Abstract

Adolescents exposed to domestic violence are at high risk for dating abuse. This randomized controlled trial evaluated a dating abuse prevention program designed specifically for this risk group. Moms and Teens for Safe Dates consisted of six mailed booklets of dating abuse prevention information and interactive activities. Mothers who had been victims of domestic violence but no longer lived with the abuser delivered the program to their adolescents who had been exposed to the abuse. Mother and adolescent pairs (N = 409) were recruited through community advertising; the adolescents ranged from 12 to 16 years old and 64 % were female. Mothers and adolescents completed baseline and 6-month follow-up telephone interviews. Booklet completion in the treatment group ranged from 80 % for the first to 62 % for the last booklet. The analyses first tested whether program effects on dating abuse varied by four a priori identified moderators (mother’s psychological health, the amount of adolescent exposure to domestic violence, and adolescent sex and race/ethnicity). Main effects of the program were examined when there were no differential program effects. Program effects on psychological and physical victimization and psychological and cyber perpetration were moderated by the amount of adolescent exposure to domestic violence; there were significant favorable program effects for adolescents with higher, but not lower levels of exposure to domestic violence. There were no moderated or main effects on sexual violence victimization and perpetration or cyber victimization. The findings suggest that a dating abuse prevention program designed for adolescents exposed to domestic violence can have important positive effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Dating abuse has negative developmental, physical and mental health consequences for adolescents. Approximately 30 % of adolescents in abusive relationships report receiving injuries from their dating partner (Callahan et al. 2003; O’Leary et al. 2008). Further, longitudinal studies indicate that adolescent victims of dating abuse are at increased risk of becoming depressed and anxious, initiating cigarette, alcohol, and illicit substance use, developing suicide ideations, becoming involved in antisocial behaviors, and becoming a victim of domestic violence as an adult (Exner-Cortens et al. 2013; Foshee et al. 2013). Thus, preventing dating abuse is important for healthy adolescent development.

Adolescents who have been exposed to domestic violence are at particularly high risk for dating abuse and its negative sequelae (Foshee et al. 1999; O’Donnell et al. 2006). Finkelhor et al. (2013) estimate that 28 % of adolescents have witnessed domestic violence, which translates to about 4.8 million adolescents in the United States. Yet despite the large number of adolescents who have been exposed to domestic violence and their high risk for dating abuse, no studies have evaluated a dating abuse prevention program for this population. Dating abuse prevention programs designed for the general population of adolescents may not be appropriate for this high risk population because exposure to domestic violence may influence adolescents’ cognitions, beliefs, practices, and skill-sets, and these need to be considered in prevention programming. Also, developing a program specific to a particular risk population allows tailoring of program materials to make them more meaningful to participants (Thorton et al. 2000). This paper presents the results from the first randomized controlled trial to test the efficacy of a dating abuse prevention program, Moms and Teens for Safe Dates (MTSD), designed specifically for adolescents exposed to domestic violence.

The MTSD Program

The MTSD program consists of six booklets of dating abuse prevention information and interactive activities that mothers who are former victims of domestic violence but who no longer live with the abuser do with their adolescents who were exposed to the violence. The booklets are delivered by mothers who are former rather than current victims of domestic violence to allow for safer delivery of the program to adolescents. The program is designed for mother rather than father delivery because, although there are exceptions, mothers are typically the primary caregivers of their children. Also, results from randomized trials of programs designed to prevent other types of problem behaviors (e.g., conduct disorder, aggression) among youth exposed to domestic violence indicate that programs that target both the mother and child (Graham-Bermann et al. 2007; Jouriles et al. 2001) are more efficacious than those that target only the mother (McFarlane et al. 2005) or only the child (Wagar and Rodway 1995).

The overall goals of the MTSD program are to motivate and facilitate mothers’ engagement with their adolescents in carrying out the dating abuse prevention activities described in the booklets in order to enhance protective factors and decrease risk factors for dating abuse and, ultimately decrease dating abuse perpetration and victimization. Specifically, the program is intended to prevent dating abuse by (1) enhancing factors that motivate and facilitate mothers’ engagement in dating abuse prevention activities (2) increasing mother monitoring of the adolescent, family closeness and cohesion, and adolescent conflict management skills (protective factors); and (3) reducing adolescent acceptance of dating abuse and gender stereotyping (risk factors). Each of these factors have been found to predict or protect against dating abuse among adolescents exposed to domestic violence (Foshee et al. 1999; Lichter and McCloskey 2004) and therefore guided program content. The booklets are mailed to the home to be completed at times convenient for the family. They include a variety of interactive activities such as role plays, puzzles, games, scenario analyses, and guided discussions designed to change each of the targeted factors. Based on characterizations of adolescent abusive relationships (Mulford and Giordano 2008), the activities depict both boys and girls as perpetrators and victims of dating abuse and provide examples of both mutually and unilaterally abusive relationships. Details on the conceptual model and program activities for the MTSD program can be found in Foshee et al. (2014).

The Development of the MTSD Program

We developed the MTSD program by culturally adapting an evidence-based dating abuse prevention program designed for the general population of adolescents to adolescents exposed to domestic violence (Foshee et al. 2014). Developing a program through an adaptation process is less time- and resource-intensive than developing a program de novo and can accelerate development (Wingood and DiClemente 2008). The goal of a cultural adaptation is to modify the original program to accommodate the unique cultural beliefs, risk factors and circumstances of the target group while maintaining the core elements or internal logic of the original program (Falicov 2009). In this case, the adaptation focused on incorporating the unique circumstances of exposure to domestic violence into the program.

The program we chose for adaptation was Families for Safe Dates, which consists of six booklets of dating abuse prevention information and interactive activities that parents do with their adolescents. We chose Families for Safe Dates for several reasons. The self-administered booklet structure of Families for Safe Dates has been found to be an appropriate mode of program delivery for high-risk families; Haggerty et al. (2006, 2007), for example, found that in a high risk sample, family participation in and the effectiveness of a family-based program for preventing adolescent problem behaviors were higher when self-administered through booklets than when delivered in a group. Also, the content of Families for Safe Dates was guided by risk and protective factors that, as noted earlier, are relevant for adolescents exposed to domestic violence. Further, a national randomized controlled trial found that Families for Safe Dates was efficacious in changing many of these risk and protective factors and preventing dating abuse (Foshee et al. 2012). Also, families in the Families for Safe Dates trial found the booklet format of the program convenient, yielding high program participation (Foshee et al. 2012).

The process we used to adapt the Families for Safe Dates program to create the MTSD program is described in detail in Foshee et al. (2014). Briefly, we reviewed the conceptual underpinnings of Families for Safe Dates and made adjustments based on empirical research and knowledge of the target population, while maintaining the core components and logic of the original program (Lau 2006). We then revised the booklet content to reflect the adjustments made to the conceptual model. Next, mothers who were former victims of domestic violence and their adolescents who had been exposed to the violence completed booklets in their homes and provided feedback on each booklet in 12 focus groups and 107 in-depth interviews. We revised the booklet content based on this feedback and administered the revised booklets to additional eligible families. Finally, we revised the booklets one more time based on feedback from those families.

A detailed description of the content adaptations made to Families for Safe Dates in creating the MTSD program is in Foshee et al. (2014). But as some examples: (1) we added gender stereotyping to the conceptual model of the MTSD program because of evidence that traditional gender stereotyping is reinforced by witnessing domestic violence (Graham-Bermann and Brescoll 2000) and is associated with dating abuse (Durán et al. 2010; Vandiver and Dupalo 2013); thus we developed activities to decrease adolescent acceptance of traditional gender stereotypes; (2) because mothers in the adaptation study were adamant about ensuring that their adolescents recognized psychological abuse and saw it as a precursor to physical violence, we gave psychological abuse more prominence in the scenarios and activities to increase the relevance of the program for these mothers; (3) we increased the number of activities designed to teach adolescents how to manage their anger and prevent anger from leading to dating abuse because of the high level of anger observed in the adolescents in the adaptation study; (4) we eliminated Families for Safe Dates activities designed to promote parent and adolescent communication that were contentious for this population and replaced them with activities that promoted communication but that were less contentious, and; (5) because many of the mothers were overly strict and dogmatic when it came to their adolescent’s dating, with some saying that they would not allow their adolescent to date at all until very late ages, we added content to the Getting Started booklet (which was for mothers only) on the potential negative consequences of being overly strict and inflexible about dating.

The Randomized Controlled Trial of the MTSD Program

The MTSD program was evaluated with a randomized controlled trial funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A primary aim of the trial was to determine whether program effects on dating abuse perpetration and victimization varied by four a priori specified moderator variables: the mother’s psychological health, the amount of exposure the adolescent had to domestic violence, and the sex and race/ethnicity of the adolescent. A program that has beneficial effects for some may have no effects or even worse, iatrogenic effects for others. Thus, knowing whether program effects vary by sub-groups is important for making decisions about program implementation and dissemination.

The MTSD program depends on delivery by mothers who have been victims of domestic violence, which has been shown to have long-lasting detrimental effects on psychological health (Black 2011). Mothers with poor psychological health may be less able to effectively deliver the program than those with good psychological health. Thus, it was important to determine whether poor psychological health interfered with mothers’ program delivery and, consequently, dampened program effectiveness.

Although the MTSD program was designed for adolescents who have been exposed to domestic violence, there is heterogeneity among this group in terms of the duration and severity of the exposure. Numerous studies have indicated that the detrimental effects of exposure to domestic violence on children and adolescents, including effects on abusive dating behaviors (Jouriles et al. 2012; Temple et al. 2013), increase with increasing severity of the exposure (Johnson and Lieberman 2007). Adolescents with greater as compared to lower exposure to domestic violence may thus have more entrenched cognitions that support the use of violence, and as a result, they may be more difficult to “move” with an intervention. At the same time, however, Flay et al. (2004) have suggested that it is more difficult to reduce violent behaviors among those with lower base rates of violence, and thus the MTSD program might have stronger effects on those with greater exposure to domestic violence because of their higher base rates of dating violence. Thus, it was important to determine whether the effects of the MTSD program varied depending on the amount of exposure the adolescent had had to domestic violence.

There is strong evidence that both boys and girls perpetrate and are victims of dating abuse (Foshee and Reyes 2011), and therefore dating abuse prevention efforts are needed for both boys and girls. Thus, it was important to determine whether program effects were present for both boys and girls. Sex of the adolescent did not moderate the effects of several dating abuse prevention programs for the general population, including the Shifting Boundaries program (Taylor et al. 2013), the Safe Dates program (Foshee et al. 2005), and the Families for Safe Dates program from which the MTSD program was adapted (Foshee et al. 2012), and it did not moderate the effects of a dating abuse prevention program designed for adolescents who had been maltreated (Wolfe et al. 2003). However, the sex of the adolescent did moderate the effects of the 4th R dating abuse prevention program (Wolf et al. 2009), with effects on the perpetration of dating abuse for boys, though not girls. Also, the effects of several youth violence prevention programs have been found to vary by the sex of the adolescent (Farrell et al. 2001; Flay et al. 2004).

Base rates of dating abuse (Foshee et al. 2009) and risk and protective factors for dating abuse (Foshee et al. 2010) have been found to vary by race/ethnicity, and racial/ethnic differences have been noted in exposure to key risk factors for violence (McNulty and Bellair 2003). Additionally, racial/ethnic differences have been noted in the detrimental effects of exposure to domestic violence (Spilsbury et al. 2007). These differences could produce variations in reactivity to dating abuse prevention programs. Even so, race/ethnicity has been examined as a moderator only in the trial evaluating Safe Dates (Foshee et al. 2005), which found that race/ethnicity did not moderate program effects. However, racial/ethnic differences have been found in the effects of programs for preventing other types of youth violence (Hawkins et al. 1991).

The Current Study

The current study is a randomized controlled trial of the MTSD program that was conducted with adolescents exposed to domestic violence. We examined the effects of the program on four types of dating abuse perpetration and victimization: psychological, physical, sexual and technology assisted dating abuse, referred to here as cyber dating abuse. We hypothesized that the adolescents randomized to receive the MTSD program would report less of each of these types of dating abuse 6 months after program exposure than those randomly allocated to the control group. Because of the importance for implementation and dissemination of determining if program effects vary by sub-groups, we determined if the effects of the MTSD program on the dating abuse outcomes varied by the mother’s psychological health, the amount of exposure the adolescent had to domestic violence, and the sex and race/ethnicity of the adolescent. As described above, there are reasons to believe that the effects of the MTSD program could vary by sub-groups based on these attributes of the mother and adolescent. If the MTSD program is found to be efficacious, the booklet format makes it relatively inexpensive to deliver by agencies that come in contact with adolescents who have been exposed to domestic violence such as domestic violence agencies and coalitions, social services, and courts.

Methods

Study Design

Mothers who had been in an abusive relationship but were currently living apart from the abusive partner were recruited into a randomized controlled trial from North Carolina and across the nation, along with their 12–15 year-old adolescent who had been exposed to the domestic violence. Recruited mothers and adolescents completed a 25-min baseline telephone interview, then were randomly allocated to the treatment or control condition. Families in the treatment group were mailed a program booklet every 2 weeks. Families in the control group were not sent any program materials. Nine months after baseline (6 months post-intervention completion), the mothers and the adolescents were interviewed again by telephone. The mothers provided consent for their own and the adolescent’s participation. The adolescents provided verbal assent for their participation. Procedures were approved by the University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board.

Recruitment

Our primary recruitment strategy was through coalitions that were part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Domestic Violence Prevention Enhancement and Leadership Alliances (DELTA) program. DELTA is a mechanism used by CDC for promoting the primary prevention of intimate partner violence in communities. We worked most closely with the North Carolina DELTA coalition [North Carolina Coalition against Domestic Violence (NCCADV)] because of their proximity to the investigators, but recruitment also occurred through many of the other 14-state coalitions. NCCADV provides domestic-violence-related training and support services to local domestic violence agencies and professionals throughout NC. NCCADV staff gave brief presentations about the study during trainings for professionals who work with victims of domestic violence, and gave the participants study flyers to pass on to potentially eligible women at their agencies. Staff at other coalitions also gave study flyers to potentially eligible women. To supplement these efforts, study information and flyers were also sent directly to departments of social services and to domestic violence and sexual assault agencies in North Carolina and a number of other states, and study recruitment posters were advertised on the mass transit system in Atlanta and on commuter rails in Philadelphia. All recruitment materials included a toll free number for women to call if they were interested in participating in the study.

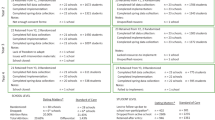

Sample Description

Using these recruitment methods, a total of 409 families (mothers and adolescents) were recruited into the study. A slight majority of the families were from North Carolina (51 %; n = 209), followed by Georgia (24 %; n = 100) and Pennsylvania (12 %; n = 50), with the remainder from Delaware, Montana, Virginia, Rhode Island, Oregon, Ohio, California, Minnesota, Alabama, Texas, North Dakota, Vermont, New York and Wisconsin. Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the sample.

Approximately 66 % of the adolescents had been exposed to domestic violence perpetrated by the biological father and 52.6 % had been exposed to violence against the mother by more than one perpetrator. The average length of adolescent exposure to domestic violence was 5 years and 4 months (SD = 4 years), with a range from 1 month to 16 years. Mothers’ mean score on the Women’s Experiences with Battering (WEB) Scale (Smith et al. 1995), which measures psychological vulnerability that results from experiencing domestic violence, was 20.70 (range of 6–24; SD = 4.19) when completed in reference to the partner the adolescent was exposed to most. The WEB has good construct validity, accurately discriminates battered from non-battered women, and has strong internal consistency reliability (Smith et al. 1999). A WEB score of 15 or above is considered “battered” and indicates high levels of psychological vulnerability (Coker et al. 2002). Over half (58.2 %) of the mothers had filed for a Domestic Violence Protection Order (DVPO) against the partner that the adolescent was exposed to most, and 51.0 % of the women had received a DVPO.

Of the 409 recruited families, 305 mothers (75 %) and 295 adolescents (72 %) completed the 6-month follow-up interview. In assessing program effects, the analytic sample was limited to the 295 families in which an adolescent completed the follow-up interview.

Attrition

There were no treatment group differences in the amount of attrition between baseline and the follow-up (Chi Square = .40; df = 1; p = .53). Also, treatment condition did not interact with the baseline demographic, moderator, or lifetime dating abuse variables in predicting study dropout. Thus, there was no evidence of differential predictors of attrition by treatment condition. Additionally, there were no main effects of any of these variables on study drop-out except for baseline cyber dating abuse victimization: those who had been victims of cyber dating abuse were more likely to drop out by follow-up than those who had not been victimized by cyber dating abuse (b = .05; p = .02).

Program Exposure

The first booklet (Getting Started) was for mothers only, and the other five booklets were activity booklets for the mother and the adolescent to do together. Each of the five activity booklets included a card that asked a series of questions that could be answered only if the family had done that booklet’s activities. The card also included a space for filling in a “secret code” that was revealed throughout the booklet as families completed activities. After completing a booklet, families answered the questions, filled in the secret code, and then mailed the completed card to the study office. The adolescents were then sent a $15 Visa gift card for completion of the booklet. Based on the number of cards received, 80, 74, 75, 69 and 62 % of the families completed activity booklets one through five, respectively. None of the proposed moderators was associated with the number of booklets completed.

Measures

Dating Abuse Outcomes

The program effects were assessed on eight dating abuse behaviors: the perpetration of and victimization from psychological, cyber, physical, and sexual dating abuse. Prior to answering the questions about dating abuse, the adolescents were asked if they had ever been on a date, defined as informal activities like going out in a group and then pairing up with someone they were interested in and meeting someone they were interested in at the mall, a park, or at a basketball game, or more formal activities like going out to eat or to a movie together. If the adolescent responded “yes,” then they completed the dating abuse questions. At baseline the questions were in reference to “ever,” whereas at the follow-up, the questions were in reference to “past 3 months.” Response options to all of the dating abuse questions ranged from “never” to “more than 4 times.” Table 2 presents the lifetime prevalence of experiencing or perpetrating at least one act of each type of dating abuse and the prevalence of each act that comprises each type of abuse.

Psychological Dating Abuse

The perpetration of and the victimization from psychological dating abuse were assessed with items from the Safe Dates Psychological Dating Abuse Scales (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2006; Foshee 1996). The Safe Dates Dating Abuse Scales (for assessing psychological and physical dating abuse) have high internal consistency (α = .94) and are among the most widely used scales for assessing dating violence among adolescents (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2006). The scales have been found to correlate with other constructs as expected and produce prevalence estimates comparable to those produced with other dating abuse scales (Foshee et al. 2001). To assess perpetration, the adolescent was asked how many times he/she had ever (1) insulted a date in front of others, (2) not let a date do things with other people, (3) threatened to hurt a date, (4) hurt a date’s feelings on purpose, and (5) said mean things to a date. Parallel questions were asked to assess victimization by asking adolescents how many times these things had been done to them. Responses were summed to create the perpetration of psychological dating abuse and the victimization from psychological dating abuse composite variables.

Cyber Dating Abuse

The perpetration of and victimization from cyber dating abuse were measured using a modified version of the Tech Abuse in Teen Relationships scale for measuring cyber dating abuse (Picard 2007). The psychometric properties of this scale have not been reported. To assess perpetration, adolescents were asked how many times they had done the following things to a person they were dating using a cell phone, email, IM, text messaging, Web chat, a blog or a networking site like MySpace or Facebook: (1) spread rumors about someone they were dating, (2) called the person bad names, put him/her down, or said really mean things to the person, (3) showed private or embarrassing pictures/videos of the person to others, and/or (4) repeatedly checked up on the person to see where he or she was. Victimization from cyber dating abuse was assessed by asking adolescents how many times these things had been done to them. Responses were summed to create the perpetration of cyber dating abuse and the victimization from cyber dating abuse composite variables.

Physical Dating Abuse

The perpetration of and victimization from physical dating abuse were assessed with items from the Safe Dates Physical Dating Abuse Scale Scales (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2006; Foshee 1996). To assess perpetration, the adolescent was asked how many times he/she had ever: (1) slapped or scratched a date, (2) physically twisted a date’s arm or bent back his or her fingers, (3) pushed, grabbed, shoved or kicked a date, (4) hit a date with a fist or something hard, and/or (5) assaulted a date with a knife or gun. Adolescents were instructed not to count acts perpetrated in self-defense. Victimization from physical dating abuse was assessed by asking adolescents how many times these things had been done to them that were not done in self-defense. Responses were summed to create the perpetration of physical dating abuse and the victimization from physical dating abuse composite variables.

Sexual Dating Abuse

The perpetration of sexual dating abuse was assessed with 5 items that asked how many times the adolescent had ever (1) kissed a date when he/she did not want to be kissed, (2) showed a date pictures of naked people that the date did not want to see, (3) showed a date his or her private parts when the date did not want to see them, (4) put his or her hand on one of the date’s private parts when the date did not want that, and/or (5) forced someone to have sex or to do something else sexual that the person did not want to do. Victimization from sexual dating abuse was assessed by asking adolescents how many times these things had been done to them. Responses were summed to create the perpetration of sexual dating abuse and the victimization from sexual dating abuse composite variables. These scales were developed specifically for use in this study.

Moderator Variables

The Mother’s Psychological Health

This moderator was assessed with 10 items from the Perceived Life Stress Scale (PSS-10; Cohen et al. 1983) and 4 items from the CES-D Depression Scale (Radloff 1977). The PSS-10 has strong psychometric properties; it has been associated with several biological indicators of stress and stress related illnesses and its scores are high in groups known to be experiencing stress (Cohen and Janicki-Deverts 2012). The CES-D is one of the most widely accepted and used measures of depression, and has been shown to have high reliability and validity across a wide variety of samples (e.g., Knight et al. 1997; Radloff 1991). For both scales, the mothers were asked “How often in the past 4 weeks have you…” Sample items from the PSS-10 were “felt that you could not cope with all the things that you had to do,” “felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life,” and “felt difficulties were piling up so high that you could not overcome them.” Sample items from the CES-D depression scale were “had trouble keeping your mind on what you were doing” and “felt depressed.” Response options range from 1 for “never” to 4 for “very often.” The 14 items were summed and averaged, with higher values indicating worse psychological health (α = .89; mean = 2.45; SD = .5699; range 1.077–4.000).

The Amount of Adolescent Exposure to Domestic Violence

To measure the amount of adolescent exposure to domestic violence, the mothers were first asked to think about the abusive partner that the adolescent was around for the longest period of time. The mothers indicated how many times this partner used the following abusive acts against them, “used a knife or gun on you”, “beat you up”, “hit you with a fist or with something else hard”, “pushed, grabbed, or shoved you”, “slapped or scratched you,” “threatened you with physical harm”, “insulted you”, and “did something to humiliate you,” and then were asked the percentage of these times the adolescent had heard or witnessed the abusive act. The number of times the adolescent had witnessed or heard each of these acts was then calculated and these were summed. This score was coded into quartiles, with the highest score (3) indicating the greatest amount of exposure to domestic violence and the lowest score (0) indicating the least amount of exposure.

The Sex of the Adolescent

This moderator was coded such that 0 = female and 1 = male.

The Race/Ethnicity of the Adolescent

The race/ethnicity of the adolescent was coded using two indicator variables, one for black race and one for other race, so that the referent group was white.

Control Variables

Analyses controlled for baseline age of the adolescent (in years) and the mother’s education, the baseline value of the specific dating abuse outcome, and dating status at follow-up. Mother’s education was coded with two dummy variables: one an indicator of exactly a high school education or the equivalent and the other an indicator of more than a high school education, with the referent being not graduating from high school. Baseline dating abuse was controlled using the measures described above, with the time referent being “ever.” Dating status was based on the question at the follow-up about whether the adolescent had ever dated.

Analytical Strategy for Testing Treatment Effects

An intent-to-treat approach was used; that is, analyses were based on the treatment condition families were assigned to, not on the amount of treatment received (Wright and Sim 2003). Prior to testing for program effects, analyses were conducted to determine if there were baseline differences between the treatment and control groups on key study variables. There were no significant differences at baseline between the groups on any of the demographic, moderating, or dating abuse behavior outcomes.

Analyses first examined whether program effects on the dating abuse outcomes varied by the four moderator variables: mother’s psychological health, the amount of adolescent exposure to domestic violence, and the sex and race/ethnicity of the adolescent. When there was no evidence of differential program effects, the main effects of the program on the dating abuse outcomes were examined. Moderation was first tested, then main effects because main effects can be incorrect if there are differential effects by sub-groups of the program on outcomes (Aguinis et al. 2005; Kleinbaum et al. 1982; Warner 2013).

The effects of the MTSD program (0 = control and treatment = 1) on each of the dating abuse outcomes at the follow-up and moderators of program effects were tested with linear regression. The follow-up dating abuse outcomes (referencing behaviors over the prior 3 months) were regressed on treatment condition, the moderator variables, the control variables, and the interaction between treatment condition and each of the moderators. We employed backwards elimination, dropping non-significant interactions from the model to produce a reduced model for each dating abuse outcome (Kleinbaum et al. 1982). When significant interactions were identified, post hoc analyses were conducted to determine program efficacy at various levels of the moderator variable. In models where none of the interactions were significant, all of the interactions were dropped and the main effect of the program on that dating abuse outcome was interpreted.

Once the final model for each outcome was established, effect sizes were examined in two ways. The interaction effect size was examined using the f 2 statistic which is the increment in the R-Squared from the main effects model to the model including the significant interaction(s), divided by one minus the R-Squared of the full [including the interaction(s) term] model (Aiken and West 1991). When statistically significant program effects were found within-in sub-groups through the post hoc analyses, Cohen’s d was used as an indicator of program effect size in the sub-group (Cohen 1988). Cohen’s d was calculated by dividing the treatment effect by the pooled standard deviation. The pooled standard deviation was computed by pooling the standard deviation of the predicted mean for the treatment group and the predicted mean for the control group at varying levels of the moderators, setting other covariates equal to their sample means (Cohen 2013).

We implemented multiple imputation using SAS PROC MI, imputing moderators and control variables to avoid listwise deletion due to missing values. The regression analyses were performed using PROC GLM in SAS 9.3. with PROC MIANALYZE used to aggregate the results from the multiple imputations (SAS Institute Inc. 2012). It is important to note, however, that the study conclusions regarding which associations were and were not statistically significant were the same with and without MI.

Results

The Effects of the MTSD Program on Victimization from Dating Abuse

Table 3 presents the effects of the MTSD program on the four types of victimization from dating abuse. The effects of the program on victimization from psychological and physical dating abuse victimization were moderated by the amount of exposure the adolescent had had to domestic violence. The f 2 associated with the interaction between treatment condition and exposure to domestic violence in the victimization of psychological dating abuse model was 0.016. The results from the post hoc analyses of the interaction indicated that the MTSD program had significant effects on victimization from psychological dating abuse, in the expected direction, for adolescents who had high exposure to domestic violence (defined as 1 SD above the mean) (b = −0.8311, p = .0158), but not for adolescents with average (defined as the mean) (b = −0.2727, p = .1891) or low exposure to domestic violence (defined as 1 SD below the mean) (b = 0.2857, p = .3881). The Cohen’s d for those who had high exposure to domestic violence was 0.17.

The f 2 associated with the interaction between treatment condition and exposure to domestic violence in the victimization of physical dating abuse model was 0.021. The nature of this interaction was similar to the nature of the interaction when predicting victimization from psychological dating abuse; The MTSD program had significant effects, in the expected direction, for adolescents who had high exposure to domestic violence (b = −0.4066, p = .0512), but not for adolescents with average (b = −0.0145, p = .9085) or low exposure to domestic violence (b = 0.3776, p = .0608). The Cohen’s d for those who had high exposure to domestic violence was 0.14. Although not statistically significant, there was a trend toward program effects in the opposite direction for adolescents with the least exposure to domestic violence. We investigated the nature of this interaction further by examining the association between the amount of exposure to domestic violence and victimization from physical dating abuse by treatment condition. We found that the amount of exposure to domestic violence was predictive of victimization from physical dating abuse in the control group (b = .17, p = .0296) but not in the treatment group (b = −.0896, p = .23). The nature of this interaction is presented in the top panel of Fig. 1. The finding suggests that exposure to the program buffered the adverse effects of exposure to domestic violence on this dating abuse outcome. There were no program effects on victimization from sexual or cyber dating abuse.

The Effects of the MTSD Program on the Perpetration of Dating Abuse

Table 4 presents program effects on the perpetration of the four types of dating abuse. The effects on the perpetration of psychological and cyber dating abuse were moderated by the amount of exposure the adolescent had had to domestic violence. The f 2 associated with the interaction between treatment condition and exposure to domestic violence in the perpetration of psychological dating abuse model was 0.041. The MTSD program had significant effects on the perpetration of psychological dating abuse, in the expected direction, for adolescents who had high exposure to domestic violence (b = −0.9394, p = .0006), but not for adolescents who had average (b = −0.2248, p = .1719) or low exposure to domestic violence (b = 0.4899, p = .0614). The Cohen’s d for this outcome was 0.24 for adolescents who had high exposure. Again, although not statistically significant, there was a trend toward program effects in the opposite direction for adolescents with the least exposure to domestic violence. As we did earlier, we investigated the nature of this interaction by examining the association between the amount of exposure to domestic violence and the perpetration of psychological dating abuse by treatment condition. Again, we found that being exposed to the program buffered the negative effects of exposure to domestic violence on dating abuse: the amount of exposure to domestic violence was predictive of the perpetration of psychological dating abuse in the control group (b = .38, p = .0002) but not in the treatment group (b = −.0934, p = .3425). The nature of this interaction is presented in the bottom panel of Fig. 1.

The f 2 associated with the interaction between treatment condition and exposure to domestic violence in the perpetration of cyber dating abuse model was 0.015. The MTSD program had significant program effects on the perpetration of cyber dating abuse, in the expected direction, for adolescents who had high exposure to domestic violence (b = −0.3879, p = .0336), but not for adolescents who had average (b = −0.0945, p = .3912) or low exposure to domestic violence (b = 0.1989, p = .2575). The Cohen’s d associated with program effects for adolescents with high exposure to domestic violence was 0.15. There were no program effects on the perpetration of physical or sexual dating abuse.

Discussion

Dating abuse can interfere with the healthy development of adolescents. In addition to its detrimental physical and psychological consequences (Exner-Cortens et al. 2013; Foshee et al. 2013), dating abuse can interfere with important developmental tasks of adolescence such as the formation of identity, autonomy and individuation, and the development of loyalty, trust, and secure attachment, self-regulatory capabilities, self-perceived competence in romantic relationships, and skills in communicating and interacting with others (Collins 2003; Giordano 2003), each of which can negatively impact future relationships. The prevention of dating abuse is warranted. A group that is at particularly high risk for involvement in dating abuse and its negative consequences is adolescents who have been exposed to domestic violence (Foshee et al. 1999; O’Donnell et al. 2006), yet there have been no evaluations of dating abuse prevention programs designed specifically for this high risk group.

This study reports the findings from the first randomized controlled trial of a dating abuse prevention program designed specifically for adolescents exposed to domestic violence. Program effects on four types of dating abuse perpetration and victimization (psychological, physical, sexual, and cyber) were examined. Because of the importance for dissemination of determining if program effects vary in sub-groups, four a priori specified moderators of program effects on those outcomes were examined: the mother’s psychological health, the amount of exposure the adolescent had to domestic violence, and the sex and race/ethnicity of the adolescent.

Significant effects of the MTSD program were found, but the effects varied by the dating abuse outcome considered and the amount of exposure the adolescent had had to domestic violence. There were significant program effects on victimization from psychological and physical dating abuse, and perpetration of psychological and cyber dating abuse for adolescents who had had higher but not lower exposure to domestic violence. There were no program effects on sexual violence victimization or perpetration, and none of the program effects were moderated by the sex and race/ethnicity of the adolescent or the mother’s psychological health.

The program appeared to be more effective for adolescents at the greatest risk as defined by greater exposure to domestic violence. Flay et al. (2004) suggested that the effects of programs to prevent adolescent risk behaviors may be stronger for higher than lower risk adolescents because their behavior is easier to “move” with interventions given their higher base rates of the risk behavior. However, we found no support for this explanation for the stronger program effects for adolescents with greater exposure to domestic violence: exposure to domestic violence was not associated with baseline values of any of the types of dating abuse victimization and perpetration. The amount of exposure the adolescent had had to domestic violence was also not associated with the number of booklets completed. Thus, the stronger program effects for adolescents with higher exposure to domestic violence are not explained by their completion of a greater number of booklets. However, the mothers with the greatest domestic violence victimization may have been more effective deliverers of the program. Because of their keen awareness of the detrimental effects of partner violence, perhaps these women took program delivery more seriously, strictly following the booklet instructions and more emphatically reinforcing the messages. It may also be that these mothers benefitted more from having a structure for conversations with their adolescent about a sensitive topic that affected them so directly and personally. It is also possible that adolescents with the greatest exposure took the program more seriously than the adolescents with lower exposure. Because our study did not include collection of any information on how the program was delivered or perceived by the mothers and received by the adolescents, we cannot confirm these speculations.

Although significant program effects were present for those with higher exposure to domestic violence, the strength of the program effects is likely small; however, making that determination is not straightforward. The effect sizes (f 2) for the significant interactions in this study ranged from .015 to .041. Cohen (1988) suggested that f 2 effect sizes of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 are considered small, medium, and large, respectively. However, in noting that the average f 2 found in a 30 year review of moderation studies was .009 (Aguinis et al. 2005), Kenny (2013) suggested that more realistic guidelines for f 2 may be 0.005, 0.01, and 0.025 for small, medium and large, respectively. The Cohen’s d associated with the significant effects of the MTSD program ranged from 0.14 to 0.24 which are small effect sizes based on Cohen’s (1988) designation of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 as small, medium and large, respectively. However, numerous studies have criticized the practice of designating effect sizes as small, medium or large because those designations can be meaningless without contextualizing the findings in prior research (Aguinis et al. 2005; Baguley 2004; Glass et al. 1981; Robinson et al. 2003); for example a Cohen’s d of .2 may have substantial substantive significance in some research areas, and a Cohen’s d of .6 may not be of importance in other areas (Glass et al. 1981; Robinson et al. 2003). Unfortunately no prior randomized trial of a dating abuse prevention program reported f 2 or Cohen’s d for program effects on dating abuse behaviors. However, the Cohen’s d associated with the significant effects of a dating abuse prevention program for male athletes on intentions to intervene in dating abuse situations and positive bystander reactions were .12–.28 respectively (Miller et al. 2012) and the Cohen’s d for the effects of Families for Safe Dates on parent’s knowledge and attitudes about dating abuse ranged from .25 to .44 and on adolescent attitudes about the acceptance of dating abuse was .37 (Foshee et al. 2012). Our reporting of f 2 and Cohen’s d will allow for making comparisons of program effects on dating abuse behaviors in future research.

There were no program effects on the sexual dating abuse outcomes. Evaluations of dating abuse prevention programs often do not examine program effects on sexual dating abuse because of low prevalence rates in these outcomes. To ensure that low prevalence rates for these outcomes did not preclude our ability to examine program effects on them, we created sexual dating abuse scales that included items tapping into less severe forms of sexual dating violence that many adolescents may experience (e.g., having a kiss forced on them). However, although we found some variation in the lifetime prevalence of the perpetration of sexual dating abuse, with 6.60 % of the adolescents reporting perpetration, the prevalence was probably still too small to adequately test for program effects. In contrast, the lifetime prevalence of victimization from sexual dating abuse was found to be 20.7 %, and thus there was probably enough variation in that outcome to assess program effects, yet no program effects were found. It is possible that the lack of program effects on these outcomes could have been due to measurement limitations; the scales were new and no psychometric tests had been conducted with them. Most of the program effects were found for the psychological and physical dating abuse outcomes, which were measured with established scales that have been used in numerous dating abuse prevention studies for years. It is also possible, of course, that the MTSD program is not effective in preventing sexual dating abuse.

There were no significant iatrogenic effects of the MTSD program. However, there was a trend suggesting that among adolescents with the least exposure to domestic violence, effects on the victimization from physical dating abuse and the perpetration of psychological dating abuse were in the opposite direction than that anticipated. This can be seen at values of zero on exposure to domestic violence in the figure; at the lowest level of exposure to domestic violence, the mean scores on these two dating abuse outcomes were higher, though not significantly higher, in the treatment group than in the control group. However, when we investigated these interactions further, we found that the effects of exposure to domestic violence on the two dating abuse outcomes were significant and positive for the control group, but not for the treatment group. Thus, the program appeared to be buffering the negative effects of exposure to domestic violence on these dating abuse outcomes, which is a favorable program effect.

The primary limitation of the study relates to the external validity or generalizability of the findings. The sample was a convenience sample, and the characteristics of the sample suggest that it was not representative of all adolescents in the US exposed to domestic violence. Approximately 60 % of the mothers in the sample were unemployed and 64 % were single; also 84 % of the families received public assistance, suggesting that the sample was primarily low SES. While adolescents at all socioeconomic levels are exposed to domestic violence, the study findings may not generalize to adolescents at higher SES levels who have been exposed to domestic violence. However, there are few other sampling options besides convenience sampling for identifying adolescents exposed to domestic violence because there are generally not any lists of adolescents exposed to domestic violence from which to draw a probability sample.

Another factor that may limit the generalizability of study findings is that attrition was fairly high. However, there were negligible baseline differences between those who completed the follow-up and those who dropped out of the study, suggesting that the analytic sample represented the sample of families recruited into the trial. A further limitation was reliance on self-reports of dating abuse; however there are no better options for measuring adolescent dating abuse since very few incidents are witnessed by others or appear in the law enforcement system and adolescents typically do not tell anyone about the abuse (Foshee 1996). An additional measurement limitation is that collection of self-reports via telephone interviews could have resulted in underestimates of dating abuse victimization and perpetration because social desirability bias has been found to be greater in modes of data collection that do than do not involve the presence of an interviewer (Tourangeau and Yan 2007).

Another limitation is that the measure of adolescent exposure to domestic violence was based on the mother’s identification of the abusive partner that the adolescent was around for the longest period of time, introducing the potential for measurement error since the abusive partner the adolescent was around the longest may not have been the most abusive partner the adolescent was around. Given that approximately 53 % of the mothers had more than one abusive partner after the child was born, it is possible that some adolescents could have been exposed to more severe domestic violence than was captured in the exposure to domestic violence variable. Additionally, we did not assess whether the mother victims were also perpetrators of abuse. Bi-directional violence between partners is not uncommon (Archer 2000). It is possible that program effects could vary by whether the parent delivering the program is a victim only or both a victim and perpetrator of abuse, but we could not assess this possibility. Finally, in this study, mother, but not father, victims of domestic violence delivered the intervention and therefore we could not assess the possibility that the sex of the parent influences program effectiveness. There is clear evidence that a substantial number of men are victims of domestic violence (Archer 2000), and their adolescents also need dating abuse prevention programs. In the MTSD program, only the Getting Started booklet, which was only for the mothers, referenced the mother’s abuse. Thus, with some slight editing to this booklet the program could also be delivered by father victims of domestic violence.

The study has many strengths. Although a dating abuse prevention program designed for adolescents who have been victims of child abuse has been evaluated (Wolfe et al. 2003), this is the first evaluation of a dating abuse prevention program designed specifically for adolescents exposed to domestic violence. The program was adapted from an evidence-based program that was guided by a theoretically and empirically based conceptual model compatible with the etiology of dating abuse among adolescents exposed to domestic violence (Foshee et al. 2012, 2014). An extensive process was followed to culturally adapt Families for Safe Dates to this high risk group in developing the MTSD program (Foshee et al. 2014). Participation in the program was relatively high, especially given the high risk sample. The study used a randomized design, eliminating many potential threats to the internal validity of the findings. Although threats to validity posed by differential attrition and/or differential predictors of attrition by treatment condition were not controlled for by design, it is unlikely that our favorable effects were due to those factors because the attrition was similar for the treatment and control groups and there were negligible differential predictors of attrition that could have produced spurious program effects. Also, contamination between the treatment and control groups was unlikely because the families in the trial were spread out over a large geographic area; thus the integrity of the design was maintained.

Additionally, the moderation analyses met many criteria that are deemed important in judging the quality of sub-group analyses (Kenny 2013; Sun et al. 2012; Warner 2013). Sub-group differences were tested through significance testing of interactions; the moderators were selected a priori; less than 5 moderators were included in the analyses; the moderator variables were measured prior to randomization to treatment condition; the independent variable (treatment condition) was manipulated through randomization; the moderator variables and the independent variable were not significantly associated; the differential program effects were consistent across multiple outcomes and the nature of the moderation was consistent across multiple outcomes, with the program being more effective for those with higher than lower exposure to domestic violence in all cases; moderation was tested when controlling for potentially confounding variables; and there are potential explanations for the sub-group differences found. Despite meeting these criteria, however, it is still possible that the significant interactions were due to chance alone and it will be important to determine if these interactions can be replicated in future evaluations of the MTSD program (Warner 2013).

Conclusion

In this first randomized controlled trial of a dating abuse prevention program for adolescents exposed to domestic violence, we found favorable effects of the MTSD program in preventing the perpetration of and victimization from multiple types of dating abuse among adolescents with higher but not lower exposure to domestic violence. These findings are encouraging and suggest that the MTSD program may be a viable program to use for dating abuse prevention among this high risk group of adolescents. However, future evaluations of the MTSD program are needed to determine whether the program effects, and particularly the differential program effects, can be replicated.

References

Aguinis, H., Beaty, J. C., Boik, R. J., & Pierce, C. A. (2005). Effect size and power in assessing moderating effects of categorical variables using multiple regression: A 30-year review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 94–107.

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Archer, J. (2000). Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 126(5), 651–680.

Baguley, T. (2004). Understanding statistical power in the context of applied research. Applied Ergonomics, 35, 73–80.

Black, M. C. (2011). Intimate partner violence and adverse health consequences: Implications for clinicians. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 5, 428–439.

Callahan, M. R., Tolman, R. M., & Saunders, D. G. (2003). Adolescent dating violence victimization and psychological well-being. Journal of Adolescent Research, 18(6), 664–681.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2006). Measuring intimate partner violence victimization and perpetration: A compendium of assessment tools. http://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/11402/.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Chicago: Routledge Academic.

Cohen, S., & Janicki-Deverts, D. (2012). Who’s stressed? Distributions of psychological stress in the United States in probability samples from 1983, 2006, and 2009. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 42(6), 1320–1334.

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 385–396.

Coker, A. L., Bethea, L., Smith, P. H., Fadden, M. K., & Brandt, H. M. (2002). Missed opportunities: Intimate partner violence in family practice settings. Preventive Medicine, 34, 445–454.

Collins, W. (2003). More than myth: The developmental significance of romantic relationships during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 13(1), 1–24.

Durán, M., Moya, M., Megías, J. L., & Viki, G. T. (2010). Social perception of rape victims in dating and married relationships: The role of perpetrator’s benevolent sexism. Sex Roles, 62(7–8), 505–519.

Exner-Cortens, D., Eckenrode, J., & Rothman, E. (2013). Longitudinal associations between teen dating violence victimization and adverse health outcomes. Pediatrics, 71, 71–78.

Falicov, C. J. (2009). Commentary: On the wisdom and challenges of culturally attuned treatments for Latinos. Family Process, 48(2), 292–309.

Farrell, A. D., Meyer, A. L., & White, K. S. (2001). Evaluation of Responding in Peaceful and Positive Ways (RIPP): A school-based prevention program for reducing violence among urban adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 30, 451–463.

Finkelhor, D., Turner, H. A., Shattuck, A., & Hamby, S. L. (2013). Violence, crime, and abuse exposure in a national sample of children and youth: An update. JAMA Pediatrics, 167(7), 614–621.

Flay, B. R., Graumlich, S., Segawa, E., Burns, J. L., & Holliday, M. Y. (2004). Effects of 2 prevention programs on high-risk behaviors among African American youth. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine, 158, 377–384.

Foshee, V. (1996). Gender differences in adolescent dating abuse prevalence, types, and injuries. Health Education Research, 11(3), 275–286.

Foshee, V. A., Bauman, K. E., Ennett, S. T., Suchindran, C., Benefield, T., & Linder, G. F. (2005). Assessing the effects of the dating violence prevention program “Safe Dates” using random coefficient regression modeling. Prevention Science, 6, 245–258.

Foshee, V. A., Bauman, K. E., & Linder, G. F. (1999). Family violence and the perpetration of adolescent dating violence: Examining social learning and social control processes. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61(2), 331–342.

Foshee, V. A., Dixon, K. S., Ennett, S. T., Moracco, K. E., Bowling, J. M., Chang, L., & Moss, J. L. (2014). The process of adapting a universal dating abuse prevention program to adolescents exposed to domestic violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence,. doi:10.1177/0886260514552278.

Foshee, V., Linder, F., MacDougall, J., & Bangdiwala, S. (2001). Gender differences in the longitudinal predictors of adolescent dating violence. Preventive Medicine, 32, 128–141.

Foshee, V. A., & Reyes, H. L. M. (2011). Dating abuse: Prevalence, consequences, and predictors. In R. J. R. Levesque (Ed.), Encyclopedia of adolescence. New York: Springer.

Foshee, V. A., Reyes, H. L. M., & Ennett, S. T. (2010). Examination of sex and race differences in longitudinal predictors of the initiation of adolescent dating violence perpetration. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment, and Trauma, 19(5), 492–516.

Foshee, V. A., Reyes, H. L. M., Ennett, S. T., Cance, J. D., Bauman, K. E., & Bowling, J. M. (2012). Assessing the effects of Families for Safe Dates, a family-based teen dating abuse prevention program. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 51(4), 349–356.

Foshee, V. A., Reyes, H. L. M., Gottfredson, N. C., Chang, L. L., & Ennett, S. T. (2013). A longitudinal examination of psychological, behavioral, academic, and relationship consequences of dating abuse victimization among a primarily rural sample of adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53, 723–729. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.06.01.

Foshee, V. A., Reyes, M. L., & Wyckoff, S. (2009). Approaches to preventing psychological, physical, and sexual partner abuse. In D. O’Leary & E. Woodin (Eds.), Psychological and physical aggression in couples: Causes and interventions (pp. 165–189). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Giordano, P. (2003). Relationships in adolescence. Annual Review of Psychology, 29, 257–281.

Glass, G. V., McGaw, B., & Smith, M. L. (1981). Meta-analysis in social research. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Graham-Bermann, S. A., & Brescoll, V. (2000). Gender, power, and violence: Assessing the family stereotypes of the children of batterers. Journal of Family Psychology, 14(4), 600–661.

Graham-Bermann, S. A., Lynch, S., Banyard, V., & DeVoe, E. R. (2007). Community-based intervention for children exposed to intimate partner violence: An efficacy trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75, 199–209.

Haggerty, K. P., MacKenzie, E. P., Skinner, M. L., Harachi, T. W., & Catalano, R. F. (2006). Participation in “Parents Who Care”: Predicting program initiation and exposure in two different program formats. Journal of Primary Prevention, 27, 47–65.

Haggerty, K. P., Skinner, M. L., MacKenzie, E. P., & Catalano, R. F. (2007). A randomized trial of Parents Who Care: Effects on key outcomes at 24-month follow-up. Prevention Science, 8, 249–260.

Hawkins, J. D., Von Cleve, E., & Catalano, R. F., Jr. (1991). Reducing early childhood aggression: Results of a primary prevention program. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 30, 208–217.

Johnson, V. K., & Lieberman, A. F. (2007). Variations in behavior problems of preschoolers exposed to domestic violence: The role of mothers’ attunement to children’s emotional experiences. Journal of Family Violence, 22(5), 297–308.

Jouriles, E. N., McDonald, R., Spiller, L., Norwood, W. D., Swank, P. R., Stephens, N., et al. (2001). Reducing conduct problems among children of battered women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69, 774–785.

Jouriles, E. N., Mueller, V., Rosenfield, D., McDonald, R., & Dodson, M. C. (2012). Teens’ experiences of hush parenting and exposure to severe intimate partner violence: Adding Insult to Injury in predicting teen dating violence. Psychology of Violence, 2(2), 125–138.

Kenny, D. (2013). Moderation. http://davidakenny.net/cm/moderation.htm.

Kleinbaum, D. G., Kupper, L. L., & Morgenstern, H. (1982). Epidemiologic research. London: Lifetime Learning Publications.

Knight, R. G., Williams, S., McGee, R., & Olaman, S. (1997). Psychometric properties of the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) in a sample of women in middle life. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35(4), 373–380.

Lau, A. S. (2006). Making the case for selective and directed cultural adaptations of evidence-based treatments: Examples from parent training. Clinical Psychology-Science and Practice, 13(4), 295–310. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2850.2006.00042.x.

Lichter, E. L., & McCloskey, L. A. (2004). The effects of childhood exposure to marital violence on adolescent gender-role beliefs and dating violence. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 28(4), 344–357.

McFarlane, J. M., Groff, J. Y., O’Brien, J. A., & Watson, K. (2005). Behaviors of children following a randomized controlled treatment program for their abused mothers. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing, 28, 195–211.

McNulty, T. L., & Bellair, P. E. (2003). Explaining racial and ethnic differences in serious adolescent violent behavior. Criminology, 41, 709–748.

Miller, E., Tancredi, D. J., McCauley, H. L., Decker, M. R., Virata, M. C. D., Anderson, H. A., et al. (2012). “Coaching boys into men”: A cluster-randomized controlled trial of a dating violence prevention program. Journal of Adolescent Health, 51(5), 431–438. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.01.018.

Mulford, C., & Giordano, P. C. (2008). Teen dating violence: A closer look at adolescent romantic relationships. NIJ Journal, 261, 34–40.

O’Donnell, L., Stueve, A., Myint-U, A., Duran, R., Agronick, G., & Wilson-Simmons, R. (2006). Middle school aggression and subsequent intimate partner physical violence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 25, 693–703.

O’Leary, K. D., Slep, A. M. S., Avery-Leaf, S., & Cascardi, M. (2008). Gender differences in dating aggression among multiethnic high school students. Journal of Adolescent Health, 42(5), 473–479.

Picard, P. (2007). Tech Abuse in Teen Relationships study: A report prepared for Liz Claiborne Inc. Northbrook, IL: Teenage Research Unlimited (TRU).

Radloff, L. (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychosocial Measurement, 1, 385–401.

Radloff, L. S. (1991). The use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in adolescents and young adults. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 20(2), 149–166.

Robinson, D. H., Whittaker, T., Williams, N., & Beretvas, S. N. (2003). It’s not effect sizes so much as comments about their magnitude that mislead readers. Journal of Experimental Education, 72, 51–64.

SAS Institute Inc. (2012). SAS Software, Version 9.3. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.

Smith, P. H., Earp, J. A., & DeVellis, R. (1995). Development and validation of the Women’s Experiences with Battering (WEB) Scale. Women’s Health, 1, 273–288.

Smith, P. H., Smith, J. B., & Earp, J. A. (1999). Beyond the measurement trap: A reconstructed conceptualization and measurement of woman battering. Psychology Women Quarterly, 23, 177–193.

Spilsbury, J., Belliston, L., Drotar, D., Drinkard, A., Kretschmar, J., Creeden, R., & Friedman, S. (2007). Clinically significant trauma symptoms and behavioral problems in a community based sample of children exposed to domestic violence. Journal of Family Violence, 22(6), 487–499.

Sun, X., Briel, M., Busse, J. W., You, J. J., Akl, E. A., Mejza, F., et al. (2012). Credibility of claims of subgroup effects in randomized controlled trials: Systematic review. British Medical Journal, 334, 1–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.e1553.

Taylor, B. G., Stein, N. D., Mumford, E. A., et al. (2013). Shifting Boundaries: An experimental evaluation of a dating violence prevention program in middle schools. Prevention Science, 14, 64–76.

Temple, J. R., Shorey, R. C., Tortolero, S. R., Wolfe, D. A., & Stuart, G. L. (2013). Importance of gender and attitudes about violence in the relationship between exposure to interparental violence and the perpetration of teen dating violence. Child Abuse and Neglect, 37(5), 343–352.

Thorton, T. N., Craft, C. A., Dahlberg, L. L., Lynch, B. S., & Baer, K. (2000). Best practices of youth violence prevention: A sourcebook for community action. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

Tourangeau, R., & Yan, T. (2007). Sensitive questions in surveys. Psychological Bulletin, 133(5), 859–883.

Vandiver, D. M., & Dupalo, J. R. (2013). Factors that affect college students’ perceptions of rape: What is the role of gender and other situational factors? International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 57(5), 592–612.

Wagar, J. M., & Rodway, M. R. (1995). An evaluation of a group treatment approach for children who have witnessed wife abuse. Journal of Family Violence, 10, 295–306.

Warner, R. M. (2013). Applied statistics: From bivariate through multivariate techniques (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc.

Wingood, G. M., & DiClemente, R. J. (2008). The ADAPT-ITT model: A novel method of adapting evidence-based HIV interventions. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 47, S40–S46. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181605df1.

Wolf, D. A., Crooks, C., Jaffe, P., et al. (2009). A school-based program to prevent adolescent dating violence: A cluster randomized trial. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine, 163(8), 692–699.

Wolfe, D., Wekerle, C., Scott, K., Straatman, A., Grasley, C., & Reitzel-Jaffe, D. (2003). Dating violence prevention with at-risk youth: A controlled evaluation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 279–291.

Wright, C. C., & Sim, J. (2003). Intention-to-treat approach to data from randomized controlled trials: A sensitivity analysis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 56, 833–842.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Justice [NIJ 2008-WG-BX-1003; PI Vangie A. Foshee] which was administered through the Injury Prevention Research Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC-CH) and by a grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC R01CE001867-01; PI Vangie A. Foshee] which was administered through the Department of Health Behavior at UNC-CH. The study was reviewed and approved by the Public Health-Nursing Institutional Review Board for the Protection of Human Subjects at UNC-CH.

Author contributions

VF conceived of the study, co-led the collection of the data, directed statistical analyses, and drafted the manuscript. TB performed the statistical analyses and participated in writing sections of the manuscript related to measurement and statistical analysis. KSD co-led the collection of the data, managed the study, and wrote content related to study recruitment and program participation. LYC and VS conducted analyses to create measures, performed targeted literature searches, and contributed to the substantive content of the paper. STE, KEM, and JMB contributed to the conceptualization and direction of the randomized trial and contributed to the conceptualization, analytic strategy, interpretation of findings and the writing of the manuscript. Additionally, JMB contributed to the overall analytical approach. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Foshee, V.A., Benefield, T., Dixon, K.S. et al. The Effects of Moms and Teens for Safe Dates: A Dating Abuse Prevention Program for Adolescents Exposed to Domestic Violence. J Youth Adolescence 44, 995–1010 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-015-0272-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-015-0272-6