Abstract

Moral disengagement is a social cognitive process that has been extensively applied to transgressive behaviors, including delinquency, aggression and illicit substance use. However, there has been limited research on moral disengagement as it relates to underage drinking. The current study aimed to examine moral disengagement contextualized to underage drinking and its longitudinal relationship to alcohol use. Moreover, the social context in which adolescent alcohol use typically occurs was also considered, with a specific emphasis on the social sanctions, or social outcomes, that adolescents anticipate receiving from friends for their alcohol use. Adolescents were assessed across three time-points, 8 months apart. The longitudinal sample consisted of 382 (46 % female) underage drinkers (12–16 years at T1). Parallel latent growth curve analysis was used to examine the bi-directional influence of initial moral disengagement, anticipated social outcomes, and alcohol use on subsequent growth in moral disengagement, anticipated social outcomes and alcohol use. The interrelation of initial scores and growth curves was also assessed. The findings revealed that, in the binary parallel analyses, initial moral disengagement and anticipated social outcomes both significantly predicted changes in alcohol use across time. Moreover, initial anticipated social outcomes predicted changes in moral disengagement. These findings were not consistently found when all three process analyses were included in a single model. The results emphasize the impact of social context on moral disengagement and suggest that by targeting adolescents’ propensity to justify or excuse their drinking, as well as the social outcomes adolescents anticipate for being drunk, it may be possible to reduce their underage drinking.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Alcohol is the most widely used substance by adolescents in Western countries (Henderson et al. 2013; Hibell et al. 2012; Johnston et al. 2015; White and Bariola 2012). By mid-adolescence, many young people have started consuming alcohol and it is during this developmental period that adolescents’ alcohol use escalates (Gutman et al. 2011; Henderson et al. 2013). There are many adverse consequences associated with adolescent alcohol use including growing evidence that the neurotoxic effects of alcohol may adversely affect the maturing adolescent brain (Bava and Tapert 2010; Clark et al. 2008; Crews et al. 2007) and that heavy alcohol use by adolescents may result in long-term alcohol abuse and dependence (Guttmannova et al. 2011; Pitkänen et al. 2008). Given these negative consequences and the legal restrictions and public health warnings aimed at reducing adolescent drinking (Donaldson 2010; British Columbia Ministry of Health Services 2010, National Health and Medical Research Centre 2009; World Health Organization 2007), underage drinking is commonly considered a problem behavior and it is also frequently associated with other transgressive behaviors including aggression, violence, lying, stealing and illicit substance use (Arbeit et al. 2014; Eaton et al. 2012; McAtamney and Morgan 2009; Scholes-Balog et al. 2013). Although moral processes, including moral disengagement, neutralization techniques, self-serving cognitive distortions and moral neutralization have been advanced to explain how adolescents self-regulate delinquent and aggressive behaviors (Bandura 1986; Barriga and Gibbs 1996; Ribeaud and Eisner 2010; Sykes and Matza 1957), there has been limited application of these processes to underage drinking (Newton et al. 2014; Piacentini et al. 2012; Quinn and Bussey 2015a). A primary aim of this study, therefore, was to focus on how moral processes, specifically moral disengagement, longitudinally relate to adolescent alcohol use. A secondary aim was to examine the broader social context in which moral disengagement occurs. This broader context is examined from the perspective of social cognitive theory, a comprehensive theory of moral agency that considers developmental processes, that are both personal and social, and has been applied in a variety of domains (Bandura 1986).

From the social cognitive theory perspective, moral disengagement is conceptualized as a social cognitive process whereby transgressive behavior is justified or excused to enable its performance free of self-censure (Bandura 1986). The conceptualization of moral disengagement is similar to Sykes and Matza’s (1957) neutralization theory. Both theoretical positions propose that endorsing a moral value or standard does not necessarily lead to moral non-transgressive behavior. Self-sanctions including guilt and self-blame normally keep behavior in line with moral standards. These self-sanctions can be reduced or deactivated, however, through disengagement strategies or neutralization techniques, enabling transgressive behavior to be performed free of self-censure (Bandura 1986; Sykes and Matza 1957). Both theoretical perspectives propose different mechanisms by which behavior is disengaged or neutralized. From Bandura’s social cognitive theory (1986, 2002), eight mechanisms are proposed (moral justification, euphemistic labelling, advantageous comparison, displacement of responsibility, diffusion of responsibility, distorting or minimising the consequences, attribution of blame, dehumanization), whereas Sykes and Matza’s (1957) proposed five techniques of neutralization (appeal to a higher authority, denial of responsibility, denial of harm/injury, denial of the victim, condemnation of the condemners). Particularly for moral disengagement, although different mechanism are proposed to explain how transgressive behavior may be justified or excused, all disengagement mechanisms are highly interrelated, and have consistently been shown to measure the same underlying construct of moral disengagement (Bandura et al. 1996; Caprara et al. 2009; Lucidi et al. 2008; Paciello et al. 2008; Quinn and Bussey 2015a).

Moral disengagement and neutralization techniques have both been shown to distinguish between juvenile offenders and non-offenders (Shields and Whitehall 1994; Shulman et al. 2011). Neutralization techniques have also been applied to other criminal activities including, stealing (Chi-mei 2008; Jacobs and Copes 2015), drink driving (Kobin 2013) and illicit substance use (Jarvinen and Demant 2011), while moral disengagement has been more broadly applied to bullying, aggression, violence (Bandura et al. 1996; Caprara et al. 2014; Gini et al. 2014), antisocial sporting behavior (Stanger et al. 2013), steroid use in sport (Lucidi et al. 2008), civic engagement (Caprara et al. 2009; Hardy et al. 2015) and unethical decision making (Detert et al. 2008). High endorsements of moral disengagement and neutralization techniques have consistently been associated with engagement in transgressive behavior.

For alcohol use, neutralization techniques have been investigated in samples of college students (Dodder and Hughes 1993; Hughes and Dodder 1983). However, although there was a strong association between neutralization techniques and college drinking, ninety percent of college students did not believe drinking was wrong, and, therefore, neutralization theory could not be applied to college drinking (Dodder and Hughes 1993). For drinking in particular, it is important to distinguish between drinking alcohol and drinking alcohol underage. While drinking alcohol is widely accepted among the adult population, most countries legally restrict its supply to minors (WHO 2007). Drinking alcohol during adolescents is less normative than college drinking (White and Hingson 2013). Moreover, drinking is not predominately approved by adolescents, with approval for drinking, and levels of drinking, actually declining in the past decade (Henderson et al. 2013; Johnston et al. 2015; White and Bariola 2012). Although it may be inappropriate to apply neutralization and moral disengagement concepts to college drinking, these concepts can be applied to adolescent drinking. Recent research (Quinn and Bussey 2015a) has shown that consistent with Bandura’s (1986) social cognitive theory adolescents do hold standards against underage drinking and moral disengagement does moderate the relationship between these standards and adolescents’ experience of negative self-sanctions.

The more adolescents justify or excuse delinquent behavior, the more they engage in drinking underage and risky drinking (Newton et al. 2012, 2014). This relationship has been found cross-sectionally across time (Newton et al. 2014). However, how changes in moral disengagement relate to changes in alcohol use has not yet been investigated. Additionally, it has recently been shown that moral disengagement, contextualized to underage drinking, relates more strongly to adolescents’ alcohol use than to a general measure of moral disengagement measuring justifications and excuses for a broad range of transgressive behaviors (Quinn and Bussey 2015a). To more fully understand how moral disengagement longitudinally relates to adolescent alcohol use, this study examines moral disengagement in the context of underage drinking.

Previous studies examining how moral disengagement changes over time have predominately focused on delinquency or aggression (Caravita et al. 2014; Paciello et al. 2008; Shulman et al. 2011). Moral disengagement, contextualized to delinquency, has been shown to increase during early adolescence, and this increase has been associated with an increase in school aggression (Caravita et al. 2014). During mid to late adolescence, moral disengagement has been shown to generally decline and this decline has been associated with a decline in aggression and delinquent conduct (Paciello et al. 2008; Shulman et al. 2011). It is important to determine whether these findings can be extended to other contexts, in particular underage drinking. Moreover, while delinquency generally decreases with age during mid-adolescence (Connolly et al. 2015; Abar et al. 2014), underage drinking commonly increases (Choukas-Bradley et al. 2015; Colder et al. 2014; Duncan et al. 1995), therefore, rather than decreasing, it is possible that moral disengagement for underage drinking will actually increase across time. Therefore, this study will investigate how moral disengagement changes over time in the context of underage drinking and also whether changes in moral disengagement relate to changes in underage drinking.

According to social cognitive theory (Bandura 1986), behavior is not only motivated by self-sanctions but also by social influences. However, there has been limited investigation of the impact of social influences on moral disengagement. For adolescents, parents and peers have been identified as key socializing influences (Collins et al. 2000) who have a significant impact on adolescents’ alcohol use (Bahr et al. 2005; Ryan et al. 2010). During mid-adolescence, the impact of peers on adolescent drinking is particularly acute (Aas and Klepp 1992; Allen et al. 2003; Ford and Hill 2012; Mrug and McCay 2013). Adolescents have been shown to consume more alcohol in larger peer groups (Anderson and Brown 2011) and greater tolerance of substance use among school peers has been related to greater alcohol and substance use by adolescents (Kumar et al. 2002). Moreover, adolescents who associate with deviant peers (Allen et al. 2012; Light et al. 2013; Trucco et al. 2011) or who perceive more of their friends and peers to be drinkers (Anderson and Brown 2011; Danielsson et al. 2010; Deutsch et al. 2014; Musher-Eizenman et al. 2003; Reboussin et al. 2006; Simons-Morton 2004) consume more alcohol themselves.

The limited research that has examined the impact of social influences on moral disengagement was conducted in a bullying context (Caravita et al. 2014; Sijtsema et al. 2014). It was shown that adolescents who were exposed to peers who held pro-bullying attitudes or peers who morally justify bullying were more likely to morally disengage and to bully (Caravita et al. 2014; Sijtsema et al. 2014). Although it has been suggested that the social sanctions anticipated from peers may impact upon the degree to which individuals justify or excuse their behavior, this has not yet been investigated (Caravita et al. 2014). Another aim of this study was to address this gap by investigating the interrelationship between moral disengagement and social sanctions anticipated from peers and how both these factors relate to adolescent alcohol use.

Bandura (1986) proposes that the anticipation of social praise and approval act as an incentive to perform behavior, while the anticipation of social disapproval and censure serve as a behavior deterrent. This process has some similarities to the conceptualization of injunctive norms in social norm theory (Perkins 2003) and subjective norms in the theory of reasoned action and the theory of planned behavior (Fishbein and Ajzen 1975; Ajzen 2005). Injunctive norms and subjective norms both refer to the perceived social acceptability for a behavior or its normative nature. These theoretical perspectives have been extensively applied to adolescent alcohol use, with considerable evidence that adolescents consume more alcohol if they anticipate approval, respect or acceptance from their peers for drinking than if they anticipate disapproval (Ford and Hill 2012; Kristjansson et al. 2010; Mrug and McCay 2013; Quinn and Bussey 2015b; Shamblen et al. 2014; Simons-Morton 2004; Smith and Rosenthal 1995; Tucker et al. 2008). Despite the consistently strong influence of peer sanctions on adolescent drinking, much of this research is based on cross-sectional studies. In one of the few longitudinal studies that has been conducted, it was shown that friendship groups exerted a stronger influence than the broader peer group, and that perceived approval during mid-adolescence did predict heavy drinking during late adolescence (Voogt et al. 2013). However, to our knowledge, no other studies have examined how the social outcomes anticipated from friends change over time or how these changes relate to adolescents alcohol use and to other internal motivators for drinking, such as moral disengagement. According to Bandura’s social cognitive theory (1986), anticipatory social outcomes can complement or contradict moral disengagement influences. When considering moral disengagement as an internal motivator for behavior, it is necessary to consider, from a longitudinal perspective, how the social sanctions adolescents anticipate receiving from their friends influences their propensity to morally disengage and to consume alcohol.

The understanding of this longitudinal relationship is particularly important considering that there are two prominent explanations for apparent peer or friendship influences: selection and socialization (Kandel 1978). Adolescents may be influenced by their friends because they are socialized into the values, attitudes and behaviors of their friendship network. Alternatively, adolescents may also select friends who hold or engage in similar values, attitudes or behaviors to themselves. Cross-sectionally, these two influences cannot be differentiated. Bandura (1986), in his social cognitive theory, proposed a bi-directional relationship whereby adolescents are both an influence on and are influenced by their friendship network. It is only through longitudinal research that these joint influences can be investigated.

The Current Study

The current study extends the extant literature on the relationship between moral disengagement and underage drinking, examining the interrelationship between moral disengagement, anticipated social outcomes from friends, and underage drinking across-time. To achieve this, the growth trends in alcohol use, moral disengagement and anticipated social outcomes are investigated first. In addition, as age and gender have consistently been associated with alcohol use, moral disengagement and anticipated social outcomes (Barchia and Bussey 2011; Mrug and McCay 2013; Quinn and Bussey 2015b; White and Bariola 2012), the relationship of age and gender to alcohol use, moral disengagement and anticipated social outcomes are investigated and subsequently included as control variables in the remaining analyses. We then examine the interrelationship between moral disengagement, anticipated social outcomes and alcohol use using parallel process latent growth models.

Consistent with prior latent growth modeling and epidemiological research (Australian Institute of Health & Welfare 2011; Choukas-Bradley et al. 2015; Colder et al. 2014; White and Bariola 2012), it was hypothesized that alcohol use would increase over time. Moral disengagement contextualized to delinquency has consistently been shown to decrease across mid-adolescence (Paciello et al. 2008; Shulman et al. 2011) and this corresponds to a decrease in delinquency over this time period. It was, therefore, hypothesized that corresponding to the increase in underage drinking, moral disengagement in underage drinking may also similarly increase. Cohort analyses have shown that anticipated disapproval from peers decreases through adolescence (Mrug and McCay 2013). Consistent with this previous research, it was expected that positive anticipated social outcomes from friends would increase across time.

Adolescent males have consistently been found to consume more alcohol (Australian Institute of Health & Welfare 2011; Reboussin et al. 2006) and to increase the intensity of their alcohol use at a faster rate (Mares et al. 2012; Jackson 2013) than do adolescent females. Adolescent males have also been shown to anticipate more peer approval for drinking (Mrug and McCay 2013; Quinn and Bussey 2015b) and to justify underage drinking more (Quinn and Bussey 2015a) than do adolescent females. It was hypothesized, therefore, that adolescent males, more than females, would report higher levels of alcohol use, moral disengagement, and anticipated social outcomes from friends, at the initial time point, and a greater increase in these variables over time.

As alcohol involvement and positive approval from peers for drinking increases with age (AHIW 2011; Hibell et al. 2012; White and Bariola 2012; Mrug and McCay 2013), it was anticipated that at the initial time point the older students would report higher levels of alcohol use and anticipated social outcomes than younger students. There is evidence that younger students experience a steeper increase in problem behavior over time (Duncan et al. 2000). It was, therefore, expected that the rate of change over time in alcohol use, moral disengagement, and anticipated social outcomes would be greater for younger than for older students.

In sum, the central aim of the study was to examine how moral disengagement and underage drinking interrelate across time. Based on previous cross-sectional findings (Newton et al. 2012, 2014; Quinn and Bussey 2015a), it was expected that initial levels of moral disengagement and underage drinking would be positively associated. Moral disengagement has consistently been shown to longitudinally predict bullying, aggression and delinquent behavior; however, there is inconsistent evidence as to whether bullying, aggressive and delinquent behavior predict subsequent moral disengagement (Barchia and Bussey 2011; Caprara et al. 2014; Paciello et al. 2008; Sticca and Perren 2015). It was hypothesized that, while growth in moral disengagement and underage drinking would be correlated across time, only initial levels of moral disengagement would predict the development of underage drinking across time.

When examining the relationship between social outcomes anticipated from friends and moral disengagement, although not previously examined, it was expected that initial levels of moral disengagement and positive anticipated social outcomes would be positively related. Consistent with social cognitive theory principles, it was further hypothesized that initial moral disengagement would predict the development of anticipated social outcomes, and that initial anticipated social outcomes would be associated with the development of moral disengagement. Similarly, it was expected that anticipated social outcomes would be related to alcohol use at the initial time point, that initial anticipated social outcomes would be associated with the increase in alcohol use over time, and that initial alcohol use would be related to the development of anticipated social outcomes.

Method

Participants and Sampling

Participants were 688 (52 % female) students from 10 metropolitan and regional non-governmental schools in New South Wales, Australia, obtained through convenience sampling. At the initial time point (T1), students were in grades 8 (n = 314, Mage = 13.51 years, age range 12–14 years) and 10 (n = 374, Mage = 15.43, age range 14–16 years). The mean age for the total sample at T1 was 14.58 years. Of the participants, 81 % were White, 8 % were Asian, 6 % Middle Eastern and 5 % were other. Data were collected across three time points with 8 months between each time point. Adolescents were included in the final longitudinal sample if, by the final survey point, they indicated that they had consumed a full standard drink of alcohol at least once in their lifetime (56 % of participants).

The final sample consisted of 382 (46 % female) students who at T1 were in grades 8 (n = 111, Mage = 13.54 years, age range 12–14 years) and 10 (n = 271, Mage = 15.48, age range 14–17 years) and had a mean age of 14.93 years. Of the participants 85 % were White, 7 % were Asian, 4 % Middle Eastern and 4 % were from other ethnic groups. Of those included in the final sample, at T1, the majority of adolescents had already consumed a full standard drink of alcohol (67 %, n = 240) or had a sip or taste of alcohol (26 %, n = 91). Only 7 % of students (n = 25) in the final sample had not consumed any alcohol at T1. Based on the responses to the question: “About how old were you when you had your first full standard drink of alcohol?” the mean drinking onset was 14 years old (SD = 1.49 years). Comparisons on demographic information between adolescents who had consumed a full standard drink in their lifetime by the final survey point and those who had not, indicated that adolescents who had consumed a full standard drink were more likely to be male (χ2 = 13.57, p < .001; 54 % compared to 40 %), to be White (χ2 = 7.99, p = .046; 85 % compared to 77 %) and to be in Grade 10 at T1 (χ2 = 95.78, p < .001; 71 % compared to 33 %).

Procedure

Data were collected every 8 months with T1 data collection commencing in the Winter of 2011. Informed written consent was obtained from parents at the beginning of the study and students provided written assent at each time point. For each wave, survey administration occurred in classrooms or halls in groups of approximately 20–100 adolescents. Standardized instructions were delivered by trained research assistants who then remained present during testing to answer individual student questions. Participants were assured verbally and in writing of the anonymity of their responses. To ensure confidentiality, adolescents were asked not to discuss their answers with peers. Additionally, although teachers were present to supervise the survey administration, they were asked to remain seated at their desk and not to circulate the room or look at student responses. The survey took approximately 45 min to complete. A unique identification code adapted from the SHAHRP study (McBride et al. 2006) was incorporated to link data across time without identifying an individual. The code included four information components: the first letter of the student’s mother’s first name, student’s day of birth, last two letters of student’s first name and last two letters of students’ last name. All participants entered a draw to win one of forty cinema tickets.

Measures

Alcohol Use

Alcohol frequency, quantity and frequency of heavy drinking were assessed using items taken from the SHAHRP ‘Patterns of Alcohol Use’ measure (McBride et al. 2006). Respondents reported for the past 3 months how often they had consumed an alcoholic drink (0 = never to 7 = everyday), how many alcoholic drinks they usually had on a day that they drank (0 = haven’t drunk to 7 = 13 or more drinks) and how often in the past 3 months they had consumed more than 4 standard drinks in a day (0 = never to 7 = everyday). Each item was standardized using the grand mean and composite standard deviation across the three measurement time points. The frequency, quantity and heavy drink items were then summed to create a composite alcohol use score for each time point (Vaughan et al. 2009). Internal reliability for the three-item composites was high (T1 = .86; T2 = .87; T3 = .87)

Moral Disengagement

The Underage Drinking Disengagement Scale (UDDS; Quinn and Bussey 2015a) was used to assess moral disengagement contextualized to underage drinking. The UDDS is an 18-item scale measuring six moral disengagement mechanisms with three items per mechanism. Items included “drinking alcohol is okay because it’s not as bad as using illegal drugs” and “if everyone at a party is drinking it is unfair to blame one kid for drinking”. Students rated each item on a 5-point scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Items for the scale were developed based on previous moral disengagement measures (Bandura et al. 1996; Lucidi et al. 2008; Paciello et al. 2008) and pilot interviews with 10 high school students. Potential items were rated by 18 experts (i.e. alcohol or moral disengagement researchers and high school teachers; Quinn and Bussey 2015a) for applicability to the six moral disengagement mechanisms, to underage drinking and to an adolescent sample. It has been demonstrated, through exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses on two separate samples of over 600 mid-adolescent students, that consistent with other moral disengagement scales (Bandura et al. 1996; Paciello et al. 2008) the 18-item UDDS has a single factor structure (Quinn and Bussey 2015a). Moreover, the UDDS has been shown to have a strong correlation with other measures of moral disengagement (r = .70) and still to relate to engagement in underage drinking and heavy episodic drinking over and above moral disengagement measures contextualized more broadly to delinquent behavior (Quinn and Bussey 2015a). Comparable with other measures of moral disengagement, the UDDS had good internal consistency (T1: α = .93; T2: α = .93; T3: α = .95). Higher UDDS scores indicate greater disengagement to underage drinking.

Anticipated Social Outcomes (ASO): Friends

The Drunk ASO friend sub-scale (Quinn and Bussey 2015b) was used to assess the social outcomes adolescents anticipate receiving from their friends for drinking alcohol. This scale consists of three items measuring the social outcomes adolescents anticipate receiving from their friends for having drunk alcohol to the point of drunkenness. Students were presented three times with the stem “You are drinking alcohol and it is obvious you are drunk. Your friends would…”. Each time the stem was presented students answered a different 4-point response scale (i.e., 1 = be totally disappointed with you for being drunk and 4 = be totally pleased with you for being drunk; 1 = think it is totally not ok that you are drunk and 4 = think it is totally ok that you are drunk; 1 = totally care that you are drunk alcohol and 4 = totally not care that you are drunk). This scale had good internal consistency (T1 = .87; T2 = .88; T3 = 90).

Data Analytic Strategy

A series of latent curve analyses were conducted in AMOS 21 (Arbuckle 2012) to examine the change in alcohol use, moral disengagement and anticipated social outcomes over time. Latent curve analysis was utilized because it is a flexible tool which considers intra-individual changes in behavior over time, while also considering the inter-individual differences in these changes (McArdle 1988; Meredith and Tisak 1990). The latent curve analysis, also referred to as latent growth modeling or LGM, was conducted in four stages (Duncan and Duncan 2004; Li et al. 2000).

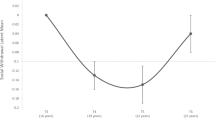

The first stage examined group and individual differences in alcohol use, moral disengagement and anticipated social outcomes over time using three unconditional growth models. For alcohol use, the linear growth model was estimated for T1, T2, and T3 alcohol use scores (Fig. 1). Linear growth was reflected by fixing the paths from the latent linear factor to alcohol use variables as 0, 1, 2. Alcohol use at time 1 had the initial value (0), since it was assumed that the growth process would continually develop from this first time point. A latent intercept variable was included in the model to examine the average alcohol use of each participant over the three time points. To achieve this, the paths from the latent intercept variable to the alcohol use variables were of equal weight (1). The mean intercept and linear factors were examined to determine the average initial alcohol use and the average rate of change in alcohol use over time. The variance of the intercept and linear factor were examined to assess individual differences in initial alcohol use and the rate of change in alcohol use over time. The linear growth model for moral disengagement and anticipated social outcomes was the same as that described above for alcohol use.

The second stage of analysis examined conditional growth models that included age and gender as time invariant predictors of the intercept and slope of alcohol use, moral disengagement and anticipated social outcomes. Next, three parallel process latent growth curves were used to examine how the trajectories of alcohol use and moral disengagement, alcohol use and anticipated social outcomes, and moral disengagement and anticipated social outcomes interrelated. Based on aprior hypotheses, it was anticipated that the intercepts and slopes of each of the growth models would correlate with each other. The intercept of one growth model was also expected to predict the linear slope of the second growth model, therefore cross-lagged predictions were added from the intercept to the slope for each of the models. Age and gender were included as time invariant covariates in each of the parallel latent growth models (see Fig. 2). Finally, a parallel latent growth model, with three latent growth curves was used to examine the interrelationship between all three trajectories of alcohol use, moral disengagement and anticipated social outcomes. The χ2 statistic, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) were used to assess model fit (Hu and Bentler 1999; Vandenberg and Lance 2000). The Browne–Cudeck Criterion (BCC) and Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) were used to compare alternate models to each other. When comparing two models smaller values of the AIC and BCC were considered to denote better fit of the hypothesized model (Browne and Cudeck 1993; Hu and Bentler 1999).

Missing Data

At T1, 357 of students from the final sample completed the questionnaire (93 % of the total participating sample) (7 % of students were absent on the day of testing due to illness or school excursion and therefore did not complete the survey at T1); 339 (89 %) completed the questionnaire at time two (T2) and 277 (73 %) completed the questionnaire at time three (T3). The decline in sample size at T2 and T3 was predominantly due to students changing schools, students being absent from school on the day of testing due to illness or school excursion, and two schools being unable to participate at T3 due to end of year exam commitments. The only variable that attrition was associated with was grade. Students who did not remain in the study past T1 were more likely to be in Grade 10 than in Grade 8 at T1 (χ2 = 5.19, p = .02; 66 % compared to 51 %).

Percentage of missing data at the variable level, for those students who completed data at T1, ranged from 0.3 to 4.5 %. Missing data for students completing data at T2 ranged from 0.3 to 4.2 % and for students completing data at T3, missing data ranged from 0.7 to 4.0 %. Missing data across the three waves, including students who did not complete data at a time point ranged from 7.1 to 30.6 %. Full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation was used as it is considered an optimal approach for handling missing data for latent growth modeling (Cheung 2007). This method uses all available information for each person and has been shown to produce unbiased parameter estimates and standard errors for missing at random data (Acock 2005; Enders and Bandalos 2001).

School Effects

Preliminary analyses, using the linear mixed model procedure in SPSS, were conducted to examine the effects of the data being nested (i.e., students are grouped within different schools) and to examine the possibility of a lack of independence of responses arising from students belonging to the same school. Clustering of responses within schools was examined by fitting a random intercept model for each variable and entering school as a random factor. The variance of the random school factor did not significantly differ from zero for any of the analyses. Clustering within schools was therefore not accounted for in subsequent analyses.

Results

Means, standard deviations and correlations between alcohol use, moral disengagement and alcohol use are presented in Table 1.

Unconditional Growth Models

The latent growth model presented in Fig. 1 was estimated and found to fit the data well for alcohol use, moral disengagement and anticipated social outcomes (see Table 2, unconditional models). As depicted in Table 3, for each growth curve the means of the latent factors showed significant intercepts and significant increasing linear slopes indicating that mean rates of alcohol use, moral disengagement and anticipated social outcomes increased across time. Significant variance for the intercept and linear slopes revealed that respondents differed in their initial alcohol use, moral disengagement, and anticipated social outcomes (see Table 2). For alcohol use and moral disengagement, the linear and intercept latent variables were significantly negatively correlated (z = −3.37, p < .001; z = −2.12, p = .034). Adolescents with higher initial alcohol use showed smaller increases in alcohol use over time. Similarly, adolescents with higher underage drinking disengagement showed smaller increases in underage drinking disengagement over time.

Conditional Growth Models

After the unconditional models were tested, gender and age were added as predictors of the intercept and slope. The model with age and gender as predictors of the intercept and slope provided excellent fit to the data (see Table 2, conditional models). For the conditional model for alcohol use, there were significant differences in the intercept by age (b = .79, SE = .13, p < .001), but not by gender (b = −.07, SE = .26, p = .794). Older students reported higher T1 alcohol use scores than younger students. Age did not significantly predict the slope (b = −.13, SE = .07, p = .079). However, females showed smaller increases in alcohol use scores over time relative to males (b = −.49, SE = .15, p < .001). For moral disengagement, there were no significant differences by age or gender on the intercept or slope. For anticipated social outcomes, older students reported higher T1 anticipated social outcomes scores than younger students (b = .39, SE = .10, p < .001) and females reported lower anticipated social outcomes scores at T1 relative to males (b = −.73, SE = .20, p < .001). There was no significant difference for the slope by age or gender.

Parallel Process Latent Growth Models

The latent growth models indicated significant growth in alcohol use, underage drinking disengagement and anticipated social outcomes from peers over time. The significant grade and gender effects found in the previous step were included for all subsequent models.

Alcohol Use and Moral Disengagement

The initial model nearly obtained model fit, χ 2(4, N = 382) = 43.46, p < .001, CFI = .97, TLI = .93, RMSEA = .064. Modification indices, indicated improvement to the model if the T2 UDDS and alcohol use errors were allowed to correlate and allowing gender to predict the UDDS intercept (see Fig. 2). With the inclusion of this modification the model achieved adequate fit to the data (see Table 2). The intercepts (Est = 12.17, SE = 1.71, r = .49, p < .001) and slopes (Est = 2.37, SE = 0.45, r = .46, p < .001) for alcohol use and moral disengagement were significantly correlated. There was also a significant negative relationship between the underage drinking disengagement intercept and alcohol use slope (b = −.02, SE = .01, p = .027) and between the alcohol use intercept and underage drinking disengagement slope (b = −.35, SE = .18, p = .046). This negative relationship does not indicate that initially high moral disengagement predicted a decrease in alcohol use over time (or vis versa). Growth in moral disengagement was consistently positively related to growth in alcohol use, the negative relationship described above indicates that the rate of this growth varied between low and high levels of moral disengagement. High initial levels of moral disengagement related to slower positive growth in alcohol use over the three time points, and low initial levels of moral disengagement related to a steeper positive growth in alcohol use.

Alcohol Use and Anticipated Social Outcomes

The initial model achieved adequate fit to the data (see Table 2). The intercepts (Est = 1.68, SE = 0.26, r = .51, p < .001) and slopes (Est = 0.33, SE = 0.76, r = .52, p < .001) for both growth curves were significantly correlated. There was also a significant negative relationship between the anticipated social outcomes intercept and the alcohol use slope (b = −.16, SE = .06, p = .009), indicating a positive but decelerating relationship between initial anticipated social outcomes and changes in alcohol use over time. The path between the alcohol use intercept and anticipated social outcomes slope was not significant (b = −.00, SE = .03, p = .980). This model achieved slightly better fit, as assessed by the BCC and AIC, than the alcohol use and moral disengagement model.

Moral Disengagement and Anticipated Social Outcomes

The model achieved adequate fit to the data, χ 2(19, N = 382) = 29.22, p = .063, CFI = .99, TLI = .97, RMSEA = .038, and model fit was improved when the non-significant correlation between the intercept and slope for moral disengagement was removed from the model (see Table 2). The intercepts (Est = 10.84, SE = 1.39, r = .68, p < .001) and slopes (Est = 2.17, SE = 0.42, r = .79, p < .001) for anticipated social outcomes and moral disengagement were highly correlated. There was also a significant negative relationship between the anticipated social outcomes intercept and the underage drinking disengagement slope (b = −1.11, SE = .32, p < .001). The path between the alcohol use intercept and anticipated social outcomes slope was not significant (b = −.00, SE = .01, p = .819).

Alcohol Use, Moral Disengagement and Anticipated Social Outcomes

The three latent growth models were combined into a single model, with only significant paths from previous models included. The model attained adequate fit (see Table 2), Consistent with the previous models all the intercepts were positively correlated with each other (alcohol—UDDS = .52; alcohol—ASO = .50; UDDS—ASO = .67) and the slopes were also significantly positively correlated (alcohol—UDDS = .63; alcohol—ASO = .44; UDDS—ASO = .75). The only significant path from an intercept to slope was for anticipated social outcomes to moral disengagement (b = −1.09, SE = .40, p = .007). A possible reason for this could be high collinearity between anticipated social outcomes and moral disengagement. To examine this potentiality, two analyses were conducted. In the first, the non-significant path from the intercept of anticipated social outcomes to the slope of alcohol use was set to zero. This model achieved adequate fit to the data (see Table 2). The path from the intercept of anticipated social outcomes to the slope of moral disengagement remained significant (b = −1.05, SE = .30, p < .001), and the path from the intercept of moral disengagement to the slope of alcohol use became significant (b = −0.02, SE = .01, p = .022). In the second analysis conducted, the non-significant path from the intercept of moral disengagement to the slope of alcohol use was set to zero. This model also achieved adequate fit to the data (see Table 2). The path from the intercept of anticipated social outcomes to the slope of moral disengagement remained significant (b = −1.12, SE = .31, p < .001), and the path from the intercept of anticipated social outcomes to the slope of alcohol use became significant (b = −0.16, SE = .01, p = .006). The path from initial alcohol use to the slope of moral disengagement remained non-significant in both analyses. When comparing models, as assessed by the BCC and AIC, the second modification had lower scores, and therefore better fit than the original model or the first adjusted model.

Discussion

Adolescent alcohol use is commonly associated with other transgressive behaviors including aggression, violence and delinquent conduct (Arbeit et al. 2014; Eaton et al. 2012; McAtamney and Morgan 2009; Scholes-Balog et al. 2013). Although moral processes, including moral disengagement, have been extensively examined in relationship to delinquent and aggressive behavior, these processes have had limited application to underage drinking. It is unclear how moral disengagement, contextualized to underage drinking, changes over time, and how these changes relate to the development of alcohol use during mid-adolescence. It is particularly important to consider moral disengagement, in the context of underage drinking, because unlike other transgressive behaviors, including aggression and delinquent conduct, underage drinking increases with age. Declines that have previously been found for moral disengagement contextualized to delinquent behavior may not necessarily extend to moral disengagement contextualized to underage drinking. Moreover, there is still limited understanding of the social context in which moral disengagement occurs and how social influences, such as anticipated social outcomes from peers impact moral disengagement and adolescent alcohol use across time. In an effort to address these gaps, the current study examined changes in moral disengagement, social outcomes anticipated from peers, and alcohol use over three time-points, 8 months apart, during mid-adolescence. These changes were examined in relationship to key demographic influences: age and gender of the adolescent. Additionally, the interrelationship between moral disengagement, anticipated social outcomes and alcohol use were examined longitudinally using parallel process latent growth modeling.

Consistent with previous epidemiological work and latent growth analyses (Australian Institute of Health & Welfare 2011; Choukas-Bradley et al. 2015; Colder et al. 2014; Duncan et al. 1995; White and Bariola 2012), the unconditional growth models showed that the mean level of alcohol use increased across the three time points, with significant individual variability in the first time point and in the rate of change over time. Similar findings were found for moral disengagement and anticipated social outcomes. It is important to note that the overall prevalence of underage drinking was relatively low, as evidenced by the skewed distribution of the alcohol use measure. The increase in moral disengagement over time contrasted with other studies on moral disengagement contextualized to delinquency and aggression, which found decreases in moral disengagement during mid-adolescence (Paciello et al. 2008; Shulman et al. 2011). Such a contrast in findings highlights the need to consider moral disengagement contextualized to different kinds of transgressive behaviors, showing that, although similar mechanisms may be used to justify or excuse a diverse array of transgressive behavior, changes in the propensity to justify and excuse behavior will not necessarily be uniform across different types of transgressions.

Despite differences in the direction of the trajectory of moral disengagement for underage drinking, consistent with delinquency research (Paciello et al. 2008; Shulman et al. 2011), changes in moral disengagement did positively relate to changes in adolescent alcohol use. What was unexpected was the finding that initial levels of moral disengagement predicted changes in alcohol use and initial levels of alcohol use predicted changes in moral disengagement. Although inconsistent with previous literature (Barchia and Bussey 2011; Sticca and Perren 2015), this finding is not inconsistent with Bandura’s (1986) social cognitive theory, which proposes a bidirectional relationship between personal processes, such as moral disengagement, and behavior. While it is important to consider that moral disengagement predicts adolescent alcohol use, adolescent alcohol use also predicts later moral disengagement. For both these relationships, the pathway was negative, indicating that, although the relationship between the linear slope of moral disengagement and alcohol use was positive, it was a decelerating relationship, which means that individuals with initially low levels of moral disengagement had steeper increases in alcohol use across time compared to those with initially high levels of moral disengagement. This finding is consistent with the correlation between the intercept and the slope for both alcohol use and moral disengagement. As demonstrated in the unconditional models, adolescents with initially low levels of moral disengagement, and low alcohol use, increased their propensity to morally disengage, and consume alcohol, at a faster rate than those with initially high levels of moral disengagement and alcohol use. A possible explanation is that, when they first begin to drink or experiment with alcohol during mid-adolescence, adolescents quite rapidly increase their drinking (Gutman et al. 2011; Henderson et al. 2013). It is possible that, due to legal restrictions and external regulations on adolescent drinking, adolescents have a limited capacity to continually increase the frequency and quantity of alcohol they consume. Both the initial quick progression and external controls on continuously heavier use may explain the steeper incline in justifications for drinking and drinking levels evident for the initially low disengaging and alcohol using group. To explore these possibilities further, future research is needed to investigate the initiation of alcohol use in a younger sample of early adolescents, with a specific focus on moral disengagement contextualized to underage drinking. Moreover, it would be of interest to investigate how external controls may affect changes in alcohol use across adolescence.

A possible explanation for the gradual increasing trajectory in moral disengagement across time is the increase in anticipated social approval from friends for being drunk. The increase in anticipated social outcomes was positively related to increases in moral disengagement across time. There has been considerable evidence indicating that association with deviant peers positively relates to adolescent transgressive behaviors and that much of adolescents’ transgressive behaviors occur within the peer group (Anderson and Brown 2011; Hymel et al. 2010). However, when considering how adolescents morally regulate their behavior and in particular their propensity to justify or excuse transgressive behavior, there has been limited investigation of the peer context in which these justifications occur (Caravita et al. 2014). In this study, it was found that, while initial anticipated social outcomes predicted changes in moral disengagement, initial moral disengagement did not predict changes in anticipated social outcomes. This supports a socialization process, whereby adolescent’s anticipation that their friends will approve of their alcohol use increases the likelihood that adolescents will morally disengage. The high correlations between moral disengagement and anticipated social outcomes across time further highlight the need to consider friendship influences on moral disengagement and the influence of friends on the moral self-regulation of behavior.

When moral disengagement, anticipated social outcomes, and alcohol use were included in a single model, all initial scores, and progression of scores were interrelated. However, the only significant predictive path was between initial levels of anticipated social outcomes and moral disengagement. Part of the reason that neither moral disengagement nor anticipated social outcomes predicted alcohol use in this model may be explained by the high correlations between moral disengagement and anticipated social outcomes. This was supported by further exploratory analyses. When the anticipated social outcomes path was set to zero, the moral disengagement path was significant. Likewise, when the moral disengagement path was set to zero, the anticipated social outcome path was significant. It is important to note that, when comparing models, the model with the significant anticipated social outcome path attained the best fit to the data. Additionally, the parallel analysis between anticipated social outcomes and friends was also a more parsimonious fit to the data than the parallel analysis between moral disengagement and anticipated social outcomes. The strong relationship between anticipated social outcomes and alcohol use is consistent with previous cross-sectional research (Ford and Hill 2012; Kristjansson et al. 2010; Mrug and McCay 2013; Quinn and Bussey 2015b; Shamblen et al. 2014), and further highlights the prominent influence of friends on adolescent alcohol use. Moreover, these findings reinforce the need to consider moral disengagement in the context of social influences.

It should be noted that the high correlations between moral disengagement and anticipated social outcomes identified above were probably accentuated by shared method variance of self-report data. Although Bandura (1986) emphasizes the central role of perception of social consequences on behavior, another way for future research to examine peer influence on moral disengagement and alcohol use without the constraint of share method variance is by considering the modes of influence by which anticipated social outcomes are formed. Bandura (1986) argues that it is by observing the actions of others and outcomes they experience (modeling), by personally experiencing consequences for conduct (enactive experience), and by being informed of the standards for conduct and what outcomes will ensue when particular actions are performed (direct tuition), that adolescents develop their anticipatory outcomes for behavior. Future research may benefit by directly assessing these modes of influence in the friendship group. Already, there is considerable evidence for influence of peer drinking, and peer norms, on adolescent alcohol use (Deutsch et al. 2014, 2014; Eisenberg et al. 2014; Kumar et al. 2002). To enhance an understanding of moral self-regulation, it may be beneficial to examine how peer-reported norms and transgressive conduct influence moral disengagement and how these social influences and moral disengagement jointly influence not just underage drinking but the wide range of transgressive behaviors to which moral disengagement has been applied.

When investigating the influences of age and gender, as expected, at the initial time point older students reported greater alcohol use and anticipated more approval for being drunk than did younger students. However, there was no difference in moral disengagement across age or surprisingly across gender. Males anticipated more positive approval for drunkenness than did females, which is consistent with prior research (Quinn and Bussey 2015b; Cail and LaBrie 2010). Adolescent males and females did not differ in their initial alcohol use; these findings are consistent with evidence of a merging gender gap in adolescents’ experiences with alcohol (Amaro et al. 2001; Hibell et al. 2012). However, adolescent males’ level of alcohol use did increase at a faster rate than that reported by adolescent females, which supports previous findings that adolescent males often escalate into heavy drinkers more than do adolescent females (Li et al. 2001; Mares et al. 2012; Jackson 2013).

The results from this study should be examined in the context of several limitations. Adolescents were asked to retrospectively report the amount of alcohol they had consumed in the previous three-months, which could potentially result in a self-presentation bias and/or a recall bias. However, despite this limitation, self-report data are extensively used and widely accepted as valid, especially when administered in conditions of confidentiality as was done in the current study (Babor et al. 1987; Clark and Winters 2002; Dolcini et al. 1996). Also, students absent on the day of testing due to illness, changing schools, or a school being unable to participate due to exams, did result in sample attrition. Although not optimal, such missing data could be considered missing at random if not completely at random (Acock 2005), and the advantage of LGM was that FIML estimation enabled a maximum number of students to be included in the final sample (Enders and Bandalos 2001). Another limitation that requires consideration is that the current study focused on adolescents who had consumed a least a full standard drink within a school-based population. The findings, therefore, do not necessarily generalize to adolescents experiencing more clinically significant alcohol-related problems.

Conclusions

The current findings extend the extant literature on moral disengagement, particularly moral disengagement in the context of underage drinking. Although moral disengagement has been extensively investigated in the context of a variety of behavioral domains (Bandura et al. 1996; Caprara et al. 2009; Passini 2012; Stanger et al. 2013), much of this research has been cross-sectional and the few longitudinal studies that do exist have focused on moral disengagement contextualized to delinquent or aggressive behavior (Barchia and Bussey 2011; Caravita et al. 2014; Newton et al. 2014; Sticca and Perren 2015). The findings from the current study provide evidence of positive associations between increasing moral disengagement and underage drinking during mid-adolescence. These findings have important implications for interventions. Although this study did not directly assess personal standards for drinking, there is considerable evidence that simply educating adolescents about the legal restrictions on drinking has had minimal, if any, effectiveness in reducing underage drinking (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism 2004/2005). Bandura’s (1986) social cognitive theory and Sykes and Matza’s (1957) neutralization theory posit that, even if social standards for behaviors as articulated in rules and regulations are adopted by adolescents, adolescents may still engage in transgressive behavior, because they have morally disengaged. The strong relationship between moral disengagement and underage drinking suggests that specific targeting of adolescents’ justifications and excuses for underage drinking, and fostering personal responsibility for their use of alcohol may enhance the efficacy of extant intervention programs aimed at reducing adolescents’ alcohol use, particularly when adolescents are initially experimenting with alcohol use. The findings also highlight the importance of considering peer influences on moral disengagement. The consistent relationship between the social outcomes initially anticipated from friends and changes in moral disengagement over time suggest that adolescents may be particularly vulnerable to justifying and excusing their underage drinking when they anticipate approval from their friends for their alcohol use. Moreover, the positive relationship between friends’ approval for drinking and adolescent alcohol use further reinforces the need for interventions to target not only individual processes, including moral disengagement, but also the social context in which underage drinking, or transgressive behavior occurs.

References

Aas, H., & Klepp, K. (1992). Adolescents’ alcohol use and perceived norms. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 33, 315–325. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9450.1992.tb00920.x.

Abar, C. C., Jackson, K. M., & Wood, M. (2014). Reciprocal relations between perceived parental knowledge and adolescent substance use and delinquency: The moderating role of parent–teen relationship quality. Developmental Psychology, 50, 2176–2187. doi:10.1037/a0037463.

Acock, A. C. (2005). Working with missing values. Journal of Marriage & Family, 67, 1012–1028. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00191.x.

Ajzen, I. (2005). Attitudes, personality and behavior (2nd ed.). Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Allen, M., Donohue, W. A., Griffin, A., Ryan, D., & Turner, M. M. (2003). Comparing the influence of parents and peers on the first choice to use drugs. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 30, 163–186. doi:10.1177/0093854802251002.

Allen, J. P., Chango, J., Szwedo, D., Schad, M., & Marston, E. (2012). Predictors of susceptibility to peer influence regarding substance use in adolescence. Child Development, 83, 337–350. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01682.x.

Amaro, H., Blake, S. M., Schwartz, P. M., & Flinchbaugh, L. J. (2001). Developing theory based substance abuse prevention programs for young adolescent girls. Journal of Early Adolescence, 21, 256–293. doi:10.1177/0272431601021003002.

Anderson, K. G., & Brown, S. A. (2011). Middle school drinking: Who, where, and when. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 20, 48–62. doi:10.1080/1067828X.2011.534362.

Arbeit, M. R., Johnson, S. K., Champine, R. B., Greenman, K. N., Lerner, J. V., & Lerner, R. M. (2014). Profiles of problematic behaviors across adolescence: Covariations with indicators of positive youth development. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43, 971–990. doi:10.1007/s10964-014-0092-0.

Arbuckle, J. L. (2012). IBM SPSS Amos 21 users guide. Crawfordville: Amos Development Corporation.

Australian Institute of Health & Welfare. (2011). 2010 National Drug Strategy Household Survey (Drug Statistics Series No. 25. Cat. No. PHE 145).

Babor, T. F., Stephens, R. S., & Marlatt, G. A. (1987). Verbal report methods in clinical research on alcoholism: Response bias and its minimization. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 48, 410–424.

Bahr, S. J., Hoffmann, J. P., & Yang, X. (2005). Parental and peer influences on the risk of adolescent drug use. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 26, 529–551. doi:10.100/s10935-005-0014-8.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought & action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. (2002). Selective moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. Journal of Moral Education, 13, 101–119. doi:10.1080/0305724022014322.

Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., & Pastorelli, C. (1996). Mechanisms of moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2, 364–374. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.71.2.364.

Barchia, K., & Bussey, K. (2011). Individual and collective social cognitive influences on peer aggression: Exploring the contribution of aggression efficacy, moral disengagement, and collective efficacy. Aggressive Behavior, 37, 107–120. doi:10.1002/ab.20375.

Barriga, A. Q., & Gibbs, J. C. (1996). Measuring cognitive distortion in antisocial youth: Development and preliminary validation of the “how I think” questionnaire. Aggressive Behavior, 22, 333–345. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2337(1996)22:5<333:AID-AB2>3.0.CO;2-K.

Bava, S., & Tapert, S. F. (2010). Adolescent brain development and the risk for alcohol and other drug problems. Neuropsychology Review, 20, 398–413. doi:10.1007/s11065-010-9146-6.

British Columbia Ministry of Health Services (2010). Health minds, healthy people—A ten-year plan to address mental health & substance use in British Columbia. Retrieved from http://www.health.gov.bc.ca/library/publications/year/2010/healthy_minds_healthy_people.pdf-268k-2011-12-14.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Cail, J., & LaBrie, J. W. (2010). Disparity between the perceived alcohol-related attitudes of parents and peers increases alcohol risk in college students. Addictive Behaviors, 35, 135–139. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.09.019.

Caprara, G. V., Fida, R., Vecchione, M., Tramontano, C., & Barbaranelli, C. (2009). Assessing civic moral disengagement: Dimensionality and construct validity. Personality and Individual Differences, 47, 504–509. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2009.04.027.

Caprara, G. V., Tisak, M. S., Alessandri, G., Fontaine, R. G., Fida, R., & Paciello, M. (2014). The contribution of moral disengagement in mediating individual tendencies toward aggression and violence. Developmental Psychology, 50, 71–85. doi:10.1037/a0034488.

Caravita, S. C. S., Sijtsema, J. J., Rambaran, J. A., & Gini, G. (2014). Peer influences on moral disengagement in late childhood and early adoelscence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43, 193–207. doi:10.1007/s10964-013-9953-1.

Cheung, M. W. (2007). Comparison of methods of handling missing time-invariant covariates in latent growth models under the assumption of missing completely at random. Organizational Research Methods, 10, 609–634. doi:10.1177/1094428106295499.

Chi-mei, J. (2008). Neutralization techniques, crime decision-making and juvenile thieves. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 14, 251–265. doi:10.1080/02673843.2008.9748006.

Choukas-Bradley, S., Giletta, M., Neblett, E. W., & Prinstein, M. J. (2015). Ethnic differences in associations among popularity, likability, and trajectories of adolescents’ alcohol use and frequency. Child Development, 86, 519–535. doi:10.1111/cdev.12333.

Clark, D. B., & Winters, K. M. (2002). Measuring risks and outcomes in substance use disorders prevention research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70, 1207–1223. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.70.6.1207.

Clark, D. B., Thatcher, D. L., & Tapert, S. F. (2008). Alcohol, psychological dysregulation, and adolescent brain development. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 32, 375–385. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00601.x.

Colder, C. R., O’Connor, R. M., Read, J. P., Eiden, R. D., Lengua, L. J., Hawk, L. W., & Wieczorek, W. F. (2014). Growth trajectories of alcohol information processing and associations with escalation of drinking in early adolescence. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 28, 659–670. doi:10.1037/a0035271.

Collins, W. A., Maccoby, E. E., Steinburg, L., Hetherington, E. M., & Bornstein, M. H. (2000). Contemporary research on parenting: The case for nature and nurture. American Psychologist, 55, 218–232. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.2.218.

Connolly, E. J., Schwartz, J. A., Nedelec, J. L., Beaver, K. M., & Barnes, J. C. (2015). Different slopes for different folks: Genetic influences on growth in delinquent peer association and delinquency during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44, 1413–1427. doi:10.1007/s10964-015-0299-8.

Crews, F., He, J., & Hodge, C. (2007). Adolescent cortical development: A critical period of vulnerability for addiction. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior, 86, 189–199. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2006.12.001.

Danielsson, A., Wennberg, P., Tengstrom, A., & Romelsjo, A. (2010). Adolescent alcohol use trajectories: Predictors and subsequent problems. Addictive Behaviors, 35, 848–852. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.05.001.

Detert, J. R., Trevino, L. K., & Sweitzer, V. L. (2008). Moral disengagement in ethical decision making: A study of antecedents and outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 374–391. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.93.2.374.

Deutsch, A. R., Steinley, D., & Slutske, W. S. (2014). The role of gender and friends’ gender on peer socialization of adolescent drinking: A prospective multilevel social network analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43, 1421–1435. doi:10.1007/s10964-013-0048-9.

Dodder, R. A., & Hughes, S. P. (1993). Neutralization of drinking behavior. Deviant Behavior, 14, 65–79.

Dolcini, M. M., Adler, N. E., & Ginsberg, D. (1996). Factors influencing agreement between self-reports & biological measures of smoking among adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 6, 515–542.

Donaldson, L. J. (2010). Annual report of the Chief Medical Officer 2009. UK: Crown.

Duncan, T. E., & Duncan, S. C. (2004). An introduction to latent growth modeling. Behavior Therapy, 35, 333–363. doi:10.1016/S0005-7894(04)80042-X.

Duncan, T. E., Tildesley, E., Duncan, S. C., & Hops, H. (1995). The consistency of family and peer influences on the development of substance use in adolescence. Addiction, 90, 1647–1660. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1995.tb02835.x.

Duncan, S. C., Duncan, T. E., & Strycker, L. A. (2000). Risk and protective factors influencing adolescent problem behavior: A multivariate latent growth curve analysis. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 22, 103–109. doi:10.1007/BF02895772.

Eaton, D. K., Kann, L., Kinchen, S., Shanklin, S., Flint, K. H., Hawkins, J., & Wechsler, H. (2012). Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Surveillance Summary, 61(4), 1–162. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2006.00127.x.

Eisenberg, M. E., Toumbourou, J. W., Catalano, R. F., & Hemphill, S. A. (2014). Social norms in the development of adolescent substance use: A longitudinal analysis of the International Youth Development Study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43, 1486–1497. doi:10.1007/s10964-014-0111-1.

Enders, C. K., & Bandalos, D. L. (2001). The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. In Educational psychology papers and publications. Paper 64. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/edpsychpapers/64.

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Ford, J. A., & Hill, T. D. (2012). Religiosity and adolescent substance use: Evidence from the national survey on drug use and health. Substance Use and Misuse, 47(787–798), 1082. doi:10.3109/6084.2012.667489.

Gini, G., Pozzoli, T., & Hymel, S. (2014). Moral disengagement among children and youth: A meta-analytic review of links to aggressive behavior. Aggressive Behavior, 9999, 1–13. doi:10.1002/ab.21502.

Gutman, L. M., Eccles, J. S., Peck, S., & Malanchuk, O. (2011). The influence of family relations on trajectories of cigarette and alcohol use from early to late adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 34, 119–128. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.01.005.

Guttmannova, K., Bailey, J. A., Hill, K. G., Lee, J. O., Hawkins, J. D., Woods, M. L., & Catalano, R. F. (2011). Sensitive periods for adolescent alcohol use initiation: Predicting the lifetime occurrence and chronicity of alcohol problems in adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 72, 221–231.

Hardy, S. A., Bean, D. S., & Olsen, J. A. (2015). Moral identity and adolescent prosocial and antisocial behaviors: Interactions with moral disengagement and self-regulation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44, 1542–1554. doi:10.1007/s10964-014-0172-1.

Henderson, H., Nass, L., Payne, C., Phelps, A., & Ryley, A. (2013). Smoking, drinking and drug use among young people in England in 2012. Leeds, UK: Health & Social Care Information Centre.

Hibell, B., Guttormson, U., Ahlström, S., Balakireva, O., Bjarnason, T., Kokkevi, A., & Kraus, L. (2012). The 2011 ESPAD report: Substance use among students in 36 European countries. Stockholm, Sweden: The Swedish Council for Information on Alcohol and Other Drugs.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118.

Hughes, S. P., & Dodder, R. A. (1983). Alcohol-related problems and collegiate drinking patterns. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 12, 65–76.

Hymel, S., Schonert-Reichl, K. A., Bonanno, R. A., Vaillancourt, T., & Henderson, N. R. (2010). Bullying and morality: Understanding how good kids can behave badly. In S. R. Jimerson, S. M. Swearer, & D. L. Espelage (Eds.), Handbook of bullying in schools: An international perspective (pp. 101–118). New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Jackson, K. (2013). Alcohol use during the transition from middle school to high school: National panel data on prevalence & moderators. Developmental Psychology,. doi:10.1037/a0031843.

Jacobs, B. A., & Copes, H. (2015). Neutralization without drift: Criminal commitment among persistent offenders. British Journal of Criminology, 55, 286–302. doi:10.1093/bjc/azu100.

Jarvinen, M., & Demant, J. (2011). The normalisation of cannabis use among young people: Symbolic boundary work in focus groups. Health, Risk and Society, 13, 165–182. doi:10.1080/13698575.2011.556184.

Johnston, L. D., O’Malley, P. M., Miech, R. A., Bachman, J. G., & Schulenberg, J. E. (2015). Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use 1975–2014: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan.

Kandel, D. B. (1978). Homophily, selection and socialization in adolescent friendships. American Journal of Sociology, 84, 427–436.

Kobin, M. (2013). Making sense of risk: Young Estonians drink-driving. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 20, 473–481. doi:10.3109/09687637.2013.767319.

Kristjansson, A. L., Sigfusdottir, I. D., James, J. E., Allegrante, J. P., & Helgason, A. R. (2010). Perceived parental reactions and peer respect as predictors of adolescent cigarette smoking & alcohol use. Addictive Behaviors, 35, 256–259. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.10.002.

Kumar, R., O’Malley, P. M., Johnston, L. D., Schulenberg, J. E., & Bachman, J. G. (2002). Effects of school-level norms on student substance use. Prevention Science, 3, 105–124. doi:10.1023/A:1015431300471.

Li, F., Duncan, T. E., Mcauley, E., Harmer, P., & Smolkowski, K. (2000). A Didactic example of latent curve analysis applicable to the study of aging. Journal of Aging & Health, 12, 388–425. doi:10.1177/089826430001200306.

Li, F., Duncan, T. E., Duncan, S. C., & Hops, H. (2001). Piecewise growth mixture modeling of adolescent alcohol use data. Structural Equation Modeling, 8, 175–204. doi:10.1207/S15328007SEM0802_2.

Light, J. M., Greenan, C. C., Rusby, J. C., Nies, K. M., & Snijders, T. A. B. (2013). Onset to first alcohol use in early adolescence: A network diffusion model. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 23, 487–499. doi:10.1111/jora.12064.

Lucidi, F., Zelli, A., Mallia, L., Grano, C., Russo, P. M., & Violani, C. (2008). The social-cognitive mechanisms regulating adolescents’ use of doping substances. Journal of Sports Science, 26, 447–456. doi:10.1080/02640410701579370.

Mares, S. H. W., Lichtwarck-Aschoff, A., Burk, W. J., Van der Vorst, H., & Engels, R. C. M. E. (2012). Parental alcohol-specific rules and alcohol use from early adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53, 798–805. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02533.x.

McArdle, J. J. (1988). Dynamic but structural equation modeling of repeated measures data. In R. B. Cattell & J. Nesselroade (Eds.), Handbook of multivariate experimental psychology (2nd ed., pp. 561–614). New York: Plenum Press.

McAtamney, A., & Morgan, A. (2009). Key issues in antisocial behavior. In Research in Practice no. 5. Retrieved from Australian Institute of Criminology website: http://www.aic.gov.au/.

McBride, N., Farringdon, F., Meuleners, L., & Midford, R. (2006). School health and alcohol harm reduction project: Details of intervention development and research procedures. Perth, WA: National Drug Research Institute, Curtin University of Technology.

Meredith, W., & Tisak, J. (1990). Latent curve analysis. Psychometrika, 55, 107–122. doi:10.1007/BF02294746.

Mrug, S., & McCay, R. (2013). Parental and peer disapproval of alcohol use and its relationship to adolescent drinking: Age, gender, and racial differences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 27, 604–614. doi:10.1037/a0031064.

Musher-Eizenman, D. R., Holub, S. C., & Arnett, M. (2003). Attitude and peer influences on adolescent substance use: The moderating effect of age, sex, and substance. Journal of Drug Education, 33, 1–23. doi:10.2190/YED0-BQA8-5RVX-95JB.

National Health & Medical Research Council. (2009). Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol. Retrieved from http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_filesnhmrc/.

National Institute of Alcohol Abuse & Alcoholism. (2004/2005). Alcohol and development in youth: A multidisciplinary overview. Alcohol Research and Health, 28, 104–176. Retrieved from http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/arh283/toc28-3.htm.

Newton, N. C., Havard, A., & Teesson, M. (2012). The association between moral disengagement, psychological distress, resistive self-regulatory efficacy and alcohol and cannabis use among adolescents in Sydney, Australia. Addiction Research & Theory, 20, 261–269. doi:10.3109/16066359.2011.614976.

Newton, N. C., Barrett, E. L., Swaffield, L., & Teesson, M. (2014). Risky cognitions associated with adolescent alcohol misuse: Moral disengagement, alcohol expectancies and perceived self-regulatory efficacy. Addictive Behaviors, 39, 165–172. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.09.030.

Paciello, M., Fida, R., Tramontano, C., Lupinet, C., & Caprara, G. V. (2008). Stability and change of moral disengagement and its impact on aggression and violence in late adolescence. Child Development, 79, 1288–1309. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01189.x.

Passini, S. (2012). The delinquency-drug relationship: The influence of social reputation and moral disengagement. Addictive Behaviors, 37, 577–579. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.01.012.

Perkins, H. W. (2003). The emergence and evolution of the social norms approach to substance abuse prevention. In H. W. Perkins (Ed.), The social norms approach to preventing school and college age substance abuse: A handbook for educators, counselors, clinicians (pp. 3–18). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Piacentini, M. G., Chatzidakis, A., & Banister, E. N. (2012). Making sense of drinking: The role of techniques of neutralisation and counter-neutralisation in negotiating alcohol consumption. Sociology of Health & Illness, 34, 841–857. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9566.2011.01432.x.

Pitkänen, T., Kokko, K., Lyyra, A., & Pulkkinen, L. (2008). A developmental approach to alcohol drinking behavior in adulthood: A follow-up study from age 8 to age 42. Addiction, 103(Suppl. 1), 48–68. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02176.x.

Quinn, C. A., & Bussey K. (2015a). The role of moral disengagement in underage drinking and heavy episodic drinking. Substance Use & Misuse. doi:10.3109/10826084.2015.1018541.

Quinn, C. A., & Bussey, K. (2015b). Adolescents’ anticipated social outcomes from mother, father and peers for drinking alcohol and being drunk. Addiction & Research Theory, 23, 253–264. doi:10.3109/16066359.2015.1014346.

Reboussin, B. A., Song, E., Shrestha, A., Lohman, K. K., & Wolfson, M. (2006). A latent class analysis of underage problem drinking: Evidence from a community sample of 16–20 year olds. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 83, 199–209. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.11.013.

Ribeaud, D., & Eisner, M. (2010). Are moral disengagement, neutralization techniques, and self-serving cognitions the same? Developing a unified scale of moral neutralization of aggression. International Journal of Conflict and Violence, 4, 298–315.

Ryan, S. M., Jorm, A. F., & Lubman, D. I. (2010). Parenting factors associated with reduced adolescent alcohol use: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 44, 774–783. doi:10.1080/00048674.2010.501759.

Scholes-Balog, K. E., Hemphill, S. A., Kremer, P., & Toumbourou, J. W. (2013). A longitudinal study of the reciprocal effects of alcohol use and interpersonal violence among Australian young people. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42, 1811–1823. doi:10.1007/s10964-013-9910-z.

Shamblen, S. R., Ringwalt, C. L., Clark, H. K., & Hanley, S. M. (2014). Alcohol use growth trajectories in young adolescence: Pathways and predictors. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse, 23, 9–18. doi:10.1080/1067828X.2012.747906.

Shields, I. W., & Whitehall, G. C. (1994). Neutralization and delinquency among teenagers. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 21, 223–235.

Shulman, E. P., Cauffman, E., Piquero, A. R., & Fagan, J. (2011). Moral disengagement among serious juvenile offenders: A longitudinal study of the relations between morally disengaged attitudes and offending. Developmental Psychology, 47, 1619–1632. doi:10.1037/a0025404.

Sijtsema, J. J., Rambaran, J. A., Caravita, S. C. S., & Gini, G. (2014). Friendship selection and influence in bullying and defending: Effects of moral disengagement. Developmental Psychology, 50, 2093–2104. doi:10.1037/a0037145.

Simons-Morton, B. (2004). Prospective association of peer influence, school engagement, drinking expectancies, and parental expectations with drinking initiation among sixth graders. Addictive Behaviors, 29, 299–309. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.005.

Smith, A. M. A., & Rosenthal, D. A. (1995). Adolescents’ perceptions of their risk environment. Journal of Adolescence, 18, 229–245. doi:10.1006/jado.1995.1016.

Stanger, N., Kavussanu, M., Boardley, I. D., & Ring, C. (2013). The influence of moral disengagement and negative emotion on antisocial sport behavior. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 2, 117–129. doi:10.1037/a0030585.

Sticca, F., & Perren, S. (2015). The chicken and the egg: Longitudinal associations between moral deficits and bullying. A parallel process latent growth model. Merril Palmer Quarterly, 61, 85–100.

Sykes, G. M., & Matza, D. (1957). Techniques of neutralization: A theory of delinquency. American Sociological Review, 22, 664–670.