Abstract

Social dominance goals represent desires to be powerful and prominent among peers. Previous studies have documented that endorsing social dominance goals is positively associated with bullying behavior. However, little is known about how classroom context moderates the social dominance goals–bullying association. The present study examined the role of classroom status hierarchy in the longitudinal association between social dominance goals and bullying in a sample of 1,603 children attending 17 grade 3 classrooms (n = 558, 46.2% girls, Mage = 9.33 years, SD = 0.44), 15 grade 4 classrooms (n = 491, 45.0% girls, Mage = 10.31 years, SD = 0.38) and 16 grade 7 classrooms (n = 554, 49.3% girls, Mage = 13.2 years, SD = 0.46) in China, followed for 1 year. Classroom peer status hierarchy was assessed by the within-classroom standard deviation in perceived popularity. Social dominance goals were obtained through self-reports. Bullying was measured via peer nomination. The multilevel models revealed that social dominance goals at Wave 1 predicted increases in bullying at Wave 2 only in classrooms with higher status hierarchies, after controlling for gender, grade, classroom size, and classroom gender distribution. These findings indicate that children who strive for social dominance goals are more likely to bully others when power is less equally distributed in the classroom.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

From an evolutionary perspective (Pellegrini 2002; Salmivalli and Peets 2008), most bullying behaviors are goal-oriented and motivated by a desire for social dominance, that is a desire for high status, influence, and visibility among peers. There is indeed evidence that those who endorse social dominance goals are more likely to engage in bullying behavior (Caravita and Cillessen 2012; Olthof et al. 2011; Sijtsema et al. 2009). As goals and goal-concordant behaviors could be activated and aroused by social contexts (Lindenberg 2013), it is critical to understand the role of context in the association between social dominance goals and bullying, defined as repeated aggression against a more vulnerable peer (Olweus 2013). Classroom status hierarchy is a possible contextual factor that moderates this association (Garandeau et al. 2011). A clear status hierarchy, which reflects strong classroom inequalities in social status, might promote bullying behavior among social dominance-oriented children by making bullying more socially rewarding and mitigating risks of physical hurt and social costs (Reijntjes et al. 2013). Using a 1-year longitudinal design, the present study examines the moderating role of classroom status hierarchy in the prospective association between social dominance goals and bullying behavior with a large Chinese sample.

Social Dominance Goals and Bullying

Social dominance goals refer to desires to be powerful and prominent among peers (Jarvinen and Nicholls 1996; Kiefer and Ryan 2008). An evolutionary approach has identified bullying behavior as a strategy to establish and maintain social dominance within the group (Hawley 1999; Volk et al. 2012) and empirical evidence shows that this strategy can be effective (e.g., Reijntjes et al. 2013). By picking on more vulnerable peers, bullies can induce obedience and feelings of fear in their peers (Volk et al. 2012), and further consolidate their dominant position in the peer group (Pellegrini and Long 2002). Therefore, children who are oriented to social dominance are inclined to display bullying.

The positive association between dominance-like goals and bullying among children and adolescents has been reported by a substantial body of studies. For example, a cross-sectional study reported that the endorsement of agentic goals (i.e., aims toward power, mastery, and status) was positively associated with bullying in middle childhood and early adolescence, especially for children who were perceived as popular in the classroom (Caravita and Cillessen 2012). Moreover, using a dyadic approach, a study found that adolescents’ probability of being a bully in bully-victim dyads was related to a high level of agentic goals (Sijtsema et al. 2009). Furthermore, another study found that bullies reported more desire to gain power, dominance, and prestige than their peers in early adolescence (Olthof et al. 2011).

Classroom Status Hierarchy and the Social Dominance Goals–Bullying Association

Social dominance goals alone are likely insufficient to explain bullying behavior. According to the goal-framing theory (Lindenberg 2013), individuals become more sensitive to the information about opportunities to realize their goals when their specific goals are activated. Children who view social dominance as their major goal will pay special attention to the potential benefits and costs of bullying behavior in the social contexts in which they find themselves (Pouwels et al. 2019), as such behavior is their customary means of attaining dominance. If they detect the cues that bullying may facilitate the realization of their goals, at minimal costs for themselves, they are more likely to engage in bullying (Veenstra et al. 2007). Thus, it is important to investigate how contextual factors influence the association between social dominance goals and bullying behavior.

Social status hierarchy is a pervasive and fundamental feature of social organization in human groups (Halevy et al. 2011). In classroom settings, status hierarchy has been generally operationalized as the standard deviation in perceived popularity among the students in a classroom (Garandeau et al. 2011; Zwaan et al. 2013). As perceived popularity reflects power, dominance, and visibility among peers (Cillessen and Marks 2011), classroom status hierarchy represents the distribution of power and dominance in the classroom. In classrooms with high levels of status hierarchy, only few students are perceived as “popular” and hold the power in the classroom, while in low-hierarchy classrooms, children’s social status is relatively egalitarian. A longitudinal study found that a high level of status hierarchy predicted increases in bullying 6 months later in a sample of 11,296 adolescents from 583 classes in Finland (Garandeau et al. 2014).

Highly hierarchical contexts may encourage children who strive for social dominance to engage in bullying, because such contexts might make it more likely that bullying behaviors are rewarded with social benefits in the form of high popularity. Consistent with this proposition, several cross-sectional studies have found that in middle childhood the association between aggression and popularity was stronger in hierarchical classrooms where a small number of students play a prominent role in interpersonal connections (Ahn et al. 2010), and where levels of perceived popularity vary considerably across students (Garandeau et al. 2011, but see Zwaan et al. 2013). Similarly, a recent longitudinal study revealed that higher levels of classroom status hierarchy led to higher aggression–popularity norms in the classroom (i.e., stronger positive within-classroom association between bullying and popularity) during adolescence (Laninga-Wijnen et al. 2019). Furthermore, dominance positions are scarce and valuable in highly hierarchical classrooms (Garandeau et al. 2014). The popular children in such classrooms possess more power and visibility than in the classrooms where social status is more equally distributed. The salient reputational rewards attached to bullying in such social environments should increase the accessibility of social dominance goals, thereby facilitating and reinforcing the bullying behavior of children who desire dominance (Custers and Aarts 2010).

In addition to bringing social benefits to bullying children, hierarchical classrooms might also reduce the costs of bullying. The potential costs of bullying, such as physical harm and loss of social approval, might often inhibit the motivation to bully others (Veenstra et al. 2007). However, victimized children are more likely to be unpopular and rejected in highly hierarchical classrooms (Ahn et al. 2010). Due to their low status, victims are less likely to resist or receive protection from other peers when being bullied (Huitsing et al. 2014). Therefore, children who endorse social dominance goals may pick on these easy targets to gain dominance at a low cost (Sijtsema et al. 2009).

Taken together, the above findings suggest that classroom status hierarchy may relate to higher benefits and lower costs for bullying behaviors. In classrooms of higher status hierarchy, dominance-hungry children may be more motivated to engage in bullying behavior due to the clear social rewards of bullying and the victims’ higher vulnerability. However, to date, no study has investigated the role of classroom status hierarchy in the association between social dominance goals and bullying. Therefore, the present study tests whether it has a moderating effect on social dominance goals–bullying associations.

Other Possible Moderators of Social Dominance Goals–Bullying Associations

Individual- and classroom-level demographic factors are suspected to be predictive of the association between social dominance goals and bullying behavior (e.g., Caravita and Cillessen 2012). Therefore, the current study examined the moderating effects of gender, grade, classroom size, and classroom gender distribution.

Gender

Gender is an important factor to consider when examining the association between social dominance goals and bullying behavior (Rose and Rudolph 2006). Bullying, especially physical bullying, was more common in boys (Smith et al. 2019). In China, both physical and relational bullying were more prevalent among boys (Zhang et al. 2016), as collectivistic cultures may inhibit the use of physical aggression but facilitate relational aggression for both genders (Chen et al. 2019). Moreover, bullying is more likely to be rewarded with status among boys than among girls (de Bruyn et al. 2010; Caravita and Cillessen 2012). Therefore, boys are more likely to regard bullying as an effective approach to obtain social dominance (Rose and Rudolph 2006). Compared to girls, boys who endorse social dominance goals are more likely to engage in physical aggression (Kiefer and Wang 2016; Ojanen et al. 2012) and less likely to follow school rules (Kiefer and Ryan 2008). Therefore, boys who endorse social dominance goals are more likely than girls to engage in bullying.

Grade

The association of social dominance goals with bullying behavior may be different in middle childhood and in early adolescence. Along with the developmental transition from childhood to adolescence, children transit from elementary schools to secondary schools. During the re-establishment of dominance in a new, larger social system (Pellegrini and Long 2002), both endorsement of social dominance goals and bullying behavior tend to increase (LaFontana and Cillessen 2010). Furthermore, bullying is increasingly reinforced by social rewards in peer interactions from middle childhood to early adolescence (Caravita and Cillessen 2012; Cillessen and Mayeux 2004; Garandeau et al. 2011). These findings led us to expect that children who strive more for social dominance might be more likely to bully others in early adolescence than in middle childhood. However, a study found that the correlation coefficients between agentic goals and bullying in middle childhood and early adolescence were 0.06 and 0.09, respectively, which indicated that differences across age groups were not significant, according to Fisher’s r-to-Z comparison (Caravita and Cillessen 2012). To compare the social dominance goals–bullying association in middle childhood and in early adolescence, potential grade differences were examined using third-, fourth- and seventh-graders.

Classroom size

Classroom size, referring to the number of students in a classroom, is related to classroom bullying rates. There is often a higher prevalence of bullying in smaller classrooms (e.g., Garandeau et al. 2014, 2019). Besides, the link between bullying and popularity may be stronger in smaller classrooms than in larger classrooms (Garandeau et al. 2019, the Austrian sample; but see Garandeau et al. 2019, the Dutch sample). As bullying may bring more social rewards in smaller classrooms, children who strive for social dominance might be more likely to bully others in such contexts. Therefore, this study explored whether classroom size moderated social dominance goals–bullying association in the present study.

Classroom gender distribution

Classroom gender distribution might be associated with class norms related to bullying. Due to its higher normativeness among boys (Caravita and Cillessen 2012; Smith et al. 2019), bullying is more likely to be reinforced, and less likely to be punished by peers in classrooms with a higher proportion of boys (Laninga-Wijnen et al. 2020). Partly supporting this notion, a study found that a high ratio of boys in the classroom strengthened the popularity–aggression association among boys (Zwaan et al. 2013). Given that the unbalanced classroom gender distribution is assumed to promote gender-specific behavior (Kuppens et al. 2008), there was a reason to expect that social dominance goals predict increases in bullying especially in classrooms with a higher proportion of boys.

Cultural consideration

Chinese culture is characterized as vertical-collectivistic with emphasis on both interdependence and hierarchy among peers (Schwartz et al. 2010; Triandis 1995). One the one hand, due to the significance of interdependence, Chinese children can be more concerned with establishing harmonious peer relationships than acquiring social dominance in the classroom (Wright et al. 2014). Moreover, bullying behavior is highly discouraged in Chinese culture, because it may threaten group cohesion (Chen et al. 2019). Accordingly, bullies are more likely to be unpopular and be rejected by peers (Ji et al. 2016). One the other hand, Chinese classrooms are hierarchical in terms of status, as teachers formally appoint specific children to leadership positions (Schwartz et al. 2010). Reflecting the vertical feature in collectivism, each group member has a clear position in the social hierarchy and is willing to sacrifice their own interests for the collective well-being (Chen et al. 2018; Schwartz et al. 2010). As such, victimizing low-status students could be recognized as a legitimate means to maintain social order and reinforce their roles in the group (Schwartz et al. 2010), especially in the classroom with clear hierarchy. Therefore, the Chinese cultural context provides an ideal setting for testing the function of classroom status hierarchy.

Current Study

Although the association between social dominance goals and bullying is well established in the extant literature, much remains unknown about how the classroom context affects the extent to which the pursuit of social dominance translates into bullying behavior (Kiefer and Ryan 2008). In the current 1-year longitudinal study, a large sample of more than 1600 Chinese students in middle childhood (grade 3 and grade 4) and early adolescence (grade 7) from 41 classrooms was recruited to examine how classroom hierarchy moderated the associations between social dominance goals and bullying behavior. The central hypothesis of this study was that the association between social dominance goals and bullying was stronger in classrooms with higher levels of status hierarchy. In addition, gender, grade, classroom size and classroom gender distribution are included as possible moderators of social dominance goals–bullying association. The hypotheses were as follows: (1) boys and older children who desire social dominance will be more likely to engage in bullying; (2) the association between social dominance goals and bullying will be stronger in the classrooms with fewer students and higher proportion of boys.

Method

Participants and Procedures

At Wave 1, participants were 1,603 children from in grade 3 (n = 558, 46.2% girls, Mage = 9.33 years, SD = 0.44), grade 4 (n = 491, 45.0% girls, Mage = 10.31 years, SD = 0.38) and grade 7 (n = 554, 49.3% girls, Mage = 13.2 years, SD = 0.46), recruited from 41 classrooms (including 17 grade 3 classrooms, 15 grade 4 classrooms and 16 grade 7 classrooms) in 1 elementary school, 1 secondary school and 3 combined schools (comprising both elementary and secondary school grades) in Jinan and Tai’an, PR China. Nearly all of the participants were Han Chinese ethnicity (the vast majority ethnic group in China, at 92% of total population) and native Mandarin speakers (the majority language in China, at 70% of total population). In the original sample, 89.9% of mothers and 91.3% of fathers had an educational attainment of senior high school degree or higher. In China, students take almost all their lessons with same classmates during an academic year, in both elementary and secondary schools. The schedule of courses and other activities is typically identical for all students in the same class.

Data were collected in the 3rd month of the spring semester (i.e., May). Prior to data collection, researchers sent consent letters to students, parents, teachers and school principals, in which the research aims and procedures were described briefly. The children involved were offered a gift (about $1). Through these procedures, 94.5% of the children contacted for the study both received parental permission to participate and gave their assent. The participants completed a battery of self-report measures regarding their social goals and peer nominations regarding bullying and social status during a single class period in schools. There were also other measures not utilized in the present study. To ensure confidentiality and anonymity, everyone also received a list of their classmates with their corresponding three-digit numbers. These numbers were used to respond to the peer nomination questions, so no names were presented in the questionnaires. Answering the questionnaires took ~40 min. During the surveys, school teachers were not present. The research design and procedure were reviewed and approved by the Human Subjects Research Ethics Committee in the department of psychology in the first author’s university.

Measures

Given that all the measures were originally developed in English, a standard translation and back-translation procedure was used to ensure equivalence of all the measures between the original English version and the Chinese translation. This consisted of first translating the scale from English into Chinese and then from Chinese back into English and finally evaluating the level of agreement between the original and back-translated English versions. Two bilingual (English and Chinese) professors in developmental psychology and a professional translator carried out the process.

Demographic variables

Demographic characteristics, including gender, grade and class, were reported by the children themselves. Gender was dummy-coded as 0 = girl and 1 = boy, and grade was dummy-coded as 0 = grade 3 and grade 4, and 1 = grade 7.

Bullying

Bullying was assessed with the bullying subscale from the Participant Role Questionnaire (Salmivalli and Voeten 2004). To begin with, the research assistants gave the participants a definition of bullying, which highlighted its intentionality, repetition and the power imbalance. Then, children were asked to nominate up to three classmates who fit the description in three items about bullying: “Starts bullying”, “Makes the others join in the bullying”, and “Always finds new ways of harassing the victim” (Salmivalli and Voeten 2004). Given that Chinese students take almost all their lessons only with the students from their own classroom, nominations were limited to classmates only. For each item, a proportion score was calculated for each child by dividing the number of raw nominations by the number of nominators within each classroom (Garandeau et al. 2014). Scores for each item ranged from 0 (no nominations) to 1 (nominated by all classmates). The three items’ scores were averaged to calculate bullying scores, with a higher score indicating more bullying behavior. The Cronbach’s α for peer-reported bullying was 0.97 at both waves.

Social dominance goals

Social dominance goals were assessed via three items from the Social Goals Questionnaire (Jarvinen and Nicholls 1996; Kiefer and Ryan 2008). One item from the original scales was excluded as it lowered the reliability of the scale in this study (i.e., “When I am with people my own age, I like it when I make them do what I want”). For each item, participants were asked to respond to items on a five-point scale (e.g., “When I’m with people my own age I like it when they worry that I’ll hurt them”; 1 = not at all true of me, 5 = really true of me). Scores for subscale items were averaged to create the social dominance goals measure, with a higher score indicating higher endorsement of social dominance goals. The Cronbach’s α for social dominance goals at Wave 1 was 0.70.

Classroom size

Classroom size was the number of students in a classroom.

Classroom gender distribution

Classroom gender distribution was indicated by class proportion of boys, i.e., dividing the number of boys by the number of students in a classroom.

Classroom status hierarchy

The level of classroom status hierarchy was measured by the standard deviation of individual perceived popularity scores within a classroom (Garandeau et al. 2011; Zwaan et al. 2013). For perceived popularity, participants received a roster of all consenting students in their classroom and were asked to indicate “Who is the most popular one in your classroom”. Following previous studies (Li et al. 2012; Tseng et al. 2013), the Chinese term “shou huan ying” (受欢迎) was used to represent popularity in this study. Because this Chinese term may not have the exact same meaning as the English term (Niu et al. 2016), the research assistants further explained to participants that the popular students refer to the “super stars” in their classrooms. Through this approach, it is expected that participants nominated the classmates with the highest visibility among peers. Perceived popularity was indicated by a proportion score, which was created by dividing the total number of nominations a student received by the number of nominators within each classroom. The standard deviation of the proportion score of popularity was computed within each classroom to reflect classroom status hierarchy. A large standard deviation of perceived popularity within the classroom indicates a higher degree of classroom status hierarchy (Garandeau et al. 2011).

Data Analyses

To test the hypotheses, several multilevel models were employed. Bullying at Wave 2 served as the outcome variable in the different models. Individual-level predictors included Wave 1 bullying, gender and social dominance goals. Individual-level continuous variables were centered at the classroom mean. Gender was weighted-effects-coded as boy = 0.48 and girl = −0.52, to ensure that the values for gender added up to 0 (te Grotenhuis et al. 2017) for all participants. To explore gender differences in the social dominance goals–bullying association, the gender × social dominance goals interaction was included as an individual-level factor. Classroom-level predictors, including grade, size, proportion of boys and status hierarchy, were centered at the grand mean.

Data analyses included three stages. First, an unconditional model was conducted without any individual- or classroom-level predictors to obtain intraclass correlation (ICC, the proportion of total variance that is between classrooms) of bullying behavior. Second, individual-level predictors were added into the unconditional model to test the prospective association between social dominance goals and bullying and its gender differences. Third, to test whether the association between social dominance goals and bullying varied between classrooms as function of grade, class size, classroom proportion of boys and classroom status hierarchy, classroom-level predictors and cross-level interactions were added to the models. All Models were estimated using Mplus 7.0 (Muthén and Muthén 2012).

Results

Missing Data

At the second wave, a total of 125 children (7.8%) dropped out because of hectic schedules and transferring to a new school. The percentages of missing data for social dominance goals, bullying at Wave 1 and bullying at Wave 2 were 0.0%, 1.7% and 7.8%, respectively. Little’s Missing Completely at Random test (MCAR; Little 2013) revealed that missing data were missing completely at random, χ2(5) = 2.17, p = 0.825. For children with and without missing data, there were no significant differences in terms of gender (χ2[1] = 2.60, p = 0.107), age (t[139.108] = 1.835, p = 0.068, d = 0.19), social dominance goals (t[134.01] = 1.31, p = 0.192, d = 0.16), bullying at Wave1 (t[1601] = 0.68, p = 0.496, d = 0.06). Missing data were handled using the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) method with the MLR estimation in Mplus. In order to promote the precision of FIML, parental education levels were included in the analyses as auxiliary variables. The FIML method can yield unbiased estimations of coefficients with auxiliary variables at present (Little 2013).

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

The descriptive statistics and correlations are presented in Table 1. At the individual level, boys scored higher than girls in bullying at Wave 1 (t[1601] = 11.46, p < 0.001, d = 0.57) and Wave 2 (t[1476] = 11.34, p < 0.001, d = 0.58). However, there was no gender difference in social dominance goals (t[1573] = 0.99, p = 0.322, d = 0.05). Bullying was highly stable between the two waves (r = 0.79, p < 0.001), and social dominance goals was positively correlated with bullying at Wave 1 (r = 0.28, p < 0.001) and Wave 2 (r = 0.27, p < 0.001). Among classroom-level variables, classroom status hierarchy was negatively associated with classroom size (r = −0.46, p = 0.002) and classroom proportion of boys (r = −0.36, p = 0.020).

Multilevel Models

The unconditional model

The ICC of Wave 2 bullying was 0.008, indicating that only 0.8% of the variance in Wave 2 bullying was due to differences between classrooms. Although the between-classroom variability was small, multi level models were used due to the hierarchical nature of the data (Julian 2001). Besides, the aim of the present study was not to explain the class-level variance of bullying, but the class-level variance of the social dominance goal–bullying association.

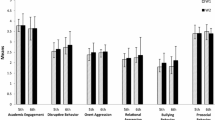

The individual-level model

First, a random intercept model was tested. In this model, the effects of individual-level predictors were fixed across classrooms. As shown in Table 2, after controlling for prior bullying behavior, being a boy (b = 0.027, SE = 0.041, p = 0.003) and having social dominance goals (b = 0.014, SE = 0.006, p = 0.013) were positively associated with increases in bullying. Furthermore, the results showed that gender moderated the longitudinal association between social dominance goals and bullying (b = 0.016, SE = 0.006, p = 0.005). As shown in Fig. 1, the association between social dominance goals and bullying behavior was stronger for boys than for girls (for boys: b = 0.021, SE = 0.008, p = 0.009; for girls: b = 0.005, SE = 0.003, p = 0.068). Turning to random effects model, the paths from social dominance goals to bullying were allowed to vary randomly across classrooms. The results revealed that the effect of social dominance goals on bullying varied significantly across classrooms (Var = 1.67 × 10−04, p = 0.033). Altogether the individual-level predictors explained 65.5% of the variability in bullying behavior at Wave 2.

The classroom-level model

As shown in Table 2, classroom size was negatively associated with bullying, indicating that bullying was more prevalent in classrooms with fewer students (b = −0.001, SE = 0.0002, p < 0.001). Grade (b = −0.008, SE = 0.004, p = 0.076) and classroom status hierarchy (b = 0.093, SE = 0.054, p = 0.083) were marginally significant predictors of bullying at Wave 2, suggesting that bullying may be more prevalent in middle childhood (i.e., lower grades) and in classrooms with a stronger status hierarchy. Moreover, consistent with our hypotheses, significant cross-level interactions indicated that the longitudinal association between social dominance goals and bullying was moderated by classroom proportion of boys (b = 0.210, SE = 0.081, p = 0.010) and classroom status hierarchy (b = 0.275, SE = 0.069, p < 0.001). To clarify the nature of the significant interactions of interest, post-hoc probing was conducted as recommended by Aiken and West (1991). Simple slope tests were employed to analyze the effect of social dominance goals on self-reported bullying by comparing simple slopes for low (−1 SD) and high (+1 SD) levels of proportion of boys and classroom status hierarchy. As shown in Fig. 2, social dominance goals had positive association with bullying in the classrooms with a high proportion of boys (b = 0.025, SE = 0.006, p < 0.001), rather than in those with a low proportion of boys (b = 0.003, SE = 0.008, p = 0.704). As shown in Fig. 3, children who endorsed social dominance goals were more likely to display increased levels of bullying in high-hierarchy classrooms (b = 0.026, SE = 0.008, p < 0.001) but not in low-hierarchy classrooms (b = 0.001, SE = 0.005, p = 0.790). Altogether, classroom-level predictors explained 72.0% of the variance in bullying between classrooms, and 64.3% of the variance in the social dominance goals–bullying slope.

Supplementary Analyses

As a supplementary analysis, whether the moderating effect of classroom status hierarchy varied across genders or grades was explored. Four interaction terms were added to the classroom-level model, including gender × classroom status hierarchy, grade × classroom status hierarchy, gender × social dominance goals × classroom status hierarchy, and grade × social dominance goals × classroom status hierarchy. The results revealed that the moderating role of classroom status hierarchy was consistent across grades (b = 0.070, SE = 0.190, p = 0.715) and genders (b = 0.137, SE = 0.235, p = 0.561).

In addition, to confirm the robustness of the present findings, sensitivity analyses were employed with ten randomly selected pooled samples, each of which contained 30 classes. The interaction between social dominance goals and gender was replicated in eight out of ten iterations; the interaction between social dominance goals and classroom gender distribution was replicated in seven out of ten iterations; and the interaction between social dominance goals and classroom status hierarchy was replicated in ten out of ten iterations.

Discussion

Bullying behavior is widely considered to be driven by the quest for high status and social dominance in the peer group (Pellegrini 2002; Salmivalli and Peets 2008). However, it remains unclear how contextual factors have an impact on the link between children and adolescents’ endorsement of social dominance goals and bullying behavior. In particular, classroom status hierarchy, which reflects the social status inequality in a classroom, may further motivate bullying behaviors among those with strong social dominance goals (Garandeau et al. 2011, 2014).To fill this gap, the present 1-year longitudinal multilevel study examined whether classroom status hierarchy moderates the prospective association between social dominance goals and bullying. Moreover, the moderating effects of other individual and classroom characteristics (e.g., gender, grade, classroom size, gender distribution) were also tested.

Previous cross-sectional studies reported a positive concurrent association between social dominance goals and bullying (Caravita and Cillessen 2012; Olthof et al. 2011; Sijtsema et al. 2009). In line with previous studies, the present study revealed that social dominance goals predicted increases in bullying over time after controlling the stability of bullying. The current finding indicated that, similar to their Western counterparts, Chinese children who were oriented toward social dominance engaged in bullying, although bullying is highly discouraged in Chinese culture. Thus, this finding echoed the evolutionary perspective of bullying, according to which, bullying can be viewed as a functional behavior that serves to achieve a dominant status in the group (Hawley 1999; Volk et al. 2012). Notably, the present study found high stability of bullying over 1 year (r = 0.79), suggesting that the role of bully is highly stable across time. This stability coefficient is in accordance with previous findings (Garandeau et al. 2014; Reijntjes et al. 2013). For example, Reijntjes et al. (2013) found that the stability coefficient of peer-reported bullying ranges 0.74–0.81 across 1 year. Our analyses revealed significant longitudinal effects of social dominance goals on bullying despite the high stability of bullying, which underscores the determining role of endorsing social dominance goals in the development of bullying behavior.

Next, this study tested the moderating role of classroom status hierarchy in the social dominance goals–bullying association. Given the emphasis on status hierarchy in Chinese classrooms (Schwartz et al. 2010), it is important to evaluate the function of classroom status hierarchy under Chinese culture. As expected, these results showed that children who endorsed social dominance goals were more likely to engage in bullying a year later in classrooms where power was less equally distributed. In contrast, there was no prospective association between social dominance goals and bullying in more egalitarian classrooms. A possible explanation could be generated from the goal-framing approach (Lindenberg 2013). Specifically, dominance-seeking children are sensitive to, and their goal is aroused by clear social benefits and low costs related to bullying (Veenstra et al. 2007). In classrooms with high social status hierarchy (i.e., hierarchical contexts), aggressive behavior is associated with higher popularity (Garandeau et al. 2011; Laninga-Wijnen et al. 2019) and victims are more easily dominated (Ahn et al. 2010). When spotting these social cues in classrooms with a clear status hierarchy, children are more likely to bully the weak to gain social dominance. In summary, the current findings extend the literature on how individual characteristics interact with contextual characteristics in predicting bullying by providing evidence that classroom status hierarchy influences the behavioral strategies of dominance-aspiring children.

These findings revealed how social status inequality in a classroom can harm students’ psychosocial adjustment, which echoes findings from research on the causal relations between economic inequality and population health (Pickett and Wilkinson 2015). National income inequality intensifies competition and feelings of insecurity and weakens interpersonal relationships within societies by decreasing trust among people (Pickett and Wilkinson 2015), thereby increasing the prevalence of social-emotional problems, including bullying behavior (Elgar et al. 2013; Melgar and Rossi 2012). The present findings corroborate those from this branch of literature by highlighting the psychological cost of inequality in human groups, regardless of the type (e.g., economic or social status) or the group size (e.g., a classroom or a nation).

Finally, this study tested the role of demographic variables in the association between social dominance goals and bullying. Consistent with previous research (Kiefer and Ryan 2008; Kiefer and Wang 2016; Ojanen et al. 2012), the results revealed that boys with higher social dominance goals tended to bully others more than girls with similar goals. This gender difference might be due to bullying being more normative (Smith et al. 2019) and more rewarded with social status among boys (Caravita and Cillessen 2012). As expected, such gender-specific norms could also be observed at the classroom level: the social dominance goals–bullying association was only evident in classrooms with a higher proportion of boys. The moderating effect of gender and gender distribution may reflect that, although the Participant Role Questionnaire does not distinguish between forms of bullying, most participants might recognize bullying as an overt behavior. As studies have shown higher popularity rewards for relationally aggressive girls than relationally aggressive boys (Cillessen and Mayeux 2004), social dominance goals may be more strongly related to relational bullying among girls. However, studies have failed to find gender differences in the association between social dominance goals and relational aggression (Kiefer and Wang 2016; Ojanen et al. 2012).

The results also revealed that the association between social dominance goals and bullying did not vary across grade level. This finding is consistent with previous studies (Caravita and Cillessen 2012), indicating that the quest of social dominance equally predicts bullying in middle childhood and early adolescence. With regard to classroom size, in line with previous studies (Garandeau et al. 2014, 2019), the results showed that classroom size was negatively related with bullying. However, classroom size did not moderate the social dominance goals–bullying association. The results might be related to the relatively large classroom size in the sample. Larger classrooms are typically made up of multiple peer groups, which could allow victims to escape the control of ringleader bullies and their followers, thereby lowering the status-rewards attached to bullying (Garandeau et al. 2019).

The present study has several strengths. First, whereas previous studies have examined the concurrent association between social dominance goals and bullying behavior, this study, guided by the goal-framing theory (Lindenberg 2013), focused on how classroom status hierarchy as well as other classroom context features moderate this association with a longitudinal design. Second, using a 1-year longitudinal design, the present study controlled for prior bullying and provides a rigorous test of the effects of individual-level and classroom-level factors on subsequent bullying. Finally, this study investigated an understudied, but very large, non-western culture and population, providing a new vision of group dynamics in vertical-collectivistic cultural contexts.

The findings of this study inform anti-bullying programs in two ways. To begin with, children who desire social dominance are more likely to engage in bullying. For these children, it may be useful to teach them alternative, prosocial ways to obtain status, power, and dominance. According to the meaningful roles approach (Ellis et al. 2016), teachers could assign these children to high-status jobs that require responsibility and altruism (e.g., technology assistant) and reinforce their behaviors through peer-to-peer praise notes. However, more evidence of the effectiveness of this approach is needed before its use can be recommended, as there is a risk that dominance-oriented children may use their newly gained high status (from the meaningful roles tasks) to engage in bullying. Moreover, randomized control trials are needed to evaluate this approach as a promising method to reduce children’s bullying behavior. Second, the results suggest that minimizing status discrepancies among children could diminish the likelihood that dominance-oriented children will resort to bullying others. That is, in order to build a safer classroom environment, teachers should intervene in existing hierarchical relationships between children and create more egalitarian classroom structures by mitigating status extremes and supporting isolated students (Garandeau et al. 2011, 2014; Gest and Rodkin 2011). More importantly, considering the characteristics of Chinese classrooms, teachers should not grant excessive power to specific students.

Despite these strengths, it is important to consider the methodological limitations of this study. First, although there was significant classroom-level variation in the association between social dominance goal and bullying, the classroom-level variation of bullying was relatively small, which limited the detection of classroom-level predictors’ main effects on bullying. Second, a maximum of three bullies were allowed to be nominated, which might underestimate students’ bulling behavior. However, there is evidence that utilizing limited and unlimited nominations of bullying lead to comparable results (Gommans and Cillessen 2015). Further research that replicate our findings using unlimited nominations is warranted. Finally, because bullying was operationalized as a unified construct, potential differences between overt and relational forms of bullying could not be explicitly tested. As relational bullying may be a more effective strategy in acquiring and maintaining social dominance in the peer group (Cillessen and Mayeux 2004; Ojanen and Findley-Van Nostrand 2014), considering the distinctions between relational and overt bullying would be an important direction for future research.

Future research may further expand on the current findings in two ways. First, it may focus on social goals other than social dominance goals and their association with bullying. For example, a lack of communal goals (i.e., striving for positive relationships with others, Caravita and Cillessen 2012) might be considered as one of the reasons for bullying (Caravita and Cillessen 2012). A recent study also revealed that communal goals mitigated the positive association between agentic goals and direct aggression (Sijtsema et al. 2020). Future studies would benefit from considering multiple goals simultaneously. Furthermore, research could take further steps in examining the process through which classroom status hierarchy moderates the link between social dominance goals and bullying. For example, as a possible cognitive mechanism, children who are oriented to social dominance may perceive bullying instead of other positive behaviors as an instrument to gain dominance in hierarchical classroom contexts (Li and Hu 2018).

Conclusion

Bullying behavior is motivated by the pursuit of social dominance in the peer group (Pellegrini 2002; Salmivalli and Peets 2008). Research has shown that social dominance goals are positively associated with bullying in middle childhood and early adolescence (Caravita and Cillessen 2012; Olthof et al. 2011; Sijtsema et al. 2009). Yet, it is important to note that this association may be influenced by the classroom context, as bullying may be related to different costs and benefits across classrooms. The current study examined the role classroom status hierarchy in the longitudinal association between social dominance goals and bullying in middle childhood and early adolescence. The findings indicated that youth striving for social dominance goals were more likely to engage in bullying behavior in more hierarchical classrooms. The current findings have implications for future antibullying practices. Specifically, to prevent dominance-oriented children from bullying others, teachers should make efforts to minimize status discrepancies and build egalitarian relationships among classmates.

References

Ahn, H. J., Garandeau, C. F., & Rodkin, P. C. (2010). Effects of classroom embeddedness and density on the social status of aggressive and victimized children. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 30(1), 76–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431609350922.

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Caravita, S. C., & Cillessen, A. H. N. (2012). Agentic or communal? Associations between interpersonal goals, popularity, and bullying in middle childhood and early adolescence. Social Development, 21(2), 376–395. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2011.00632.x.

Chen, G., Kong, Y., Deater-Deckard, K., & Zhang, W. (2018). Bullying victimization heightens cortisol response to psychosocial stress in Chinese children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 46(5), 1051–1059. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-017-0366-6.

Chen, L., Zhang, W., Ji, L., & Deater‐Deckard, K. (2019). Developmental trajectories of Chinese adolescents’ relational aggression: associations with changes in social‐psychological adjustment. Child Development, 90(6), 2153–2170. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13090.

Cillessen, A. H. N., & Marks, P. (2011). Conceptualizing and measuring popularity. In A. Cillessen, D. Schwartz & L. Mayeux (Eds), Popularity in the peer system (pp. 25–56). New York, NY: Guilford.

Cillessen, A. H. N., & Mayeux, L. (2004). From censure to reinforcement: developmental changes in the association between aggression and social status. Child Development, 75(1), 147–163. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00660.x.

Custers, R., & Aarts, H. (2010). The unconscious will: how the pursuit of goals operates outside of conscious awareness. Science, 329(5987), 47–50. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1188595.

de Bruyn, E. H., Cillessen, A. H. N., & Wissink, I. B. (2010). Associations of peer acceptance and perceived popularity with bullying and victimization in early adolescence. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 30(4), 543–566. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431609340517.

Elgar, F. J., Pickett, K. E., Pickett, W., Craig, W., Molcho, M., Hurrelmann, K., & Lenzi, M. (2013). School bullying, homicide and income inequality: a cross-national pooled time series analysis. International Journal of Public Health, 58(2), 237–245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-012-0380-y.

Ellis, B. J., Volk, A. A., Gonzalez, J. M., & Embry, D. D. (2016). The meaningful roles intervention: an evolutionary approach to reducing bullying and increasing prosocial behavior. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 26(4), 622–637. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12243.

Garandeau, C. F., Ahn, H. J., & Rodkin, P. C. (2011). The social status of aggressive students across contexts: the role of classroom status hierarchy, academic achievement, and grade. Developmental Psychology, 47(6), 1699–1710. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025271.

Garandeau, C. F., Lee, I. A., & Salmivalli, C. (2014). Inequality matters: classroom status hierarchy and adolescents’ bullying. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(7), 1123–1133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-013-0040-4.

Garandeau, C. F., Yanagida, T., Vermande, M. M., Strohmeier, D., & Salmivalli, C. (2019). Classroom size and the prevalence of bullying and victimization: testing three explanations for the negative association. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2125 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02125.

Gest, S. D., & Rodkin, P. C. (2011). Teaching practices and elementary classroom peer ecologies. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 32(5), 288–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2011.02.004.

Gommans, R., & Cillessen, A. H. N. (2015). Nominating under constraints: a systematic comparison of unlimited and limited peer nomination methodologies in elementary school. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 39, 77–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025414551761.

Halevy, N., Chou, E. Y., & Galinsky, A. D. (2011). A functional model of hierarchy. Organizational Psychology Review, 1(1), 32–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/2041386610380991.

Hawley, P. H. (1999). The ontogenesis of social dominance: a strategy-based evolutionary perspective. Developmental Review, 19(1), 97–132. https://doi.org/10.1006/drev.1998.0470.

Huitsing, G., Snijders, T. A., Van Duijn, M. A., & Veenstra, R. (2014). Victims, bullies, and their defenders: a longitudinal study of the coevolution of positive and negative networks. Development and Psychopathology, 26(3), 645–659. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579414000297.

Jarvinen, D. W., & Nicholls, J. G. (1996). Adolescents’ social goals, beliefs about the causes of social success, and satisfaction in peer relations. Developmental Psychology, 32(3), 435–441. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.32.3.435.

Ji, L., Zhang, W., & Jones, K. (2016). Chinese children’s experience of and attitudes towards bullying and victimization: A cross-cultural comparison between China and England. In P. Smith, K. Kwak & Y. Toda. (Eds), School bullying in different cultures: Eastern and western perspectives (pp. 170–188). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Julian, M. W. (2001). The consequences of ignoring multilevel data structures in nonhierarchical covariance modeling. Structural Equation Modeling, 8(3), 325–352. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0803_1.

Kiefer, S. M., & Wang, J. H. (2016). Associations of coolness and social goals with aggression and engagement during adolescence. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 44, 52–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2016.02.007.

Kiefer, S., & Ryan, A. (2008). Striving for social dominance over peers: the implications for academic adjustment during early adolescence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(2), 417–428. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.100.2.417.

Kuppens, S., Grietens, H., Onghena, P., Michiels, D., & Subramanian, S. V. (2008). Individual and classroom variables associated with relational aggression in elementary-school aged children: a multilevel analysis. Journal of School Psychology, 46(6), 639–660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2008.06.005.

LaFontana, K. M., & Cillessen, A. H. (2010). Developmental changes in the priority of perceived status in childhood and adolescence. Social Development, 19(1), 130–147. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00522.x.

Laninga-Wijnen, L., Harakeh, Z., Dijkstra, J. K., Veenstra, R., & Vollebergh, W. (2020). Who sets the aggressive popularity norm in classrooms? It’s the number and strength of aggressive, prosocial, and bi-Strategic adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 48(1), 13–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-019-00571-0.

Laninga-Wijnen, L., Harakeh, Z., Garandeau, C. F., Dijkstra, J. K., Veenstra, R., & Vollebergh, W. A. (2019). Classroom popularity hierarchy predicts prosocial and aggressive popularity norms across the school year. Child Development, 90(5), 637–653. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13228.

Li, Y., & Hu, Y. (2018). How to attain a popularity goal? Examining the mediation effects of popularity determinants and behaviors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(9), 1842–1852. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0882-x.

Li, Y., Xie, H., & Shi, J. (2012). Chinese and American children’s perceptions of popularity determinants: cultural differences and behavioral correlates. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 36(6), 420–429. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025412446393.

Lindenberg, S. (2013). Social rationality, self-regulation, and well-being: The regulatory significance of needs, goals, and the self. In R. Wittek, T. A. B. Snijders & V. Nee (Eds), Handbook of rational choice social research (pp. 72–112). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Little, T. D. (2013). Longitudinal structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press.

Melgar, N., & Rossi, M. (2012). A cross‐country analysis of the risk factors for depression at the micro and macro levels. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 71(2), 354–376. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1536-7150.2012.00831.x.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2012). Mplus statistical modeling software. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.

Niu, L., Jin, S., Li, L., & French, D. C. (2016). Popularity and social preference in Chinese adolescents: associations with social and behavioral adjustment. Social Development, 25(4), 828–845. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12172.

Ojanen, T., Findley, D., & Fuller, S. (2012). Physical and relational aggression in early adolescence: associations with narcissism, temperament, and social goals. Aggressive Behavior, 38(2), 99–107. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21413.

Ojanen, T., & Findley-Van Nostrand, D. (2014). Social goals, aggression, peer preference, and popularity: longitudinal links during middle school. Developmental Psychology, 50, 2134–2143. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037137.

Olthof, T., Goossens, F. A., Vermande, M. M., Aleva, E. A., & van der Meulen, M. (2011). Bullying as strategic behavior: relations with desired and acquired dominance in the peer group. Journal of School Psychology, 49(3), 339–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2011.03.003.

Olweus, D. (2013). School bullying: development and some important challenges. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9, 751–780. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185516.

Pellegrini, A. D. (2002). Bullying, victimization, and sexual harassment during the transition to middle school. Educational Psychologist, 37(3), 151–163. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3703_2.

Pellegrini, A. D., & Long, J. D. (2002). A longitudinal study of bullying, dominance, and victimization during the transition from primary school through secondary school. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 20(2), 259–280. https://doi.org/10.1348/026151002166442.

Pickett, K. E., & Wilkinson, R. G. (2015). Income inequality and health: a causal review. Social Science & Medicine, 128, 316–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.12.031.

Pouwels, J. L., van Noorden, T. H., & Caravita, S. C. (2019). Defending victims of bullying in the classroom: the role of moral responsibility and social costs. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 84, 103831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2019.103831.

Reijntjes, A., Vermande, M., Olthof, T., Goossens, F. A., Van De Schoot, R., Aleva, L., & Van Der Meulen, M. (2013). Costs and benefits of bullying in the context of the peer group: a three wave longitudinal analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41(8), 1217–1229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-013-9759-3.

Rose, A. J., & Rudolph, K. D. (2006). A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychological Bulletin, 132(1), 98–131. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98.

Salmivalli, C., & Peets, K. (2008). Bullies, victims, and bully–victim relationships. In K. Rubin, W. Bukowski & B. Laursen (Eds), Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups (pp. 322–340). New York: Guilford Press.

Salmivalli, C., & Voeten, M. (2004). Connections between attitudes, group norms, and behaviour in bullying situations. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 28(3), 246–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250344000488.

Schwartz, D., Tom, S. R., Chang, L., Xu, Y., Duong, M. T., & Kelly, B. M. (2010). Popularity and acceptance as distinct dimensions of social standing for Chinese children in Hong Kong. Social Development, 19(4), 681–697. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2009.00558.x.

Sijtsema, J. J., Lindenberg, S. M., Ojanen, T. J., & Salmivalli, C. (2020). Direct aggression and the balance between status and affection goals in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01166-0.

Sijtsema, J. J., Veenstra, R., Lindenberg, S., & Salmivalli, C. (2009). Empirical test of bullies’ status goals: assessing direct goals, aggression, and prestige. Aggressive Behavior, 35(1), 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20282.

Smith, P. K., López-Castro, L., Robinson, S., & Görzig, A. (2019). Consistency of gender differences in bullying in cross-cultural surveys. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 45, 33–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.04.006.

te Grotenhuis, M., Pelzer, B., Eisinga, R., Nieuwenhuis, R., Schmidt-Catran, A., & Konig, R. (2017). When size matters: advantages of weighted effect coding in observational studies. International Journal of Public Health, 62, 163–167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-016-0901-1.

Triandis, H. C. (1995). Individualism & collectivism. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Tseng, W. L., Banny, A. M., Kawabata, Y., Crick, N. R., & Gau, S. S. F. (2013). A cross‐lagged structural equation model of relational aggression, physical aggression, and peer status in a Chinese culture. Aggressive Behavior, 39(4), 301–315. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21480.

Veenstra, R., Lindenberg, S., Zijlstra, B. J., De Winter, A. F., Verhulst, F. C., & Ormel, J. (2007). The dyadic nature of bullying and victimization: testing a dual‐perspective theory. Child Development, 78(6), 1843–1854. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01102.x.

Volk, A. A., Camilleri, J. A., Dane, A. V., & Marini, Z. A. (2012). Is adolescent bullying an evolutionary adaptation? Aggressive Behavior, 38(3), 222–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-018-0005-y.

Wright, M. F., Li, Y., & Shi, J. (2014). Chinese adolescents’ social status goals: associations with behaviors and attributions for relational aggression. Youth & Society, 46(4), 566–588. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X12448800.

Zhang, W., Chen, L., & Chen, G. (2016). Research on bullying in mainland China. In P. Smith, K. Kwak & Y. Toda. (Eds), School bullying in different cultures: Eastern and western perspectives (pp. 113–132). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zwaan, M., Dijkstra, J. K., & Veenstra, R. (2013). Status hierarchy, attractiveness hierarchy and sex ratio: three contextual factors explaining the status–aggression link among adolescents. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 37(3), 211–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025412471018.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to sincerely thank all participating students for their contributions, as well as research assistants who have helped in designing the study and collecting the data.

Funding

This study was supported by the Major Projects of Philosophy and Social Sciences Research, Ministry of Education (17JZD058), Science and Technology Plan for Young Scholars supported by Education Department of Shandong (2019RWF012), and the Academy of Finland Flagship Programme (320162).

Data Sharing and DeclarationThis manuscript’s data will not be deposited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.P. conceived of the study and participated in the interpretation of the data, performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript; L.Z. helped in performing the statistical analysis and the interpretation of the data, and drafted the manuscript; L.J. participated in the research design; C.F.G. and C.S. helped in drafting the manuscript and participated in the interpretation of the data; W.Z. conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pan, B., Zhang, L., Ji, L. et al. Classroom Status Hierarchy Moderates the Association between Social Dominance Goals and Bullying Behavior in Middle Childhood and Early Adolescence. J Youth Adolescence 49, 2285–2297 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01285-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01285-z