Abstract

To assess the association between lifetime violence victimization and self-reported symptoms associated with pregnancy complications among women living in refugee camps along the Thai-Burma border. Cross-sectional survey of partnered women aged 15–49 years living in three refugee camps who reported a pregnancy that resulted in a live birth within the past 2 years with complete data (n = 337). Variables included the lifetime prevalence of any violence victimization, conflict victimization, intimate partner violence (IPV) victimization, self-reported symptoms of pregnancy complications, and demographic covariates. Logistic generalized estimating equations, accounting for camp-level clustering, were used to assess the relationships of interest. Approximately one in six women (16.0 %) reported symptoms related to pregnancy complications for their most recent birth within the last 2 years and 15 % experienced violence victimization. In multivariable analyses, any form of lifetime violence victimization was associated with 3.1 times heightened odds of reporting symptoms (95 % CI 1.8–5.2). In the final adjusted model, conflict victimization was associated with a 3.0 increase in odds of symptoms (95 % CI 2.4–3.7). However, lifetime IPV victimization was not associated with symptoms, after accounting for conflict victimization (aOR: 1.8; 95 % CI 0.4–9.0). Conflict victimization was strongly linked with heightened risk of self-reported symptoms associated with pregnancy complications among women in refugee camps along the Thai-Burma border. Future research and programs should consider the long-term impacts of conflict victimization in relation to maternal health to better meet the needs of refugee women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Globally, maternal mortality remains a key health and human rights concern as approximately 273,500 women died in 2011 due to pregnancy-related causes [1]. Countries affected by war often have the highest rates of maternal mortality [2, 3] as armed conflicts interrupt and destroy health services and often occur within countries with poor preexisting maternal health indicators [3]. Burma (Myanmar) is one such country with a decades-long conflict and an estimated maternal mortality ratio (MMR) of 464 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 2011 [1]. The MMR of Burma is well-above that of neighboring Thailand’s rate of 40 maternal deaths, in addition to the worldwide average MMR of 202 [1].

Mortality due to pregnancy-related causes in Burma may be even higher among minority or displaced populations [4] and estimates among ethnic communities affected by conflict in eastern Burma conclude that 27 % of adult female deaths were due to such causes [5]. Critically, maternal mortality represents a small component of maternal health, as for every maternal death, countless more women experience related morbidities [6], which may include anemia, [7] hypertensive disorders, vaginal bleeding, or abdominal pain [8]. Attention to pregnancy complications in terms of women’s outcomes may be directly related not only to maternal mortality but also to long-term morbidity, which can have detrimental social and economic impacts for the woman, her family, and community [9, 10].

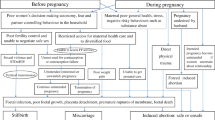

Women’s experiences of violence victimization and human rights violations may be critical components in understanding maternal health morbidity [11, 12]. Such victimization experiences may confer increased risk of pregnancy morbidity due to direct physical injuries, negative health behaviors resulting from adverse coping mechanisms related to trauma, or poor mental health [13]. Consideration of victimization is particularly important among conflict-affected women along the Thai-Burma border, as human rights violations have been previously associated with increased risk of anemia among internally displaced women in eastern Burma [14]. In addition, residing in communities affected by armed conflict and political violence has also been associated with complications during pregnancy [15]. Moreover, violence against women (VAW) in the context of armed conflict, and specifically sexual violence during the conflict perpetrated by non-partners, has been linked to a range of reproductive health concerns such as infertility, chronic abdominal pain, and abnormal vaginal bleeding [16]. While previous studies have investigated other reproductive and maternal health indicators and programming among conflict-affected populations, [14, 17–19] there remains limited understanding of the relationship between conflict victimization and self-reported symptoms associated with pregnancy complications among refugee women from Burma.

Equally imperative to consider, in addition to understanding the relationship between non-partner perpetrated conflict victimization and such symptoms, are experiences of violence victimization perpetrated by a woman’s partner. Intimate partner violence (IPV), which includes physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, has been associated with a range of negative reproductive and child health outcomes in a variety of populations [11, 12, 20–22]. Moreover, alarmingly high frequencies of IPV victimization have been documented among women affected by armed conflict or political violence [23], as both partner-perpetrated and non-partner-perpetrated forms of violence may be rooted in unequal gender norms [24, 25]. Qualitative research provides evidence that women who have experienced conflict victimization, and in particular conflict-related sexual violence, may be particularly susceptible to partner-perpetrated violence victimization in the aftermath of armed conflict or political violence [24]. Understanding of both forms of violence victimization and symptoms related to pregnancy-related morbidity may be critically important for effectively addressing maternal health among conflict-affected women.

Given the potentially high rates of individual experiences of violence victimization among conflict-affected women and the limited understanding of how these factors relate to maternal health, the objectives of the present analysis were threefold: (1) describe the prevalence of self-reported symptoms associated with pregnancy complications among refugee women along the Thai-Burma border; (2) assess the association between any form of lifetime violence victimization and symptoms during the most recent pregnancy; and (3) determine the specific relationships between symptoms and experiences of lifetime conflict victimization and lifetime IPV victimization in order to guide maternal health programmatic efforts among refugee women.

Methods

The current investigation draws on cross-sectional survey data from the Reproductive Health Assessment Toolkit for Conflict-Affected Women [26]. This survey was developed by the Division of Reproductive Health at the Centers for Disease Control and was implemented in three American Refugee Committee (ARC) refugee camps where ARC provides maternal health services (Umpiem Mai, Nu Po, and Ban Don Yang) in early 2008 along the Thai-Burma border. All women aged 15–49 years were eligible to participate. A random sampling methodology was utilized to select women from current demographic household registries, within each camp, that were maintained by ARC.

A generic informed consent form was read verbatim at the participant’s home regarding a survey on women’s health; a second informed consent was given before the survey in a private location and included a discussion of violence. Surveys were administered by trained ARC refugee staff in a central location in each of the three camps. Questionnaires were translated into Karen and Burmese and were language-matched to the interview staff and participant. The Harvard School of Public Health Human Subjects Research Committee found the secondary analysis of de-identified programmatic data exempt.

All items were self-reported. Demographics examined include age, ethnicity, religion, literacy, and partnership status; all items were drawn from the toolkit. Prior adverse pregnancy outcome was operationalized as a binary yes/no variable and was included as it relates to maternal care utilization [27] and could account for residual variation. The variable was a summary variable comprised of two questions: (1) “Have you lost a baby before completing the sixth month of pregnancy (spontaneous or induced abortions)” and (2) “Have you had any sons or daughters who were born dead after completing 6 months of pregnancy (stillborn).”

The exposure, conflict victimization, was assessed in an eight item scale [26]. All women were asked, “During the conflict, were you subjected to any of these forms of violence by people outside of your family? These acts could have been done by anyone who is not a family member.” Types of violence queried included being physically hurt, threatened with a weapon, being shot at or stabbed, detainment against will, subjected to improper sexual comments, forced to remove clothing, subjected to unwanted kissing or touching, and forced or threatened with harm to have sex. The variable conflict victimization is a summary, binary variable in which any positive response to an item was coded as experiencing during conflict victimization and was selected due to the low frequencies of more nuanced exposure variables. Women who responded “don’t know” to an item were coded as not experiencing that form of violence for conservative estimates.

Lifetime emotional, physical, or sexual IPV victimization was assessed via a four item scale among women who ever reported having a partner. Types of violence included forbidding the women to see others, threatening with a weapon, physical violence, and threatened or forced to have sex even when she did not want to [26]. Any affirmative response was coded as experiencing lifetime IPV in the final summary, binary variable; all “don’t know” responses were coded as not experiencing that form of violence.

The variable any lifetime violence victimization is a summary variable where any positive response to lifetime conflict victimization or lifetime IPV victimization was coded as experiencing any violence victimization. Descriptive statistics regarding any affirmative response to any item for either conflict victimization or intimate partner violence were summed to assess a dose response relationship with self-reported pregnancy complications in descriptive analyses.

Questions about self-reported symptoms associated with pregnancy complications were asked of all women who reported a live birth or stillbirth within the last 2 years; all questions were in reference to the most recent pregnancy. Symptoms were assessed through a binary item, “Thinking back about that pregnancy, before you started or went into labor, did you have a problem or complication during pregnancy (not labor or delivery)?” If yes, respondents were then asked the types of problems or complications they had and if they sought medical help. Self-reported symptoms included in the follow-up items were: feeling weak or tired, severe abdominal pain, bleeding from vagina, fever, swelling of hands and face, blurred vision, or other complications. Women who reported stillbirths (n = 5) were removed from analyses given their small number in order to only examine the relationships of interest to pregnancies that resulted in a live birth.

All analyses were conducted in SAS 9.1. [28] Descriptive statistics were utilized to describe the frequencies of pregnancy complications with any lifetime violence victimization, lifetime conflict victimization, lifetime IPV victimization and covariates. Unadjusted and adjusted generalized estimating equations (GEEs) were used to assess the relationship between these forms of violence victimization and pregnancy complications and were chosen to adjust for potential clustering at the camp level. All statistical significance levels were set at the α < 0.05 level.

Results

A total of 1,242 women were asked to participate in the survey and 1,223 (98 %) completed the survey. Women who reported at least one pregnancy in the past 2 years were asked about their pregnancy history and outcomes (n = 400). Of the women who reported a pregnancy in the past 2 years, 19 women reported a spontaneous abortion, 5 reported stillbirths, and 3 women had missing pregnancy outcome data and were not included in the analysis (0 women reported an induced abortion) (n = 373). The analysis was further restricted to those women who reported having a partner or were married and had complete data for the variables of interest (n = 337).

The median age of respondents was 27.0 years (range 16–47 years). Over three-quarters were of Karen ethnicity and the majority of women were Christian (Table 1). Less than half of women were able to read easily. Approximately one in five women reported having a spontaneous or induced abortion or stillbirth among previous pregnancies and almost one in six women reported experiencing any form of violence throughout their lifetime. Nearly one in ten women reported lifetime conflict victimization and slightly less reported lifetime IPV victimization. Half of the women who reported both conflict and IPV victimization also reported symptoms, while 30.4 % of women who reported only conflict victimization reported symptoms and 21.1 % of women who reported only lifetime IPV victimization reported symptoms (Table 2). Approximately one-third of women who reported one type of violent event reported symptoms (Table 2).

Overall, 16.0 % of women reported symptoms during their last pregnancy that ended in a live birth and over 90 % of these sought medical attention. The most common form of pregnancy complication was feeling very weak or tired (Table 3). Women who experienced any form of violence victimization had 2.9 times higher odds of reported symptoms in the unadjusted analyses, compared to those that experienced no victimization (95 % CI 1.4–6.1) (Table 4). Lifetime report of conflict victimization was associated with a 3.6 times higher odds of reporting symptoms (95 % CI 1.9–6.6). In the unadjusted analyses, lifetime IPV victimization was also associated with higher odds of pregnancy complications, although this association did not reach statistical significance (OR 2.6; 95 % CI 0.7–9.5). Higher odds of symptoms were also associated with having a previous abortion or stillbirth (OR 2.2; 95 % CI 1.7–3.0) and not being able to read easily (OR 1.9; 95 % CI 1.4–2.6). Women who were 25–34 years old also had elevated odds of symptoms (OR 2.1; 95 % CI 1.2–3.5), compared to 15–24 year olds.

After accounting for covariates, any form of violence victimization was associated with 3.1 times higher odds of symptoms, compared to women who did not report any violence victimization (95 % CI 1.8–5.2) (Table 5). In the final model, after accounting for lifetime IPV victimization and covariates, women who experienced conflict victimization were 3.0 times more likely to report symptoms, compared to women who did not report conflict violence (95 % CI 2.4–3.7). However, after accounting for covariates and experiences of conflict victimization, lifetime IPV victimization was not statistically significantly associated with symptoms (aOR: 1.8; 0.4–9.0). An interaction term between conflict victimization and IPV victimization was not statistically significantly associated with symptoms (not shown). Reports of previous abortion or stillbirth were associated with a 1.6 times higher odds of reporting symptoms during the most recent pregnancy (95 % CI 1.02–2.6). Age and literacy was not associated with symptoms during the last pregnancy that resulted in a live birth in the final adjusted models.

Discussion

Overall, nearly one in six women (15.4 %) residing in refugee camps along the Thai-Burma border reported some form of violence victimization throughout their lifetime. Among women who did not experience victimization, approximately 13 % reported symptoms related to pregnancy complications. However, among those who did report violence victimization, almost one in three women reported symptoms. Importantly, over 90 % of women in our sample who reported pregnancy complication symptoms sought care from health clinics. Such findings underscore the importance of a comprehensive, multisectoral response, including integration of reproductive health and gender-based violence prevention and protection services [29]. Efforts must be rigorously evaluated to address the dual burden of pregnancy-related morbidity and violence against women.

Understanding increased risk of symptoms related to pregnancy complications among women who have experienced conflict victimization may offer an opportunity to target reproductive health programs [30] and highlights the need for violence training and education of health staff to effectively meet the needs of survivors [31]. Specific examples within humanitarian programming may include strengthening timely provision of clinical management of sexual violence and ensuring family planning and psychosocial services are provided to survivors. Along the Thai-Burma border, organization-based staff within camps should coordinate response and prevention efforts regarding pregnancy complications with other stakeholders, including the formal Thai health system [32]. Further, a recent analysis of maternal mortality trends among refugee populations on the Thai-Burma border documented that although the MMR is declining overall among refugee women, ample opportunities still exist to target women presenting with anemia or other modifiable factors that were found to be statistically associated with increased risk of maternal death [33].

While the analyses focused on a refugee population, additional implications persist for women who have also been affected by conflict violence within Burma or for refugee women who may repatriate in the future. This is particularly relevant given the opening of Burma to international aid organizations [34] and the formulation of strategic policies and programs to improve maternal health. These policies and programs should address the conflict-related experiences women have had as a mechanism to improve their pregnancy-related health, in addition to the overall establishment and improvement of reproductive health services [35]. As women in eastern Burma may have borne the preponderance of conflict victimization compared to other parts of the country, combined with a high maternal mortality ratio among ethnic minority women, [4] policies and programs must address these dual burdens. Maternal health programs should be scaled-up equitably and combined with programs to mitigate the negative effects of violence and conflict on women, within these regions.

Previous investigations have also documented that adverse mental and physical health consequences, including detrimental reproductive health issues, are associated with conflict-related sexual violence [16]. While our exposure of conflict victimization was a summary variable of physical, psychological, and sexual violence related to the conflict, we found a three-fold increase in odds of symptoms among women who have experienced conflict victimization, compared to women who did not experience such violence. These findings extend previous work documenting the negative effects of conflict related violence in regards to pregnancy health implications of such violence victimization. Additional research should examine hypothesized pathways through which conflict victimization and pregnancy complications symptoms are linked, including injuries, mental health, or negative coping behaviors among women as a result of victimization [13]. While experiences of conflict victimization were related to increased risk of symptoms, approximately 70 % of women who reported symptoms did not experience any victimization captured in the scale. Therefore, access to maternal health care services for all refugee women must be ensured to improve population level health.

The association between lifetime IPV victimization was not statistically significantly associated with symptoms among these refugee women along the Thai-Burma border. The lack of association is inconsistent with previous literature which has documented clear connections with negative maternal and neonatal health outcomes and such victimization [11, 12]. Limited sample size and statistical power may partially explain this contradictory finding, together with the use of our outcome measure, self-reported symptoms related to pregnancy complications. We also restricted our analyses to women who had a live birth in the analyses; the relationship between violence victimization and spontaneous/induced abortion or stillbirth may be different, but we were not able to assess the relationship due to small sample size of other outcomes in the data. We were also not able to assess the relationship between past-year IPV and symptoms, as the maternal health module was asked of women who reported a birth in the last 2 years and it would not be possible to establish temporality.

Limitations of the study should be considered in the interpretation of findings. First, experiences of violence victimization may be under-reported due to its sensitive and stigmatizing nature. We also do not have information regarding when conflict victimization or lifetime IPV victimization occurred in relation to the woman’s most recent pregnancy. Second, our outcome indicators are self-reported and measured non-specific pregnancy complication symptoms. Although this questionnaire has been derived from well-established questionnaires and pretested in similarly poorly educated populations [[26],] the validity of these self-reports is unknown. In other studies, the validity of such reports have been found to be limited, although the measures of validity and recall periods varied compared to our study [36, 37]. Future refugee camp-based research should focus on enhancing the validity of self-report (as it may be the only information available) through comparisons of medical records or other approaches to provide a richer understanding. The findings of such validity assessments may be extended to other conflict-affected populations, such as internally displaced persons or those in crisis settings, which do not readily have access to medical records. However, our point estimates of the associations between violence victimization and self-reported symptoms related to pregnancy complications would not be biased by the self-reported nature of our outcome, assuming random error, as such error would only affect the width of the confidence intervals around the estimate [38]. Third, our research focused on live births (the 24 women with spontaneous abortions or still births were considered too small for statistical analyses) so extrapolation to the relationships between victimization and symptoms among pregnancies resulting in other birth outcomes should be limited. Future research should examine other pregnancy-related outcomes, in addition to symptoms associated with complications, including induced abortions and stillbirths, intergenerational associations between conflict victimization, pregnancy-related morbidities, and child health outcomes. Finally, due to the cross-sectional design of the study we cannot make causal inferences nor account for all unmeasured confounding.

Despite these limitations, the study offers many strengths including a probability-based sample of a unique population of conflict-affected women. In addition, symptoms of pregnancy complications are reported for the most recent pregnancy within the last 2 years which may limit recall bias. Future research should consider the long-term and indirect impacts of conflict-related victimization from a programmatic, public health research, and human rights perspective in relation to maternal health outcomes to better meet the reproductive health needs of conflict-affected women and to capture the full cost of conflict on women of reproductive age. Maternal health and violence programming should continue expanding multi-sectoral efforts to address the health and psychosocial needs of conflict-affected women in protracted refugee settings.

References

Lozano, R., Wang, H., Foreman, K. J., Rajaratnam, J. K., Naghavi, M., Marcus, M. R., et al. (2011). Progress toward millennium development goals 4 and 5 on maternal and child mortality: An updated systematic analysis. Lancet, 378, 1139–1165.

Austin, J., Guy, S., Lee-Jones, L., McGinn, T., & Schlecht, J. (2008). Reproductive health: a right for refugees and internally displaced persons. Reproductive Health Matters, 16, 10–21.

Al Gasseer, N., Dresden, E., Keeney, G. B., & Warren, N. (2004). Status of women and infants in complex humanitarian emergencies. Journal of Midwifery and Womens Health, 49, 7–13.

Back Pack Health Worker Team. (2010). Diagnosis critical: Health and human rights in Eastern Burma. Thailand: Maesot.

Lee, T. J., Mullany, L. C., Richards, A. K., Kuiper, H. K., Maung, C., & Beyrer, C. (2006). Mortality rates in conflict zones in Karen, Karenni, and Mon states in eastern Burma. Tropical Medicine and International Health, 11, 1119–1127.

Koblinsky, M. (1999). Beyond maternal mortality—magnitude, interrelationship and consequences of women’s health, pregnancy-related complications, and nutritional status on pregnancy outcome. International journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 48, S21–S32.

Gangopadhyay, R., Karoshi, M., & Keith, L. (2011). Anemia and pregnancy: A link to maternal chronic diseases. International Journal of Gynecology, 115, S11–S15.

World Health Organization. (2000). Managing complications in pregnancy and childbirth: A guide for midwives and doctors. Geneva: WHO.

Hardee, K., Gay, J., & Blanc, A. K. (2012). Maternal morbidity: Neglected dimension of safe motherhood in the developing world. Global Public Health, 7, 603–617.

Ivengar, K., Yadav, R., & Sen, S. (2012). Consequences of maternal complications in women’s lives in the first postpartum year: A prospective cohort study. Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition, 30, 226–240.

Sarkar, N. N. (2008). The impact of intimate partner violence on women’s reproductive health and pregnancy outcome. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 28, 266–271.

Campbell, J. C. (2002). The health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet, 359, 1331–1336.

Rodgers, C. S., Lang, A. J., Twamley, E. W., et al. (2003). Sexual trauma and pregnancy: A conceptual framework. Journal of Women’s Health, 12, 961–970.

Mullany, L. C., Lee, C. I., Yone, L., Paw, P., Oo, E. K. S., Maung, C., et al. (2008). Access to essential maternal health interventions and human rights violations among vulnerable communities in Eastern Burma. PLoS Medicine, 5, 1689–1698.

Zapata, B. C., Rebolledo, A., Atalah, E., Newman, B., & King, M. C. (1992). The influence of social and political violence on the risk of pregnancy complications. American Journal of Public Health, 82, 685–690.

Kinyanda E, Musisi S, Biryabarema C, Ezati I, Oboke H, Ojiambo-Ochieng R, Were-Oguttu J, Levin J, Grosskurth H, Walugembe J. (2010). War related sexual violence and it’s medical and psychological consequences as seen in Kitgum, Northern Uganda: A cross-sectional study. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 10, 1–8.

Bartlett, L. A., Jamieson, D. J., Kahn, T., Sultana, M., Wilson, H. G., & Duerr, A. (2002). Maternal mortality among Afghan refugees in Pakistan, 1999–2000. Lancet, 359, 643–649.

Jamieson, D. J., Meikle, S. F., Hills, S. D., Mtsuko, D., Mawji, S., & Duerr, A. (2000). An evaluation of poor pregnancy outcomes among Burundian refugees in Tanzania. Journal of the American Medical Association, 283, 397–402.

Howard N, Woodward A, Souare Y, Kollie S, Blankhart D, von Roenne A, Borchert M. (2011). Reproductive health for refugees by refugees in Guinea III: Maternal health. Conflict and Health, 5, 1–8.

Chambliss, L. R. (2008). Intimate partner violence and its implication for pregnancy. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology, 51, 385–397.

Coker, A. L., Smith, P. H., Bethea, L., King, M. R., & McKeown, R. E. (2000). Physical health consequences of physical and psycholgical intimate partner violence. Archives of Family Medicine, 9, 451–457.

Ellsberg, M., Jansen, H. A. F. M., Heise, L., Watts, C. H., & Garcia-Moreno, C. (2008). WHO Multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women study team. Intimate partner violence and women’s physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence: an observational study. Lancet, 371, 1165–1172.

Stark, L., & Ager, A. (2011). A systematic review of prevalence studies of gender-based violence in complex emergencies. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, 12, 127–134.

Annan, J., & Brier, M. (2010). The risk of return: intimate partner violence in Northern Uganda’s armed conflict. Social Science and Medicine, 70, 152–159.

Heise, L. L. (1998). Violence against women: an integrated, ecological framework. Violence against Women, 4, 262–290.

Division of Reproductive Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Coordinating Center for Health Promotion, et al. (2007). Reproductive health assessment toolkit for conflict-affected women. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control.

Dhakal, S., van Teijlingen, E., Raja, E. A., & Dhakal, K. B. (2011). Skilled care at birth among rural women in Nepal: Practice and challenges. Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition, 29, 371–378.

Miller, E., Jordan, B., Levenson, R., & Silverman, J. G. (2010). Reproductive coercion: Connecting the dots between partner violence and unintended pregnancy. Contraception, 81, 457–459.

Silverman, J. G., Gupta, J., Decker, M. R., Kapur, N., & Raj, A. (2007). Intimate partner violence and unwanted pregnany, miscarriage, induced abortion, and stillbirth among a national sample of Bangladeshi women. Bangladesh Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 114, 1246–1252.

Hynes, M., Sheik, M., Wilson, H. G., & Spiegel, P. B. (2002). Reproductive health indicators and outcomes among refguee and internally displaced persons in postemergency phase camps. JAMA, the Journal of the American Medical Association, 288, 595–603.

Hyder, A. A., Noor, Z., & Tsui, E. (2007). Intimate partner violence among Afghan women living in refugee camps in Pakistan. Social Science and Medicine, 64, 1536–1547.

Hobstetter, M., Walsh, M., Leigh, J., Lee, C. I., Sietstra, C., & Foster, A. M. (2012). Separated by borders, united in need: An assessment of reproductive health on the Thailand-Burma border. Cambridge, MA: Ibis Reproductive Health.

Decker, M. R., Miller, E., Kapur, N., Gupta, J., Raj, A., & Silverman, J. G. (2008). Intimate partner violence and sexually transmitted disease symptoms in a national sample of married Bangladeshi women. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, 100, 18–23.

Saha, S. R. (2011). Working through ambiguity: International NGOs in Myanmar. Cambridge, MA: The Hauser Center for Nonprofit Organizations, Harvard University.

Bartlett, L., Aitken, I., Smith, J. M., Thomas, L. J., Rosen, H. E., Tappis, H., et al. (2012). Addressing maternal health in emergency settings. In J. Hussein, A. McCaw-Binns, & R. Webber (Eds.), Maternal and perinatal health in developing countries. Oxfordshire: CABI International.

Sloan, N. L., Amoaful, E., Arthur, P., Winikoff, B., & Adjei, S. (2001). Validity of women’s self-reported obstetric complications in rural Ghana. Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition, 19, 45–51.

Souza, J. P., Cecatti, J. G., Pacagnella, R. C., Giavorotti, T. M., Parpinelli, M. A., Camargo, R. S., et al. (2010). Development and validation of a questionnaire to identify sever maternal morbidity in epidemiological surveys. Reproductive Health, 7, 1–9.

Fox, J. (1997). Applied regression analysis, linear models, and related methods. London: Sage Publications.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the American Refugee Committee, specifically Gary Dahl, Damarice Ager, Yoriko Jinno, Lara Hendy, and Catherine Carlson, and all the refugee staff, for survey leadership and implementation. Falb’s time was partially supported by MCHB grant 5T76 MC 00001(formerly MCJ201).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Falb, K.L., McCormick, M.C., Hemenway, D. et al. Symptoms Associated with Pregnancy Complications Along the Thai-Burma Border: The Role of Conflict Violence and Intimate Partner Violence. Matern Child Health J 18, 29–37 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-013-1230-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-013-1230-0