Abstract

The objectives of this study were to determine if racial and ethnic differences in personal capital during pregnancy exist and to estimate the extent to which any identified racial and ethnic differences in personal capital are related to differences in maternal sociodemographic and acculturation characteristics. Data are from the 2007 Los Angeles Mommy and Baby study (n = 3,716). Personal capital comprised internal resources (self-esteem and mastery) and social resources (partner, social network, and neighborhood support) during pregnancy. The relationships between race/ethnicity and personal capital were assessed using multivariable generalized linear models, examining the impact of sociodemographic and acculturation factors on these relationships. Significant racial and ethnic disparities in personal capital during pregnancy exist. However, socioeconomic status (i.e., income and education) and marital status completely explained Black-White disparities and Hispanic-White disparities in personal capital, whereas acculturation factors, especially nativity and language spoken at home, partially mediated the disparities in personal capital between Asian/Pacific Islander women and White women. Findings suggest that the risks associated with low socioeconomic status, single motherhood, and low acculturation, rather than race or ethnicity, contribute to low personal capital for many pregnant women. As personal capital during pregnancy may influence subsequent maternal and child health outcomes, the development of interventions should consider addressing sociodemographic and acculturation factors in order to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in personal capital and ultimately in poor maternal and child health outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Maternal and child health (MCH) outcomes in the United States vary significantly by maternal race and ethnicity [1–6]. Prior studies point to differentials in socioeconomic status (SES), exposures to stressful life events and chronic stressors, access to health services and other health-promoting resources, and risky health behaviors as possible explanations for these differences [2, 3, 7–11]. However, exploring the protective resources that women may draw upon during pregnancy, or personal capital, that decrease their vulnerability to adverse MCH outcomes is equally important. Furthermore, determining if and how personal capital differs by race and ethnicity is crucial for designing interventions to reduce disparities in MCH outcomes.

However, little is known about personal capital during pregnancy. We define personal capital during pregnancy as internal and social resources that help women cope with or decrease their exposure to the psychological (e.g. acute and chronic stress) and behavioral (e.g. risky health behaviors) factors [12] associated with adverse MCH outcomes. Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model [13, 14] provides a framework to conceptualize how personal capital may operate on multiple levels to impact adverse MCH outcomes. At the individual level, internal resources (i.e., self-esteem and mastery) have been associated with higher infant birthweight [15] and decreased risk of intrauterine growth retardation [16]. At the interpersonal level, social resources, such as partner support and social network support, have been linked to increased fetal growth [17], better labor progress [18], higher birthweight [18], and higher infant APGAR scores [18]. At the community level, neighborhood support may play an indirect role in lowering women’s risk of adverse obstetric outcomes [19].

Though studies have not examined personal capital as a composite construct, many have explored racial and ethnic disparities in the individual components of personal capital. Regarding internal resources, studies indicate that compared to other racial and ethnic groups, Blacks have reported higher levels of self-esteem, whereas Asians have reported the lowest levels [20, 21]. One hypothesis explaining the Asian self-esteem disadvantage is that while Whites have relatively favorable attitudes towards Asians, they still harbor negative stereotypes about Asians, who, in turn, internalize this stigma and have decreased self-esteem [21]. Regarding social resources, Hispanic women have reported relatively high partner and social network support, likely due to the cultural emphasis on “familismo,” or solid family/kinship ties [22–25]. In contrast, studies have shown that Black mothers are more likely to be adolescent parents, be unmarried, and receive lower partner support than other racial/ethnic groups [26–28]. Finally, the literature suggests that all racial and ethnic groups prefer to live in racially segregated neighborhoods, attributable to the increased likelihood of developing culturally congruent social networks [29–32]. Also, residing in these neighborhoods may be favorable to minorities because it confers emotional benefits, including elevated self-esteem and psychological well-being, due to the decreased likelihood of discrimination and increased social support [31].

As previous studies have provided evidence of the protective independent effects of personal capital components on MCH outcomes [15–19], we expand this work by incorporating these critical resources into a unified construct to comprehensively capture the available resources that women may garner during pregnancy. To our knowledge, we are the first to explore a conceptually-based, multi-dimensional measure of personal capital. We used data from the 2007 Los Angeles Mommy and Baby (LAMB) study to determine racial and ethnic differences in personal capital (i.e., the composite measure and the individual components) among pregnant women living in Los Angeles and estimate the extent to which any identified disparities in personal capital are related to differences in maternal sociodemographic and acculturation characteristics. By identifying the characteristics associated with low personal capital, this research will have important implications for developing targeted public health interventions.

Methods

Sample

Data are from 3,716 women who participated in the 2007 LAMB study, a cross-sectional, population-based study that examined preconception, prenatal, and postpartum correlates of adverse MCH outcomes. Eligible mothers were Los Angeles County residents who had given birth to a live-born infant in Los Angeles County in 2007.

The 2007 LAMB Study was a collaboration between the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) and the Los Angeles County Department of Maternal, Child and Adolescent Health. They employed a stratified random sample, selected by sampling neighborhoods based on census tracts and then sampling births within the neighborhoods, resulting in a sample of 4,518 women. The response rate for the Los Angeles County sample was 56 %, after adjusting for faulty addresses, language issues, maternal deaths, and loss to follow-up due to inability to locate the respondent.

Respondents with missing values for personal capital variables (n = 762) and respondents who did not belong to one of the four main race/ethnic groups (n = 49) were removed by listwise deletion, resulting in a final sample of 3,716 women for the present analyses. We compared the sociodemographic and acculturation characteristics among women with missing (n = 802) and complete (n = 3,716) data; women with missing data were significantly more likely to be young, Hispanic, unmarried, primaparous, foreign-born, newly immigrated, non-English speaking, low-income, and less educated.

Procedures

In 2007, over 10,000 surveys were mailed to eligible women within 6 months after delivery. The recruitment process entailed a(n): (1) mailed preletter 4 months after childbirth; (2) initial mailed questionnaire 1 week later; (3) mailed reminder 1 week later; (4) second mailed questionnaire 2 weeks later (if needed); and (4) telephone follow-up 2 weeks later (if needed) (Appendix 1). Finally, the data from the completed surveys were linked to corresponding California birth certificates prior to analyses.

This study was approved by both the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health and UCLA Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) in 2007. As only secondary data analysis was involved in this work, a Restricted Data Agreement was signed to access the LAMB study data, and an exemption, with waiver of informed consent, was granted by the Los Angeles County IRB.

Measures

Personal Capital

Personal capital comprised internal resources (i.e., self-esteem and mastery), partner support, social network support, and neighborhood support. Items within each personal capital component were summed to create raw scores for the component, with higher scores reflecting greater levels of that component. Table 1 describes the operationalization and reliability (i.e., standardized Cronbach’s alphas) of each personal capital component in our study, and Appendix 2 delineates the items constituting each component. Self-esteem was defined as a “positive or negative orientation toward oneself or an overall evaluation of one’s worth or value” ([33], p. 70). Mastery embodied the belief that one has control over her life [15]. Partner support encompassed instrumental and emotional support from the baby’s father [34]. Social network support included support from a woman’s kin and close friends [35]. Neighborhood support concerned neighborhood social cohesion and reciprocal exchange [36].

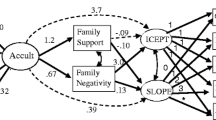

The personal capital score was created using a weighting scheme based on a conceptual rationale (Fig. 1). Proximal resources were weighed more heavily than distal resources as they were posited to have a larger and more direct impact on the individual. As such, internal resources, partner support, social network support, and neighborhood support comprised 32.5, 27.5, 22.5, and 17.5 %, respectively, of the overall score. The weighted personal capital score was standardized to range from 1 to 100, with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10.

Construction and Distribution of Personal Capital, 2007 Los Angeles Mommy and Baby (LAMB) Study. The personal capital score was created using a weighting scheme based on Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model and comprised internal resources, partner support, social network support, and neighborhood support. Proximal resources were weighed more heavily than distal resources as they were posited to have a larger and more direct impact on the individual. As such, internal resources, partner support, social network support, and neighborhood support comprised 32.5, 27.5, 22.5, and 17.5 %, respectively, of the overall score. Therefore, the figure graphically depicts how each component was weighted and then summed to create the composite measure of personal capital. The weighted personal capital score was standardized to range from 1 to 100, with a mean of 50 and a SD of 10; the histogram illustrates the distribution of the standardized personal capital scores within our sample of women (n = 3,716) from the 2007 LAMB study

Race/Ethnicity

Race/ethnicity data, listed as the “race” and “ethnicity” (Hispanic or non-Hispanic) of the mother, were obtained from California birth certificates. The categories used included: White (including European and Middle Eastern), Black, Hispanic, and Asian/Pacific Islander (API) (including Southeast Asian) [37]. When two race/ethnicities were provided, California birth certificates used the first one that was listed.

Sociodemographic Factors

The analyses accounted for the following sociodemographic variables: annual household income (≤$19,000, $20,000–$39,000, $40,000–$59,000, $60,000–$99,000, ≥$100,000), education (<versus ≥12 years of schooling), and marital status (married, single/never married, separated/divorced/widowed, cohabiting). Married and cohabiting women were examined separately because cohabitation may not incur the same support benefits as marriage [28]. While the data for education was found in the birth certificates, income and marital status were self-reported in the survey.

Acculturation Factors

Acculturation factors, including nativity (US-born vs. foreign-born), language primarily spoken at home (English vs. non-English), and percentage of life resided in the US (continuous), were either found in or derived from the survey. Percentage of life in the US was calculated by dividing the length of residence by maternal age and then multiplying the quotient by 10 for interpretability of the coefficient.

Control Variables

The analyses also controlled for maternal age (continuous), the number of prior children ≤5 years old (continuous) and parity (primaparous vs. multiparous). Data for age were from birth certificates, whereas data for parity and the number of children ≤5 years old were contained in the survey. We also added household size and the number of postpartum days in which the survey was completed to the models.

Analytic Approach

Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and were weighted to account for sampling design and survey non-response. First, one-way ANOVA tests compared the mean scores for overall personal capital and components for each sociodemographic and acculturation characteristic. Second, to assess the roles of sociodemographic and acculturation factors in the relationship between race/ethnicity and personal capital (overall score and components), multivariable generalized linear models were used, consisting of the following variables: (1) Race/ethnicity (Model 1); (2) Race/ethnicity, age, parity and number of children ≤5 years old (Model 2); (3) All Model 2 variables and all sociodemographic variables (Model 3); and (4) All Model 3 variables and all acculturation variables (Model 4). Third, Sobel tests [38] were used to ascertain if certain factors mediated the association between race/ethnicity and personal capital. Sensitivity analyses which compared models containing household size and the number of postpartum days in which the survey was completed with models not containing them yielded very similar findings; therefore, in order to employ the most parsimonious models, we did not incorporate these variables into the present analyses.

Results

Description of Sample and Personal Capital Scores by Sociodemographic and Acculturation Characteristics

Most respondents were 19–34 years old, multiparous, English-speaking, or had incomes ≤$39,000 or ≥12 years of schooling (Table 2). Over half of the women were married, US-born, had no prior children ≤5 years old, or had resided in the US for longer than 75 % of their lives. The majority of respondents were Hispanic. Half of the Hispanic women were US-born, and 44 % were from Mexico. In contrast, only 20 % of API women were US-born, and foreign-born API women originated mainly from the Philippines, China, Vietnam, Korea and Taiwan.

Overall, our sample’s weighted mean score for personal capital was 48.90. Respondents who had an annual household income ≤$19,000, <12 years of schooling, at least two prior children ≤5 years old, or were ≤18 years old, primaparous, non-White, unmarried, foreign-born, non-English speaking, or newly immigrated had, on average, lower personal capital scores.

Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Personal Capital

Black, Hispanic and API women reported significantly lower overall personal capital than White women, such that the magnitude of the disparities were equivalent to one-half of a standard deviation for Black women, 60 % of a standard deviation for Hispanic women, and one-third of a standard deviation for API women (Table 2). Black and Hispanic women reported lower partner support than White and API women. Hispanic women, specifically respondents from Honduras and El Salvador, reported the lowest social network support. All women reported low neighborhood support, with Black and API women, specifically Japanese women, reporting the lowest support.

To further evaluate racial and ethnic differences in personal capital, multivariable generalized linear models were estimated. These analyses (Table 3) showed that on average, Black, Hispanic, and API women had significantly lower personal capital (4.2, 4.9, and 3.5 points lower, respectively) than White women, controlling for confounders (Model 2). When we added sociodemographic variables to this model to determine if they mediated the disparities in personal capital (Model 3), the effect of being Black or Hispanic was eliminated and no longer statistically significant (β = 0.87, p = 0.27 and β = −0.73, p = 0.14, respectively), whereas API women still reported significantly lower overall personal capital (β = −2.91; p < 0.001), internal resources (β = −2.06; p < 0.001), and neighborhood support (β = −2.77; p < 0.001) than White women. Sobel test findings confirmed that income (≤$19,000: Z-value = −7.4, p < 0.001) and marital status (separated/divorced/widowed: Z = −3.3, p < 0.001; single/never married: Z = −8.2, p < 0.001) explained the disparities for Black women, whereas income (≤$19,000: Z = −12.0, p < 0.001) and education (<12 years of schooling: Z = −9.1, p < 0.001) explained the disparities for Hispanic women. To ascertain the potential mechanisms leading to the API-White disparities in personal capital, the role of acculturation was explored. Accounting for all acculturation variables reduced disparities in overall personal capital for API women (Table 3). Sobel tests confirmed that nativity, language spoken at home, and time in the US (Z = −4.1, Z = −4.9, and Z = −6.0, respectively; p < 0.001 for all) each partially mediated disparities in overall personal capital for API women.

To further examine racial and ethnic differences in each of the components of personal capital, multivariable generalized linear models were estimated. These analyses (Table 4) showed that adjusting for sociodemographic variables completely mediated disparities in partner support and neighborhood support for Black women and in all personal capital components for Hispanic women. Sobel tests indicated that income (≤$19,000) played an especially salient role in reducing the disparities in neighborhood support (Z = −4.0, p < 0.001) for Black women and in internal resources (Z = −8.8, p < 0.001) and neighborhood support (Z = −5.2, p < 0.001) for Hispanic women. Additionally, marital status specifically attenuated the disparity in partner support for Black women (separated/divorced/widowed: Z = −3.8, p < 0.001; single/never married: Z = −10.8, p < 0.001).

Accounting for all acculturation variables also reduced disparities in social network support and neighborhood support for API women (Table 4). Sobel tests indicated that nativity, language spoken at home, and percentage of life in the US each partially mediated disparities in internal resources (Z = −5.6, Z = −5.9, and Z = −7.3, respectively; p < 0.001 for all) for API women. Additionally, for API women, being non-English speaking attenuated disparities in social network support (Z = −2.9, p = 0.004) and neighborhood support (Z = −2.3, p = 0.024), whereas time in the US attenuated disparities in social network support (Z = −3.9, p < 0.001).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to conceptualize personal capital during pregnancy as a composite construct comprising protective resources that operate on multiple levels, thereby filling a critical gap in the literature, as previous work has only considered the individual components of personal capital [15–32]. Our findings indicate that racial and ethnic differences in personal capital exist. Moreover, disparities for Black and Hispanic women were completely explained by sociodemographic factors, whereas the disparities for API women were attenuated by acculturation factors. Therefore, this study suggests that, the risks associated with low SES, single motherhood, and low acculturation, rather than race or ethnicity, contribute to low personal capital for many minority pregnant women.

In our study, Black women reported the lowest partner support, thus corroborating findings in the extant literature [26, 39–43]. Marital status, and to a lesser degree, income, attenuated the significant Black-White disparities in partner support, therefore providing evidence that single motherhood and low income, rather than race itself, contribute to lower partner support among Black mothers. Further, single motherhood may likely co-occur with poverty if single mothers receive low paternal financial assistance, possibly related to the increased likelihood of having children with multiple partners [39]. Multi-partnered fertility has been shown to reduce fathers’ emotional and economic investment in their children if they transition into new relationships, and couples are less likely to marry or cohabit after the baby’s birth if the father has existing children with another partner [39–43].

Hispanic women reported the lowest social network support, thereby challenging previous findings [25]. Hispanic-White disparities in social network support were completely mediated by SES (i.e., income and education). This finding contradicts the Latino Paradox, by which Hispanics, who have similar SES characteristics as Blacks, have better outcomes than Blacks and even Whites in some cases [25, 44, 45]. Though some empirical evidence supports the positive association between SES and social support among Hispanic women [46], low SES is likely related to low acculturation, which has been linked to low social network support [47, 48]. New immigrants may be in a transitional phase, such that they have left behind valuable social networks in their native countries and are currently unable to garner viable social ties in the US due to economic, lingual, and racial barriers [49, 50].

Most notably, we found that even after accounting for sociodemographic factors, API women reported significantly lower overall personal capital, internal resources and neighborhood support than White women and that these disparities were partially mediated by acculturation factors. The findings regarding internal resources have been substantiated in the literature, and self-esteem among Asians has also been positively associated with exposure to American culture [21]. As API women clustered in four Los Angeles regions, the findings regarding their low neighborhood support contradicts the extant residential segregation literature, which suggests that immigrants form stronger social network ties within ethnic enclaves [51–53]. However, immigrants who become more socioeconomically secure have been shown to move to high-SES neighborhoods to live alongside Whites [54]; thus, they may not obtain the same support benefits as they would in predominantly Asian neighborhoods. Additionally, our findings are consistent with the literature that has highlighted the mediating effects of acculturation on neighborhood support among API’s [55].

Several potential limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, as the survey was administered postpartum, the responses regarding prenatal experiences may be vulnerable to recall bias. Second, the mother’s current relationship with the baby’s father was unknown and may have biased responses about partner support during pregnancy. Third, the race/ethnicity categories on the birth certificates were broad, and women may have been inaccurately grouped into a particular category [37]. Fourth, women with missing data for personal capital variables were removed from the analyses; however, given the sociodemographic and acculturation characteristics of women with missing data, our findings were likely conservative estimates of the examined associations. Additionally, though the reliability of the composite personal capital score was fairly low, each of the components had relatively high reliability, thereby supporting our aim of developing a composite personal capital measure comprising conceptually distinct, non-redundant components; however, future researchers should consider this potential limitation when attempting to create a latent construct for personal capital. Finally, the extent to which our measures were culturally appropriate is unknown and should be further examined in future research.

The LAMB study also had some potential limitations. The study’s cross-sectional nature precluded the assumption of causality between predictors and outcomes. Also, it had a relatively low response rate, though we argue that non-respondents were at higher risk for having low personal capital and that our findings were thus conservative estimates of the examined associations. Finally, though the study sample was diverse and representative of the Los Angeles population, the findings may not be generalizable to other populations.

Our findings have important implications for public health interventions as multiple opportunities exist at the individual, interpersonal, and community levels to increase personal capital among women who are planning pregnancy or become pregnant. We posit that programs that offer comprehensive resources (e.g. individual, group, and couples counseling, group prenatal care, free legal aid for single mothers to obtain child support, free/subsidized neighborhood-based childcare) incorporating multiple facets of personal capital are likely to be most beneficial for improving MCH outcomes. However, as the components of personal capital are likely interrelated, addressing at least one resource may help women increase other critical resources; for example, participation in prenatal group therapy sessions may foster social network support, which may elevate self-esteem and empower women to communicate their needs more assertively to their partners and in turn, receive greater partner support.

Furthermore, this study contributes to the literature by providing critical insights into the complexities of racial and ethnic disparities in personal capital, a novel construct that is grounded in theory and has promising implications for the prevention of adverse MCH outcomes. This study fills gaps in the literature regarding understudied populations (e.g. API women) and inadequately explored constructs (e.g. mastery). Furthermore, the study was conducted in Los Angeles, a population with diverse sociodemographic and acculturation characteristics. The sizeable number of API mothers is a unique strength of the LAMB study, as most perinatal studies do not include a sufficient number of API women to allow for meaningful analysis. While it supports many previous findings, this study also offers new evidence that challenges traditional stereotypes, such as Hispanics possessing higher social network support [25], acculturation being associated with negative outcomes [56], and minorities experiencing higher neighborhood support than Whites [51–53]. Further research is needed to determine if these findings persist in other populations. Additionally, in order to identify effective points of intervention during the lifecourse, longitudinal research should explore how personal capital may evolve differently over time for women of different racial and ethnic backgrounds. Ultimately, examining racial and ethnic disparities in personal capital during pregnancy is an instrumental piece in informing clinical, programmatic, and policy interventions to reduce disparities in adverse MCH outcomes.

References

MacDorman, M. F. (2011). Race and ethnic disparities in fetal mortality, preterm birth, and infant mortality in the United States: An overview. Seminal Perinatology, 35(4), 200–208.

Finch, B. K., Frank, R., & Hummer, R. A. (2000). Racial/ethnic disparities in infant mortality: The role of behavioral factors. Biodemography and Social Biology, 47(3–4), 244.

Lu, M. C., & Halfon, N. (2003). Racial and ethnic disparities in birth outcomes: A life-course perspective. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 7(1), 13–30.

Culhane, J. F., & Goldenberg, R. L. (2011). Racial disparities in preterm birth. Seminal Perinatology, 35(4), 234–239.

Hauck, F. R., Tanabe, K. O., & Moon, R. Y. (2011). Racial and ethnic disparities in infant mortality. Seminal Perinatology, 35(4), 209–220.

Rosenthal, L., & Lobel, M. (2011). Explaining racial disparities in adverse birth outcomes: Unique sources of stress for Black American women. Social Science and Medicine, 72(6), 977–983.

Corbie-Smith, G., Henderson, G., Blumenthal, C., Dorrance, J., & Estroff, S. (2008). Conceptualizing race in research. Journal of National Medical Association, 100(10), 1235–1243.

Krieger, N. (2000). Counting accountability: Implications of the new approaches to classifying race/ethnicity in the 2000 census. American Journal of Public Health, 90(11), 1687–1689.

Jones, C. P. (2001). Race, racism, and the practice of epidemiology. American Journal of Epidemiology, 154(4), 299–304.

Williams, D. R. (1997). Race and health: Basic questions, emerging directions. Annals of Epidemiology, 7(5), 322–333.

Lillie-Blanton, M., & LaVeist, T. A. (1996). Race/ethnicity, the social environment, and health. Social Science and Medicine, 43(1), 83–91.

Dunkel Schetter, C. (2011). Psychological science on pregnancy: stress processes, biopsychosocial models, and emerging research issues. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 531–558.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32, 513–531.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Rini, C., Dunkel-Schetter, C., Sandman, C., & Wadhwa, P. (1999). Psychological adaptation and birth outcomes: the role of internal resources, stress, and sociocultural context in pregnancy. Health Psychology, 18(4), 333–345.

Goldenberg, R., Cliver, S., Cutter, G., Hoffman, H., Copper, R., Gotlieb, S., et al. (1991). Maternal psychological characteristics and intrauterine growth retardation. Journal of Prenatal & Perinatal Psychology & Health, 6(2), 129–134.

Feldman, P., Dunkel-Schetter, C., Sandman, C., & Wadhwa, P. (2000). Maternal social support predicts birth weight and fetal growth in human pregnancy. Psychosomatic Medicine, 62, 715–725.

Collins, N. L., Dunkel-Schetter, C., Lobel, M., & Scrimshaw, S. C. (1993). Social support in pregnancy: psychosocial correlates of birth outcomes and postpartum depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(6), 1243–1258.

Bell, J. F., Zimmerman, F. J., Almgren, G. R., Mayer, J. D., & Huebner, C. E. (2006). Birth outcomes among urban African-American women: A multilevel analysis of the role of racial residential segregation. Social Science and Medicine, 63, 3030–3045.

Zeigler-Hill, V. (2007). Contingent self-esteem and race: Implications for the Black self-esteem advantage. Journal of Black Psychology, 33(1), 51–74.

Twenge, J. M., & Crocker, J. (2002). Race and self-esteem: meta-analyses comparing whites, blacks, Hispanics, Asians, and American Indians and comment on Gray-Little and Hafdahl (2000). Psychological Bulletin, 128(3), 371–408.

Norbeck, J. S., & Anderson, N. J. (1989). Psychosocial predictors of pregnancy outcomes in low-income Black, Hispanic and White women. Nursing Research, 38, 204–209.

Diaz, M. A., Le, H. N., Cooper, B. A., & Munoz, R. F. (2007). Interpersonal factors and perinatal depressive symptomatology in a low-income Latina sample. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 13(4), 328–336.

West, C., Kantor, G., & Janiski, J. (1998). Sociodemographic predictors and cultural barriers to help-seeking behavior by Latina and Anglo American battered women. Violence Victims, 13(4), 361–375.

Campos, B., Dunkel Schetter, C., & Abdou, C. (2008). Familialism, Social support, and stress: positive implications for pregnant Latinas. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 14(2), 155–162.

Gee, C., McNerney, C., Reiter, M., & Leaman, S. (2007). Adolescent and young adult mothers’ relationship quality during the transition to parenthood: associations with father involvement in Fragile Families. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36, 213–224.

Hanson, S., Morrison, D., & Ginsburg, A. (1989). The antecedents of teenage fatherhood. Demography, 26, 579–596.

Lichter, D. T., LeClere, F. B., & McLaughlin, D. K. (1991). Local marriage markets and the marital behavior of black and white women. American Journal of Sociology, 96(4), 843–867.

Clark, W. (1992). Residential preferences and residential choices in a multiethnic context. Demography, 29(3), 451–466.

Krysan, M., & Farley, R. (2002). The residential preferences of Blacks: Do they explain persistent segregation? Social Forces, 80(3), 937–980.

Vogt Yuan, A. S. (2008). Racial composition of neighborhood and emotional well-being. Sociological Spectrum, 28(1), 105–129.

Zubrinky, C., & Bobo, L. (1996). Prismatic metropolis: Race and residential segregation in the city of the angels. Social Science Research, 25, 335–374.

Jesse, E., Graham, M., & Swanson, M. (2006). Psychosocial and spiritual factors associated with smoking and substance use during pregnancy in African-American and White low-income women. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecological, & Neonatal Nursing, 35(1), 68–77.

Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study. (2003). Mother’s baseline questionnaire. http://www.fragilefamilies.princeton.edu/documentation.asp.

Adams, M., Shulman, H., Bruce, C., Hogue, C., & Brogan, D. (1991). The pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system: design, questionnaire, data collection and response rates. PRAMS Working Group. Paediatric and Perinatology Epidemiology, 5, 333–346.

Buka, S., Brennan, R., Rich-Edwards, J., Raudenbush, S., & Earls, F. (2003). Neighborhood support and birth weight of urban infants. American Journal of Epidemiology, 157(1), 1–8.

Baumeister, L., Marchi, K., Pearl, M., Williams, R., & Braveman, P. (2000). The validity of information on ‘race’ and ‘Hispanic ethnicity’ in California birth certificate data. Health Services Research, 35, 869–883.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Guzzo, K. B., & Furstenberg, F. F. J. (2007). Multipartnered fertility among American men. Demography, 44(3), 583–601.

Manning, W., & Smock, P. (2000). “Swapping” families: Serial parenting and economic support for children. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 111–122.

Harknett, K., & Knab, J. (2007). More kin, less support: Multipartnered fertility and perceived support among mothers. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69(1), 237–253.

Carlson, M. J., & Furstenberg, F. F. J. (2006). The prevalence and correlates of multipartnered fertility among urban US parents. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68(3), 718–732.

Carlson, M. J., McLanahan, S., & England, P. (2004). Union formation in fragile families. Demography, 41, 237–262.

Goldman, N., Kombro, R., Cassio, T., & Pebley, A. R. (2006). Socioeconomic gradients in health for White and Mexican-origin populations. American Journal of Public Health, 96(12), 2186–2193.

Lin, C. C., Rogot, E., Johnson, N. J., Sorlie, P. D., & Arias, E. (2003). A further study of life expectancy by socioeconomic factors in the National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Ethnicity and Disease, 13(2), 240–247.

Almeida, J., Molnar, B. E., Kawachi, I., & Subramanian, S. V. (2009). Ethnicity and nativity status as determinants of perceived social support: Testing the concept of familism. Social Science and Medicine, 68(10), 1852–1858.

Vega, W., Kolody, B. (1985). The meaning of social support and the mediation of stress across cultures. In Vega, W. A., & Miranda, M. R. (eds), Stress and Hispanic mental health. (Vol. DHHS Publication No.85-1410). Washington, DC: National Institute of Mental Health.

Harley, K., & Eskenazi, B. (2006). Time in the United States, social support and health behaviors during pregnancy among women of Mexican descent. Social Science and Medicine, 62, 3048–3061.

Keefe, S., & Padilla, A. (1987). Chicano ethnicity. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Sundquist, J., & Winkleby, M. A. (1999). Cardiovascular risk factors in Mexican American adults: A transcultural analysis of NHANES III, 1988–1994. American Journal of Public Health, 89(5), 723–730.

Cagney, K. A., Browning, C. R., & Wallace, D. M. (2007). The Latino paradox in neighborhood context: the case of asthma and other respiratory conditions. American Journal of Public Health, 97(5), 919–925.

Peak, C., & Weeks, J. R. (2002). Does community context influence reproductive outcomes of Mexican origin women in San Diego, California? Journal of Immigrant Health, 4(3), 125–136.

Gibson, M. A. (1988). Punjabi orchard farmers: an immigrant enclave in rural California. International Migration Review, 22(1), 28–50.

Iceland, J., & Nelson, K. A. (2010). The residential segregation of mixed-nativity married couples. Demography, 47(4), 869–893.

Zhang, W., & Ta, V. M. (2009). Social connections, immigration-related factors, and self-rated physical and mental health among Asian Americans. Social Science and Medicine, 68(12), 2104–2112.

Ceballos, M., & Palloni, A. (2010). Maternal and infant health of Mexican immigrants in the USA: The effects of acculturation, duration, and selective return migration. Ethnic Health, 15(4), 377–396.

Acknowledgments

This project was made possible by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) Grant # R40MC06635, the Los Angeles County Productivity and Investment fund, and the Los Angeles County Department of Maternal, Child and Adolescent Health (MCAH) Programs general grants and was completed in collaboration with 2007 LAMB Principal Investigator M.C. Lu. LW was supported by a Grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) (T32 HS000083; Principal Investigator M. Smith). FW was supported by a Grant from the Health Disparities Research Training Program (T32 HD049302; Principal Investigator G. Sarto). We would like to thank the Los Angeles Mommy and Baby (LAMB) study team (Chandra Higgins, Diana Liu, Marian Eldahaby, Carmen Gutierrez, Yvornia Horton, and Martha Martinez) for their dedicated work in the design and implementation of the 2007 LAMB project. We would also like to thank the Lifecourse Epidemiology and Family Health (LEAF) team for their incredible support with the editing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wakeel, F., Witt, W.P., Wisk, L.E. et al. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Personal Capital During Pregnancy: Findings from the 2007 Los Angeles Mommy and Baby (LAMB) Study. Matern Child Health J 18, 209–222 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-013-1256-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-013-1256-3