Abstract

Despite ample evidence for the benefits of parental autonomy support and the harms of parental psychological control to Chinese adolescents’ well-being, little is known about what foreshadows these parenting behaviors among Chinese parents. The current research addressed this gap in the literature. It tested the hypothesis that parents’ endorsement of self-development socialization goals (i.e., regarding a positive sense of self in terms of holding optimistic attitudes toward oneself, feeling autonomous in one’s actions, and establishing one’s independence from others, as important for adolescents to develop) and adolescents’ school performance may interact to predict parental autonomy support and psychological control in urban China. Three hundred and forty-one Chinese seventh graders (mean age = 13.30 years, 58 % female) and their parents (186 mothers and 155 fathers) participated. Parents reported on their own and their spouses’ endorsement of self-development socialization goals; adolescents reported on parental autonomy support and psychological control; and adolescents’ grades were obtained from school records. Significant interactions were found between parents’ socialization goals and adolescents’ grades in predicting parenting behaviors. When adolescents were doing well at school, the stronger parents’ endorsement of self-development socialization goals, the greater their autonomy support and the lesser their psychological control; when adolescents were doing poorly at school, regardless of parents’ socialization goals, their autonomy support was relatively low and their psychological control was relatively high. These findings highlight a tension between parental concerns over adolescents’ self-development and academic success, which needs to be resolved to promote autonomy support and prevent psychological control among urban Chinese parents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Decades of research has evidenced the crucial roles of parents’ autonomy support and psychological control in adolescents’ functioning, when adolescents go through the developmental period during which establishing a positive sense of self as an autonomous and independent individual is a salient task (for reviews, see Laursen and Collins 2009; Smetana et al. 2006; Steinberg 1990, 2001). Presumably because it nurtures adolescents’ sense of self, parents’ autonomy support (e.g., allowing adolescents to make choices on their own and encouraging adolescents to express their ideas and opinions freely) is conducive to adolescents’ functioning in various arenas ranging from emotional, academic, behavioral, to social adjustment (e.g., Brenning et al. 2011; Seiffge-Krenke and Pakalniskiene 2011; Soenens and Vansteenkiste 2005). In contrast, presumably because it hurts adolescents’ sense of self, parents’ psychological control (e.g., inducing guilt in adolescents or withdrawing love from adolescents to make them comply with parental wishes) is detrimental to adolescents’ functioning, particularly in the arenas of emotional and social adjustment (e.g., Arim and Shapka 2008; Doyle and Markiewicz 2005; Foster et al. 2008; Loukas et al. 2005; Miller et al. 2011).

Notably, the benefits of parental autonomy support and the harms of parental psychological control have been well documented in diverse cultures (see Barber et al. 2005; Grolnick 2003), including in Chinese societies (e.g., Barber et al. 2005; Lekes et al. 2010; Shek 2007; Vansteenkiste et al. 2005; Wang et al. 2007), where parents of adolescents tend to be less autonomy supportive but more psychologically controlling than their Western counterparts (e.g., Barber et al. 2005; Lekes et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2007). Given the impact of these two parenting dimensions on adolescent development, it is critical to understand their antecedents to inform endeavors at promoting autonomy support and preventing psychological control among parents, and eventually to foster adolescents’ well-being.

Developmental and cross-cultural psychologists have speculated about self-development socialization goals foreshadowing parental autonomy support and psychological control (for a review, see Bugental and Grusec 2006). When parents regard a positive sense of self (e.g., holding optimistic attitudes toward oneself, feeling autonomous in one’s actions, and establishing one’s independence from others) as important for their offspring to develop, they are likely to engage in autonomy-supportive parenting behaviors but refrain from psychologically controlling parenting behaviors. It is further observed that self-development socialization goals tend to be less prioritized in traditionally collectivist cultures such as Chinese societies than in prototypically individualistic cultures such as many Western societies, which may explain Chinese (vs. Western) parents’ dampened autonomy support and heightened psychological control. Intriguingly, recent research has evidenced contemporary Chinese parents’ notable endorsement of self-development socialization goals (see Tamis-LeMonda et al. 2008), underscoring a possible tension between individualistic socialization goals and other cultural precepts about parenting in traditionally collectivist Chinese societies (Grusec and Rudy 2001).

A culturally prescribed central responsibility of Chinese parents is to ensure their offspring’s academic success (see Chao and Tseng 2002; Wu 1996), which may render parents susceptible to parenting behaviors lacking in autonomy support but awash with control in the face of their offspring’s unsatisfactory school performance (see Grolnick 2003; Pomerantz et al. 2005). As the issue of self development gains salience during adolescence, the issue of academic success also becomes pressing, especially in Chinese societies where getting admitted into a good university depends on doing well throughout the secondary-school years and determines one’s career prospects. Thus, how parents balance their self-development socialization goals and their concern over their offspring’s school performance is vital in shaping their parenting behaviors. This research hence investigated the interplay between parents’ self-development socialization goals and adolescents’ school performance in predicting Chinese parents’ autonomy support and psychological control.

Self-Development Socialization Goals and Parental Autonomy Support and Psychological Control

Parents’ socialization goals long have been theorized to be antecedents of parenting behaviors (for reviews, see Bugental and Johnston 2000; Darling and Steinberg 1993; Goodnow 1988). In particular, autonomy-supportive parenting behaviors are believed to ensue from parents’ prioritizing self-development socialization goals, such that parents endeavor to cultivate in their offspring a positive sense of self, which entails their offspring developing into individuals who are affirmative of themselves as well as able to act out of their own will and function effectively by themselves (Chao 2000; Grolnick 2003; see also Bugental and Grusec 2006). Moreover, when parents endorse self-development socialization goals, they are likely to keep off psychologically controlling parenting behaviors, which tend to disrespect and violate their offspring’s sense of self (Barber and Harmon 2002; Barber et al. in press; see also Bugental and Grusec 2006). Despite the aforementioned theoretical speculations relating self-development socialization goals to parental autonomy support and psychological control, there is surprisingly little empirical work exactly testing such links. We located only three studies in the literature that examined self-development socialization goals in connection with aspects of parenting more or less related to autonomy support and psychological control.

In a study based upon university students’ reports on their parents’ socialization goals and parenting styles, Li et al. (2010) found among both Chinese in China and European Americans in the US that self-development socialization goals were related positively to authoritative parenting, which involves autonomy support (Gray and Steinberg 1999), while unrelated to authoritarian parenting, which involves psychological control (Rudy et al. 2008). In a study among Chinese-American and European-American ninth graders and their parents in the US, Padmawidjaja and Chao (2010) found that parent-reported self-development socialization goals were related positively to parent-reported contingent autonomy (e.g., “watches how offspring behaves before giving her/him more freedom”) among Chinese Americans, while negatively related to adolescent-reported parental restricting autonomy (e.g., “gives offspring as much freedom as s/he wants” reverse-keyed) and parent-reported expecting obedience (e.g., “tells offspring to follow parental wishes”) among European Americans. Lastly, in a study based upon the reports by immigrant Chinese and European-American mothers of elementary-school children in the US, Chao (2000) found a positive association between self-development socialization goals and managerial parental involvement in school (e.g., “I check my child’s homework when asked”). Taken together, the aforementioned studies have not only demonstrated the relevance of self-development socialization goals to Chinese as well as European-American parenting, but also provided initial support for the role of self-development socialization goals in shaping parenting behaviors fostering versus restraining offspring’s sense of self.

School Performance and Parental Autonomy Support and Psychological Control

Guided by transactional models of parental socialization, which recognize the direction of effects from offspring’s characteristics to parenting in addition to the other way around (for reviews, see Bell 1979; Belsky 1984; Sameroff and Mackenzie 2003), investigators have examined how offspring’s school performance may shape parenting behaviors granting autonomy versus exerting control (see Grolnick 2003; Pomerantz et al. 2005). In a study among fourth to sixth graders and their mothers in the US (mostly European Americans), Pomerantz and Eaton (2001) showed that the lower children’s grades in major school subjects, the less autonomy supportive 6 months later were their mothers in the homework context, in that their mothers would check and help with their homework without their request. In a study among third graders and their mothers in the US (mostly European Americans), Grolnick et al. (2002) showed that mothers of children with lower grades were less autonomy supportive when interacting with their children during school-like tasks in the laboratory (e.g., forcing directives on children instead of encouraging children to figure out solutions by themselves). The study by Pomerantz and Eaton (2001) further identified an underlying mechanism such that children’s poor school performance made their mothers worry and feel pressured to push and help them, and in turn become less autonomy supportive.

Although the links from school performance to autonomy-supportive versus controlling parenting behaviors have yet to be demonstrated exactly among families of adolescent offspring, the foregoing mechanism may well be at work similarly or even more vigorously during the secondary-school years, when academic success is of greater concern than during the elementary-school years. Notably, as Chinese parents assume utmost responsibility to boost their offspring’s educational achievement (see Chao and Tseng 2002; Wu 1996), they may be particularly likely to feel worried and pressured when their offspring are not doing well at school, and then readily fall back on less autonomy-supportive but more controlling parenting behaviors. Indeed, consistent with the notion that Chinese parents tend to consider psychological control as an effective socialization tool to motivate their offspring to meet societal standards (e.g., doing well at school), Wang and Pomerantz (2008) found that the greater decrease in Chinese adolescents’ grades as they progressed through the first 2 years in middle school, the more psychologically controlling they reported their parents to be at the end of these 2 years. To summarize, the aforementioned studies have shown school performance as a direct determinant of parental autonomy support and psychological control, given the typical parental concern over offspring’s academic success. It is interesting to note that while the study by Pomerantz and Eaton (2001) as well as the study by Grolnick et al. (2002) demonstrated American parents’ lessened autonomy support and heightened control specifically concerning schoolwork in the face of their offspring’s poor school performance, the study by Wang and Pomerantz (2008) examined Chinese parents’ psychological control in general regardless of domains of adolescents’ life. The finding by Wang and Pomerantz (2008) of Chinese parents exerting increased psychological control in general given their adolescent offspring’s deteriorated school performance suggests that Chinese parents may consider schoolwork being influenced by other domains of adolescents’ life in which they also need to intervene. Indeed, there is evidence that peer groups play a role in Chinese adolescents’ academic achievement as being in a peer group of relatively better school performance on average highlights to adolescents the value of schoolwork (Chen et al. 2003). Chinese parents seem to be well aware of such functions of peer groups and may attempt to manage their offspring’s peer relations to ensure facilitating rather than interfering peer influences on their offspring’s schoolwork (Stevenson and Lee 1996). Hence, Chinese adolescents’ school performance may affect their parents’ autonomy support and psychological control concerning not only schoolwork but also peer relations.

The Interplay Between Self-Development Socialization Goals and School Performance

As their offspring enter adolescence and start secondary school, there may well be a tension among Chinese parents between their concerns over their offspring’s self development and academic success. On the one hand, Chinese parents may endorse self-development socialization goals for their adolescent offspring, which urge them to engage in autonomy support and refrain from psychological control. On the other hand, in the face of their offspring’s unsatisfactory school performance, Chinese parents may be overwhelmed with worry and pressure and then resort to less autonomy-supportive but more controlling parenting behaviors. These two forces of their self-development socialization goals and their offspring’s school performance may thus interact to shape Chinese parents’ parenting behaviors. Given the long-standing moral value placed on education in Chinese culture and the prominent pragmatic utility of academic success in contemporary China (see Pomerantz et al. 2008), despite growing attention to other developmental outcomes including a positive sense of self, school performance remains central in Chinese adolescents’ lives (see Fong 2004). Therefore, it is expected that when adolescents are doing well at school, parents’ self-development socialization goals may take over and foreshadow their heightened autonomy support and dampened psychological control. In contrast, when adolescents are doing poorly at school, parents’ self-development socialization goals may give way and have little influence on their parenting behaviors, which are likely to be lacking in autonomy support but awash with psychological control, out of parents’ attempts to push and help their offspring to improve at schoolwork and regardless of their self-development socialization goals.

Overview of the Current Research

This research aimed to test the hypothesis that Chinese parents’ endorsement of self-development socialization goals and their adolescent offspring’s school performance may interact to predict their autonomy support and psychological control concerning their offspring’s schoolwork as well as peer relations. In other words, we expected the links from parents’ self-development socialization goals to their autonomy-supportive and psychologically controlling parenting behaviors to be moderated by their adolescent offspring’s grades in major school subjects. Specifically, at relatively high levels of grades, self-development socialization goals may be related positively to parental autonomy support and related negatively to parental psychological control, whereas at relatively low levels of grades, self-development socialization goals may be unrelated to parental autonomy support and psychological control. We studied Chinese families of seventh graders, upon their entry into adolescence and secondary school when the issues of self development and academic success both gain importance (see Chen and Chang 2007; Chen et al. 2000). As a first step toward understanding antecedents of Chinese parents’ autonomy support and psychological control with their adolescent offspring in terms of parents’ socialization goals and adolescents’ school performance, the current research employed a cross-sectional design that involved parents reporting on socialization goals and adolescents reporting on parenting behaviors at one time point when adolescents were in seventh grade.

Method

Participants

Three hundred and forty-one seventh graders (197 females and 144 males; mean age = 13.30 years, SD = .47, with one adolescent missing reporting her age) and their parents (186 mothers and 155 fathers; mean age = 40.70, SD = 4.47, with 19 parents missing reporting their age) participated in this research. The participants were recruited through a public school in a big city in Southwestern China. Among 78 % of the families invited, one parent from each family provided written agreement for her/himself and the adolescent offspring to participate; the adolescent her/himself provided written assent. The participating parents reported their own educational level (among the 325 parents who provided this information about themselves, 5 % completed primary school = 1, 27 % completed middle school = 2, 30 % completed high school = 3, 23 % attained an associate degree = 4, 14 % attained a bachelor’s degree = 5, and 1 % attained a master’s degree = 6; mean = 3.18, SD = 1.15) as well as their spouses’ educational level (322 of the participating parents provided this information about their spouses, among whom 9 % completed primary school; 30 % completed middle school; 27 % completed high school; 18 % attained an associate degree; 15 % attained a bachelor’s degree; 1 % attained a master’s degree; mean = 3.03, SD = 1.25). Spousal educational levels were highly correlated, r = .70, p < .001; their mean was taken, with higher numbers representing higher parental education (mean = 3.11, SD = 1.11). Due to the rather sensitive nature of information on parents’ marital status (given the predominant societal value of family that tends to disapprove divorce) and number of offspring (given the governmental one-child-per-family policy) in China, we did not collect data about these aspects of the individual families. We only were able to estimate that our sample consisted of mostly intact families in which there was just one offspring, based on the general situation for the student body of the participating school.

Procedure

Adolescents brought home a set of parent questionnaires; for each family, at the parents’ choice, one of them completed the questionnaires, which were then returned to adolescents’ homeroom teachers. Adolescents completed a set of questionnaires in classroom sessions overseen by their homeroom teachers. Adolescents’ grades were obtained from school records. All completed questionnaires were sealed in envelopes by the respondents to ensure confidentiality. To minimize the demands on the participating families, we asked only one parent from each family to report on her/his own and the spouse’s endorsement of self-development socialization goals, and we asked the adolescent offspring from each family to report on both parents’ autonomy support and psychological control as a whole. Our decision on this economical yet valid design was supported by prior work. On the one hand, spousal reports on various aspects of parenting have been found to be consistent with self-reports in previous studies among parents of adolescents (e.g., Conger et al. 1995; Padilla-Walker and Christensen 2010). On the other hand, there has been evidence for both parents being quite consistent in parenting adolescents (e.g., Ferguson et al. 2010; Sher-Censor et al. 2011; for reviews, see Laursen and Collins 2009; Steinberg 2001), and adolescents’ reports on both parents’ autonomy support and psychological control as a whole have been used widely in prior work (e.g., Barber et al. 2005; Lekes et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2007).

Measures

All of the 341 participating families had complete data in terms of whole-measure scores as described below. However, within each measure across the individual items, there were missing points for zero to twenty families. The corresponding factor analyses or reliability analyses employed list-wise deletion in handling the missing data, and the corresponding whole-measure scores were computed for each family excluding the items with missing data.

Self-Development Socialization Goals

A 6-item measure was created in Chinese specifically for this research to assess parents’ endorsement of self-development socialization goals. The items (i.e., “It is very important that my child is happy and enjoys life”, “is optimistic and self-confident”, “feels good about him/herself”, “has her/his own opinions and ideas”, “is able to stand up for her/himself”, “is able to rely on her/himself.”) were selected from previous studies that have demonstrated the relevance of these socialization goals to Chinese parenting (Chao 2000; Li et al. 2010; Padmawidjaja and Chao 2010). The participating parents indicated the extent to which they agreed with each of the six items (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree) for their participating adolescent offspring; they also indicated their spouses’ agreement with these items based upon their perceptions. To verify that the six items represent socialization goals which Chinese parents would coherently endorse, we conducted Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) employing principal component extraction, separately with the participating parents’ self-reports and their reports on behalf of their spouses. For the former, a single factor with an eigen value greater than one (3.05) explained 50.78 % of the total variance, and the factor loadings of the six items on it ranged from .62 to .80; for the latter, a single factor with an eigen value greater than one (3.08) explained 51.30 % of the total variance, and the factor loadings of the six items on it ranged from .67 to .79. Moreover, the measure was internally reliable for both the participating parents’ self-reports (α = .79) and their reports on behalf of their spouses (α = .80). These results support the construct validity of the measure. The mean of the six items was taken for the participating parents’ self-reports (mean = 5.99, SD = .98) and their reports on behalf of their spouses (mean = 6.01, SD = .95). These two scores were highly correlated, r = .86, p < .001; their mean was taken, with higher numbers representing parents’ stronger endorsement of self-development socialization goals (mean = 6.00, SD = .93).

Autonomy Support and Psychological Control

Following prior work (e.g., Barber et al. 2005; Lekes et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2007), parents’ autonomy support and psychological control were reported by their adolescent offspring. Autonomy support concerning schoolwork and peer relations were assessed separately, each with eight items adapted from the Chinese version of the measure used by Wang et al. (2007; e.g., “My parents allow me to make choices about things related to school/with my friends whenever possible.” “My parents encourage me to give my ideas and opinions when it comes to decisions about my schoolwork/things with my friends.”). Adolescents indicated how true each item was of their parents (1 = not at all true; 5 = very true). The measures were internally reliable (αs = .91 and .93 for autonomy support concerning schoolwork and peer relations, respectively). The mean of the eight items was taken concerning schoolwork (mean = 3.32, SD = 1.05) and peer relations (mean = 3.48, SD = 1.08). These two scores were highly correlated, r = .66, p < .001; their mean was taken, with higher numbers representing greater parental autonomy support (mean = 3.40, SD = .97). Psychological control concerning schoolwork and peer relations were assessed separately, each with thirteen items adapted from the Chinese version of the measure used by Wang et al. (2007; e.g., “My parents tell me that I should feel guilty when I do not do as well in school as they expect me to/do as they expect about things related to my friends.” “My parents act cold and unfriendly if I do not study as much as they think I should/handle things related to my friends the way they think I should.”). Adolescents indicated how true each item was of their parents. The measures were internally reliable (αs = .90 and .94 for psychological control concerning schoolwork and peer relations, respectively). The mean of the thirteen items was taken concerning schoolwork (mean = 2.90, SD = .94) and peer relations (mean = 2.48, SD = 1.07). These two scores were highly correlated, r = .72, p < .001; their mean was taken, with higher numbers representing greater parental psychological control (mean = 2.69, SD = .93).

Grades

Adolescents’ grades in Chinese, math and English were obtained from school records. Grades were numerical, ranging from 0 to 150. The mean across the three subjects was taken, with higher numbers representing better school performance (mean = 107.86, SD = 17.01).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

We first examined the zero-order correlations among parents’ self-development socialization goals, parents’ autonomy support and psychological control, and adolescents’ school performance. Given that these aspects of parenting and adolescent functioning might differ for female versus male adolescents (see Leaper 2002), and vary across parents’ educational levels (see Hoff et al. 2002), we also examined the roles of adolescent sex and parental education. As shown in Table 1, adolescent sex was unrelated to parents’ self-development socialization goals, autonomy support or psychological control, while female adolescents outperformed male adolescents at school. Consistent with prior work (e.g., Chao 2000), parents with higher education were more likely to endorse self-development socialization goals. However, parental education was unrelated to parents’ autonomy support, psychological control or adolescents’ school performance. Parents’ endorsement of self-development socialization goals was related positively to their autonomy support while unrelated to their psychological control. Adolescents’ school performance was related positively to their parents’ autonomy support while related negatively to their parents’ psychological control.

Central Analyses

This research aimed to investigate how parents’ self-development socialization goals and adolescents’ school performance may jointly foreshadow parents’ autonomy support and psychological control. To this end, we conducted hierarchical multiple regression analyses, in which we predicted autonomy support or psychological control from self-development socialization goals and grades in the first step, and the interaction between these two predictors in the second step. Adolescent sex and parental education were unrelated to autonomy support or psychological control (see Table 1), and when they were included as covariates in the analyses, the results remained similar; thus, the central analyses excluded these two factors to be parsimonious. Following Aiken and West (1991), we mean-centered the two predictors in the analyses to obtain estimates representing the main effects of each predictor at the average level of the other predictor. We also followed Aiken and West (1991) to decompose significant interactions.

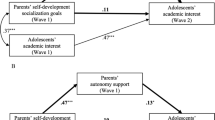

Predicting Autonomy Support

As shown in Table 2, consistent with prior work, there were significant main effects of parents’ self-development socialization goals, t(340) = 3.83, p < .001, and adolescents’ school performance, t(340) = 3.54, p < .001, on parents’ autonomy support, such that the stronger parents’ endorsement of self-development socialization goals or the higher adolescents’ grades, the greater parents’ autonomy support. Yet, there also was a significant interaction between self-development socialization goals and grades, t(340) = 2.33, p = .020. Decomposition of this interaction showed that parents’ endorsement of self-development socialization goals was related positively to their autonomy support only when adolescents had high (one standard deviation above the mean), t(340) = 4.19, p < .001, or average (the mean) grades, t(340) = 3.83, p < .001, not when adolescents had low (one standard deviation below the mean) grades, t(340) = 1.18, p = .239 (see Table 2). As shown in Fig. 1, only when adolescents were not falling behind at school did parents’ endorsement of self-development socialization goals positively predict their autonomy support, whereas when adolescents were falling behind at school, parents’ autonomy support was relatively low, regardless of their self-development socialization goals.

The relation from parental endorsement of self-development socialization goals to adolescent-reported parental autonomy support was moderated by adolescents’ grades. Note. Low levels of endorsement of self-development socialization goals and grades were 1 SD below the mean, average levels were at the mean, and high levels were 1 SD above the mean. Slopes were estimated from the central analyses. ps < .001 for the slopes at the average and high levels of grades

Predicting Psychological Control

As shown in Table 2, consistent with prior work, there was a significant main effect of adolescents’ school performance on parents’ psychological control, t(340) = −2.42, p = .016, such that the higher adolescents’ grades, the lesser parents’ psychological control, while parents’ self-development socialization goals had no significant main effect on their psychological control, t(340) = −1.13, p = .261. Yet, there also was a significant interaction between self-development socialization goals and grades, t(340) = −2.50, p = .013. Decomposition of this interaction showed that parents’ endorsement of self-development socialization goals was related negatively to their psychological control only when adolescents had high grades, t(340) = −2.44, p = .015, not when adolescents had average, t(340) = −1.13, p = .261, or low grades, t(340) = .98, p = .328 (see Table 2). As shown in Fig. 2, only when adolescents were excelling at school did parents’ endorsement of self-development socialization goals negatively predict their psychological control, whereas when adolescents were not excelling at school, parents’ psychological control was relatively high, regardless of their self-development socialization goals.

The relation from parental endorsement of self-development socialization goals to adolescent-reported parental psychological control was moderated by adolescents’ grades. Note. Low levels of parental endorsement of self-development socialization goals and grades were 1 SD below the mean, average levels were at the mean, and high levels were 1 SD above the mean. Slopes were estimated from the central analyses. p < .05 for the slope at the high level of grades

Supplemental Analyses

In the current research, we obtained adolescents’ reports on both parents’ autonomy support and psychological control as a whole without differentiating maternal versus paternal parenting within each family. Yet, there were self-reports by mothers and fathers from different families on their endorsement of self-development socialization goals, allowing analyses to explore the role of parental gender in the links among parents’ socialization goals, adolescents’ school performance, and parents’ autonomy support and psychological control. To this end, we first examined the zero-order correlations between the participating parents’ gender and the other constructs. It turned out that the participating parents’ gender was unrelated to their self-reported endorsement of self-development socialization goals, their offspring’s school performance, or their offspring’s reports on their and their spouses’ autonomy support or psychological control as a whole, |r|s < .06, ps > .33. Next, we conducted hierarchical multiple regression analyses, in which we predicted adolescents’ reports on both parents’ autonomy support or psychological control from the participating parents’ gender, their self-reported socialization goals and adolescents’ grades in the first step, the 2-way interactions of each pair of these three predictors in the second step, and the 3-way interaction of all predictors in the third step. None of the main or interactive effects involving parental gender was significant, |t|s (340) < 1.79, ps > .07. Regardless of their gender, the participating parents’ self-reported endorsement of self-development socialization goals interacted with their offspring’s grades in predicting their autonomy support, b = .10, SE = .05, β = .10, t(340) = 1.93, p = .054, and psychological control, b = −.12, SE = .05, β = −.13, t(340) = −2.35, p = .020, similar to the results from the central analyses examining both parents’ socialization goals and their autonomy support or psychological control as a whole.

Discussion

To our best knowledge, no previous studies specifically have investigated antecedents of Chinese parents’ autonomy support and psychological control, which represents a serious gap, given the vital consequences of these parenting dimensions for Chinese adolescents’ development (e.g., Barber et al. 2005; Lekes et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2007). The current research sought to fill in this gap. Guided by the idea that there may be a tension between Chinese parents’ concerns over their adolescent offspring’s self development and academic success, we examined the interplay between parents’ self-development socialization goals and adolescents’ school performance in predicting Chinese parents’ autonomy support and psychological control. We found that when adolescents were doing well at school, the stronger Chinese parents’ endorsement of self-development socialization goals, the greater their autonomy support and the lesser their psychological control, whereas when adolescents were doing poorly at school, Chinese parents were relatively less autonomy supportive but more psychologically controlling, regardless of their self-development socialization goals. These findings have noteworthy theoretical and practical implications.

Theoretically, first of all, the interactions revealed in this research between parents’ self-development socialization goals and adolescents’ school performance in predicting parents’ autonomy support and psychological control provide evidence for transactional models of parental socialization that emphasize the joint roles of parent and offspring characteristics in determining parenting behaviors (see Bell 1979; Belsky 1984; Sameroff and Mackenzie 2003). Moreover, the moderating effects demonstrated in this research of adolescents’ school performance on the links from parents’ self-development socialization goals to their autonomy support and psychological control suggest a promising direction to solve the “puzzle” pertaining to frequently found weak or inconsistent connections between parental cognitions and parenting behaviors (see Bugental and Johnston 2000; Goodnow 1988). Namely, it may be worthwhile to look for moderators including offspring characteristics that may facilitate or hinder the translation from parental cognitions into parenting behaviors (see also Sameroff and Mackenzie 2003).

Second, the findings of this research shed light on two theoretical queries about the role of culture in parental socialization. For one, to what extent do individualistic socialization goals exist and how may they make a difference in contemporary parenting in traditionally collectivist cultures such as Chinese societies (see Tamis-LeMonda et al. 2008)? For another, to what extent may there be a tension between individualistic socialization goals and other cultural precepts about parenting in traditionally collectivist cultures such as Chinese societies, and how parents may balance concerns that are in tension with each other in their parenting behaviors (see Grusec and Rudy 2001)? This research showed that parents in contemporary China coherently endorsed individualistic socialization goals (i.e., regarding a positive sense of self manifested in optimistic attitudes toward oneself, autonomy in one’s actions, and independence from others, as important for their adolescent offspring to develop). Moreover, their endorsement of such self-development socialization goals was predictive of their parenting behaviors in terms of autonomy support and psychological control, depending on their offspring’s school performance. There indeed seems to be a tension between Chinese parents’ self-development socialization goals and the culturally prescribed responsibility for them to ensure their offspring’s academic success. When adolescents were doing well at school, parents’ endorsement of self-development socialization goals positively predicted their autonomy support and negatively predicted their psychological control. In contrast, when adolescents were doing poorly at school, parents’ endorsement of self-development socialization goals was unrelated to their parenting behaviors, which were then characterized by dampened autonomy support and heightened psychological control, presumably due to parents’ concern over their offspring’s academic success. As expected, Chinese parents’ autonomy support or psychological control concerning their adolescent offspring’s schoolwork and peer relations were associated closely with each other. This is consistent with the observation that Chinese parents tend to view peer relations as influential on adolescents’ academic achievement and thus may intervene in the domains of both schoolwork and peer relations to ensure their offspring’s academic success (Stevenson and Lee 1996). Taken together, the findings of the current research echo calls not to dichotomize cultures as individualistic versus collectivist, and illustrate how parents’ concerns over universal developmental needs (e.g., a positive sense of self) and cultural imperatives (e.g., academic success) may interact to foreshadow their parenting behaviors.

Practically, on the one hand, this research demonstrated a positive link from self-development socialization goals to autonomy support and a negative link from self-development socialization goals to psychological control among Chinese parents of adolescents, when adolescents were doing well at school. On the other hand, this research revealed that when their adolescent offspring were doing poorly at school, Chinese parents engaged in parenting behaviors lacking in autonomy support but awash with psychological control, regardless of their self-development socialization goals. These findings highlight the importance of making the following efforts when advising and educating parents of adolescents to eventually foster adolescents’ well-being. First, given the links from self-development socialization goals to heightened autonomy support and dampened psychological control among Chinese parents of adolescents (at least when adolescents are doing well at school), such socialization goals need to be advocated vigorously. Second, it is essential to inform parents forcefully about the positive effects of autonomy support but negative effects of psychological control on adolescent development, so that even when in the face of worry and pressure to push and help their adolescent offspring to improve on their schoolwork, they would not fall back on decreased autonomy support and increased psychological control, which may be well-intentioned but actually backfire (see Grolnick 2003). Third, alternative ways to help low-achieving adolescents constructively, rather than counterproductively, need to be introduced to parents, such as non-intrusive involvement in schoolwork, which is in accordance, rather than in tension, with self-development socialization goals (see Grolnick 2003; Pomerantz et al. 2005).

The current research had several strengths but also some limitations, leaving open questions for future work. First, moving beyond most previous studies relying on either parents or adolescents as a single source of information, this research obtained parents’ reports on their own and their spouses’ endorsement of self-development socialization goals, adolescents’ reports on both parents’ autonomy support and psychological control as a whole, and adolescents’ grades from school records as an objective indicator of their academic performance. Such a design considerably helps to reduce the influences of potential response biases (e.g., adolescents may be less biased than their parents in reporting socially undesirable parenting behaviors like psychological control; Gonzales et al. 1996) and the problem of common-method variance, thereby enhancing the validity of the findings. However, this research was cross-sectional, calling for longitudinal and experimental studies in the future to pinpoint the direction of effects from parents’ endorsement of self-development socialization goals and adolescents’ school performance to parents’ autonomy support and psychological control, rather than vice versa. Notably, transactional models of parental socialization (see Bell 1979; Belsky 1984; Sameroff and Mackenzie 2003) and previous longitudinal studies (e.g., Pomerantz and Eaton 2001; Wang and Pomerantz 2008) indeed have lent quite strong theoretical and empirical support for the role of adolescents’ school performance as an antecedent, besides being a consequence, of parenting behaviors such as autonomy support and psychological control. Future longitudinal and experimental studies will be particularly useful for examining the links from parents’ socialization goals to their parenting behaviors when adolescents’ school performance dynamically shifts for better or for worse. This will make a significant improvement on the current cross-sectional research, which was only able to investigate the links from parents’ socialization goals to their parenting behaviors when adolescents’ school performance was statically good or poor in comparison to their schoolmates.

Second, this research employed an economical yet valid design in which one parent from each participating family reported on her/his own and the spouse’s socialization goals, and the adolescent offspring reported on both parents’ parenting behaviors as a whole. The analyses allowed by such a design to explore the role of the participating parents’ gender in the links among their self-reported socialization goals, their offspring’s school performance, and their offspring’s reports on their and their spouses’ parenting behaviors as a whole revealed little evidence for differences between mothers and fathers. However, future studies should differentiate maternal and paternal parenting exactly by having separate reports on mothers’ and fathers’ socialization goals as well as parenting behaviors from multiple informants including mothers and fathers themselves, their spouses, and their offspring. Such studies are necessary to test the possibility that Chinese mothers and fathers may play different roles in socializing their adolescent offspring (e.g., mothers may assume greater responsibility for adolescents’ schoolwork while fathers may assume greater responsibility for adolescents’ development of autonomy and independence; Chen and He 2005).

Third, this research attended to the relevant demographic factor of parental education and studied a sample of families varying sizably on this factor. Nevertheless, the sample was quite homogeneous in terms of being urban and including mostly intact families with only offspring. Potential variations across families differing in parental marital status and number of offspring, as well as between urban and rural families in contemporary China need to be investigated. Such demographic and regional variations may exist in the weights that parents place on adolescents’ development of a positive sense of self versus academic success, and parents’ beliefs about how their parenting behaviors may affect adolescents’ development. Hence, it is of interest to replicate this research among more heterogeneous samples from both urban and rural areas in China. For example, given greater respect for parental authority in rural (vs. urban) areas (e.g., Zhang and Fuligni 2006), there may be mean-level differences in parents’ socialization goals and parenting behaviors, such that in comparison to their urban counterparts, rural parents endorse self-development socialization goals and use autonomy support to a lesser extent, while use psychological control to a greater extent. Moreover, the links from parents’ endorsement of self-development socialization goals to their autonomy support and psychological control generally may be weaker among rural (vs. urban) parents. These possible urban–rural differences need to be examined in the future.

Similarly, it remains an empirical question of whether the interplay between parents’ endorsement of self-development socialization goals and adolescents’ school performance in predicting parents’ autonomy support and psychological control revealed in this research may be evident in prototypically individualistic cultures such as many Western societies. It is possible that self development in Western societies is valued to such a great extent that parents’ self-development socialization goals easily can prevail over the pressure for them to push and help their offspring to succeed academically, which tends to be less of a cultural imperative than in Chinese societies; thus, regardless of adolescents’ school performance, parents’ endorsement of self-development socialization goals may foreshadow their increased autonomy support and deceased psychological control. However, given prior work showing Western parents reacting to their offspring’s poor school performance with relatively less autonomy-supportive but more controlling parenting behaviors (e.g., Grolnick et al. 2002; Pomerantz and Eaton 2001), it is likely that there also exits a tension between parents’ concerns over their offspring’s self development and academic success in Western societies. Therefore, the findings of this research that the links from parents’ endorsement of self-development socialization goals to their autonomy support and psychological control are moderated by adolescents’ school performance may be evident in Western societies as well.

Lastly, the current research focused on self-development socialization goals that have been theorized to foreshadow parental autonomy support and psychological control across cultures (see Barber and Harmon 2002; Grolnick 2003). Yet, to comprehensively understand antecedents of Chinese parents’ autonomy-supportive and psychologically controlling parenting behaviors with their adolescent offspring, it is important to also examine socialization goals which are indigenous to Chinese culture. For example, it may be the case that when parents endeavor to cultivate filial piety in their adolescent offspring, which entails excelling at school to honor one’s family (see Chao 2000), they are particularly likely to be concerned about their offspring’s academic success, and thus react to their offspring’s poor school performance with dampened autonomy support and heightened control. Future studies simultaneously investigating parents’ endorsements of diverse socialization goals will contribute to a better understanding of how parental socialization in contemporary China is shaped by Chinese culture that is multifaceted and undergoes continuity as well as changes.

Conclusion

This research took a fruitful first step to explore antecedents of Chinese parents’ autonomy support and psychological control with their adolescent offspring. The findings show that as contemporary Chinese parents balance their concerns over their adolescent offspring’s self development and academic success, parents’ endorsement of self-development socialization goals and adolescents’ school performance interact to predict parenting behaviors. Only when adolescents are doing well at school, does parents’ endorsement of self-development socialization goals foreshadow their increased autonomy support and decreased psychological control, whereas when adolescents are doing poorly at school, parents’ endorsement of self-development socialization goals is unrelated to parenting behaviors, which tend to be lacking in autonomy support but awash with psychological control. To promote autonomy support and prevent psychological control among Chinese parents and eventually foster their adolescent offspring’s well-being, not only do self-development socialization goals need to be advocated, but also alternative parenting behaviors other than dampened autonomy support and heightened psychological control in reaction to adolescents’ poor school performance need to be tutored.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Arim, R. G., & Shapka, J. D. (2008). The impact of pubertal timing and parental control on adolescent problem behaviors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37, 445–455. doi:10.1007/s10964-006-9158-y.

Barber, B. K., & Harmon, E. L. (2002). Violating the self: Parental psychological control of children and adolescents. In B. K. Barber (Ed.), Intrusive parenting: How psychological control affects children and adolescents (pp. 15–52). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. doi:10.1037/10422-002.

Barber, B. K., Stolz, H. E., & Olsen, J. A. (2005). Parental support, psychological control, and behavioral control: Assessing relevance across time, culture, and method. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 70 (4, Serial No. 282). doi:10.1111/j.1540-5834.2005.00365.x.

Barber, B. K., Xia, M., Olsen, J. A., McNeely, C. A., & Bose, K. (in press). Feeling disrespected by parents: Refining the measurement and understanding of psychological control. Journal of Adolescence. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.10.010.

Bell, R. Q. (1979). Parent, child, and reciprocal influences. American Psychologist, 10, 821–826. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.821.

Belsky, J. (1984). The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development, 55, 83–96. doi:10.2307/1129836.

Brenning, K., Soenens, B., Braet, C., & Bal, S. (2011). The role of parenting and mother-adolescent attachment in the intergenerational similarity of internalizing symptoms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. doi:10.1007/s10964-011-9740-9.

Bugental, D. B., & Grusec, J. E. (2006). Socialization processes. In N. Eisenberg (Vol. Ed), W. Damon, & R. M. Learner (Series Eds.). Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., pp. 366–428). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Bugental, D. B., & Johnston, C. (2000). Parental and child cognitions in the context of the family. Annual Review of Psychology, 51, 315–344. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.315.

Chao, R. K. (2000). The parenting of immigrant Chinese and European American mothers: Relations between parenting styles, socialization goals, and parental practices. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 21, 233–248. doi:10.1016/S0193-3973(99)00037-4.

Chao, R., & Tseng, V. (2002). Parenting of Asians. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Vol. 4. Social conditions and applied parenting (2nd ed., pp. 59–93). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Chen, X., & Chang, L. (2007). China, People’s Republic of. In J. J. Arnett (Ed.), International encyclopedia of adolescence (pp. 179–194). Florence, KY: Routledge.

Chen, X., Chang, L., & He, Y. (2003). The peer group as a context: Mediating and moderating effects on relations between academic achievement and social functioning in Chinese children. Child Development, 74, 710–727. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00564.

Chen, X., Chen, H., Kaspar, V., & Noh, S. (2000). Adolescent social, emotional, and school adjustment in Mainland China. International Journal of Group Tensions, 29, 51–78. doi:10.1023/A:1005178713623.

Chen, X., & He, Y. (2005). The family in mainland China: Structure, organization, and significance for child development. In J. L. Roopnarine & U. P. Gielen (Eds.), Families in global perspective (pp. 51–62). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Conger, R. D., Patterson, G. R., & Ge, X. (1995). It takes two to replicate: A mediational model for the impact of parents’ stress on adolescent adjustment. Child Development, 66, 80–97. doi:10.2307/1131192.

Darling, N., & Steinberg, L. (1993). Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin, 113, 487–496. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.113.3.487.

Doyle, A. B., & Markiewicz, D. (2005). Parenting, marital conflict and adjustment from early- to mid-adolescence: Mediated by adolescent attachment style? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34, 97–110. doi:10.1007/s10964-005-3209-7.

Ferguson, Y. L., Kasser, T., & Jahng, S. (2010). Differences in life satisfaction and school satisfaction among adolescents from three nations: The role of perceived autonomy support. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21, 649–661. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00698.x.

Fong, V. L. (2004). Only hope: Coming of age under China’s one-child policy. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Foster, C. E., Webster, M. C., Weissman, M. M., Pilowsky, D. J., Wickramaratne, P. J., Rush, A. J., et al. (2008). Course and severity of maternal depression: Associations with family functioning and child adjustment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37, 906–916. doi:10.1007/s10964-007-9216-0.

Gonzales, N. A., Cauce, A. M., & Mason, C. A. (1996). Interobserver agreement in the assessment of parental behavior and parent-adolescent conflict: African American mothers, daughters, and independent observers. Child Development, 67, 1483–1498. doi:10.2307/1131713.

Goodnow, J. J. (1988). Parents’ ideas, actions, and feelings: Models and methods from developmental and social psychology. Child Development, 59, 286–320. doi:10.2307/1130312.

Gray, M. R., & Steinberg, L. (1999). Unpacking authoritative parenting: Reassessing a multidimensional construct. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61, 574–587. doi:10.2307/353561.

Grolnick, W. S. (2003). The psychology of parental control: How well-meant parenting backfires. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Grolnick, W. S., Gurland, S. T., DeCourcey, W., & Jacob, K. (2002). Antecedents and consequences of mothers’ autonomy support: An experimental investigation. Developmental Psychology, 38, 143–155. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.38.1.143.

Grusec, J. E., & Rudy, D. (2001). Culture and parenting: Expanded horizons. International Society for the Study of Behavioral Development Newsletter, 1(Serial No. 38), 16.

Hoff, E., Laursen, B., & Tardif, T. (2002). Socioeconomic status and parenting. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Vol. 2. Biology and ecology of parenting (2nd ed., pp. 231–252). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Laursen, B., & Collins, W. A. (2009). Parent-child relationships during adolescence. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescence psychology: Vol. 2. Contextual influences on adolescent development (3rd ed., pp. 3–42). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Leaper, C. (2002). Parenting girls and boys. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Vol. 1. Children and parenting (2nd ed., pp. 189–225). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Lekes, N., Gingras, I., Philippe, F. L., Koestner, R., & Fang, J. (2010). Parental autonomy support, intrinsic life goals, and well-being among adolescents in China and North America. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 858–869. doi:10.1007/s10964-009-9451-7.

Li, Y., Costanzo, P. R., & Putallaz, M. (2010). Maternal socialization goals, parenting styles, and social-emotional adjustment among Chinese and European American young adults: Testing a mediation model. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 171, 330–362. doi:10(1080/00221325),2010,505969.

Loukas, A., Paulos, S. K., & Robinson, S. (2005). Early adolescent social and overt aggression: Examining the roles of social anxiety and maternal psychological control. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34, 335–345. doi:10.1007/s10964-005-5757-2.

Miller, S. R., Tserakhava, V., & Miller, C. J. (2011). My child is shy and has no friends: What does parenting have to do with it? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 442–452. doi:10.1007/s10964-010-9550-5.

Padilla-Walker, L. M., & Christensen, K. J. (2010). Empathy and self-regulation as mediators between parenting and adolescents’ prosocial behavior toward strangers, friends, and family. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21, 545–551. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00695.x.

Padmawidjaja, I. A., & Chao, R. K. (2010). Parental beliefs and their relation to the parental practices of immigrant Chinese Americans and European Americans. In S. T. Rusell, L. J. Crokett, & R. K. Chao (Eds.), Asian American parenting and parent-adolescent relationships (pp. 37–60). New York, NY: Springer.

Pomerantz, E. M., & Eaton, M. M. (2001). Maternal intrusive support in the academic context: Transactional socialization processes. Developmental Psychology, 37, 174–186. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.37.2.174.

Pomerantz, E. M., Ng, F. F., & Wang, Q. (2008). Culture, parenting, and motivation: The case of East Asia and the United States. In M. L. Maehr, S. A. Karabenick, & T. C. Urdan (Eds.), Advances in motivation and achievement: Vol. 15. Social psychological perspectives (pp. 209–240). Bingley, UK: Emerald Group.

Pomerantz, E. M., Wang, Q., & Ng, F. F-Y. (2005). The role of children’s competence experiences in the socialization process: A dynamic process framework for the academic arena. In R. Kail (Ed.), Advances in child development and behavior (Vol. 33, pp. 193–227). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. doi:10.1016/S0065-2407(05)80008-4.

Rudy, D., Awong, T., & Lambert, M. (2008). Parental psychological control and authoritarianism in Chinese-Canadian and European-Canadian cultural groups: Their meanings and implications for university students’ adjustment. Journal of Comparative Family Issues, 39, 471–490.

Sameroff, A. J., & Mackenzie, M. J. (2003). Research strategies for capturing transactional models of development: The limits of the possible. Development and Psychopathology, 15, 613–640. doi:10.1017/S0954579403000312.

Seiffge-Krenke, I., & Pakalniskiene, V. (2011). Who shapes whom in the family: Reciprocal links between autonomy support in the family and parents’ and adolescents’ coping behaviors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 383–995. doi:10.1007/s10964-010-9603-9.

Shek, D. T. (2007). A longitudinal study of perceived parental psychological control and psychological well-being in Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 63, 1–22. doi:10.1002/jclp.20331.

Sher-Censor, E., Parke, R. D., & Coltrane, S. (2011). Parents’ promotion of psychological autonomy, psychological control, and Mexican-American adolescents’ adjustment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 620–632. doi:10.1007/s10964-010-9552-3.

Smetana, J. G., Campione-Barr, N., & Metzger, A. (2006). Adolescent development in interpersonal and societal contexts. Annual Review of Psychology, 57, 255–284. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190124.

Soenens, B., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2005). Antecedents and outcomes of self-determination in 3 life domains: The role of parents’ and teachers’ autonomy support. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34, 589–604. doi:10.1007/s10964-005-8948-y.

Steinberg, L. (1990). Autonomy, conflict, and harmony in the family relationship. In S. S. Feldman & G. R. Elliott (Eds.), At the threshold: The developing adolescent (pp. 255–276). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Steinberg, L. (2001). We know some things: Parent-adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 11, 1–19. doi:10.1111/1532-7795.00001.

Stevenson, H. W., & Lee, S. Y. (1996). The academic achievement of Chinese students. In M. H. Bond (Ed.), The handbook of Chinese psychology (pp. 124–142). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Way, N., Hughes, D., Yoshikawa, H., Kalman, R. K., & Niwa, E. Y. (2008). Parents’ goals for children: The dynamic coexistence of individualism and collectivism in cultures and individuals. Social Development, 17, 183–209. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00419.x.

Vansteenkiste, M., Zhou, M., Lens, W., & Soenens, B. (2005). Experiences of autonomy and control among Chinese learners: Vitalizing or immobilizing? Journal of Educational Psychology, 97, 468–483. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.97.3.468.

Wang, Q., & Pomerantz, E. M. (2008). Transactions between early adolescents’ achievement and parent’s psychological control: A longitudinal investigation in China and the US. Symposium paper presented at the 20th biennial meeting of International Society of the Study of Behavioral Development. Germany: Würzburg.

Wang, Q., Pomerantz, E., & Chen, H. (2007). The role of parents’ control in early adolescents’ psychological functioning: A longitudinal investigation in the United States and China. Child Development, 78(5), 1592–1610. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01085.x.

Wu, D. Y. H. (1996). Chinese childhood socialization. In M. H. Bond (Ed.), The handbook of Chinese psychology (pp. 143–154). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Zhang, W., & Fuligni, A. (2006). Authority, autonomy, and family relationships among adolescents in urban and rural China. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 16, 527–537. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2006.00506.x.

Acknowledgments

Data collection for this research was supported by Direct Grant 2020938 of the Chinese University of Hong Kong; data management and literature search were supported by General Research Fund 451809 of Hong Kong Research Grants Council. We thank all participating parents and adolescents, and Eva M. Pomerantz, Florrie Fei-Yin Ng, Cecilia Sin-Sze Cheung, and Lili Qin for their valuable feedback on an earlier version of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Q., Chan, HW. & Lin, L. Antecedents of Chinese Parents’ Autonomy Support and Psychological Control: The Interplay Between Parents’ Self-Development Socialization Goals and Adolescents’ School Performance. J Youth Adolescence 41, 1442–1454 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9760-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9760-0