Abstract

Mounting evidence from clinic and convenience samples suggests that stress is an important predictor of adverse obstetric outcomes. Using a proposed theoretical framework, this review identified and synthesized the population-based literature on the measurement of stress prior to and during pregnancy in relation to obstetric outcomes. Population-based, peer-reviewed empirical articles that examined stress prior to or during pregnancy in relation to obstetric outcomes were identified in the PubMed and PsycInfo databases. Articles were evaluated to determine the domain(s) of stress (environmental, psychological, and/or biological), period(s) of stress (preconception and/or pregnancy), and strength of the association between stress and obstetric outcomes. Thirteen studies were evaluated. The identified studies were all conducted in developed countries. The majority of studies examined stress only during pregnancy (n = 10); three examined stress during both the preconception and pregnancy periods (n = 3). Most studies examined the environmental domain (e.g. life events) only (n = 9), two studies examined the psychological domain only, and two studies examined both. No study incorporated a biological measure of stress. Environmental stressors before and during pregnancy were associated with worse obstetric outcomes, although some conflicting findings exist. Few population-based studies have examined stress before or during pregnancy in relation to obstetric outcomes. Although considerable variation exists in the measurement of stress across studies, environmental stress increased the risk for poor obstetric outcomes. Additional work using a lifecourse approach is needed to fill the existing gaps in the literature and to develop a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms by which stress impacts obstetric outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Poor obstetric outcomes (e.g. low birthweight, pregnancy complications) are serious public health problems, accounting for over 40 % of all neonatal deaths and a substantial proportion of neurodevelopmental disabilities in the United States [1–3]. Mounting clinic-based evidence suggests that stress is an important risk factor for poor obstetric outcomes [4–13].

Theory suggests that stress is a process by which “environmental demands tax or exceed the adaptive capacity of an organism, resulting in psychological and biological changes that may place persons at risk for disease” [14]. Understanding how stress is operationalized across the lifecourse is necessary to fully investigate the mechanisms by which stress affects obstetric outcomes [15–17]. Despite the theoretical support for a multidimensional approach to the measurement of stress, the extent to which stress has been measured in population-based research on obstetric outcomes and how it has been operationalized in such studies remains unclear.

Therefore, the purpose of this review was threefold. First, we sought to identify studies that investigated the relationship between stress and obstetric outcomes in population-based samples. Second, we determined how stress had been operationalized in these studies, specifically in terms of domains (environmental, psychological, and biological) and time periods (preconception and prenatal) pertinent to obstetric outcomes. Finally, we summarized the strength of the association of stress with obstetric outcomes in these studies.

This review was guided by a conceptual framework that integrates several key theories, including a lifecourse developmental perspective [15, 18], social-ecological systems theory [19], stress theory [20], a multiple determinants of health perspective [21], and a framework of perinatal health [17]. Based on these theories, we propose that environmental stressors such as life events, daily hassles, or neighborhood or community factors have a cascading impact on an individual’s appraisal, biology, and subsequent level of adaptation. This process incorporates multiple domains of stress (e.g. environmental, psychological, and biological) and time periods in a woman’s life (e.g. preconception—encompassing the entire period prior to each pregnancy, including childhood, adolescence, and the interconception period; pregnancy; and postpartum) that are uniquely and cumulatively associated with health outcomes in the literature [7, 22–25]. This stress process is influenced by contextual effects (e.g. neighborhoods [26]) and occurs across the lifecourse.

Together, the stress process, context, and timing all impact women’s “health capital” at conception. Health capital “[encompasses] all the gains and losses in health over a lifetime,” [27] and is conceptualized as the culmination of biological, psychological and social experiences, exposures, and resources across the lifecourse and across generations. Maternal health capital is viewed as a lens through which stress contributes to a spectrum of health outcomes, such that women with more positive health capital will be less likely to experience poor obstetric and health outcomes attributable to stress.

The present study applies this model to examine how population-based studies have operationalized stress in relation to obstetric outcomes. Findings from this review have important implications for future research, policy, and practice as results provide evidence of gaps in the literature surrounding the measurement of stress.

Methods

Initial Search Strategy

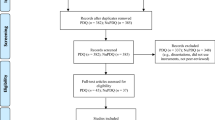

Relevant literature was identified through a systematic search of the PubMed and PsycInfo databases. Articles were initially selected if the following keywords appeared in the article title or abstract: “stress;” and either “prepregnancy,” “preconception,” “pregnancy,” “prenatal,” “antenatal,” “postnatal,” or “postpartum.” Filters limited articles to those published in English and conducted in human populations. The last search date was June 21, 2011. These search criteria identified 4,307 articles in PubMed and 1,536 articles in PsycInfo (Fig. 1).

Screening and Article Selection

A two-step process was used to select articles. First, articles were divided among the authors, and titles and abstracts were screened; articles that measured stress in the preconception, pregnancy, and/or postpartum periods were highlighted for further review (n = 612). Second, the authors examined full-text versions of all potential articles, dividing the articles among the authors. Articles were included if they: (1) were published during or after the year 2000 in a peer-reviewed journal; (2) explicitly measured stress in women before or during pregnancy and examined health-related outcomes that occurred during or after pregnancy; (3) included stress as a primary independent variable; and (4) used a population-based sample, defined as having been conducted in a sample that is representative of, and therefore generalizable to, a broader, well-defined population (such as a region or country) [28]. We selected literature from 2000 to present to review the most recent and relevant measures of maternal stress. After this initial review, the scope of the review was narrowed to include only studies that examined stress prior to or during pregnancy in relation to obstetric outcomes [specifically: pregnancy complications, non-live birth, preterm birth (PTB), very low birthweight, low birthweight (LBW), or small for gestational age (SGA)] in population-based samples in order to provide unbiased and generalizable estimates of effects [28]. Figure 1 provides additional information on the excluded studies.

Data Collection for Selected Studies

Four authors collected information from the full-text articles using a standardized data collection form. The information collected included: (1) the instrument or measure of stress employed in the study; (2) when the instrument was administered; (3) whether the instrument used had been validated (as reported in the article); and (4) the domains and periods assessed by each measure. Each study was examined twice; one author reviewed and resolved any discrepancies in classification via a careful re-examination of the manuscript. The magnitude and statistical significance of the findings were recorded, as well as details about the instrument used to measure stress in each study (e.g. the instruments’ reliability and validity).

Domains of stress were defined based on the conceptual framework as: environmental (e.g. life events, daily hassles, or natural disasters or catastrophes, such as death of a close relative); psychological (e.g. perceived stress); or biological (e.g. cortisol levels). Domains were categorized based on the question or measure used in the study. Measures that primarily asked about events or the occurrence of stressors were categorized as environmental, while those that primarily asked about participants’ perception or appraisal were categorized as psychological. The period was defined as preconception or pregnancy based on the time frame evaluated by the measure.

We evaluated the frequency of studies that measured stress in each period (preconception and/or pregnancy) and/or measured stress in each domain (environmental, psychological, and/or biological).

Results

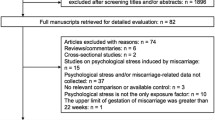

Thirteen studies were identified that examined the relationship between stress and obstetric outcomes in population-based samples (Table 1). Each of the identified studies occurred in one of four developed countries, with nearly half conducted in the U.S. While all of these studies examined stress during pregnancy, three (23.1 %) also incorporated a measure of stress during the preconception period. Most of the studies examined stress in the environmental domain (11 studies total, 84.6 %); for 9 studies (69.2 %), this was the only domain examined. No study examined the biological domain, and only two studies (15.4 %) explored both environmental and psychological domains. Figure 2 depicts the 13 studies by the period and domain of the measurement of stress.

Period and domain of stress measured in population-based studies examining the relationship between stress and obstetric outcomes (n = 13). Three studies assessed stress during the preconception and pregnancy periods, examining the environmental domain (Box A). Six studies examined the environmental domain during the pregnancy period only (Box B), two studies examined psychological stress during pregnancy only (Box C), and two studies examined both the environmental and psychological domains during the pregnancy period (Box D). No studies examined stress in the biological domain (Box E)

Table 2 presents a summary of the stress measures used in the reviewed studies and their associations with obstetric outcomes, specifically: (1) the studies’ operationalization of stress, including the data source, periods and domains used to assess stress, specific instruments used, and the instruments’ reliability (e.g. Cronbach’s alpha and/or test–retest reliability) if applicable; and (2) the measures’ associations with obstetric outcomes. No study investigated the relationship between stress and pregnancy complications. Additional information on the studies, including the variables included in the final adjusted models, are available as supplemental material (Appendix).

Operationalization of Stress

Three studies examined only environmental stress during the preconception and pregnancy periods (Fig. 2, Box A). These studies each operationalized stress as the exposure to an acute life event using the Danish National Registers. Two of these studies [29, 30] measured stress as the death or serious illness of a relative occurring within 6 months prior to pregnancy (preconception stressor) or during the trimesters of pregnancy (stressor during pregnancy). The third study operationalized preconception stress and stress during pregnancy as the death or first hospitalization for cancer or acute myocardial infarction in partners or children up to 485 days before pregnancy (analyzed as 0–5 months, 6–11 months, or 1 year to 485 days before pregnancy) or during each trimester of pregnancy, respectively [31].

Among the six studies that solely examined environmental stress during pregnancy (Fig. 2, Box B), three used the Modified Life Events Inventory (13 and 18 item versions) from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) [32–34]. Lu and Chen [32] and Nkansah-Amankra et al. [33] used principle components analysis to group events into four stress constructs (emotional, financial, spousal, and traumatic events); women who endorsed any item within these constructs were coded as having experienced stress. Whitehead et al. [34] estimated a threshold level of stressful life events (0, 2, or 5 events, depending on the analysis) and dichotomized women by whether they experienced stress above the threshold. Further, using administrative records, two studies operationalized stress as the death of the child’s father or a first-degree relative of the mother (using linked Swedish population registries) [35], or exposure to the 9/11 attacks during pregnancy (using birth certificate data) [36]. Finally, Zhu et al. [37] used two questions from the Danish National Birth Cohort that asked women about perceived job demand and control as indicators of stress during pregnancy; those who reported high demand and low control were recorded as having high job strain (Table 2).

Four studies incorporated measures of stress in the psychological domain (Fig. 2, Boxes C and D), two using the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS, 4 and 10 item versions) [38–40] as either a continuous summary score [38] or categorized into four groups (i.e. PSS-4: 4–8: low stress, 9–12: moderate stress, and 13–20: high stress) [39]. Two other studies used individual, unvalidated questions to measure psychological stress. Tegethoff et al. [41] operationalized stress using data from the Danish National Birth Cohort as a woman’s report of experiencing stress related to nine factors (e.g. housing circumstances or relationship to partner); responses were summed, and the continuous score was used in the analyses. Sable et al. [42] assessed psychological stress using one survey question from the Missouri Maternal and Infant Health Study (e.g. “In general, how often did you feel stress during your recent pregnancy?”); the measure was dichotomized as experiencing stress “almost always” versus “often,” “sometimes,” or “almost never.” In addition to measures of psychological stress during pregnancy, Ghosh et al. [39] and Sable et al. [42] also included measures of stress in the environmental domain during pregnancy (Fig. 2, Box D). Ghosh et al. [39] used data from the UCLA Environment and Pregnancy Outcomes Study, which included a six-item, unvalidated questionnaire of major life events that may have occurred during pregnancy, such as losing a home or job or having a personal friend or relative die. Women who reported one life event were recorded as having moderate life stress, while those who reported two or more events were recorded as having high life stress. Finally, Sable et al. [42] operationalized stress during pregnancy as a woman’s response to the question “During your most recent pregnancy, did any of the following events happen to you?” (e.g. close family member died, laid off or fired from job; yes/no); each event was analyzed individually.

Associations with Obstetric Outcomes

In general, the most consistent relationship observed among these studies was between preconception stress and adverse obstetric outcomes, including SGA and PTB (n = 3). In addition, environmental stress during pregnancy was consistently associated with SGA (n = 3) and LBW (n = 4). Evidence for the association between environmental stress during pregnancy and PTB was mixed, with three studies reporting a significant association and three studies reporting null results. Evidence for the association between perceived stress during pregnancy and obstetric outcomes was also inconsistent.

Women who reported preconception stress in the environmental domain (Fig. 2, Box A) were consistently and significantly more likely to experience PTB [29] and have a SGA infant [30, 31]. However, these studies reported mixed findings for the effect of environmental stress during pregnancy. One study [30] found that the exposure to environmental stress during pregnancy increased the risk of having a SGA infant (Trimester 1: AOR = 1.17; 95 % CI = [1.07–1.29]; Trimester 2: AOR = 1.24; 95 % CI = [1.13–1.36]; Trimester 3: AOR = 1.22; 95 % CI = [1.12–1.32]); while another [31] did not find a significant association at any trimester.

Exposure to environmental stress during pregnancy was significantly associated with an increased risk of PTB in half of the studies (Fig. 2, Box B) [33, 34, 36]. Interestingly, while Lu and Chen [32] reported no significant associations between exposure to environmental stressors during pregnancy and PTB, Nkansah-Amankra et al.’s study [33] revealed significant associations between emotional (AOR = 1.41; 95 % CI = [1.35–1.48]) and traumatic (AOR = 1.07; 95 % CI = [1.03–1.12]) stressors and the risk of PTB using multilevel modeling and the same dataset and operationalization of stress. Environmental stress during pregnancy was also associated with having an infant born with LBW [33, 35, 42] or SGA [35], but not with fetal loss, spontaneous abortion, or stillbirth [37].

Two studies examined stress in the psychological domain during pregnancy only (Fig. 2, Box C). One study reported that psychological stress during pregnancy, when measured as perceived stress associated with nine categories of stressors, was associated with shorter gestational length and increased offspring body size [41]. Conversely, Pryor et al. [38], who examined global perceived stress using the PSS, found no relationship between psychological stress during pregnancy and having a SGA baby.

Finally, two studies examined the association between stress measured by multiple domains and obstetric outcomes (Fig. 2, Box D). Ghosh et al. [39] found that high levels of perceived stress during pregnancy increased the risk of experiencing PTB, while moderate levels of perceived stress and exposure to environmental stress did not. Sable et al. [42] found that both environmental and psychological stress during pregnancy were associated with an increased risk of having a very LBW baby. However, in each study, the domains of stress were included in separate analyses, and the independent effect of each domain was not isolated.

Discussion

Using a comprehensive theoretical framework, this study identified and synthesized the population-based literature on the measurement of stress prior to and during pregnancy in relation to obstetric outcomes. We found that very few population-based studies examined multiple stress domains, operationalized stress across the lifecourse, or used prospective measures of stress. The association between stress and obstetric outcomes varied across these studies, possibly due to the different operationalizations of stress even within the same stress domains. However, compelling population-based evidence suggests that environmental stress before and during pregnancy is associated with an increased risk for poor obstetric outcomes.

Theory and empirical evidence highlight the importance of fully capturing stress over the course of a woman’s entire developmental trajectory (including early life, preconception, pregnancy, interconception, and intergenerational periods) to help evaluate her health capital at conception and subsequent risk for experiencing adverse obstetric outcomes [15, 32]. However, only three of the studies identified by this review evaluated stress at multiple time periods. Among these studies, the most consistent evidence was found for a relationship between preconception stress and poor obstetric outcomes. Therefore, continuing to focus research solely on stress during pregnancy may obscure important pathways leading to poor obstetric outcomes. Researchers have recently suggested that prevention strategies implemented prior to conception represent the greatest opportunity to further improve pregnancy outcomes [43]. Future studies should measure stress in multiple periods (including events in early childhood and adolescence) in order to isolate the effects of stress over time and to better inform when programmatic and policy interventions would be most effective.

Measuring multiple domains of stress is equally important in understanding how stress may influence obstetric outcomes [16]. Theory suggests that stress is a process by which environmental stimuli may overwhelm an individual’s coping resources [44], leading to the perception of stress and subsequent physiological responses (e.g. HPA axis activation) that attempt to regain homeostasis [45]. Evaluating only a single domain thus captures only a portion of the stress process. Future studies will need to employ comprehensive measures of stress that incorporate multiple domains to understand how this process unfolds to impact obstetric outcomes and identify points for intervention.

Furthermore, no study included in this review incorporated a biological measure of stress. As effective and minimally-invasive techniques continue to emerge (e.g. collecting blood spots using a finger stick procedure [46]), the incorporation of biological data has become more feasible on a population-level. Overall, studies that encompass multiple domains of stress over time, especially at the biological level, will be crucial in order to better understand the physiological pathways by which stress affects health outcomes.

In addition, the studies evaluated in this review used a wide array of measures to capture stress and controlled for a diverse array of covariates, limiting the comparability of these findings and potentially accounting for some of the conflicting results observed regarding obstetric outcomes. For example, an association was reported between environmental stress during pregnancy and PTB when environmental stress was measured objectively via administrative records [29], but not when measured retrospectively through a self-administered survey questionnaire [39]. In fact, the majority of studies utilized surveys administered during the postpartum period that asked women to recall the occurrence of life events during their pregnancy. Obtaining prospective assessments of maternal stress is therefore important, as recall bias may significantly affect the quality of the data.

We propose several recommendations for future research based on the gaps identified in this review. First, measurement of stress in women that is strongly grounded in both theory and empirical evidence is needed. As stress is a broad term that can be defined in numerous ways, and most studies in this review likely derived stress measures from available data in population-based surveys or national registers, future researchers should thoroughly understand their conceptualization of stress prior to operationalizing this complex construct. The conceptual framework presented may serve as a guide by which researchers operationalize stress in future research. Second, future research should adopt a lifecourse approach for the measurement of stress, especially given the relationship between preconception stress and obstetric outcomes. Third, researchers should strive to measure multiple domains of stress. Studies of obstetric outcomes should also consider using instruments designed to measure stressors related to pregnancy (e.g. stress regarding labor/delivery and the infant’s health [47–49]) that may not be captured in general stress measures.

Finally, more longitudinal population-based studies of stress and associated health outcomes are needed. Of the studies examined here, only two evaluated stress prospectively [37, 41], and neither of these examined stress at multiple time periods. Data from prospective representative cohorts are necessary in order to formulate consistent and generalizable evaluations of stress and to limit recall bias among participants. Although the burden of establishing and maintaining a longitudinal national cohort is acknowledged, these resources are necessary to facilitate future lifecourse research and to improve our understanding of the long-term effects of stress on health. Ongoing national policies and initiatives to support such studies are greatly needed.

Several potential limitations should be considered when interpreting our results. Although a comprehensive search of the literature was conducted to identify articles for inclusion, some relevant articles may have been missed. Nevertheless, the patterns revealed by this study are telling and unlikely to be impacted by such an oversight. In addition, we only included studies published since the year 2000, and different trends may have been observed during earlier time periods. However, as the complexity of research questions tends to grow over time, earlier research was unlikely to have taken a more nuanced approach to this question. Finally, our review was limited to studies published in English. As such, we may have missed population-based studies from countries where the experience and measurement of stress may have differed from the measures identified in this review.

Despite these potential limitations, this study provides a comprehensive review the measurement of stress in relation to obstetric outcomes in the population-based literature. Our findings indicate that significant gaps exist, including the lack of: (1) measurement of stress at multiple time points over the lifecourse; (2) incorporation of multiple domains of stress; and (3) prospective population-based studies. Emerging and existing population-based birth cohorts have the opportunity to fill these gaps through the appropriate choice of instruments implemented at multiple time periods over a woman’s life. Research in such samples would help identify women at high risk for poor obstetric outcomes and point to critical periods across the lifecourse where interventions may be the most effective. Most importantly, such work would be invaluable to our understanding of how stress impacts the immediate and long-term health of mothers, children, and future generations.

References

Heron, M. (2012). Deaths: Leading causes for 2008. National Vital Statistics Reports. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Vohr, B. R., Wright, L. L., Dusick, A. M., et al. (2000). Neurodevelopmental and functional outcomes of extremely low birth weight infants in the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network, 1993–1994. Pediatrics, 105, 1216–1226.

Bhutta, A. T., Cleves, M. A., Casey, P. H., et al. (2002). Cognitive and behavioral outcomes of school-aged children who were born preterm: a meta-analysis. JAMA, 288, 728–737.

Arck, P. C., Rucke, M., Rose, M., et al. (2008). Early risk factors for miscarriage: a prospective cohort study in pregnant women. Reproductive Biomedicine Online, 17, 101–113.

Dole, N., Savitz, D. A., Hertz-Picciotto, I., et al. (2003). Maternal stress and preterm birth. American Journal of Epidemiology, 157, 14–24.

Copper, R. L., Goldenberg, R. L., Das, A., et al. (1996). The preterm prediction study: Maternal stress is associated with spontaneous preterm birth at less than thirty-five weeks’ gestation. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 175, 1286–1292.

Gennaro, S., & Hennessy, M. D. (2003). Psychological and physiological stress: Impact on preterm birth. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 32, 668–675.

Nordentoft, M., Lou, H. C., Hansen, D., et al. (1996). Intrauterine growth retardation and premature delivery: The influence of maternal smoking and psychosocial factors. American Journal of Public Health, 86, 347–354.

Paarlberg, K. M., Vingerhoets, J., Passchier, J., et al. (1999). Psychosocial predictors of low birthweight: A prospective study. BJOG, 106, 834–841.

Pagel, M. D., Smilkstein, G., Regen, H., et al. (1990). Psychosocial influences on new born outcomes: A controlled prospective study. Social Science and Medicine, 30, 597–604.

Pritchard, C., & Teo Mfphm, P. (1994). Preterm birth, low birthweight and the stressfulness of the household role for pregnant women. Social Science and Medicine, 38, 89–96.

Rondo, P., Ferreira, R., Nogueira, F., et al. (2003). Maternal psychological stress and distress as predictors of low birth weight, prematurity and intrauterine growth retardation. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 57, 266–272.

Jacobsen, G., Schei, B., & Hoffman, H. (1997). Psychosocial factors and small-for-gestational-age infants among parous Scandinavian women. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. Supplement, 165, 14–18.

Cohen, S., Kessler, R. C., & Gordon, L. U. (1995). Strategies for measuring stress in studies of psychiatric and physical disorders. In S. Cohen, R. C. Kessler, & L. U. Gordon (Eds.), Measuring stress: A guide for health and social scientists (p. 3). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lu, M., & Halfon, N. (2003). Racial and ethnic disparities in birth outcomes: A life-course perspective. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 7, 13–30.

Dunkel-Schetter, C., & Glynn, L. (2010). Stress in pregnancy: Empirical evidence and theoretical issues to guide interdisciplinary research. In: R. Contrada & A. Baum (Eds.), Handbook of stress science. New York: Springer.

Misra, D., Guyer, B., & Allston, A. (2003). Integrated perinatal health framework. A multiple determinants model with a life span approach. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 25, 65–75.

Halfon, N., & Hochstein, M. (2002). Life course health development: An integrated framework for developing health, policy, and research. Milbank Quarterly, 80, 433–479.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

House, J. S. (1974). Occupational stress and coronary heart disease: A review and theoretical integration. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 15, 12–27.

Evans, R. G., & Stoddart, G. L. (1990). Producing health, consuming health care. Social Science and Medicine, 31, 1347–1363.

Witt, W. P., Wisk, L. E., Cheng, E. R., et al. (2011). Preconception mental health predicts pregnancy complications and adverse birth outcomes: A national population-based study. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 16, 1525–1541.

Harville, E., Xiong, X., & Buekens, P. (2010). Disasters and perinatal health: A systematic review. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey, 65, 713–728.

Witt, W. P., Wisk, L. E., Cheng, E. R., et al. (2011). Poor prepregnancy and antepartum mental health predicts postpartum mental health problems among US women: A nationally representative population-based study. Women’s Health Issues, 21, 304–313.

Federenko, I., & Wadhwa, P. (2004). Women’s mental health during pregnancy influences fetal and infant developmental and health outcomes. CNS Spectrums, 9, 198–206.

Metcalfe, A., Lail, P., Ghali, W. A., et al. (2011). The association between neighbourhoods and adverse birth outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of multi-level studies. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 25, 236–245.

Blaxter, M. (2010). Health (key concepts). Cambridge: Polity Press.

Szklo, M. (1998). Population-based cohort studies. Epidemiologic Reviews, 20, 81–90.

Khashan, A. S., McNamee, R., Abel, K. M., et al. (2009). Rates of preterm birth following antenatal maternal exposure to severe life events: A population-based cohort study. Human Reproduction, 24, 429–437.

Khashan, A. S., McNamee, R., Abel, K. M., et al. (2008). Reduced infant birthweight consequent upon maternal exposure to severe life events. Psychosomatic Medicine, 70, 688–694.

Precht, D. H., Andersen, P. K., & Olsen, J. (2007). Severe life events and impaired fetal growth: A nation-wide study with complete follow-up. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 86, 266–275.

Lu, M., & Chen, B. (2004). Racial and ethnic disparities in preterm birth: The role of stressful life events. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 191, 691–699.

Nkansah-Amankra, S., Luchok, K. J., Hussey, J. R., et al. (2010). Effects of maternal stress on low birth weight and preterm birth outcomes across neighborhoods of South Carolina, 2000–2003. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 14, 215–226.

Whitehead, N., Hill, H., Brogan, D., et al. (2002). Exploration of threshold analysis in the relation between stressful life events and preterm delivery. American Journal of Epidemiology, 155, 117–124.

Class, Q., Lichtenstein, P., Långström, N., et al. (2011). Timing of prenatal maternal exposure to severe life events and adverse pregnancy outcomes: A population study of 2.6 million pregnancies. Psychosomatic Medicine, 73, 234–241.

Eskenazi, B., Marks, A., Catalano, R., et al. (2007). Low birthweight in New York City and upstate New York following the events of September 11th. Human Reproduction, 22, 3013–3020.

Zhu, J. L., Hjollund, N. H., Andersen, A. M., et al. (2004). Shift work, job stress, and late fetal loss: The national birth cohort in Denmark. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 46, 1144–1149.

Pryor, J., Thompson, J., Robinson, E., et al. (2003). Stress and lack of social support as risk factors for small-for-gestational-age birth. Acta Paediatrica, 92, 62–64.

Ghosh, J. K., Wilhelm, M. H., Dunkel-Schetter, C., et al. (2010). Paternal support and preterm birth, and the moderation of effects of chronic stress: a study in Los Angeles county mothers. Archives of Womens Mental Health, 13, 327–338.

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 385–396.

Tegethoff, M., Greene, N., Olsen, J., et al. (2010). Maternal psychosocial adversity during pregnancy is associated with length of gestation and offspring size at birth: Evidence from a population-based cohort study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 72, 419–426.

Sable, M., & Wilkinson, D. (2000). Impact of perceived stress, major life events and pregnancy attitudes on low birth weight. Family Planning Perspectives, 32, 288–294.

Atrash, H. K., Johnson, K., Adams, M., et al. (2006). Preconception care for improving perinatal outcomes: The time to act. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 10, S3–S11.

Cohen, S., & Williamson, G. M. (1987). Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In S. Spacapan & S. Oskamp (Eds.), The social psychology of health (pp. 31–49). Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

McEwen, B. S. (1998). Stress, adaptation, and disease: Allostasis and allostatic load. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 840, 33–44.

McDade, T. W., Williams, S., & Snodgrass, J. J. (2007). What a drop can do: dried blood spots as a minimally invasive method for integrating biomarkers into population-based research. Demography, 44, 899–925.

Affonso, D. D., Liu-Chiang, C. Y., & Mayberry, L. J. (1999). Worry: Conceptual dimensions and relevance to childbearing women. Health Care for Women International, 20, 227–236.

Lobel, M., Cannella, D. L., Graham, J. E., et al. (2008). Pregnancy-specific stress, prenatal health behaviors, and birth outcomes. Health Psychology, 27, 604–615.

Misra, D., O’Campo, P., & Strobino, D. (2001). Testing a sociomedical model for preterm delivery. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 15, 110–122.

Acknowledgments

This project has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services (Contract Nos HHSN275200503396C and HHSN275201100014C, National Children’s Study Wisconsin Study Center (PI: M. Durkin and S. Leuthner). The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Additional funding for this research was provided by a grant from the Health Disparities Research Scholars Program (FW; T32 HD049302; PI: G. Sarto). We would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Witt, W.P., Litzelman, K., Cheng, E.R. et al. Measuring Stress Before and During Pregnancy: A Review of Population-Based Studies of Obstetric Outcomes. Matern Child Health J 18, 52–63 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-013-1233-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-013-1233-x