Abstract

While political and scientific interests in ecosystem services (ES) information increases, actual implementation in planning still remains limited. We investigated how landscape and regional planners in Germany already use environmental information, and explored their perceptions concerning an integration of additional information on ES in their work. Four themes are addressed: (1) existing decision-making contexts, (2) current use of environmental information, (3) perceived options for integrating ES information, and (4) useful ES information formats. The research method consists of semi-structured interviews and a web-based survey with German landscape and regional planners. Results are disaggregated between landscape and regional planners, as well as planners with and without prior knowledge of the ES concept. Our results illustrate that a broad range of environmental information is already used that could be associated with ES, but the two most frequently consulted data, species and habitats, relate more to biodiversity. Stronger integrating ES information in planning was generally perceived as useful. However, implementation would often require a mandate from higher-ranking policy levels and the provision of appropriate resources. Project-oriented planning, public information and regional development were seen as promising application contexts. Contrary to our expectations, planners with prior knowledge of the ES concept did not evaluate the usefulness of ES information significantly more optimistic. No single optimal ES information format (ordinal, cardinal, economic valuation) emerged, but context-specific combinations were proposed. The results present valuable guidance for studies and assessments that aim at addressing the ES information needs and requirements of decision makers, and planners in particular.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Decision-makers increasingly ask for mainstreaming ecosystem services (ES) in policy and planning at various scales, e.g. the European Commission (2011) in its Biodiversity Strategy to 2020 requests the Member States to map and assess the state of ecosystems and their services in their national territory by 2014. At the same time, scientists have developed a wide range of concepts and methods for ES mapping, quantification and valuation and apply them in a growing number of case studies around the world (Burkhard et al. 2012; Brouwer et al. 2013). Targeted spatial planning can play a key role in bringing scientific understanding to bear in practical efforts to conserve and sustainably use ES, as illustrated by the results of the UK National Ecosystem Assessment (Bateman et al. 2013).

However, the actual implementation of ES in concrete spatial and environmental planning and management practice still remains limited (cf. e.g. Plieninger et al. 2010; Primmer and Furman 2012; Hauck et al. 2013a). This is particularly the case for the implementation at landscape scale which has been interpreted as most relevant for sustainable development (Kates and Parris 2003; Wiek et al. 2006; Selman 2012). A key reason of this science-practice disconnect is the focus of most ES-studies and assessments on biophysical accounting or monetary valuation, and a lack of integration within a social process (Cowling et al. 2008; Daily et al. 2009). Bridging the science-practice gap and enhancing ES application in planning and management is a key research priority (Opdam et al. 2013) and poses several challenges (de Groot et al. 2010; Opdam 2010; Burkhard et al. 2010, 2012), for example due to the complexity of many ES studies (Koschke et al. 2012) and the need to adapt each study to the specific decision-context and scale (Scolozzi et al. 2012). Only very recently, first scientific projects have started to explore options for more specifically integrating landscape and ES into planning and management, also at local to region scales (Termorshuizen and Opdam 2009; Wittmer and Gundimedia 2012) and within Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) (Geneletti 2013; Helming et al. 2013).

The objective of this paper is to investigate the current use of environmental information by landscape and regional planners in Germany, and to explore their perceptions concerning an integration of additional information on ES in their work. Our analysis addresses four themes: (1) What are landscape and regional planners’ key decision-making challenges that potentially yield impacts on ecosystems? (2) Which information on existing values and potential impacts on ecosystems do they (already) use as decision-support, and what are information constraints? (3) In which planning processes would planners like to integrate information on ES, and what is the expected added value? (4) Which kind of ES formats would be useful for different types of decision processes? The results of our study could be an important input for studies and assessments that want to address the ES information needs and requirements of decision makers, and planners in particular.

Below we briefly introduce the German planning context and describe our research methodology and data sources that we used to answer the questions. We then report our findings and explore their implications for the application of ES information in different application contexts in regional and landscape planning in Germany. Finally, we propose questions to be considered in future studies for developing useful ES information for decision-support.

The context: Spatial and landscape planning in Germany

As this paper concerns opportunities and challenges of integrating ES information in regional planning in Germany, it is necessary to clarify the meaning of some important terms (cf. ARL 2005, 2011):

Spatial planning has the task of building upon and integrating the interests of the different sectors that have an impact on space, in particular transport, energy, environmental, waste and water management. Spatial planning considers sectoral interests, and synthesizes them into a comprehensive planning proposal. Both, sectoral planning and spatial planning, are executed at four hierarchical levels, i.e. on the community, county, federal state and—only in the form of spatially unspecific, general recommendations—the national level.

Regional planning is spatial planning at the county level (equivalent with the NUTS 3 classification). This level was chosen as the scope of analysis for this paper because it usually concerns spatial areas that are sufficiently large to study and address ecosystem processes, capacities and services while at the same time allowing for sufficiently detailed assessments concerning single plots of land. At this level, the task of regional planning is to determine the desired future course of spatial development by proposing a regional plan. In addition, some counties issue informal and voluntary regional development concepts. These concepts describe how social and economic regional objectives could be achieved through joint actions and coordination across sectors.

At the county level, the sectoral plan that addresses environmental issues is termed ‘landscape framework plan’. It provides spatially explicit information and evaluations about a broad range of capacities of the environment and proposes nature conservation objectives and appropriate management measures to attain them. In doing so, landscape planning aims to safeguard the provision of landscape functions (Neef 1966; Haase 1978; von Haaren 2004), a concept similar to ES. However, the ES and landscape functions concepts differ in that the former often provides accountings of service delivery and more explicitly links to human demands (von Haaren and Albert 2011; Albert et al. 2012a; Bastian et al. 2012).

Besides the development of regional plans that integrate sectoral plans and comprehensively address the respective county, regional planners are involved in contributing to decision-making in more program- or project-related instruments such as strategic environmental assessment (SEA), environmental impact assessment (EIA), and environmental impact regulation (EIR). While SEA investigates the environmental implications of usually public plans and programs (Fisher 2007), EIA focuses on projects such as the proposed construction of a new highway and includes studies of alternative implementation options and their respective impacts on the environment. EIR, institutionalized by the German National Conservation Act, requires a project developer to desist from any unnecessary damage to nature and the landscape, and to take mitigation and replacement measures to compensate for any unavoidable damage.

‘Weighing of interests’ is a decision support procedure required by German law on administrative processes. It means to weigh conflicting interest, as for example expressed in different sectoral plans, against each other in a way that gives each of them fair consideration. So planners need to ensure that all interests are duly weighed, that no important interests have been neglected and that a proportionate balance has been found. If environmental interests expressed in landscape planning are rejected, a written statement has to be produced about the respective reasons. Public participation is part of the planning process. However, citizen and stakeholder comments are used to prepare the final decisions about the planning designations. The latter are taken not in a public interactive process but in a setting of political and administrative decision makers.

Methods

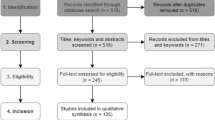

We followed a two stages research process to answer the key questions posed in the introduction. We first conducted interviews with thirteen key informants in April 2013. Key informants were regional and landscape planners from county or regional administrations of Hanover, Diepholz, Göttingen, Hildesheim, Northeim and Braunschweig in the federal state of Lower Saxony, Germany, responsible for implementing regional planning in their respective constituencies. The interviewees were identified based on their rich experience in spatial planning at the county scale and their openness towards new concepts.

The goal of these interviews was to gain contextualized insights into the perspectives of planners concerning issues related to our research questions. The key informant interviews were conducted according to the semi-structured interview method (Hay, 2005) and typically lasted 45–60 min. Interview data were collected through note taking. Answering schemes and language use amongst planners were extracted and served as basis for designing a web-based survey in the second research stage. The information gathered in the interviews is used here to illustrate commonalities and notable differences in information needs, pragmatic suggestions for improving information supply and use, and critical barriers to support improved decision making.

The conduct of a web-based survey formed the second stage of our research. It consisted of nine combined multiple choice and semi-structured questions (Supplementary material 1) which were structured in two sections: The first section concerned important decision contexts for landscape and regional planners, the source and types of environmental information that planners currently use, as well as perceived information deficit that planners see themselves confronted with. We also asked planners to state the three criteria perceived as most decisive in their weighing processes in order to investigate the relative importance of scientific environmental information in comparison with other, non-scientific considerations.

Only in the second part of the survey we introduced the concept of ES. We did this in order to avoid having only respondents that already were familiar with the ES concept. The second part of the questionnaire addressed three issues: Landscape and regional planners’ familiarity with the concept of ES (question 3a), their perceived usefulness and drawbacks of ES data and information in six application contexts (question 3b), and ES information formats that they would find useful (question 4). The application contexts were comprehensive planning, project-oriented planning, regional development, compensation schemes, scenario analyses and information for the public. Each context was illustrated by an example to enhance understanding. The investigation of useful information formats was based on the results of a method (von Haaren et al. 2011) to assess the ES “Climate protection” in terms of the potential CO2 retention or emission within agricultural fields in the region of Hanover, Germany. The results were illustrated in three different formats:

-

(a)

a qualitative description of the amount of service provided using a five-step ordinal (Lickert) scale from high retention to high emission,

-

(b)

a quantification of the amount of service provided on a cardinal scale (in t CO2/ha*a) and quantitative accounting for the region (Mio. t/agricultural area*a),

-

(c)

an estimate of the economic value of the amount of CO2 that was either emitted or retained, using the CO2 impact costs of 70€/t as suggested by UBA (UBA - Federal Environmental Agency 2008).

In order to provide some spatial reference, each format was supplemented by a map that illustrated the level of importance of each plot of land on an ordinal scale from very high potential retention to very high potential emission of CO2 (see von Haaren et al. 2011). The survey first provided the map and qualitative description and later added the quantitative estimate and the economic valuation. For each of these three formats, we asked survey participants to state perceived advantages and disadvantages.

The invitation to the online questionnaire was e-mailed during April and May of 2013. It was sent to 106 regional planning institutions which are specifically working on regional planning issues as identified by the German Spatial Planning and Research Organization—ARL (www.arl.net). We received 41 completed questionnaires, i.e. a relatively high turnout rate of about 38.7 %. Amongst these respondents were 30 regional planners, i.e. concerned with spatial planning, three landscape planners, i.e. focusing on environmental issues, and two respondents that worked in both areas. Six participants did not specify their background.

Several statistical methods, including Principle Component Analysis (PCA) and χ2, were tested to analyse the survey data for significant differences in the responses between different types of participants (e.g. landscape planners vs. regional planners and planners with or without prior knowledge of the ES concept). Due to large difference in the size of the subgroups, these analyses did not show obvious patterns. In consequence, the survey data was analyzed using simple statistical analyses, supplemented by qualitative insights from the open questions in the questionnaire and by the key informant interviews. In cases where differences in responses could be identified, we distinguish between landscape and regional planners, or between planners with and without prior knowledge of the ES concept, respectively.

Results

Decision contexts

Key informant interviews revealed that information needs and interests concern mainly weighing decisions between nature conservation issues and other interests in four areas: comprehensive spatial planning (e.g. regional plans, landscape framework plans), project-oriented planning procedures, regional development concepts, and assessments of different land use options. These findings where confirmed by the respondents of the survey who did not mention other decision making contexts beyond the four areas mentioned above. An example for such a weighing decision, frequently referred to by both interviewees and survey respondents, was the designation of areas for wind farms, where (economic) interests in renewable energy production have to be balanced with impacts on the visual landscape and avifauna. Another repeatedly mentioned problem is the designation of areas of the extraction of raw materials such as gravel or sand. Planning for infrastructure was also mentioned as often problematic.

‘Legal provisions and regulatory constraints’ as well as ‘recommendations from science and nature conservation’ were perceived as most decisive decision-making criteria perceived by the great majority of participating planners (Fig. 1). While ‘personal estimates’ were perceived as rather important in weighing processes by regional planners, this criterion does not seem to play a major role for landscape planners, who listed ‘acceptance by local land users’ as the third most important criterion.

Information used and information constraints

The most frequently consulted information sources, by both regional and landscape planners, were laws and directives as well as landscape plans, in accordance with the provisions and requirements of German spatial planning regulations (Fig. 2). The third most important sources were expert reports and opinions, which probably relate to the recommendations from science and nature conservation referred to as one of the most important decision making criteria (Fig. 1). Rather informal approaches such as discussions with colleagues and experts, internet searches, workshops and experiential knowledge were rather frequently used by regional planners but not so by landscape planners. Scientific publications are consulted by about half and one third of regional and landscape planners, respectively. Additional sources of information added by the respondents were insights gained from participation of nature conservation agencies in planning processes, as well as decisions by jurisdictional courts.

After identifying the sources of information consulted by respondents, we asked them to choose from a list the types of information used. The list was compiled in a twofold way, first it is based on the key informant interviews and second we added information about ES, however, avoiding mentioning the term ecosystem services itself (see Sect. “Research methods” as well as question 2a in Supplementary Material 1).

The results of the survey reveal that at least to some extend all ES types are already considered either in the regional or in the landscape plans (Fig. 3). However, the two information types consulted most frequently were data on species habitats and on the actual occurrence of species themselves. Cultural services, in particular aesthetics, tourism and recreation, also seem to be considered quite often. Species and habitats are seemingly used most frequently.

Information types on nature and landscape currently consulted by landscape and regional planners, organized according to an adapted version of the emerging CICES (http://cices.eu) and TEEB (2010) categories as well as biodiversity-related information

Additional information types that were added to our list were data on settlement development, special reports on nature protection and wind energy potential issues, as well as more site-specific ecological information.

Concerning the information availability, no significant differences were found for regional and landscape planners. Information was mostly available as maps (78.0 %). Semi-quantitative and descriptive data, e.g. concerning the landscape character of specific areas, was used by 63.4 % of respondents. Cardinally scaled estimates and accountings of services provision, for example based on a model simulation of groundwater recharge, were employed by 31.7 %.

Similar to the key informants, 75 % of respondents to the question of key information deficits and corresponding information needs complained about missing or outdated environmental data. The key shortcoming from the perspective of landscape planners was that landscape framework plans, usually the key source of environmental information, are often outdated and sometimes even nonexistent. Regional planners found the lack of comprehensive and current information on the presence of species was perceived as particularly problematic. One example, given repeatedly by key informants to illustrate the criticality of this type of information, is missing avifauna data needed in order to make weighing decisions about the acceptability of proposed wind farm sites. Further, corresponding to the importance of information on tourism and recreation (Fig. 3), important data shortages were seen concerning landscape character and landscape structures important for recreation. No other information deficits concerning ES were mentioned.

In addition to some of the key informants, three respondents from the survey found it problematic that often no prioritization of land uses is available that provides decision-making guidance. This poses a particular challenge in cases where conflicts between different land uses exist, even between alternative nature conservation objectives. Some key informants and one respondent from the survey would find it useful to have information on any kind of values or economic values for different land uses.

As a more general deficit, respondents from the survey formulated a need for practical methods that would help to communicate landscape capacities and services in a simple and comparable way that would allow for making weighing decisions in political and public decision-making processes more transparent.

Integration of ES into existing planning processes

Prior to our survey, the ES concept was unknown by the majority of respondents (56 %). Only about a quarter of participants stated that they already knew the concept, either from scientific literature (in five cases), interviews and workshops (three cases), or collaborations in research projects (in two cases).

Survey respondents as well as key informant interviewees perceived an integration of ES information as generally useful. Across the different application contexts, at least 80 % of respondents interpreted an integration of the ES concept as highly useful, or at least slightly useful (Fig. 4). Integration was perceived as particularly useful in the contexts of scenario analyses, compensation schemes and project-oriented planning. For example, several key informants proposed to integrate ES information in Environmental Impact Regulation (EIR, see Sect. “The context: Spatial and landscape planning in Germany”) or in project oriented planning, for example to assess and communicate the marginal differences in ES benefits and values of alternative project proposals.

An interesting finding was that the level of perceived usefulness of the ES concept in different application contexts varied depending upon the existence of prior knowledge of the ES concept among planners. Contrary to our expectations, planners with prior knowledge of the ES concept did not evaluate the usefulness of ES information as significantly more optimistic. In the application contexts ‘scenario analyses’ and ‘public education’, planners with prior knowledge were even more pessimistic than their colleagues who were unfamiliar with the ES concept.

The perceived advantages and disadvantages of using ES information in different decision contexts are contradicting, both in the surveys and the key informant interviews (Supplementary Material 2). As a potential advantage, one respondent expected that with the ES concept, “[…] abstract advantages and disadvantages become graphic and consequences of planning are tangible”. Another participant suggested that “the presentation of ecosystem services could potentially increase the acceptance of [nature conservation] measures”, while being doubtful of “whether this anthropocentric approach is suitable for environmental education.” Disadvantages were seen in that, as one respondent explained, “the approach opens up a playhouse of endless and fruitless discussions about competing approaches and the most important weighing decisions disappear from sight.“Similar concerns interpreted the ES approach as an “unclear and excessive”, “difficult to judge”, and that the requested “level of detail requires considerable data gathering”. A major hindrance as mentioned by a number of participants is that regulatory frameworks determine the processes and procedures and planning and that additional ES information is not (yet) required to be included legally.

Participants also suggested additional fields of application of ES information, including (economic) valuation of services as guidance and additional arguments for political decision-making. A particular benefit of ES information was seen in its capacity to provide quantitative estimates of the impacts of policy options on service provision, which would enhance comparability.

Formats for ES information communication

Semi-quantitative (ordinally scaled) evaluations are the conventional format used by landscape and spatial planners in Germany to communicate services of nature and landscape. In our survey, both planners with and without prior knowledge of the concept perceived this approach as easily comprehensible and particularly useful for discussions with political decision-makers. Planners without prior knowledge also appreciated the comparability of semi-quantitative information. This was perceived differently by some planners with prior knowledge of the ES concept, e.g. one respondent pointed out that “semi-quantitative approaches include intransparent prior weighing”, which requires, according to another respondent, “expert knowledge to assess semi-quantitative information”. A third respondent makes the point that integrating ES information in general would make an already complex planning approach even more intransparent for decision makers. Further, some respondents criticized that semi-quantitative descriptions provide only relatively weak arguments that could easily be ignored in weighing processes.

Concerning cardinally scaled ES assessments and evaluations, planners see similar advantages and disadvantages regardless of their degree of prior knowledge of the concept. A stated advantage of cardinal evaluations was that they would provide measurable and transparent descriptions of ES, considered as robust, and spatially explicit empirical evidence. As such, accounting approaches based on cardinally scales assessments would provide an opportunity to compare costs with outcomes. Disadvantages mentioned concerned acceptance of cardinally scales evaluation and accounting data as it would be even more difficult to understand than semi-quantitative assessments. Another respondent adds: “[…] there is the danger that planning uses numbers that appear to be accurate but indeed are not (pseudo-accuracy).”

Economic valuation was also perceived ambiguously. Advantages of economic valuation are seen in that everybody could relate to monetary terms and find them concise and striking. Further, economic values could be beneficial in initiating a discussion as well as in comparing and ranking alternatives. Disadvantages mentioned for economic values differ slightly between respondents with and without prior knowledge. Planners familiar with the ES concept stressed the problem that different economic valuation methods would lead to diverging results, thus limiting comparability across studies. A further challenge is that while potential damage costs are potentially very useful in the political realm, they still have high uncertainty margins (UBA - Federal Environmental Agency 2008) and depend on the calculation method chosen. The concerns of planners without prior knowledge remain more general. They again highlight the pseudo-accuracy, but also argue that monetary values would suggest some kind of commensurability that cannot readily be assumed, but which might nevertheless create a bias towards monetary aspects.

Discussion and conclusion

Although we did not aim at representativeness, the key informant interviews and the web-based survey have resulted in valuable insights concerning German regional and landscape planners’ general use of environmental information in weighing and decision-making, and their perceptions concerning the applicability of the ES concept in different planning fields. As discussed below, these insights could be helpful concerning efforts of mainstreaming ES in planning and in understanding the specific opportunities and challenges for different planning communities. However, the results need to be interpreted with some caution in relation to the relatively small number of completed surveys. While the turnout rate of filled-out surveys was very positive, it was challenging that only about half of the participants responded to the question relating to the usefulness of the ES concept and of different ES information types. However, we found the survey answers are well reflected in our key informant interviews as well as in the ongoing discussions in the field of landscape and regional planning in Germany (e.g. Hauck et al. 2013b). The issues and suggestions raised here might also be transferable to other countries with established land planning systems, especially within the European context, as the general problems of planning as to communicating objectives to decision-makers are similar (cf. Nadin and Stead 2008). In particular, many planning systems currently share the need to address pertaining implementation deficits while at the same time incorporate technical advances in analytical modeling and decision support systems (e.g. Faludi and Waterhout 2006; Huser et al. 2009) in their planning processes. Our survey asked spatial planners in a fairly tradition planning setting without many interactive or participatory elements in the final decision making process. These frame conditions may have influenced planners’ perceptions concerning the ES concept whose benefits arguably could be greatest in participatory and transdisciplinary planning and decision support systems (see e.g. Geertman and Stillwell 2004; Arciniegas and Janssen 2012).

Opportunities for integrating ES information

In general, landscape planners considered a narrower spectrum of ecosystem services than regional planners which corresponds to their assigned roles in the German planning system where regional planning should integrate and coordinate a broad range of different sectors. However, it also may suggest that if landscape planners put greater emphasis on multifunctionality (Galler et al. Under Rev) and provisioning and regulating ES in their planning proposals, they could potentially enhance, public acceptance and better relate to different stakeholder groups including e.g. water administration. This could help addressing their wish for ‘acceptance by local land users’ and ‘by the public’. This greater emphasis on the acceptability of planning proposals can be explained by two factors: firstly landscape planning in most German states does not become legally binding in itself but relies on the uptake of its objectives by regional planning or the environmental agencies as well as land users and citizens. Secondly, many of the landscape planning objectives represent restrictions both to local authorities who want to expand the built up area as well as to farmers or foresters aiming at maximizing revenue from land use. Whereas integration into other public planning is comparably easy, the implementation of restricting legal measures by the nature conservation administration or of voluntary measures by land users calls for a high persuasive power of the objective as well as for accompanying economic incentives. Such objectives include for example technical advice to farmers and advisory services relating to farm land, which is prone to soil erosion or compaction, the conservation of habitats which are locally or regionally valuable but not objects of mandatory regulation, or measure for enhancing the aesthetic and nature conservation quality of the landscape including settlements. Spatial planning—in contrast—becomes mandatory in itself and on the other hand represents not predominantly restricting environmental objectives but also economic and social interests. If the ES concept fulfills its promise to better illustrate the benefits of nature conservation and sustainable use for human well-being (e.g. Hauck et al. 2013b), an application of the concept could thus be of particular interest for landscape planners as a way to better identify synergies between economic and environmental interests and enhance public and decision-makers’ acceptance of their proposals. Vice versa, the findings also suggest that regional planners could be more open to adopt the concept due to their already existent experience in considering a broad spectrum of sectors.

Limitations for integrating ES information

While the specific ES application conditions vary across the different decision-making contexts, some common limitations and concerns of an integration of ES information could be extracted from the answers. Planners’ diverging perspectives concerning the opportunities and benefits of including ES information in different decision-making contexts suggest that a short-term integration of ES information in existing planning procedures is rather unlikely. Landscape and regional planners’ environmental information needs are almost entirely fulfilled by existing landscape plans. Many participants stressed that regional and landscape planning is already a very complex and tedious process that needs to comply with various regulations and to consider different interest groups. Adding another layer of complexity with an integration of ES assessments does not seem feasible in the current practice context. This suggest that the mainstreaming of ES information into formal, long-term, comprehensive planning processes needs to be requested and legitimized by regulatory frameworks provided by superior levels such as the national or EU level. However, planners’ concern would remain that an increased complexity could also limit the transparency and communicability of planning decisions and hence lower the acceptance by the broader public.

A major issue is the expected additional workload for data collection and assessment if new aspects of ES should be considered in addition to the environmental information already processed according to the formal planning system regulations. Taking into account that planners already face the problem that environmental information is often outdated, it seems unlikely that additional resources will become available in the future for conducting more complex ES assessment and valuation studies as part of the planning process.

In general, participants reemphasized that environmental information is only one of several aspects driving decision-making and they were skeptical that information on ES could significantly enhance receptiveness of decision-makers and stakeholders. Monetary valuation in this context was perceived as potentially beneficial but also dangerous as the valuations could also be contradicting to environmental objectives, in particular for biodiversity conservation. In view of these limited resources, two question should be raised: (i) How much does the generation of additional ES information cost and what are the technical potentials for reducing such costs e.g. by automated processing? (ii) What is the added value and what evidence do we have for the efficiency of supporting implementation by ES information?

Promising approaches for acquiring and communicating ES information

Scientific information in general indeed proved to be an important source of information for planners. However, this information was only rarely used in form of scientific publications as in professional journals, but much more frequently as “applied” scientific information as included in landscape plans, expert reports and opinions. This finding suggests that if ES information should be made useful, it needs to be integrated in such place-based recommendations. Interactive methods of information provision such as discussions during workshops and conferences might also be beneficial. Practical and easy-to-understand information materials could help in better illustrating how ecological elements, structures and processes within landscapes provide services, and the benefits and value that these services hold for human well-being. Another reason could be the often cited challenge that scientific publications in professional journals are only rarely accessible to planning practitioners.

The survey illustrated that habitats and species data are widely available and used as the primary source of information on nature and landscape. However, it needs to be kept in mind that while this data was often available, its accuracy and timeliness was questioned, highlighting the need for updates and regular monitoring. Furthermore, the German federal states use different habitat classification schemes which are very difficult to harmonize and thus form a barrier for the development of generalizable methods. Participants generally requested more information on cultural services—here, it should be tested in how far new methods for relatively easy assessments (e.g. Wood et al. 2013) can be implemented within conventional planning practice. Economic valuation was hardly missed, regardless if it was monetary or non-monetary.

Interestingly, databases also emerged as an information source regularly consulted by landscape and spatial planners. Further research should investigate how existing databases are currently used, and if and how additional ES information could be included as a way to make this knowledge available for planners. Furthermore, the importance of databases as an information source for planners should be kept in mind in the design and implementation of ES assessment processes as a way to make assessment results available in decision-support.

The relatively little prior knowledge of the ES concept shows that much capacity building is still required even within the planning community to convey better understanding of the ES concept and its implications for planning. The counterintuitive finding that better knowledge about the ES concept does not always lead to a more optimistic interpretation of the usefulness of ES information in planning leads us to suggest that, apart from the more top–down mainstreaming ES information in planning via laws and directives, additional efforts need to be made to develop approaches for an easier application and communication of the ES concept to practitioners and among practice communities from different sectors.

Since no consensus emerged concerning preferred formats (ordinal or semi-quantitative, cardinal or accounting, economic valuation) for communicating ES information in application contexts, we suggest using a combination of formats that compensate respective shortcomings and are specifically adapted to each application context. Semi-quantitative ES information is likely to be the easiest to integrate, as currently available environmental information is also often provided in this format. Cardinally scaled information, respective accounting, and economic values of ES could be a beneficial, additional argument for the protection and sustainable use of natural resources. In particular, cardinally scaled estimates would provide an opportunity to better compare differences of different scenarios and changes over time. Economic valuation could serve as a hook into political and public debates. Both quantitative estimates and economic values of ES could provide an innovative means to better compare the impacts of alternative policy options, e.g. in SEA, EIA or EIR. This would allow planners, decision-makers and the public to better understand the trade-offs among the different alternatives instead of only comparing different scenarios in terms of land use and impact maps without considering summative impacts, as in conventional planning. Due to greater transparency and eased communication of decisions, respondents also found the ES concept helpful for communication with the public.

Recommendations

In order to better link practitioners’ needs and interests in ES information with scientists capacities to provide such information, transdisciplinary case studies (Jahn et al. 2012; Lang et al. 2012, see Albert et al. 2012b for an example) of ES application in real-world planning and decision-making contexts should be conducted. The effects of ES information on and its usefulness for subsequent decision-making should be critically evaluated (Nassauer and Opdam 2008; Beunen and Opdam 2011). Practical guidelines for operationalizing the ES concept in planning practice, and the use of tools such as InVest (http://www.naturalcapitalproject.org/InVEST.html) could be a possible option for enhancing applicability and understanding. Furthermore, a sensitive management of the science-policy interface as well as participatory approaches to co-generate ES assessment methods among planners, scientists, stakeholders and decision makers should be employed in order to enhance mutual understanding, social learning, and the likelihood of an uptake of ES information in planning and decision-making (e.g. Cork and Proctor 2005; Huitema et al. 2010).

From our findings, and particularly from the constraints perceived by the planers, we suggest that ES research more explicitly take into account the interests, decision-contexts, and requirements of potential users if it intends to provide relevant information for decision-support. An analysis of the required information, as reported in this paper, can thereby be a first step. We further recommend to consider the following aspects in future efforts to provide useful ES information to planning and decision-making at the regional scale: (i) To clarify the addressees for the ES information, (ii) to explore the decision making context at planning or policy stage in which the research results are supposed to be used, (iii) to critically evaluate if the ES information is needed in addition to the already existing information—for example in highlighting previously unconsidered issues—in order to justify the additional resources required, (iv) to make sure that the ES information is presented in a format that complies with existing data, planning instruments and understanding, without overstretching the capacities and resources of planners/planning administration, (v) to ensure that the methods used to provide ES information are easy to use and at the same time sufficiently robust and transparent in order to serve as the basis for land use decision-making.

References

Albert C, von Haaren C, Galler C (2012a) Ökosystemdienstleistungen: alter Wein in neuen Schläuchen oder ein Impuls für die Landschaftsplanung? Naturschutz Landschaftsplanung 44:142–148

Albert C, Zimmermann T, Knieling J, von Haaren C (2012b) Social learning can benefit decision-making in landscape planning: gartow case study on climate change adaptation, Elbe valley biosphere reserve. Landscape Urban Planning 105:347–360

Arciniegas G, Janssen R (2012) Spatial decision support for collaborative land use planning workshops. Landscape Urban Planning 107:332–342

ARL (2005) Handwörterbuch der Raumordnung. Akad. für Raumforschung und Landesplanung - ARL, Hannover

ARL (2011) Grundriss der Raumordnung und Raumentwicklung. Verlag der ARL, Hannover

Bastian O, Haase D, Grunewald K (2012) Ecosystem properties, potentials and services: the EPPS conceptual framework and an urban application example. Ecol Ind 21:7–16

Bateman IJ, Harwood AR, Mace GM, Watson RT, Abson DJ, Andrews B, Binner A, Crowe A, Day, BH, Dugdale S, Fezzi C, Foden J, Hadley D, Haines-Young R, Hulme M, Kontoleon A, Lovett AA, Munday P, Pascual U, Paterson J, Perino G, Sen A, Siriwardena G, van Soest D, Termansen M (2013) Bringing ecosystem services into economic decision-making: land use in the United Kingdom. Science 341(6141):45-50

Beunen R, Opdam P (2011) When landscape planning becomes landscape governance, what happens to the science? Landscape Urban Planning 100:324–326

Brouwer R, Brander L, Kuik O, Papyrakis E, Bateman I (2013) A synthesis of approaches to assess and value ecosystem services in the EU in the context of TEEB final report

Burkhard B, Petrosillo I, Costanza R (2010) Ecosystem services: bridging ecology, economy and social sciences. Ecol Complex 7:257–259

Burkhard B, de Groot R, Costanza R, Seppelt R, Joergensen SE, Potschin M (2012) Solutions for sustaining natural capital and ecosystem services. Ecol Ind 21:1–6

Cork SJ, Proctor W (2005) Implementing a process for integration research: ecosystem services project. Aust J Res Pract 1:M6

Cowling RM, Egoh B, Knight AT, O’Farrell PJ, Reyers B, Rouget M, Roux DJ, Welz A, Wilhelm-Rechman A (2008) An operational model for mainstreaming ecosystem services for implementation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:9483

Daily GC, Polasky S, Goldstein J, Kareiva PM, Mooney HA, Pejchar L, Ricketts TH, Salzman J, Shallenberger R (2009) Ecosystem services in decision making: time to deliver. Front Ecol Environ 7:21–28

de Groot RS, Alkemade R, Braat L, Hein L, Willemen L (2010) Challenges in integrating the concept of ecosystem services and values in landscape planning, management and decision making. Ecol Complex 7:260–272

European Commission (2011) Our life insurance, our natural capital: an EU biodiversity strategy to 2020. COM(2011) 244

Faludi A, Waterhout B (2006) Introducing evidence-based planning. disP – Planning Rev 42:4–13

Fisher TB (2007) Theory and practice of strategic environmental assessment: towards a more systematic approach. Earthscan, London

Galler C, Von Haaren C, Albert C (Under Rev) Enhancing landscape management effectiveness and efficiency by optimizing multifunctional effects of environmental measures: case study results and recommendations for Designing Agri-Environmental Programs. J Environ Manage

Geertman S, Stillwell J (2004) Planning support systems: an inventory of current practice. Comput Environ Urban Syst 28:291–310

Geneletti D (2013) Ecosystem services in environmental impact assessment and strategic environmental assessment. Environ Impact Assess Rev 40:1–2

Haase G (1978) Zur Ableitung und Kennzeichnung von Naturraumpotentialen. Petermans Geogr Mitteilungen 112:113–125

Hauck J, Görg C, Varjopuro R, Ratamäki O, Maes J, Wittmer H, Jax K (2013a) Maps have an air of authority: potential benefits and challenges of ecosystem service maps at different levels of decision making. Ecosyst Serv 4:25–32

Hauck J, Schweppe-Kraft B, Albert C, Görg C, Jax K, Jensen R, Fürst C, Maes J, Ring I, Hönigová I, Burkhard B, Mehring M, Tiefenbach M, Grunewald K, Schwarzer M, Meurer J, Sommerhäuser M, Priess JA, Schmidt J, Grêt-Regamey A (2013b) The promise of the ecosystem services concept for planning and decision-making. GAIA 22:232–236

Hay I (ed) (2005) Qualitative research methods in human geography. Oxford University Press, New York

Helming K, Diehl K, Geneletti D, Wiggering H (2013) Mainstreaming ecosystem services in European policy impact assessment. Environ Impact Assess Rev 40:82–87

Huitema D, Cornelisse C, Ottow B (2010) Is the jury still out? Toward greater insight in policy learning in participatory decision processes—the case of Dutch citizens’ juries on water management in the Rhine Basin. Ecol Soc 15:16

Huser B, Rutledge DT, Van Delden H, Wedderburn ME, Cameron M, Elliott S, Fenton T, Hurkens J, Mcbride G, Mcdonald G, O’Connor M, Phyn D, Poot J, Price R, Small B, Tait A, Vanhout R, Woods RA (2009) Creating futures: towards an integrated spatial decision support system for local government in New Zealand. In: Anderssen RS, Braddock RD and Newham LTH (eds) 18th IMACS world congress – MODSIM09 international congress on modelling and simulation, Cairns, Australia, ISBN: 978-0-9758400-7-8

Jahn T, Bergmann M, Keil F (2012) Transdisciplinarity: between mainstreaming and marginalization. Ecol Econ 79:1–10

Kates RW, Parris TM (2003) Long-term trends and a sustainability transition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:8062–8067

Koschke L, Fürst C, Frank S, Makeschin F (2012) A multi-criteria approach for an integrated land-cover-based assessment of ecosystem services provision to support landscape planning. Ecol Ind 21:54–66

Lang D, Wiek A, Bergmann M, Stauffacher M, Martens P, Moll P, Swilling M, Thomas C (2012) Transdisciplinary research in sustainability science: practice, principles, and challenges. Sustain Sci 7:25–43

Nadin V, Stead D (2008) European spatial planning systems, social models and learning. disP Plan Rev 172:35–47

Nassauer JI, Opdam P (2008) Design in science: extending the landscape ecology paradigm. Landscape Ecol 23:633–644

Neef E (1966) Zur Frage des gebietswirtschaftlichen potentials. Forschungen Fortschritte 40:65–70

Opdam P (2010) Learning science from practice. Landscape Ecol 25:821–823

Opdam P, Nassauer JI, Wang Z, Albert C, Bentrup G, Castella J-C, McAlpine C, Liu J, Sheppard S, Swaffield S (2013) Strengthening the science-policy interface at the local scale. Landscape Ecol 28:1439–1445

Plieninger T, Bieling C, Gerdes H, Ohnesorge B, Schaich H, Schleyer C, Trommler K, Wolff F (2010) Ökosystemleistungen in Kulturlandschaften - Konzept und Anwendung am Beispiel der Biosphärenreservate Oberlausitz und Schwäbische Alb. Natur Landschaft 85:187–192

Primmer E, Furman E (2012) Operationalising ecosystem service approaches for governance: do measuring, mapping and valuing integrate sector-specific knowledge systems? Ecosyst Serv 1:85–92

Scolozzi R, Morri E, Santolini R (2012) Delphi-based change assessment in ecosystem service values to support strategic spatial planning in Italian landscapes. Ecol Ind 21:134–144

Selman P (2012) Sustainable landscape planning: the reconnection agenda. Abington, Routledge

TEEB 2010. The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity: Ecological and Economic Foundations, Edited by Pushpam Kumar, London and Washington, D.C., Earthscan

Termorshuizen J, Opdam P (2009) Landscape services as a bridge between landscape ecology and sustainable development. Landscape Ecol 24:1037–1052

UBA - Federal Environmental Agency (2008) Economic valuation of environmental damage: methodological convention for estimates of environmental externalities. Federal Environmental Agency, Dessau-Roßlau

von Haaren C (ed) (2004) Landschaftsplanung. Eugen Ulmer, Stuttgart

von Haaren C, Albert C (2011) Integrating ecosystem services and environmental planning: limitations and synergies. Int J Biodiv Sci Ecosyst Serv Manage 7:150–167

von Haaren C, Saathoff W, Galler C (2011) Integrating climate protection and mitigation functions with other landscape functions in rural areas: a landscape planning approach. J Environ Plan Manage 55:59–76

Wiek A, Binder C, Scholz RW (2006) Functions of scenarios in transition processes. Futures 38:740–766

Wittmer H, Gundimedia H (eds) (2012) The economics of ecosystems and biodiversity in local and regional policy and management. Routledge, London

Wood SA, Guerry AD, Silver JM, Lacayo M (2013) Using social media to quantify nature-based tourism and recreation. Sci Reports 3:2976

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our interviewees and survey respondents for their time and willingness to take part in our study and to provide their insights and expertise. Furthermore, we would like to thank two anonymous reviewers who provided very helpful guidance and advice for the revision. We are grateful for the support of Bea Achtermann, Johannes Hermes, Frauke Lehrke and Felix Neuendorf who helped to set up the internet survey and to evaluate the results. And we thank Frank Schaarschmidt for analyzing our survey data with different statistical methods. Funding for the study was provided through a research grant for the project “QUANTIY-Quantifying Ecosystem Services as Decision Support in Landscape Planning” by Leibniz Universität Hannover.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Albert, C., Hauck, J., Buhr, N. et al. What ecosystem services information do users want? Investigating interests and requirements among landscape and regional planners in Germany. Landscape Ecol 29, 1301–1313 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-014-9990-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-014-9990-5