Abstract

The objectives of this study were to develop an algorithm using government-collected administrative data to identify prenatally drug-exposed infants (DEI) and determine the percent who were referred to and eligible for Part C Early Intervention (EI) in Massachusetts. Data from the population-based Pregnancy to Early Life Longitudinal (PELL) Data System were used to develop the Drug-Exposed Infant Identification Algorithm (DEIIA). The DEIIA uses positive toxicology screens on the birth certificate and International Classification of Diseases, 9th Edition, Clinical Modification diagnostic codes in hospital records of the mother (prenatal and birth) and infant (birth and postnatal) to identify infants affected by substance abuse/dependence, withdrawal, and/or prenatal exposure to non-medical use of controlled substances. PELL-EI data linkages were used to determine the percent referred, evaluated, and eligible. The DEIIA identified 7,348 drug-exposed infants born in Massachusetts from 1998 to 2005 to resident mothers (1.2 % of all births). Most DEI (82.6 %) were identified from maternal/infant birth hospital records. Sixty-one percent of all DEI were referred to EI; 87.2 % of those referred were evaluated, and 89.4 % of those evaluated were found eligible. EI data contained information on drug exposure for 59.9 % of referred DEI. Only 2.8 % of MA resident births who were referred to EI but not identified by the DEIIA had drug indicators in EI data. DEI referrals to EI are federally mandated, but many are not referred. The DEIIA uses data available in most states and could be used as a public health screening tool to improve access to developmental services for DEI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Prenatal exposure to illegal drugs is a public health problem amenable to secondary prevention efforts through developmental services for newborns and their families. In 2004, federal legislation was passed [1] to improve Part C Early Intervention (EI) service access for drug-exposed infants (DEI) by requiring states to develop and implement EI referral policies and procedures for children under 3 years of age affected by illegal substance exposure. This mandate was motivated by scientific evidence of the detrimental effects of substance abuse and prenatal drug exposure on child development [2], yet data on the rate of EI service access among DEI are limited.

The 1997–1998 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (NHSDA) indicated that approximately 3 % of pregnant women reported using illicit drugs in the past month [3], while the 1998 National Early Intervention Longitudinal Study (NEILS) reported that approximately 2 % of children enrolled in EI in 1998 were receiving services because of prenatal exposures to substances (including alcohol) [4]. These data suggest that not all prenatally drug-exposed children were enrolled in EI services over 10 years ago, but do not precisely define the extent of problems with service access. More recent, population-based data on the number and percent of infants exposed to illegal drugs who are referred to EI would allow states to assess the scope of the problem and build appropriate service capacity.

Currently, there is no feasible population-based method to identify DEI for referral. The confidential NHSDA (now the National Survey on Drug Use and Health) responses may only be used for statistical purposes under federal law [5], and there are ethical and practical barriers to screening all pregnant women for drug use [6]. Australian researchers demonstrated the possibility of population level screening by linking birth records to prenatal and birth hospital admission data to identify prenatally drug exposed infants using hospital diagnostic codes [7]. Existing US-based methods that use hospital diagnostic codes focus on identifying adults with substance use disorders and are not designed to identify infants with prenatal exposure. For example, the mental health/substance abuse component of the Clinical Classifications Software (CCS-MHSA) [8] leaves out drug-related poisoning codes, and the Drug Need Index (DNI) [9] includes poisonings but leaves out pregnancy- and infant-related diagnoses indicating prenatal drug use. In summary, there is no gold standard method to identify DEI on a population basis.

This study addresses the need for a specific, feasible population-based tool to identify DEI. This paper describes the development and application of the Drug-Exposed Infant Identification Algorithm (DEIIA) to address three study questions: (1) how many infants born from 1998 to 2005 were identified as drug exposed and what were the time trends, (2) when, where, and by what indicators were infants identified; and (3) what percent of DEI were referred to and eligible for EI in Massachusetts?

Methods

Data Source and Sample

This study used data from the population-based Massachusetts Pregnancy to Early Life Longitudinal (PELL) Data System that links birth certificates, maternal and infant hospital records, and EI service records. The study population included 624,269 in-state livebirths to Massachusetts residents in maternity hospitals from 1998 to 2005 where the birth certificate linked to maternal and child birth hospitalization records (the “core” linkage). The DEIIA used PELL’s longitudinal linkages between the core [10], maternal prenatal and child postnatal hospital records [11], and EI participation records [12].

This study was approved by the Brandeis University and Massachusetts Department of Public Health Institutional Review Boards. Records were stripped of direct identifiers prior to analysis.

Drug-Exposed Infant Identification Algorithm

The DEIIA was developed to identify children under the age of three who are “… affected by illegal substance abuse, or withdrawal symptoms resulting from prenatal drug exposure” [§637(a)(6)(B)] [1] and as such, subject to the federal EI referral requirements. The algorithm defines the study population using indicators of three constructs: (1) abuse or dependence; (2) withdrawal; and (3) prenatal drug exposure. The three constructs were measured using two types of indicators: positive toxicology screens on the birth certificate (measuring prenatal drug exposure) and International Classification of Diseases, 9th Edition, Clinical Modification (ICD9-CM) drug-related diagnostic codes in maternal and infant hospital records (measuring any of the three constructs). Maternal records included delivery and prenatal hospital records (inpatient, emergency and observational stays); child records included birth and postnatal hospital records to age 3 years to capture prenatal exposures detected after birth [13].

The DEIIA was developed using an iterative five-step process. Step 1 evaluated how well the CCS-MHSA [8] and the DNI [9] could measure the constructs of interest, particularly illegal drug use. Records identified using these tools were examined, and specific codes and code combinations were evaluated through consultation with drug abuse researchers and clinicians. Although the DEIIA endeavors to identify illegal drug use, ICD9-CM substance-related codes vary in level of detail and legality cannot always be determined. Therefore, the DEIIA uses indicators of exposure to “non-medical use of controlled substances,” a term used by SAMHSA [14] to denote illicit drug use. Henceforth for brevity, “drug exposure” will be used to convey this concept.

Step 2 involved grouping ICD9-CM diagnostic codes into three broad categories, each with sub-categories with higher or lower face validity, and creating inclusion rules. The broad categories were specific, remission, and non-specific codes. Specific codes explicitly state abuse, dependence, or infant withdrawal; indicate prenatal exposure to drugs; and/or explicitly mention heroin, methadone, psychodysleptics/hallucinogens, or cocaine. Specific code sub-categories are positive toxicology screens, abuse, dependence-drug specified, noxious influences-drug specified (cocaine and hallucinogens), child withdrawal, and poisoning-specified illicit drug. Remission codes explicitly mention abuse or dependence to drugs included in the specific category, although the condition is in remission rather than continuous or episodic. Remission code sub-categories are abuse and dependence-drug specified. Non-specific codes may indicate non-medical use of controlled substances but are non-explicit. Non-specific code sub-categories were dependence-drug unspecified, seeking counseling, drug-induced disorder, noxious influences-drug unspecified (narcotics), maternal withdrawal, and poisoning-other drug.

Specific codes explicitly mention the three study constructs and therefore have higher theoretical face validity. Remission codes are considered to have higher face validity because they indicate a history of substance abuse, where relapse is common [15]. Non-specific codes have lower face validity because they lack detail. Code sub-categories were constructed based on face validity and the nature of the code (e.g., poisoning vs. dependence). Codes for drugs that are not considered drugs of abuse (e.g., antidepressant poisonings) and/or not considered illegal (e.g., antibiotics) were also identified to define a “do not include” category, and three additional categories were created for use in inclusion rules (suicide attempts, alcohol/tobacco, and anesthetic complications of labor and delivery).

Step 3 was a re-iteration of step 1, with the application of step 2 categories and rules. A factor analysis of sub-categories was conducted in step 4 to empirically determine how lower and higher validity codes clustered and examine whether cases identified only by the lower face validity codes should be included. Step 5 involved the application of the factor analysis results, theoretical considerations, and consultation with researchers and clinicians to refine the set of code indicators, categories, and inclusion rules.

Number of Drug-Exposed Infants and EI Referral and Eligibility

The total number of infants identified by the DEIIA is presented as a percentage of the total number of live births in Massachusetts between 1998 and 2005 captured in the PELL data system. An infant was considered referred to EI if s/he had a referral record linked to her/his birth record, and was considered eligible if the infant had a linked evaluation record with a date and eligibility information. The referral percent was calculated for DEI surviving past 28 days. The percent evaluated among those referred and the percent eligible among those evaluated were also calculated.

EI records can contain evidence of drug exposure, including (1) a drug-related referral reason (referral record); (2) an ICD9-CM diagnostic code related to drug exposure (292.0, 779.5, 977.9, and 989.9) (evaluation record); and (3) parental substance abuse (evaluation record). Referral and evaluation data were examined for all MA-born children referred to EI in MA, and the percent of referred children with evidence of substance exposure in EI records was calculated for both DEI (children identified by the DEIIA as drug-exposed) and non-DEI.

Statistical Methods

The Cochran-Armitage test for trend was used to examine time trends in birth of drug-exposed infants. Univariate statistics are presented for the following algorithm characteristics: when exposure was identified (prenatal, birth, postnatal, and multiple periods), where it was identified (e.g., birth certificate or maternal hospital discharge delivery record), and by what codes (types of drugs and higher vs. lower validity codes).

Sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the influence of key algorithm characteristics on referral, evaluation, eligibility, and EI substance exposure documentation percentages. These percentages were calculated using only children identified at birth (i.e., excluding prenatal- or postnatal-only identifications), children identified by high face validity indicators, and children identified at birth by high face validity indicators. All analyses were carried out using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Drug-Exposed Infant Identification Algorithm

The factor analysis identified 1 factor (Eigenvalue 2.01) with significant loadings >0.25 [16] for 3 high face validity sub-groups (abuse, dependence-drug specified and child withdrawal) and 2 low face validity sub-groups (dependence-drug unspecified and maternal withdrawal). Toxicology screen (high face validity) and noxious-drug unspecified (low face validity) also loaded weakly onto this factor (both 0.17). Noxious-drug specified (high face validity) and both poisoning sub-groups (high and low face validity) loaded more strongly onto a second, weak factor (Eigenvalue 0.33; loadings −0.19 and >0.30, respectively). Seeking counseling (V654.2) and drug-induced disorders had loadings of <0.10. Seeking counseling was dropped, and drug-induced disorder codes were dropped except for “suspected damage to fetus” codes (655.50, 655.51 and 655.53), which were retained based on theoretical grounds that prenatal exposure had been identified. Similarly, toxicology screens, poisoning and noxious influences codes were retained on theoretical grounds and after consultation with clinicians. Table 1 presents the final set of DEIIA indicators, categories and sub-categories, as well as the constructs they measure. The final inclusion rules and specific exceptions are presented in Table 2.

Number of Drug-Exposed Infants and EI Referral and Eligibility

A total of 7,348 children born from 1998 to 2005 were identified by the DEIIA as drug-exposed, representing 1.2 % of the study population. One percent of births were exposed in 1998, which increased to 1.6 % in 2005 (Cochran-Armitage test for trend Z = 13.3, p < 0.0001).

The majority were identified at birth (n = 6,195, 84.3 %) through hospital records (n = 6,071, 82.6 %). Almost 12 % (n = 870) were identified prenatally, but not at birth. There were 529 children identified with a postnatal drug exposure record, of which 283 (3.9 %) were identified postnatally only.

The sources that identified the highest percentage of infants were maternal hospital discharge delivery records and child hospital discharge birth records (73.0 and 44.4 %, respectively, non-mutually exclusive) (Table 3). Twelve percent were identified through birth certificates, of which 86.3 % had another exposure indicator in hospital records. Children’s postnatal inpatient, emergency, and observational stay records identified the lowest percentage of DEI (0.3–6.0 %). Almost half of the children (45.1 %) were identified in more than one data source.

Almost all infants were identified with higher validity indicators (n = 7,066, 96.2 %), and just 578 (7.9 %) infants were identified only by one of the code categories that did not cluster with the other categories. Among the 7,224 infants identified through hospital record indicators, most did not specify a drug (54.5 %), followed by codes specifying cocaine (38.7 %), opioids (35.1 %), and cannabis (26.3 %) (Table 3). Multiple drugs were indicated for 17.1 % of DEI, and 28.7 % also had indicators of alcohol and/or tobacco exposure.

Sixty-one percent of DEIIA identified surviving neonates were referred to EI before their third birthday (the service age cutoff) (Table 4). Once referred, 87.2 % received an evaluation, and 89.4 % of those children were eligible for EI. In sensitivity analyses, these percentages increased by ≤2.4 points.

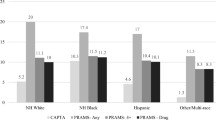

EI records indicated that the reason for referral was drug exposure for 40.6 % of referred DEI. A drug-related diagnosis was recorded in EI records for 6.8 % of evaluated DEI, despite the fact that 37.8 % of these infants had one of these diagnostic codes in their birth or postnatal hospital records. Parental substance abuse was recorded for 49.6 % of evaluated DEI. Overall, 59.9 % of referred DEI and 68.7 % of evaluated DEI had at least one of these drug exposure indicators in their EI records (Table 4). Just 2.8 % of referred non-DEI had a prenatal drug exposure indicator. Figure 1 presents the flow from the total population of births, to the DEI births, to referrals, to those with or without an EI record of prenatal drug exposure.

Discussion

This study used an innovative, population-based platform to develop the DEIIA, and provides novel data on the number of DEI in a state who received referrals to EI in accordance with the federal mandate. The DEIIA is a more specific and rigorous method to identify infants with prenatal drug exposure than is currently available. It identified as drug-exposed 1.2 % of Massachusetts births from 1998 to 2005, most at birth (84.3 %) through maternal delivery and infant birth hospital records (82.6 %) and high face validity indicators (96.2 %). Although the majority was referred to EI before age three, 39.1 % never received a referral. Once referred, most DEI received an eligibility evaluation (87.2 %) and were found eligible (89.4 %). EI records indicated prenatal drug exposure for 59.9 % of referred DEI, compared to only 2.8 % of referred children not identified by the DEIIA.

The DEIIA provides a feasible method of identifying prenatally drug exposed infants in need of EI that improves upon existing US-based diagnostic code algorithms. It is feasible because hospitals already collect the data and could use them to identify infants in need of referral. It improves upon existing methods because it was specifically designed to identify prenatal drug exposure rather than substance use disorders among adults, and unlike the CCS-MHSA, it underwent an empirical examination of construct measurement. The factor analysis findings that a few indicators did not cluster with the other indicators could be due to different data collection or measurement processes, a method effect, rather than to lack of overlap in construct measurement [17]. Toxicology screens come from a different source than the diagnostic codes; all poisonings are coded in a specific manner that differs from other diagnosis coding; and noxious influences codes cannot be used in the presence of a child withdrawal code [18]. Alternatively, the factor analysis results might be interpreted as indicating at least two different reasons for the prenatal drug exposure, which has practice implications and is an important avenue for further investigation.

The percentage of DEI identified in this study matches the 1.1 % figure reported in an Australian study using similar methods [7]. The DEIIA also indicated an increasing prevalence of DEI (1.0 % of 1998 births and 1.6 % of 2005 births), which corresponds to US national survey documentation of an increase in drug use by pregnant women from 2.5 % in 1997 to 1998 [3] to 3.9 % in 2005 [19]. The DEIIA detects only about 40 % of the births that might be expected based on these survey figures. It is likely capturing the most serious cases because identification required a hospitalization or detection by the hospital at delivery; not all women who use drugs during pregnancy are prenatally hospitalized, and drug use is often not detected at delivery [13]. The algorithm likely identifies those with higher levels of drug exposure who may have the most need of EI referral, which is supported by the high eligibility rates.

Policy and practice changes are needed to increase DEI access to EI and ascertainment of drug exposure in EI data. DEI referral and evaluation rates of 60.9 and 87.2 %, respectively, were much lower than rates reported by another Massachusetts study of 1998–2000 births. Referral and evaluation rates were 81.0 and 94.9 %, respectively, for infants born at <32 weeks gestation, and 89.0 and 95.7 %, respectively, for infants born weighing <1,200 g [12]. Among infants identified as drug-exposed by the DEIIA, 40.1 % of those who were referred and 40.6 % of those who were evaluated did not have information on drug exposure in their EI records. Although this could be used as a measure of sensitivity and specificity of the DEIIA in identifying DEI, EI data are not the gold standard for prenatal exposure identification. More appropriately, it documents the incompleteness of EI data with regard to conditions that impact eligibility and development. Drug exposure history may not be present if it was not a reason for referral or documented during the eligibility evaluation because EI is a voluntary system and parents do not have to share their history of drug use. This is indicated by the finding that only 6.8 % had a drug-related diagnostic code in their EI records, but 37.8 % had these same codes in their birth hospital record. Because drug exposure is a risk factor that contributes to eligibility in Massachusetts, some DEI might not have been found eligible when they should have been.

The DEIIA could be used by hospitals to screen their data and flag children for EI referral, and it could also be used as an objective indicator to prompt a toxicology screen at birth, both of which would likely increase referrals. Recording the hospital’s drug-exposure information at EI referral would improve the accuracy of the child’s medical history, which could help EI programs to identify eligible children and better serve these children and their families.

This study is subject to limitations inherent in using linked administrative data sources. Errors in hospital diagnosis coding could lead to under- or over-identification of DEI; it is not possible to determine if there is an overall bias in either direction. Although most infants were identified at birth, lower hospital longitudinal linkage rates may contribute to under-identification of DEI. Similarly, the linkages to EI referral data likely undercount DEI referrals. From 1998 to 2005 there were 1,946 referrals of children who were adopted (1,725) or did not have enough information for linkage. Assuming that 25 % of these children were DEI [20], the number of DEI referred would have been 4,923 (67.0 %), which nevertheless indicates that EI misses approximately one-third of DEI. Using evaluation dates and outcomes to measure evaluation and eligibility may also undercount the number of DEI who were evaluated and eligible. Although this is an approach that has been used in other studies of EI service access [12, 21], some children were missing evaluation data when the EI data system indicated they were evaluated and eligible.

The DEIIA uses toxicology screens on the birth certificate, but only two other states collect some type of prenatal drug use information on their birth certificates (based on 39 responses to an e-mail survey from 8/21 to 9/20/12 of vital records contacts in 56 US states and territories). Lack of standardization and inter-hospital variability regarding who completes the medical portion of the Massachusetts birth certificate using maternal/infant medical records/charts may contribute to variations in data quality, which has not been studied. Furthermore, toxicology screens are not universal. No studies have been identified that provide epidemiological data on the frequency with which screens are performed in any state, and Massachusetts is not one of the four states that require testing in response to suspicion of substance abuse [22]. Individual hospitals determine their testing protocols based on clinical factors (e.g., signs of substance use/abuse or withdrawal, placental abruption) and/or physician discretion [6]. Hospitals may not have a protocol [23], and sociodemographic bias has been reported even in the presence of protocols [24, 25]. Nevertheless, only 124 (1.7 %) of the children identified by the DEIIA were identified by a positive toxicology screen alone, and 86.3 % of the 905 children with a positive screen had another DEIIA indicator in infant/maternal hospital records.

In addition to potential under-identification of prenatal drug use, the DEIIA may also over-identify infants exposed to prescription drugs that the mother is taking under a physician’s guidance or who are otherwise not affected by illegal substance abuse, which is the group addressed by the federal referral mandate. The algorithm was designed so that it did not identify women with diagnoses that could easily be due to prescription drug use, and results did not change appreciably when excluding those who were identified by these lower validity indicators.

Additional validation studies are needed to strengthen the DEIIA as an epidemiological tool, but the DEIIA offers considerable public health utility as a population-based screening tool that provides a feasible method for states to monitor prenatal drug exposure and ensure children are getting needed services, as called for by experts [24, 26]. The finding that approximately 4 in 10 drug-exposed infants are not accessing potentially beneficial EI services in Massachusetts, a national leader in EI access [27], suggests a broader need to improve identification and referral of these infants. Further research is needed to understand access barriers and determine the outcomes of EI for DEI. EI and hospital policy and practice changes are needed to identify resources so that already strained state EI systems have the capacity to serve these additional children, and to carefully design and implement screening and referral protocols that are based on objective criteria and uniformly administered. The DEIIA is one tool that could be used to support and guide such efforts.

References

Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act. (2004). 20 U.S.C., Section 1400 et. seq., Pub. L. No. 108-446.

Shonkoff, J. P., & Phillips, D. A. (Eds.). (2000). From neurons to neighborhoods: The science of early childhood development. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2000). National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Main findings 1998. Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies, US Department of Health and Human Services.

Scarborough, A. A., Spiker, D., Mallik, S., et al. (2004). A national look at children and families entering early intervention. Exceptional Children, 70(4), 469–483.

Research Triangle Institute and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2012). National Survey on Drug Use and Health. https://nsduhweb.rti.org/. Accessed 15 Aug 2012.

National Abandoned Infants Assistance Resource Center. (2006). Substance exposed infants: Noteworthy policies & practices. Berkeley, CA: University of California, Berkeley.

Burns, L., Mattick, R. P., & Cooke, M. (2006). The use of record linkage to examine illicit drug use in pregnancy. Addiction, 101(6), 873–882.

HCUP CCS. (2011). Healthcare cost and utilization project. (HCUP). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available from: www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp.

McAuliffe, W. E., & Dunn, R. (2004). Substance abuse treatment needs and access in the USA: Interstate variations. Addiction, 99(8), 999–1014. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00783.x.

Declercq, E., Barger, M., Cabral, H., et al. (2007). Maternal outcomes associated with planned primary cesarean births compared with planned vaginal births. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 109(3), 669–677. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000255668.20639.40.

Weiss, J., Kotelchuck, M., Grosse, S. D., et al. (2009). Hospital use and associated costs of children aged zero-to-two years with craniofacial malformations in Massachusetts. Birth Defects Research, Part A: Clinical and Molecular Teratology, 85(11), 925–934. doi:10.1002/bdra.20635.

Clements, K. M., Barfield, W. D., Kotelchuck, M., et al. (2006). Birth characteristics associated with early intervention referral, evaluation for eligibility, and program eligibility in the first year of life. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 10(5), 433–441.

Young, N. K., Gardner, S., & Otero, C. et al. (2009). Substance-exposed infants: State responses to the problem. HHS Pub. No. (SMA) 09-4369. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2008). Results from the 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National findings. NSDUH Series H-34, DHHS Publication No. SMA 08-4343. Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies, US Department of Health and Human Services.

Stewart, J. (2000). Pathways to relapse: The neurobiology of drug-and stress-induced relapse to drug-taking. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, 25(2), 125–136.

Consulting Group of the Division of Statistics and Scientific Computing at the University of Texas at Austin. (1995). Factor analysis using Proc factor. In: Introduction to SAS. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Academic Technology Services Statistical Consulting Group. http://www.ats.ucla.edu/stat/sas/library/factor_ut.htm. Accessed 26 Dec 2011.

McAuliffe, W. E., Woodworth, R., Zhang, C. H., et al. (2002). Identifying substance abuse treatment gaps in substate areas. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 23(3), 199–208.

National Center for Health Statistics. (2011). International classification of diseases, Ninth Revision, clinical modification (ICD-9-CM). http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd9cm.htm. Accessed 6 Sep 2012.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2006). Results from the 2005 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National findings. NSDUH Series H-30, DHHS Publication No. SMA 06-4194. Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies, US Department of Health and Human Services.

Barth, R. P. (1991). Adoption of drug-exposed children. Children and Youth Services Review, 13(5–6), 323–342. doi:10.1016/0190-7409(91)90024-c.

Clements, K. M., Barfield, W. D., Kotelchuck, M., et al. (2008). Maternal socio-economic and race/ethnic characteristics associated with early intervention participation. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 12(6), 708–717.

Guttmacher Institute. (2012). Substance abuse during pregnancy. New York, NY: Author.

Mendez, D., Jacobson, P. D., Hassmiller, K. M., et al. (2003). The effect of legal and hospital policies on physician response to prenatal substance exposure. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 7(3), 187.

Ellsworth, M. A., Stevens, T. P., & D’Angio, C. T. (2010). Infant race affects application of clinical guidelines when screening for drugs of abuse in newborns. Pediatrics, 125(6), e1379–e1385. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-3525.

Veda Kunins, H., Bellin, E., Chazotte, C., et al. (2007). The effect of race on provider decisions to test for illicit drug use in the peripartum setting. Journal of Women’s Health (15409996), 16(2), 245–255. doi:10.1089/jwh.2006.0070.

Huestis, M. A., & Choo, R. E. (2002). Drug abuse’s smallest victims: In utero drug exposure. Forensic Science International, 128(1–2), 20–30.

Danaher, J., Goode, S., & Lazara, A. (2007). Part C updates (9th ed.). Chapel Hill, NC: The University of Carolina, FPG Child Development Institute, National Early Childhood Technical Assistance Center.

Acknowledgments

The author is indebted to Drs. William McAuliffe (Harvard University), Barry Zuckerman, Jason Wang, and Barbara (Bobbi) Philipp (all from Boston Medical Center), for their assistance in the design of the Drug Exposed Infant Identification Algorithm. Drs. Milton Kotelchuck (Massachusetts General Hospital/Harvard University) and Marji Erickson Warfield (Brandeis University) provided guidance on this project and comments on the study design and manuscript. Drs. Candice Belanoff (Boston University School of Public Health) and Dominic Hodgkin (Brandeis University) provided editorial assistance. Methodological guidance and instrumental assistance were provided by the following individuals: from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (MDPH), Ron Benham, Dr. Hafsatou Diop, Lynne Deschamps, Carol Davin, Patti Fougere, Dr. Susan Manning, Jean Shimer, and Michael Silver; from Boston University School of Public Health, Dr. Judith Weiss, Daksha Gopal, Qi Yu, Dr. Howard Cabral, and especially Manjusha Gokhale. This study was funded through a doctoral fellowship with the Lurie Institute on Disability Policy at Brandeis University, and through dissertation Grants from The Heller School for Social Policy and Management Alumni Association and the Office of the Provost, Brandeis University. The PELL Data System is a university-government partnership between the Boston University School of Public Health, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and was funded by the CDC (PELL Data System Expansion and Associated Analyses Contract No. 200-2009-31671).

Conflict of interest

The author has indicated no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose. The author reports no conflict of interest related to the design and conduct of the study or in the data analysis and manuscript preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Derrington, T.M. Development of the Drug-Exposed Infant Identification Algorithm (DEIIA) and Its Application to Measuring Part C Early Intervention Referral and Eligibility in Massachusetts, 1998–2005. Matern Child Health J 17, 1567–1575 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-012-1157-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-012-1157-x