Abstract

Objectives The United States Department of Agriculture’s Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) provides meals and snacks to low-income children in child care. This study compared nutrition and physical activity practices and policies as well as the overall nutrition and physical activity environments in a sample of CACFP and non-CACFP child care settings. Methods A random stratified sample of 350 child care settings in a large Midwestern city and its suburbs, was mailed a survey on obesity prevention practices and policies concerning menu offerings, feeding practices, nutrition and physical activity education, activity levels, training, and screen time. Completed surveys were obtained from 229 of 309 eligible child care settings (74.1 % response rate). Chi square tests were used to compare practices and policies in CACFP and non-CACFP sites. Poisson and negative binomial regression were used to examine associations between CACFP and total number of practices and policies. Results Sixty-nine percent of child care settings reported CACFP participation. A significantly higher proportion of CACFP sites reported offering whole grain foods daily and that providers always eat the same foods that are offered to the children. CACFP sites had 1.1 times as many supportive nutrition practices as non-CACFP sites. CACFP participation was not associated with written policies or physical activity practices. Conclusions for Practice There is room for improvement across nutrition and physical activity practices and policies. In addition to food reimbursement, CACFP participation may help promote child care environments that support healthy nutrition; however, additional training and education outreach activities may be needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Significance

This is one of the first studies to examine how Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) participation may influence a range of obesity prevention activities, including the presence of nutrition and physical activity related written policies, in a variety of child care settings. Benefits of CACFP may extend beyond food reimbursement. In this study, participation in CACFP was associated with a greater number of total supportive nutrition practices in child care settings.

Introduction

Child care settings, where preschool children spend an average of 28 h per week [1] and consume half to three quarters of their daily energy [2], have become the focus of several childhood obesity prevention efforts [3, 4]. More than two-thirds of preschool children are enrolled in non-parental care including centers and family child care homes [1]. Although child care settings have multiple opportunities to support healthy eating and active play in children, some studies have found poor nutritional quality of foods served [5, 6] and inadequate physical activity among children [7, 8] in child care. With the exception of Head Start programs, which are federally required to meet program performance nutrition and physical activity standards [9], there are no federal regulations for nutrition and physical activity in child care settings [4]; meanwhile, state regulations have been weak [10].

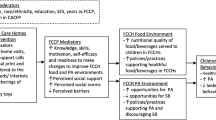

The United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP), which is a federal nutrition assistance program that provides reimbursement for meals and snacks for low-income children in participating child care programs, may contribute to an overall child care environment that promotes healthy behaviors [11]. To qualify for reimbursement, meals and snacks are required to include a minimum number of age-appropriate servings of vegetables, fruits or 100 % fruit juice; grains or bread; meat or meat alternates; and fluid milk [11]. Although a recent study found that lunch served in CACFP centers were not consistent with the 2011 Institute of Medicine recommendations for saturated fat, protein, fiber, and sodium [12], CACFP participation has been associated with increased consumption of milk and vegetables [13, 14] and reduced consumption of sweets [14] in children. In CACFP family child care homes, higher nutritional quality of foods served was associated with higher reimbursements rates [15].

CACFP may also contribute to an overall child care environment that promotes the development of healthy eating and physical activity behaviors. CACFP requires annual nutrition training for participating staff and facilities, provides periodic monitoring of menus, and conducts regular site visits [16]. CACFP has also provided guidelines on fostering a supportive feeding environment, including allowing children to serve themselves [17]. In 2010, Congress passed the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act (HHFKA), which called for CACFP sites to offer daily opportunities for physical activity and limit screen-time and directed USDA to provide training and technical assistance on nutrition and wellness [18]. However, little is known about physical activity practices and policies in CACFP and non-CACFP sites pre-HHFKA implementation.

The purpose of this study was to compare nutrition and physical activity practices and policies as well as the overall nutrition and physical activity environments in CACFP and non-CACFP sites. We hypothesized that CACFP sites, because of program requirements, would have a greater number of supportive nutrition practices and policies than non-CACFP sites. Furthermore, we hypothesized that the number of physical activity practices and policies would be similar in CACFP and non-CACFP sites pre-HHFKA implementation. A secondary objective was to examine whether there were differences in nutrition and physical activity practices and policies between centers and family child care homes.

Methods

Sample

The study population was licensed centers and family child care homes in a large Midwestern city and its suburbs [19]. Using a publicly available state database of licensed child care settings (n = 587) as of March 2011, a stratified random sample of 175 centers and 175 family child care homes in a Midwest metropolitan area was selected. Stratified random sampling was used to ensure an adequate sample of both centers and family child care homes in the study. Of the 350 sampled child care settings, 41 were ineligible (e.g., undeliverable, permanently closed). Completed surveys were obtained from 229 child care settings, resulting in a response rate of 74.1 %. This analysis focused on full-day child care settings serving preschool children ages 3–5 years (n = 198). Head Start centers (n = 9), which are subject to federal nutrition and physical activity regulations, and child care settings where children bring meals from home (n = 13) were excluded, resulting in an analytic sample of 185.

Procedures

Data for this descriptive cross-sectional survey were collected from May to July 2011. Sampled child care settings were mailed a survey about general characteristics of the child care facility, opportunities for physical activity; available play equipment; the types of food served; and staff/provider practices and policies related to nutrition and physical activity (see Appendix of ESM). The survey took approximately 20-min to complete. Survey questions were pretested with child care providers using cognitive interviewing techniques and evaluated for face and content validity by academic experts in survey design and local CACFP sponsoring organizations; modifications were made to the wording of select survey questions and response options as well as to the survey layout based on pre-testing feedback. Survey mailings were addressed to the center administrator and family child care provider. Starting approximately 2–3 days after survey mailings, up to 3 phone calls attempts were made to confirm receipt of the survey and schedule in-person survey pick-up. Up to 3 in-person survey pick-up attempts were made for each child care setting on various days of the week and times of day in efforts to reduce response bias. Participants received a $10 gift card for completing the survey. This study was determined to be exempt by the university’s Institutional Review Board.

Measures

CACFP Participation

Participants were asked whether they are “actively involved,” “getting involved,” “previously involved but not currently,” or “not involved” in CACFP. Responses of “actively involved” were categorized as participating in CACFP and “getting involved,” “previously involved but not currently,” and “not involved” were categorized as non-CACFP.

Obesity Prevention Practices and Policies

This analysis focused on 14 nutrition practices, 11 written nutrition policies, 4 physical activity practices, and 3 written physical activity policies. The nutrition and physical activity practices and policies examined were based on the “Caring for Our Children: National Health and Safety Performance Standards: Guidelines for Early Care and Education Programs, 3rd edition” [20] and the National Association for Sport and Physical Education, 2nd edition [21]. Survey questions were modified from The Nutrition and Physical Activity Self-Assessment for Child Care [22], and the Environment and Policy Assessment and Observation instrument [23] to fit the needs of the local health department. Participants were asked about their daily menu offerings; provider role modeling practices; family style meals; nutrition and physical activity education; physical activity levels; screen time; staff training; and policies on beverages, child feeding, use of food, screen time, and physical activity (see Appendix of ESM). Survey responses were dichotomized to indicate the presence and absence of a supportive practice or written policy. Responses of “don’t know” or missing were coded as absence of a supportive practice or written policy. To characterize the overall nutrition and physical activity environments, we calculated the total number of supportive nutrition practices, total number of supportive nutrition policies, total number of supportive physical activity practices, and total number of physical activity policies.

Data Analysis

Chi square tests were used to compare nutrition and physical activity practices and policies in CACFP and non-CACFP sites. Poisson regression models were used to examine the association between CACFP participation and the total number of practices for nutrition and physical activity, respectively. Because of overdispersion in the response variables, negative binomial regression models were used to examine the association between CACFP participation and the total number of policies for nutrition and physical activity, respectively. An alpha level of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance. Analyses were conducted using the Statistical Analysis Software (version 9.1.3, 2006, SAS Institute Inc.).

Results

Sample Characteristics

Overall, 69 % of the 185 child care settings reported CACFP participation. Fifty-six percent of the child care settings were centers, 44 % were family child care homes, 65 % were located in the city, and 43 % participated in early childhood care and education programs. There were no differences in type of child care, geographic region, relative size of facility, provider education level, and participation in childhood care and education programs between CACFP and non-CACFP sites. Of CACFP sites, 94 % participated in Title XX, a subsidy program that provides low-income working parents financial assistance for child care compared to 78 % of non-CACFP sites (p = 0.003).

Nutrition Practices and Written Policies in CACFP and Non-CACFP Sites

We found significant differences between CACFP and non-CACFP sites for 2 of the 14 nutrition practices (Table 1). A higher proportion of CACFP sites reported offering whole grain foods every day (61 vs. 43 %), and a higher proportion of CACFP sites reported that staff/providers always eat the same foods that are offered to the children (53 vs. 35 %). The overwhelming majority of CACFP and non-CACFP sites reported offering vegetables every day and fruits every day. However, more than half of CACFP and non-CACFP sites reported offering breaded foods at least once a week and that staff/providers drink soda, pop, sports drinks, and sugar sweetened beverages in front of the children. CACFP sites had a median of 8 total supportive nutrition practices compared to a median of 7 total supportive nutrition practices in non-CACFP sites. CACFP participation was significantly associated with the total number of supportive nutrition practices (β = 0.13, SE = 0.06, p = 0.03); CACFP sites had 1.1 times as many supportive nutrition practices as non-CACFP sites.

No significant differences between CACFP and non-CACFP sites were observed across the 11 written nutrition policies. Policies that only milk, water, and 100 % fruit juice are served, providers cannot withhold or delay food or drinks as punishment, and providers cannot force children to eat certain amounts of food were the most common nutrition policies in CACFP and non-CACFP sites; having a written policy that meals are served family-style and providers cannot eat or drink food from outside in front of the children were the least common nutrition policies. Both CACFP and non-CACFP sites had a median of 4 total supportive nutrition policies; CACFP participation was not associated with the total number of supportive nutrition policies (β = 0.12, SE = 0.15, p = 0.44).

Physical Activity Practices and Written Policies in CACFP and Non-CACFP Sites

No significant differences were observed between CACFP and non-CACFP sites in terms of physical activity practices and written policies (Table 1). In both CACFP and non-CACFP sites, adult-led physical activity for at least 60 min was the least common physical activity practice. Displaying physical activity posters, books, or pictures was the most prevalent physical activity practice among CACFP sites whereas preschoolers engaging in ≥60 min of free play each day was the most common among non-CACFP sites. Only half of CACFP and non-CACFP sites reported having a written policy that children are required to engage in 60 min of free play. Both CACFP and non-CACFP sites had a median of 2 supportive physical activity practices and 1 physical activity policy; CACFP participation was not associated with the total number of supportive practices (β = −0.01, SE = 0.11, p = 0.95) or the total number of policies (β = 0.02, SE = 0.15, p = 0.88) for physical activity.

Comparison of Practices and Policies in Centers and Family Child Care Homes

We found significant differences between centers and family child care homes for 2 nutrition practices and 2 physical activity practices. A higher proportion of centers reported not offering fried foods (59 vs. 38 %, p = 0.001) while a higher proportion of family child care homes reported teaching children about the food groups at least once a month (44 vs. 27 %, p = 0.01). A higher proportion of family child care homes compared to centers reported that preschoolers engage in ≥60 min of adult-led physical activity each day (33 vs. 18 %, p = 0.02), and that they require training on how to help children be physically active (78 vs. 56 %, p = 0.002).

Significant differences between centers and family child care homes were noted for 9 of the 11 nutrition policies. Specifically, a higher proportion of centers had policies that only milk, water, and 100 % fruit juice are served to the children (77 vs. 47 %, p < 0.001); <6 oz of 100 % fruit juice per day are served to children 12 months of age and older (43 vs. 22 %, p = 0.003); skim, 1 or 2 % milk are served to children older than 2 years of age (50 vs. 28 %, p = 0.003); providers cannot eat or drink food from outside in front of the children (31 vs. 12 %, p = 0.003); providers cannot withhold/delay food or drinks as a punishment (83 vs. 44 %, p < 0.001); providers cannot give food or drinks as a reward or an incentive (48 vs. 30 %, p = 0.01); providers cannot force children to eat certain foods or certain amounts of food (55 vs. 33 %, p = 0.004); providers allow children to decide how much to eat (38 vs. 25 %, p = 0.05); and each child is to be encouraged but not forced to eat or taste his or her food (45 vs. 30 %, p = 0.03).

Discussion

Within current regulations and practices, participation in CACFP provides a basic nutritional safety net for low-income children and may contribute to a healthy child care environment. Study findings confirmed our hypothesis that CACFP participation was significantly associated with a greater total number of supportive nutrition practices.

CACFP and non-CACFP sites had menus with similar offerings of fruits, vegetables, fried, and breaded foods; however, a higher proportion of CACFP sites in the study had menus that offered whole grain foods every day than non-CACFP sites. Under the current USDA meal pattern for CACFP, whole grains are encouraged but are not required to be a part of meals or snacks [16]. CACFP also provides menu suggestions; resource materials for menus, recipes, and meal planning; and periodic monitoring of menus, which may further explain the higher prevalence of whole grain foods offered in CACFP sites [17, 24]. The 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommends that children consume at least half of their daily grain intake as whole grains [25].

In addition to annual training on nutrition and meal pattern requirements, CACFP also provides guidelines on fostering a supportive feeding environment, including allowing children to serve themselves [17]. Family-style meals were more common in CACFP but not statistically different than non-CACFP sites. However, more CACFP sites reported that staff/providers always eat the same foods that the children are offered. Providers eating the same foods offered to children have been suggested as a way to strengthen family-style eating and support children serving and feeding themselves [26]. During CACFP site reviews, which are conducted three times a year at participating family child care homes and at least once every 3 years at participating centers, CACFP monitors can use a variety of assessment tools and train facilities to use these tools to improve nutrition practices [27].

Overall, our findings complement previous reports of supportive nutrition environment in CACFP sites [27, 28]. Sigman-Grant et al. found that CACFP centers in four states more frequently used family-style meal service, had providers sit at the table with the children, talked about the food at mealtimes, and strongly disagreed that “if children put food on their plate, they should eat it” than non-CACFP centers. Sigman-Grant and colleagues found that presence of a supportive nutrition environment was partly explained by materials or trainings through CACFP [27].

In the study, CACFP and non-CACFP sites reported similar physical activity practices, confirming our hypothesis. Physical activity was not part of CACFP requirements at the time of this study. Provisions of the HHFKA, which are still in the process of being implemented, called for child care providers to offer daily opportunities for structured and unstructured physical activity and limit screen-time in child care [18]. USDA was also directed to provide nutrition and wellness education and training on best-practices for physical activity.

This is one of the first studies to examine the presence of written nutrition-related policies in CACFP and non-CACFP sites. Written or formal policies set clear standards and expectations about behaviors and may contribute to an environment that promotes healthy behaviors in children [29, 30]. Although the prevalence of nutrition policies in CACFP and non-CACFP sites was similar, we found that an overwhelming majority of the nutrition policies about beverages served, child feeding, and use of food studied were more common in centers than family child care homes. Formal policies may be more common in centers than family child care homes since centers typically have more than one staff member/child care provider whereas family child care homes consist of one child care provider. To our knowledge, no study has directly compared nutrition and physical activity practices and/or policies in child care centers and family child care homes. Since child care centers and family child care homes in the study are both licensed programs through state and federal requirements and monitored by the state for compliance, we did not expect differences in nutrition and physical activity practices.

There are limitations to this study. Data were self-reported, which may have resulted in response bias. Efforts to reduce socially desirable responses were made by using a mail self-administered survey and reminding providers that responses would not be shared with licensing agencies. In most cases, the survey for child care centers were completed by the director or assistant director, which may not reflect current child care practices in the facility or knowledge of written policies. Since only licensed child care programs in a Midwest metropolitan area were included in the sampling frame, findings may not be generalizable to providers in other regions. Furthermore, this study, which did not examine whether menus meet nutrient-based standards or collect children’s nutritional intake, only provides a basic overview of the quality of meals offered. Best-practices examined in this study were based on the “Caring for Our Children: National Health and Safety Performance Standards: Guidelines for Early Care and Education Programs, 3rd edition” [20] and the National Association for Sport and Physical Education, 2nd edition [21], which may not reflect 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Although some time has passed since the data for this study was collected, the early childhood policy landscape has not significantly changed. Although the HHFKA was passed by Congress in 2010, provisions concerning CACFP (Section 221), which address nutrition and wellness goals for meals served through CACFP, and call for technical assistance to be provided to participating CACFP institutions to meet nutrition requirements and wellness recommendations for active play and screen time, are still in the process of being implemented [18]. Lastly, these analyses are cross-sectional and do not provide evidence of causality. Despite these limitations, this study provides an overall assessment of the nutrition and physical activity environment in CACFP and non-CACFP sites, including family child care homes. Several of the practices and formal policies examined have not been previously studied in both centers and family child care homes.

CACFP participation has the potential to contribute to a healthy weight in children. These findings provide evidence that while meal and snack reimbursement is the primary focus of CACFP, a supportive nutrition environment is also promoted in CACFP sites through existing infrastructure. However, as this study found, there is still room for improvement across nutrition and physical activity practices and policies in CACFP and non-CACFP sites. Implementation of provisions in the HHFKA has the potential to further improve the nutrition and physical activity environments in CACFP sites and may contribute to greater differences between CACFP and non-CACFP sites. Child care programs eligible for CACFP should be encouraged to enroll since the benefits may go beyond food reimbursement. CACFP program requirements and training materials can serve as a guide for other child care programs not eligible for CACFP.

References

U.S. Department of Education. (2006). Early Childhood Program Participation Survey of the National Household Education Surveys Program (ECPP-NHES: 2005). Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d09/tables/dt09_044.asp.

Benjamin Neelon, S. E., Briley, M. E., & American Dietetic Association. (2011). Position of the American Dietetic Association: Benchmarks for nutrition in child care. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 111(4), 607–615.

Larson, N. I., Ward, D. S., Neelon, S. B., & Story, M. (2011). What role can child-care settings play in obesity prevention? A review of the evidence and call for research efforts. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 111(9), 1343–1362.

Story, M., Kaphingst, K. M., & French, S. (2006). The role of child care settings in obesity prevention. The Future of Children, 16(1), 143–168.

Erinosho, T. O., Ball, S. C., Hanson, P. P., Vaughn, A. E., & Ward, D. S. (2013). Assessing foods offered to children at child-care centers using the healthy eating index-2005. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 113(8), 1084–1089.

Ball, S. C., Benjamin, S. E., & Ward, D. S. (2008). Dietary intakes in North Carolina child-care centers: Are children meeting current recommendations? Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 108(4), 718–721.

Reilly, J. J. (2010). Low levels of objectively measured physical activity in preschoolers in child care. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 42(3), 502–507.

Pate, R. R., McIver, K., Dowda, M., Brown, W. H., & Addy, C. (2008). Directly observed physical activity levels in preschool children. Journal of School Health, 78(8), 438–444.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2008). Head Start program performance standards and other regulations. Retrieved from http://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/hslc/standards/Head%20Start%20Requirements/.

Benjamin, S. E., Cradock, A., Walker, E. M., Slining, M., & Gillman, M. W. (2008). Obesity prevention in child care: A review of U.S. state regulations. BMC Public Health, 8(188), 1–10.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2013). Child and Adult Care Food Program. Retrieved from http://www.fns.usda.gov/cnd/care/CACFP/aboutcacfp.htm.

Schwartz, M. B., Henderson, K. E., Grode, G., Hyary, M., Kenney, E. L., O’Connell, M., et al. (2015). Comparing current practice to recommendations for the Child and Adult Care Food Program. Childhood Obesity, 11(5), 491–498.

Korenman, S., Abner, K. S., Kaestner, R., & Gordon, R. A. (2013). The Child and Adult Care Food Program and the nutrition of preschoolers. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28(2), 325–336.

Ritchie, L. D., Boyle, M., Chandran, K., et al. (2012). Participation in the Child and Adult Care Food Program is associated with more nutritious foods and beverages in child care. Childhood Obesity, 8(3), 224–229.

Monsivais, P., Kirkpatrick, S., & Johnson, D. B. (2011). More nutritious food is served in child-care homes receiving higher federal food subsidies. Journal of American Dietetic Association, 111(5), 721–726.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2013). CACFP regulations. Retrieved from http://www.fns.usda.gov/cnd/care/regs-policy/regulations.htm.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2014). Child and Adult Care Food Program. Retrieved from http://www.fns.usda.gov/cacfp/cacfp-handbooks.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2013). Summary of the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010. Retrieved from http://www.fns.usda.gov/cnd/governance/legislation/PL111-296_Summary.pdf.

Ohio Department of Jobs and Family Services. (2011). Child day care. Retrieved from http://www.odjfs.state.oh.us/cdc/query.asp.

American Academy of Pediatrics, American Public Health Association, National Resource Center for Health and Safety in Child Care and Early Education. (2011). Caring for Our Children: National Health and Safety Performance Standards; Guidelines for Early Care and Education Programs (3rd ed.). Elk Grove Village, IL; Washington, DC: American Academy of Pediatrics; American Public Health Association.

National Association for Sport and Physical Education. (2013). Active start: A statement of physical activity guidelines for children from birth to age 5 (2nd ed.). Retrieved from http://www.aahperd.org/naspe/standards/nationalGuidelines/ActiveStart.cfm.

Ammerman, A. S., Ward, D. S., Benjamin, S. E., Ball, S. C., Sommers, J. K., Molloy, M., et al. (2007). An intervention to promote healthy weight: Nutrition and physical activity self-assessment for child care (NAP SACC) theory and design. Preventing Chronic Disease, 4(3), A67.

Ward, D., Hales, D., Haverly, K., Marks, J., Benjamin, S., Ball, S., et al. (2008). An instrument to assess the obesogenic environment of child care centers. American Journal of Health Behavior, 32(4), 380–386.

Children’s Hunger Alliance. (2013). Child care provider resources. Retrieved from http://www.childrenshungeralliance.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=cms.page&id=1038.

U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2010). Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Dietz, W., & Birch, L. (2008). Eating behaviors of young child: Prenatal and postnatal influences on healthy eating. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics.

Sigman-Grant, M., Christiansen, E., Fernandez, G., Fletcher, J., Johnson, S. L., Branen, L., et al. (2011). Child care provider training and a supportive feeding environment in child care settings in 4 states, 2003. Preventing Chronic Disease, 8(5), A113.

Dev, D. A., McBride, B. A., & The STRONG Kids Research Team. (2013). Academy of nutrition and dietetics benchmarks for nutrition in child care 2011: Are child-care providers across contexts meeting recommendations? Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 111(10), 1346–1353.

Erinosho, T. O., Hales, D. P., McWilliams, C. P., Emunah, J., & Ward, D. S. (2012). Nutrition policies at child-care centers and impact on role modeling of healthy eating behaviors of caregivers. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 112(1), 119–124.

Story, M., Kaphingst, K. M., Robinson-O’Brien, R., & Glanz, K. (2008). Creating healthy food and eating environments: Policy and environmental approaches. Annual Review of Public Health, 29, 253–272.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Cooperative Agreement No. U48-DP001912 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The findings and conclusions in this journal article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

At the time of this study, Sherry T. Liu was affiliated with The Ohio State University College of Public Health, Columbus, OH. Dr. Liu is now with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, College Park, MD.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, S.T., Graffagino, C.L., Leser, K.A. et al. Obesity Prevention Practices and Policies in Child Care Settings Enrolled and Not Enrolled in the Child and Adult Care Food Program. Matern Child Health J 20, 1933–1939 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-016-2007-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-016-2007-z