Abstract

Pregnancy weight gain may be a risk factor for the development of obesity highlighting the importance of identifying psychosocial risk factors for pregnancy weight gain. The goal of this qualitative pilot study was to evaluate knowledge, attitudes and beliefs regarding weight gain during pregnancy among predominantly Puerto Rican women, a group with higher rates of obesity as compared to non-Hispanic white women. We conducted four focus groups stratified by level of acculturation and BMI. Women reported receiving advice about pregnancy weight gain predominantly from nutritionists and family members rather than from their physicians. The majority of overweight/obese women reported that they had not received any recommendations for weight gain during pregnancy from physicians. Pregnancy weight gain advice was not consistent with the 1990 Institute of Medicine Guidelines. Overall, attitudes towards weight gain recommendations differed by weight status, whereas feelings and dietary beliefs about weight gain differed according to level of acculturation. Our findings inform behavior change strategies for meeting pregnancy weight gain recommendations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Pregnancy has been proposed as a critical period for the development of overweight and obesity both for the mother and the infant [1–6]. Excess weight gain during pregnancy has been associated with pregnancy complications, including cesarean delivery, large-for-gestational-age infants, and postpartum weight retention [7]. Compared to previous decades, American women of childbearing age currently enter pregnancy at a higher weight [8] and are more likely to gain excess weight during pregnancy [3, 9, 10]. Therefore, identifying modifiable risk factors that affect the development of obesity at early stages is critical. Psychosocial risk factors may play an important role in the development of excess weight gain during pregnancy, but research is limited [3, 11]. The 2007 Institute of Medicine report entitled “Influence of Pregnancy Weight on Maternal and Child Health” called for research to identify social predictors of weight gain during pregnancy [12].

Researchers who have examined psychosocial risk factors for failure to meet guidelines for weight gain in pregnancy have found that attitudes, beliefs, weight gain advice and social support are associated with risk of exceeding or not achieving recommended weight gain [13–18]. These studies have found that positive or negative attitudes may play a role in attaining either higher or lower weight gains during pregnancy and that these attitudes are influenced by pregravid body size [13, 19, 20]. Other studies suggest that past dieters and restrained eaters (those who consciously restrict food intake to control body weight or to promote weight loss) are less likely to experience weight gains within the recommended ranges during pregnancy [16, 21]. Studies have further shown that the amount of weight gained during pregnancy is influenced by healthcare provider recommendations, [14, 22] and have also reported that approximately 30–60% of women do not receive weight gain advice [3, 22, 23]. Pregnancy weight gain guidelines were based on the 1990 Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommendations which stated that weight gain should vary by pre-pregnancy weight for height as measured by body mass index (BMI) [24].

Although qualitative methods could be used to better understand these changes in weight gain, [25, 26] prior studies have been limited to quantitative assessments of predictors of pregnancy weight gain. Compiling qualitative data about the attitudes of participants is important for several reasons: first, pregnancy weight gain among women, particularly minority women, is likely to be influenced by personal, family, and community beliefs and attitudes about weight itself and its relationship to health and disease [27–29]. Quantitative studies may not fully capture these factors due to the close-ended nature of the assessment tools typically used in such studies. Second, beliefs about the health of the fetus and general pregnancy health may also influence women’s weight gain during pregnancy. Third, understanding beliefs about appropriate weight gain during pregnancy is crucial for intervention planning. Information about beliefs and practices from the perspective of potential program participants provides an essential foundation for the work of health educators and others responsible for pregnancy weight gain interventions. Finally, weight gain recommendations from health care providers may not be perceived as appropriate or feasible by low-income, urban-dwelling minority individuals or by their families and communities.

Qualitative studies of pregnancy weight gain are sparse and include little information about pregnancy weight gain-related attitudes, beliefs, practices or knowledge about current weight gain recommendations [27, 28, 30, 31]. One qualitative study among 46 Mexican adolescents found that those who had lost their traditional cultural beliefs related to pregnancy evidenced more negative attitudes about weight gain [28]. Using in-depth interviews in a second study of Mexican females, Thornton et al. [27] found that husbands and female relatives of women were primary sources of support for weight- and diet-related beliefs during pregnancy. Another qualitative study completed in the UK found that the ability to control weight gain during pregnancy varied, and that, in the absence of advice from health care professionals, women constructed their own views on how much weight it was appropriate to gain [31]. Lastly, a qualitative study of Cree women in Quebec found that although women spoke of the negative consequences of excessive weight gain during pregnancy, they found it difficult to lose weight postpartum due to constraints that included lack of time and cultural beliefs about diet [30]. Of these qualitative studies, none have included Hispanic women of predominantly Puerto Rican descent, one of the major Hispanic groups in the northeast United States [32].

Hispanic women are projected to have the highest birth rates of any minority group in the United States by the year 2009 [33]. According to a recent study of Puerto Rican women, approximately 22% of women gained below the IOM range, 33% gained within and 45% gained in excess [34]. According to this study, 19% of participants had been residing in the US for less than 10 years and found that time spent in the US was positively associated with the risk of gaining above the IOM range. Despite the high prevalence of obesity and excess weight gain during pregnancy in this ethnic group, [8, 35, 36] little is known about the modifiable risk factors for weight gain in this population.

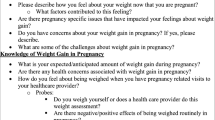

Our goal was to evaluate knowledge, attitudes and beliefs regarding weight gain during pregnancy in a predominantly Puerto Rican population using qualitative methods. Three areas were explored through a series of focus groups: (1) awareness of pregnancy weight gain guidelines; (2) feelings and attitudes about pregnancy weight gain, and (3) beliefs regarding the main contributors to weight gain during pregnancy.

Methods

Study Setting, Participants, and Recruitment

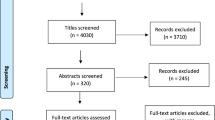

We conducted four focus groups with a total of 29 women at Baystate Medical Center, a large tertiary care facility in Western Massachusetts in January 2008. Baystate has the 25th largest obstetrical service in the United States and serves an ethnically and socio-economically diverse population with approximately 4,500 deliveries annually. Women were recruited in the waiting room before their prenatal care appointments by bilingual (Spanish and English)/bicultural interviewers who explained the study aims and administered a brief screening form to determine eligibility. Focus group participants met the following criteria: (1) aged 18–40 years, (2) singleton pregnancy, (3) at greater than 11 weeks and less than 28 weeks gestation, (4) self-identified as either Puerto Rican or Dominican, and (5) no diagnosis of chronic diseases (i.e., diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, chronic renal disease). The focus groups were stratified by level of acculturation using language preference as a proxy (i.e., English vs. Spanish preference) and by BMI (i.e., normal weight ≤25 kg/m2, overweight/obese >25 kg/m2). The final groups were comprised as follows: Spanish (low acculturated) normal weight (n = 5), Spanish (low acculturated) overweight/obese (n = 6), English (high acculturated) normal weight (n = 11) and English (high acculturated) overweight/obese (n = 7). The University of Massachusetts, Baystate Medical Center and Tufts University Institutional Review Boards approved all aspects of the study. Women were offered dinner, childcare and a $50 gift card for participating in the focus group.

Focus groups were moderated by a trained, bilingual Hispanic woman. Another member of the research team took notes, operated the digital recorder, and provided logistical support. The Spanish language preference groups were conducted in Spanish and the English language preference groups were conducted in English. Literature review [27, 29] and key informant interviews (n = 5) with community members, physicians, nutritionists and academics working with pregnant Hispanic women informed the content of the moderator guide used to lead the focus group discussions (see “Appendix”).

Open-ended questions were posed to stimulate discussions and included probes to address the different dimensions from the health belief model [37, 38]. All focus groups lasted approximately one hour and were audio-taped and transcribed verbatim. Spanish group transcripts were then translated. Based on the moderator guide questions (e.g., awareness of weight gain guidelines), key phrases were coded from the transcripts. During this initial coding process, additional themes emerged from the data and were added to the existing themes [39, 40]. Once the first pass of the coding was complete, the authors convened to discuss the major themes and build consensus. Subsequently, a second pass of the transcripts was completed in order to ensure that all of the a priori and emergent themes were captured. Identification of concepts and themes in the transcribed narratives was accomplished using NVIVO8 software (QSR International Pty Ltd.)

Results

The focus group participants all self-identified as Puerto Rican or Dominican. The women ranged in age from 18 to 40 years, and were between 11 and 28 weeks gestation. The major concepts generated from the focus groups and their corresponding response themes are presented in Table 1.

Concept 1: Awareness of Weight Gain Guidelines

Response Theme: Advice from Health Professionals

Women across all four groups (high acculturated normal and overweight/obese and low acculturated normal and overweight/obese) mentioned receiving weight gain advice from either a WIC (Women, Infants, and Children program) nutritionist or from a nutritionist at the hospital where they received prenatal care. Women discussed receiving advice from their physician less often, however, with high acculturated women in the overweight/obese group being the least likely to receive advice from physicians and nutritionists. In all of the groups, responses with regard to the type of weight gain advice received from health professionals varied considerably (Table 2). For example, participants in the low acculturated normal weight group commented:

WIC told me that it isn’t good to lose weight.

The nutritionist from the hospital says to limit weight gain and to limit soda.

A woman from the high acculturated obese/overweight group commented:

They give you advice and I don’t know if it is a lot of factors that go into it-maybe it’s because when you gain less weight it will make your birth easier.

I don’t know what it (weight gain advice) is, but they do stress it a lot though…I don’t hear it from my doctor, but I do hear it from the nutritionist.

Finally, women often commented that what they knew with respect to weight gain derived from their personal weight gain experience (i.e., gaining too much weight in a prior pregnancy). For example:

The nutritionist gave me advice about weight gain because when I had my first baby I gained too much weight.

Response Theme: Advice from Family Members

Family members played an important role in providing advice about weight gain during pregnancy in all of the groups, with less acculturated women reporting the most advice from family members and high acculturated overweight/obese group reporting the least (Table 2). The family members most frequently mentioned were mothers, mothers-in-law, as well as aunts, husbands and boyfriends. While the specific advice varied, the major theme that emerged was that pregnant women “should be eating for two.” Family advice differed from the advice received from nutritionists in that they did not tell them that they should be eating for two. Family advice in all of the groups suggested that family members were supportive of weight gain during pregnancy, since the excess weight would be “feeding the baby” and the babies, therefore, would be healthier. A woman from the low acculturated group commented:

My family says that you have to eat and eat…because you are eating for two.

A woman from the high acculturated overweight/obese group commented:

When you are pregnant I think family pushes you more; they think the fatter you get, the healthier the baby is.

Response Theme: Knowledge About Weight Gain Recommendations

Women were asked about weight gain recommendations and if they knew, specifically, how much weight they were supposed to gain during their pregnancy. Knowledge about weight gain recommendations varied greatly, both by group and within groups (Table 2). The normal weight groups reported more knowledge about weight gain recommendations as compared to the overweight/obese groups, although the estimate of the actual amount they were supposed to gain varied. Knowledge about weight gain recommendations did not differ by level of acculturation. A woman from the high acculturated normal weight group commented:

They say it depends on how much you weigh already, because if you are already overweight you don’t want to gain 35 pounds more because you will have diabetes and all that stuff.

In contrast, the overweight and obese groups often mentioned that they had not received weight gain recommendations. Those who recalled hearing a recommendation reported levels that were higher than the 1990 IOM weight gain guidelines [24]. For example, a woman from the high acculturated overweight/obese group commented:

Something like 5 pounds a month or something like that, I forgot, they say like 35 pounds that you can gain?

Response Theme: Attitudes About Weight Gain Recommendations

The majority of women did not consider weight gain recommendations to be important (Table 2). Several women in each of the groups thought that recommendations should be more personalized given that not all women have the same lifestyle or body size, for example:

Each person’s lifestyle is different- I would like to be in bed all day but I work and on the weekends I go to school from 9-5 so I don’t have a life. And sometimes I don’t even have time to eat! If they tell me that I have to gain a certain amount or if they tell me that I have to lose more, well I don’t know how I would do it. It depends on each person, each person needs something different.

It’s like they can’t tell you how much to gain, how much to lose- it is on your body and it’s hard- it’s like putting you on a diet- nobody follows a diet, you got to be 100% committed and if you are not 100% committed it is not going to work for you.

The high acculturated overweight/obese group mentioned the challenges of trying to stay within recommendations:

I think it is impossible to stay within weight guidelines because you just want to eat.

I told my doctor that I couldn’t worry about my weight, cause 10 pounds is the baby, so me gaining only like 12 pounds- that is impossible!

Other differences between groups with regards to attitudes about weight gain were not apparent.

Response Theme: Barriers to Staying Within Recommendations

Barriers to compliance with weight gain recommendations did not differ by group (Table 2). The most common barriers cited were work, time, pressure from family members to eat, morning sickness, stress, and hunger. Overall, women articulated that having a healthy baby and a healthy pregnancy were priorities to them, but that having a healthy baby was not related to pregnancy weight gain or complying with weight gain recommendations.

I just think it is necessary to gain, you know, you want to be healthy and you want your baby to be healthy so as long as you don’t go 100 pounds, gaining 100 pounds…and like if you put your mind to it, you can get rid of it after the baby is born. It’s up to you if you want to sit on the couch with the baby and get bigger or have the baby and go healthier …

Another barrier which emerged was how morning sickness interfered with daily life, especially at the beginning of pregnancy. Women felt that weight gain could not be a priority in the presence of morning sickness.

It should be important, but not only do we not have time but also when you are vomiting and that- you can’t really do anything for that- and I am still dealing with that.

Concept 2: Feelings and Attitudes About Pregnancy Weight Gain

Response Theme: Negative Feelings About Weight Gain

Overall, women reported negative feelings regarding weight gain during pregnancy. These feelings were shared across all of the groups, although to a lesser extent in the high acculturated overweight/obese group. Some of the most frequently mentioned feelings were: frustration, self-consciousness, feeling fat, and feeling sensitive. The less acculturated women felt that they would often get comments about their appearance from their family members and friends. Comments from the low acculturated groups included:

Sometimes I get frustrated because I am from Puerto Rico and when they see me they say, ‘but you are so fat’

Well, with respect to weight gain, well, where I was brought up, it is a competition- it is something about Hispanics- that I want to look good- and that if you gain a little bit of weight, they will see you and say something bad and that is something from our culture.

It comes from family, for example I have my family and we are several women and my aunts and grandmothers are always noticing how you look, if you are fat or thin, this and the other…how does that person look?

High acculturated women also expressed negative feelings about weight gain during pregnancy, though the specific feelings differed slightly:

I am gaining a lot of weight and I don’t like it. I am scared- I am fat and huge!

I just wish everything were fitting me and I could go back to my regular size.

Not happy, not happy at all because it is hard to lose it after the birth.

Other feelings about gaining weight during pregnancy did not differ by weight status.

There were also cultural differences that differed by level of acculturation. The low acculturated women who had lived in Puerto Rico or had visited Puerto Rico recently thought that there were some clear differences with respect to being pregnant. These differences were that they may have received different medical treatment in Puerto Rico vs. the mainland. For example:

I always ask the doctor here where I am, how far along I am …and they don’t tell me anything exact, I am completely lost. I wanted to prepare, I want a natural birth and the doctor here tells me to decide, what does he mean I should decide? He should tell me what to do….yes I am definitely lost and here when I go to have a check up and they check your papers and they ask you if you have any pain and I am like….tell me about the baby? How is the baby? I haven’t seen my baby in all this time, just once.

Other differences they reported were with regards to feeling like their physical appearance was more important in Puerto Rico than on the mainland.

In Puerto Rico, you can’t go out because they criticize you.

When I went to Puerto Rico and I looked at the other girls, I felt bad- because I am ‘gordita’ or chubby.

Concept 3: Beliefs Regarding the Main Contributors to Pregnancy Weight Gain

Response Theme: Diet

Throughout the focus groups, diet and nutrition were frequently mentioned. Women identified eating larger amounts of food than usual and doing it in an unhealthy manner as the major contributors to pregnancy weight gain. The main aspects of a “healthy diet” mentioned related to portion sizes and snacking throughout the day. Consumption of fruits and vegetables was not discussed as part of a healthy diet. Although all four groups were knowledgeable to some extent with regard to what constitutes a “healthy diet” (such as paying attention to portion sizes) many reported wanting to eat a lot of food. For example:

I do eat because I am hungry- you can’t stop eating!

All I do is eat and eat…

I don’t eat breakfast – but afterwards I eat the entire fridge and whatever else is left around.

The less acculturated women were more likely to mention their traditional foods in contrast to women who were more acculturated. Some of this discussion was around different traditional foods and their delicious taste. For example:

I like gizzards with plantains stewed (‘sancochado’.)

The Boricuas (Puerto Ricans) eat a lot of marinated or stewed things.

These women also pointed out that the dietary recommendations may differ between Puerto Rico and the mainland:

With the food, it is really different in Puerto Rico, when you go to the doctor they say one thing and then you come here and they say something different.

It depends as well on the doctor because when I had a baby in Puerto Rico, they made me eat fish and healthy things but here they don’t want you to eat fish.

Many women mentioned that morning sickness, especially towards the beginning of the pregnancy, was problematic for eating in general. Women also frequently said that they felt fuller faster when they ate, but sometimes continued to eat, and then felt sick. Women across all groups said they lost weight at the beginning of pregnancy and that they really could not eat a variety of foods:

At the beginning, I didn’t eat anything, I could go through a whole day without eating, but now I can’t- now I eat till you feel like you are going to die.

For four months since October that I am pregnant, I have vomited all of the time and you sometime throw up all that you eat and sometimes at 4:00 in the morning you have to be in the bathroom – and that doesn’t let you gain weight.

Women also frequently mentioned wanting to eat “junk food.” They did not call this a craving per se, but it appeared to be part of their day-to-day diet.

I wanted burritos, beans and cheese- nothing more.

At the beginning it was the potatoes, I also wanted the double cheese and after it was nachos and Taco Bell and pizza.

I was dying for some Taco Bell like for four days straight.

To most women, maintaining a healthy diet was difficult for several reasons, including their feelings that eating healthy was challenging due to their busy lives and that eating at a fast food restaurant was easier. This sentiment was voiced in all of the groups.

Besides, the healthy food you have to prepare it, to cook the food. The easiest thing is to go to a Burger King or McDonalds…and the healthy option is to cook but you already have enough to do – cooking is hard.

Response Theme: Physical Activity

Physical activity was not frequently discussed with regards to weight gain. Some women, however, did mention exercise as a means to lose weight after pregnancy. Most women felt that walking was the best and safest way to exercise and many women also felt that they did not have time to exercise due to childcare and household responsibilities. These comments did not differ by group.

They say walking is good to do it a lot….no lifting and things like that- just walking.

It is really hard because you are on the street the whole day and you try to walk but you have too many things.

Theme: Family

Families were discussed in the context of their contribution to weight gain during pregnancy. This was especially true in the low acculturated groups, where many women felt that their families would overfeed them or that they had to eat the foods that they were given. This aspect of family influence did not differ by weight status.

My family lives far away, every time that they come here they make me a huge pot of beans and beef and they make the whole pot just for me….and whoever tries to take food from that pot- they better be careful!

My family just suffocates me. Because with food, I would often throw up a lot, I was trying not to eat too much and they (my family) kept trying to feed me and I kept telling them that I didn’t want it and they make you feel bad so I would go to sleep and then he (husband) would come over and tell me to wake up so I could eat something …that was just too much!

Other times families merely influence food choices:

I can’t see McDonald’s and what my husband and my entire family likes is McDonald’s, my mother, my grandmother and my daughter and now…I think I already ate everything I had to eat at McDonald’s.

Discussion

The goal of this qualitative pilot study was to evaluate knowledge, attitudes and beliefs regarding weight gain during pregnancy in Hispanic women. We found that this sample of predominantly Puerto Rican women report receiving advice about pregnancy weight gain largely from nutritionists and family members rather than from physicians. This differed by level of acculturation, with low acculturated women receiving more advice from family members than the high acculturated groups. In all of the groups, however, family members supported weight gain based on the belief that this would lead to a healthier baby. The majority of women in the overweight/obese groups reported not receiving any recommendations for weight gain during pregnancy from physicians. The pregnancy weight gain advice that was received varied widely and was not consistent with the 1990 IOM guidelines [24]. According to this sample of women, the main contributors to weight gain during pregnancy were diet and family as well as weight gain in a prior pregnancy. In general, women did not consider standard weight gain recommendations to be important and thought they should be individualized. Overall, weight gain advice, knowledge about weight gain recommendations and attitudes towards weight gain recommendations differed by weight status, whereas weight gain advice, dietary beliefs and feelings about weight gain differed according to acculturation status. In contrast, barriers to staying within weight gain recommendations and beliefs about physical activity during pregnancy did not differ by weight or acculturation status.

There have been few studies of weight gain advice during pregnancy [14, 22, 23]. One of these studies among pregnant Canadian women found that women who gained excessive amounts of weight were less likely to have spoken with a physician about weight gain and were more likely to have had a higher prepregnancy BMI [41]. Our findings that overweight and obese women in particular reported not receiving advice about weight gain during pregnancy are consistent with these findings. This may be due, in part, to the failure of the 1990 IOM recommendations to provide an upper weight gain limit for this group of women. We also found that overweight and obese women thought that gaining only a small amount of weight during pregnancy was not realistic. Inasmuch as obese pregnant women appear to have better pregnancy outcomes with weight gains of less than the 1990 recommended IOM guidelines, [42] assessing obese women’s attitudes about these guidelines is crucial. Prior studies have reported that approximately 30–60% of women do not receive weight gain advice, but these studies have not reported on the accuracy of such advice among those who did receive it [3, 22, 23]. For example, we found that normal weight women reported receiving advice from health professionals, particularly nutritionists, but that the content of such advice was inconsistent.

We also found that less acculturated women were more likely to receive advice about weight gain from family members and that such advice focused on eating enough for two. A study of Mexican pregnant women showed that women were primarily influenced by their husbands and to lesser degree by their mothers-in-law and the media on issues concerning weight [27]. Our findings were similar, however, media was not mentioned as a source of weight gain guidelines. Familialism, a cultural value emphasizing close family relationships, has been used to describe Hispanic families [43]. Our finding that less acculturated women received advice about weight gain from their families is consistent with the concept of familialism. Several of the women seemed ambivalent towards the influence of their family, however, given that their advice sometimes went against their own resolve or wishes.

The majority of women in all of the groups felt negatively about gaining weight. Prior studies among predominantly non-Hispanic white pregnant women have shown that women with negative attitudes toward weight gain are more likely to exceed weight gain guidelines because pregnancy results in disinhibition of eating [16, 21]. Another study among predominantly non-Hispanic whites found that women who gained excess weight felt more unattractive, embarrassed about their weight, and worried they would get fat as compared to those who gained within recommendations [44]. In contrast, other studies have found that maternal attitudes regarding weight gain are strongly influenced by prepregnancy body size, with thin women having more positive attitudes and obese women having more negative attitudes about weight gain [19, 45]. These feelings were not expressed in our focus groups, which may be due to differences in the race/ethnicity of our groups. Although the majority of women felt negatively about gaining weight, they still felt that being attractive meant having a fuller body and wider hips. In particular, women in the less acculturated groups felt more social pressure from their families, friends and community to “look good.”

Diet was frequently mentioned as an important influence on pregnancy weight gain among focus group participants. Overall, women in our sample had some nutrition knowledge, especially with regard to portion sizes; however other aspects of healthy eating were not discussed. Previous studies have not assessed women’s opinion of the extent to which diet influences weight gain. It is interesting to note that for this group of Hispanic women, the traditional diet was a part of the daily diet, especially among the less acculturated groups. Adopting a more traditional Hispanic diet may result in healthier eating patterns [46]. Also noteworthy, lack of physical activity was not mentioned as a major contributor to weight gain. In a prior study of Puerto Rican women, we found that lack of information on physical activity during pregnancy was a barrier to exercise during pregnancy (manuscript under review).

Several limitations of this study should be noted. Although we conducted four focus groups, we were limited to one focus group within each strata of weight and acculturation, similar to other qualitative studies. Nonetheless, even with this number of groups, we were able to identify psychosocial risk factors for pregnancy weight gain, as well as commonalities and differences between groups according to acculturation and weight status. Second, we did not have information on gestational weight gain and therefore could not assess the influence that women’s knowledge, attitudes and beliefs had on meeting weight gain recommendations during pregnancy. In addition, we could not confirm what women were actually being told by healthcare providers; it is possible that women’s recall of weight gain recommendations is unreliable. Third, Hispanic women in the current study were, by design, limited to those with ancestral roots in Puerto Rico or the Dominican Republic, reflecting the high percentage of these groups in New England. The generalizability of these results to other Hispanic women (e.g., Mexican, Central American) is thus unknown. Fourth, we did not collect information on whether the participants were from Puerto Rico or from the Dominican Republic and differences in views on pregnancy weight gain may differ between these groups. Prior research completed with this Hispanic population at the same medical center as the current study found that approximately 90% of the participants were of Puerto Rican descent [47].

Implications for Research and Practice

Hispanic women enter pregnancy at higher weights and are projected to have the highest birthrates of any minority group in the United States by the year 2009 [33]. Given that nearly half gain in excess of the IOM range and that time spent in the US has been positively associated with the risk of gaining above this range [34], addressing modifiable risk factors for excess pregnancy weight gain in this ethnic group is important. In this qualitative pilot study we found that Hispanic women of predominantly Puerto Rican descent were aware of the importance of weight gain during pregnancy, but were lacking clear guidance from healthcare professionals. If future research studies confirm these preliminary findings, several policy implications follow. These include improved training of healthcare providers in the provision and consistency of weight gain recommendations to diverse population groups. Healthcare providers should emphasize the importance of these guidelines for womens’ health and work with them to achieve a realistic weight gain for pregnancy. In addition, setting guidelines as to which healthcare provider (physician vs. nutritionist) should be sharing weight gain recommendations is important. Because family plays a key role in changing health behaviors among Hispanic women, [29, 48, 49] particularly among less acculturated Hispanic women, education of family members on weight gain recommendations and guidelines on how to get involved would also be crucial to the success of such programs. Prior studies which have evaluated the role of social support in Hispanic communities have found that family plays a key role in changing health behaviors [29, 48, 49].

Ensuring that healthcare professionals receive appropriate cultural competency training to develop awareness of Hispanic cultural differences with respect to pregnancy weight gain beliefs is also essential. Intervention studies have shown that including nutrition counseling or an educational component may be beneficial to achieving appropriate weight gain during pregnancy [50]. Our findings support the need for improved communication around weight gain recommendations and informed behavior change strategies for meeting such recommendations during prenatal care. Future work should be designed to confirm the findings from this pilot study, and use them to design appropriate interventions for healthy pregnancy weight gain.

References

Siega-Riz, A. M., Evenson, K. R., & Dole, N. (2004). Pregnancy-related weight gain—a link to obesity? Nutrition Reviews, 62, S105–S111.

Ohlin, A., & Rossner, S. (1990). Maternal body weight development after pregnancy. International Journal of Obesity, 14, 159–173.

Olson, C. M., & Strawderman, M. S. (2003). Modifiable behavioral factors in a biopsychosocial model predict inadequate and excessive gestational weight gain. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 103, 48–54.

Gunderson, E. P., & Abrams, B. (2000). Epidemiology of gestational weight gain and body weight changes after pregnancy. Epidemiologic Reviews, 22, 261–274.

Oken, E., Taveras, E. M., Kleinman, K. P., Rich-Edwards, J. W., & Gillman, M. W. (2007). Gestational weight gain and child adiposity at age 3 years. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 196(322), e1–e8.

Moreira, P., Padez, C., Mourao-Carvalhal, I., & Rosado, V. (2007). Maternal weight gain during pregnancy and overweight in Portuguese children. International Journal of Obesity (London), 31, 608–614.

Viswanathan, M., Siega-Riz, A. M., Moos, M. K., Deierlein, A., Mumford, S., Knaack, J., Thieda, P., Lux, L. J., & Lohr, K. N. (2008). Outcomes of maternal weight gain. Evidence Report Technology Assessment (Full Rep), 1–223.

Hedley, A. A., Ogden, C. L., Johnson, C. L., Carroll, M. D., Curtin, L. R., & Flegal, K. M. (2004). Prevalence of overweight and obesity among US children, adolescents, and adults, 1999–2002. JAMA, 291, 2847–2850.

Schieve, L. A., Cogswell, M. E., & Scanlon, K. S. (1998). Trends in pregnancy weight gain within and outside ranges recommended by the Institute of Medicine in a WIC population. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 2, 111–116.

Helms, E., Coulson, C. C., & Galvin, S. L. (2006). Trends in weight gain during pregnancy: a population study across 16 years in North Carolina. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 194, e32–e34.

Olson, C. M. (2008). Achieving a healthy weight gain during pregnancy. Annual Review of Nutrition, 28, 411–423.

Institute of Medicine. (2007). Influence of pregnancy weight on maternal and child health: A workshop report. Washington, DC: National Research Council Institute of Medicine, pp. 1–93.

Palmer, J. L., Jennings, G. E., & Massey, L. (1985). Development of an assessment form: attitude toward weight gain during pregnancy. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 85, 946–949.

Taffel, S. M., & Keppel, K. G. (1986). Advice about weight gain during pregnancy and actual weight gain. American Journal of Public Health, 76, 1396–1399.

Fairburn, C. G., Stein, A., & Jones, R. (1992). Eating habits and eating disorders during pregnancy. Psychosomatic Medicine, 54, 665–672.

Conway, R., Reddy, S., & Davies, J. (1999). Dietary restraint and weight gain during pregnancy. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 53, 849–853.

Hickey, C. A., Cliver, S. P., McNeal, S. F., Hoffman, H. J., & Goldenberg, R. L. (1996). Prenatal weight gain patterns and birth weight among nonobese black and white women. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 88, 490–496.

Hurley, K. M., Caulfield, L. E., Sacco, L. M., Costigan, K. A., & Dipietro, J. A. (2005). Psychosocial influences in dietary patterns during pregnancy. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 105, 963–966.

Copper, R. L., DuBard, M. B., Goldenberg, R. L., & Oweis, A. I. (1995). The relationship of maternal attitude toward weight gain to weight gain during pregnancy and low birth weight. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 85, 590–595.

Stevens-Simon, C., Nakashima, I., & Andrews, D. (1993). Weight gain attitudes among pregnant adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 14, 369–372.

Fairburn, C. G., & Welch, S. L. (1990). The impact of pregnancy on eating habits and attitudes to shape and weight. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 9, 153–160.

Stotland, N. E., Haas, J. S., Brawarsky, P., Jackson, R. A., Fuentes-Afflick, E., & Escobar, G. J. (2005). Body mass index, provider advice, and target gestational weight gain. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 105, 633–638.

Cogswell, M. E., Scanlon, K. S., Fein, S. B., & Schieve, L. A. (1999). Medically advised, mother’s personal target, and actual weight gain during pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 94, 616–622.

Institute of Medicine. (1990). Weight gain: Nutrition during pregnancy. Part 1. Washington, DC.

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods: Qualitative research (c 3/ed) and evaluation methods. Beverley Hills, CA: Sage Publications Inc.

Berg, B. L. (2007). Qualitative research methods for the social sciences, ed. S. Edition. Boston: Pearson Education Inc.

Thornton, P. L., Kieffer, E. C., Salabarria-Pena, Y., Odoms-Young, A., Willis, S. K., Kim, H., et al. (2006). Weight, diet, and physical activity-related beliefs and practices among pregnant and postpartum Latino women: the role of social support. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 10, 95–104.

Gutierrez, Y. M. (1999). Cultural factors affecting diet and pregnancy outcome of Mexican–American adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 25, 227–237.

Kieffer, E. C., Willis, S. K., Arellano, N., & Guzman, R. (2002). Perspectives of pregnant and postpartum latino women on diabetes, physical activity, and health. Health Education and Behaviour, 29, 542–556.

Vallianatos, H., Brennand, E. A., Raine, K., Stephen, Q., Petawabano, B., Dannenbaum, D., et al. (2006). Beliefs and practices of first nation women about weight gain during pregnancy and lactation: Implications for women’s health. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 38, 102–119.

Wiles, R. (1998). The views of women of above average weight about appropriate weight gain in pregnancy. Midwifery, 14, 254–260.

National Center for Health Statistics. (1996). Supplements to monthly vital statistics report: Advance reports, 1988. Vital and Health Statistics, 24.

Simpson, C. (1998). Reaffirming our commitment to improving health services for Hispanics. Closing the gap: A newsletter of the Office of Minority Health V. 3, Editor. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Chasan-Taber, L., Schmidt, M. D., Pekow, P., Sternfeld, B., Solomon, C. G., & Markenson, G. (2008). Predictors of excessive and inadequate gestational weight gain in Hispanic women. Obesity (Silver Spring), 16, 1657–1666.

Pawson, I. G., Martorell, R., & Mendoza, F. E. (1991). Prevalence of overweight and obesity in US Hispanic populations. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 53, 1522S–1528S.

Kieffer, E. C., Carman, W. J., Gillespie, B. W., Nolan, G. H., Worley, S. E., & Guzman, J. R. (2001). Obesity and gestational diabetes among African-American women and Latinas in Detroit: Implications for disparities in women’s health. Journal of the American Medical Women’s Association, 56, 181–187, 196.

Becker, M. H., & Mainman, L. A. (1974). The health belief model and personal health behavior. Health Education Monographs, 2, 324–473.

Janz, N. K., & Becker, M. H. (1984). The health belief model: A decade later. Health Education Quarterly, 11, 1–47.

Krueger, R. A., & Casey, M. A. (Eds.). (2000). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Berger, B., & Motl, R. W. (2000). Exercise and mood: A selective review and synthesis of research employing the profile of mood states. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 12, 69–92.

Strychar, I. M., Chabot, C., Champagne, F., Ghadirian, P., Leduc, L., Lemonnier, M. C., et al. (2000). Psychosocial and lifestyle factors associated with insufficient and excessive maternal weight gain during pregnancy. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 100, 353–356.

Kiel, D. W., Dodson, E. A., Artal, R., Boehmer, T. K., & Leet, T. L. (2007). Gestational weight gain and pregnancy outcomes in obese women: how much is enough? Obstetrics and Gynecology, 110, 752–758.

Sabogal, F., Marin, G., Otero-Sabogal, R., & Marin, B. V. (1987). Hispanic familism and acculturation: What changes and what doesn’t? Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 9, 397–412.

Dipietro, J. A., Millet, S., Costigan, K. A., Gurewitsch, E., & Caulfield, L. E. (2003). Psychosocial influences on weight gain attitudes and behaviors during pregnancy. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 103, 1314–1319.

Stevens-Simon, C., Roghmann, K. J., & McAnarney, E. R. (1992). Relationship of self-reported prepregnant weight and weight gain during pregnancy to maternal body habitus and age. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 92, 85–87.

Bermudez, O. I., Falcon, L. M., & Tucker, K. L. (2000). Intake and food sources of macronutrients among older Hispanic adults: Association with ethnicity, acculturation, and length of residence in the United States. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 100, 665–673.

Gollenberg, A., Pekow, P., Markenson, G., Tucker, K. L., & Chasan-Taber, L. (2008). Dietary behaviors, physical activity, and cigarette smoking among pregnant Puerto Rican women. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 87, 1844–1851.

Balcazar, H., Krull, J. L., & Peterson, G. (2001). Acculturation and family functioning are related to health risks among pregnant Mexican–American women. Behavioral Medicine, 27, 62–70.

Evenson, K. R., Sarmiento, O. L., Macon, M. L., Tawney, K. W., & Ammerman, A. S. (2002). Environmental, policy, and cultural factors related to physical activity among Latina immigrants. Women and Health, 36, 43–57.

Polley, B. A., Wing, R. R., & Sims, C. J. (2002). Randomized controlled trial to prevent excessive weight gain in pregnant women. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders, 26, 1494–1502.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tovar, A., Chasan-Taber, L., Bermudez, O.I. et al. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Beliefs Regarding Weight Gain During Pregnancy Among Hispanic Women. Matern Child Health J 14, 938–949 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-009-0524-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-009-0524-8