Abstract

Objectives Healthcare providers in low-resource settings confront high rates of perinatal mortality. How providers cope with such challenges can affect their well-being and patient care; we therefore sought to understand how physicians and midwives make sense of and cope with these deaths. Methods We conducted semi-structured interviews with midwives, obstetrician-gynecologists, pediatricians and trainee physicians at a large teaching hospital in Kumasi, Ghana. Interviews focused on participants’ coping strategies surrounding perinatal death. We identified themes from interview transcripts using qualitative content analysis. Results Thirty-six participants completed the study. Themes from the transcripts revealed a continuum of control/self-efficacy and engagement with the deaths. Providers demonstrated a commitment to push on with their work and provide the best care possible. In select cases, they described the transformative power of attitude and sought to be agents of change. Conclusions Physicians and midwives in a low-resource country in sub-Saharan Africa showed remarkable resiliency in coping with perinatal death. Still, future work should focus on training clinicians in coping and strengthening their self-efficacy and engagement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Significance

What is already known on this subject? Healthcare providers in low-resource settings confront high rates of perinatal mortality. Stillbirths and infant deaths have been shown to be stressful and traumatic for physicians and midwives, with the majority of this research coming from high-income countries.

What this study adds? This qualitative analysis of how healthcare providers working in one resource-poor setting make sense of and cope with high rates of perinatal death. Providers’ responses to stillbirths and infant deaths spanned a spectrum from focusing on systemic issues that were beyond their control to emphasizing their self-efficacy. Coping mechanisms were most notable for a commitment to pushing on and providing the best care possible.

Introduction

Healthcare providers’ experiences with their patients’ deaths can significantly impact their well-being, empathy, and patient care. Stillbirths and infant deaths can be particularly challenging, and have been shown to be stressful and traumatic for physicians, midwives and nurses [1–5]. However, the majority of this research is from high-income countries where these deaths occur relatively infrequently. In low-resource settings such as sub-Saharan Africa, clinicians face far more frequent deaths. This burden of death typically occurs in settings with limited staff, minimal resources, and heavy patient loads, making it more difficult for providers to have time, backup (other staff to help with their work) or other support to cope. Studies from low-resource settings have documented emergency healthcare providers’ emotional distress surrounding death, including feelings of blame and having to reject their emotions. These providers noted particular struggles with pediatric deaths, which felt unnatural and exceptionally tragic, as well as in situations where they were unable to grieve previous losses [6]. A South African study documented high levels of burnout among hospice workers, attributed both to the nature of working with dying patients as well as various other work-related stressors [7].

While multifaceted efforts continue to reduce the global burden of perinatal mortality [8], attention must be paid to the well-being of clinicians who face these deaths on a daily basis. Thus, it is pertinent to ask how they are affected by high rates of perinatal death. Coping theory research suggests that stress results when the demands on an individual exceed the ability to cope [9]. Extensive research on coping method classifications exists, with pioneering work demonstrating that individuals often employ multiple coping strategies for a single stressor [9]. Bandura’s theory of self-efficacy suggests that effort in coping is related to a sense of personal mastery, and that individuals will avoid difficult experiences if they do not feel they have adequate skills to manage them. Similarly, self-efficacy can predict how well and how long individuals can cope in the face of grave challenges [10]. Latack described a demarcation between coping styles with control/proactive orientations versus escapist/avoidance orientations, but also recognized other categorizations including solitary/social and cognitive/behavioral. Control/proactive orientations include taking action on a problem or positive thinking, whereas escapist/avoidance orientations can involve staying away from a stressor or trying not to worry about it [11]. Others have used Latack’s classifications and found that control-oriented strategies led to lower levels of burnout and emotional exhaustion than avoidance strategies [12]. The limited research on healthcare provider coping with death in low-resource settings has documented that healthcare workers generally benefit from support from colleagues, but require further resources and training to adequately cope [13, 14].

We identified no studies on how healthcare workers in low-resource countries cope with high levels of perinatal death, which is known to raise unique challenges. These include these deaths’ often sudden and unexpected nature, the simultaneous and seemingly incongruent occurrence of birth and death, the lack of control which health providers may feel, the frequent absence of an apparent cause, and in some countries, the associated medical-legal issues [5]. We therefore performed an exploratory qualitative content analysis study to determine how healthcare providers working in one such country make sense of and cope with high rates of perinatal death.

Methods

We interviewed clinicians at Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital (KATH) in Kumasi, Ghana. KATH is a tertiary referral hospital with roughly 14,000 deliveries, 500 stillbirths, and over 900 neonatal deaths per year [15]. Historically, mortality in the newborn unit was about 20 % [unpublished data]. Thus, providers in obstetrical and pediatric units are likely to face high levels of death.

Obstetrician-gynecologists, pediatricians, midwives and trainee physicians on the obstetrical and newborn units were selected as subjects since they were most likely to have frequent experiences with perinatal death. Deliveries are typically staffed by obstetrician–gynecologists or midwives, and the neonatal ward is staffed by both junior and senior pediatricians. House officers are physicians who are completing 2 years of general training, which includes 6 months each in pediatrics and obstetrics–gynecology. Residents are physicians completing 3 years of additional training in a given field, and specialists have completed their training. Perinatal death was defined as a death occurring between 28 weeks gestation (stated or presumed) through the first 28 days of age. Healthcare providers in Ghana are trained in English, enabling us to conduct interviews in English. All participants were age 18 or older. Interviews occurred in two discrete periods (June–July of 2011 and 2012) during separate research trips to Ghana.

This research built on a longstanding collaborative relationship between KATH and the University of Michigan, and key contacts at KATH endorsed the study. Capacity-building occurred in a broader context, including assistance in the establishment of residency programs at KATH, research training and collaborations (outside of this study), and bilateral exchange of trainees and faculty.

The number of subjects was determined based on being likely to both obtain a diversity of views from different specialties and achieve thematic saturation. Potential participants were identified through staff registries, and those with availability and interest were invited to participate. We used snowball sampling to identify subsequent subjects using purposeful efforts to obtain as broad a diversity as possible of specialties, levels of training and experience, and gender. Demographic diversity was to some extent limited by the baseline characteristics of these departments. Selection was also made based on participants’ anticipated availability, and previous participants’ recommendations of who would offer helpful perspectives. Participants were approached in person or via telephone. No provider declined to participate but a small number (<5) were unavailable. Interviews occurred in private rooms in the hospital or medical school; the 1–2 interviewers and interviewee were the only people present, except in a few cases where interviewees explicitly allowed the presence of a non-participant colleague.

After giving verbal informed consent, subjects provided demographic information and completed a written survey mirroring a similar study with U.S. physicians [5]. Except for the demographic data, information from these surveys is not presented here as it was felt this manuscript was most cohesive looking only at the qualitative interviews. Eight pre-clinical, second-year University of Michigan medical students (including one of the authors), of whom seven were female, served as interviewers. They were trained in qualitative interviewing techniques and conducted individual semi-structured interviews lasting on average 30 min. These addressed the causes and emotional impacts of perinatal death and providers’ coping strategies, plus additional questions as part of a larger study (Supplementary Material S1). Interviewers had minimal contact with participants outside the interviews. Participants were offered an incentive worth about $3, and each participant was interviewed once. The distribution of specialties (though relatively even over the 2 years) included more pediatricians in the first year and more obstetrician–gynecologists in the second. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Written field notes documented the tone and other noteworthy characteristics of the interview. As data analysis occurred after data collection was completed, reflexivity to ensure complete thematic saturation was not possible. Participants did not review their transcripts or provide feedback after data collection.

Following the completion of all interviews, two reviewers (A.D.P. and K.J.G.) read the anonymized transcripts and identified themes that emerged. After multiple iterations, these were organized into nine discrete themes. Reviewers coded the transcripts with these nine themes, and individual discordances were resolved through consensus. To connect this study to the larger body of coping research, existing literature was reviewed (described in the “Introduction” and “Discussion” sections) and found to be consistent with the themes. The themes from our respondents showed varying levels of control/self-efficacy—the practitioner’s ability to do something about the death—and engagement, defined as the provider’s tendency to process and think about the death. The concept of control/self-efficacy was derived directly from participants’ words, and includes elements both of being able to cope with a situation as well as ability to modify the situation itself. This reflects the concept of self-efficacy articulated by both Bandura and Latack [10, 11]. We organized the themes along a continuum of increasing control/self-efficacy and engagement, here presented as ‘low,’ ‘moderate’ and ‘high.’ In ‘low’ themes providers felt limited control over deaths and their ability to respond, with minimal acknowledgment of an emotional response; in ‘high’ themes, clinicians took action in response to deaths, and engaged more deeply with the emotional implications on themselves and others.

The study received human subjects approval from the Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan and the Committee on Human Research Publication and Ethics of the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in Kumasi, Ghana.

Results

Thirty-six healthcare providers participated in the study, including 10 midwives, 13 obstetrician-gynecologists (including trainees) and 13 pediatricians (including trainees). The cohort included 21 females (58 %) and 15 males (42 %). The average time in practice was 7 years, with a range of 4 months–28 years (Table 1).

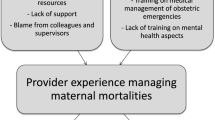

Nine themes emerged from the interview transcripts, including coping mechanisms—things that participants did when faced with a stressor—as well as various ways they thought about perinatal deaths. The latter were key to how providers made sense of these deaths, and especially whether they had a role in causing them. On the spectrum of control/self-efficacy and engagement, ‘low’ themes included statements on systemic issues that participants characterized as beyond the influence of the individual clinician; in ‘high’ themes, providers recognized their ability to be agents of change and demonstrated emotional engagement with the death (Fig. 1). For the interview themes, no noteworthy differences in response patterns across specialties were observed. Each respondent was noted to have responses in more than one of the themes, suggesting they coped in multiple ways.

Low Control/Self-Efficacy and Engagement Themes

Low control/self-efficacy and engagement themes (Table 2) included statements on (1) “resources and system issues” causing deaths; (2) perinatal death being an “unexplainable reality of life”; (3) providers trying to “forget about” or “being cold” towards the death; and (4) stating that the death was “not my fault.” In these responses, clinicians focused on factors in the external world. When asked how they coped, 15 (42 %) responded that perinatal deaths are caused by resource and systems issues that—though preventable—are beyond their control. For example, they cited staffing levels, facilities, and medical equipment as inadequate for their heavy patient load, and patients being referred from outside hospitals too late. Eight providers (22 %) stated that some perinatal deaths are an inevitable reality of life, or are unexplainable and must be left to God. The fact that providers responded in this way when asked how they coped suggests that such concepts were important to how they made sense of these deaths.

Nineteen participants (53 %) reported trying not to think about the deaths, or distancing themselves emotionally. Some commented that the high volume of deaths requires a degree of detachment, and actively distanced themselves; others were frustrated with not having time to grieve, and felt that “being cold” was problematic. Seven providers (19 %) did not assign blame for the death but only stated that it was not their fault. For some, knowing that they could not have done anything to save the baby lessened the emotional impact.

Moderate Control/Self-Efficacy and Engagement Themes

In themes reflecting moderate control/self-efficacy and engagement (Table 3), participants (5) conveyed the need to “just keep going” and accepted perinatal death as “part of the job”; (6) acknowledged the “emotional impact” of the death; and (7) employed “active coping” strategies including talking with others. Here they seemed to focus their attention more internally onto things they could control. Both when asked how they coped with a death and how they went on to their next patient, 22 providers (61 %) replied that they just keep going. While descriptions of “moving on” also existed in the “forget about it/being cold” theme, here participants displayed greater acceptance of the need to keep going. They stated that in this environment, encountering perinatal death was a reality of their work.

Twenty-six providers (72 %) reported substantial emotional impacts from perinatal deaths, including trauma, stress, pain, sadness and sharing in the mother’s grief. Twenty-six participants (72 %) also described active coping mechanisms including talking about the death with colleagues, family, or friends, which they found helpful. Some shared their grief with the patient’s family, prayed, or took time for themselves before caring for their next patient. These themes demonstrate moderate control/self-efficacy—providers taking some action related to the death—and moderate engagement, as they recognized and processed their emotions.

High Control/Self-Efficacy and Engagement Themes

In high control/self-efficacy and engagement themes (Table 4), clinicians sought to “find a cause” for the death and “do my best”; they also conveyed a fuller understanding of their patients and the power of attitude. The most frequent coping strategy by far—endorsed by 33 participants (92 %)—was striving to provide the best care possible. Providers coped with a death by reviewing the case and their management of it, trying to determine its cause, and then becoming more vigilant to prevent future losses. These activities reflect substantial self-efficacy, as providers focused on their management and how to prevent such deaths in the future.

Finally, nine participants (25 %) were driven to continue with their work by a deeper sense of purpose. They reported an intense awareness of their patients’ pain and suffering, which often related to recognizing the gravity of perinatal loss and its impacts on families. Some noted that healthcare workers often feel overwhelmed by systemic issues but with a different attitude can control more than they think, a direct contrast to statements deferring to systemic issues. This enhanced understanding of patients’ lives demonstrates the highest level of engagement, as clinicians took a more holistic approach to the implications of a loss.

Discussion

We sought to determine how physicians and midwives in Ghana make sense of and cope with high levels of perinatal mortality. Responses were most notable for providers’ commitment to keep going with their work and offer the best care possible, which was observed across participants and specialties. Moreover, select providers sought to be agents of change in a struggling system. This research offers a unique contribution to the literature on healthcare worker coping and perinatal mortality as it is the first study to our knowledge to address this issue in a low-resource setting [1–4]. The inclusion of physicians and midwives is a noteworthy addition to this research.

Most existing research from low-resource settings on healthcare providers’ responses to death has focused on emotional distress and burnout [6, 7]. Our work showed elements of depersonalization, as is documented throughout the world [16], but was dominated by providers’ commitment to pushing on and providing the best care possible. Similar themes are documented among Ugandan nurses, who demonstrated a firm professional identity and deep commitment to helping, despite limited resources [17]. Tanzanian maternal and newborn healthcare providers derived substantial job satisfaction from providing competent, helpful care [18]. Such stories of resilience may be overlooked, as in the midst of the challenges facing low-resource nations we tend not to recognize their strengths.

The pattern of control and engagement was consistent with Latack’s description of control/proactive orientations [11]. Of note, many of the externally-oriented, low control statements cite clear contributors to perinatal death [19], particularly issues of resources in the environment as a whole. Given Bandura’s theory that stronger self-efficacy will lead to increased effort and success in coping, recognizing these factors may help providers contextualize their role in a setting of frequent deaths [10]. Similar frustrations with inadequate resources have been documented among healthcare workers in Ghana and elsewhere [18, 20]. However, our participants found more proactive coping approaches to be valuable. They reported that not having opportunities to grieve and “being cold” were problematic; that talking about the death was useful; and that evaluating their management of a situation was helpful. This is consistent with coping research showing that control-oriented strategies are more emotionally effective [12]. Furthermore, we postulate that increasing engagement with the death process can bring meaning to one’s work. Thus, we propose that the implications of this continuum of control/self-efficacy and engagement are that behaviors and attitudes higher on the spectrum are more supportive to providers continuing with their work.

Even with the impressive level of resilience our participants demonstrated, there is a need to further understand and support healthcare providers’ coping with perinatal death. Providers’ responses and needs will vary by setting so research on coping should be expanded to additional sites and countries. This could aid in identifying and ultimately disseminating the most helpful and positive strategies. As one obstetrician-gynecologist pointed out when discussing global healthcare worker migration, “those of us who are left must have the correct attitude.” This is a reminder that a workforce’s capacity is determined by the efforts of its members as well as its size. Ongoing work appropriately seeks to reduce perinatal mortality by building the global healthcare workforce [21]. In doing so, we must recognize the intense stressors of working in low-resource settings with high levels of death and dying. Training should aim to strengthen providers’ coping abilities for the more emotionally challenging aspects of their work, focusing on strategies which help them develop higher levels of self-efficacy.

Strengths of this research included its incorporating a range of clinicians. Relating identified themes to published frameworks on coping extends the value of this study. Limitations include the study site of a single tertiary care center in one country, which limits generalizability. Within Ghana, transferability is limited by the fact that this is a tertiary care center and thus relatively better-resourced than many hospitals; however, it should be generalizable to other tertiary referral centers and large hospitals, which are likely to see similarly high mortality rates. Also, data was collected over two discrete time periods, with interviews in the second time block including more obstetricians–gynecologists and generally being longer. Although these are potential confounders, we did not observe marked discrepancies across the specialties. We also saw no evidence in the responses to suggest there were variations based on the length of the interview (which was typically set by the length of the respondent’s answers and his or her willingness to elaborate). It is possible that there were variations among interviewers, but no clear patterns emerged; however, the use of multiple interviewers may still have been a limitation. Though we did not hypothesize that there would be differences based on participants’ specialty, gender or time in practice, the lack of noteworthy variations across these domains suggests either that response patterns are truly similar among providers of different specialties, gender, and duration of practice, or that this qualitative study was not able to detect differences based on our queries or sample size. The use of medical student interviewers who had minimal contact with subjects clinically is a strength, as we believe providers were more likely to be open with those junior to them and see them as less threatening. It is possible that they may have withheld information from people seen as outsiders, however given the candidness of many the comments received this is unlikely to have been the case. A final limitation is that due to logistical matters of the international field work, analysis of the transcripts occurred after data collection had been completed, thus true thematic saturation was not achieved.

In summary, our work shows that physicians and midwives in Ghana make sense of and cope with high rates of perinatal mortality in a variety of ways, most notable for a commitment to pushing on and providing the best care possible. They demonstrated significant resilience amidst challenging conditions, for which they deserve recognition and further work to bolster their ability to cope with greater self-efficacy and engagement.

References

Nuzum, D., Meaney, S., & O’Donoghue, K. (2014). The impact of stillbirth on consultant obstetrician gynaecologists: A qualitative study. BJOG, 121, 1020–1028.

Chen, F. H., & Hu, W. Y. (2013). The impact of perinatal death on nurses and their coping strategies [English abstract]. Hu li za zhi Journal of Nursing, 60, 87–91.

Wallbank, S., & Robertson, N. (2008). Midwife and nurse responses to miscarriage, stillbirth and neonatal death: A critical review of qualitative research. Evidence Based Midwifery, 6, 100–106.

Jonas-Simpson, C., Pilkington, F. B., MacDonald, C., & McMahon, E. (2013). Nurses’ experiences of grieving when there is a perinatal death. SAGE Open, 3, 1–11. http://sgo.sagepub.com/content/spsgo/3/2/2158244013486116.full.pdf.

Gold, K. J., Kuznia, A. L., & Hayward, R. A. (2008). How physicians cope with stillbirth or neonatal death: A national survey of obstetricians. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 112, 29–34.

Masia, R. T., Basson, W. J., & Ogunbanjo, G. A. (2010). Emotional reactions of medical doctors and students following the loss of their patients at the Dr George Mukhari Hospital emergency unit, South Africa. South African Family Practice, 52, 356–363.

Sardiwalla, N., VandenBerg, H., & Esterhuyse, K. G. (2007). The role of stressors and coping strategies in the burnout experienced by hospice workers. Cancer Nursing, 30, 488–497.

Rajaratnam, J. K., Marcus, J. R., Flaxman, A. D., et al. (2010). Neonatal, postneonatal, childhood, and under-5 mortality for 187 countries, 1970-2010: A systematic analysis of progress towards Millennium Development Goal 4. The Lancet, 375, 1988–2008.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191–215.

Latack, J. C., & Havlovic, S. J. (1992). Coping with job stress: A conceptual evaluation framework for coping measures. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13, 479–508.

Leiter, M. P. (1992). Coping patterns as predictors of burnout: The function of control and escapist coping patterns. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 12, 123–144.

Bennett, L., Ross, M. W., & Sunderland, R. (1996). The relationship between recognition, rewards and burnout in AIDS caring. AIDS Care, 8, 145–153.

Dieleman, M., Biemba, G., Mphuka, S., et al. (2007). ‘We are also dying like any other people, we are also people’: Perceptions of the impact of HIV/AIDS on health workers in two districts in Zambia. Health Policy Plan, 22, 139–148.

Gold, K. J., Abdul-Mumin, A. R., Boggs, M. E., Opare-Addo, H. S., & Lieberman, R. W. (2014). Assessment of “fresh” versus “macerated” as accurate markers of time since intrauterine fetal demise in low-income countries. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, 125, 223–227.

Lee, R. T., Seo, B., Hladkyj, S., Lovell, B. L., & Schwartzmann, L. (2013). Correlates of physician burnout across regions and specialties: A meta-analysis. Human Resources for Health, 11, 48.

Harrowing, J. N., & Mill, J. (2010). Moral distress among Ugandan nurses providing HIV care: A critical ethnography. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 47, 723–731.

Prytherch, H., Kakoko, D. C., Leshabari, M. T., Sauerborn, R., & Marx, M. (2012). Maternal and newborn healthcare providers in rural Tanzania: In-depth interviews exploring influences on motivation, performance and job satisfaction. Rural and Remote Health, 12, 2072.

Bhutta, Z. A., Darmstadt, G. L., Haws, R. A., Yakoob, M. Y., & Lawn, J. E. (2009). Delivering interventions to reduce the global burden of stillbirths: Improving service supply and community demand. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 9(Suppl 1), S7.

Opoku, S. T., & Apenteng, B. A. (2014). Career satisfaction and burnout among Ghanaian physicians. International Health, 6, 54–61.

Chen, L., Evans, T., Anand, S., et al. (2004). Human resources for health: Overcoming the crisis. The Lancet, 364, 1984–1990.

Acknowledgments

Travel and study support were provided by GlobalREACH and the Student Biomedical Research Program of the University of Michigan. Dr. Gold received salary support from a K-23 from the National Institute of Mental Health. No funder had any role in project development, data collection, or review of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Petrites, A.D., Mullan, P., Spangenberg, K. et al. You have no Choice but to go on: How Physicians and Midwives in Ghana Cope with High Rates of Perinatal Death. Matern Child Health J 20, 1448–1455 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-016-1943-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-016-1943-y