Abstract

The model minority image is a common and pervasive stereotype that Asian American adolescents must navigate. Using multiwave data from 159 adolescents from Asian American backgrounds (mean age at initial recruitment = 15.03, SD = .92; 60 % female; 74 % US-born), the current study targeted unexplored aspects of the model minority experience in conjunction with more traditionally measured experiences of negative discrimination. When examining normative changes, perceptions of model minority stereotyping increased over the high school years while perceptions of discrimination decreased. Both experiences were not associated with each other, suggesting independent forms of social interactions. Model minority stereotyping generally promoted academic and socioemotional adjustment, whereas discrimination hindered outcomes. Moreover, in terms of academic adjustment, the model minority stereotype appears to protect against the detrimental effect of discrimination. Implications of the complex duality of adolescents’ social interactions are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The model minority image of Asian Americans as hardworking overachievers was formally labeled over a half century ago (Peterson 1966), and it continues to persist in today’s social milieu. The image itself is a common one that both Asians and non-Asians alike, from adolescents to adults, are acutely aware (Oyserman and Sakamoto 1997; Wong and Halgin 2006). Direct experiences are pervasive, with research showing that over 99 % of Asian American adolescents have had at least one encounter in which they felt like they were being stereotyped as a model minority (Thompson and Kiang 2010). Yet, despite its prevalence and commonality, the developmental implications of the model minority stereotype are not well-understood. Most of the existing research has been conceptual, with the overwhelming majority of perspectives emphasizing that the stereotype confers negative youth outcomes (Suzuki 2002). However, some work shows that a sizable portion of Asian Americans view the model minority image as a positive phenomenon, and stereotyping experiences have sometimes been correlated with adaptive outcomes (Shih et al. 1999; Thompson and Kiang 2010; Whaley and Noel 2013). Another gap in the literature is reflected in the idea that research has yet to differentiate model minority stereotyping experiences from more traditionally measured indicators of negative discrimination. By considering model minority experiences in conjunction with discrimination, which has tended to dominate the literature, we aim to shed light on the model minority image and better understand its impact on development, for better or for worse.

The Model Minority Image of Asian American Youth

The model minority image paints a portrait of Asian Americans that connotes generally positive intrinsic talents and characteristics. The image is often associated with academics, for example, with Asian Americans viewed as particularly skilled in science, math, and music, as studious individuals who throw off the grading curve, or as quiet students that teachers and other school staff admire and respect (Chang and Demyan 2007; Cocchiara and Quick 2004). However, the range of stereotypes that are associated with the image is complex and multifaceted, with some generalizations also focusing on psychological and social dimensions that might not be as readily favored (e.g., being socially weak, deferential) (Wong et al. 2012). The historical roots of the image itself date back to the Civil Rights era when the status quo needed a successful exemplar to cast doubt on the validity of existing social disparities that were apparent between the mainstream and ethnic minorities as a whole (Hurh and Kim 1989; Suzuki 2002). As such, the image and associated stereotypes can be damaging to intragroup relations and foster tension between Asian Americans and their non-Asian ethnic minority peers who might feel a sense of resentment towards the wider implications of such relatively favorable views. Over time, the model minority image has persisted and remains an indelible fixture in the race relations that Asian American youth face today.

In light of its contemporary impact, there is a pressing need to better understand adolescents’ stereotyping experiences and how they affect developmental outcomes. Adolescence is a prime period in which to focus an investigation on stereotypes given that the high school years are especially rife with social pressures for youth to both fit in and stand out (Erikson 1968; Fuligni et al. 2008; Niwa et al. 2014). During this period of intense identity development and self-categorization, race-related biases and social comparisons are typically experienced and brought to the fore in adolescents’ daily lives (Rosenbloom and Way 2004). The salience as well as perceived frequency of stereotyping could also increase during the adolescent years as youth develop formal operations and abstract thinking which allows them to reflect more on how they, as a member of a social group, are treated by others (Inhelder and Piaget 1958). As adolescents become more self-aware, and as they also gain independence and accumulate more social experiences, they might become more sensitive to how they are treated by others as well as encounter more opportunities to be seen as a stereotype (Greene et al. 2006; Phinney and Chavira 1995). Yet, this key question of developmental change remains unanswered given that longitudinal examinations of high school students’ reports of the model minority stereotype are critically lacking in the literature.

Much of the existing research on the model minority stereotype has been also limited in its conceptual focus and use of qualitative interviews to gain insight on the experience. In observational and interview studies of Asian American high school students, participants have reported that they feel the model minority image is restrictive, inaccurate, and damaging to social relationships (Lee 1996; Rosenbloom and Way 2004). Their reactions have ranged from active attempts to define themselves in non-stereotypical ways (e.g., de-emphasizing school to resist achievement stereotypes) to greater bonding with ethnic minority peers over their unfortunate common ground of negative discrimination. While such knowledge from existing work has been rich and informative, few studies have systematically quantified adolescents’ reports of the prevalence of these experiences or tracked changes in prevalence over time.

Model Minority Stereotyping and Discrimination Experiences

To understand the full implications of being stereotyped as a model minority, it is important to also examine the simultaneous influence of more negative forms of discrimination, particularly since Asian Americans have been found to report more discrimination compared to their peers from other ethnic groups (Huynh and Fuligni 2010). There is much conceptual overlap between stereotyping and discrimination. Loosely defined as biased actions or behaviors toward an individual due to his or her group membership, discrimination typically involves negative actions or behaviors (Fishbein 1996). For instance, in many well-known measures of discrimination, including the one used in the current study, individuals are asked about discriminatory experiences that involve unfair treatment, being disliked by others, and being threatened or harassed (e.g., Greene et al. 2006). Although encounters with the model minority stereotype could be also characterized by experiences such as unfair treatment and bias, the nature of stereotyping tends to more distinctly involve basic assumptions and attitudes. In the case of the model minority image, these assumptions tend to be more trait-based and positive on the surface (e.g., talented in classical music, good at science and math, hardworking). Hence, model minority stereotyping and discrimination can be seen to share a foundation which stems from race-related generalizations and potential bias. However, our conceptualization of these experiences involves nuanced distinctions in that stereotyping focuses on attitudes and others’ assumptions that are mostly related to more positively-connoted characteristics, whereas discrimination is more behaviorally-based and encompasses negative assumptions from others and more inherently oppositional tones.

By including both model minority stereotyping and negative discrimination in the same study, we can move the field forward by examining whether these experiences are directly related to each other. To our knowledge, no research has systemically investigated these links; however, some of the literature on perceived discrimination cites teacher favoritism and other positive societal perceptions as a major source of bullying and negative attitudes towards Asian Americans as perpetrated by African American and Latin American peers (Liang et al. 2007; Qin et al. 2008; Rosenbloom and Way 2004). Hence, these experiences could be correlated in that the stereotype itself could serve as an impetus for the negative, biased treatment that is reflected through discrimination (Niwa et al. 2011). Moreover, experiences of negative discrimination could make youth more aware of other forms of ethnic stereotyping, and vice versa. We aimed to shed light on this important issue by tracking adolescents’ perceptions of both model minority stereotyping and negative discrimination experiences over time. Although it is possible that these ethnic interactions represent completely separate phenomena and are largely independent from each other, we expected that perceptions of stereotyping and discrimination experiences would be associated with each other given their conceptual and likely experiential overlap.

Model Minority Stereotyping, Discrimination, and Links to Adjustment

Beyond illuminating the reported rates and normative progression of model minority stereotyping experiences, as well as how such experiences might be linked with discrimination, another primary goal of the present study was to examine implications for adolescent adjustment. At a surface level, the feeling of being pigeonholed and seen as a broad group rather than as an individual can be restrictive, and abundant literature points to the limiting and detrimental effects of the model minority stereotype (Wang et al. 2011). Views of Asian Americans as a model minority can create pressure for youth to live up to the image, and create unrealistic and inaccurate expectations (Wong and Halgin 2006). Consistent with the literature on stereotype threat, some experimental work has shown that the model minority stereotype can cause people to “choke” and perform poorly on a test due to the burden of actually meeting the expectations (Cheryan and Bodenhausen 2000; Shih et al. 2002). In the case of Asian Americans being stereotyped as overachievers who are successful in academics, the generalized perceptions also can be wholly inaccurate and, as such, prevent some youth from receiving much needed educational help or support (Ho and Jackson 2001; Ngo and Lee 2007; Suzuki 2002; Wong and Halgin 2006; Wu 2002). Recent work has indeed illustrated that the image of Asian Americans as high achievers is largely a myth and that some youth, particularly those with Southeast Asian ancestry, are doing quite poorly in school (Asian American Federation 2014). Moreover, in the face of presumed academic success, Asian American youth’s socioemotional struggles or negative experiences with discrimination and other stressors might be overlooked (Niwa et al. 2011). Damaging effects of the model minority stereotype on a number of different dimensions of adjustment might therefore be expected, particularly during adolescence when social stressors and academically-based stereotypes are especially salient.

However, there could be benefits to being stereotyped in a relatively positive manner. Drawing on qualitative responses, several studies have found that a considerable proportion of Asian American youth feel that the model minority image is valuable and worthy of pride (Oyserman and Sakamoto 1997; Thompson and Kiang 2010). Akin to the self-fulfilling prophesy, as well as symbolic interactionist perspectives (Harter 1999; Rosenthal and Jacobson 1968), it can be advantageous and constructive if one is cast in a positive light. Some research has found that activating the model minority stereotype prior to a test can even lead to a performance boost among Asian American young adults as well as children (Ambady et al. 1999, 2001). If others in society hold positive interpretations of one’s behaviors and favorable views of the self, one can internalize such attitudes and incorporate them into one’s own positive self-evaluations.

Taken together, there is competing evidence for both positive and negative offshoots of the model minority experience and clearly more work needs to be done. One way that the current study clarifies prior conceptual and empirical work on the model minority stereotype’s role in adolescent development is by including a range of outcomes to examine the possibility that stereotyping experiences might benefit certain outcomes while hindering others. In support of this approach, recent work suggests that the underlying interpretation of the model minority is not wholly positive. For instance, although a generally favorable image of the model minority centers on achievement orientation and academic success, another aspect of the stereotype is embodied by the myth of unrestricted mobility in which Asian Americans are presumed to experience less racism and barriers relative to other racial groups (Yoo et al. 2010). Other studies have also found the MMS to comprise stereotypes of social behavior that might be interpreted as more negative or demeaning (e.g., quiet, humble; Oyserman and Sakamoto 1997). Consistent with the perspective that the model minority stereotype captures and potentially affects different domains of development in different ways, we investigated academic adjustment outcomes (e.g., perceived academic performance, valuing of school), psychological well-being outcomes (e.g., self-esteem, depressive symptoms), as well as adolescents’ positive relationships with others. Despite some of the counter evidence that exists (Shih et al. 2002; Wang et al. 2011), we drew on theories of symbolic interactionism and self-development (Harter 1999) and expected that the largely positive attitudes and high expectations about Asian American adolescents’ academic success would be beneficial to adolescents’ lives and contribute to positive academic development. However, given the myth of unrestricted mobility and the social tension that can arise when Asian Americans and their potential successes are triangulated against their peers (Liang et al. 2007; Qin et al. 2008; Yoo et al. 2010), we expected that perceptions of the model minority stereotype would have negative ramifications on psychological adjustment and relationships with others.

Examining the associations between model minority stereotyping and outcomes while simultaneously considering experiences of negative discrimination is a particular strength in our approach. In contrast to the inconsistent evidence for the effects of model minority stereotyping, discrimination’s detrimental effects have been unequivocal. Theoretical perspectives stemming from social stratification theory, Garcia Coll et al.’ (1996) integrative model of child development, and racial identity models (Kim 2001) all point to harmful consequences of unfair treatment and negative attitudes, and empirical work has consistently confirmed these conceptual viewpoints (Huynh and Fuligni 2010; Niwa et al. 2014; Wang and Atwal 2014). In line with this prior conceptual and empirical work, we expected that perceptions of discrimination would be associated with poor adjustment across academic, psychological, and social domains.

However, it is yet unknown whether or how experiences with the model minority stereotype or discrimination are associated with adjustment while controlling for the other; their effects could be independent, or perhaps they exacerbate each other. It is also possible that the positive portrayals of Asian Americans via the model minority image serve to moderate the negative effect of discrimination. Indeed, we expected that, within the academic realm, perceptions of the model minority stereotype would mitigate any negative effects of discrimination on outcomes. In contrast, for psychological and social outcomes, model minority stereotyping and discrimination experiences were expected to work in concert to threaten youth adjustment. By examining both model minority stereotyping and ethnic discrimination in the same study, we can gain important, comprehensive information on how adolescents’ interactions with others in society can shape their developmental trajectories.

The Current Study

The current study had three overarching goals. First, we examined normative changes in Asian American adolescents’ experiences with both the model minority stereotype and discrimination over the high school years. Consistent with some of the empirical research using traditional measures of discrimination (e.g., negative treatment), which has largely documented developmental increases in perceptions (Benner and Graham 2011; Greene et al. 2006; Wang and Atwal 2014), we expected that perceptions of both types of experiences would increase over time. Second, we examined whether model minority stereotyping and discrimination experiences are associated with each other. We expected to find evidence of their interrelatedness, perhaps because the model minority image has been sometimes described as a root cause of discrimination (Liang et al. 2007; Niwa et al. 2014). It is also possible that stereotyping experiences, which are generally more subtle and attitude-based, could be associated with adolescents’ sensitivity and awareness of more negative forms of discrimination and biased behaviors. Third, we examined main and interactive effects of the model minority stereotype and discrimination on a diverse range of adolescent adjustment outcomes. We considered academic (e.g., perceived academic performance, valuing of school) and socioemotional outcomes (e.g., positive relationships, self-esteem, depressive symptoms) to gain a full picture of how adolescents’ lives are shaped by their social interactions with others.

Drawing on the abundant discrimination literature (Greene et al. 2006; Huynh and Fuligni 2010; Wang and Atwal 2014), we expected to find detriments of discrimination on outcomes. However, the expected effects of model minority stereotyping were more nuanced. Consistent with symbolic interactionism (Harter 1999), positive societal views are internalized into adolescents’ self-conceptions and, as such, perspectives of Asian Americans as smart and hardworking were expected to be promotive, particularly in terms of academic adjustment for which the stereotype is especially relevant. Yet, despite the optimistic nature of the stereotype within the academic domain, the experience of being artificially categorized and pigeon-holed can be stressful and create a harmful environment with which to cope, as well as threaten one’s social relationships in the process (Qin et al. 2008; Wong and Halgin 2006). Hence, we did not expect to find positive associations between model minority stereotyping experiences and psychological adjustment or positive relationships with others.

One of the unique strengths of this study was its simultaneous examination of model minority stereotyping and discrimination. In light of the putative positive effects of the model minority image on academic outcomes in particular, the favorable views that accompany the stereotype were expected to counteract adolescents’ negative discriminatory experiences. However, among psychosocial outcomes, stereotyping and discrimination experiences were expected to exacerbate each other. Exploring how both forms of experiences independently and interactively affect different dimensions of adjustment can lead to a more complete and holistic picture of the diverse interpersonal interactions that Asian Americans encounter. Indeed, in reality, adolescents are confronted with nuanced social experiences, and all youth can be portrayed in both a positive and negative light. We aimed to examine the duality of these experiences, how they change and relate to each other over time, and how they exert main and interactive effects on adjustment. Notably, in all of our analyses, we controlled for gender and generational status given prior work showing meaningful associations with adjustment and documenting the need to consider these key demographic variables (Greene et al. 2006; Niwa et al. 2011; Wong et al. 2012; Yoo et al. 2010).

Methods

Participants

At the initial time of recruitment, participants were 180 9th (48.3 %; mean age = 14.43, SD = .64) and 10th graders (mean age = 15.56, SD = .74) from Asian American backgrounds (60 % female). Adolescents were recruited from six public high schools in the Southeastern US. About 74 % was US-born (i.e., second-generation). The remaining 26 % was foreign-born (i.e., first-generation). For those who were foreign-born, age of immigration ranged from 1 to 14 years (M = 5.79, SD = 4.21). An open-ended, self-report item indicated representation from a range of specific ethnic ancestries including: Hmong (28 %), multiethnic (mostly within Asian groups; e.g., Cambodian and Chinese) (22 %), South Asian (e.g., Indian, Pakistani) (11 %), Chinese (8 %), pan-ethnic (i.e., Asian) (8 %), and small clusters such as Montagnard, Laotian, Vietnamese, Filipino/a, Japanese, Korean, and Thai (23 %). Approximately 84 % of the adolescents had parents who were married, 8 % had parents who were divorced, and the remaining 8 % had parents who were separated, never married, or widowed.

Procedure

A stratified cluster design identified public high schools in central North Carolina characterized as having high Asian growth for the state and a student body with relatively large proportions of Asian students (3–10 %). The schools varied in ethnic diversity, achievement, socioeconomic status, and total size. Two schools consisted primarily of White students (80 %), followed by Asian Americans comprising 7–10 % and African American and Latino students constituting smaller minorities (<5 %). White students were also the majority in two additional schools (60 %), with African Americans and Latinos forming 10–20 % of the student body each, and Asian American comprising 3–4 % of the remaining students. African American students formed the majority in the two remaining schools (60–65 %), with Latino and White students comprising the next largest groups (10–20 % each) followed by Asians accounting for 4–6 %. Although differences in study variables might exist as a function of school, our data were not ideal for testing this possibility given that students were not evenly distributed across schools (e.g., one school contained only two participants). Also, we could not test school as a Level 3 variable in our hierarchical models because Level 3 variables with less than 10 units (i.e., schools) can yield unreliable standard errors (Maas and Hox 2005; Snijders 2005).

In small group settings, students identified as Asian through matriculation forms were invited to participate in a study on the social and cultural issues that affect their daily lives. Upon returning parental consent and assent forms during a follow-up visit, participants were administered a packet of questionnaires during school time. The questionnaires took 30–45 min to complete. Approximately 60 % of those invited to participate returned consent/assent forms and participated in the first wave of data collection. Participants completed follow-up surveys once a year for three additional years. The questionnaire was consistent in content and length. For Waves 2 and 3, researchers returned to the schools to distribute questionnaires during class time. Participants were sent questionnaires in the mail if they were no longer in school or if they were absent the day the surveys were administered. Data for Wave 4 was collected through postal mail due to our older cohort having already graduated from school. Adolescents received $25 for participating in Wave 1 of the study, which involved an additional daily diary component that is not reported on in the current paper, $15 for W2 and W3 each, and $20 for W4. Retention rates were 91 % of the original sample for Wave 2, 87 % of the original sample for Wave 3, and 67 % for Wave 4.

Given our interests in examining change over the high school years, our analyses were conducted such that 9th grade represented the intercept and we excluded data from surveys completed after high school. Analyses were thus conducted with four waves of data from the original 9th grade cohort and three waves from the 10th grade cohort. Given our analytical approach, we excluded participants with only one wave of data which resulted in a final analytical sample of 159 adolescents.

Measures

Perceived Discrimination

To measure perceptions of discrimination, adolescents were asked, “How often have you felt racial or ethnicity-based discrimination in the following situations?” in reference to a list of seven items (e.g., being treated unfairly, being disliked). On a five-point scale ranging from 1 = never to 5 = all the time, respondents indicated the frequency of each event. This measure was developed for and has been successfully used with multiple ethnic groups, including Asian Americans (Greene et al. 2006). Internal consistencies ranged from .87 to 92. For the current analyses, responses were recoded to a 0–4 scale.

Model Minority Stereotyping

Modeled after the discrimination measured adapted by Greene et al. (2006) and also used in the current study, Thompson and Kiang (2010) created a measure to assess Asian American adolescents’ perceptions of model minority stereotyping. Participants were asked, “How often do you feel that your ethnicity leads people to automatically assume that you are…” They then responded to a list of nine items, each describing a trait commonly associated with Asian Americans. Some of the traits were positive in nature (e.g., intelligent, ambitious, industrious/hardworking), some tapped into common generalizations (e.g., talented in classical music, good at math/science, family-oriented), and some items were arguably less inherently positive and perhaps viewed as potentially demeaning (e.g., quiet or reserved, courteous/polite, likely to pursue a prestigious career). Items were originally rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = never to 5 = all of the time, and responses were recoded such that the intercept could be set at 0. Internal consistencies ranged from .76 to .84.

Perceived Academic Performance

Adapted from Eccles (1983) and used successfully in prior work with Asian Americans (Fuligni et al. 2005; Kiang et al. 2013), two items were combined to create an index of perceived academic performance. For one item, adolescents were asked, “How good are you at school?” and responded on a scale of 1 = not at all good to 5 = very good. On a scale of 1 = worst to 5 = best, adolescents were also asked, “If you were to rank all the students in your grade from the worst to the best in their classes, where would you put yourself?” Depending on study wave, these two items were correlated .47 to .73, p < .001. Responses were recoded to a 0–4 scale.

School Value

Attitudes towards the utility value of school has been considered a salient academic outcome in prior work and was measured using four items adapted from Eccles (1983). These items have been used successfully in prior research with Asian American adolescents (Fuligni et al. 2005). Students reported on the importance of being in school on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all important, 5 = very important), recoded to 0 to 4. They were also asked how important they believe school is in their everyday life currently, for the future, and after graduating. Internal consistencies ranged from .70 to .80.

Positive Relationships with Others

Used in prior work with Asian American adolescents (Thompson and Kiang 2010), the positive relationships subscale from Ryff’s (1989) psychological well-being measure assessed positive relationships. Nine items are scored from 1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree. Most of the items tap into peer and general social relationships (e.g., “I know I can trust my friends, and they know they can trust me,” “Maintaining close relationships has been difficult and frustrating for me”), and one item taps into both peer and family relationships (e.g., “I enjoy personal and mutual conversations with family members or friends”). Internal consistencies ranged from .76 to .80. Items were recoded to a 0–5 scale.

Self-Esteem

Self-esteem was assessed using the widely-used Rosenberg self-esteem scale (Rosenberg 1986). Ten items were rated on a 5-point scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree, with higher values indicating higher self-esteem. Sample items include, “I feel that I have a number of good qualities,” and, “I take a positive attitude towards myself.” Although some recent work suggests that the negatively-worded items of Rosenberg’s scale might not be appropriate for some immigrant samples (Supple and Plunkett 2011), we used the entire scale including reverse-coded items given that the internal consistencies of all items in the current study ranged from .84 to .87. Prior work with Asian American adolescents has also used the full scale successfully (Huynh and Fuligni 2010; Kiang et al. 2013). Responses were re-coded to a 0–4 scale.

Depressive Symptoms

Also widely used, including among Asian American youth (Huynh and Fuligni 2010; Kiang et al. 2013), the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CESD-10; Andresen et al. 1994) was used to measure symptoms of depression experienced within the previous week. Ten items were rated on a 4-point scale (0 = rarely or none of the time, 3 = most or all of the time). Higher scores indicate higher levels of depressive symptoms. The internal consistencies ranged from .75 to .80.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Before testing our hypotheses, we conducted preliminary analyses to examine whether there were differences in any of our time-varying variables (perceived discrimination, MMS, perceived academic performance, school value, positive relationships with other, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms) according to number of waves of participation. Most youth completed all waves, with those who began in 9th grade completing an average of 3.95 (SD = .22) waves and those who began in 10th grade completing an average of 2.92 (SD = .27) waves. To determine if there were differences in any of the variables as a function of the proportion of possible waves completed, Hierarchical Linear Models (HLM; Bryk and Raudenbush 1992) were estimated using the following equations:

Equation 1 represents scores on the key study variable across the waves of participation, and Eq. 2 shows how the average score was modeled as a function of number of waves of participation. There were no differences in any of the study variables according to the proportion of waves completed.

Normative Changes in Model Minority Stereotyping and Discrimination

The first goal of this study was to examine normative change over time in adolescents’ experiences of the model minority stereotype (MMS) and of discrimination. Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM; Bryk and Raudenbush 1992) was used given the nested structure of the data, with time points nested within participants. Separate models were tested for the two outcomes variables. The specific estimated statistical model was as follows:

As shown in Eq. 3, adolescents’ experiences with the MMS or discrimination in a particular year (i) for a particular individual (j) was modeled as a function of the individual’s average experience with the stereotype/discrimination (b0j) and the year of the study (b1j). Year was coded such that ninth grade = 0, tenth grade = 1, eleventh grade = 2, and twelfth grade = 3. Equations 4 and 5 show how both the average levels of stereotyping/discrimination and the effect of study year were modeled as a function of gender and generational status. Gender was coded as females = 0 and males = 1. Generation was coded as foreign-born or first-generation = 0 and US-born or second-generation = 1. These Level 2 variables were grand-mean centered such that the models can be interpreted as average effects, rather than for a specific group.

As shown in Table 1, adolescents reported increasing experiences of the model minority stereotype over the high school years and decreasing levels of discrimination. No gender or generational differences were found in either average levels of stereotyping experiences or discrimination, or the normative linear change of either over time.

The intercept for the former was 2.69 whereas the intercept for discrimination was 1.21, which suggests that adolescents generally report more experiences with the stereotype than with discrimination. Indeed, descriptive analyses conducted at each year of school found that adolescents’ reported experiences of the model minority stereotype were significantly higher than reported experiences of discrimination. The mean differences between ranged from 1.49 to 2.03 (SD = 1.11–1.17), ts (dfs = 79–154) = 11.64–20.24, ps < .001.

Associations Between Model Minority Stereotyping and Discrimination

Another goal of the study was to explore associations between perceptions of the model minority stereotype and discrimination. First, analyses were conducted in which discrimination was predicted by MMS and time. Gender and generation were included as predictors on the intercept as control variables. The specific estimated statistical model was as follows:

As shown in Eq. 6, discrimination in a particular year (i) for a particular individual (j) was modeled as a function of the individual’s average level of discrimination (b0j), one’s perception of the model minority stereotype that year (b1j) and the year of the study (b2j). MMS was uncentered and year was coded such that ninth grade = 0, tenth grade = 1, eleventh grade = 2, and twelfth grade = 3. Equation 7 shows how average level of discrimination was modeled as a function of gender and generational status. Gender was coded as females = 0 and males = 1. Generation was coded as foreign-born or first-generation = 0 and US-born or second-generation = 1. These Level 2 variables were grand-mean centered such that the models can be interpreted as average effects, rather than for a specific group.

As shown in Table 2, model minority stereotyping was not significantly associated with discrimination, controlling for time. The reverse model was also tested, with stereotyping as the outcome variable and discrimination as the key predictor. Also shown in Table 2, in this model, discrimination was also not a significant predictor of stereotyping, again controlling for time.

Associations Between Model Minority Stereotyping, Discrimination, and Adjustment

The final goal was to explore associations between stereotyping, discrimination, and their interaction with adjustment. We focused on diverse indicators of adjustment including perceptions of academic performance, school value, positive relationships, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms. As before, HLM was used and gender and generation were included as predictors on the intercept. The specific estimated statistical model was as follows:

As shown in Eq. 10, adjustment in a particular year (i) for a particular individual (j) was modeled as a function of the individual’s average level of adjustment (b0j), one’s perception of the model minority stereotype that year (b1j), discrimination that year (b2j), the interaction between MMS and discrimination (b3j), and the year of the study (b4j). MMS and discrimination were centered prior to the creation of the interaction term. Year was coded such that ninth grade = 0, tenth grade = 1, eleventh grade = 2, and twelfth grade = 3. Equation 11 shows how average level of adjustment was modeled as a function of gender and generational status, both of which were coded and centered as before. In these models, Level 2 variances were initially constrained to zero because there were more Level 1 parameters than time points. A two-step process was used to select the most parsimonious models (see Bryk and Raudenbush 1992). First, all Level 2 variance parameters were fixed to equal zero except for that of the baseline. Freed parameters were kept only when a likelihood ratio test indicated a significantly improved model fit (i.e., p < .05) (see Nishina and Juvonen 2005; Kiang et al. 2013). Using this method, variance for MMS was freed for perceived academic performance and positive relationships. No parameters beyond baseline were freed for school value, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms.

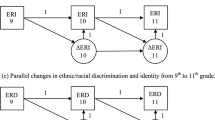

As shown in Table 3, for most of the outcome variables, MMS and discrimination independently predicted adjustment, with MMS promoting and discrimination hindering adjustment. Further, as shown in Fig. 1, MMS was protective of school adjustment in terms of attenuating the negative effect of discrimination on perceptions of academic performance. The same pattern of interaction was found for school value (see Fig. 2).

Discussion

Asian Americans are unique in that they experience their share of negative discrimination, yet the common social perception of their standing as a model minority often runs counter to blatantly unfavorable views. Such public perceptions operate through the lens of academic and character-based assumptions that collectively have a more positive connotation and might not involve inherently negative traits. Despite being a well-known phenomenon, there is a lack of systematic research that fully deconstructs the prevalence and implications of the model minority experience. To address this gap in the literature, the current study aimed to quantify the prevalence of adolescents’ perceptions of the model minority stereotype, examine how it is intertwined with perceptions of negative discrimination and bias, and how both stereotyping and discrimination exert main and interactive effects on adjustment.

No work of which we are aware has simultaneously tracked changes in both the model minority stereotype and negative discrimination. The scarce existing research that has examined discrimination alone among Asian American youth has largely found perceptions to increase over time, perhaps as adolescents become more aware of societal bias and inequities (Wang and Atwal 2014). Although, as expected, the normative pattern of change found here for model minority stereotyping appears to fit prior evidence for incremental increases over time, we did not find similar support for developmental increases in negative discrimination. In fact, contrary to our hypotheses, perceptions of discrimination significantly decreased over time. Although more work needs to be done, one explanation for these divergent results could be that our sample was recruited from emerging immigrant communities in the US. Most of the existing work on discrimination has focused on large metropolitan areas such as Los Angeles or New York City that have a long standing immigrant presence (e.g., Greene et al. 2006; Huynh and Fuligni 2010; Niwa et al. 2014). Cross-sectional research focusing on Latin American youth suggests that the experience of discrimination is qualitatively different in traditional versus emerging immigrant communities (Perreira et al. 2010). Among Asian American adults, Syed and Juan (2012) also found that the effect of discrimination on distress varied depending on social context and the environment’s ethnic density. Comparative work centering on the possible differences or similarities among Asian Americans who reside in traditional and non-traditional settlement areas could be helpful in replicating and clarifying our results. Notably, some work with adolescents and emerging adults residing in a traditional area of migration has found that perceptions of discrimination decrease over the transition to college, perhaps as people mature, gain more exposure to diverse peers, or become more covert in expressing their tendency to discriminate (Huynh and Fuligni 2012). Nuances in linear trajectories of perceived discrimination have been also found depending on the source of discrimination and on the specific ethnicity and social standing of respondents (Greene et al. 2006; Niwa et al. 2014). Given these nuances and the limited longitudinal work that exists, more research that incorporates multi-wave data is needed. In particular, in light of the growth and opportunities that occur post-high school and in the transition to college and/or the work force, perhaps targeting longer developmental periods and individual differences would be useful in further extending our understanding of normative change in perceptions of unfair treatment during adolescence and beyond.

In terms of the normative increase in perceptions of model minority stereotyping, changes in such perceptions could be potentially spurred by processes of ethnic exploration and identity formation, which are developmentally relevant during the adolescent years (Erikson 1968; Thompson et al. 2015). Reports of ethnic stereotyping could rise along with such growing ethnic awareness, and future research could consider how identity might be intricately linked to race-related social interactions and exposure or sensitivity to stereotypes. Yet, in light of these speculations regarding identity formation and exploration, it is notable that discrimination did not also increase over time. Hence, an alternative explanation is that the academic domain could become more salient and challenging to negotiate as high school progresses. Given that much of the model minority stereotype revolves around themes of academic success and achievement (Cocchiara and Quick 2004; Suzuki 2002), perhaps opportunities to be pegged as the highly achieving model student increase over time, which could predict increases in perceptions of the model minority stereotype, but not necessarily predict increases in discrimination. More research should attempt to further deconstruct stereotyping from discrimination experiences, and perhaps uncover more of their qualitative differences and similarities.

Interestingly, perceptions of model minority stereotyping and discrimination were not associated with each other. Contrary to prior work suggesting that model minority assumptions about Asian Americans could serve to instigate unfair treatment from peers in the form of negative discrimination (Niwa et al. 2014; Qin et al. 2008; Rosenbloom and Way 2004), we found little evidence to support our hypothesis that one type of experience would be directly related to the other. Although speculative, it is possible that these two types of experiences are associated, but earlier in adolescence or middle childhood when children are just beginning to work through their interactions with others and decipher their relative social standing. It is also possible that our specific measures were not able to fully address the issue of inter-relatedness, given that they were not originally designed to either complement or distinctly measure each experience apart from the other. Additional research that uses more targeted measures to assess, for instance, experiences of discrimination that are a direct consequence of the model minority image, could provide further insight into how these different interactions might be related. Notably, the direction of effect that was found here, while not statistically significant, does suggest a positive association, with awareness of one being linked to awareness of the other. Descriptively, it is also notable that perceptions of the model minority stereotyping were more prevalent, with average responses falling between “a few times” to “several times”, compared to discrimination, with responses hovering between “once or twice” and “a few times”.

Consistent with the idea that the model minority stereotype and discrimination are predominately independent from each other, they also exerted largely independent effects on adjustment. In line with prior work (Huynh and Fuligni 2010; Niwa et al. 2014; Wang and Atwal 2014), discrimination hindered outcomes and, as hypothesized, was significantly linked to lower valuing of school, lower positive relationships with others, lower self-esteem, and higher depressive symptoms. In contrast, the effects of the model minority stereotype were advantageous with higher perceptions being linked to higher perceived academic performance, school valuing, positive relationships, and self-esteem. Although these results only partially supported our hypotheses that perceptions of the stereotype would be beneficial for academic outcomes but detrimental for psychosocial adjustment, the findings are generally consistent with at least some of the prior literature on the model minority stereotype that points to its potential benefits (Shih et al. 1999; Thompson and Kiang 2010; Whaley and Noel 2013). What is more, the positive effects of model minority stereotyping actually counteracted the negative consequences of discrimination on our two academic outcomes. Youth who reported high levels of discrimination tended to report low perceived academic performance and low valuing of school, but those who also reported frequent experiences with the model minority stereotype were protected from these negative effects. The hypothesized moderating effects of stereotyping on the link between discrimination and academic outcomes were therefore supported; however, contrary to expectations, these experiences did not appear to exacerbate each other in terms of non-academic outcomes.

While we are loathe to imply that any ethnic-based stereotype is a blessing, our data suggest that being portrayed as a model minority could have some advantages, at least when pitted against the effects of more negative discriminatory views. Such findings are consistent with theories of self-development (e.g., symbolic interactionism) (Harter 1999), which would argue that internalization of favorable views such as being intelligent or a hard worker contributes to similarly positive self-evaluations. More generally speaking, it seems worthwhile to uncover ways to capitalize on positive views and minimize negative ones in order to best promote adolescent outcomes, particularly in light of the academic domain. That said, it is also important to consider whether there might be circumstances in which the stereotype could be developmentally harmful. In Yoo et al.’s (2010) conceptualization of the model minority stereotype, which includes dimensions of achievement orientation as well as unrestricted mobility or the belief that Asian Americans face fewer racial barriers than other ethnic groups, agreement with the stereotype of achievement was positive for some outcomes, but internalization of unrestricted mobility was associated with greater distress. Future work should, therefore, continue to examine how the model minority stereotype itself can be multifaceted, as well as how individual differences in internalizing or endorsing the image can potentially confer different outcomes.

It could be also worthwhile for future work to identify differential predictors of model minority stereotyping and discrimination experiences, particularly since they appear to operate distinctly. One idea is to examine the impact of ethnic socialization. For instance, preparation for bias is an ethnic socialization message that seems especially relevant to negative discriminatory interactions (Hughes et al. 2006). Yet, can preparation for bias also educate youth about more diverse stereotypes about their group? Are there other ways to socialize children and youth and teach them about ethnic-based interactions that involve generalized attitudes rather than behavioral bias, some views of which might be perceived as relatively innocuous or even positive?

In light of our overall results, several limitations to the current study should be noted. To add to the caveat mentioned earlier with regards to measurement and the operationalization of our constructs, we should note that our measures did not specify the source of stereotyping or discrimination experiences. Some prior work has found that the impact of discrimination on outcomes can vary based on whether the perpetrators are peers or adults (Greene et al. 2006). Although it is likely that, given that this was a school-based study, adolescents were reporting on experiences that occurred in school, our measures of stereotyping and discrimination did not differentiate these contexts. Hence, more nuanced measurement and analyses could be addressed in future research. More detailed measurement of peer relationships should also be done. Our measure of positive relationships was global in nature, and assessed “friends” and “others” in general. It would be important and meaningful in future work to examine whether different processes and outcomes might be found for same- versus different-ethnic peers. Perhaps perceptions of model minority stereotyping are positive for same-ethnic relationships but not for cross-ethnic relationships in which the possibility of triangulation and resentment might occur.

Another drawback is the limited of generalizability of our sample. Although one strength of our study was its focus on an understudied population in a geographic region in need of more research attention, it is unclear whether our findings are unique to Asian Americans, to Asian Americans in emerging immigrant communities, or both. Future work is needed to replicate our results. Given that we recruited our sample from areas where the overall Asian American population is small, we were also limited to using a panethnic sample and did not have the statistical power to test for any effects across specific Asian subgroups. Such sample characteristics could be another explanation for why some of our results diverged from existing work, which has tended to either focus on similarly panethnic samples or samples that are predominantly Chinese American or East Asian (e.g., Greene et al. 2006; Huynh and Fuligni 2010; Liang et al. 2007). The heterogeneity of Asian Americans is often overlooked and more targeted within-group investigations are necessary (Wong and Halgin 2006). This is particularly important in terms of understanding the model minority stereotype, given that recent reports emphasize that many refugees and immigrants from Southeast and South Asian areas do not readily fit the model minority image (Asian American Federation 2014). A relatively large portion of our sample was indeed Southeast Asian, whereas other notable representations were of East and South Asian ancestry. Such heterogeneity should be considered in light of interpreting our results. Similarly, it would be important for future research to examine whether the knowledge gained here might apply to other ethnic minority and immigrant groups. Although the model minority stereotype itself is unique to Asian Americans, stereotypes for other groups can connote both negative and positive traits.

Conclusion

In reality, all adolescents experience a range of stereotypes and ethnic-based social interactions that can be perceived as promotive or hindering. Our study aimed to uncover some of the varied experiences that Asian American adolescents face and supports the utility of continued explorations in understanding the diverse social interactions that youth must navigate. Our results suggest that perceptions of model minority stereotyping and more negative discrimination form different experiences for Asian American adolescents. Although perceptions of discrimination appear to be relatively stable, model minority stereotyping actually increased over time. Their effects are largely independent with discrimination serving as a detriment and with stereotyping being positively linked to outcomes and even attenuating some of the negative effects of discrimination on academic adjustment. Although, again, we do not condone stereotyping itself, perhaps trying to minimize behavioral bias while capitalizing more generally on the advantages of positive societal views, such as in the form of enhancing public regard, could be beneficial to all youth.

References

Ambady, N., Shih, M., Kim, A., & Pittinsky, T. L. (2001). Stereotype susceptibility in children: Effects of identity activation on quantitative performance. Psychological Science, 12, 385–390. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00371.

Ambady, N., Shih, M., & Pittinsky, T. L. (1999). Stereotype susceptibility: Identity salience and shifts in quantitative performance. Psychological Science, 10, 80–83. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00111.

Andresen, E. M., Malmgren, J. A., Carter, W. B., & Patrick, D. L. (1994). Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 10(2), 77–84. doi:10.1037/t10141-000.

Asian American Federation. (2014). The state of Asian American children. New York, NY: Asian American Federation.

Benner, A. D., & Graham, S. (2011). Latino adolescents’ experiences of discrimination across the first 2 years of high school: Correlates and influences on educational outcomes. Child Development, 82, 508–519. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01524.x.

Bryk, A. S., & Raudenbush, S. W. (1992). Hierarchical linear models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Chang, D. F., & Demyan, A. (2007). Teachers’ stereotypes of Asian, Black, and White students. School Psychology Quarterly, 22(2), 91–114. doi:10.1037/1045-3830.22.2.91.

Cheryan, S., & Bodenhausen, G. V. (2000). When positive stereotypes threaten intellectual performance: The psychological hazards of model minority status. Psychological Science, 11, 399–402. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00277.

Cocchiara, F. K., & Quick, J. C. (2004). The negative effects of positive stereotypes: Ethnicity-related stressors and implications on organizational health. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(6), 781–785. doi:10.1002/job.263.

Eccles, J. S. (1983). Expectancies, values, and academic behaviors. In J. T. Spence (Ed.), Achievement and achievement motivation (pp. 75–146). San Francisco: Freeman.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton.

Fishbein, H. D. (1996). Peer prejudice and discrimination: Evolutionary, cultural, and developmental dynamics. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Fuligni, A., Kiang, L., Witkow, M., & Baldelomar, O. (2008). Stability and change in ethnic labeling among adolescents from Asian and Latin American immigrant families. Child Development, 79, 944–956. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01169.x.

Fuligni, A. J., Witkow, M., & Garcia, C. (2005). Ethnic identity and the academic adjustment of adolescents from Mexican, Chinese, and European backgrounds. Developmental Psychology, 41(5), 799–811. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.41.5.799.

Garcia Coll, C., Crnic, K., Lamberty, G., Wasik, B. H., Jenkins, R., Garcia, H. V., & McAdoo, H. P. (1996). An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development, 67(5), 1891–1914. doi:10.2307/1131600.

Greene, M. L., Way, N., & Pahl, K. (2006). Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimination among Black, Latino, and Asian American adolescents: Patterns and psychological correlates. Developmental Psychology, 42, 218–238. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.218.

Harter, S. (1999). The construction of the self: A developmental perspective. New York: Guilford Press.

Ho, C., & Jackson, J. W. (2001). Attitudes toward Asian Americans: Theory and measurement. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31(8), 1553–1581. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2001.tb02742.x.

Hughes, D., Rodriguez, J., Smith, E. P., Johnson, D. J., Stevenson, H. C., & Spicer, P. (2006). Parents’ ethnic–racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology, 42(5), 747–770. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747.

Hurh, W. M., & Kim, K. C. (1989). The ‘success’ image of Asian Americans: Its validity, and its practical and theoretical implications. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 12(4), 512–538. doi:10.1080/01419870.1989.9993650.

Huynh, V. W., & Fuligni, A. J. (2010). Discrimination hurts: The academic, psychological, and physical well-being of adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 20, 916–941. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00670.x.

Huynh, V. W., & Fuligni, A. J. (2012). Perceived ethnic stigma across the transition to college. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41, 817–830. doi:10.1007/s10964-011-9731-x.

Inhelder, B., & Piaget, J. (1958). The growth of logical thinking from childhood to adolescence. New York: Basic Books.

Kiang, L., Witkow, M. R., & Champagne, M. C. (2013). Normative changes in ethnic and American identities and links with adjustment among Asian American adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 49(9), 1713–1722.

Kim, J. (2001). Asian American identity development theory. In C. L. Wijeyesinghe & B. W. Jackson III (Eds.), New perspectives on racial identity development (pp. 67–90). New York: New York University Press.

Lee, S. J. (1996). Unraveling the “model minority” stereotype: Listening to Asian American Youth. New York: Teachers College Press.

Liang, B., Grossman, J. M., & Deguchi, M. (2007). Chinese American middle school youths’ experiences of discrimination and stereotyping. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 4, 187–205.

Maas, C. J., & Hox, J. J. (2005). Sufficient sample sizes for multilevel modeling. Methodology, 1, 86–92.

Ngo, B., & Lee, S. J. (2007). Complicating the image of model minority success: A review of Southeast Asian American education. Review of Educational Research, 77(4), 415–453. doi:10.3102/0034654307309918.

Nishina, A., & Juvonen, J. (2005). Daily reports of witnessing and experiencing peer harassment in middle school. Child Development, 76(2), 435–450. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00855.x.

Niwa, E. Y., Way, N., & Hughes, D. L. (2014). Trajectories of ethnic–racial discrimination among ethnically diverse early adolescents: Associations with psychological and social adjustment. Child Development, 85, 2339–2354. doi:10.1111/cdev.12310.

Niwa, E. Y., Way, N., Qin, D. B., & Okazaki, S. (2011). Hostile hallways: Asian American adolescents’ experiences of peer discrimination in school. In F. Leong, L. Juang, & D. B. Qin (Eds.), Asian American and Pacific Islander Children and Mental Health (pp. 193–217). Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO.

Oyserman, D., & Sakamoto, I. (1997). Being Asian American: Identity, cultural constructs, and stereotype perception. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 33(4), 435–453. doi:10.1177/0021886397334002.

Perreira, K. M., Fuligni, A., & Potochnick, S. (2010). Fitting in: The roles of social acceptance and discrimination in shaping the academic motivations of Latino youth in the US Southeast. Journal of Social Issues, 66(1), 131–153. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.2009.01637.x.

Peterson, W. (1966). Success story: Japanese-American style. New York Times Magazine, 9, 20–43.

Phinney, J. S., & Chavira, V. (1995). Parental ethnic socialization and adolescent coping with problems related to ethnicity. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 5, 31–53.

Qin, D. B., Way, N., & Rana, M. (2008). The “model minority” and their discontent: Examining peer discrimination and harassment of Chinese American immigrant youth. In H. Yoshikawa & N. Way (Eds.), Beyond the family: Contexts of immigrant children’s development. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 212, 27–42.

Rosenberg, M. (1986). Conceiving the self. Malabar, FL: Krieger.

Rosenbloom, S. R., & Way, N. (2004). Experiences of discrimination among African American, Asian Americans, and Latino Adolescents in an urban high school. Youth and Society, 35, 420–451. doi:10.1177/0044118x03261479.

Rosenthal, R., & Jacobson, L. (1968). Pygmalion in the classroom. New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 1069–1081. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069.

Shih, M., Ambady, N., Richeson, J. A., Fujita, K., & Gray, H. M. (2002). Stereotype performance boosts: The impact of self-relevance and the manner of stereotype activation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(3), 638–647. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.83.3.638.

Shih, M., Pittinsky, T. L., & Ambady, N. (1999). Stereotype susceptibility: Identity salience and Shifts in quantitative performance. Psychological Science, 10(1), 80–83. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00111.

Snijders, T. A. B. (2005). Power and sample size in multilevel linear models. In B. S. Everitt & D. C. Howell (Eds.), Encyclopedia of statistics in behavioral science (Vol. 3, pp. 1570–1573). New York: Wiley.

Supple, A. J., & Plunkett, S. W. (2011). Dimensionality and validity of the Rosenberg self-esteem scale for use with Latino adolescents. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 33, 39–53.

Suzuki, B. H. (2002). Revisiting the model minority stereotype: Implications for student affairs practice and higher education. New Directions for Student Services, 97, 21–32. doi:10.1002/ss.36.

Syed, M., & Juan, M. J. D. (2012). Discrimination and psychological distress: Examining the moderating role of social context in a nationally representative sample of Asian American adults. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 3, 104–120. doi:10.1037/a0025275.

Thompson, T. L., & Kiang, L. (2010). The model minority stereotype: Adolescent experiences and links with adjustment. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 1(2), 119–128. doi:10.1037/a0019966.

Thompson, T. L., Kiang, L., & Witkow, M. R. (2015). “You’re Asian; you’re supposed to be smart”: Adolescents’ experiences with the model minority stereotype and longitudinal links with identity (under review).

Wang, C., & Atwal, K. (2014). School climate, discrimination, and depressive symptoms. Contemporary School Psychology, 18, 1–13. doi:10.1007/s40688-014-0040-8.

Wang, J., Siy, J. O., & Cheryan, S. (2011). Racial discrimination and mental health among Asian American youth. In F. Leong, L. Juang, & D. B. Qin (Eds.), Asian American and Pacific Islander Children and Mental Health (pp. 219–242). Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO.

Whaley, A. L., & Noel, L. T. (2013). Academic achievement and behavioral health among Asian American and African American adolescents: Testing the model minority and inferior minority assumptions. Social Psychology of Education, 16(1), 23–43. doi:10.1007/s11218-012-9206-2.

Wong, F., & Halgin, R. (2006). The “model minority”: Bane or blessing for Asian Americans? Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 34, 38–49. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1912.2006.tb00025.x.

Wong, Y. J., Owen, J., Tran, K. K., Collins, D. L., & Higgins, C. E. (2012). Asian American male college students’ perceptions of people’s stereotypes about Asian American men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 13(1), 75–88. doi:10.1037/a0022800.

Wu, F. (2002). Yellow: race in America beyond black and white. New York: Basic Books.

Yoo, H. C., Burrola, K. S., & Steger, M. F. (2010). A preliminary report on a new measure: Internalization of the Model Minority Myth (IM-4) and its psychological correlates among Asian American college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57(1), 114–127. doi:10.1037/a0017871.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the schools and individual adolescents who participated in the study. Funding for the study, in part, was made possible by a Wake Forest University SBE grant awarded to LK.

Author Contributions

L.K. designed and coordinated the larger study from which this manuscript is based. T.T. helped to collect data and conceive of the manuscript’s initial research questions. M.W. performed the statistical analyses. All authors participated in the interpretation of the data, drafted specific sections of the manuscript, read, and approved the final product.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kiang, L., Witkow, M.R. & Thompson, T.L. Model Minority Stereotyping, Perceived Discrimination, and Adjustment Among Adolescents from Asian American Backgrounds. J Youth Adolescence 45, 1366–1379 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-015-0336-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-015-0336-7