Abstract

Objective To evaluate the efficacy of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria using sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) in the prevention of anaemia in women of low parity in a low socio-economic, malaria endemic setting. Method The study design was an open randomized control trial comparing anaemia incidence among pregnant women on intermittent presumptive treatment of malaria with SP with those on chloroquine (CQ). A total of 352 primigravid and secondigravid women between 16 and 30 weeks gestation receiving antenatal care at the Primary Health Care Center, Enuwa in Ile-Ife, Osun State, Nigeria were serially recruited and randomly allocated into experimental and control groups of 176 each. The experimental group received SP (to a maximum of three doses depending on the gestational age at enrollment into the study) while the control group had treatment doses of CQ at recruitment and subsequently only if they had symptoms suggestive of malaria. The primary outcome measure was anaemia (haematocrit < 30) at 34 weeks of gestation. Result At recruitment and 34 weeks gestation, there was no statistically significant difference between the experimental and control group in terms of socio-demographic characteristics and past medical history. Thirty-three (22.6%) and 52 (37.1%) women in the study and control groups, respectively, had anaemia (protective efficacy 49.5%, p = 0.01). With multivariate analysis, controlling for the possible confounding effects of education, parity, haemoglobin level at booking and malaria parasitaemia in peripheral blood, the difference in the incidence of anaemia in the two groups remained significant (p = 0.01; odds ratio = 0.5; 95% confidence interval = 0.29–0.85). Conclusion The IPT regime with sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine is an effective, practicable strategy to decrease risk of anaemia in women of low parity residing in areas endemic for malaria.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Malaria is an important public health problem, particularly in Africa, south of the Sahara, where climatic factors, poor environmental sanitation and cultural habits provide conditions whereby the parasite can be transmitted throughout the year. Malaria is currently transmitted in over 100 countries in the tropics and subtropics with over two billion people or 40% of the world’s population permanently at risk of infection [1]. It is estimated that 90% of the annual 500 million cases of malaria occur in sub-Saharan Africa, where 80% of the estimated 1.5–3.0 million annual deaths are due to malaria [2]. In Nigeria, at least 50% of the population experience an episode of malaria annually, with under-five children and pregnant women at greater risk of the debilitating effects of the infection [3]. According to the Federal Ministry of Health, malaria accounts for 30% of childhood mortality and 11% of maternal deaths in Nigeria [3].

Malaria is particularly a challenge in pregnancy because acquired immunity to malaria is precariously established and it is liable to break down under conditions of stress such as pregnancy. Pregnant women have attacks of malaria more frequently and more severely than non-pregnant women from the same area and they are more likely to die from complications of malaria [4]. Malaria has severe negative implications for pregnancy outcomes, including incidence of miscarriages [5] and delivery of low birth weight babies [6, 7].

One of the major challenges of malaria among pregnant women is the higher risk of maternal anaemia [8, 9]. Anaemia in pregnancy has been reported as being responsible for up to 20% of maternal deaths in some hospital series in sub-Saharan Africa [7]. Women of low socio-economic class are known to have higher incidence of anaemia in pregnancy. The depression of malaria immunity in pregnancy with its attendant risks of maternal anaemia and delivery of low birth weight babies are most marked in first pregnancies and decreases with increasing gravidity [10]. Studies in Zambia have detected more malaria parasites in placentas of primigravid women than in those of multiparous women [11]. Also, an investigation in The Gambia found placental malaria three times as often in primiparous women compared to women with three child births or more [12].

Since many malaria episodes are symptomless, treatment of symptomatic episodes miss a sizeable proportion of infections. Moreover, many peripheral blood slides of pregnant women may be negative despite the presence of sequestered parasites in the placenta [7]. Malaria prevention in pregnancy through the use of chemoprophylaxis is associated with reduced incidence of low birth weight [13–15], less placental parasitaemia [16] and higher mean maternal haemoglobin [17]. Such prophylaxis may also prevent severe haemolytic anaemia [17, 18]. However, while chemoprophylaxis may be highly effective in preventing disease, it does not prevent infection and also has some potential drawbacks. These drawbacks include poor compliance, cost, and impairment of development of natural immunity to malaria.

The current strategy for malaria control in pregnancy is intermittent preventive treatment (IPT)—an approach whereby pregnant women are treated for malaria presumptively (i.e. without diagnosis) with curative doses of effective antimalarials at regular intervals during the second and third trimester [19]. While both sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) and chloroquine (CQ) can be used for IPT, SP has a simpler regime: thus, the administration of incorrect dosages, which proved common with chloroquine, may occur less frequently with SP [19]. Troublesome side effects such as body itching also occur less frequently with SP. However, there is a potential risk of congenital defects occurring with the use of SP in the first trimester because of the possible association of anti-folate drugs with congenital defects [20, 21]. Despite the practical advantages of SP for IPT, its use for this purpose remains relatively unpopular in Nigeria and studies on IPT effectiveness in Nigerian population are rare.

Materials and Methods

The study was a randomized, open (single blind) clinical trial involving comparison of IPT with sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) and chloroquine (CQ) administered in line with the new national protocol for managing malaria in pregnancy. The study was conducted in Primary Health Care, Enuwa in Ile-Ife, Osun state, South-West Nigeria. This centre is the headquarters of primary health care activities in Ife Central Local Government Area, and the biggest primary health care facility under the jurisdiction of the local government. The catchment population of the health centre consists mainly of the indigenous population of Ile-Ife, who mostly belong to the low socio-economic class.

Recruitment of Study Participants

The target population of the study were primigravid and secondigravid women (women carrying their first or second pregnancy). Recruitment into the study took place between October 2003 and March 2004. Those recruited were first time antenatal clinic (ANC) attendees between 16 and 30 weeks of pregnancy who voluntarily consented to participate in the study. Eligible pregnant women with any of the following conditions were however excluded: multiple pregnancies, haemoglobin below 6 g/dl at recruitment; severe pre-eclampsia, clinical diagnosis of malaria at presentation, sickle cell anaemia, history of reaction to sulphur-containing drug or chloroquine and previous history of unfavourable pregnancy outcome such as spontaneous abortion or still birth.

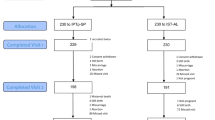

Sample size was determined using computer programs for epidemiologists (PEPI), version 3.01 [22]. Based on a study of Shulman et al. [7] that reported values of 14.5% and 27.3% for proportion of anaemia in women using SP and CQ, respectively, and using a 90% confidence level, a power of 80% and a study-to-control group ratio of 1:1, a minimum sample size of 246 subjects—123 per group was determined. To compensate for possible loss to follow up, a correction factor of 20% was used to increase the sample size. Eligible pregnant women who consented to participate were recruited serially until the desired sample size was achieved.

Randomisation of Study Participants and Administration of Drugs

The subjects were randomised into study and control groups using simple (unrestricted) randomization method. This allocation method involved a ballot system whereby each participant picked a piece of folded paper (which has the group allocation specified) out of a bag.

The experimental group received a regimen of between one and three treatment doses of sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine in the second and early third trimester depending on gestational age at recruitment. Doses were given at intervals of 4 weeks with the last dose given at 30 weeks. All doses were administered under direct observation during clinic visits. Members of the control group were treated with chloroquine at booking presumptively and thereafter with chloroquine whenever they had symptoms of malaria in line with the national treatment protocol. The study protocol allowed for women who developed severe malaria needing treatment with other antimalarial drugs to drop out of the study but none of the study participants developed such. All the participants received routine haematinics as well as other components of routine pregnancy-related care at each antenatal clinic visit.

Data Collection

At recruitment, duration of gestation was assessed by the date of last menstrual period and by ultrasonography when in doubt. Relevant socio-demographic and health information of participants were collected using structured questionnaires at recruitment and during the follow-up period. Medical information collected included past and present obstetrics history, history of drug use and drug reactions, and types of antimalarials and other drugs received outside the study protocol. Haemoglobin concentrations of individual women were assessed by determining the packed cell volume (PCV). Anaemia was defined as PCV less than 30. Presence of malaria parasite was determined through thick blood films stained with Giemsa, using standard method as described by Cheesbrough [23]. The data collectors and laboratory technologists who analysed the blood samples were blinded to the groups to which the participants belonged.

Data Analysis

Data management was carried out using SPSS statistical software version 11.0. The basic demographic factors and obstetric histories of the treatment and control groups were compared for statistically significant differences using Chi-square test. Association between the outcome variable (anaemia at 34 weeks of gestation) and type of antimalarias used was determined using bivariate analysis. Multivariate analysis (binary logistic regression) was conducted to control for possible confounding effect of age, parity, level of education, haemoglobin level at booking, and presence of malaria parasiteamia in the blood at 34 weeks; the odds ratio and 95% confidence interval (CI) were thereby obtained. In addition, the risk ratio for anaemia was calculated for both the experimental and control group and protective efficacy of SP compared with chloroquine for anaemia was calculated from the risk ratio using the formula, protective efficacy = 1-relative risk [24]. Statistical significance was determined at 5% level for relevant analyses.

Ethical Issues

Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the Ethics and Research Committee of the Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospitals Complex, Ile-Ife. Consent was voluntarily obtained from each of the participants following detailed explanation of the nature, scope and demands of the study. Prospective participants were assured that non-participation in the study would not affect the type and/or standard of treatment to be given to them at the facility. The study was designed to stop at 34 weeks gestation to ensure prompt treatment of any participant that may be found to be anaemic in order to reduce the likelihood of severe anaemia at the time of delivery. Plans were put in place for an obstetrician from the maternity unit of the Obafemi Awolowo Teaching Hospital Complex Ile-Ife to promptly see any of the participants that may develop illness during the study.

Results

Table 1 presents selected socio-demographic characteristics of women randomly allocated into study and control groups. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in terms of their age distribution, educational level, marital status and parity (p > 0.05). There was also no statistically significant difference between the groups with respect to gestational age at booking and presence of anaemia at recruitment.

One hundred and forty-six members of the experimental group (83%) and 140 members of the control group (79.5%) were successfully followed up until 34 weeks of gestation. At 34 weeks of gestation, no statistical significant difference was observed between the socio-demographic characteristics of the treatment and control groups (Table 2).

As Table 3 shows, 22.6% of the experimental group had anaemia at 34 weeks compared to 37.1% of the control group. The difference in the incidence of anaemia was highly significant statistically (χ2 = 7.23; p < 0.01). The association between the occurrence of anaemia and antimalarial treatment received remained significant when respondents were stratified by gestational age at recruitment (Mantel-Haenszel Chi-square, p = 0.01) (Table 4). The protective efficacy of IPT against anaemia (in comparison with chloroquine) was 49.5%.

When the possible confounding effect of age, parity, level of education, haemoglobin level at booking, and presence of malaria parasiteamia in the blood at 34 weeks was controlled for using binary logistic regression, the statistically significant difference in the effect of SP compared to that of chloroquine in the prevention of anaemia in pregnancy still remained (p = 0.01). In fact, only the study status (i.e. type of antimalarial drug received) was shown to be statistically significant as an explanatory variable for anaemia in pregnancy. The chance of anaemia being recorded at term among pregnant women using SP for IPT was half that of women given chloroquine (OR = 0.50; 95% CI = 0.29–0.85) (Table 5).

Discussion

Malaria is an important contributor to maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality in Nigeria and other tropical countries, even as anaemia remains a major challenge in the safe motherhood arena in these countries. Our study on efficacy of IPT with SP on anaemia had focused on women who are at higher risk of malaria complications as well as higher risk of anaemia—low parity women in a low socio-economic setting.

The result showed that pregnant women who had IPT with sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine had a statistically significant lower rate of anaemia compared to those who received chloroquine at 34 weeks. A similar finding was reported in a study carried out in Malawi where the use of sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine was also associated with higher maternal haematocrit [25]. Our result also agreed with that of Shulman and colleagues in Kenya [7] who demonstrated that IPT using sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine is effective in reducing the risk of anaemia in low parity pregnant women. While Shulman and his colleagues compared IPT with SP to a placebo, our approach, in view of ethical concerns regarding placebo-controlled trials, compared IPT with SP to CQ as nationally recommended for management of malaria in pregnancy. The differences in the drug regimen and other characteristics of the two drugs used made blinding of patients conceptually impossible, thus, necessitating an open control trial. However, with the blinding of data collectors and laboratory personnel, and the use of an objective end-point (haematocrit determination), the possibility of bias was minimised.

Our study approach was tailored to ensure conformity with the highest ethical standards and ensure participants’ safety. Among others, the administration of the antimalarial drugs was done starting from the second semester in line with the recommendation of the World Health Organisation that sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine be avoided during the first trimester of pregnancy because of possible association of anti-folate drugs with congenital defects. On the other hand, our study endpoint of 34 weeks gestation allows opportunity for definitive treatment of anaemia. While it is possible that other conditions such as hookworm and intestinal schistosomiasis contribute to the incidence of anaemia among populations in sub-Saharan Africa, randomisation of participants, as we had done, is expected to minimise possible confounding effects of such conditions.

Overall, the result of this study demonstrates the efficacy of IPT with sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine at reducing the development of anaemia in pregnancy in an area of endemic transmission and provides an evidenced-based template on which policymakers and health workers can intervene to reduce maternal mortality due to anaemia secondary to malaria in pregnancy. The simple regime of SP, its low cost, and the relatively low incidence of troublesome side-effects makes it highly acceptable to pregnant women and health workers. Although there is a small risk of severe adverse reactions to sulpha-containing drugs [20, 21], in an area with endemic malaria transmission and associated high level of malaria-attributable anaemia in pregnancy with its implications for negative pregnancy outcomes, the benefits of this regimen far out weighs this potential risk.

Conclusion

With its simple regimen, relatively good safety profile and possibility of direct observation of the use of the drug at the health clinic, IPT with sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine is an effective practicable strategy to reduce risk of anemia in low parity groups living in malaria endemic areas such as Nigeria.

References

Paxton, L. A., Slutsker, L., Schultz, L. J., Luby, S. P., Meriwether, R., Matson, P., & Sulzer, A. J. (1996). Imported malaria in Montagnard refugees settling in North Carolina: Implications for prevention and control. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 54, 54–57.

Malaria Foundation International. http://www.malaria.org. Accessed February 2003.

Federal Ministry of Health (Nigeria). (2004). Malaria control in Nigeria a strategy for behaviour change communication 2004–2005. Abuja: Federal Ministry of Health.

McGregor, I. A. (1984). Epidemiology, malaria and pregnancy. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 33, 517–525.

Malaria—A crisis with solutions. World Health Organisation. http://www.rbm.who.int/docs/AMD/factsheet.htm. Accessed 23 July 2005.

Brabin, B. (1991). The risks and severity of malaria in pregnant women. Applied Field Research in Malaria reports WHO; no 1.

Shulman, C. E., Dorman, E. K., Cutts, F., Kawuondo, K., Bulmer, J. N., Peshu, N., & Marsh, K. (1999). Intermittent sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine to prevent severe anemia secondary to malaria in pregnancy: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Lancet, 353, 632–636.

Schultz, L. J., Steketee, R. W., Chitsulo, L., Macheso, A., Kazembe, P., & Wirima, J. J. (1996). Evaluation of maternal practices, efficacy, and cost-effectiveness of alternative antimalarial regimens for use in pregnancy: Chloroquine and sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 55, 87–94.

Deen, J. L., Von Seidlein, L., Pinder, M., Walraven, G. E., & Greenwood, B. M. (2001). The safety of the combination artesunate and pyrimethamine-sulphadoxine given during pregnancy. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 95, 424–428.

Steketee, R. W., & Breman, J. G. (1988). Malaria infection in pregnant women in Zaire: The effects and potential for intervention. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology, 82, 113–120.

Van Dongen, P. W. J., & van’t Hof, M. A. (1983). Sickle cell trait, Malaria and anemia in pregnant Zambian women. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 77, 402–404.

Mc Gregor, I. A., Wilson, M. E., & Billewicz W. Z. (1983). Malaria Infection of the placenta in the Gambia, West Africa: Its Incidence and relationship to still birth, birth weight and placental weight. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 77, 232–244.

Wolfe, E. B., Parise, M. E., Haddix, A. C., Nahlen, B. L., Ayisi, J. G., Misore, A., & Steketee, R. W. (2001). Cost-effectiveness of sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine for the prevention of malaria-associated low birth weight. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 64, 178–186.

Mutabingwa, T. K., Malle, L. N., de Geus, A., & Oosting, J. (1993). Malaria chemosuppression in pregnancy. II. Its effects on maternal haemoglobin levels, placental malaria and birth weight. Tropical and Geographical Medicine, 45, 49–55.

Steketee, R. W., Wirima, J. J., Hightower, A. W., Slutsker, L., Heymann, D. L., & Breman, J. G. (1996). The effect of malaria and malaria prevention in pregnancy on offspring birth weight, prematurity and intrauterine growth retardation in rural Malawi. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 55, 33–41.

Cot, M., Roisin, A., Barro, D., Yada, A., Verhave, J. P., Carnevale, P., & Breart, G. (1992). Effect of chloroquine chemoprophylaxis during pregnancy on birth weight: Results of a randomized trial. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 46, 21–27.

Geelhoed, D. W., Visser, L. E., Addae, V., Asare, K., Schagen van Leeuwen, J. H., & van Roosmalen, J. (2001). Malaria prophylaxis and the reduction of anemia at child birth. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics, 74, 133–138.

Salihu, H. M., Naik, E. G., Tchuinguem, G., Bosny, J. P., & Dagne, G. (2002). Weekly Chloroquine prophylaxis and the effect on maternal hemoglobin status at delivery. Tropical medicine & international health, 7, 29–34.

WHO Expert Committee on malaria. (2000). Twentieth report. Geneva: World Health Organisation (WHO Technical report series, No 892).

Hernandez-Diaz, S., Werter, M. M., Walker, A. M., & Mitchell, A. A. (2000). Folic acid antagonists during pregnancy and the risk of birth defects. New England Journal of Medicine, 343, 1608–1614.

Czeizel, A. E., Rockenbayer, M., Sorensen, H. T., & Olsen, J. (2001). The teratogenic risk of trimethoprim-sulphonamides: A population based case control study. Reproductive Toxicology, 15, 637–646.

Gahlinger, P. M., & Abramson, J. H. (1999). Computer programs for epidemiologists: PEPI Version 3.01. Wales: Brixton Books.

Cheesbrough, M. District laboratory practice in tropical countries, Part 1 1998 (pp. 239–249).

Kirkwood, B. R., & Sterne, J. A. C. (2003). Essential medical statistics (2nd ed., p. 454). Oxford: Blackwell Science.

Rogerson, S. J., Chaluluka, E., Kanjala, M., Mkundika, P., Mhango, C., & Molyneux, M. E. (2000). Intermittent sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine in pregnancy: Effectiveness against malaria morbidity in Blantyre, Malawi. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 94, 549–553.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Asa, O.O., Onayade, A.A., Fatusi, A.O. et al. Efficacy of Intermittent Preventive Treatment of Malaria with Sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine in Preventing Anaemia in Pregnancy among Nigerian Women. Matern Child Health J 12, 692–698 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-008-0319-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-008-0319-3