Objective: Because postpartum hemorrhage may result from factors related to obstetrical practice patterns, we examined the variability of postpartum hemorrhage and related risk factors (obstetrical trauma, chorioamnionitis, and protracted labor) across hospital types and hospitals in California. Methods: Linked birth certificate and hospital discharge data from 507,410 births in California in 1997 were analyzed. Cases were identified using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes. Comparisons were made across hospital types and individual hospitals. Risk adjustments were made using 1) sample restriction to a subset of 324,671 low-risk women, and 2) Bayesian hierarchical logistic regression model to simultaneously quantify the effects of patient-level and hospital-level risk factors. Results: Postpartum hemorrhage complicated 2.4% of live births. The incidence ranged from 1.6% for corporate hospitals to 4.9% for university hospitals in the full sample, and from 1.4% for corporate hospitals to 3.9% for university hospitals in the low-risk sample. Low-risk women who delivered at government, HMO and university hospitals had two- to threefold increased odds (odds ratios 1.98 to 2.71; 95% confidence sets ranged from 1.52 to 4.62) of having postpartum hemorrhage compared to women who delivered at corporate hospitals, irrespective of patient-level characteristics. They also had significantly higher rates of obstetrical trauma and chorioamnionitis. Greater variations were observed across individual hospitals. Conclusion: The incidence of postpartum hemorrhage and related risk factors varied substantially across hospital types and hospitals in California. Further studies using primary data sources are needed to determine whether these variations are related to the processesof care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Postpartum hemorrhage is a major cause of maternal mortality and morbidities worldwide. While death resulting from postpartum hemorrhage is rare in developed countries, severe maternal morbidities may arise as a consequence of major blood loss (1). The most important complications include hypovolemic shock, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, renal failure, hepatic failure, and adult respiratory distress syndrome (2).

Some cases of postpartum hemorrhage may result from factors related to obstetrical practice patterns. For example, inappropriate labor induction (e.g., elective induction with unfavorable cervix) or inattentive labor management could lead to protracted labor, which is associated with increased risk for uterine atony (particularly with prolonged use of oxytocin). Protracted labor could also lead to chorioamnionitis, especially in the setting of prolonged rupture of membranes, frequent cervical examinations, internal monitoring, or operative deliveries (3–6). Chorioamnionitis also increases the risk for uterine atony, which is a leading cause of postpartum hemorrhage. Inappropriate or injudicious conduct of operative deliveries could lead to genital tract lacerations or obstetrical trauma, which could also result in postpartum hemorrhage. In some instances, postpartum hemorrhage may be the result of obstetrical practice patterns that led to protracted labor, chorioamnionitis, or obstetricaltrauma.

The purpose of this paper is to describe the variability of postpartum hemorrhage across hospitals in California. We hypothesized that such variability, if found, may be partially attributable to differences in the quality of obstetrical care. The primary aim of this paper is to examine variations in the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage across hospital types and individual hospitals in California. A secondary aim is to examine variations in the incidence of obstetrical trauma, chorioamnionitis, and protracted labor, three important risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage that may be related to obstetrical practice patterns.

METHODS

This study is part of a collaborative project to develop a statewide network for quality improvement in health services for pregnant women supported by the California Department of Health Services Maternal and Child Health Branch. Human subjects approval was obtained from the institutional review boards of the state and the authors' respective institutions prior to the start of thestudy.

We used data from the 507,410 births in California in 1997 for which birth certificates and maternal and neonatal hospital discharge data were linked (hereafter referred to as the full sample). The discharge data were provided by the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD) of California. In excess of 97% of neonatal records and 98% of maternal records were linked using methodologies described elsewhere (7–8). Cases of postpartum hemorrhage, obstetrical trauma, chorioamnionitis and protracted labor were identified using ICD-9-CM (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition, Clinical Modification) codes as defined in Table I. We also examined blood transfusion rates using ICD-9 ProcedureCodes 990–9909.

Our analyses were conducted in three stages. First, a descriptive analysis comparing postpartum hemorrhage rates across hospital types was conducted in the full sample. Hospital types were defined by hospital ownership according to OSHPD data categories: for-profit (corporate), non-profit, district, government, health maintenance organization (HMO), and university. Teaching status was indicated by the presence or absence of an obstetrics and gynecology residency training program, as identified by OSHPD (9). We also compared variations in the incidence of obstetrical trauma, chorioamnionitis, and protracted labor by hospitaltypes.

Second, because variations in postpartum hemorrhage rates may be attributable to differences in hospital case-mix rather than practice patterns, we restricted further analyses to a low-risk sample. Our methodological approach was designed to be consistent with that used by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) (10). In lieu of complex multivariate risk-adjustment techniques, we used restrictions to isolate a homogeneous low-risk population. In this low-risk sample, variations in postpartum hemorrhage rates would more likely be related to differences in obstetrical practice patterns than patient risk status. We excluded women who had a cesarean delivery without labor because we are making inferences about labor management and its relation to postpartum hemorrhage. We also excluded women with antepartum hemorrhage, abruptio placentae, and placenta previa (ICD-9-CM codes 641.x) as these are high-risk clinical conditions known to be associated with maternal hemorrhage. Additionally, we performed bivariate analyses of postpartum hemorrhage with 31 maternal, fetal or placental conditions, of which 23 were associated with postpartum hemorrhage at p < 0.10 level. Women with these conditions were also excluded from further analyses (Appendix A). Finally, we excluded women who delivered at hospitals with fewer than 200 deliveries per year because of the difficulty in extrapolating results to practice patterns in such low volumehospitals.

Following exclusions, we are left with a clinically-homogeneous subset of 324,671 women without major maternal, fetal, or placental complications and at relatively low-risk for postpartum hemorrhage who delivered at 285 hospitals in California in 1997. A descriptive analysis comparing the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage, obstetrical trauma, chorioamnionitis, and protracted labor across hospital types and hospitals was conducted in this low-risk sample. Further comparisons were made after the sample had been stratified by mode of delivery (vaginal, vacuum- or forceps-assisted, or cesarean).

Third, a Bayesian hierarchical logistic regression model was used to estimate the adjusted rates of postpartum hemorrhage, obstetrical trauma, chorioamnionitis, and protracted labor for each hospital. This two-level model consisted of two equations, estimated simultaneously. The first equation quantified the effects of patient-level risk factors, including age, race-ethnicity, parity, adequacy of prenatal care utilization (11), and prior cesarean deliveries. The second equation quantified the effects of hospital-level factors, including hospital types and teaching status. The coefficients for the hospital-level equation allowed us to calculate the odds ratios for postpartum hemorrhage by hospital types, controlling for patient-level factors and teaching status. The overall model allowed us to estimate the adjusted rates of postpartum hemorrhage and related risk factors for each hospital, while simultaneously adjusting for patient-level factors and hospital-level factors using two levels of random variations. Details of the hierarchical regression model are provided in Appendix B, and are well described in other areas of health services research (12–13). At the level of individual hospitals, we compared the observed and adjusted incidence of postpartum hemorrhage, obstetrical trauma, chorioamnionitis, and protracted labor for hospitals that ranked at the top and bottom deciles with respect to their postpartum hemorrhage rates.

RESULTS

Full Sample

Of the 507,410 births in California in 1997 for which birth certificates and maternal and neonatal hospital discharge data were linked, there were 11,985 cases of postpartum hemorrhage (2.36% of all births). The most common subtype was uterine atony (72%), followed by retained placenta (13%), delayed (or secondary) postpartum hemorrhage (11%), and postpartum coagulation defects (4%).

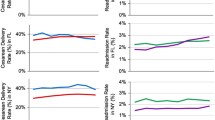

We found significant variations in the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage by hospital types in the full sample, ranging from 1.6% for corporate hospitals to 4.9% for university hospitals. As Fig. 1 illustrates, the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage was approximately 2.5 times higher among government and HMO hospitals, and three times higher among university hospitals, compared to corporate hospitals. Similarly, the blood transfusion rate was more than 1.5 times higher among government (0.41%) and HMO (0.44%) hospitals, and more than twice higher among university hospitals (0.6%), compared to corporate hospitals (0.26%).

Next we examined variations in the incidence of the three risk factors of postpartum hemorrhage (obstetrical trauma, chorioamnionitis, and protracted labor) in the full sample (Fig. 1). Hospital types with high incidence of postpartum hemorrhage also tended to have high rates of obstetrical trauma, chorioamnionitis, and protracted labor. University hospitals reported some of the highest rates, while corporate hospitals reported the lowest rates in all three. In fact, the incidence of obstetrical trauma and protracted labor was twice as high, and that of chorioamnionitis nine times as high, at university hospitals compared to corporate hospitals. Government and HMO hospitals also reported above-average rates of obstetrical trauma and chorioamnionitis.

Low-Risk Sample

In our low-risk sample of 324,671 women without major maternal, fetal, or placental complications, we identified 6668 cases of postpartum hemorrhage (2.05% of all births in the low-risk sample). The distribution of different subtypes of postpartum hemorrhage was similar to that observed in the full sample, with uterine atony accounting for the majority of cases.

In this low-risk population, we continued to find significant variations in the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage by hospital types, ranging from 1.4% for corporate hospitals to 3.9% for university hospitals (Fig. 2). However, we did not find significant variations in transfusion rates, which ranged from 0.13% for university and nonprofit hospitals to 0.17% for government and HMO hospitals (data not shown). We also found similar variations in the incidence of obstetrical trauma, chorioamnionitis, and protracted labor as in the full sample (Fig. 2). That is, university hospitals reported some of the highest rates and corporate hospitals the lowest rates for all three, while government and HMO hospitals also reported above-average rates for obstetrical trauma and chorioamnionitis.

When the sample was stratified by mode of delivery, similar patterns of variations were found (Table II). University hospitals reported some of the highest rates and corporate hospitals the lowest rates for postpartum hemorrhage and the three related risk factors, irrespective of the mode of delivery. Notably while government and HMO hospitals had relatively low rates of operative (instrumental and cesarean) deliveries, they reported high rates of postpartum hemorrhage, obstetrical trauma, and chorioamnionitis associated with these procedures. For example, while only 7% of low-risk births at HMO hospitals were delivered by vacuum or forceps, more than one in three (35%) of these deliveries were complicated by obstetrical trauma (Table II).

Bayesian Hierarchical Model

We attempted further risk adjustment in the low-risk population by using a Bayesian hierarchical logistic regression model. Table III presents the odds ratios for postpartum hemorrhage, obstetrical trauma, chorioamnionitis, and protracted labor by hospital types relative to corporate hospitals, adjusting for patient-level characteristics. Women who delivered at university hospitals had 2.7 times greater odds of postpartum hemorrhage as those who delivered at corporate hospitals, irrespective of patient-level risk factors. They were also 2.8 times as likely to experience obstetrical trauma, 3.5 times as likely to have chorioamnionitis, and showed a tendency toward increased risk for protracted labor, compared to women who delivered at corporate hospitals. Women who delivered at government and HMO hospitals were approximately twice as likely as those who delivered at corporate hospitals to have postpartum hemorrhage. They also had elevated risks of obstetrical trauma and chorioamnionitis relative to those delivered at corporate hospitals (Table III). When we added teaching status as a covariate to the model, similar odds ratios were obtained, except that university hospitals showed substantial decrements in odds ratios for postpartum hemorrhage (OR decreased from 2.71 to 2.30), chorioamnionitis (OR decreased from 3.45 to 2.81), and obstetrical trauma (OR decreased from 2.84 to 2.54). Government and HMO hospitals also showed substantial decrements in odds ratios for chorioamnionitis. Overall teaching status was independently associated with a threefold (OR = 3.10; 95% Confidence Set = 2.18, 4.38) increase in the odds of chorioamnionitis (data not shown).

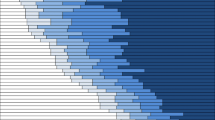

Lastly we examined variations in the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage at the level of individual hospitals. Table IV presents both observed and adjusted incidence of postpartum hemorrhage for the 29 hospitals (top decile) that had the highest adjusted rates of postpartum hemorrhage. The observed incidence of postpartum hemorrhage in these 29 hospitals ranged from 3.9 to 10.4%, and the adjusted incidence for a low-risk reference group (Caucasian women under 35 years of age with adequate or adequate plus prenatal care who are multiparous with no prior Cesarean delivery) using hierarchical regression analyses still ranged from 3.8 to 8.6%. While government, HMO and university hospitals were disproportionately represented in the top decile, the list of hospitals with exceptionally high postpartum hemorrhage rates included all types of hospitals (Table IV). The average incidence of postpartum hemorrhage for these 29 hospitals was 6.4%, more than three times higher than the state average and nearly 19 times higher than that of hospitals in the bottom decile. The average rates of obstetrical trauma, chorioamnionitis, and protracted labor for the 29 hospitals with the highest postpartum hemorrhage rates were 2.0, 10.6, and 4.7 times higher, respectively, than those among the 29 hospitals with the lowest incidence of postpartum hemorrhage.

DISCUSSION

Our study found substantial variations in the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage across hospital types and hospitals in California. Even after risk adjustment using a Bayesian hierarchical regression model, we continued to find greater than two- to threefold differences in the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage across hospital types. Variations in postpartum hemorrhage rates were even more striking across individual hospitals than across hospitaltypes.

The reasons for such wide variations in postpartum hemorrhage rates across hospital types and hospitals are not known. We hypothesized that such variability may reflect, in part, differences in the quality of obstetrical care. For example, improper or inexperienced conduct of operative deliveries could result in obstetrical trauma leading to postpartum hemorrhage. Hospitals with high incidence of postpartum hemorrhage also reported high rates of obstetrical trauma. Low-risk women delivering at university hospitals had 2.7 times the odds of postpartum hemorrhage, and 2.8 times the odds of obstetrical trauma, compared to those delivering at corporate hospitals. The decrement in odds ratios with the addition of teaching status as a covariate suggests that some, but not all, of the increased risk for postpartum hemorrhage and obstetrical trauma at university hospitals may be attributable to their teaching programs. Despite their relatively low volumes of operative deliveries, government and HMO hospitals reported exceptionally high rates of obstetrical trauma associated with these procedures. While we could not exclude the possibility of over-reporting, these results merit further investigation.

Similarly, hospitals with high incidence of postpartum hemorrhage also reported high rates of chorioamnionitis and protracted labor. For example, low-risk women delivering at government, HMO, and university hospitals had greater than two- to threefold increased odds of chorioamnionitis compared to those delivering at corporate hospitals, irrespective of patient-level risk factors. The 29 hospitals with the highest rates of postpartum hemorrhage also reported, on average, approximately ten times higher incidence of chorioamnionitis, and nearly five times higher rates of protracted labor, compared to the 29 hospitals with the lowest rates of postpartum hemorrhage. Inappropriate labor induction, inattentive labor management, and non-judicious use of oxytocin or internal monitoring are just a few of a number of obstetrical practices that could increase the risk for protracted labor and chorioamnionitis, which could then result in uterine atony and postpartum hemorrhage (3–6).

Our findings are subject to several limitations. First, variations in the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage may be due to information bias rather than actual differences in the quality of care. Previous studies have shown that clinical estimation of peripartum blood loss could be quite imprecise and variable, with a tendency toward underestimation (14). Different standards may be applied toward making the diagnosis (1). Reported incidence of postpartum hemorrhage in the literature ranged from 0.7 to 29% largely because different standards were used to define postpartum hemorrhage (3, 4, 15–16). Some have proposed using erythrocyte transfusion as a more objective measure of postpartum hemorrhage (3–5), but different protocols may exist among hospitals for postpartum transfusion. We found that while transfusion rates by hospital ownership corresponded to postpartum hemorrhage rates in the full sample, this was not the case in the low-risk sample, reflecting perhaps differences in the standards used across hospitals in the decision-making regarding blood transfusion, particularly in low-risk, healthy women. Hospitals may have different incentive structures (including billing) for coding and reporting. The intensity of case ascertainment may vary based on available information technologies in the hospitals. Systematic differences in diagnosis, coding and reporting, and case ascertainment could lead to information bias, resulting in over-reporting by some hospitals and under-reporting by others. Before making inferences about quality of obstetrical care, validation of these administrative data is needed. We have begun a pilot validation study at several hospitals in California.

Second, variations in the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage may be due to selection bias resulting from differential case-mix across hospital types and hospitals. That is, hospitals with higher rates of postpartum hemorrhage may just be caring for higher-risk women rather than delivering poorer quality care. While we attempted risk adjustment by restricting our sample to low-risk women without major maternal, fetal or placental complications, and by further adjusting for patient-level characteristics and teaching status using Bayesian hierarchical regression modeling, our model may still be underspecified, and unmeasured differences in patient case-mix across hospital types and hospitals may still account for differences in postpartum hemorrhage rates.

These potential biases underscore the limitations of using administrative data for quality monitoring purposes. Our study highlights significant differences in reported outcome, but it says little about the processes of care (17). For example, our data provide no information about indications for induction and cervical status at the time of induction, rupture-of-membranes-to-delivery time, use of oxytocin or other induction agents, availability of in-house obstetricians and anesthesiologists, indications for and conduct of operative deliveries, active management of labor or other process variables that may impact on postpartum hemorrhage and their related risk factors. Primary data collection about the actual processes of care is needed for quality monitoring.

In conclusion, we found significant variations in the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage and related risk factors (obstetrical trauma, chorioamnionitis, and protracted labor) across hospital types and hospitals. While our study calls attention to these important variations, we caution against making judgments about quality of care using administrative data. Our next steps are to determine whether these variations are real (rather than due to information or selection biases), and whether they are related to the processes of care. Further studies are needed to determine whether systematic differences in the quality of obstetrical care contributed to our findings of wide variations in postpartum hemorrhage across hospitals in California.

References

Mousa HA, Walkinshaw S. Major postpartum haemorrhage. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2001;13:595–603.

Bonnar J. Massive obstetric haemorrhage. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2000;14:1–18.

Combs CA, Murphy EL, Laros RK Jr. Factors associated with postpartum hemorrhage with vaginal birth. Obstet Gynecol 1991;77:69–76.

Combs CA, Murphy EL, Laros RK Jr. Factors associated with hemorrhage in cesarean deliveries. Obstet Gynecol 1991;77:77–82.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Postpartum hemorrhage. ACOG Educational Bulletin. Number 243, January 1998.

Casey BM, Cox SM. Chorioamnionitis and endometritis. Infect Dis Clin North Am 1997;11(1):203–22.

Herrchen-Danielsen B, Gould JB. User manual and technical report: Linkage of vital statistics linked birth/infant death, infant, and maternal hospital discharge file. Berkeley: UC Berkeley, 1996.

Herrchen-Danielsen B, Gould JB, Nesbitt TS. Vital statistics linked birth/infant death and hospital discharge record linkage for epidemiological studies. Comput Biomed Res 1997;30:290–305.

Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD). California Graduate Medical Education Programs, 1996–1997 update. Sacramento, CA: OSHPD, 1998.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. AHRQ quality indicators—Guide to inpatient quality indicators. Rockville, MD: AHRQ Publication 03-R203, 2003.

Kotelchuck M. An evaluation of the Kessner Adequacy of Prenatal Care Index and a proposed Adequacy of Prenatal Care Utilization Index. Am J Public Health 1994;84:1414–20.

Spiegelhalter DJ, Thomas A, Best NG, Lunn D. WinBUGS: Bayesian inference using Gibbs Sampling for Windows, Version 1.4. Cambridge, UK: MRC Biostatistics Unit, 2003.

Gatsonis CA, Epstein AM, Newhouse JP, Normand SL, McNeil BJ. Variations in the utilization of coronary angiography for elderly patients with an acute myocardial infarction: An analysis using hierarchical logistic regression. Med Care 1995;33:625–42.

Prasertcharoensuk W, Swadpanich U, Lumbiganon P. Accuracy of the blood loss estimation in the third stage of labor. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2000;71:69–70.

Waterstone M, Bewley S, Wolfe C. Incidence and predictors of severe obstetric morbidity: Case-control study. BMJ 2001;322:1089–94.

Hill JA, Fadel HE, Nelson MC, Nelson RM, Nelson GH. Blood loss at vaginal delivery. South Med J 1986;79:188–92.

Donabedian A. Promoting quality through evaluating the process of patient care. Med Care 1968;6:181–202.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial support for this work was provided by the California Department of Health Services Maternal and Child Health Branch (Contract No. 01-15166).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

APPENDIX A: MATERNAL, FETAL, OR PLACENTAL CONDITIONS EXCLUDED FROM THE LOW-RISK SAMPLE

-

Asthma

-

Congenital fetal CNS anomaly or chromosomal abnormality

-

Diabetes or abnormal glucose tolerance

-

Herpes

-

Intrauterine fetal demise

-

Intrauterine growth restriction

-

Macrosomia

-

Malpresentation

-

Maternal cerebral hemorrhage

-

Maternal congenital and other heart disease

-

Maternal hypotension or obstetrical shock

-

Maternal renal abnormalities

-

Maternal soft tissue disorder

-

Maternal thyroid abnormalities

-

Mental disorder

-

Multiple gestation

-

Oligohydramnios

-

Other types of hypertension

-

Polyhyramnios

-

Preterm gestation

-

Pulmonary embolism

-

Severe hypertension: severe pre-eclampsia or eclampsia

-

Uterine rupture

APPENDIX B: BAYESIAN HIERARCHICAL LOGISTIC REGRESSION MODEL USED TO ESTIMATE THE ADJUSTED RATES OF POSTPARTUM HEMORRHAGE, OBSTETRICAL TRAUMA, CHORIOAMNIONITIS, AND PROTRACTED LABOR FOR INDIVIDUAL HOSPITALS

The probability of each of the four events (postpartum hemorrhage, protracted labor, chorioamnionitis, and obstetrical trauma) was modeled using hierarchical logistic regression models. This modeling framework facilitates the analysis of provider variations in outcomes by separating provider-related factors from patient-related ones. The model consists of two equations that are simultaneously estimated, one (patient level) to model within hospital variability, and the other (hospital level) to model between hospital variability. For each dichotomous outcome, the hierarchical logistic regression equations are as follows:

P(Y ij = 1) = P ij is the Bernoulli probability of an event for patient i in hospital j.

-

1.

Patient level equation:

Logit (P ij ) = β 1 j + β 2 j (Age ≥ 35) ij + β 3 j (Poor PNC) ij + β 4 j (Asian) ij + β 5 j (African American) ij + β 7 j (Hispanic) ij + β 8 j (Native American) ij + β 9 j (Nulliparous) ij + β 10 j (Prior CS) ij

Covariates include age, race-ethnicity, parity, prenatal care utilization (10), and prior cesarean delivery. The reference group consists of Caucasian women less than 35 years of age, with adequate or adequate-plus prenatal care, multiparous with no prior cesarean delivery. The beta coefficients from this logistic regression (log-odds scale) measure the effect of patient characteristics on outcome within hospital j. The intercept β 1 j is the baseline (for the reference group) event rate for hospital j and the other β slopes measure the effects of the covariates on outcome.

-

2.

Hospital level equation:

β j is distributed multivariate normal with mean μ and variance–covariance matrix D (bold parameters are multi-dimensional) where,

$$\mu = \gamma _1 + \gamma _2 ({\rm Government})_j + \gamma _3 ({\rm District})_j\\\quad +\, \gamma _4 ({\rm HMO})_j + \gamma _5 ({\rm Not}\;{\rm for}\;{\rm profit})_j \\ \quad +\,\gamma _6 ({\rm UC})_j + \gamma _7 ({\rm Other}\;{\rm hospital}\;{\rm covariates}\;\\\qquad {\rm such}\; {\rm as}\;{\rm OB}\;{\rm teaching}\;{\rm status})_j$$

Covariates for the hospital-level equation include indicator variables for hospital ownership and OB teaching status. The intercept γ 1 is a reference parameter representing corporate hospitals (none of which are obstetrics teaching hospitals).

We assume that the hospital-specific parameter β j is a multivariate normal variate with mean μ that is linearly related to the hospital characteristics. The components of μ are therefore hospital class expectations given the class characteristics. The γ's are parameters common to all hospitals, measuring the effect of hospital characteristics on the expected hospital class rate of outcome. In other words, the components of γ link between hospital characteristics and hospital-specific effects. While the β j are directly related to the patient covariates, the γ's are directly related to hospital level covariates. Note that not only mean hospital rate of outcomes (β intercepts) may vary by hospital characteristics but also β slopes are allowed to vary by hospital characteristics.

The model was estimated under a Bayesian framework that assigns prior probability distributions to all unknown parameters (specifically to γ and D). Posterior distributions of the model parameters (conditional on the data) were derived using Markov Chain Monte Carlo methodology. For each outcome a single Gibbs sampler string was used for inference, implemented using the WinBUGS software (5), with a burn-in of 1000 iterations and a further 2000 iteration used for inference. Starting values for parameters were calculated using logistic regression models. Estimated posterior means for odd ratios are reported with significance determined using 95% confidence sets.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, M.C., Fridman, M., Korst, L.M. et al. Variations in the Incidence of Postpartum Hemorrhage Across Hospitals in California. Matern Child Health J 9, 297–306 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-005-0009-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-005-0009-3