Abstract

Prior studies of risk factors for depressive symptoms during pregnancy are sparse and the majority have focused on non-Hispanic white women. Hispanics are the largest minority group in the US and have the highest birth rates. We examined associations between pre and early pregnancy factors and depressive symptoms in early pregnancy among 921 participants in Proyecto Buena Salud, an ongoing cohort of pregnant Puerto Rican and Dominican women in Western Massachusetts. Depressive symptoms were assessed by the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (mean = 13 weeks gestation) by bilingual interviewers who also collected data on sociodemographic, acculturation, behavioral, and psychosocial factors. A total of 30% of participants were classified as having depressive symptoms (EPDS scores > 12) with mean + SD scores of 9.28 + 5.99. Higher levels of education (college/graduate school vs. <high school: RR = 0.60, 95% CI 0.41–0.86), household income (P trend = 0.02), and living with a spouse/partner (0.80; 95% CI 0.63–1.00) were independently associated with lower risk of depressive symptoms. There was the suggestion that failure to discontinue cigarette smoking with the onset of pregnancy (RR = 1.32; 95% CI 0.97–1.71) and English language preference (RR = 1.33; 95% CI 0.96–1.70) were associated with higher risk. Single marital status, second generation in the U.S., and higher levels of alcohol consumption were associated with higher risk of depressive symptoms in univariate analyses, but were attenuated after adjustment for other risk factors. Findings in the largest, fastest-growing ethnic minority group can inform intervention studies targeting Hispanic women at risk of depression in pregnancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Depression is one of the most common complications in pregnancy [1] and has been associated with adverse birth outcomes including preterm labor [2] and preterm birth [3, 4]. Prenatal depression is also an important predictor of postpartum depression [5] with one-third of women diagnosed with postpartum depression experiencing the onset of depression while pregnant [6]. Prenatal depression often remains unrecognized.

Rates of depressive symptoms during pregnancy vary widely with generally higher rates among women of low socioeconomic status and among racial/ethnic minorities [7]. Reported rates of depressive symptoms among Hispanic women have ranged from 16 [8] to 53% [9] depending on the screening instrument used, the cutpoint selected, trimester at the time of assessment, and the Hispanic subgroup studied. Among Latino subgroups, U.S. Puerto Ricans are at greater risk of postpartum depression [10] as compared to other Hispanic subgroups, and have more than double the rates of lifetime depression as compared to Mexican Americans and Cuban Americans [11].

These findings are critical as Hispanics are the largest minority group in the United States, with the highest birth and immigration rates of any minority group [12]. It is estimated that by 2050 Hispanic women will comprise 24% of the female population in the United States [13]. Hispanics from the Caribbean islands (i.e., Puerto Ricans and Dominicans) comprise the second largest group of Latinos living in the U.S. [12] and are the fastest growing subgroup.

In spite of this, the majority of studies of depressive symptoms during pregnancy have generally focused on non-Hispanic white women [14]. In these studies, risk factors for prenatal depressive symptoms included maternal anxiety, stress, history of depression, lack of social support, lower income, lower education, smoking, single status, teenage pregnancy, and first pregnancy, among other factors [14, 15]. These issues are common in the lives of many Puerto Rican women [11].

Increased acculturation of Hispanic women into the U.S. culture has been found to be positively related to drug and alcohol use in pregnancy [16], poorer perinatal outcomes, as well as mental health problems [17], factors which, in turn, are associated with increased risk of prenatal depression. However, the few studies of acculturation and depressive symptoms have been limited to the postpartum period [18, 19], or combined prenatal and postpartum women [20, 21], and observed inconsistent findings.

Therefore, we evaluated sociodemographic, acculturation, behavioral, and psychosocial predictors of depressive symptoms using baseline data from Proyecto Buena Salud, an ongoing prospective study of prenatal care patients of Puerto Rican and Dominican descent in Western Massachusetts.

Methods

Study Overview

Proyecto Buena Salud is based in the ambulatory obstetrical practices of Baystate Health in Western Massachusetts. Details of the study have been presented elsewhere [22]. Briefly, the overall goal of Proyecto Buena Salud is to examine the relationship between physical activity, psychosocial stress, and risk of gestational diabetes in Hispanic women of Caribbean Island heritage. Bilingual interviewers recruited patients at prenatal care visits early in pregnancy (up to 20 weeks gestation), informed them of the aims and procedures of the study and obtained written informed consent. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Massachusetts-Amherst and Baystate Health.

Eligibility was restricted to women of Puerto Rican or Dominican Republic heritage. Additional exclusion criteria included: current medications which adversely influence glucose tolerance, multiple gestation, history of diagnosis of diabetes, hypertension, heart disease or chronic renal disease, and <16 years of age or over 40 years of age. The majority of potential participants were ineligible either due to non-Puerto Rican/Dominican ethnic group (31%) or other exclusion criteria (i.e., <16 years, >20 weeks gestation, taking prednisone, or having twins/triplets) (65%), while 4% were excluded for preexisting disease [23].

Interviews were conducted in Spanish or English (based on patient preference) in order to eliminate potential language or literacy barriers. The baseline interview collected information on sociodemographic, acculturation, behavioral, and psychosocial factors.

Depressive Symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed by interviewers at baseline using the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) available in English [24] and Spanish [25]. Each item asks how the woman has felt during the previous week and includes four categorical response options (yes, most of the time, no, not at all).

Items are rated on a 4-point scale (0, 1, 2, 3) with a range of 0–30. Women with a score >12 were considered to have depressive symptoms, consistent with prior literature [8, 26]. The EPDS has been validated as a depression screening tool in pregnant and postpartum Hispanic women [27] and has a sensitivity of 90–100% and a specificity of 78–88% for the identification of major and minor depression [24].

Sociodemographic Factors

At the baseline interview, interviewers collected information on sociodemographic factors including age, education, annual household income, marital status, living situation (i.e., with a partner), and number of children and adults in the household.

Acculturation Factors

At baseline, interviewers queried language preference for speaking/reading (English, Spanish), birthplace (Puerto Rico/Dominican Republic, continental U.S.), as well as generation in the U.S. Interviewers also administered the Psychological Acculturation Scale (PAS) [28] which consists of ten items measuring an individual’s sense of psychological attachment to and belonging within Anglo-American and Latino/Hispanic cultures. Item responses are scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (only Hispanic/Latino) to 5 (only Anglo/American). We defined scores <3 as low acculturation and scores ≥3 as high acculturation. PAS scores have been correlated with migration history and patterns of Spanish and English language use in a sample of Puerto Rican females; correlations between PAS scores from the Spanish and English versions (r = 0.94) suggest a high degree of cross-language measurement equivalence [28].

Behavioral Factors

Behavioral factors were assessed at baseline using questions designed by the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), a surveillance project of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [29] and included pre- and early-pregnancy alcohol consumption and cigarette smoking.

Psychosocial Factors

Perceived stress was measured at baseline using Cohen’s Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-14) which includes 14 items designed to address a person’s sense of control over daily life demands [30]. The European Spanish version of the PSS-14 demonstrated adequate reliability (internal consistency, alpha = 0.81, and test-retest, r = 0.73), validity, and sensitivity [31]. Trait anxiety was assessed at baseline using the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) [32] which measures relatively stable individual differences in anxiety proneness and contains 20 statements about how the respondent generally feels. The instrument has been previously used in studies during the prenatal period [33]. The Spanish version of the STAI was validated and adapted by TEA Editions [34].

Data Analysis

We examined frequency distributions of sociodemographic, acculturation, behavioral, and psychosocial factors by EPDS scale score (≤12, >12) using chi square tests or Fisher’s Exact Test, in cases of small cell size. Multivariable logistic regression models included factors associated with depressive symptoms in the prior literature (i.e., age, education, income) [14] as well as acculturation, behavioral, and psychosocial factors which were statistically significantly associated with depressive symptoms in unadjusted logistic models at P < 0.20. When cohabitation status and marital status were both included in the model, marital status was no longer statistically significantly associated with depressive symptoms (P = 0.50), which led to the exclusion of marital status from the final model. We also excluded perceived stress and anxiety from the final model as these factors may reflect aspects of depression and were highly correlated with depressive symptoms (r = 0.66–0.81, P < 0.01). This is consistent with recent review articles which have found depression, stress, and anxiety to be highly comorbid during pregnancy [35].

Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for depressive symptoms in relation to potential predictors were calculated. Due to the non-rare outcome, ORs were corrected using the method of Zhang and Yu and transformed into relative risks [36]. Tests for linear trend were calculated by modeling the ordinal variables as continuous variables. Statistical analysis was conducted using SAS 9.2 software by SAS Institute Inc. (SAS Campus Drive, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

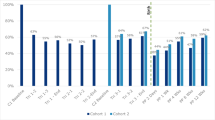

Recruitment into the study began in January 2006 and we present the results from participants recruited through December 2009 (n = 921). A total of 30% of participants were classified as having depressive symptoms (EPDS scores > 12) with mean + SD scores of 9.28 + 5.99. The participants were young (70% less than age 24), with low levels of education (49% had not graduated high school) and income (48% had an annual household income of <$30,000 per year) (Table 1). Although the vast majority of participants were never married (82%) nor living with a spouse/partner (48%), approximately 75% reported more than one adult in the household.

In terms of acculturation factors, 46% of women were born in Puerto Rico or the Dominican Republic and 80% reported, on average, being closer to a Latino cultural orientation (PAS score < 3) than to an Anglo-American cultural orientation (Table 1). Regarding behavioral factors, 32% of women reported pre-pregnancy alcohol consumption which decreased to 14% with the onset of pregnancy. Similarly, while 39% of women reported smoking cigarettes prior to pregnancy, 3% reported smoking in early pregnancy. In terms of psychosocial factors, the mean ± SD PSS score was 26.2 ± 7.1 and trait anxiety STAI score was 40.7 ± 10.3.

In bivariate analyses, increasing education and annual household income were inversely associated with depressive symptoms (Table 1). Women who were unmarried or did not live with a spouse/partner reported a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms. Women who preferred English or were second generation in the U.S. were more likely to report depressive symptoms compared to less acculturated women. Women who smoked cigarettes and consumed alcohol both prior to and during pregnancy had significantly higher rates of depressive symptoms compared to women who either did not use these substances, or discontinued them at the onset of pregnancy. Perceived stress and trait anxiety were both positively associated with depressive symptoms. Finally, age, number of children or adults in the household, birthplace, and score on the Psychological Acculturation Scale were not associated with report of depressive symptoms.

We developed a multivariable regression model which included predictors of prenatal depressive symptoms observed in the prior literature or found to be associated with prevalence of depressive symptoms in unadjusted analyses (Table 2). We excluded 87 participants from this model who had missing data on one or more of the predictors of interest for a final sample size of 834. In this multivariable model, women who had graduated high school (RR = 0.73, 95% CI 0.55–0.94) or had attended college/graduate school (RR = 0.60, 95% CI 0.41–0.86) had a lower risk of depressive symptoms compared to women with less than a high school education. Similarly, increasing income was significantly associated with lower risk of depressive symptoms (P trend = 0.02). Women who reported living with a spouse/partner had a lower risk of depressive symptoms as compared to women living alone (RR = 0.80; 95% CI 0.63–1.00).

There was the suggestion that women who preferred English had a higher risk of depressive symptoms as compared to women who preferred Spanish (RR = 1.33; 95% CI 0.96–1.70). Similarly, women who smoked both prior to and during pregnancy had the suggestion of an elevated risk of depressive symptoms (RR = 1.32; 95% CI 0.97–1.71) compared to women who did not smoke in either time period. Finally, single marital status, generation in the U.S., and alcohol consumption were attenuated and no longer statistically associated with depressive symptoms in multivariable models.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional analysis using baseline data from Proyecto Buena Salud, we found that almost one-third of Hispanic prenatal care patients reported prenatal depressive symptoms in early pregnancy. Higher levels of education and income, and living with a spouse/partner were independently associated with lower risk of depressive symptoms while there was the suggestion that failure to discontinue cigarette smoking with the onset of pregnancy and English language preference were associated with higher risk. While single marital status, second generation in the U.S., and higher levels of alcohol consumption were associated with higher risk of depressive symptoms in univariate analyses, these results were attenuated after adjustment for other risk factors. Finally, age, number of children and adults in the household, birthplace, and psychological acculturation score were not associated with depressive symptoms.

We observed a relatively high prevalence of prenatal depressive symptoms (30%) compared to prior studies among Hispanics as well as non-Hispanic white women [8]. Among studies using the EPDS to assess prenatal depression, Rich-Edwards et al. [8] found that Hispanic participants in Project Viva (5% of the sample) had a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms (EPDS scores > 12) in mid pregnancy compared with non-Hispanic white women (16% vs. 7%). In a prospective longitudinal study of women in England (n = 8,323), Evans et al. [26] found that 11.8% of women scored >12 on the EPDS at 18 weeks gestation. In their cohort of French women, Dayan et al. [37] found that 14.5% of participants scored >14 on the EPDS in mid pregnancy.

Prior studies focusing on Hispanic women were conducted predominantly among Mexican American women and used either the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) or the Beck Scale. Unlike the EPDS which is limited to cognitive and affective symptoms, the CES-D and Beck scales also query physical symptoms (e.g., fatigue and physical discomfort) which, because they are typical complaints of pregnancy, could lead to an overestimate of depression [8]. In these studies, the prevalence of depressive symptoms among Hispanic pregnant women ranged from 32.4 [7] to 51% (CES-D > 16) [20]. In addition, in a small sample of Puerto Rican women, Zayas et al. [9] found that 53% reported depressive symptoms in the third trimester (Beck scale > 14).

Aside from differences in population characteristics and screening tools, differences in findings may reflect demographic differences that are, in turn, related to depressive symptoms [8]. We found that increasing education, income, and living with a partner were associated with lower risk of depressive symptoms in multivariate analyses. Similarly, among a cohort of predominantly non-Hispanic white women, Rich-Edwards et al. found that women who were less educated, with fewer financial resources, and without a spouse/cohabitating partner had a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms in pregnancy. Similar findings have been observed among non-pregnant Hispanic women [21]. These findings have important public health implications as 48% of all births to Hispanics in the U.S. in 2005 were to women who were single [38].

The few studies of acculturation and depressive symptoms among Hispanics have been limited to the postpartum period [18, 19], or combined prenatal and postpartum periods [20, 21], and observed inconsistent findings. Authors have found either no difference in prevalence of depressive symptoms according to birth place [8, 18, 19] or acculturation [19], or a higher risk of depressive symptoms among Hispanics who were born in the U.S. [21], spent more years in the US [20, 39], or had higher acculturation scores [40]. Similarly, we found a suggestion that women who preferred English or who were second generation were more likely to report depressive symptoms compared to less acculturated women. In addition, participants reported a variety of characteristics which are potential risk factors for depression. For example, we observed higher levels of perceived stress and trait anxiety in this population compared to those reported by prior studies among predominantly non-Hispanic white populations [2, 41].

While we did not observe a statistically significant trend between age and depressive symptoms, we did observe a lower risk among women aged 16–24 as compared to women aged 25–29. However, the relative risks for the older age categories (30–40) were also consistent with a lower risk, although not significantly so. A recent systematic review on risk factors for depressive symptoms during pregnancy observed inconsistent findings for age [14]. Our finding may be confounded by social support, such that younger Hispanic women may be more likely to live with their extended family and have greater social support, as compared to older Hispanic women [42].

This study faces several limitations. The EPDS is a self-reported measure of depressive symptoms, as opposed to a clinical diagnosis. Although the EPDS has been validated among Hispanic pregnant women [27], minority women and women of low socioeconomic status may be particularly susceptible to social desirability bias [43]. While a score >12 on the EPDS does not confirm depression, the EPDS is widely used to indicate probable depressive disorder and factors associated with such scores have been predictive of clinically significant depression [27]. In addition, minority women of lower socioeconomic status might be less likely to receive a professional diagnosis or treatment for depression. Therefore the fact that our definition of depressive symptoms did not rely on treatment or diagnosis, could be considered a study strength. Finally, brief screening instruments have practical clinical utility in that they identify a high risk group who may benefit from intervention.

Another limitation of the study is its cross sectional design. Because we assessed both depressive symptoms and potential risk factors at the time of enrollment, we cannot ensure the temporality of the relationship, particularly for the lifestyle variables of smoking and alcohol consumption. However, for the socioeconomic variables (i.e., income, education, insurance) and acculturation factors (i.e., generation in US, language) we can be more assured that these factors preceded depressive symptoms during pregnancy. Our study did not collect information on other potential risk factors for depressive symptoms (e.g., unplanned pregnancy, history of depression, and social support) although, unlike some prior studies, we collected perceived stress and anxiety.

Marital status, generation in the U.S., and alcohol consumption were associated with higher risk of depressive symptoms in univariate analyses but were attenuated after adjustment for other variables. However, because many adverse life circumstances co-exist, these factors may be mediators or on the causal pathway for onset of depressive symptoms. For example, older generation in the U.S. may reflect higher acculturation which, in turn, was associated with higher alcohol consumption and smoking which, in turn, was associated with depressive symptoms in the final model. However, our goals were to identify correlates of prenatal depressive symptoms which could then be used to target women at risk who might benefit from intervention. In light of these goals, even results from the unadjusted analyses are important for targeting at-risk individuals and developing public health strategies.

Approximately 44% of women did not know their annual household income. This may have been due, in large part, to the young age of participants (70% less than age 24) and the fact that many lived at home with older family members, in unconventional living situations, and received public assistance. Women missing information on income did not differ significantly from women not missing this information in terms of their risk of depression. However, including these women in the multivariable regression models, while having the advantage of retaining a consistent sample size between unadjusted and adjusted analyses, had the potential limitation of including a category with a heterogeneous grouping of income. Finally, a total of 87 women were excluded from the final model due to missing information on one or more of the predictors of interest; however these women did not differ from those retained in the model with respect to risk of depressive symptoms (P = 0.61).

Because participants were recruited at prenatal care visits (up to 20 weeks gestation), we excluded, by definition, high-risk women who did not attend prenatal care. However, our study population included a sizeable proportion of women who were at high risk of depression based on socioeconomic factors and ethnicity. In addition, 2006 vital statistics data for births in Springfield, Massachusetts indicate that 93.3% of Hispanics begin prenatal care by the second trimester [44]. Because our population was limited to women of Puerto Rican or Dominican heritage, our findings cannot be generalized to other Hispanic subgroups. Finally, 4% of women were excluded for preexisting disease (e.g., type 2 diabetes). Risk factors for depression may differ among these women, and therefore findings cannot be generalized to this group.

The study also has several strengths. It addresses a gap in prior studies of depressive symptoms by focusing on Hispanics of Puerto Rican/Dominican origin during the perinatal period. As compared to prior studies, its sample size is relatively large with adequate numbers of both foreign-born and U.S.-born women. A further strength is its use of a standardized instrument, the EPDS, which has been the focus of extensive psychometric research and is not confounded by the physical symptoms of pregnancy. The study also documents the prevalence of depressive symptoms among a low-income, minority sample in Western Massachusetts.

In summary, Proyecto Buena Salud represents a group of Hispanic women with higher levels of depressive symptoms as compared to predominantly non-Hispanic white cohorts. Our findings support the potential role of routine screening for depression and for integrating psychosocial services into primary care practice. The impact of such intervention is likely to be greatest for Hispanics, given the high rates of fertility and births to single women among this population. Finally, because women are motivated to seek health care services during the prenatal period, embedding preventive interventions within obstetrical care settings can increase access to psychosocial services and improve the lives of both mothers and children.

References

Gaynes, B. N., Gavin, N., Meltzer-Brody, S., et al. (2005). Perinatal depression: Prevalence, screening accuracy, and screening outcomes. Evidence report/technology assessment; 1–8.

Dayan, J., Creveuil, C., Herlicoviez, M., et al. (2002). Role of anxiety and depression in the onset of spontaneous preterm labor. American Journal of Epidemiology [serial online], 155, 293–301.

Orr, S., James, S., & Prince, C. (2002). Maternal prenatal depressive symptoms and spontaneous preterm births among African-American women in Baltimore, Maryland. American Journal of Epidemiology, 156, 797–802.

Dole, N., Savitz, D. A., Hertz-Picciotto, I., Siega-Riz, A. M., McMahon, M. J., & Buekens, P. (2003). Maternal stress and preterm birth. American Journal of Epidemiology [serial online], 157, 14–24.

Robertson, E., Grace, S., Wallington, T., & Stewart, D. (2004). Antenatal risk factors for postpartum depression: A synthesis of recent literature. General Hospital Psychiatry, 26, 289–295.

O’Hara, M. W., Stuart, S., Gorman, L. L., & Wenzel, A. (2000). Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57, 1039–1045.

Lara, M., Le, H., Letechipia, G., & Hochhausen, L. (2009). Prenatal depression in Latinas in the U.S. and Mexico. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 13, 567–576.

Rich-Edwards, J. W., Kleinman, K., Abrams, A., et al. (2006). Sociodemographic predictors of antenatal and postpartum depressive symptoms among women in a medical group practice. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health [serial online], 60, 221–227.

Zayas, L. H., Jankowski, K. R. B., & McKee, M. D. (2003). Prenatal and postpartum depression among low-income Dominican and Puerto Rican women. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 25, 370–385.

Beck, C. T., Froman, R. D., & Bernal, H. (2005). Acculturation level and postpartum depression in Hispanic mothers. MCN American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing, 30, 299–304.

Potter, L. B., Rogler, L. H., & Moscicki, E. K. (1995). Depression among Puerto Ricans in New York City: The Hispanic health and nutrition examination survey. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 30, 185.

Zambrana, R. E., & Carter-Pokras, O. (2001). Health data issues for Hispanics: Implications for public health research. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved [serial online], 12, 20–34.

Misra, D. (2001). The women’s health data book (3rd ed.). Washington, DC: Jacob’s Women’s Health Institute.

Lancaster, C., Gold, K., Flynn, H., Yoo, H., Marcus, S., & Davis, M. (2010). Risk factors for depressive symptoms during pregnancy: A systematic review. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 202, 5–14.

Holzman, C., Eyster, J., Tiedje, L., Roman, L., Seagull, E., & Rahbar, M. (2006). A life course perspective on depressive symptoms in mid-pregnancy. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 10, 127–138.

Zambrana, R. E., Scrimshaw, S. C., Collins, N., & Dunkel-Schetter, C. (1997). Prenatal health behaviors and psychosocial risk factors in pregnant women of Mexican origin: The role of acculturation. American Journal of Public Health, 87, 1022–1026.

Acevedo, M. C. (2000). The role of acculturation in explaining ethnic differences in the prenatal health-risk behaviors, mental health, and parenting beliefs of Mexican American and European American at-risk women. Child Abuse Neglect, 24, 111–127.

Chaudron, L. H. (2005). Prevalence of maternal depressive symptoms in low-income Hispanic women. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry [serial online], 66, 418.

Kuo, W., Wilson, T., Holman, S., Fuentes-Afflick, E., O’Sullivan, M., & Minkoff, H. (2004). Depressive symptoms in the immediate postpartum period among Hispanic women in three U.S. cities. Journal of Immigrant Health, 6, 145–153.

Heilemann, M., Frutos, L., Lee, K., & Kury, F. (2004). Protective strength factors, resources, and risks in relation to depressive symptoms among childbearing women of Mexican descent. Health Care Women International, 25, 88–106.

Davila, M., McFall, S., & Cheng, D. (2009). Acculturation and depressive symptoms among pregnant and postpartum Latinas. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 13, 318–325.

Chasan-Taber, L., Fortner, R., Gollenberg, A., Buonnaccorsi, J., Dole, N., & Markenson, G. (2010). A prospective cohort study of modifiable risk factors for gestational diabetes among Hispanic women: Design and baseline characteristics. Journal of Women’s Health, 19, 117–124.

Chasan-Taber, L., Fortner, R. T., Hastings, V., & Markenson, G. (2009). Strategies for recruiting Hispanic women into a prospective cohort study of modifiable risk factors for gestational diabetes mellitus. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth, 9, 57.

Cox, J. L., Holden, J. M., & Sagovsky, R. (1987). Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. The British Journal of Psychiatry [serial online], 150, 782.

Jadresic, E., Araya, R., & Jara, C. (1995). Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) in Chilean postpartum women. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology [serial online], 16, 187–191.

Evans, J., Heron, J., Francomb, H., Oke, S., & Golding, J. (2001). Cohort study of depressed mood during pregnancy and after childbirth. BMJ, 323, 257–260.

Yonkers, K. A., Ramin, S. M., Rush, A. J., et al. (2001). Onset and persistence of postpartum depression in an inner-city maternal health clinic system. The American Journal of Psychiatry [serial online], 158, 1856–1863.

Tropp, L. R., Erkut, S., Coll, C. G., Alarcon, O., & Vazquez Garcia, H. A. (1999). Psychological acculturation: Development of a new measure for Puerto Ricans on the U.S. mainland. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 59, 351–367.

Williams, L. M., Morrow, B., Lansky, A., et al. (2003). Surveillance for selected maternal behaviors and experiences before, during, and after pregnancy. Pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system (PRAMS), 2000. MMWR Surveill Summ, 52, 1–14.

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 385–396.

Remor, E. (2006). Psychometric properties of a European Spanish version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS). The Spanish Journal of Psychology [serial online], 9, 86–93.

Spielberger, C. D. (1983). Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Hickey, C. A., Cliver, S. P., Goldenberg, R. L., McNeal, S. F., & Hoffman, H. J. (1995). Relationship of psychosocial status to low prenatal weight gain among nonobese black and white women delivering at term. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 86, 177–183.

Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L., & Lushene, R. E. (1986). Manual STAI. Cuestionario de Ansiedad Estado Rasgo. Adaptacion espanola.

Alder, J., Fink, N., Bitzer, J., Hsli, I., & Holzgreve, W. (2007). Depression and anxiety during pregnancy: A risk factor for obstetric, fetal and neonatal outcome? A critical review of the literature. Journal of Maternal—Fetal Neonatal Medicine, 20, 189–209.

Zhang, J., & Yu, K. F. (1998). What’s the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA, 280, 1690–1691.

Dayan, J., Creveuil, C., Marks, M. N., et al. (2006). Prenatal depression, prenatal anxiety, and spontaneous preterm birth: A prospective cohort study among women with early and regular care. Psychosomatic Medicine [serial online], 68, 938–946.

Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics. (2007). America’s children: Key national indicators of well-being.

Ruiz, R. J., Stowe, R., Goluszko, E., Clark, M., & Tan, A. (2007). The relationships among acculturation, body mass index, depression, and interleukin 1-receptor antagonist in Hispanic pregnant women. Ethnicity Disease, 17, 338–343.

Martinez-Schallmoser, L., Telleen, S., & MacMullen, N. (2003). The effect of social support and acculturation on postpartum depression in Mexican American women. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 14, 329–338.

Laraia, B. A., Siega-Riz, A. M., Gundersen, C., & Dole, N. (2006). Psychosocial factors and socioeconomic indicators are associated with household food insecurity among pregnant women. The Journal of Nutrition, 136, 177–182.

Wasserman, G. A., Rauh, V. A., Brunelli, S. A., Garcia-Castro, M., & Necos, B. (1990). Psychosocial attributes and life experiences of disadvantaged minority mothers: Age and ethnic variations. Child Development, 61, 566–580.

Bardwell, W. A., & Dimsdale, J. E. (2001). The impact of ethnicity and response bias on the self-report of negative affects. Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research, 6, 27–38.

Massachusetts Department of Public Health, Bureau of Health Information, Statistics, Research, and Evaluation, Division of Research and Epidemiology. Massachusetts Births 2006. Boston, MA: Massachusetts Department of Public Health, 2008.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH NIDDK064902.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fortner, R.T., Pekow, P., Dole, N. et al. Risk Factors for Prenatal Depressive Symptoms Among Hispanic Women. Matern Child Health J 15, 1287–1295 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-010-0673-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-010-0673-9