food Security Survey Module, which is used in NHANES [13]. A household respondent is asked ten questions if the household does not contain children and 18 if it does contain children. Responses to the questions are used to categorize households into one of four groups: full food security, marginal food security, low food security, and very-low food security. The low (n = 115) and very-low food security (n = 47) groups were combined due to small cell sizes to create a food insecure category. For the analytic sample, we combined the marginal food secure group of women (n = 106) with the food insecure group because of the ample research showing the negative health effects of living in a marginally food secure household [24, 22, 7]. Therefore, in the analytic sample, households were classified as food secure if 0 questions were answered affirmatively, and food insecure if 1 or more questions were answered affirmatively.

The Alternate Healthy Eating Index modified for Pregnancy (AHEI-P) was used to measure diet quality from 1–2 24 h dietary recalls. From 1999 to 2002, NHANES collected one 24-h dietary recall, and from 2003 to 2008 NHANES collected two 24-h dietary recalls. Diet quality was averaged across the 24-h recalls for those who had two recalls collected. The AHEI-P is a variation of the Alternate Healthy Eating Index that does not consider alcohol intake and the “nuts and soy protein” component of the index as pregnant women often avoid these foods during pregnancy [33]. However, the AHEI-P has component scores for calcium, folate, and iron intake because adequate intakes of these nutrients are important during pregnancy. Our calculation of the AHEI-P does not consider the consumption of trans-fats, as trans-fat information is not available in NHANES. Therefore, diets were evaluated across 8 components of the AHEI-P index: vegetables, fruit, and ratio of white to red meat, fiber, ratio of polyunsaturated to saturated fatty acids, folate, calcium, and iron. The maximum score was 80, as each of the 8 components were scored from 0 to 10. Supplementation is not considered in the calculation of the nutrient scores.

The AHEI-P variable was square root transformed for the analysis so the distribution of AHEI-P scores would better approximate a normal distribution. However, all values reported in the manuscript have been transformed back to the original AHEI-P scale. The AHEI-P component scores were not normally distributed and even after transforming the scores, regression diagnostics revealed that the distributions violated assumptions of linear regression. Additionally, the skewed distributions of the component scores prevented us from analyzing tertiles or quartiles. Therefore, we created binary component score variables that indicated if an individual had a high or low component score, where the variable was coded 0 if the component score for the individual was less than the median component score among the food secure women in the sample, and 1 if the component score was greater than the median component score among the food secure women in the sample. Women who had the median score were not included in the component score analyses.

Age (≤20, >20 and ≤30, >30), education level (high school diploma or less, any college experience), household income (FPL ≤ 100, >100 and ≤200, >200 and ≤300 %), and race/ethnicity (Hispanic, Non-Hispanic White & Other Race, Non-Hispanic Black) were considered a priori to be included as confounders. Additionally, nativity (born in the US, foreign born), and marital status (married or living with a partner or spouse, divorced/separated/single/widowed) were added as confounders because they were significantly associated with overall diet quality and household food security (p < 0.20). Household size (<3 people, ≥4 people), current health insurance coverage (insured, uninsured), and trimester of pregnancy (first, second, third), were not significantly associated with overall diet quality and household food security (p < 0.20) and were excluded from all models. The association between the day/s of the week the 24 h recall/s were taken (1–2 weekdays, 1–2 weekend days, and 1 weekday and 1 weekend day) and overall diet quality was tested to determine if adjusting for the day/s of the week the recall/s were collected would improve precision. However, the day/s of the week the recall/s were collected was not associated with overall diet quality (p < 0.20) and therefore was not included in any model.

Design-based F tests and multivariate linear regressions were used to examine the covariate relationships with food insecurity and AHEI-P scores. Multivariate linear regression was used to estimate the adjusted relationship between household food security status and total AHEI-P score. Models were adjusted for race/ethnicity, age, household income, education, nativity, and marital status. Adjusted logistic regressions were implemented to describe the relationship between household food security and each AHEI-P component score. A Wald test was implemented to assess effect modification of the household food security and overall diet quality relationship by WIC participation; a cutoff of p < 0.20 was implemented. A category for each covariate was created for women who had missing information; this was done to preserve sample size. Random effect models were implemented to identify the proportion of the total variance due to between-person variability for all dietary estimates. All standard deviations reported reflect the between-person variability in the estimates; within-person variation due to having multiple recalls has been partitioned out. Complex dietary and survey weights were applied according to NHANES protocol to preserve the representativeness of the sample, and therefore survey commands were used throughout the analysis [28]. STATA (version 12.0, StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) was used for all statistical analysis. Participants were treated ethically in accordance with NHANES protocol, which was approved by The National Center for Health Statistics Research Ethics Review Board [27].

Results

Among the 1158 pregnant women from NHANES 1999–2008, 12 % lived in food insecure households and 9 % lived in marginally food secure households.

All other results refer to the analytic sample of women with complete dietary information and with household incomes ≤300 % of the FPL, where 19 % lived in food insecure households and 14 % lived in a marginally food secure household. On average, pregnant women were 25.6 ± 5.6 years of age, and 43 % had some education beyond high school (Table 1). The sample was racially and ethnically diverse; approximately 28 % were Latinas, 25 % were non-Hispanic Black, and 48 % were either non-Hispanic White or of another racial group. Seventy-four percent of women were born in the United States.

The mean AHEI-P score was 41.9 ± 11.7, which is slightly greater than half of the maximum score of 80. Of the different AHEI-P components, pregnant women scored highest in the “Polyunsaturated to saturated fat ratio” component, and the specific nutrient components; calcium, folate, and iron (Table 2). Pregnant women scored the lowest in the “Fruit” and “Vegetable” components.

The association between household food security status and overall diet quality was not statistically significant (Table 3). However, living in a food insecure household compared to a food secure household was associated with a 2.3 (1.3, 4.1) greater odds of having a calcium component score greater than the median intake of calcium scores among food secure women in the sample. All other associations between household food security and AHEI-P component scores were not statistically significant.

We did not observe significant effect modification of the household food insecurity and overall diet quality relationship by WIC participation in the subgroup analysis (p < 0.20).

Conclusions for Practice

Among all pregnant women, 12 % lived in a food insecure household and 9 % lived in a marginally food secure household during the 10-year period. This level of household food insecurity is consistent with the national prevalence, which roughly averaged 11 % from 1999 to 2008 [29]. Among pregnant women with household incomes ≤300 % of the FPL, a full third experienced some level of household food insecurity. Past cohort studies have consistently reported prevalence estimates >15 % [24, 3, 17, 4], however their estimates reflect the proportion of women who experience food insecurity at any time during their pregnancy, and therefore are collected retrospectively. In contrast, this study took a sample of pregnant women across different trimesters and asked them about their food security status in the past 12 months. Therefore it is possible that some of the women who reported full food security in this sample may experience food insecurity in the remaining duration of their pregnancy, and similarly, it is possible that women in our study reported episodes of food insecurity that occurred in the months leading up to their pregnancy. Although the different methods for measuring household food insecurity during pregnancy may answer slightly different questions, the takeaways from our estimate are clear; the national prevalence estimate of 12 % implies household food security status does not improve during pregnancy, and household food insecurity is affecting hundreds of thousands of pregnant women in the United States every year [9].

The mean AHEI-P score of this sample of pregnant women with household incomes ≤300 % of the FPL was 41.9 ± 11.7, which is substantially lower than what has been observed in comparable dietary indices of higher-income groups [33, 35]. Rifas-Sherman et al. [33] conducted an analysis of 1777 English speaking pregnant women from Massachusetts with higher average incomes and found, after excluding the trans-fat category for comparison, women had an average AHEI-P score of 52.3. The greater score of the higher-income sample was most largely accounted for by their better scores in the “fruits” and “vegetables” components, which were both more than 2 points higher on average than what was observed in this sample. The study also found 5 point changes in AHEI-P to be significantly associated with lower blood glucose and slightly lower odds of preeclampsia. Additional studies using AHEI-P and other dietary indices during pregnancy have found lower quality diets to be associated with lower birth weights and lengths, and greater insulin resistance [14, 35]. Our finding of low diet quality scores in a sample of lower-income pregnant women is consistent with past research [40, 12]. Given the importance of diet quality during pregnancy, the gap in diet quality between low- and high-income pregnant women remains a pressing concern.

Finding that food insecurity was not associated with overall diet quality among pregnant women was not expected. Research has found that household food insecurity is associated with poorer diet quality among seniors [36], women of childbearing age [38, 19], and to a lesser extent, children [31]. When no association is found between household food insecurity and diet quality among children, it is often attributed to a household buffering effect, where older household members reduce their intakes to protect children from having to alter their intakes [26]. Given pregnant women are typically viewed as a vulnerable population;[10] it is possible that a similar buffering mechanism is adapted by a household when a member becomes pregnant. However this phenomenon was not analyzed in this study and has not been largely studied in pregnant women.

The finding that household food insecurity was positively associated with calcium intake was unexpected but important, as adequate calcium intake is needed in pregnancy to meet maternal and fetal bone requirements and has been associated with lower risks of preterm delivery, preeclampsia and other poor health outcomes [25, 15, 39]. Post hoc analyses indicated there was no significant effect modification by WIC participation in the household food insecurity and calcium relationship; the relationship between household food insecurity status and calcium intake did not vary significantly among those participating in WIC and eligible non-participants (data not shown). Women from food insecure households may rely more heavily on inexpensive calcium rich foods and calcium fortified juice drinks compared to women from food secure households. For example, women in food insecure households may consume more inexpensive mixed dishes (e.g., pizza, pasta dishes, macaroni and cheese, burritos, tacos, and tamales) which share dairy as a common ingredient, and significantly contribute to the calcium intake in the American diet [16]. However, more studies are needed to reproduce and explore this novel finding.

NHANES is a cross-sectional study, which prevents determining causality. Food security status was assessed in a 12 month time frame, but diet quality was not concurrently assessed over this same time frame, limiting our ability to determine whether diet quality was assessed at a time of food shortage or food anxiety. Although the 24 h recall is an effective tool for gathering dietary information, misreporting can be an issue with any self-reported dietary measure [32]. Women varied in the number of 24 h recalls they completed, and the recalls were collected on different days, at different times of the month, and in different months. These differences in diet quality assessment may introduce variability into the diet quality measures as people consume different foods on different days and in different months [41]. This variability may influence the precision, but not the accuracy of our estimates [37]. WIC participation is often underreported when using self-report data which may result in some misclassification of participation [21]. Additionally, although a woman may be income-eligible for WIC, it is a requirement of the program to have some nutritional risk to participate, and such a risk was not measured in this study [42]. Participation in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program may also impact the relationship between household food insecurity and diet quality, however we did not feel confident assessing effect modification by SNAP participation because few women participated in SNAP in this sample. Finally, having more detailed information on the number of adults and children in the household may have reduced unmeasured confounding. Strengths of this study include the national representativeness of the data and the information on potential confounders and effect modifiers, including nativity, marital status, and WIC participation.

In a nationally representative sample of pregnant women, only 80 % lived in a fully food secure household. Among women with household incomes ≤300 % of the FPL, the average overall diet quality score reflects a need for improvement. Our study showed that food insecurity was not associated with overall diet quality among pregnant women with household incomes ≤300 % of the FPL in NHANES 1999–2008. Future research is needed to determine why the positive association between household food security and overall diet quality does not persist into pregnancy. As a substantial proportion of lower-income women are subject to household food insecurity during pregnancy and have diets of poor quality, a better understanding of the relationship between household food insecurity and overall diet quality is critical for improving population health of mothers and infants.

References

Adam, T. C., & Epel, E. S. (2007). Stress, eating and the reward system. Physiology & Behavior, 91(4), 449–458. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.04.011.

Black, A. P., Brimblecombe, J., Eyles, H., Morris, P., Vally, H., & Kerin, O. (2012). Food subsidy programs and the health and nutritional status of disadvantaged families in high income countries: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 12, 1099. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-1099.

Borders, A. E., Grobman, W. A., Amsden, L. B., & Holl, J. L. (2007). Chronic stress and low birth weight neonates in a low-income population of women. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 109(2 Pt 1), 331–338. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000250535.97920.b5.

Braveman, P., Marchi, K., Egerter, S., Kim, S., Metzler, M., Stancil, T., et al. (2010). Poverty, near-poverty, and hardship around the time of pregnancy. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 14(1), 20–35. doi:10.1007/s10995-008-0427-0.

Carmichael, S. L., Yang, W., Feldkamp, M. L., Munger, R. G., Siega-Riz, A. M., Botto, L. D., et al. (2011). Reduced risks of neural tube defects and orofacial clefts with higher diet quality. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine,. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.185.

Coleman-Jensen, C. G., & Singh, A. (2014). Household food security in the United States 2013. ERR-173, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

Cook, J. T., Black, M., Chilton, M., Cutts, D., de Cuba, S. E., Heeren, T. C., et al. (2013). Are food insecurity’s health impacts underestimated in the US population? Marginal food security also predicts adverse health outcomes in young US children and mothers. Advances in Nutrition: An International Review Journal, 4(1), 51–61.

Core indicators of nutritional state for difficult-to-sample populations. (1990). The Journal of nutrition, 120(Suppl 11), 1559–1600.

Curtin, S. C., Abma, J. C., Ventura, S. J., & Henshaw, S. (2013). Pregnancy rates for US women continue to drop. National Center for Health Statistics, Data Brief, 136, 1–8.

Elder, G. H, Jr., Johnson, M. K., & Crosnoe, R. (2003). The emergence and development of life course theory. Berlin: Springer.

Fowles, E. R., Bryant, M., Kim, S., Walker, L. O., Ruiz, R. J., Timmerman, G. M., et al. (2011). Predictors of dietary quality in low-income pregnant women: A path analysis. Nursing Research, 60(5), 286.

Fowles, E. R., Stang, J., Bryant, M., & Kim, S. (2012). Stress, depression, social support, and eating habits reduce diet quality in the first trimester in low-income women: A pilot study. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 112(10), 1619–1625.

Frongillo, E. A, Jr. (1999). Validation of measures of food insecurity and hunger. The Journal of nutrition, 129(2S Suppl), 506S–509S.

Gesteiro, E., Bernal, B. R., Bastida, S., & Sánchez-Muniz, F. (2012). Maternal diets with low healthy eating index or mediterranean diet adherence scores are associated with high cord-blood insulin levels and insulin resistance markers at birth. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 66(9), 1008–1015.

Harville, E. W., Schramm, M., Watt-Morse, M., Chantala, K., Anderson, J. J., & Hertz-Picciotto, I. (2004). Calcium intake during pregnancy among white and African-American pregnant women in the United States. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 23(1), 43–50.

Hoy, M. K., & Goldman, J. D. (2014). Calcium intake of the U.S. population: What we eat in America, NHANES 2009–2010. Food Surveys Research Group Dietary Data Brief No. 13. September 2014.

Hromi-Fiedler, A., Bermudez-Millan, A., Segura-Perez, S., & Perez-Escamilla, R. (2011). Household food insecurity is associated with depressive symptoms among low-income pregnant Latinas. Maternal & child nutrition, 7(4), 421–430. doi:10.1111/j.1740-8709.2010.00266.x.

Ivers, L. C., & Cullen, K. A. (2011). Food insecurity: Special considerations for women. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 94(6), 1740S–1744S. doi:10.3945/ajcn.111.012617.

Kendall, A., Olson, C. M., & Frongillo, E. A., Jr. (1996). Relationship of hunger and food insecurity to food availability and consumption. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 96(10):1019–1024; quiz 25–26. doi:10.1016/s0002-8223(96)00271-4.

King, J. C. (2003). The risk of maternal nutritional depletion and poor outcomes increases in early or closely spaced pregnancies. The Journal of nutrition, 133(5), 1732S–1736S.

Kreider, B., Pepper, J. V., & Roy, M. (2012). Identifying the effect of WIC on very low food security among infants and children. University of Kentucky Center for Poverty Research Discussion Paper Series. http://www.ukcpr.org/Publications/DP2012-11.pdf

Laraia, B. A. (2013). Food insecurity and chronic disease. Advances in Nutrition (Bethesda, Md), 4(2), 203–212. doi:10.3945/an.112.003277.

Laraia, B. A., Siega-Riz, A. M., & Gundersen, C. (2010). Household food insecurity is associated with self-reported pregravid weight status, gestational weight gain, and pregnancy complications. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 110(5), 692–701. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2010.02.014.

Laraia, B. A., Siega-Riz, A. M., Gundersen, C., & Dole, N. (2006). Psychosocial factors and socioeconomic indicators are associated with household food insecurity among pregnant women. The Journal of nutrition, 136(1), 177–182.

Looker, A. C., Loria, C. M., Carroll, M. D., McDowell, M. A., & Johnson, C. L. (1993). Calcium intakes of Mexican Americans, Cubans, Puerto Ricans, non-Hispanic whites, and non-Hispanic blacks in the United States. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 93(11), 1274–1279.

McIntyre, L., Glanville, N. T., Raine, K. D., Dayle, J. B., Anderson, B., & Battaglia, N. (2003). Do low-income lone mothers compromise their nutrition to feed their children? CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l’Association medicale canadienne, 168(6), 686–691.

NCHS Research Ethics Review Board Approval. (2014). http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/irba98.htm. Accessed July 25, 2014.

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics. Hyattsville (MD): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/tutorials/nhanes/surveydesign/Weighting/intro.htm. Accessed March, 2013.

Nord, M. (2010). Household food security in the United States (2008). Collingdale, PA: DIANE Publishing.

Olson, C. M., & Strawderman, M. S. (2003). Modifiable behavioral factors in a biopsychosocial model predict inadequate and excessive gestational weight gain. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 103(1), 48–54.

Pilgrim, A., Barker, M., Jackson, A., Ntani, G., Crozier, S., Inskip, H., et al. (2012). Does living in a food insecure household impact on the diets and body composition of young children? Findings from the Southampton Women’s Survey. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 66(6), e6. doi:10.1136/jech.2010.125476.

Poslusna, K., Ruprich, J., de Vries, J. H., Jakubikova, M., & van’t Veer, P. (2009). Misreporting of energy and micronutrient intake estimated by food records and 24 hour recalls, control and adjustment methods in practice. British Journal of Nutrition, 101(S2), S73–S85.

Rifas-Shiman, S. L., Rich-Edwards, J. W., Kleinman, K. P., Oken, E., & Gillman, M. W. (2009). Dietary quality during pregnancy varies by maternal characteristics in project viva: A US cohort. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 109(6), 1004–1011.

Robaina, K. A., & Martin, K. S. (2012). Food insecurity, poor diet quality, and obesity among food pantry participants in hartford, CT. Journal of nutrition education and behavior,. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2012.07.001.

Rodríguez-Bernal, C. L., Rebagliato, M., Iñiguez, C., Vioque, J., Navarrete-Muñoz, E. M., Murcia, M., et al. (2010). Diet quality in early pregnancy and its effects on fetal growth outcomes: The Infancia y Medio Ambiente (Childhood and Environment) Mother and Child Cohort Study in Spain. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 91(6), 1659–1666.

Rose, D., & Oliveira, V. (1997). Nutrient intakes of individuals from food-insufficient households in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 87(12), 1956–1961.

Rothman, K. J., Greenland, S., & Lash, T. L. (2008). Modern epidemiology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Tarasuk, V. S., & Beaton, G. H. (1999). Women’s dietary intakes in the context of household food insecurity. The Journal of nutrition, 129(3), 672–679.

Thomas, M., & Weisman, S. M. (2006). Calcium supplementation during pregnancy and lactation: Effects on the mother and the fetus. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 194(4), 937–945.

Watts, V., Rockett, H., Baer, H., Leppert, J., & Colditz, G. (2007). Assessing diet quality in a population of low-income pregnant women: A comparison between Native Americans and whites. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 11(2), 127–136. doi:10.1007/s10995-006-0155-2.

Willett, W. (2013). Nutritional epidemiology (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

California Department of Public Health. (2014). Women, infants and children supplemental nutrition. http://www.cdph.ca.gov/PROGRAMS/CENTERFORFAMILYHEALTH/Pages/WICFactSheet.aspx. Accessed April, 2014.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

R. Gamba, C. Leung, S. Guendelman, M. Lahiff, B. Laraia have no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gamba, R., Leung, C.W., Guendelman, S. et al. Household Food Insecurity Is Not Associated with Overall Diet Quality Among Pregnant Women in NHANES 1999–2008. Matern Child Health J 20, 2348–2356 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-016-2058-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-016-2058-1