Abstract

Knowing the age at which the sexual orientation disparity in depression and anxiety symptoms first emerges and the early determinants of this disparity can suggest optimal timing and targets of supportive interventions. This prospective cohort study of children ages 3 to 15 (n = 417; 10.6% same-sex-attracted; 47.2% assigned female at birth) and their parents sought to determine the age at which the sexual orientation disparity in depression and anxiety symptoms first emerges and whether peer victimization and poor parental relationships mediate this disparity. Same-sex-attracted youth first demonstrated significantly higher depression symptoms at age 12 and anxiety symptoms at age 15 than exclusively other-sex-attracted youth. Age 12 peer victimization mediated the sexual orientation disparity in age 15 depression symptoms. Age 12 poor mother–child relationship mediated the sexual orientation disparity in age 15 anxiety symptoms. The findings are discussed in terms of implications for developmentally appropriate interventions against social stress during early development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The sexual orientation disparity in internalizing psychopathology – whereby individuals who report same-sex attraction experience more symptoms of depression and anxiety than individuals who report exclusively other-sex attraction – starts early in development (Gilbey et al., 2019; Marshal et al., 2013) and persists across the lifespan (Rice et al., 2019). It is unknown, however, whether this disparity is present during early childhood (Gilbey et al., 2019). Without knowing whether the sexual orientation disparity in internalizing symptoms exists in early childhood and the potential social stress mediators of this disparity across early development, the field cannot optimally time and target interventions to reduce this disparity. Using a prospective cohort study of children’s experiences of depression and anxiety symptoms starting at age 3; developmentally appropriate assessments of social stressors at ages 9, 12, and 15 (i.e., peer victimization, poor parent–child relationship quality); and assessments of gender-based sexual attractions at age 15, the present study sought to determine the age at which the sexual orientation disparity in depression and anxiety symptoms first emerges and whether disproportionate exposure to peer victimization and poor parental relationships mediates this disparity.

Studies consistently find evidence that the sexual orientation disparity in internalizing symptoms exists during childhood and adolescence (Irish et al., 2019; la Roi et al., 2016), and might increase during the transition from adolescence into young adulthood (Becker et al., 2014; Luk et al., 2018; Marshal et al., 2013; Needham, 2012; Russell & Toomey, 2012). Yet, several methodological challenges have previously prevented examining whether the sexual orientation disparity in internalizing psychopathology exists in early childhood. First, although accurate information regarding young children’s mental health must rely on informant report (Bufferd et al., 2012; Dougherty et al., 2018), existing sexual orientation disparities research relies on self-report, typically using questionnaires (Irish et al., 2019) or interviews (Jenkins & Vazsonyi, 2013). Second, because sexual attractions do not emerge until around puberty (McClintock & Herdt, 1996), and sexual identities even later (Calzo et al., 2011), researchers cannot accurately identify sexual orientation before adolescence. A prospective cohort study of childhood internalizing psychopathology with retrospective linkage of adolescent sexual orientation can overcome these existing methodological shortcomings to identify the timing of the sexual orientation disparity.

While there are no clearly established causes of sexual orientation, several variables might influence the timing of sexual orientation disclosure and internalizing psychopathology and therefore represent potential confounds in research examining the association between youth gender-based sexual orientation and internalizing psychopathology. Population-based research shows that sexual minority youth who are racial and ethnic minorities disclose their sexual orientation earlier than sexual minority youth who are White (Calzo et al., 2011). This research also shows that sexual minority women report first disclosing their sexual orientation several years later than sexual minority men (Calzo et al., 2011). Pubertal timing has also been found to be associated with age of first sexual orientation disclosure in a community sample of sexual minority adolescent youth (Grossman et al., 2014). Given that race/ethnicity, sex assigned at birth, and pubertal timing are also associated with internalizing psychopathology (Anderson & Mayes, 2010; Hayward & Sanborn, 2002), these variables might operate as possible confounders of the association between gender-based sexual orientation and youth internalizing psychopathology and should therefore be controlled to rule out potential spurious associations.

Minority stress theory suggests that the adulthood sexual orientation disparity in internalizing psychopathology is explained by sexual minorities’ disproportionate exposure to stigma-related social stressors (Meyer, 2003). For children and adolescents, stigma-based social stress primarily manifests as poor relationships with peers and parents, including bullying, conflict, and lack of support (Goldbach & Gibbs, 2017). Peer victimization and poor parental relationships are common negative social reactions to sexual minority young people (Friedman et al., 2011), often directed toward gender nonconforming appearance and mannerisms sometimes even before self-identification as a sexual minority (Li et al., 2016; Roberts et al., 2012). Evidence suggests that sexual minorities’ disproportionate exposure to these social stressors does in fact mediate the sexual orientation disparity in internalizing symptoms during adolescence (la Roi et al., 2016; Luk et al., 2018). Yet whether the sexual orientation disparity in internalizing psychopathology exists in early childhood (e.g., age 3) is unknown.

Current Study

Without prospective cohort research linking adolescent reports of gender-based sexual attraction to the prospective development of internalizing psychopathology from early childhood, the field has lacked full knowledge of the timing and determinants of this disparity. The present study takes advantage of a methodological design capable of overcoming these limitations to identify the timing and potential determinants of the sexual orientation disparity in internalizing psychopathology from early childhood. Specifically, this study utilizes a prospective cohort design from ages 3 to 15; multi-informant (i.e., parent and child) and multi-report (i.e., questionnaires and interviews) assessment of children’s internalizing psychopathology and social stress; and a developmentally appropriate assessment of gender-based attractions at age 15. Consistent with minority stress theory and research at later ages, this study hypothesizes that the sexual orientation disparity in internalizing symptoms will emerge by adolescence and be explained by greater childhood exposure to bullying and poor parental relationships among youth who report same-sex attractions compared to youth who report exclusively other-sex attractions. Also consistent with minority stress theory, this study hypothesizes that the sexual orientation disparity in internalizing symptoms will not exist at the earliest ages examined (e.g., age 3) and will be explained by disparities in bullying and poor parental relationships.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

The Stony Brook Temperament Study is a prospective cohort study examining the role of early temperament in internalizing disorders (details provided elsewhere; (Klein & Finsaas, 2017)). Eligible families lived within 20 miles of Stony Brook, New York; had a child between 3- and 4-years old with no developmental disabilities or serious medical conditions; and had at least one English-speaking biological parent. The institutional review board approved this study. Parents provided informed consent and children ages 9 and older provided assent.

Participants were assessed at ages 3, 6, 9, 12, and 15. At the age 3 assessment, 559 families entered the study and parents completed measures about their child’s internalizing psychopathology. At the age 6 assessment, an additional 50 racial/ethnic minority families were recruited, and 501 parents completed measures about their child; 488, 476, and 458 parents and youth contributed data at the ages 9, 12, and 15 assessments, respectively. Primary analyses for the current study included all youth who endorsed either same-sex or other-sex attraction at age 15 (N = 392, 46.7% female). Table 1 presents sample demographic characteristics, stratified by age 15 attraction.

Measures

Independent variable

At age 15, youth reported their romantic and sexual attractions using the 14-item Erotic Response and Orientation Scale (EROS; (Li & Hines, 2016; Storms, 1980)), which assess past-6-month same- and other-sex attractions (e.g., romantic and sexual thoughts, desires, dreams, and experiences) on a scale of 0 (not at all), 1 (about once a month), 2 (about once a week), 3 (a few times each week), and 4 (almost every day). Those youth (n = 417) who completed at least half of the EROS items were included in further analyses; missing EROS data from those who completed more than half, but not all, of the items (n = 25) were imputed (Azur et al., 2011). Scale responses were normally distributed (i.e., skewness and kurtosis < ±1) and internal consistency among the items was high (same-sex: α = 0.94; other-sex; α = 0.93). To prevent misclassification by those reporting only very occasional attractions to either sex, exclusively other-sex attracted youth (n = 348, 83.5%) were classified as those youth who scored 0 or 1 on the same-sex attraction subscale (range: 0–27) and greater than 1 on the other-sex attraction subscale (range: 0–28). Same-sex-attracted youth (n = 44, 10.6%) were classified as those youth who scored above 1 on the same-sex attraction subscale regardless of their other-sex attractions. The analytic sample for the primary analyses contained 392 youth who reported same- or other-sex attractions. Youth who reported no attractions (i.e., a score of 0 or 1 on the other-sex and same-sex attractions subscales of the EROS) (n = 25, 6.0%) were included in supplemental analyses.

Outcomes

Child internalizing psychopathology: Interviews

At ages 3 and 6, parents were interviewed with the Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA; Egger et al., 2006), a structured diagnostic interview assessing past-3-month symptoms of DSM-IV psychiatric disorders in preschoolers. Disorders included depression (major depressive disorder [MDD], dysthymic disorder, or depression not otherwise specified [NOS]) and anxiety (specific phobia, separation anxiety disorder, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder [GAD], agoraphobia, selective mutism). Past-3-month symptoms of any depression and anxiety were rated on 2- or 3-point scales and summed. Internal consistency (α) of the symptom scales at ages 3 and 6, respectively, were adequate: depression (0.72 and 0.74) and anxiety (0.83 and 0.85). To assess interrater reliability, a second rater rated audiotapes for 21 participants at age 3 and for 35 participants at age 6. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) for depression and anxiety ranged from 0.71–1.00.

At the age 9, 12, and 15 assessments, clinical psychology doctoral students and a master’s-level clinician supervised by a child psychiatrist and clinical psychologist administered the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders (K-SADS; Birmaher et al., 2009) first to the parent and then to the child. Parent and child reports for each symptom were combined into summary ratings. Internalizing disorders included depression (MDD, dysthymic disorder, depressive disorder-NOS) and anxiety (specific phobia, separation anxiety, social phobia, GAD, agoraphobia, panic, obsessive compulsive, post-traumatic stress, acute stress, anxiety disorder-NOS). Symptoms of depression (α = 0.92–0.97) and anxiety (α = 0.74–0.99) were rated as 0 (not present), 1 (subthreshold), or 2 (threshold) and summed. At age 9, the timeframe included any symptom present until that point; at ages 12 and 15, in the previous three years. To assess interrater reliability, a second rater independently rated videotapes for 74 participants at age 9 and for 25 participants at ages 12 and 15; ICCs ranged from 0.83–0.98.

Child internalizing psychopathology: Questionnaires

Current depression and anxiety symptoms were also assessed with the youth self-reported Child Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1992) and Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED; Birmaher et al., 1999) at ages 9, 12, and 15 (CDI: α = 74–0.82, SCARED: α = 0.89–0.93).

At all assessment points, mothers completed the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), either the CBCL 1.5–5 (age 3; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000) or the CBCL 6–18 (ages 6–15) (α=0.84–0.88) (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). This study used the Internalizing Problems scale. Given that the different versions of the CBCL include different items, age- and sex-based T-scores were used.

Mediators

Peer victimization

At ages 12 and 15, youth completed the 9-item peer victimization scale of the Revised Peer Experiences Questionnaire (RPEQ; Prinstein et al., 2001), which assesses frequency of overt peer and relational victimization. Internal consistency was acceptable (α = 0.85).

As a supplemental measure, at ages 9, 12 and 15, the K-SADS interviewer rated the child’s experiences with peer victimization using information from both the parent and child. This variable was dichotomized such that children were classified as bullied often or very often (1 = often bullied) or sometimes or never (0 = not often bullied).

Quality of parental relationships

At age 12, parents and youth completed the UCLA Life Stress Interview (LSI; Rudolph & Hammen, 1999), a semi-structured interview that included an assessment of past-year quality of the youth’s relationship with each parent (e.g., conflict, lack of support). At age 15, only youth completed the interview. From these interviews, a trained research assistant rated parent–child relationship quality using a scale from 1 to 5 (higher scores indicate poorer quality). A post-doctoral fellow independently rated interviews using audio-recordings at age 12 (n = 33; mother ICC = 0.57, father ICC = 0.75) and age 15 (n = 30; mother ICC = 0.81, father ICC = 0.83).

As a supplemental measure, at ages 9, 12, and 15, the K-SADS interviewer rated the quality of the parent–child relationship for each parent based on information from the parent and child. This variable was dichotomized into ratings of fair or poor (=1) versus good or excellent (=0).

Potential confounders

Potential confounding variables were derived from existing research. These variables are depicted in a directed acyclic graph (see Supplemental Fig. 1) and include race/ethnicity, sex assigned at birth, and pubertal development.

Race/ethnicity

At ages 3 and 6, parents indicated youth’s race/ethnicity.

Sex assigned at birth

At ages 3 and 6, parents indicated youth’s sex assigned at birth.

Pubertal development

At ages 9, 12, and 15, youth completed the 6-item Pubertal Development Scale (Petersen et al., 1988), which assesses the stage of development of several indicators of puberty (e.g., growth spurt, body hair) across five items using a scale from no development (=1) to completed development (=4). Items are averaged to create a summary score. If children were unable to understand a given question on any measure, an experimenter of the same gender as the participant was available to explain it further.

Analytic Plan

Analyses were conducted in SAS 9.4. First, analyses assessed differences in internalizing psychopathology between same-sex-attracted and exclusively other-sex-attracted youth at ages 3, 6, 9, 12, and 15. Standardized (i.e., z) scores were calculated for depression and anxiety symptoms from the PAPA (ages 3 and 6) and K-SADS (ages 9, 12, and 15) and then examined in independent-samples t-tests at each age. Unequal group variances were assessed and adjusted with Levene’s test and the Welch-Satterthwaite method, respectively.

Second, to further assess sexual orientation differences in internalizing psychopathology, multivariable linear regression models were performed at each age, adjusted for sex, race/ethnicity, and, starting at age 9, pubertal development. Missing covariate data were imputed (Janssen et al., 2010); missing data on the dependent variables were excluded. Analyses regressed interviewer-assessed measures of internalizing psychopathology (e.g., PAPA, K-SADS, ages 3–15) and then youth self-report measures of internalizing psychopathology (e.g., CDI, SCARED, ages 9–15) onto attraction group. Linear regression models were also run using the CBCL as a supplemental outcome (ages 3 to 15).

Third, multivariable regression models were performed to examine sexual orientation differences in peer victimization or relationship quality with one’s mother and father, adjusted for sex, race/ethnicity, and pubertal development. Linear regression models were first performed using, as the outcome, the more comprehensive measures of peer victimization (RPEQ) and parental relationship quality (LSI) (ages 12 and 15), and then logistic regression models were performed using the supplemental one-item K-SADS ratings of these social stressors (ages 9, 12, and 15).

Finally, mediation analyses were conducted within a potential outcomes framework using PROC CAUSALMED (Valeri & VanderWeele, 2013) to calculate the total, direct, and indirect effects of sexual orientation on internalizing symptoms via social stressors (Pearl, 2014; Valeri & VanderWeele, 2013; Vanderweele & Vansteelandt, 2009). Supplemental Fig. 1 illustrates the theoretical assumptions of this mediation through a directed acyclic graph. All confounders were included and effects of social stress were allowed to differ by sexual orientation (Bauer & Scheim, 2019). For each potential mediator (age 12 social stress) and outcome (age 15 internalizing psychopathology), the total effect was decomposed into the natural direct effect and natural indirect effect. Supplemental Table 1 summarizes each component.

Sensitivity analyses removed the eight exclusively same-sex-attracted youth from the sexual minority sample to compare internalizing psychopathology and social stress between bisexually attracted youth and exclusively other-sex attracted youth. Supplemental analyses compared youth who reported no attractions to exclusively other-sex-attracted youth. In sensitivity analyses with bisexual youth and supplemental analyses with non-attracted youth, mediation analyses were not conducted given the reduced sample sizes and resulting lack of power.

Results

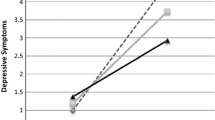

In bivariate analyses, sexual orientation differences in PAPA/K-SADS depression and anxiety symptoms became increasingly more pronounced across assessment points (see Fig. 1). In adjusted analyses, same-sex-attracted youth demonstrated higher K-SADS depression symptoms at ages 12 (β = 1.55, 95% CI = 0.40–2.71) and 15 (β = 4.67, 95% CI = 2.75–6.58) and higher K-SADS anxiety symptoms at age 15 (β = 3.06, 95% CI = 1.24–4.89). Mean estimates and confidence intervals at age 9 for K-SADS depression symptoms (95% CI = −0.33–2.01) and anxiety symptoms (95% CI = −0.50–4.00) are also consistent with a sexual orientation difference but did not reach statistical significance (see Table 2). Same-sex-attracted youth also reported elevated CDI depression symptoms at ages 12 (β = 2.87, 95% CI = 1.18–4.56) and 15 (β = 5.93, 95% CI = 4.32–7.54) and higher SCARED anxiety symptoms at ages 12 (β = 5.04, 95% CI = 1.63–8.46) and 15 (β = 8.47, 95% CI = 4.83–12.11) (see Table 2). Patterns were similar for parent-reported CBCL internalizing symptoms (see Supplemental Table 2).

Standardized scores of anxiety and depression symptoms scores measured over time by child’s gender-based attraction (same-sex vs. exclusively other-sex attraction) at age 15. Note. Depression and anxiety symptoms were assessed with the Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA) at ages 3 and 6 and the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (K-SADS) at ages 9, 12 and 15

In terms of social stressors, same-sex-attracted youth experienced higher peer victimization at ages 12 (β = 1.69, 95% CI = 0.44–2.93) and 15 (β = 2.74, 95% CI = 1.49–4.00), as assessed by the RPEQ, compared to exclusively other-sex-attracted youth. Same-sex-attracted youth also experienced more mother–child relationship discord at ages 12 (β = 0.20, 95% CI = 0.06–0.33) and 15 (β = 0.18, 95% CI = 0.04–0.33) and father–child relationship discord at age 15 (β = 0.31, 95% CI = 0.08–0.53), as assessed by the LSI (see Table 3). In supplemental analyses using the one-item KSADS rating, same-sex-attracted youth also experienced greater odds of frequent bullying than exclusively other-sex attracted youth at age 15 (aOR = 2.44, 95% CI = 1.40–4.27), with mean estimates and confidence intervals consistent with smaller, nonsignificant group differences at ages 9 (aOR = 1.41, 95% CI = 0.72–2.76) and 12 (aOR = 1.48, 95% CI = 0.82–2.68). Using the one-item K-SADS ratings of parent–child relationship quality, same-sex-attracted youth had a poorer relationship with their mother at age 12 (aOR = 1.92, 95% CI = 1.09–3.37) and both mother (aOR = 1.51, 95% CI = 0.97–2.36) and father at age 15 (aOR = 2.03, 95% CI = 1.44–2.86) compared to exclusively other-sex-attracted youth. The effect estimate and confidence interval for age 9 relationship quality with mother was consistent with a smaller, nonsignificant group difference (aOR = 1.49, 95% CI = 0.76–2.94; father: aOR = 0.94, 95% CI = 0.49–1.78).

Mediation analyses assessed the extent to which social stressors at age 12, including peer victimization and poor mother–child relationship, mediated the association between sexual orientation and internalizing symptoms at age 15 (see Table 4). Across all mediation models, same-sex attraction demonstrated a positive association with age 15 internalizing symptoms through the direct unmediated path. Age 12 peer victimization mediated the sexual orientation disparity in age 15 interviewer-assessed depression symptoms (natural indirect effect [NIE] = 1.27, 95% CI = 0.09–1.98), corresponding to almost one-third of the sexual orientation disparity in age 15 depression symptoms attributed to elevated age 12 peer victimization (percentage mediated [PM] = 26.8%, 95% CI = 1.5–66.2). Age 12 peer victimization also mediated the sexual orientation difference in: age 15 self-reported depression symptoms (NIE = 0.87, 95% CI = 0.03–2.32) corresponding to 14.7% of the total effect (95% CI = 0.2–38.4); age 15 interviewer-assessed anxiety symptoms (NIE = 0.70, 95% CI = 0.04–2.37) corresponding to 23.0% of the total effect (95% CI = −0.47–80.93); and age 15 self-reported anxiety symptoms (NIE = 1.23, 95% CI = 0.09–3.49) corresponding to 14.7% of the total effect (95% CI = 0.50–48.18).

Age 12 poor mother–child relationship mediated the sexual orientation disparity in age 15 interviewer-assessed anxiety symptoms (NIE = 0.67, 95% CI = 0.12–1.64) corresponding to 21.8% of the total effect (95% CI = 3.4–95.6). NIE estimates and 95% CIs, although they include zero, were also generally consistent with age 12 poor mother–child relationship mediating the sexual orientation disparity in age 15 self-reported depression symptoms (NIE = 0.66, 95% CI = −0.07–2.27; PM = 11.1%) and age 15 self-reported anxiety symptoms (NIE = 1.21, 95% CI = −0.06–3.81, PM = 14.4%).

The only interaction partially contributing to age 15 internalizing symptoms was between sexual orientation and age 12 peer victimization predicting interviewer-assessed depression symptoms (percentage of total effect due to interaction = 18.7%, 95% CI = −0.50–53.55).

In order to determine whether and how results applied to bisexually attracted youth specifically, sensitivity analyses removed the eight youth who reported exclusively same-sex attractions. Results showed a very similar pattern as above, when exclusively same-sex-attracted youth were included. Differences between bisexually attracted youth and exclusively other-sex-attracted youth in PAPA/K-SADS depression and anxiety symptoms became increasingly more pronounced across assessment points (see Supplemental Fig. 2). In adjusted analyses, bisexually attracted youth demonstrated higher K-SADS depression symptoms at ages 12 (β = 1.42, 95% CI = 0.18–2.67) and 15 (β = 3.89, 95% CI = 1.85–5.92) and higher K-SADS anxiety symptoms at age 15 (β = 2.51, 95% CI = 0.53–4.50). Bisexually attracted youth also reported elevated CDI depression symptoms at ages 12 (β = 2.00, 95% CI = 0.20–3.80) and 15 (β = 5.28, 95% CI = 3.57–6.99) and higher SCARED anxiety symptoms at ages 12 (β = 3.98, 95% CI = 0.27–7.70) and 15 (β = 6.57, 95% CI = 2.66–10.49). In terms of social stress, bisexually attracted youth experienced higher peer victimization at ages 12 (β = 1.43, 95% CI = 0.07–2.79) and 15 (β = 3.08, 95% CI = 1.71–4.44), as assessed by the RPEQ, compared to exclusively other-sex-attracted youth. Bisexually attracted youth also experienced more mother–child relationship discord at ages 12 (β = 0.18, 95% CI = 0.03–0.32) and marginally more mother–child relationship discord at 15 (β = 0.14, 95% CI = −0.02–0.30) and more father–child relationship discord at age 15 (β = 0.25, 95% CI = 0.01–0.49), as assessed by the LSI.

In supplemental analyses comparing youth who reported no attractions to exclusively other-sex-attracted youth, youth who reported no attractions demonstrated significantly lower KSADS depression and anxiety symptoms at age 15. They also reported significantly lower anxiety symptoms on the SCARED at age 15, but significantly higher depression symptoms on the CDI at age 9 than exclusively other-sex-attracted youth (see Supplemental Table 3). No other comparisons to exclusively other-sex-attracted youth in terms of internalizing psychopathology were significant at any age. In terms of social stress, youth who reported no attractions reported lower peer victimization on the RPEQ at age 15 and demonstrated higher mother–child relationship discord on the LSI at age 12 compared to exclusively other-sex-attracted youth (see Supplement Table 4).

Discussion

Knowing the timing and mediators of the sexual orientation disparity in internalizing psychopathology across childhood and adolescence can inform the timing and content of supportive interventions. This knowledge has been slow to accumulate given the typical lack of sexual orientation information included in prospective cohort studies from a very early age. By assessing gender-based attractions at age 15 in an ongoing prospective cohort study of internalizing psychopathology, the present study was able to determine the age at which the disparity in internalizing psychopathology became significantly different between youth reporting same-sex attractions compared to youth reporting exclusively other-sex attractions. Because this study assessed social stressors, including interviewer-based assessments of peer victimization and parent–child relationship quality, the present study was also able to determine whether these social stressors served as mediators of the sexual orientation disparity in internalizing psychopathology at the ages during which this disparity was present.

Results of this study suggest that the sexual orientation disparity in internalizing psychopathology exists by age 12 and may start taking shape earlier. Results also suggest that disparities in peer victimization (e.g., bullying) and poor parental relationships (e.g., conflict, lack of support) also exist at age 12 and perhaps earlier. Sensitivity analyses suggest that these findings apply when sexual minority youth were examined as youth reporting same-sex attractions and also when examined as youth reporting only bisexual attractions. Supporting the results of existing studies relying on self-reported social stress and internalizing symptoms (la Roi et al., 2016; Luk et al., 2018), the present results demonstrate that the age 12 disparity in peer victimization partially explained the sexual orientation disparity in age 15 depression symptoms. Further, the age 12 disparity in poor mother–child relationships also partially explained the age 15 sexual orientation disparity in anxiety symptoms.

These findings support the application of minority stress theory to the mental health of sexual minority youth. Specifically, results show evidence for a mediating role of age 12 peer victimization and poor parental relationships – two prominent minority stressors at this age (Friedman et al., 2011) – in the sexual orientation disparity in age 15 internalizing symptoms. Additionally, results show no sexual orientation disparity in internalizing psychopathology in early childhood (e.g., age 3), before disparities in stigma-based social stress exist. These findings provide evidence for the existence of minority stress in adolescence, a developmentally sensitive period during which social stress might have a particularly strong impact on mental health (e.g., Murphy et al., 2013; Romeo et al., 2006). For sexual minority youth, adolescence represents a key period of identity formation that can be adversely influenced by stigma (Russell & Fish, 2019). These findings suggest that peer victimization and poor parental relationships represent two potential ways in which stigma might influence sexual minorities’ identity formation, at the very age at which many sexual minorities first become aware of their sexual orientation (Calzo et al., 2011; Savin-Williams & Diamond, 2000). Future research is needed to study the longer-term impact of such stressors on sexual minorities’ mental health and the influence of protective buffers and identity-affirming interventions.

Supplemental analyses found a distinct pattern of results for youth who reported no attractions, compared to the pattern of results for youth reporting same-sex attractions. Specifically, youth reporting no attractions demonstrated significantly lower age 15 depression and anxiety symptoms and lower age 15 peer victimization than exclusively other-sex-attracted youth. Yet, youth reporting no attractions also demonstrated greater age 9 depression symptoms and greater age 12 poor maternal relationships. These findings contradict the scant emerging research on asexual youth, which has found that asexual youth and young adults experience greater depression and anxiety symptoms than gay and lesbian youth and young adults (Borgogna et al., 2019; McInroy et al., 2020). However, the present finding that youth reporting no attractions experienced lower peer victimization than exclusively other-sex-attracted youth partially coheres with findings of an online survey study showing that asexual youth report less discrimination than other sexual minority youth (McInroy et al., 2020). The present finding regarding greater age 12 mother–child discord for youth reporting no attractions compared to exclusively other-sex-attracted youth is novel and requires future study. Overall, these results suggest that youth who report no gender-based attractions might be at least partially protected against the mental health challenges that disproportionately affect other sexual minority youth, and even face fewer mental health challenges than heterosexual youth. These results require future study to identify the source of this protection. Because results show that these youth report less peer victimization than even heterosexual youth, the search for protective factors should include protective social experiences.

Results call for future research to identify developmentally appropriate supportive interventions before and during adolescence that can reduce the sexual orientation disparity in internalizing psychopathology. Although few interventions to reduce mental health disparities have been tested in randomized controlled trials (Chaudoir et al., 2017), several emerging intervention approaches are preliminarily promising and span structural, school, parenting, and youth domains. In terms of structural interventions, youth in US municipalities that enumerate sexual orientation in anti-bullying legislation experience less bullying, regardless of sexual orientation (Meyer et al., 2019), and sexual minority youth living in such places have lower likelihood of suicide attempt (Hatzenbuehler & Keyes, 2013). In terms of school interventions, sexual minority youth’s engagement in gender-sexuality alliances is associated with reduced mental health concerns, with increased hope operating as a potential mediator of this association (Poteat et al., 2020). In terms of family interventions, both family-based psychotherapeutic interventions (Diamond et al., 2012) and psychoeducational programs for parents of sexual minority youth (e.g., Goodman & Israel, 2020; Huebner et al., 2013) are associated with increases in parental acceptance and, in the case of attachment-based family therapy, reductions in suicidality among the sexual minority youth (Diamond et al., 2012). In terms of interventions to support sexual minority youth directly, identity-affirming cognitive-behavioral interventions for sexual minority young adults have recently shown efficacy for reducing depression and anxiety symptoms (Pachankis et al., 2021; Pachankis et al., 2020); whether a youth-adapted version of such an approach might show similar efficacy awaits future randomized controlled trials. Overall, effective interventions at this particularly sensitive developmental stage are needed to disrupt the substantial and persistent sexual orientation disparity in social stress and related psychopathology.

Results must be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, because sexual orientation cannot be reliably reported before puberty, this study relied on retrospective linkage of age 15 gender-based sexual attraction to earlier reports of psychopathology and social stress. While results demonstrated disparities using this approach, causal mediation requires a temporally antecedent predictor, not afforded by this design. Second, the mediation models tested here assume that peer and parental stressors are independent. Additional assessment periods would permit testing serial mediation, whereby for instance parental conflict predicts youth depression symptoms to predict peer victimization. Third, because the primary outcome measures were selected to be age-appropriate, they were not identical across all assessment periods. Therefore, analyses were not able to take advantage of a repeated-measures approach. Conducting separate analyses at each age might have increased Type 1 error and prevents examining latent trajectories. Fourth, while gender-based sexual attractions represent the recommended assessment of adolescent sexuality (Badgett et al., 2009), also assessing sexual identities and behaviors into young adulthood could strengthen classification of sexual orientation groups. Finally, the small sample of sexual minority youth perhaps led to the relatively wide confidence intervals around some estimates. A future larger sample would increase precision. The present results suggest that future research into the sexual orientation disparity in internalizing psychopathology would not necessarily need to focus on very young children, as the present results show no evidence of vulnerability by later sexual orientation during this developmental stage. Relatedly, while low prevalence of early childhood depression symptoms in a sample of this size might explain the lack of sexual orientation difference in depression symptoms, anxiety is common in this age group and low power is unlikely to affect this particular outcome at the youngest ages examined (Egger & Angold, 2006).

Conclusion

Given the rarity of assessments of gender-based attractions in cohort studies of young children and adolescents, the field of child and adolescent development has lacked knowledge concerning the age at which the sexual orientation disparity in depression and anxiety symptoms first emerges. By administering a measure of gender-based attractions at age 15 in a prospective cohort of youth followed from age 3, the present study was able to identify the timing of the sexual orientation disparity in depression and anxiety symptoms and whether social stressors, namely peer victimization and poor parent–child relationship quality, mediated this disparity. Findings demonstrated that same-sex-attracted youth first exhibited significantly higher depression symptoms than exclusively other-sex-attracted youth at age 12 and higher anxiety symptoms at age 15. Age 12 peer victimization mediated the sexual orientation disparity in age 15 depression symptoms. Age 12 poor mother–child relationship mediated the sexual orientation disparity in age 15 anxiety symptoms. Findings were similar when the sexual minority sample was limited to bisexually attracted youth. Compared to exclusively other-sex-attracted youth, those youth who reported no attractions exhibited lower depression and anxiety symptoms at age 15 and lower peer victimization at age 15, but more depression symptoms at age 9 and poorer mother–child relationship quality at age 12. These findings call for supportive structural (e.g., inclusive anti-bullying policies), school (e.g., gender-sexuality alliances), family (e.g., family-based psychotherapy and psychoeducation), and individual (e.g., identity-affirming cognitive-behavioral therapy) interventions to be delivered before and during adolescence to reduce the sizeable disparity in internalizing psychopathology that starts in adolescence and largely persists across the lifespan.

References

Achenbach, T., & Rescorla, L. (2001). Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment.

Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2000). Manual for the ASEBA Preschool Forms & Profiles. Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment.

Anderson, E. R., & Mayes, L. C. (2010). Race/ethnicity and internalizing disorders in youth: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(3), 338–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.12.008

Azur, M. J., Stuart, E. A., Frangakis, C., & Leaf, P. J. (2011). Multiple imputation by chained equations: What is it and how does it work? Interational Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 20(1), 40–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.329.

Badgett, L. M., Goldberg, A., Conron, K., & Gates, G. (2009). Best Practices for Asking Questions about Sexual Orientation on Surveys (SMART). https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/smart-so-survey/

Bauer, G. R., & Scheim, A. I. (2019). Methods for analytic intercategorical intersectionality in quantitative research: Discrimination as a mediator of health inequalities. Social Science & Medicine, 226, 236–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.12.015.

Becker, M., Cortina, K. S., Tsai, Y. M., & Eccles, J. S. (2014). Sexual orientation, psychological well-being, and mental health: A longitudinal analysis from adolescence to young adulthood. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1(2), 132–145. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000038.

Birmaher, B., Brent, D. A., Chiappetta, L., Bridge, J., Monga, S., & Baugher, M. (1999). Psychometric properties of the screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders (SCARED): A replication study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 38(10), 1230–1236. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199910000-00011.

Birmaher, B., Ehmann, M., Axelson, D. A., Goldstein, B. I., Monk, K., Kalas, C., Kupfer, D., Gill, M. K., Leibenluft, E., Bridge, J., Guyer, A., Egger, H. L., & Brent, D. A. (2009). Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children (K-SADS-PL) for the assessment of preschool children – A preliminary psychometric study. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 43(7), 680–686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.10.003.

Borgogna, N. C., McDermott, R. C., Aita, S. L., & Kridel, M. M. (2019). Anxiety and depression across gender and sexual minorities: Implications for transgender, gender nonconforming, pansexual, demisexual, asexual, queer, and questioning individuals. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 6(1), 54–63. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000306.

Bufferd, S. J., Dougherty, L. R., Carlson, G. A., Rose, S., & Klein, D. N. (2012). Psychiatric disorders in preschoolers: continuity from ages 3 to 6. American Journal of Psychiatry, 169(11), 1157–1164. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12020268.

Calzo, J. P., Antonucci, T. C., Mays, V. M., & Cochran, S. D. (2011). Retrospective recall of sexual orientation identity development among gay, lesbian, and bisexual adults. Developmental Psychology, 47(6), 1658–1673. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025508.

Chaudoir, S. R., Wang, K., & Pachankis, J. E. (2017). What reduces sexual minority stress? A review of the intervention “toolkit”. Journal of Social Issues, 73(3), 586–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12233.

Diamond, G. M., Diamond, G. S., Levy, S., Closs, C., Ladipo, T., & Siqueland, L. (2012). Attachment-based family therapy for suicidal lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents: A treatment development study and open trial with preliminary findings. Psychotherapy, 49(1), 62–71. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026247.

Dougherty, L. R., Klein, D. N., & Olino, T. M. (2018). Depression in children and adolescents. In J. Hunsley & E. J. Mash (Eds.), A Guide to Assessments that Work (2nd ed., pp. 99–130). Oxford University Press.

Egger, H. L., & Angold, A. (2006). Common emotional and behavioral disorders in preschool children: presentation, nosology, and epidemiology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(3-4), 313–337. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01618.x.

Egger, H. L., Erkanli, A., Keeler, G., Potts, E., Walter, B. K., & Angold, A. (2006). Test-retest reliability of the Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 45(5), 538–549. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000205705.71194.b8.

Friedman, M. S., Marshal, M. P., Guadamuz, T. E., Wei, C., Wong, C. F., Saewyc, E., & Stall, R. (2011). A meta-analysis of disparities in childhood sexual abuse, parental physical abuse, and peer victimization among sexual minority and sexual nonminority individuals. American Journal of Public Health, 101(8), 1481–1494. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.190009.

Gilbey, D., Mahfouda, S., Ohan, J., Lin, A., & Perry, Y. (2019). Trajectories of mental health difficulties in young people who are attracted to the same gender: A systematic review. Adolescent Research Review, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-019-00128-8

Goldbach, J. T., & Gibbs, J. J. (2017). A developmentally informed adaptation of minority stress for sexual minority adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 55, 36–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.12.007.

Goodman, J. A., & Israel, T. (2020). An online intervention to promote predictors of supportive parenting for sexual minority youth. Journal of Family Psychology, 34(1), 90–100. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000614.

Grossman, A. H., Foss, A. H., & D’Augelli, A. R. (2014). Puberty: Maturation, timing and adjustment, and sexual identity developmental milestones among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Journal of LGBT Youth, 11(2), 107–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2014.846068.

Hatzenbuehler, M. L., & Keyes, K. M. (2013). Inclusive anti-bullying policies and reduced risk of suicide attempts in lesbian and gay youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(1, Supplement), S21–S26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.08.010.

Hayward, C., & Sanborn, K. (2002). Puberty and the emergence of gender differences in psychopathology. Journal of Adolescent Health, 30(4), 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00336-1.

Huebner, D. M., Rullo, J. E., Thoma, B. C., McGarrity, L. A., & Mackenzie, J. (2013). Piloting lead with love: A film-based intervention to improve parents’ responses to their lesbian, gay, and bisexual children. Journal of Primary Prevention, 34(5), 359–369. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-013-0319-y.

Irish, M., Solmi, F., Mars, B., King, M., Lewis, G., Pearson, R. M., Pitman, A., Rowe, S., Srinivasan, R., & Lewis, G. (2019). Depression and self-harm from adolescence to young adulthood in sexual minorities compared with heterosexuals in the UK: a population-based cohort study. The Lancet Child and Adolescent Health, 3(2), 91–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30343-2.

Janssen, K. J., Donders, A. R. T., Harrell, Jr, F. E., Vergouwe, Y., Chen, Q., Grobbee, D. E., & Moons, K. G. (2010). Missing covariate data in medical research: To impute is better than to ignore. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 63(7), 721–727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.12.008.

Jenkins, D. D., & Vazsonyi, A. T. (2013). Psychosocial adjustment during the transition from adolescence to young adulthood: Developmental evidence from sexual minority and heterosexual youth. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 8(3), 181–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2013.777764.

Klein, D. N., & Finsaas, M. C. (2017). The Stony Brook temperament study: Early antecedents and pathways to emotional disorders. Child Development Perspectives, 11(4), 257–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12242.

Kovacs, M. (1992). Children’s Depression Inventory Manual. M.-H. Systems.

la Roi, C., Kretschmer, T., Dijkstra, J. K., Veenstra, R., & Oldehinkel, A. J. (2016). Disparities in depressive symptoms between heterosexual and lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth in a Dutch cohort: The TRAILS study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(3), 440–456. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-015-0403-0.

Li, G., & Hines, M. (2016). In search of emerging same-sex sexuality: Romantic attractions at age 13 years. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(7), 1839–1849. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0726-2.

Li, G., Pollitt, A. M., & Russell, S. T. (2016). Depression and sexual orientation during young adulthood: Diversity among sexual minority subgroups and the role of gender nonconformity. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(3), 697–711. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0515-3.

Luk, J. W., Sita, K. R., Gilman, S. E., Goldstein, R. B., Haynie, D. L., & Simons-Morton, B. G. (2018). Adolescent sexual orientation and developmental transition in emerging adulthood: Disparities in school, work, residence, and transportation. Journal of Adolescent Health, 63(5), 649–651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.05.027.

Marshal, M. P., Dermody, S. S., Cheong, J., Burton, C. M., Friedman, M. S., Aranda, F., & Hughes, T. L. (2013). Trajectories of depressive symptoms and suicidality among heterosexual and sexual minority youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(8), 1243–1256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-013-9970-0.

McClintock, M. K., & Herdt, G. (1996). Rethinking puberty: The development of sexual attraction. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 5(6), 178–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.ep11512422.

McInroy, L. B., Beaujolais, B., Leung, V. W. Y., Craig, S. L., Eaton, A. D., & Austin, A. (2020). Comparing asexual and non-asexual sexual minority adolescents and young adults: Stressors, suicidality and mental and behavioural health risk outcomes. Psychology & Sexuality, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2020.1806103

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674.

Meyer, I. H., Luo, F., Wilson, B. D. M., & Stone, D. M. (2019). Sexual orientation enumeration in state antibullying statutes in the United States: Associations with bullying, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts among youth. LGBT Health, 6(1), 9–14. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2018.0194.

Murphy, M. L. M., Slavich, G. M., Rohleder, N., & Miller, G. E. (2013). Targeted rejection triggers differential pro- and anti-inflammatory gene expression in adolescents as a function of social status. Clinical Psychological Science, 1(1), 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702612455743.

Needham, B. L. (2012). Sexual attraction and trajectories of mental health and substance use during the transition from adolescence to adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41(2), 179–190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-011-9729-4.

Pachankis, J. E., Harkness, A., Behari, K., Clark, K. A., McConocha, E. M., Winston, R., Adeyinka, O., Maciejewski, K., Reynolds, J., Bränström, R., Esserman, D. A., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., & Safren, S. A. (2021). LGBTQ-affirmative cognitive-behavioral therapy for young gay and bisexual men’s mental and sexual health: A three-arm randomized controlled trial [Unpublished manuscript]. School of Public Health, Yale University.

Pachankis, J. E., McConocha, E. M., Clark, K. A., Wang, K., Behari, K., Fetzner, B. K., Brisbin, C. D., Scheer, J. R., & Lehavot, K. (2020). A transdiagnostic minority stress intervention for gender diverse sexual minority women’s depression, anxiety, and unhealthy alcohol use: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88(7), 613–630. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000508.

Pearl, J. (2014). Interpretation and identification of causal mediation. Psychological Methods, 19(4), 459–481. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036434.

Petersen, A. C., Crockett, L., Richards, M., & Boxer, A. (1988). A self-report measure of pubertal status: Reliability, validity, and initial norms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 17(2), 117–133. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01537962.

Poteat, V. P., Rivers, I., & Vecho, O. (2020). Membership experiences in gender-sexuality alliances (GSAs) predict increased hope and attenuate the effects of victimization. Journal of School Psychology, 79, 16–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2020.02.001.

Prinstein, M. J., Boergers, J., & Vernberg, E. M. (2001). Overt and relational aggression in adolescents: Social-psychological adjustment of aggressors and victims. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 30(4), 479–491. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15374424JCCP3004_05.

Rice, C. E., Vasilenko, S. A., Fish, J. N., & Lanza, S. T. (2019). Sexual minority health disparities: An examination of age-related trends across adulthood in a national cross-sectional sample. Annals of Epidemiology, 31, 20–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2019.01.001.

Roberts, A. L., Rosario, M., Corliss, H. L., Koenen, K. C., & Austin, S. B. (2012). Elevated risk of posttraumatic stress in sexual minority youths: mediation by childhood abuse and gender nonconformity. American Journal of Public Health, 102(8), 1587–1593. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300530.

Romeo, R. D., Bellani, R., Karatsoreos, I. N., Chhua, N., Vernov, M., Conrad, C. D., & McEwen, B. S. (2006). Stress history and pubertal development interact to shape hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis plasticity. Endocrinology, 147(4), 1664–1674. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2005-1432.

Rudolph, K. D., & Hammen, C. (1999). Age and gender as determinants of stress exposure, generation, and reactions in youngsters: a transactional perspective. Child Development, 70(3), 660–677. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00048.

Russell, S. T., & Fish, J. N. (2019). Sexual minority youth, social change, and health: A developmental collision. Research in Human Development, 16(1), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427609.2018.1537772.

Russell, S. T., & Toomey, R. B. (2012). Men’s sexual orientation and suicide: evidence for U.S. adolescent-specific risk. Social Science & Medicine, 74(4), 523–529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.038.

Savin-Williams, R. C., & Diamond, L. M. (2000). Sexual identity trajectories among sexual-minority youths: Gender comparisons. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 29(6), 607–627. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1002058505138.

Storms, M. D. (1980). Theories of sexual orientation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38(5), 783–792. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.38.5.783.

Valeri, L., & VanderWeele, T. J. (2013). Mediation analysis allowing for exposure–mediator interactions and causal interpretation: theoretical assumptions and implementation with SAS and SPSS macros. Psychological Methods, 18(2), 137 https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031034.

Vanderweele, T. J., & Vansteelandt, S. (2009). Conceptual issues concerning mediation, interventions and composition. Statistics and its Interface, 2(4), 457–468. https://doi.org/10.4310/SII.2009.v2.n4.a7.

Authors’ Contributions

JP conceptualized and designed the current study, drafted the manuscript, reviewed and supervised data analyses; KC conducted the data analyses, drafted the manuscript, reviewed and revised the manuscript; DK conceptualized and designed the Stony Brook Temperament Study, coordinated and supervised data collection, critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content; LD conceptualized and designed the current study, drafted the manuscript, reviewed and supervised data analyses. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

All phases of this study were supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH069942). Data analyses and manuscript preparation were supported by the David R. Kessler, MD ’55 Fund for LGBTQ Mental Health Research at Yale. The National Institute of Mental Health (K01MH125073) supported a portion of Kirsty Clark’s effort on the data analyses and manuscript preparation. The study funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study.

Data Sharing and Declaration

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

The Stony Brook University institutional review board approved this human subjects study.

Informed Consent

Parents provided informed consent and children ages 9 and older provided assent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pachankis, J.E., Clark, K.A., Klein, D.N. et al. Early Timing and Determinants of the Sexual Orientation Disparity in Internalizing Psychopathology: A Prospective Cohort Study from Ages 3 to 15. J Youth Adolescence 51, 458–470 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-021-01532-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-021-01532-x