Abstract

Following activation by G-protein-coupled receptor agonists, protein kinase C (PKC) modulates cardiac myocyte function by phosphorylation of intracellular targets including myofilament proteins cardiac troponin I (cTnI) and cardiac myosin binding protein C (cMyBP-C). Since PKC phosphorylation has been shown to decrease myofibril ATPase activity, we hypothesized that PKC phosphorylation of cTnI and cMyBP-C will lower myocyte power output and, in addition, attenuate the elevation in power in response to protein kinase A (PKA)-mediated phosphorylation. We compared isometric force and power generating capacity of rat skinned cardiac myocytes before and after treatment with the catalytic subunit of PKC. PKC increased phosphorylation levels of cMyBP-C and cTnI and decreased both maximal Ca2+ activated force and Ca2+ sensitivity of force. Moreover, during submaximal Ca2+ activations PKC decreased power output by 62 %, which arose from both the fall in force and slower loaded shortening velocities since depressed power persisted even when force levels were matched before and after PKC. In addition, PKC blunted the phosphorylation of cTnI by PKA, reduced PKA-induced spontaneous oscillatory contractions, and diminished PKA-mediated elevations in myocyte power. To test whether altered thin filament function plays an essential role in these contractile changes we investigated the effects of chronic cTnI pseudo-phosphorylation on myofilament function using myocyte preparations from transgenic animals in which either only PKA phosphorylation sites (Ser-23/Ser-24) (PP) or both PKA and PKC phosphorylation sites (Ser-23/Ser-24/Ser-43/Ser-45/T-144) (All-P) were replaced with aspartic acid. Cardiac myocytes from All-P transgenic mice exhibited reductions in maximal force, Ca2+ sensitivity of force, and power. Similarly diminished power generating capacity was observed in hearts from All-P mice as determined by in situ pressure–volume measurements. These results imply that PKC-mediated phosphorylation of cTnI plays a dominant role in depressing contractility, and, thus, increased PKC isozyme activity may contribute to maladaptive behavior exhibited during the progression to heart failure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The complexities of the human heart failure syndrome obscure clear discernment between primary pathological effects and secondary compensatory events. While several studies have confirmed up-regulation of PKCα, PKCβ, and PKCε expression and/or activity in human heart failure (Bowling et al. 1999; Noguchi et al. 2004; Strasser et al.1996), it remains unknown whether this plays a causative or compensatory role, or both. Generation of transgenic protein kinase C (PKC) isoform overexpression and knock-out mouse models suggest PKC can yield either pathologic (Gu and Bishop 1994; Wakasaki et al. 1997; Bowman et al. 1997; Hahn et al. 2003; Braz et al. 2004; Goldspink et al. 2004; Belin et al. 2007) or compensatory (Qui et al. 1998; Mochly-Rosen et al. 2000; Takeishi et al. 2000; Inagaki et al. 2003; Gray et al. 2004) events depending upon isoform and its signal intensity and duration. Another confounding factor in determining PKC’s role in cardiomyopathy is its ubiquitous functions. PKC influences a number of cellular processes including regulation of pH (Terzic et al. 1992), transcriptional regulation (Nishizuka 1995), myocyte hypertrophy/remodeling (Vlahos et al. 2003; Dorn and Force 2005), Ca2+ fluxes (Endoh and Blinks 1988; Zhang et al. 1997; Huang et al. 2001; Aiello and Cingolani 2001), and myofilament contraction (Belin et al. 2007; Noland and Kuo 1991; Pi et al. 2003; Van der Velden et al. 2006). Seemingly, a convergent end-point for PKC’s signaling networks is the contractile function of the myofilaments and this outcome measure allows potential distinction between pathological and compensatory events. For instance, if PKC induces an increased Ca2+ sensitivity of myofilament force (Terzic et al. 1992; Pi et al. 2003; Puceat et al. 1990; Noland and Kuo 1993), which, in turn, causes faster loaded shortening velocity and power, this would implicate a positive inotropic mechanism (Huang et al. 2001; Huang et al. 1997; Pi and Walker 2000) to perhaps compensate for other cellular defects. Conversely, if PKC decreased Ca2+-activated force/ATPase (Belin et al. 2007; Noland and Kuo 1991; Noland et al. 1995; Jideama et al. 1996; Sumandea et al. 2003), loaded shortening, and power, this would implicate a sub-cellular pathological mechanism since ventricular function is ultimately dictated by force, rate of force production, and work capacity of the myofilaments. One purpose of the study was to directly investigate how PKC affects force, loaded shortening, and power generation of cardiac myocyte preparations.

A second objective was to examine the interplay between PKC and protein kinase A (PKA)-mediated phosphorylation on myofilament function. There is some evidence that PKC dominates PKA effects in heart function. For instance, faster−dP/dt was observed in transgenic mice containing proteins cardiac troponin I (cTnI) pseudo-phosphorylation at PKA sites and this effect was prevented by pseudo-phosphorylation at PKC sites on cTnI (Sakthivel et al. 2005). In addition, minimal incorporation (i.e., ~7 %) of PKC pseudo-phosphorylated cTnI into cardiac myofilaments yielded lower developed myofilament force and left ventricular pressure (Kirk et al. 2009). Here we hypothesized that PKC-mediated phosphorylation will attenuate the elevation in power known to occur in myofilaments due to PKA-mediated phosphorylation. Additionally, we tested whether altered thin filament function plays an essential role in these posited contractile changes by use of transgenic animals that expressed cTnI containing pseudo-phosphorylation at both PKA and PKC sites (Ser-23/Ser-24/Ser-43/Ser-45/T-144; i.e., All-P mice). For many of the experiments, myofilament functional measurements were performed using rodent skinned cardiac myocyte preparations. These preparations yield mechanical records free of confounding effects due to extracellular viscoelastic structures and, thus, allow direct study of the mechanisms that control myofibrillar force and power generation.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals

Male Sprague–Dawley rats (~6 weeks old) were obtained from Harlan (Madison, WI, USA) were housed in groups of two and provided food and water ad libitum. Transgenic mice expressing wild type cTnI (WT), or aspartic acid replacement of phosphorylation sites Ser23/Ser24 (targets of PKA and/or PKC) alone (PP) or in combination with Ser43/Ser45 and Thr144 (targeted by PKC) (All-P) to mimic a constant state of phosphorylation were bred in-house and transgenesis was validated by RT-PCR as previously described (Sakthivel et al. 2005). All procedures involving animal use were performed according to protocols that were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Missouri and/or the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Apparatus and mechanical experiments

Cardiac myocyte preparations were obtained by mechanical disruption of hearts from male 2- to 3-month-old Sprague–Dawley rats or transgenic mice as described previously (McDonald 2000). Rodents were placed in an air-tight chamber and anaesthetized by inhalation of isoflurane (20 % (v/v) in olive oil) and their hearts were quickly removed and placed in ice-cold relaxing solution. The atria and right ventricles were removed and the left ventricles were cut into 2–3 mm pieces and further disrupted for 5–10 s using a Waring blender. The resulting suspension of cells and cell fragments were centrifuged for 105 s at 165 g. The myocytes were subsequently skinned by suspending the pellet for 4 min in 0.3 % ultrapure Triton X-100 (Pierce Biotechnology, Inc, Rockford, IL, USA) in relaxing solution. The pellet was washed twice with cold relaxing solution and the skinned cells were then re-suspended in 10–20 mL of relaxing solution and kept on ice during the day of the experiment. The experimental apparatus for physiological measurements on myocyte preparations was similar to one previously described in detail (McDonald 2000). Myocyte preparations were attached between a force transducer and torque motor by placing the ends of the myocyte preparation into stainless steel troughs (25 gauge). The ends of the myocyte preparations were secured by overlaying a 0.5 mm length of 3–0 monofilament nylon suture (Ethicon, Inc) onto each end of the myocyte, and then tying the suture into the troughs with two loops of 10–0 monofilament (Ethicon, Inc). The attachment procedure was performed under a stereomicroscope (~100× magnification) using finely shaped forceps. Prior to mechanical measurements, the experimental apparatus was mounted on the stage of an inverted microscope (model IX-70, Olympus Instrument Co., Japan), which was placed upon a pneumatic vibration isolation table having a cut-off frequency of ~1 Hz. Mechanical measurements were performed using a capacitance-gauge transducer (Model 403, sensitivity of 20 mV mg−1 (plus a 10× amplifier) and resonant frequency of 600 Hz; Aurora Scientific, Inc, Aurora ON, Canada).

Compositions of relaxing and activating solutions used in mechanical measurements were as follows: 7 mM EGTA, 1 mM free Mg2+, 20 mM imidazole, 4 mM MgATP, 14.5 mM creatine phosphate, pH 7.0, various Ca2+ concentrations between 10−9 M (relaxing solution) and 10−4.5 M (maximal Ca2+ activating solution), and sufficient KCl to adjust ionic strength to 180 mM. The final concentrations of each metal, ligand, and metal–ligand complex at 13 °C were determined with the computer program of (Fabiato 1988). Preceding Ca2+ activations, myocyte preparations were immersed for 30 s in a solution of reduced Ca2+-EGTA buffering capacity, which was identical to normal relaxing solution except that EGTA was reduced to 0.5 mM. This protocol resulted in more rapid development of steady state force during subsequent activation and helped preserve the striation pattern during activation. Relaxing solution in which the ventricles were mechanically disrupted and myocytes resuspended contained 2 mM EGTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 4 mM ATP, 10 mM imidazole, and 100 mM KCl at pH 7.0 with the addition of a protease inhibitor cocktail (Set I Calbiochem, San Diego, CA).

Force–velocity and power-load measurements

All mechanical measurements were made at 13 ± 1 °C. The protocol for force–velocity and power-load measurements has been previously described (McDonald 2000). Force–velocity and power-load measurements were made on each myocyte before and after treatment with the catalytic subunit of PKC (Sigma 0.5 μg/mL). First, the myocyte was transferred into maximal Ca2+ activating solution to obtain maximum force. The myocyte was then transferred in a near half-maximal [Ca2+] activating solution, and once steady-state force was attained, a series of force clamps was performed to determine isotonic shortening velocities. Using a servo system, force was maintained constant for a designated period of time (150–250 ms) while the length change was continuously monitored. After the force clamp, the myocyte preparation was slackened to reduce force to near zero to allow estimation of the relative load sustained during isotonic shortening; the myocyte was subsequently re-extended to its initial length. After the first series of force clamps, the myocyte was treated with the catalytic subunit of PKC for 45 min and loaded shortening velocities were again measured (Table 1). In a separate group of myocytes force–velocity relationships were also obtained during half-maximal Ca2+ activations before and after PKA treatment (Sigma, 0.125 U μl−1) following PKC (Table 1).

SDS-PAGE and autoradiography

To examine myofibrillar substrates of PKC, myofibrillar samples from rats were incubated with the catalytic subunit of PKC or PKC then PKA in the presence of radiolabeled ATP, separated by SDS-PAGE, and visualized by autoradiography. Briefly, 10 μg of skinned cardiac myocytes were incubated with the catalytic subunit of PKC (0.5 μg/mL) and 50 μCi [γ-32P]-ATP for 60 min. A second set of skinned cardiac myocytes were treated with the catalytic subunit of PKC for 60 min in the absence of radiolabelled ATP followed by treatment with the catalytic subunit of PKA (2.5 U/μl) and 50 μCi [γ-32P]-ATP for 60 min. The reaction was stopped by the addition of electrophoresis sample buffer and heating at 95 °C for 3 min. The samples were then separated by SDS-PAGE (12 % acrylamide), silver stained, dried, and subsequently exposed to x-ray film for ~24 h at −70 °C.

In situ pressure–volume analysis

Experiments were carried out according to guidelines instituted by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Illinois at Chicago (ACC# 05-240). The in situ pressure–volume methods were as previously described (Scruggs et al. 2009). Male and female mice 13 weeks of age were sedated with Etomidate (8 μg/g BW, i.p.), intubated and ventilated (100 % O2/1.5 % isoflurane). A 1.4 French pressure–volume catheter (Millar Instruments, Houston, TX) was inserted retrograde into the left ventricle (LV) across the aortic valve, and steady-state hemodynamics were recorded (Chart5 ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO). A midline incision was made to locate the supradiaphragmatic inferior vena cava (IVC). Venous return to the heart was briefly occluded to generate a series of descending loops for deriving the end-systolic pressure–volume relationship. Pressure–volume traces were analyzed using PVAN 2.9 software (Millar Instruments). A series of loops were selected during steady-state, and hemodynamic parameters were averaged. For measures of contractility, loops from an IVC occlusion were selected to calculate maximal ventricular power output. Algorithms used to calculate these parameters were those inherent to PVAN 2.9.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise indicated. To determine differences between groups either one-way repeated measure or ANOVA tests were used. A Student-Neuman-Keuls test was performed as a post hoc test. In all cases, p < 0.05 was accepted as significant difference between populations.

Results

Rat cardiac myocyte preparations were 106 ± 17 μm in length and 22 ± 5 μm in width (n = 9). Sarcomere length was set at ~2.30 μm, which yielded 0.27 ± 0.08 μN passive force and 11 ± 2 μN (or 44 ± 9 kN/m2) maximal Ca2+ activated force. PKC decreased maximal Ca2+ activated force (force after PKC = 10 ± 2 μN) and force during submaximal Ca2+ activations (force before PKC = 6.0 ± 0.8 μN; force after PKC = 3.4 ± 0.3 μN) (Fig. 1). Moreover, PKC decreased absolute power output by 62 % (power before PKC = 72 ± 17 pW vs. power after PKC = 27 ± 7 pW (n = 6)), which arose from both the fall in force and slower loaded shortening velocities (Fig. 1). Slower loaded shortening was observed at all relative loads after normalization of isometric force (Fig. 1, left panel). Since slower loaded shortening even at relative force levels may have arisen simply due to lower force levels (McDonald 2000) additional experiments examined force–velocity and power-load curves when force was matched before and after PKC; force was matched by simply increasing activator [Ca2+] after PKC treatment to correct for the decrease in Ca2+ sensitivity of force. Force was 5.4 ± 0.68 μN before PKC and 4.9 ± 0.5 μN (n = 4, (N.S.)) after PKC (Fig. 2). Here again, PKC caused slower loaded shortening and yielded reductions in power output (power before PKC = 60 ± 28 pW; power after PKC = 46 ± 23 pW; p < 0.04) (Fig. 2).

a. Absolute force–velocity (top) and power-load curves (bottom) from a cardiac myocyte preparation (date: 08/30/06) activated at a submaximal [Ca2+] (pCa 5.9) before (closed circles) or after treatment with the catalytic subunit of PKC (open circles). b. Normalized force–velocity and power-load curves from myocytes activated at submaximal Ca2+ levels before or after treatment with the catalytic subunit of PKC. Inset shows myocyte length (top) and force (bottom) traces during load clamps before PKC (black) and after PKC (grey). Bar plots show mean force and power output values before and after PKC. (mean ± SD, N = 7, *p < 0.05)

Since β-adrenergic stimulation and its downstream signaling molecules (including PKA) are known to increase ventricular contractility and augment power generating capacity of permeabilized cardiac myocytes (Herron et al. 2001; Hanft and McDonald 2009), we tested whether PKA could rescue depressed myocyte power induced by PKC. When rat myocyte preparations were treated with PKA after PKC treatment, power generating capacity remained depressed (Fig. 3), implicating PKC-mediated phosphorylation plays a dominate role in contractility. Consistent with this, an autoradiogram showed that PKC attenuated PKA-mediated phosphorylation of cMyBP-C and cTnI (Fig. 3b). This appears to arise from effects beyond simple competition for the same sites on cTnI since the sum of PKC alone and PKA after PKC signals were considerably less than the phosphate incorporation by PKA alone. On the other hand, for cMyBP-C, PKC alone plus PKC then PKA signals nearly equaled PKA alone, consistent with the idea of considerable overlap between PKC and PKA cMyBP-C amino acid phosphorylation sites (Venema and Kuo 1993). Interestingly, PKC also markedly reduced PKA-induced spontaneous oscillatory contractions (SPOCs) (Fig. 4). Sarcomere oscillation amplitudes were 2–4 times greater in PKA treated myocytes compared to myocytes treated with PKC prior to PKA (Fig. 4).

a. Absolute force–velocity and power-load curves from a myocyte preparation (date: 12/07/06) before PKC, after PKC, and then PKA in the presence of PKC during submaximal Ca2+ activations. PKC decreased myocyte force and power generating capacity. Power output remained depressed even after PKA, implicating PKC effects predominates over PKA on myocyte power generating capacity. Bar plots show mean ± SD force and power output values before PKC, after PKC, and after PKC then PKA (*p < 0.05 versus before PKC, § p < 0.05 versus after PKC). b. Autoradiogram of 1 μg permeabilized cardiac myocytes incubated for 1 h with the catalytic subunits of PKC (0.5 μg/mL) in the presence of 12.5 μCi [32P]-ATP (lane 1), PKA (5 μg/mL) in the presence of 12.5 μCi [32P]-ATP (lane 2), and PKC in the absence of radiolabelled ATP followed by PKA (lane 3) in the presence of 12.5 μCi [32P]-ATP. Consistent with the effects on power output, PKC attenuated the PKA-mediated phosphorylation of MyBP-C and cTnI

To address whether cTnI is the molecular sensor for the functional dominance of PKC effects, we utilized transgenic mouse models expressing modified cTnI molecules. Transgenic mice expressed (i) wild type cTnI (WT), (ii) aspartic acid replacement of phosphorylation sites Ser23/Ser24 (targeted primarily by PKA) (PP), and (iii) aspartic acid replacement of Ser23/Ser24 in combination with Ser43/Ser45 and Thr144 (targeted by PKC) (All-P). Cardiac myocyte preparations from these hearts were 123 ± 29 μm in length, 20 ± 4 μm in width (n = 21) and had a resting sarcomere length of ~2.30 μm. There were no differences in these parameters between groups. Consistent with the idea that PKC-mediated phosphorylation of cTnI has dominating effects on myocyte function, myocyte preparations from All-P mice had significantly reduced maximal Ca2+ activated force and lower power output (during half-maximal Ca2+ activations) compared to myocyte preparations from WT and PP (Fig. 5). Maximal Ca2+ activated force was 48 ± 18, 52 ± 13, 26 ± 14 kN/m2 for WT, PP, All-P groups, respectively. Peak power output was 3.38 ± 1.94, 4.00 ± 1.51, 1.31 ± 0.76 μW/mg for WT, PP, All-P, respectively. The peak power output results translated from skinned cardiac myocytes to mouse hearts, whereby ventricular power was significantly reduced in All-P mouse hearts compared to WT and PP as assessed by in situ pressure–volume analysis (Fig. 6).

a. Representative pressure and volume tracings from WT, PP, All-P mice using in situ pressure–volume analysis. b. The maximum rate of heart contraction (+dP/dtmax) and relaxation (−dP/dtmin) were measured and All-P mice had reduced maximal rate of contraction with no change in relaxation parameters (*p < 0.05 verusu NTG; § p < 0.05 versus PP). c. Ventricular power output was depressed in All-P transgenic mouse hearts compared to WT and PP mouse hearts. (*p < 0.05 versus NTG; § p < 0.05 versus PP). All plots mean ± SD (n = 3–5)

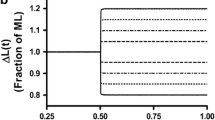

Since we previously observed PKA-mediated increase in power in rat cardiac myocytes (Herron et al. 2001; Hanft and McDonald 2009), the PP mice provided an opportunity to address if phosphorylation of cMyBP-C is necessary to augment power output. Maximal power generating capacity was not significantly different between myocyte preparations from WT and PP mice. (Peak normalized power output was 0.139 ± 0.034 P/Po*ML/s for WT compared to 0.147 ± 0.028 P/Po*ML/s for PP). However, when PP myocytes were treated with PKA, power generating capacity increased to values greater than before PKA (Peak normalized power output was 0.169 ± 0.034 P/Po*ML/s after PKA, n = 8). Interestingly, the PKA-mediated increase in power output was especially prominent at high loads (see Fig. 7). For instance, when loaded shortening values were pooled at all loads greater than 50 %, velocity was 0.125 ± 0.092 ML/s (n = 56) before PKA and 0.159 ± 0.098 ML/s (n = 68). These results implicate phosphorylation of cMyBP-C is necessary for manifestation of the PKA-mediated increase in myocyte power generating capacity.

PKA treatment increased power output (especially at loads greater than 50 %) in cardiac myocyte preparations from transgenic mouse hearts harboring pseudo-phosphorylated cTnI, which mimics PKA phosphorylation at serines 23/24. Bar plots show mean ± SD power output values before PKA and after PKA (n = 8, *p < 0.05 versus before PKA)

Discussion

The main findings of this study were (1) PKC-mediated phosphorylation of cTnI and cMyBP-C decreased (i) maximal Ca2+- activated force, (ii) Ca2+- sensitivity of force, and (iii) power generating capacity of permeabilized cardiac myocytes, (2) PKC-mediated phosphorylation prevented PKA-mediated augmentation of cTnI phosphorylation and myocyte power output, and (3) these PKC effects on myocyte function are mediated, in large part, by charged amino acids within cTnI.

Despite considerable investigation, the cellular role PKC plays in the progression of heart failure remains unclear. While a number of studies indicate increased PKC activity leads to maladaptive remodeling and dilated cardiomyopathy, other studies implicate a more compensatory or cardioprotective role for PKC (for reviews see (Vlahos et al. 2003; Dorn and Force 2005). These varied (and seemingly contradictory) results likely arise, at least in part, from PKC isoform specific effects and varied duration and intensity of its signal amplification. Our finding that PKC decreased myocyte power generation implies, at least on the face of it, a maladaptive functional effect that may ultimately compromise pump function. However, it is reasonable the decrease in myofibrillar force, Ca2+- sensitivity of force, and power could be compensatory as a means to conserve energy and improve contractile efficiency (work/ATPase) (as suggested by (Pi et al. 2003)), especially in a weakened heart. Under acute stress, however, elevated PKC-mediated phosphorylation may limit cardiac reserve. This could be a primary cause of, at minimum, acute pump failure, which is defined by ventricular output supply being unable to meet peripheral demands. This mechanistic explanation for pump failure is underscored by the finding that PKC attenuated the PKA response on myofibrillar function, signifying PKC has a dominant functional role at the myofilaments, which likely translates to ventricular function and is supported by this study and those of others (Sakthivel et al. 2005; Kirk et al. 2009; Bilchick et al. 2007).

We next sought to define which myofibrillar molecule mediates reduced power in response to PKC. We tested the idea that cTnI phosphorylation is sufficient to depress myofibrillar power by use of (All-P) transgenic animals that expressed cTnI containing pseudo-phosphorylation at conventional PKC sites (Ser-43/Ser-45/T-144) as well as at PKA sites (Ser-22/Ser-23) since PKC is known to cross-phosphorylate these sites (Pi et al. 2003; Van der Velden et al. 2006). Interestingly, All-P mouse myocytes mimicked the effects observed by PKC treatment of rat myocytes. These myocyte preparations exhibited depressed maximal Ca2+ activated force, reduced Ca2+-sensitivity of force, and decreased power generating capacity. These results suggest PKC-mediated phosphorylation of cTnI is sufficient to depress myofibrillar function and cTnI is the molecular sensor that manifests many of PKC-mediated myofibrillar effects. This is not overly surprising as there are distinct PKC sites on cTnI whereas the phosphorylatable residues on cMyBP-C largely overlap for both PKC and PKA (Venema and Kuo 1993). It is possible that compensatory changes occurred in the cTnI-AllP mice such as combinatorial post-translation modifications interacting in a complex manner to reduce permeabilized myocyte power. In addition, this study did not test whether other PKC myofibrillar substrates such as cardiac troponin T (cTnT) (Noland and Kuo 1993; Jideama et al. 1996; Sumandea et al. 2003), myosin regulatory light chain (RLC) (Goldspink et al. 2004; Pi et al. 2003), and/or titin (Hidalgo et al. 2009) modify myocyte power. However, the autoradiography studies (Fig. 3) suggest PKC sites on cTnT and RLC are either not phosphorylated by the catalytic subunit of PKC or have high baseline phosphorylation in our permeabilized cardiac myocyte preparations. In either event, PKC-mediated phosphorylation of cMyBP-C and/or cTnI (which are the only two proteins that show measurable phosphate incorporation (Fig. 3) yielded reduced cardiac myocyte power generation.

Even though results from this study support a dominant role of PKC-mediated cTnI phosphorylation on myofilament functional properties, the question remains whether PKC phosphorylation of cTnI actually occurs in vivo and if it increases during the progression of heart failure. Interestingly, several studies have found decreased cTnI phosphorylation in late stage human heart failure (Bodor et al. 1997; Messer et al. 2007). Messer et al. (Messer et al. 2007) used a combination of Pro-Q Diamond stain and western blots using cTnI phosphoserine 22/23 antibodies to deduce ~10-fold lower phosphate content at both cTnI PKA and PKC sites with end-stage human heart failure. This raises the intriguing possibility that just a small amount of PKC-mediated cTnI phosphorylation or shifting the ratio of PKA:PKC site phosphorylation is sufficient to yield dominant functional effects especially in the context of declining PKA-mediated cTnI phosphorylation. Clearly, the aforementioned studies also are limited by the fact they capture just a single snapshot in time of the protein profile, while the phosphate state is highly dynamic and affected by a myriad of physiological, pathophysiological, and pharmacological signals. Discernment of the role PKC-mediated cTnI phosphorylation plays in the progression of heart failure will require high resolution proteomic analysis from disease onset through the latter stages of the heart failure syndrome.

In summary, while PKC-mediated cTnI phosphorylation can have a compensatory role to increase contractile efficiency and preserve myocyte biology, its dominant effects over PKA-mediated covalent modulations observed here could have detrimental effects by impairment of cardiac reserve. This could lead to acute mismatches between pump supply and peripheral demands, which may perpetuate physiologic compensatory signals (including G-protein coupled receptor activation) that exacerbate myopathic remodeling and ventricular dysfunction. According to this scenario, PKC-induced phosphorylation of cTnI elicits maladaptive functional consequences that contribute to the etiology of the heart failure syndrome.

References

Aiello EA, Cingolani HE (2001) Angiotensin II stimulates cardiac L-type calcium currents by a calcium and protein kinase C-dependent mechanism. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280:H1528–H1536

Belin RJ, Sumandea MP, Allen EJ, Schoenfelt K, Wang H, Solaro RJ, de Tombe PP (2007) Augmented protein kinase C-alpha-induced myofilament protein phosphorylation contributes to myofilament dysfunction in experimental congestive heart failure. Circ Res 101:195–204

Bilchick KC, Duncan JG, Ravi R, Takimoto E, Champion HC, Gao WD, Stull LB, Kass DA, Murphy AM (2007) Heart failure-associated alterations in troponin I phosphorylation impair ventricular relaxation-afterload and force-frequency responses and systolic function. Am J Physiol 292:H318–H325

Bodor GS, Oakeley AE, Allen PD, Crimmins DL, Ladenson JH, Anderson PA (1997) Troponin I phosphorylation in the normal and failing adult human heart. Circulation 96:1495–1500

Bowling N, Walsh R, Song G, Estridge T, Sandusky G, Fouts R, Mintze K, Pickard T, Roden R, Bristow M, Sabbah H, Mizrahi J, Gromo G, King G, Vlahos C (1999) Increased protein kinase C activity and expression in Ca2+-sensitive isoforms in the failing human heart. Circulation 1999:384–391

Bowman JC, Steinberg SF, Jiang T, Geenen DL, Fishman GI, Buttrick PM (1997) Expression of protein kinase C beta in the heart causes hypertrophy in adult mice and sudden death in neonates. J Clin Investig 100:2189–2195

Braz JC, Gregory K, Pathak A, Zhao W, Sahin B, Klevitsky R, Kimball TF, Lorenz JN, Nairn AC, Liggett SB, Bodi I, Wang S, Schwartz A, Lakatta EG, DePaoli-Roach AA, Robbins J, Hewett TE, Bibb JA, Westfall MV, Kranias EG, Molkentin JD (2004) PKC-alpha regulates cardiac contractility and propensity toward heart failure. Nat Med 10:248–254

Dorn GW, Force T (2005) Protein kinase cascades in the regulation of cardiac hypertrophy. J Clin Investig 115:527–537

Endoh M, Blinks JR (1988) Actions of sympathomimetic amines on the Ca2+ transients and contractions of rabbit myocardium: reciprocal changes in myofibrillar responsiveness to Ca2+ mediated through—and β-adrenoceptors. Circ Res 62:247–265

Fabiato A (1988) Computer programs for calculating total from specified free or free from specified total ionic concentrations in aqueous solutions containing multiple metals and ligands. Methods Enzymol 157:378–417

Goldspink PH, Montgomery DE, Walker LA, Urboniene D, McKinney RD, Geenen DL, Solaro RJ, Buttrick PM (2004) Protein kinase C epsilon overexpression alters myofilament properties and composition during the progression of heart failure. Circ Res 95:424–432

Gray MO, Zhou H-Z, Schafhalter-Zoppoth I, Zhu P, Mochly-Rosen D, Messing RO (2004) Preservation of base-line hemodynamic function and loss of inducible cardioprotection in adult mice lacking protein kinase C-epsilon. J Biol Chem 279:3596–3604

Gu X, Bishop SP (1994) Increased protein kinase C and isozyme redistribution in pressure-overloaded cardiac hypertrophy in the rat. Circ Res 75:1218–1223

Hahn HS, Marreez Y, Odley A, Sterbling A, Yussman MG, Hitty KC, Bodi I, Liggett SB, Schwartz A, Dorn GW (2003) Protein kinase C alpha negatively regulates systolic and diastolic function in pathological hypertrophy. Circ Res 93:1111–1119

Hanft LM, McDonald KS (2009) Sarcomere length dependence of power output is increased after PKA treatment in rat cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol 296:H1524–H1531

Herron TJ, Korte FS, McDonald KS (2001) Power output is increased after phosphorylation of myofibrillar proteins in rat skinned cardiac myocytes. Circ Res 89:1184–1190

Hidalgo C, Hudson B, Bogomolovas J, Zhu Y, Anderson B, Greaser ML, Labeit S, Granzier H (2009) PKC phosphorylation of titin’s PEVK element: a novel and conserved pathway for modulating myocardial stiffness. Circ Res 105:631–638

Huang X, Pi Y, Lokuta AJ, Greaser ML, Walker JW (1997) Arachidonic acid stimulates protein kinase C-epsilon redistribution in heart cells. J Cell Sci 110:1625–1634

Huang L, Wolska BM, Montgomery DE, Burkart EM, Buttrick PM, Solaro RJ (2001) Increased contractility and altered calcium transients of mouse heart myocytes conditionally expressing PKC-beta. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 280:C1114–C1120

Inagaki K, Hahn HS, Dorn GW, Mochly-Rosen D (2003) Additive protection of the ischemic heart ex vivo by combined treatment with delta-protein kinase C inhibitor and epsilon-protein kinase C activator. Circulation 108:869–875

Jideama NM, Noland TA, Raynor RL, Blobe GC, Fabbro D, Kazanietz MG, Blumberg PM, Hannum YA, Kuo JF (1996) Phosphorylation specificities of protein kinase C isozymes for bovine cardiac troponin I and troponin T and sites within these proteins and regulation of myofilament properties. J Biol Chem 271:23277–23283

Kirk JA, MacGowan GA, Evans C, Smith SH, Warren CM, Mamidi R, Chandra M, Stewart AFR, Solaro RJ, Shroff SV (2009) Left ventricular and myocardial function in mice expressing constitutively pseudophosphorylated cardiac troponin I. Circ Res 105:1232–1239

McDonald KS (2000) Ca2+ dependence of loaded shortening in rat skinned cardiac myocytes and skeletal muscle fibers. J Physiol 525:169–181

Messer AE, Jacques AM, Marston SB (2007) Troponin phosphorylation and regulatory function in human heart muscle: dephosphorylation of Ser 23/24 on troponin I could account for the contractile defect in end-stage heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol 42:247–259

Mochly-Rosen D, Wu G, Hahn H, Osinska H, Liron T, Lorenz JN, Yantani A, Robbins J, Dorn GW (2000) Cardiotrophic effects of protein kinase C epsilon: analysis by in vivo modulation of PKC-epsilon translocation. Circ Res 86:1173–1179

Nishizuka Y (1995) Protein kinase C and lipid signaling for sustained cellular responses. FASEB J 9:484–496

Noguchi T, Hunlich M, Camp PC, Begin KJ, El-Zaru M, Patten R, Leavitt BJ, Ittleman FP, Alpert NR, LeWinter MM, VanBuren P (2004) Thin filament-based modulation of contractile performance in human heart failure. Circulation 110:982–987

Noland JR, Kuo TA (1991) Protein kinase C phosphorylation of cardiac troponin I or troponin T inhibits Ca2+-stimulated actomyosin MgATPase activity. J Biol Chem 266:4974–4978

Noland JR, Kuo TA (1993) Protein kinase C phosphorylation of cardiac troponin T decreased Ca2+-dependent actomyosin MgATPase and troponin T binding to tropomyosin F-actin complex. Biochem J 288:2705–2711

Noland JR, Guo X, Raynor RL, Jedeama NM, Avery-Hart-Fullard V, Solaro RJ, Kuo JF (1995) Cardiac troponin I mutants. Phosphorylation by protein kinases C and A and regulation of Ca2+-stimulated MgATPase of reconstituted actomyosin S-1. J Biol Chem 43:25445–25454

Pi Y, Walker JW (2000) Diacylglycerol and fatty acids synergistically increase cardiomyocyte contraction via activation. Am J Physiol 279:H26–H34

Pi Y, Zhang D, Kemnitz KR, Wang H, Walker JW (2003) Protein kinase C and A sites on troponin I regulate myofilament calcium sensitivity and ATPase activity in the mouse myocardium. J Physiol 552:845–857

Puceat M, Clement O, Lechene P, Pelosin JM, Ventura-Clapier R, Vassort G (1990) Neurohormonal control of calcium sensitivity of myofilaments in rat single heart cells. Circ Res 67:517–524

Qui Y, Ping P, Tang XL, Manchikalapudi S, Rizvi A, Zhang J, Takano H, Wu WJ, Teschner S, Bolli R (1998) Direct evidence that protein kinase C plays an essential role in the development of late preconditioning against myocardial stunning in conscious rabbits and that epsilon is the isoform involved. J Clin Investig 101:2182–2198

Sakthivel S, Finley NL, Rosevear PR, Lorenz JN, Gulick J, Kim S, VanBuren P, Martin LA, Robbins J (2005) In vivo an in vitro analysis of cardiac troponin I phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 280:703–714

Scruggs SB, Hinken AC, Thawornkaiwong A, Robbins J, Walker LA, de Tombe PP, Geenen DL, Buttrick PM, Solaro RJ (2009) Ablation of ventricular myosin regulatory light chain phosphorylation in mice causes cardiac dysfunction in situ and affects neighboring myofilament protein phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 284:5097–5106

Strasser RH, Briem SK, Vahl CF, Lange R, Hagl S, Kubler W (1996) Selective expression of cardiac protein kinase C-isoforms in chronic heart failure. Circulation 94(suppl I):I–551

Sumandea MP, Pyle WG, Kobayashi T, deTombe PP, Solaro RJ (2003) Identification of a functionally critical PKC phosphorylation residue of cardiac troponin T. J Biol Chem 278:35135–35144

Takeishi T, Ping P, Bolli R, Kirkpatrick DL, Hoit BD, Walsh RA (2000) Transgenic overexpression of constitutively active protein kinase C epsilon causes concentric cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res 86:1218–1223

Terzic A, Puceat M, Clement O, Scamps F, Vassort G (1992) Alpha-1 adrenergic effects on intracellular pH and calcium and on myofilaments in single rat cardiac cells. J Physiol 447:275–292

Van der Velden J, Narolska NA, Lamberts RR, Boontje NM, Borbely A, Zaremba R, Bronzwaer JG, Papp Z, Jaquet K, Paulus WJ, Stienen GJ (2006) Functional effects of protein kinase C-mediated myofilament phosphorylation in human myocardium. Cardiovasc Res 69:876–887

Venema R, Kuo JF (1993) Protein kinase C-mediated phosphorylation of troponin I and C-protein in isolated myocardial cells is associated with inhibition of myofibrillar actomyosin MgATPase. J Biol Chem 268:2705–2711

Vlahos CJ, McDowell SA, Clerk A (2003) Kinases as therapeutic targets for heart failure. Nat Rev 2:99–113

Wakasaki H, Koya D, Schoen FJ, Jirousek MR, Ways DK, Hoit BD, Walsh RA, King GL (1997) Targeted overexpression of protein kinase C beta2 isoform in myocardium causes cardiomyopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:2189–2195

Zhang ZH, Johnson JA, Chen L, El-Sherif N, Mochly-Rosen D, Boutjdir M (1997) C2 region-derived peptides of beta-protein kinase regulate cardiac calcium channels. Circ Res 80:720–729

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the late Dr. Jeffrey W. Walker for insightful and poignant discussion related to the PKC effects on cardiac myocyte biology. This work was supported by an American Heart Association (Heartland Affiliate) Postdoctoral Fellowship (0825725G) to L.M.H. a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant (R01-HL-57852) to K.S.M., (P01 HL 062426) to R.J.S., and (T32 HL 07692) to A.C.H. and S.B.S.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hinken, A.C., Hanft, L.M., Scruggs, S.B. et al. Protein kinase C depresses cardiac myocyte power output and attenuates myofilament responses induced by protein kinase A. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 33, 439–448 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10974-012-9294-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10974-012-9294-9