Abstract

Primary/elementary teachers are uniquely positioned in terms of their need for ongoing, science-focused professional development. They are usually generalists, having limited preparation for teaching science, and often do not feel prepared or comfortable in teaching science. In this case study, CHAT or cultural–historical activity theory is used as a lens to examine primary/elementary teachers’ activity system as they engaged in a teacher-driven professional development initiative. Teachers engaged in collaborative action research to change their practice, with the objective of making their science teaching more engaging and hands-on for students. A range of qualitative methods and sources such as teacher interviews and reflections, teacher-created artifacts, and researcher observational notes were adopted to gain insight into teacher learning. Outcomes report on how the teachers’ activity system changed as they participated in two cycles of collaborative action research and how the contradictions that arose in their activity system became sources of professional growth. Furthermore, this research shows how the framework of activity theory may be used to garner insight into the activity and learning of teachers as both their professional activities and the context change over time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

While conceptions of what constitutes effective professional development (PD) for teachers are well established in the research literature, challenges remain prevalent in teachers’ access to PD. Furthermore, even if PD is available, it may not be responsive to teachers’ needs (Goodnough, Pelech, & Stordy, 2014; Day & Sachs, 2004; Murray, 2014). The most common teacher-focused forms of PD recognize that professional learning encompasses more than developing technical knowledge or learning new skills. Rather, effective professional development occurs when it allows teachers to explore the “social relations and the overlapping knowledge, theories and beliefs that direct professional action” (Fairbanks et al., 2010, p. 166). Common characteristics of effective professional development focus on developing teacher content knowledge and understanding of how students learn the content (Meiers, Ingvarson, & Beavis, 2005); engaging teachers in active learning that is sustainable; offering ongoing teacher support that is relevant and based on teacher needs: and fostering collective participation (Garet, Porter, Desimone, Birman, & Yoon, 2001; Steiner, 2004; Supovitz, Mayer, & Kahle, 2000; Timperley, 2008; Wilson & Berne, 1999).

Primary/elementary teachers are uniquely positioned in terms of their need for ongoing, science-focused PD. They are usually generalists, having limited preparation for teaching science, and often do not feel prepared or comfortable in teaching science. This is well documented in the research literature (e.g., Smith & Anderson, 1999; Tilgner, 1990). These teachers may address the challenge of teaching science by relying too heavily on textbooks, overusing outside experts, adopting traditional approaches to teaching science and ignoring science entirely; so, it becomes a marginalized subject in the school curriculum (Davis, Petish, & Smithey, 2006; Holroyd & Harlen, 1996; Murphy, 2012; Murphy, Neil, & Beggs, 2007; Trumper, 2006; Zembal-Saul, Blumenfeld, & Krajcik, 2000).

In this study, CHAT or cultural–historical activity theory (Engeström, 1987, 2001) is used as a lens to examine primary/elementary teachers’ activity system as they engaged in a professional development initiative. Collaborative action research (AR) (Greenwood & Levin, 2006; McNiff, 2013) was used as a strategy to engage teachers in targeting their objective. Many studies have reported on the positive impact of AR on teacher professional learning (e.g., teacher identity, pedagogical content knowledge) and educational change (Eilks & Markic, 2011; Johannessen, 2015; Mak & Pun, 2015; McIntyre, 2005). A modest body of research is emerging that examines teacher learning through the lens of CHAT (Hume, 2012; Sezen-Barrie, Tran, McDonald, & Kelly, 2014; Zimmerman, Morgan, & Kidder-Brown, 2014).

In terms of practicing teachers, a handful of studies have focused on science education and teacher learning using CHAT. For example, Dubois and Luft (2014) examined the affordances and constraints that beginning secondary science teachers experience as they float from class to class (not having their own classroom) and the impact on their development and instruction. Thomas and McRobbie (2013), in the context of two groups of chemistry students, showed how changes in the teachers’ pedagogy impacted student metacognitive processes and reflection as it related to learning chemistry. Clark and Groves (2012) studied primary teachers’ identity development (emotions, beliefs, and backgrounds) as they adopted practical activities in teaching science. In another study of primary teachers’ learning in science, Fraser (2010) explored the teachers’ subject and pedagogical content knowledge through continuing professional development and the constraint and barriers that impacted their teaching of science. These studies used CHAT as an analytical framework to better understand the complexities of learning, taking into consideration the social, cultural, and historical dimensions of practice (Loxley, Johnston, Murchan, Fitzgerald, & Quinn, 2007; Newmann, King, & Youngs, 2000; Opfer & Pedder, 2011).

In this study, the author used activity system analysis to describe teachers’ experiences, to document their changing objective as they engaged in collaborative AR, and to examine how contradictions or tensions became sources of change for the teachers. The following research questions guided the study: (a) How will teachers’ activity system change as they participate in professional learning through AR? (b) What contradictions will arise in their activity system? (c) How will the contradictions that arise in their activity system become sources of learning?

Cultural–Historical Activity Theory

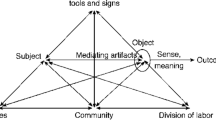

In the last two decades, CHAT has emerged as a theoretical framework to capture the complex nature of human learning in many disciplines and contexts. For example, Jonassen and Rohrer-Murphy (1999) argued that CHAT provides a better framework than traditional methods for analyzing needs, tasks, and outcomes for designing constructivist learning environments. Roth and Lee (2007) examined the growth of CHAT in research and viewed it as a theory for praxis, providing a fruitful way to “overcome some of the most profound problems that have plagued both educational theorizing and practice” (p. 186). CHAT has been applied to workplace learning (Engeström, 2000), as well as to the design and adoption of technology (Kaptelinin & Nardi, 2006; Uden, 2006). The appeal of the framework is that it provides a means to understand human interactions in natural settings. Nardi (1996) states, “the object of activity theory is to understand the unity of consciousness and activity … consciousness is not a set of disembodied acts” (p. 7). Rather, consciousness is part of everyday actions and activity, embedded in social contexts. Vygotsky (1978, 1986), one of the initial contributors to CHAT, developed the notion of mediation. He hypothesized that artifacts (e.g., physical and language tools) mediate all human action. In moving beyond the focus on the individual, Leontiev (1981) conceptualized human activity as individuals taking action as part of collective social activity incorporating other elements such as community, division of labor, and rules. Engeström (1987) further developed CHAT, resulting in the model that has become the basic unit of analysis for the theory. Engeström (1987) presented the elements and their interconnections visually in the now well-known “triangle” (refer to Fig. 1). The socially mediated elements include subject, object, tools, community, norms, and division of labor.

When analyzing activity systems, the subjects are the individuals from whom the viewpoint is adopted; the subjects are the eye or at the center of the activity system (Engeström & Miettinen, 1999). The subjects work toward an object, which can be a goal, motive, or products that result from engaging in the activity. The subject and object are mediated by tools, which may be material or psychological, such as computers, language, teaching strategies, for example. In other words, subjects use tools to reach their object. The community is the social group to which the subjects belong, while norms may be customs, guidelines, standards, or established practices that enhance or hinder community activity and functioning. In order for subjects to achieve their object or goals, there needs to be a division of labor within the community. Bellamy (1996) refers to the division of labor as “… the role each individual in the community plays in the activity, the power each wields, and the tasks each is held responsible for” (p. 125). The activity system results in outcomes that may lead to innovation, change, or expansive learning (Anthony, Hunter, & Thompson, 2014; Engeström, 2001).

In this study, changes in the activity system of a group of primary/elementary teachers are described. As well, contradictions are identified and examined to determine how they enabled the teachers to change their object or motive, and hence the outcome of their work.

Within an activity system, contradictions or disconnects may occur within or between activity systems (Center for Activity Theory and Developmental Work Research, 2003–2004; Engeström, 1987). They accumulate over time and can only be understood in terms of the historical and sociocultural context of practice in which they are embedded.

Methodology/Methods

The Context of the Study

AR, adopted in this study as a professional development strategy, has been used in teacher education as a means for practitioners to systemically examine their classroom practice (Mills, 2010; Stringer, 2013). It is “… simply a form of self-reflective enquiry undertaken by participants in social situations in order to improve the rationality and justice of their own practices, their understanding of these practices, and the situations in which the practices are carried out” (Carr & Kemmis, 1986, p. 162). It has been adopted for a variety of purposes such as changing teachers’ pedagogic practice and thinking, examining classroom assessment, and cultivating communities of practice (Hanafin, 2014; Mak & Pun, 2015; Yin & Buck, 2015). Because action research is collaborative, systematic, data-driven, and focused on teacher and student learning, it is an effective means to engage practitioners in professional development (McNiff & Whitehead, 2011; Mills, 2010).

During their AR project, the teachers worked with a student population that was ethnically and linguistically diverse, having three or four students in each class who were English as a second language (ESL) learners. Two grade one classes and two grade four classes participated in the project in each year. Class sizes ranged from 15 to 25 in each year of the project. The teachers worked in a small, urban K-6 school in Newfoundland with 230 students and a total of 23 teachers.

The Participants

In this study, the teachers completed two cycles of AR. In year one (2013–2014), five teachers participated (Anne, Ingrid, Alice, Harriet, and Astrid; these names are pseudonyms). In year two, three of the teachers continued to be part of the team (Anne, Ingrid, and Alice), and two new teachers, Laura and Lisa (pseudonyms), joined the team. Harriet took a maternity leave so did not continue in the second year, and Astrid was transferred to a new school. Two of the teachers had <4 years of teaching experience, while the others had been teaching for 12–20 years.

The Teachers in Action Program

The Teachers in Action (TIA) program, a 5-year program focused on K-6 teachers’ professional learning in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM), was in its second year when this study occurred. The funding for the program was a contribution from a local oil consortium in Newfoundland and Labrador. The main goals of this program are to support K-6 teachers in becoming more confident in teaching in STEM subjects and to assist them in adopting inquiry-based approaches to teaching and learning in STEM. While teaching and learning through inquiry varies in meaning and takes various pedagogic forms (Anderson, 2002; Chin, 2007; Minner, Levy, & Century, 2010), in the context of this program, scientific inquiry is guided by a conception found in the curriculum framework documents of the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. Scientific inquiry involves engaging students in “posing questions and developing explanations for phenomena … [through] questioning, observing, inferring, predicting, measuring, hypothesizing, classifying, designing experiments, collecting data, analysing data, and interpreting data …”(Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, 2004, p. 4).

Teachers were recruited through an application process, which is supported by the local school district. The school-based team in this study was part of the larger program which supports school-based teacher groups ranging in size from 2 to 8. They were chosen as a focus for this paper, as the team was representative of the changes, complexities, and contradictions that were experienced by many of the other teams in TIA. In each year of the program, 70–80 teachers engage in inquiry through collaborative AR. They are supported with classroom-based resources, release time to work on their inquiry projects (7 days per teacher), and a TIA leadership team consisting of the author (project lead), a full-time professional development facilitator, a part-time coordinator, and graduate students. Through ongoing face-to-face meetings (35–40 h of time), online meetings that occurred throughout the process, and communication by e-mail, the leadership team provides ongoing support, guidance, and facilitation as the teachers plan and implement their projects. A member of the leadership team works with each teacher group during all stages of the AR cycle. For example, leadership team members are part of most planning and debriefing meetings, help with securing resources, offer advice on pedagogical issues, assist teachers with understanding scientific and mathematical content and principles, and act as sounding boards as the project unfolds. Topics are chosen based on the interests and needs of the participating teachers.

The Action Research (AR) Cycles

Teachers were introduced to teacher inquiry and AR during a 2-day institute that was held in August of year one. The AR cycles involved teachers in planning a change, implementing the change, observing the outcomes of the change, and reflecting on the outcomes of the change (Kemmis & McTaggart, 2005). During the institute, the topics included the nature of AR, what it is, and how it is conceptualized; how to identify an area of focus; how to plan a study and formulate research questions; and how to collect and analyze data in relation to those questions. The institute also introduced teachers to various approaches to teaching and learning STEM through inquiry, such as understanding the nature of science, how to design assessment and pedagogical inquiry-based activities, and how to make learning more student-centered.

Planning in each year occurred from September to December; implementation occurred from January to June and continued into the summer as part of the teachers’ project required attending to and maintaining a school-based garden. The teachers used 3 days in the fall to prepare a plan of action to guide their work. The author attended these days and provided guidance and support as the teachers generated a plan of action. This plan included a timeline, research questions, relevant literature, activities related to school- and classroom-based implementation, data collection and analysis, ethics, and sharing and dissemination. One member of the TIA leadership team was present at all planning sessions. Debriefing sessions (4 days) with the group during and after implementation occurred as well. A member of the leadership team helped the teachers during these meetings to analyze and interpret their data. The broad focus of the project was to help students develop positive attitudes about healthy eating. More specifically, the teachers posed this research question: How will the garden-based food project affect students’ understandings and attitudes about healthy eating? The project connected to both science and health curriculum outcomes in grades one and four in the Newfoundland and Labrador science curriculum (see http://www.ed.gov.nl.ca/edu/k12/curriculum/guides/science/). Examples of knowledge and skills targeted include identifying local habitats and their associated plant and animal populations, comparing the structural feature of plants, predicting how the removal of a plant or animal population affects the community, stating hypotheses and predictions based on observed patterns, communicating procedures and results, and describing how personal actions impact living things and their environments.

Because the teachers needed to strengthen their content knowledge as it relates to plant growth in Newfoundland (e.g., life cycles, growing requirements, nurturing a garden) and their pedagogical content knowledge for teaching through inquiry, the team engaged in reading literature and working with a horticulturalist. Next, letters were sent home to parents, seeking permission for students to be involved in the project. A variety of classroom-based learning activities was implemented focused on examining food sources: planning and preparing balanced meals; determining the role of nutrients in the diet; describing the relationship among diet, well-being, and physical activity; developing inquiry skills of observing, classifying, and communicating ideas; and describing the life cycles of plants. Other learning experiences included visiting a supermarket, facilitated by a nutritionist; planning and preparing a meal with the support of local chefs; and planting and maintaining a vegetable garden and then harvesting the vegetables.

To answer their research questions, the teachers used a pre- and post-questionnaire to examine student attitudes about nutrition and healthy eating, student-generated work samples, notes from their collaborative planning/debriefing meetings, student classroom observational notes and pictures, and their own individual journal reflections. The teachers collected and analyzed data as implementation was occurring, reflecting individually and collaboratively on what students were experiencing and understanding. Collaborative reflection occurred during planning and debriefing meetings (7 days in each year), and individual reflections were created by the teachers as they made sense of their classroom observations and interpretations. These individual electronic entries ranged in frequency from 5 to 10 by each teacher. Both types of reflections focused on their own professional thoughts and actions as well as how their action were impacting student learning.

At the end of implementation in each year, the teachers reviewed their data more intensively and created a multimedia presentation which was shared will all teachers in TIA at a final conference. They also participated in post-project interviews with a member of the leadership team. Teachers, parents, and students cared for the school-based garden over the summer months when school was closed.

In year two, the teacher team completed another cycle of AR as described above. They engaged their students in many of the same learning activities (e.g., planting and maintaining a school garden and examining food sources), but the object or goal of their project shifted. Their new research question became, “How can a school-home partnership foster students’ healthy well-being using a school garden food project?”

They extended their data collection to not only include students, but also include parents. They invited parents to participate in events related to the project, such as a field trip to a local supermarket, planting the garden, and attending classroom sessions by health experts. Informal conversations with parents became sources of data. Another communication and data collection source involved implementing student–parent–teacher communication notebooks. These were sent home regularly and reviewed students’ classroom learning and activities related to the project and asked parents to respond to a few questions.

Data Methods and Sources

The author adopted a constructivist paradigm in this study, thus allowing insights into the “participants’ views of the situation being studied” (Creswell, 2003, p. 8). Qualitative research methods and sources allowed for dialog and interaction between the teachers and researchers as they collaboratively constructed an understanding of how their activity system was changing.

Data collection and analysis were ongoing over the 2-year period, using five sources, including a pre-implementation inquiry brief; teacher reflections; post-implementation semi-structured interviews; a teacher-created multimedia presentation; and researcher notes. The data collected by the teachers were not used as part of this analysis in creating a portrait of the teachers’ changing activity system.

Inquiry Brief

The inquiry brief was provided to the teachers to assist them with planning their AR projects and was later used to guide the implementation of their project. Components of the brief included a research focus, teacher research question, literature that informed the project, data collection methods and sources, ethical considerations, curriculum goals and outcomes to be targeted, assessment and learning activities, and data collection methods and sources. It was also a tool to help teachers reflect on their project as it unfolded and a source of data for the researcher to corroborate observations during school-based visits.

Teacher Reflections

The teacher reflections were used to encourage the teachers to consider their decisions and actions as they engaged in AR. Teachers completed reflections during the implementation stage of the project using a tool called Evernote (2015), a cross-platform (iPad and web-based) tool designed for notetaking, organizing, and archiving. These reflections were shared with the researcher and professional development facilitator. The following are examples of questions that were used by the teachers to guide their reflections: (a) Describe, briefly, what was implemented or done during the week. (b) How did students respond to the implementation? Did implementation go as expected? Why or why not?

Interviews

Each teacher was interviewed for 60 min at the end of the AR cycle in years one and two, and the interviews were later transcribed. Questions were based on four broad themes: (a) teachers’ changing knowledge and classroom practice (e.g., how have your beliefs about teaching and learning in STEM changed during the project?), (b) student learning (e.g., what was the role of your students in your classroom during the project?), (c) the AR process (e.g., what challenges and/or tensions did you experience during the AR process?), and (d) future directions (e.g., will you continue to use the concepts and tools adopted in the project?). The interview protocol was validated by asking three experienced teacher researchers to review the questions for clarity. The questions aligned with the broad goals of the TIA program.

Multimedia Artifact

The artifact was a 10-min video that incorporated music, text, and graphics. It provided an overview of their project, the activities they engaged in during the AR cycle, and the outcomes of the project for themselves and their students. This artifact was constructed collaboratively by the group and helped them consolidate their learning. The text of the video was transcribed and used as a data source and later shared at a conference with other teachers. One video was completed at the end of each year.

Researcher Notes

The author or a member of the research team recorded notes during 14 group planning/debriefing sessions (5–6 h per day) over a 2-year period. These notes focused on what the teachers did pre- and post-implementation, their emerging insights about changes in their practice and student learning, and the systemic tensions they had and were experiencing in their work. Ten classroom-based visits occurred per year. During classroom-based visits (at least two visits to each teacher’s class), notes were recorded based on informal conversations with the teachers before and after the implementation of lessons, as well as during classroom teaching. The latter observations reflected what the teachers said and did. This allowed the researcher to determine the fidelity between the teachers’ reports of their thinking and actions and their actual classroom practice.

Data Analysis and Reporting

All data collected over two cycles of AR were aggregated into one file, with all text being read and re-read by two researchers. Next, through a process of deductive analysis, units of text were coded according to the key elements of the CHAT activity system (subject, object, tools, community, division of labor, norms or rules, and outcomes). Coding into each category was guided by questions derived from Engeström (1987, 2001), as follows: (a) Subject: Who is the focus of the activity system? What are their characteristics? (b) Object: What do these individuals want to learn? Why do they engage in the activity? (c) Tools: What conceptual or physical tools are being used by individuals to achieve their object? (d) Division of Labor: How is power and control distributed within the activity system? (e) Norms: What practices or conventions constrain or hinder the activities of the individuals? (f) Community: Who is working with and supporting individuals as they engage in the activity? (g) Outcomes: What are the key results of engaging in the activity? These categories were applied to the overall data.

Within each category, further sub-codes were identified. For example, in the “subject” category, sub-categories included feelings about teaching science (e.g., lacking confidence), beliefs about science teaching and learning (e.g., science should be inquiry-based), and demographic information (e.g., years of teaching). In addition, coding involved identifying contradictions in the teachers’ activity system.

Once the portraits of teachers were developed at the end of each cycle of AR, the portraits were sent to the teachers for member checking and feedback (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). This contributed to increasing the credibility of the research findings. To further ensure the trustworthiness of the study, the author used triangulation, gathering data from various sources to corroborate findings. Data collection and analysis were ongoing, while more intensive data analysis was conducted by the author at the end of each AR cycle. This allowed for congruence to be established between the objectives of the research and implementation. In addition, the author generated reflective notes throughout the design and implementation process, thus allowing her to monitor her own developing understanding of emerging themes and patterns in the data (Shenton, 2004).

Outcomes

In the analysis below, the teachers’ changing activity system is described (subjects, object, tools, norms, community, and division of labor), thus addressing the first research question: How will the teachers’ activity system change as they participate in professional learning through AR? Next, contradictions in the teachers’ activity systems (nature of professional learning, classroom practice, and parental involvement) are identified and how they became sources of learning is also described. This addresses the second and third research questions.

The Teachers’ Activity System

Subjects

Except for one teacher in the project, all reported that they did not feel comfortable teaching science. They felt their teaching of science was “dry” and they “spent too much time relying on the textbook” (Reflections, Alice, Anne, Ingrid). Alice not only felt uncomfortable teaching science, she also “avoided science” and was “afraid to take on something new” (Final interview). Four of the mid-career teachers said that “most of the time is spent on mathematics and language” (Planning meeting). Lisa, while a seasoned teacher, had spent the last 10 years in special education, providing support to regular classroom teachers and students. This was her first year having responsibility for a regular classroom; thus, she “felt like a first year teacher all over again” (Planning group meeting). Ingrid was the only teacher, at the beginning of the project, who described herself as “teaching through a hands-on approach” (Planning group meeting). Having completed a science degree, she felt comfortable teaching science and often integrated art and science outcomes, as art was also a formal area of study for her. Interestingly, the two early career teachers, Astrid and Lori, had been exposed to inquiry-based teaching and learning during teacher preparation, but really had limited experience in how to structure and implement inquiry-based learning environments. As a recent graduate, Astrid stated that her professors “preached hands-on learning, hands-on learning.” She understood the nature of inquiry-based learning, but with limited experience, she did not feel “safe or secure” in creating activities that placed students at the center of learning in science. These comments were shared in a reflection.

Object

The idea for this project started with Anne; it had been something she “wanted to do for a long time” (Interview). Anne was the school assistant principal and taught grade four science in one of the classrooms, but also had responsibilities as a learning resource teacher for the staff. In addition to creating a school garden, she wanted to make inquiry learning a focus of the project. Prior to starting the project, the author was invited to the school by the principal to give a presentation about the TIA program. After the meeting, Anne discussed her idea with the principal and the author to determine its feasibility. Subsequently, she talked to other staff to see who would be interested in the project, and in the first year formed a team of five teachers. At an early group planning meeting, the teachers shared their reasons for joining the project. Ingrid, became part of the project, as it provided “funding, resources, and time” to engage in self-directed professional development. The nature of the project allowed her to engage students in more guided inquiry in science, aligning with her belief that “children learn from doing, seeing, and mucking into things.” Alice joined the project, although she was “skeptical about how it would all work.” She wanted to make learning in science more student-centered, but the project seemed to be “a big undertaking.” Harriet and Astrid wanted to become more “comfortable with the science outcomes,” as well as to “try something new, exciting, and different.” In the second year of the project, Astrid and Harriet were no longer part of the project. Laura and Lisa became part of the team. Laura viewed the project as an opportunity to gain more insight into how to “support inquiry” and to help her students “take more responsibility for learning.” Likewise, Lisa wanted to move away from teaching science as “a textbook deal.”

In year one of the project, the teachers completed one cycle of AR. In addition to the above goals for enhancing their own personal, professional practice, their shared goal for the project was to help their students develop a deeper understanding of and positive attitudes toward healthy eating. As a result of what was learned in the first year of the project, the teachers expanded their object in year two, the second AR cycle, to try to “connect healthy living with the home, and basically get parents at home more involved” (Anne, Interview). They “hoped that … [they] … would get parents more involved” in helping their children adopt healthier lifestyles (Ingrid, Interview).

Tools

In activity theory, tools may serve several purposes in learning, such as to meet goals and purposes, to find solutions to problems, to mediate thoughts and actions, and to represent cultural and knowledge development (Kuutti, 1996; Murphy & Rodrigues-Manzananares, 2014). The teachers used a variety of tools to help them achieve their object of improving their own teaching in science through inquiry, as well as helping their students become aware of and enact healthy lifestyles. The overall professional development strategy was collaborative AR. Engaging in cycles of action was a tool that allowed them to conceptualize and implement a classroom-/school-based research project. During the process, an inquiry brief guided their planning and implementation. Posing research questions, reviewing and interpreting literature related to their research topic, planning classroom interventions to address their research questions, and collecting and analyzing data were essential tools as they completed two cycles of AR. For example, the teachers administered a pre- and post-assessment survey “using a ShowMe app. [Students] drew pictures of and talked about what healthy, well-balanced meals would look like… using data collection tools was part of … [their] … inquiry process” (Reflection, Laura).

In addition to the AR tools, the teachers used several technological tools to support the planning and implementation of their project. Google docs was a new tool for all of the teachers, except Laura, and was used to complete their student surveys. It also served as a way for the teachers to share and store files related to project work. Evernote was recommended to the teachers by the TIA facilitators to record their ongoing insights as the project unfolded. The tool was used to varying degrees by the teachers. The photograph and video aspects of the iPads were also used by the teachers as “digital proof of students’ work” and they “started to record the students doing science, visually with pictures and videos” (Anne, Reflection). Other classroom pedagogical tools used by the teachers to target their outcomes were curriculum documents, outside speakers and partners (e.g., farmer, chef), garden materials, field trips to a local supermarket, student–parent–teacher communication notebooks, varied inquiry-based approaches and strategies, and consumable materials.

Norms

Norms are explicit and implicit guidelines or standards and practices that govern or regulate an activity system. As prescribed by the provincial Department of Education, the science curriculum outcomes were used by the teachers to guide the content, skills, and attitudes that would be emphasized in the curriculum. While the teachers traditionally were very good at integrating curriculum outcomes from other subject areas, integrating science with other subject areas was new. Now they were “looking at things more as a whole” and being selective about which outcomes to target (Lisa, Interview). With the exception of one teacher, they described their pre-project teaching as being “traditional in science” and relying “too heavily on the text” (Group planning meeting). This changed during the project, as the teachers created a “more student-based, more hands-on, more inquiry-based curriculum” (Interview, Alice). As Harriet shared during a planning meeting, “we had the opportunity to work with the chefs, to go on a fieldtrip to the grocery store, and then afterward have the little session with the dietician and the scavenger hunt. So the opportunity for them to learn in a different way was good!”

Having sufficient time to engage in teacher-centered professional development was not the norm for these teachers. In fact, when asked whether they had participated in any science professional development over the last 3–5 years, the teachers said that there were no opportunities available to them in science. So, having time to engage in collaborative inquiry was new. “Typically [teachers] get pushed into a room and everybody’s there, whether it’s something you’re interested in or not” (Anne, Group debriefing meeting).

Community

By joining the TIA program, the teachers had an opportunity to extend the community that supported their work, helping them to focus on their object of adopting inquiry-based learning in science and improving students’ understanding of and attitudes toward healthy eating. While the teachers felt they worked in a very supportive school community, this project gave them the opportunity to get to know their other team members better. Ingrid noted in a planning meeting, for example, that she “now felt very close to some of the primary teachers that … [she] … probably wouldn’t have known very well” prior to the project. The teachers’ community also included a “number of experts from outside the school such as a nutritionist, a farmer, and local restaurant chefs” (Lisa, Interview). The principal also attended some of the planning meetings and played a key role in supporting the teachers, but was not involved in teaching. In this type of time-intensive teacher inquiry, “a lot of support is needed. [The teachers] received a lot of support from the TIA team” (Harriet, Researcher notes). The TIA team (the author, a professional development facilitator, graduate students, and a coordinator) was part of the teachers’ new community. “In the second cycle of the project, the community expanded again to include parents. The teachers “got the parents involved; the connection between home and school was really important to … improve the home–school connection” (Laura, Debriefing meeting).

Division of Labor

Within the teacher inquiry group, in both years, Anne assumed the strongest leadership role. While tasks were shared, a lot of the coordination became Anne’s responsibility. While all teachers participated fully in the planning/debriefing days and all engaged in finding resources, planning activities, and implementing their projects, some role differentiation did occur. For example, Laura, who was part of the team in year two, was comfortable with technology, so “took on the role of the iMovie this year … [the group] trusted [her] abilities in the tech aspect, to be able to put it together and do a good job on it” (Reflection).

In addition to a division of labor among the teacher inquiry team, a shift in the division of labor occurred in the teachers’ classrooms. They moved from teacher-directed teaching in science, where the power in the classroom resided primarily with the teacher, to “giving [students] more time to answer their questions, stepping back and allowing them to figure it out and come to their own conclusions” (Anne, Debriefing meeting). The teachers agreed that they never wanted to go back to a reliance on the textbook and wanted to continue to create learning environments where students could “be autonomous,” “explore and discover,” “collaborate in groups,” and “be engaged in their learning” (Anne, Ingrid, Lisa, Debriefing meeting).

Contradictions as a Source of Learning

Addressing the contradictions in their activity system engaged the teachers in doing things in new ways, which resulted in changes in their thinking and practice. “Contradictions can drive transformations in future activities and portray how human activities are tied to several complex phenomena” (Yamagata-Lynch, 2010, p. 8).

The Nature of Professional Development

Traditionally, teacher professional development in science in Newfoundland and Labrador (and in many other jurisdictions) has been limited to in-servicing where new curricula are introduced or one-shot workshops are offered. Furthermore, the teachers in this study talked about their experiences with PD in science; “this is the only PD that [we] have had recently where [we] get the time to actually collaborate and work things through as a team. …” (Astrid, Planning meeting). By participating in the TIA project, new tools and an extended community allowed the teachers to modify their approaches to how to teach science. While they had a desire to do this in the past, without the tools and supports to do so, they were not positioned or comfortable in making changes to their classroom practice.

Becoming a researcher in their own classrooms was a new role for the teachers as well. This was not part of their typical approach to personal, professional development. By adopting the tools of AR (the AR inquiry cycle, reviewing the literature, data collection methods), the teachers were able to scrutinize their actions and the outcomes of those actions in a systematic way. In the past, the teachers did not have this opportunity to “question the best way to teach … [or to] question their own practices” (Anne, Reflection). The teachers found answers to their research questions, creating changes in the object of their activity system and the learning environments in their classrooms. Although there were challenges during the AR process, such as organizing and analyzing data and becoming comfortable with “letting go of the classroom control” (Astrid, Interview), this tangible change became the impetus and motivation for them to continue with a second cycle of AR.

The teachers had opportunities in the project to work with teachers and other educators outside the school. For example, they utilized the expertise of a horticulturalist and a local farmer to assist them with setting up and maintaining their garden. Communication and collaboration were enhanced, thus allowing for change to occur in their activity system. For the teachers, it “made [them] reflect, engaging [them] in asking more questions” (Harriet, Reflection). At times, they felt it was “overwhelming,” but the AR process “gave [them] a way to be motivated and take control of [their] learning” (Alice, Interview).

Classroom Practice

By changing their role as teachers of science, the teachers were able to address a long-standing contradiction of primary–elementary teachers: not being comfortable or confident in teaching science as a result of not having strong science content knowledge or an understanding of how to structure science teaching and learning through inquiry. The teachers reported that they enhanced their content knowledge as it relates to nutrition and plant growth and life cycles as evidenced in a debriefing meeting: “We have definitely become more knowledgeable about this content and more confident” (Anne). Furthermore, they held beliefs that valued inquiry. The project “helped [them] become more familiar with curriculum outcomes” and “to become more comfortable” in teaching science (Ingrid, Interview). They reported that they “were now facilitators of learning,” “allowed students to pose their own questions,” “used I-wonder questions,” and “allowed [students] more time to figure things out” (Anne, Alice, Laura, Reflections). During the project, “children’s attitudes about healthy eating changed pretty significantly. They are now talking about and assessing what is and is not healthy” (Laura, Interview). Laura further noted, “At the beginning, many of the younger children did not really “understand that food comes from animals and plants.” In addition, the division of labor in the learning environment shifted to where power was shared more equitably between the teachers and their students. Students had more autonomy, “having more time to answer their own questions … and to come to their own conclusions” (Alice, Debriefing meeting). The teachers acknowledged that this shift from teacher-centered teaching to creating a student-centered learning environment “was not easy at first. It required a shift in [their] thinking about the role of the teacher” (Anne, Reflection).

Parental Involvement

The school had a supportive parental community. There was a high level of parental involvement in all school activities ranging from fund raising to supporting teachers during informal school outings. However, the teachers in the project rarely asked parents to be directly involved with their children’s classroom learning in an ongoing manner. At the end of year one of the project, it became apparent to the teachers that they needed to encourage “parents to be more connected to the project” so “parents and teachers could be on the same page” (Anne, Interview). They were able to garner more parental involvement in their project, but not to the extent they wished. As Lisa shared in a debriefing meeting, “Parents get a lot of feedback—just report cards or agendas. They get to know what’s going on, but they don’t really know what’s happening in the classroom.” After the first year, the children knew what healthy eating was and what healthy food was, but because of their home environment, they “had little control over what’s actually given to them” (Lisa, Reflection). While the teachers had some success with parents, the level of involvement “was not as high as they had hoped. It is not something (parent involvement and family healthy eating) [they] were going to change overnight” (Ingrid, Debriefing meeting). The teachers felt that this contradiction was still unresolved at the end of the project.

Conclusions

This study described the changing activity system of a school-based group of action researchers as they engaged in a new form of professional development (new to them) and adopted student-centered inquiry pedagogy. It also identified the contradictions that existed in their activity system and how they were addressed.

As a result of participating in a teacher-centered form of professional development focused on the teachers’ needs and the needs of their students, the teachers became more confident teachers of science, enhanced their pedagogy, and were able to successfully address some of the contradictions in their activity system. The goal of having parents more fully involved in helping their children embrace active living and healthy eating was not fully realized. Based on the teachers’ review of the literature and the potential for parents to be strong socializing agents for their children (see, Jeynes, 2005, 2007; Savage, Fisher, & Birch, 2007), the teachers had determined it would be feasible to introduce strategies to engage parents in their children’s learning (e.g., student–parent–teacher communication notebooks, parents participating in field trips, and holding information sessions with parents re healthy eating). The teachers realized that this type of change would require more time than simply one cycle of AR.

Changes in the teachers’ activity system and their ability to reach their learning goals can be attributed to the extension of their community to include university researchers and community resource people and having adequate time for professional learning to participate in ongoing sharing and reflection, something that was rarely available to them in the past. Furthermore, the study highlights the importance of having access to new tools and appropriate scaffolding to use the tools. These new tools such as inquiry-based pedagogy and the tools of AR, helped to expand the object of the teachers’ activity system. The tools also provided a means for them to expand their community such that they were able to engage in meaningful, teacher-directed professional learning. For these teachers, experiencing professional development through collaborative AR was new. With support from an extended community, time, and resources, the teachers were positioned to embed their beliefs and perspectives in classroom practice and address the contradictions in their activity system. Often, because of the situational context and personal beliefs, teachers find it challenging to adopt reform-based, inquiry-based pedagogy (Luehmann, 2007; McGinnis, Parker, & Graeber, 2004; Tillotson & Young, 2013). The approach to collaborative action research adopted in this study created the conditions needed to allow the teachers to address contradictions and to transform their thinking and classroom practice.

Activity theory has been criticized by scholars on philosophical, theoretical, and methodological grounds (Backhurst, 2009; Toomela, 2008). For example, Roschelle (1998), in a critique of the work of Nardi (1996), argued that activity theory research is not generalizable and that the theory does not always contribute to practice. Likewise, in this study, the outcomes cannot be generalized to other contexts. However, the intent of this study was to use activity theory to better understand the complex activities involved in professional learning within a particular context. Much like case study and other forms of qualitative inquiry, lessons may be learned from the particular that may be applied to similar contexts (Merriam, 1998; Stake, 1995).

Implications

This study shows how the framework of activity theory may be used to garner insight into the activity and learning of teachers, as both their activities and the context in which their work is embedded evolve and change over time (Yamagata-Lynch, 2010). While principles of effective teacher professional development have been established, knowing how to embed these in effective professional development experiences for teachers can be a challenge. This has implications for educators who plan and support teacher professional learning. Activity theory can provide a means to consider the processes and activities that make up teachers’ activity systems and the contradictions that either afford or constrain their learning goals.

In order for the teachers to address their contradictions, they needed opportunity and a range of supports which were offered through an approach to professional learning that was teacher-centered, goal-oriented, and systematic. Having this insight can better position those involved in professional development to understand the needs of teachers and how particular tools and supports (e.g., expanding teachers’ communities to include resource people) may enhance their learning. Activity theory with its focus on the social, collective, and contextual nature of learning offers a comprehensive approach to considering how to design and implement professional learning for teachers. It moves beyond a focus on the individual only and allows for consideration of how many complex factors (e.g., teachers’ beliefs and perspectives, tools, norms, community) may enhance or hinder teacher learning (Roth & Tobin, 2002).

There is a small body of research that applies CHAT to science teaching and learning. The research that examines the professional learning of primary–elementary teachers through CHAT is almost nonexistent. This study contributes to this body of literature, using activity theory to interpret and analyze how tools, an expanded community, and contradictions become sources of teacher learning and transformation. This study did not use CHAT as lens to plan the professional development program, but as a lens for data analysis. CHAT may also be adopted as a tool for teachers to self-reflect on how changes in their activity systems are contributing or thwarting their professional learning. Being aware of the complex interactions between elements in their activity system can better position teachers to make informed choice about how to effect change in their classrooms and schools.

References

Anderson, R. D. (2002). Reforming science teaching: What research says about inquiry. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 13, 1–12.

Anthony, G., Hunter, R., & Thompson, Z. (2014). Expansive learning: Lessons from one teacher’s learning journey. ZDM, 46, 279–291. doi:10.1007/s11858-013-0553-z

Backhurst, D. (2009). Reflections on activity theory. Educational Review, 61, 197–210.

Bellamy, R. K. (1996). Designing educational technology: Computer-mediated change. In B. A. Nardi (Ed.), Context and consciousness: Activity theory and human–computer interaction (pp. 123–146). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Carr, W., & Kemmis, S. (1986). Becoming critical: Education, knowledge and action research. London: Falmer.

Center for Activity Theory and Developmental Work Research. (2003–2004). The activity system. http://www.edu.helsinki.fi/activity/pages/chatanddwr/activitysystem/

Chin, C. (2007). Teacher questioning in science classrooms: Approaches that stimulate productive thinking. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 44, 815–843.

Clark, J. C., & Groves, S. (2012). Teaching primary science: Emotions, identity and the use of practical activities. The Australian Educational Researcher, 39, 463–475. doi:10.1007/s13384012-0076-6

Creswell, J. W. (2003). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Davis, E. A., Petish, D., & Smithey, J. (2006). Challenges new science teachers face. Review of Educational Research, 76, 607–651. doi:10.3102/00346543076004607

Day, C., & Sachs, J. (2004). International handbook on the continuing professional development of teachers. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Dubois, S. L., & Luft, J. A. (2014). Science teachers without classrooms of their own: A study of the phenomenon of floating. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 25, 5–23. doi:10.1007/s10972-013-9364-x

Eilks, I., & Markic, S. (2011). Effects of a long-term participatory action research project on science teachers’ professional development. EURASIA Journal of Mathematics, Science & Technology Education, 7(3), 149–160.

Engeström, Y. (1987). Learning by expanding: An activity-theoretical approach to developmental research. Helsinki: Orienta-Konsultit.

Engeström, Y. (2000). Activity theory as a framework for analyzing and redesigning work. Ergonomics, 43, 960–974. doi:10.1080/001401300409143

Engeström, Y. (2001). Expansive learning at work: Toward an activity theoretical reconceptualization. Journal of Education and Work, 14, 133–156. doi:10.1080/13639080020028747

Engeström, Y., & Miettinen, R. (1999). Introduction. In Y. Engeström, R. Miettinen, & R. L. Punamäki (Eds.), Perspectives on activity theory (pp. 1–18). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Evernote Corporation. (2015). Evernote [Web application]. Retrieved December 7, 2015 from https://evernote.com/

Fairbanks, C. M., Duffy, G. G., Faircloth, B. S., He, Y., Levin, B., Rohr, J., & Stein, C. (2010). Beyond knowledge: Exploring why some teachers are more thoughtfully adaptive than others. Journal of Teacher Education, 61(1–2), 161–171. doi:10.1177/0022487109347874

Fraser, C. A. (2010). Continuing professional development and learning in primary science classrooms. Teacher Development, 14(1), 85–106.

Garet, M. S., Porter, A. C., Desimone, L., Birman, B. F., & Yoon, K. S. (2001). What makes professional development effective? Results from a national sample of teachers. American Educational Research Journal, 38(4), 915–945. doi:10.3102/00028312038004915

Goodnough, K., Pelech, S., & Stordy, M. (2014). Effective professional development in STEM Education: The perceptions of primary/elementary teachers. Teacher Education and Practice, 27 (2–3), 402–423.

Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. (2004). Biology 3201 curriculum guide. http://www.ed.gov.nl.ca/edu/k12/curriculum/guides/science/bio3201/intro.pdf

Greenwood, D. J., & Levin, M. (2006). Introduction to action research: Social research for social change. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hanafin, J. (2014). Multiple intelligences theory, action research, and teacher professional development: The Irish MI project. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 39(4), 126–142.

Holroyd, C., & Harlen, W. (1996). Primary teachers’ confidence about teaching science and technology. Research Papers in Education, 11, 323–335. doi:10.1080/0267152960110308

Hume, A. C. (2012). Primary connections: Simulating the classroom in initial teacher education. Research in Science Education, 42, 551–565.

Jeynes, W. H. (2005). A meta-analysis of the relation of parental involvement to urban elementary school student academic achievement. Urban Education, 40(3), 237–269.

Jeynes, W. H. (2007). The relationship between parental involvement and urban secondary school student academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Urban Education, 42(1), 82–110.

Johannessen, Ø. L. (2015). Negotiating and reshaping Christian values and professional identities through action research: Experiential learning and professional development among Christian religious education teachers. Educational Action Research, 23, 331–349.

Jonassen, D. H., & Rohrer-Murphy, L. (1999). Activity theory as a framework for designing constructivist learning environments. Educational Technology Research and Development, 47(1), 61–79. doi:10.1007/BF02299477

Kaptelinin, V., & Nardi, B. A. (2006). Acting with technology: Activity theory and interaction design. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Kemmis, S., & McTaggart, R. (2005). Participatory action research: Communicative action and the public sphere. In N. K. Denzin, Y. S. Lincoln, N. K. Denzin, & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed., pp. 559–603). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kuutti, K. (1996). Activity theory as a potential framework for human-computer interaction research. In B. Nardi (Ed.), Context and consciousness: Activity theory and human–computer interaction (pp. 17–44). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Leontiev, A. A. (1981). Sign and activity. In J. Wertsch (Ed.), The concept of activity in Soviet psychology (pp. 241–255). New York: Sharpe.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry: The paradigm revolution. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Loxley, A., Johnston, K., Murchan, D., Fitzgerald, H., & Quinn, M. (2007). The role of whole-school contexts in shaping the experiences and outcomes associated with professional development. Journal of In-service Education, 33, 265–285.

Luehmann, A. L. (2007). Identity development as a lens to science teacher preparation. Science Education, 91, 822–839. doi:10.1002/sce.20209

Mak, B., & Pun, S. (2015). Cultivating a teacher community of practice for sustainable professional development: Beyond planned efforts. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 21(1), 4–21.

McGinnis, J. R., Parker, C., & Graeber, A. O. (2004). A cultural perspective of the induction of five reform-minded beginning mathematics and science teachers. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 41, 720–747. doi:10.1002/tea.20022

McIntyre, D. (2005). Bridging the gap between research and practice. Cambridge Journal of Education, 35(3), 357–382.

McNiff, J. (2013). Action research: Principles and practice. London: Routledge.

McNiff, J., & Whitehead, J. (2011). All you need to know about action research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Meiers, M., Ingvarson, L., & Beavis, A. (2005). Factors affecting the impact of professional development programs on teachers’ knowledge, practice, student outcomes & efficacy. http://research.acer.edu.au/professional_dev/1

Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mills, G. (2010). Action research: A guide for the teacher researcher. Boston: Pearson.

Minner, D. D., Levy, A. J., & Century, J. (2010). Inquiry-based science instruction-what is it and does it matter? Results from a research synthesis years 1984–2002. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 47, 474–496.

Murphy, C. (2012). The role of subject knowledge in primary prospective teachers’ approaches to teaching the topic of area. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 15, 187–206. doi:10.1007/s10857-011-9194-8

Murphy, C., Neil, P., & Beggs, J. (2007). Primary science teacher confidence revisited: Ten years on. Educational Research, 49, 415–430. doi:10.1080/00131880701717289

Murphy, E., & Rodrigues-Manzanares, M. (Eds.). (2014). Activity theory perspectives on technology in higher education. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Murray, J. (2014). Designing and implementing effective professional learning. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Nardi, B. A. (1996). Context and consciousness: Activity theory and human–computer interaction. London: MIT Press.

Newmann, F. M., King, M. B., & Youngs, P. (2000). Professional development that addresses school capacity: Lessons from urban elementary schools. American Journal of Education, 108, 259–299. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1085442

Opfer, D., & Pedder, D. V. (2011). The lost promise of teacher professional development in England. European Journal of Education, 34, 3–24. doi:10.1080/02619768.2010.534131

Roschelle, J. (1998). Activity theory: A foundation for designing learning technology? The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 7, 241–255.

Roth, W. M., & Lee, Y. J. (2007). Vygotsky’s neglected legacy: Cultural-historical activity theory. Review of Educational Research, 77(2), 186–232. doi:10.3102/0034654306298273

Roth, W. M., & Tobin, K. (2002). Redesigning an ‘urban’ teacher education program: An activity theory perspective. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 9(2), 108–131.

Savage, J. S., Fisher, J., & Birch, L. (2007). Parental influence on eating behavior: Conception to adolescence. Journal of Law and Medical Ethics, 35, 22–34. doi:10.1111/j.1748-720X.2007.00111.x

Sezen-Barrie, A., Tran, M., McDonald, S. P., & Kelly, G. J. (2014). A Cultural Historical Activity Theory perspective to understand preservice science teachers’ reflections on and tensions during a microteaching experience. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 9, 675–697.

Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22, 63–75.

Smith, D. C., & Anderson, C. W. (1999). Appropriating scientific practices and discourses with future elementary teachers. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 36, 755–776.

Stake, R. E. (1995). The art of case study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Steiner, L. (2004). Designing effective professional development experiences: What do we know. Naperville, IL: Learning Point Associates.

Stringer, E. (2013). Action research. London: Sage.

Supovitz, J. A., Mayer, D. P., & Kahle, J. B. (2000). Promoting inquiry-based instructional practice: The longitudinal impact of professional development in the context of systemic reform. Educational Policy, 14(3), 331–356. doi:10.1177/0895904800014003001

Thomas, G. P., & McRobbie, C. J. (2013). Eliciting metacognitive experiences and reflection in a year 11 chemistry classroom: An activity theory perspective. Journal of Science Education Technology, 22, 300–313. doi:10.1007/s10956-012-9394-8

Tilgner, P. J. (1990). Avoiding science in the elementary school. Science Education, 74, 421–431.

Tillotson, J. W., & Young, M.J. (2013). The IMPPACT project: A model for studying how preservice program experiences influence science teachers’ beliefs and practices. International Journal of Education in Mathematics, Science and Technology, 1(3), 148–161. http://dergipark.ulakbim.gov.tr/ijemst/article/viewFile/5000036025/5000034944

Timperley, H. (2008). Teacher professional learning and development. Geneva: International Bureau of Education. http://www.orientation94.org/uploaded/MakalatPdf/Manchurat/EdPractices_18.pdf

Toomela, A. (2008). Activity theory is a dead end for methodological thinking in cultural psychology too. Culture & Psychology, 14(3), 289–303. doi:10.1177/1354067X08088558

Trumper, R. (2006). Teaching future teachers basic astronomy concepts—Seasonal changes—At a time of reform in science education. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 43, 879–906. doi:10.1002/tea.20138

Uden, L. (2006). Activity theory for designing mobile learning. International Journal of Mobile Learning and Organisation, 1(1), 81–102. doi:10.1504/IJMLO.2007.011190

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1986). Thought and language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press (original work published in 1934).

Wilson, S. M., & Berne, J. (1999). Teacher learning and the acquisition of professional knowledge: An examination of research on contemporary professional development. Review of Research in Education, 24, 173–209. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1167270

Yamagata-Lynch, L. C. (2010). Activity systems analysis methods: Understanding complex learning environments. New York: Springer.

Yin, X., & Buck, G. A. (2015). There is another choice: An exploration of integrating formative assessment in a Chinese high school chemistry classroom through collaborative action research. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 10, 719–752.

Zembal-Saul, C., Blumenfeld, P., & Krajcik, J. (2000). Influence of guided cycles of planning, teaching, and reflection on prospective elementary teachers’ science content representations. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 37, 318–339. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2736(200004)37:4<318:AID-TEA3>3.0.CO;2-W

Zimmerman, B. S., Morgan, D. N., & Kidder-Brown, M. K. (2014). The use of conceptual and pedagogical tools as mediators of preservice teachers’ perceptions of self as writers and future teachers of writing. Action in Teacher Education, 36, 141–156.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Goodnough, K. Professional Learning of K-6 Teachers in Science Through Collaborative Action Research: An Activity Theory Analysis. J Sci Teacher Educ 27, 747–767 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10972-016-9485-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10972-016-9485-0