Abstract

The relative nature of pubertal timing has received little attention in research linking early pubertal development with psychological adjustment. The current study examines the dynamic association between pubertal timing and internalizing symptoms among an urban, ethnically diverse sample of girls (n = 1,167; 50% Latina, 30% Black/African American, 11% Asian, 9% White). By relying on six waves of data, we detected substantial within-person variability in pubertal timing, which in turn related to fluctuations in depressive symptoms, global self-worth, and social anxiety in multilevel analyses. Within-person changes in the direction of more advanced development compared to peers consistently predicted more depressive symptoms; however, more advanced development was related to lower self-worth only at the beginning of middle school. By the end of middle school, less advanced development predicted social anxiety. Results challenge the notion that pubertal timing is a stable individual characteristic, with implications for studying the psychosocial correlates of pubertal development across multiple years.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Adolescence is a time of change in the biological, social and psychological landscapes of individuals’ lives. Pubertal development, a hallmark change of adolescence, has been the focus of much research attention and its association with adolescent adjustment, particularly among girls, has been well documented. Mounting evidence suggests that pubertal timing—whether the pubertal process is occurring early, on-time, or late relative to peers—is associated with heightened psychological distress among adolescent girls. More specifically, experiencing puberty much earlier than one’s peers has been linked with internalizing disorders such as major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and social phobia (see Graber et al. 1997, 2004; Hayward et al. 1997), as well as subclinical symptoms, such as depressed mood, low self-worth, poor coping skills, and anxiety (Ge et al. 2001, 2006a; Nadeem and Graham 2005; Siegel et al. 1999; Zehr et al. 2007). However, with a few notable exceptions, most studies supporting such findings have either: been conducted with primarily Caucasian samples; focused on adolescents from middle class backgrounds; been conducted in rural or suburban neighborhoods; and/or relied heavily on cross-sectional data. Further investigation, therefore, is required to allow generalization of findings to more socioeconomically and ethnically diverse samples and to test the early pubertal timing model across multiple time points.

The purpose of the current study is to examine whether pubertal timing is associated with internalizing symptoms among a sample of ethnically diverse girls residing in primarily low socioeconomic status (SES) urban neighborhoods across 3 years. We not only test the early timing model among a population underrepresented in existing work, but also examine pubertal timing more dynamically than in past studies that relied on only one or two data points. The current study challenges the notion that pubertal timing is a stable individual characteristic by using six waves of data collected across the 3 years of middle school to investigate potential changes in pubertal timing as girls transition through early adolescence. Seeking to better understand the nuances of how physical maturation and adjustment are related over time and whether those associations hold true for girls typically underrepresented in the literature, we hope to contribute to the ongoing investigation of girls’ increased vulnerability to internalizing symptoms during adolescence.

A Need for Research with Ethnically Diverse, Urban Samples

Although most of the foundational research on pubertal timing has been conducted with Caucasian adolescents (for a review see Mendle et al. 2007), a small body of research examines the psychosocial correlates of early pubertal maturation among girls from racial and ethnic minority backgrounds. For instance, Ge and colleagues have found that early maturation is linked to both internalizing and externalizing symptoms among African American adolescents (Ge et al. 2002, 2003, 2006a) and Nadeem and Graham (2005) reported an association between early maturation and depressive symptoms among Latina and African American girls in sixth grade. However, at least one study found no difference in depressive symptoms across pubertal timing groups among Latina and African American girls in fifth through eighth grades (Hayward et al. 1999). Further research is needed to clarify these inconsistent findings, particularly among urban samples as much of the work examining pubertal timing and internalizing symptoms in ethnically diverse samples has been conducted with adolescents from rural and suburban neighborhoods (Ge et al. 2002, 2003, 2006a).

The small amount of research that has examined pubertal timing and adjustment among urban, ethnic minority samples has focused almost exclusively on externalizing problems. Findings indicate that early maturing African American and Latina girls report more aggression and delinquent behavior compared to their on-time and late maturing peers (Carter et al. 2009, 2010; Lynne et al. 2007). In fact, some evidence suggests that it is only among girls residing in urban environments or neighborhoods characterized by concentrated disadvantage that early maturation is a risk factor for externalizing behavior (Dick et al. 2000; Obeidallah et al. 2004). Given such findings for externalizing problems, it is surprising that so few studies have focused on pubertal timing and internalizing symptoms among urban adolescents. We hope to address this gap by examining pubertal timing group differences in internalizing symptoms among a large, ethnically diverse sample of girls attending public middle schools in an urban environment.

A Dynamic View of the Early Timing Model

Although much of the literature on pubertal timing is based on cross-sectional research, a number of longitudinal studies support the early timing model. In a landmark set of studies, Graber et al. (1997, 2004) found that, compared to on-time maturation, early pubertal timing in high school was associated with a higher lifetime prevalence of depressive and anxiety disorders among a subset of participants followed to young adulthood (age 24). Even in such prospective research, however, pubertal timing is typically determined based on pubertal development indicators at baseline and used to predict both concurrent and future internalizing symptoms. In another example, pubertal timing data were collected when girls were 10–12 years of age and then girls were re-assessed 6 years later for clinically significant psychiatric disorders (Jin et al. 2008). Those who were ultimately diagnosed with one or more internalizing disorder, compared to girls with no psychiatric diagnosis, had reported significantly earlier maturation at the first time point. In addition, Ge et al. (2001) found that early maturation reported in the seventh grade was associated with elevated symptoms of depression and that this trend persisted throughout secondary school. The authors concluded that pubertal timing is critical in predicting depressive symptoms throughout high school, particularly when measured at a time when maturational differences between groups are most noticeable (e.g., seventh grade).

The latter point brings up an interesting and often overlooked issue in the measurement of pubertal timing. Given that pubertal timing is an inherently relative construct, measured via comparisons among adolescents of similar age, maturational timing classifications can conceivably vary within individuals over the course of development. For instance, a girl might begin showing signs of puberty before most of her peers, but then develop relatively slowly, resulting in her peers “catching up.” Such a girl might be classified as early maturing if assessed at the start of puberty, but classified as on-time maturing if assessed at a later date. Individual differences in the rate, or tempo, of pubertal development are widely acknowledged (e.g., Susman and Dorn 2009) and could, thus, be a factor in determining a girl’s relative maturational standing compared to peers from one time point to the next.

Ge and colleagues have begun to examine this idea by assessing pubertal development at two different waves and separately examining associations between the resulting pubertal timing classifications and internalizing symptoms. In one of the only studies of its kind, pubertal timing was assessed in both the 5th and the 7th grade among a sample of African American adolescents (Ge et al. 2003). Each individual had two pubertal timing classifications, corresponding to the two waves, and these classifications did not necessarily have to match. In fact, findings indicated that some adolescents did, indeed, change pubertal timing groups from one wave to the next and that changes in pubertal timing categories were associated with depressive symptoms. Among girls, being classified as early maturing in 5th grade was linked with greater risk for depressive symptoms, both concurrently as well as 2 years later in 7th grade. Girls who were classified as early maturing in 7th grade—regardless of whether or not they were classified as early maturing in 5th grade—also showed higher depressive symptoms in 7th grade. Among boys, it appeared that within-person shifts in pubertal timing classification from 5th to 7th grade were associated with shifts in depressive symptoms. That is, boys who were relatively more developed than peers in 7th grade compared to when they were in 5th grade (e.g., categorized as on-time maturing in 5th grade and early maturing in 7th) showed the sharpest increases in depressive symptoms across the two waves; whereas boys who were relatively less developed than peers in 7th grade compared to when they were in 5th grade showed the sharpest decreases in depressive symptoms across waves. It is somewhat difficult to interpret these results, especially given that pubertal timing was measured at an age at which we wouldn’t expect much change in physical development among boys. Nonetheless, findings from this study are quite groundbreaking in showing that not only can pubertal timing classifications change from one point in time to the next, but also that such changes might be related to shifts in depressive symptoms. They also raise many questions regarding the measurement of pubertal timing as well as the nature of the association between pubertal timing and adjustment.

The Current Study

The goal of the current study is to better understand the dynamics of the association between pubertal timing and girls’ internalizing symptoms as they transition through the emotionally “risky” period of early adolescence. As part of this goal, we examine several internalizing symptom outcomes. Although often co-morbid, there exists evidence justifying a distinction between subtypes of internalizing symptoms and researchers have called for increased precision in their measurement vis-à-vis pubertal timing (Reardon et al. 2009). Heeding this call, we separately examine depressive symptoms, social anxiety, and global self-worth as internalizing outcomes. We are particularly interested in social-oriented forms of anxiety because pubertal timing itself is an inherently social construct requiring comparisons among peers. Because there exists limited empirical evidence to suggest that findings may differ by outcome, our approach here is exploratory. For ease of presentation, the three distinct outcomes of depressive symptoms, social anxiety, and global self-worth will be referred to as “internalizing symptoms” in the following description.

Two approaches to modeling the link between pubertal development and internalizing symptoms are taken in the current study. First, as is traditional in the literature, pubertal timing groups were formed at the first wave of the study (the start of middle school) and group differences in internalizing symptoms are examined concurrently and longitudinally. This approach adds to existing work by examining the early timing hypothesis across six waves of data and among an ethnically diverse sample of girls attending public middle schools in primarily low SES, urban neighborhoods. Not only can initial pubertal timing group differences in internalizing symptoms be examined, but also potential differences in the trajectories of internalizing symptoms across waves. Consistent with previous findings, it is hypothesized that girls classified as early maturing at the start of middle school will show higher levels of internalizing symptoms than will their on-time or late maturing peers and that these differences will remain stable or increase throughout the 3 years of middle school.

Next, all six waves of data are used to create a measure of pubertal timing that allows girls to change their relative standing in terms of pubertal development from one wave to the next. This approach is similar to that taken by Ge et al. (2003) in their seminal study of pubertal timing group changes across two waves; however, it builds on their work by relying on a full six waves of pubertal timing data collected across 3 years of middle school. Drawing on their findings, it is hypothesized that within-person changes in the direction of being relatively more developed than peers from one wave to the next will be associated with concurrent increases in internalizing symptoms. Finally, we investigate whether the link between pubertal timing and internalizing symptoms varies across study waves. For instance, when pubertal timing is measured in the fall of sixth grade—a time when early maturation is presumably highly noticeable—girls who are more developed might be at risk for internalizing symptoms, whereas relatively advanced development compared to peers in the spring of eighth grade—a time when most girls have started showing signs of puberty—might not be associated with psychological distress. Based on this reasoning, it is hypothesized that advancements in pubertal timing relative to peers will be related to internalizing symptoms at the start of middle school, but not at the end of middle school. It is also hypothesized that, while late maturation will not be associated with internalizing symptoms in the beginning of middle school, being later maturing relative to peers toward the end of middle school—when it’s most likely to stand out—will be linked to increased psychological distress.

Method

Participants

The participants in this study took part in a larger longitudinal study of peer relationships in middle school (Graham et al. 2003). Students were recruited from 6th grade classrooms across 11 public middle schools in the Los Angeles metropolitan area. The schools consisted primarily of students from low SES backgrounds, with student eligibility for free or reduced-price meal programs ranging from 39.5 to 86.7% across all schools. Data were collected each fall and spring of the three middle school years (i.e., 6th–8th grades), resulting in six waves. Participation rates across the six waves of the study ranged between 99% at the start of 6th grade to 75% at the end of 8th grade, a better retention rate than would be expected given average student mobility within the schools we studied (for further details, see Nylund et al. 2007). The sample for the current study includes 1,167 girls (mean age = 11.6 years) who participated in at least two waves of the study. A group of 64 girls from the original sample who did not provide a race/ethnicity (n = 26) or who identified their ethnic affiliation as “other” (n = 38) was deemed too small and too heterogeneous to include in the final analysis sample. Girls not included in the analysis sample did not differ from those in the analysis sample on age, pubertal timing, or internalizing symptoms measured at wave one. The self-reported racial/ethnic distribution of the analysis sample was 50% Latino, 30% Black/African American, 11% Asian, and 9% White.

Table 1 shows the number of girls who completed study measures at each wave. Analyses were conducted to examine the influence of non-participation on all study variables. Adolescents who did not participate in all six waves were more likely to be African American than were those participating at every wave, χ2 (1) = 50.91, p < .001. By including ethnicity in all models, the possibility of bias is reduced, allowing more appropriate generalization of results (Singer and Willett 2003). There were no significant differences between those who participated in all six waves and those with fewer data points on pubertal timing, global self-worth, depressive symptoms or social anxiety at each wave for which data were available.

Procedures

Students were recruited from homeroom classes in the fall of 6th grade. Seventy-eight percent of the students initially contacted returned signed parental consent forms, 91% of which granted permission to take part in the study. Students receiving parental consent were asked to provide written assent prior to participation. Fall data collection began after students had been in school for at least 2 months and spring data collection took place roughly in the middle of the spring academic semester. At each wave, measures in the current study, along with a collection of other measures not used here, were assembled in booklet form and were group administered by researchers during a single nonacademic class period. Teachers were not involved in the data collection procedures for the current study. All instructions and questionnaire items, aside from the items pertaining to pubertal development, were read aloud by a graduate researcher as students followed along and responded on their own to the questions. The pubertal development scale appeared approximately in the middle of the larger survey and, when the administrators reached the measure, they informed participants that the next set of questions was private and was to be completed individually. The graduate researchers then walked around the room and helped participants who had questions or appeared to have trouble with the measure. Once all students had completed the measure, the administrators resumed reading aloud the remainder of the survey items. Adolescents were given a small monetary award in gratitude for their participation at each wave.

Measures

Self-Perceived Pubertal Development

The Pubertal Development Scale (PDS; Petersen et al. 1988) allows participants to report on their growth in several areas specific to each gender. Girls reported on height, skin changes, breast development, and body hair. For each question, they indicated whether development had not yet started (1); barely started (2); definitely started, but is not finished (3); or seems completed (4). Girls also reported whether or not they had begun to menstruate (no = 1, yes = 4). Scores for the five items were averaged within individuals at each wave, resulting in a single index of pubertal development that maintained the original scale metric (1 = not started, 4 = completed). The PDS has well-established validity and reliability and is correlated with both parent and physician reports of pubertal development (Brooks-Gunn et al. 1987). The internal reliability of the pubertal development scale in the current study was stable across waves, with alphas ranging between .63 and .65.

To assess pubertal timing in the traditional manner, average PDS scores were standardized within school at the first wave of the study and those girls scoring greater than one standard deviation above the mean were categorized as early, those with scores more than one standard deviation below the mean were considered late, and the remainder of the girls were categorized as on-time maturing. This method of creating pubertal timing groups has been used in previous research (e.g., Haynie 2003); however, some researchers standardize pubertal timing within age group (e.g., Ge et al. 2007). We purposefully chose to standardize scores across all girls in the same school and grade level, rather than girls of the same age. Inasmuch as girls in the same grade are grouped into classes together, and thus spend a considerable amount of time in same-grade peer groups, we believe that grade-mates are likely a salient reference group in terms of self-perceptions. It should be noted, however, that trends reported here were all the same when pubertal timing was standardized within age and school. Finally, because the traditional approach views pubertal timing as a between-subjects variable, and because our statistical analyses required no missing data at the between-subjects level, girls who were missing wave one puberty data were assigned a pubertal timing classification based on whether they were early, on-time, or late maturing compared to other girls at wave 2 (n = 106) or wave 3 (n = 20).

To assess pubertal timing longitudinally as a time-varying measure, average PDS scores were standardized within school at each wave and were allowed to vary within girls over time. The resulting continuous pubertal development scores represented each girl’s maturational timing relative to other girls in her school at that particular wave. Girls with relatively more advanced development at any given wave, compared with their peers, can be considered relatively earlier maturing since the participants were closely age-spaced and because the time frame of the study was one in which pubertal development was just getting underway for a majority of the girls (see Table 1). The findings reported here were similar when dummy-coded variables comparing early, on-time, and late maturing girls were used to represent pubertal timing in the analyses.

To illustrate the dynamic nature of pubertal timing, Fig. 1 depicts individual pubertal development trajectories across middle school for four prototypical girls attending the same school. Mean scores on the Pubertal Development Scale (PDS; Petersen et al. 1988) are plotted for each of the four girls across the fall and spring semesters of the three middle school years. The average level of pubertal development reported by all girls in their grade is plotted at each wave, with the area within one standard deviation of that average highlighted. If a girl’s PDS score falls within the highlighted area, she would be considered “on-time” in maturation relative to peers. Girls whose PDS scores fall above or below the highlighted area would be categorized as “early” and “late” maturing, respectively. Within-person change in pubertal timing can be seen in Fig. 1 as the prototypical girls move in and out of the highlighted area across the duration of middle school. For example, when compared with peers, hypothetical “Girl B” would be categorized as on-time maturing throughout 6th grade, but she would then switch to being categorized as early maturing compared to peers in the fall of 7th grade and remain so throughout the rest of middle school. On the other hand, even though her actual physical development didn’t change, “Girl A” would be considered early maturing compared to her peers in sixth grade but on-time maturing in the fall of 7th grade. To further complicate matters, Girl A then moves back into early maturation territory in 8th grade. Indeed, even referring to a girl as “early”, “on-time”, or “late” maturing during middle school seems too static of a notion given these sorts of dynamic fluctuations.

Pubertal development trajectories across middle school, based on mean scores from the Pubertal Development Scale (PDS), are depicted for four prototypical girls attending the same school. The solid line represents the average level of pubertal development across all girls in the same grade at school, while the highlighted area identifies the range of scores falling within one standard deviation of average at each wave. Based on the traditional approach, girls whose PDS scores fall above, within, or below the highlighted area at a given wave would be considered “early”, “on-time” and “late” maturing at that wave, respectively

Global Self-Worth

The 6-item general self-perception subscale of the Self-Perceived Profile for Children (SPPC: Harter 1985) was used to measure global self-esteem. Students were presented with two statements separated by the word “but”, with each statement reflecting high or low global self-worth. Respondents choose one alternative and then decide whether it is “really true for me” or “sort of true for me”, which creates 4-point scales that are summed and averaged across items. This instrument is widely used in developmental research with adolescents and it has good psychometric properties. In the current study, alpha ranged between .80 and .89 across the six waves of data.

Depressive Symptoms

The Short Form of the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI: Kovacs 1992) was used to assess depressive affect. For each item, respondents were asked to choose one of three sentences that best described how they had been feeling during the past 2 weeks. For example, an adolescent would be presented with the following three sentences and asked to choose one: “I am sad once in awhile” (response coded as 0); “I am sad many times” (response coded as 1); and “I am sad all the time” (response coded as 2). Scores were then summed and averaged across items. The ten items with the strongest factor loadings from the original CDI (Kovacs 1985) comprise the Short Form. These items correlate well with the long version (r = .89 in Kovacs 1992) and they have good internal consistency (α ranged between 0.81 and 0.89 across waves in the current study).

Social Anxiety

Anxiety about negative evaluation from others was assessed utilizing five items from the Fear of Negative Evaluation subscale of the Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents (SAS-A: La Greca and Lopez 1998). Each item, such as, “I worry about what others think of me”, was rated on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all, 5 = all the time). In the current study, the scale had good internal consistency (α ranged from 0.82 to 0.88 across waves).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents the means and standard deviations for the study variables, separated by wave. At wave one—the beginning of sixth grade—the mean PDS score was 2.13 (SD = .63), indicating that girls reported, on average, that their development has just begun. This average score is similar to that reported by Ge et al. (2002, 2003) for African American fifth grade females. There were no significant ethnic group differences in average PDS scores across waves. Girls’ average reports of their pubertal development increased across middle school and, by the end of eighth grade, the average girl reported that her development had definitely started, but was not yet finished (M = 3.06, SD = .50).

The wave one pubertal timing groups were next examined. Girls who were classified as early maturing in the beginning of sixth grade reported that their development, on average, was underway, but had not yet finished (M = 3.14, SD = .25). Girls classified as on-time reported development that had barely started (M = 2.05, SD = .35) and late maturing girls, on average, reported not having started pubertal development (M = 1.32, SD = .15).

An examination of within-person change in pubertal timing indicated that, on average, 18% of the sample changed pubertal timing classification from one wave to the next. Pubertal timing classification remained the same across all six waves of data for only 168 girls (135 on-time, 20 late, and 13 early), indicating significant within-person variability in pubertal timing across waves. Few girls switched more than one timing group from one wave to the next. For example, while 45% of the early maturing girls and 53% of the late maturing girls switched to being on-time from wave one to wave two, only 1% of the girls categorized as early at wave one switched to being categorized as late at wave two and only 3% of the girls categorized as late at wave one switched to being early at wave two.

Others have suggested that individual differences in the duration or tempo of pubertal development might help account for such within-person shifts in pubertal timing (e.g., Ge et al. 2003). To explore the main tenet of this theory—that individual differences exist in the tempo of pubertal development—we examined a random effects growth model of pubertal development across the six waves of the study. A significant random effect of wave in predicting pubertal development (τ = .01, p < .001) suggests the existence of individual differences in the rate at which pubertal development progresses within girls over time.

Internalizing Symptoms

Table 2 presents bivariate correlations among internalizing symptom outcomes within each study wave. All correlations were significant in the expected direction at the p < .001 level. A series of multilevel modeling equations were assessed using the HLM program (Raudenbush et al. 2000) to model initial internalizing symptoms and symptom trajectories over the course of middle school. The first model fit for each outcome was the unconditional means model, characterized by the absence of predictors at every level. The intraclass correlation coefficient, which assesses the relative magnitude of between-person versus within-person variance, was calculated for each outcome. Slightly more than half of the total variation in self-worth (58%) and depressive symptoms (60%) is attributable to differences between adolescents. In terms of social anxiety, 41% of the total variation can be attributed to differences between adolescents and 59% is attributable to within-adolescent changes over time. The next model fit for each outcome was the unconditional growth model, which included time (i.e., wave) as the sole predictor, coded so that zero represented the first assessment point and the values one through five corresponded to each successive wave. Growth models that included curvilinear effects for wave were also examined. A quadratic rate of change term was significant for depressive symptoms (γ = .004, SE = .001, p < .01) and was, therefore, included in subsequent models pertaining to that outcome.

Traditional Pubertal Timing Model

Pubertal timing differences, based on reports from the beginning of sixth grade, were used to predict internalizing symptoms over time. Pubertal timing was dummy-coded such that the on-time group served as a comparison to the two off-time groups. Ethnicity was also added as a predictor in the form of three dummy coded variables comparing African American, Asian, and White girls, respectively, to Latina girls, who represent the largest proportion of our sample and were, therefore, considered the reference group. The final model for each of the three internalizing symptom outcomes is shown in Table 3.

Global Self-Worth

First, the pubertal timing variables were entered as predictors of the intercept and rate of change in global self-worth. The estimated initial self-worth for the average on-time maturing girl was 3.11 and the average difference in initial self-worth between on-time and early maturing girls was −0.12 (SE = .05, p < .05). Thus, being categorized as early maturing compared to on-time maturing at the first wave was associated with lower self-worth at the start of middle school. The average late maturing girl reported higher initial self-worth (γ = .12, SE = .04, p < .05) compared to the average on-time maturing girl. No significant differences between timing groups were evident for rate of change in self-worth; girls in all maturation groups appeared to remain stable in self-worth across the middle school years. African American girls (γ = .15, SE = .05, p < .01) and White girls (γ = .21, SE = .07, p < .01) reported higher levels of self-worth than did Latinas at the start of middle school. In terms of change trajectories, Asian girls decreased significantly in self-worth over time (γ = −.04, SE = .02, p < .05) compared to Latinas, whose reports of self-worth did not change across waves (γ = .01, SE = .01, ns). Interactions between ethnicity and pubertal timing groups were tested as predictors of initial status and rate of change in self-worth and no significant findings emerged. With the addition of pubertal timing at level 2, between-person residual variance was reduced by 1.3%, which corresponds to an effect size r of .11.

Depressive Symptoms

Being classified as early maturing compared to peers at wave one was also associated with higher initial reports of depressive symptoms. The estimated initial level of depressive symptoms for the average on-time maturing girl was 0.33 (SE = .01) and the average difference in initial depression between on-time and early maturing girls was 0.06 (SE = .03, p < .05). Thus, being identified as early maturing compared to on-time maturing was associated with higher depressive symptoms at the start of middle school. Late maturing girls, on the other hand, reported lower initial depressive symptoms (γ = −.06, SE = .02, p < .01) compared to on-time maturing girls. No significant differences between timing groups were evident for linear or quadratic rates of change in depressive symptoms. Results also indicated that African American girls (γ = −.06, SE = .02, p < .01) and white girls (γ = −.06, SE = .03, p < .05) reported lower levels of depressive symptoms than did Latina girls at the start of middle school. No ethnic group differences were evident in the prediction of linear or quadratic change. Additional analyses revealed no significant ethnicity by pubertal timing group interactions in the prediction of initial status or rate of change in depressive symptoms. With the addition of pubertal timing at level 2, between-person residual variance was reduced by 1.5%, which corresponds to an effect size r of .12.

Social Anxiety

Pubertal timing did not significantly predict initial status or rate of change in social anxiety. As shown in Table 3, the results indicated that African American girls reported lower social anxiety than did Latina girls at the start of middle school (γ = −.23, SE = .06, p < .001). Asian girls, on the other hand, reported higher social anxiety than did Latina girls (γ = .22, SE = .08, p < .01). Both Asian and white girls showed a slower decrease in social anxiety over time than did Latina girls (γ = .05, SE = .02, p < .01; γ = .07, SE = .02, p < .01, respectively).

Summary

The traditional pubertal timing approach examined whether pubertal timing classifications made at the beginning of sixth grade were associated with levels of internalizing symptoms at the start of middle school and changes in internalizing symptoms across the middle school years. Results indicated that girls classified as early maturing at the beginning of sixth grade showed lower self-worth and higher depressive symptoms at that same wave than did on-time and late maturing girls. Change trajectories of internalizing symptoms over the course of middle school did not differ according to pubertal timing group. Thus, girls classed as early maturing in the fall of sixth grade were estimated to be lower on global self-worth and higher on depressive symptoms compared to their peers across all of the middle school years. Pubertal timing classifications made in the fall of sixth grade were not associated with initial levels of, nor trajectory differences in, social anxiety. Although there were ethnic group differences in depressive symptoms, global self-worth, and social anxiety overall, the associations between pubertal timing and internalizing symptoms did not differ significantly by ethnic group. Finally, as shown at the bottom of Table 3, significant variance remained in the outcomes after taking into account pubertal timing and ethnicity, indicating that additional between-person predictors could help explain individual differences in initial internalizing symptoms and change trajectories across middle school.

Pubertal Timing as a Time-Varying Predictor

In this approach, pubertal timing—in the form of average PDS scores standardized within school at each wave—was allowed to vary within individuals over time. Including pubertal timing as a time-varying predictor assesses the hypothesis that girls will report increases in internalizing symptoms at waves in which they report relatively more advanced pubertal development compared to peers. In addition, an interaction term was added to these models to examine whether the association between the time-varying pubertal timing predictor and internalizing symptoms depends on wave. Potential ethnic differences in the association between the predictors and internalizing symptoms were also examined.

Global Self-Worth

As can be seen in the left column of Table 4, pubertal timing was a significant predictor of global self-worth (γ = −.05, SE = .02, p < .01). A one-unit increase in pubertal timing is associated with a .05 unit drop, on average, in self-worth. Since pubertal timing is a standardized variable with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one, a one-unit increase in pubertal timing roughly corresponds to the typical cut-off point for being classified as early maturing. Thus, on average, girls reported decreased self-worth at waves in which they reported relatively more advanced development compared to peers. To examine whether this association varies by wave, a pubertal timing by wave interaction term was added to the model. As can be seen in Table 4, the interaction term was significant (γ = .01, SE = .005, p < .05).

The online interactive calculator for probing interactions developed by Preacher et al. (2006) was used to statistically examine the relationship between self-worth and pubertal timing at the start of middle school and at the end of middle school. At the start of middle school (wave 1), the simple slope was −.051 (z = −3.35, p < .001), indicating that earlier pubertal timing was related to lower self-worth. In contrast, at the end of middle school (wave 6), the simple slope was −.003 (z = −.20, ns), indicating that pubertal timing and self-worth were not associated (see upper panel of Fig. 2). Only toward the beginning of middle school, therefore, did girls report significant decreases in self-worth at waves in which they reported increases in pubertal timing relative to peers. By the end of middle school, relative differences in pubertal development compared to peers were not related to shifts in self-worth. An examination of the region of significance suggested that, on average, earlier pubertal timing was related to lowered self-worth only before the spring of 7th grade. With the addition of pubertal timing and the pubertal timing by wave interaction term at level 1, within-person residual variance in global self-worth was reduced by 2.8%, which corresponds to an effect size r of .17.

To illustrate significant within-person interactions, global self-worth and social anxiety are depicted as a function of pubertal timing at each study wave. Standardized PDS scores ranging between 1 (earlier developing) and −1 (later developing) are shown on the x-axes and lines represent predicted values of global self-worth (upper panel) and social anxiety (lower panel) associated with the range of pubertal timing scores at each study wave

Depressive Symptoms

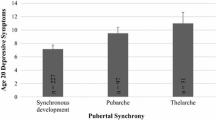

As can be seen in the middle column of Table 4, pubertal timing was a significant predictor of depressive symptoms (γ = .02, SE = .007, p < .05), with a one-unit increase in pubertal timing associated with a .02 unit increase in depressive symptoms. Thus, girls reported higher depressive symptoms at waves in which they reported more advanced development compared to peers. The association between pubertal timing and depressive symptoms did not vary by wave (γ = −.003, SE = .002, ns). Further analyses also revealed that the association between pubertal timing and depressive symptoms did not vary as a function of ethnic group, nor as a function of quadratic rate of change. Adding pubertal timing at level 1 reduced within-person residual variance in depressive symptoms by 2.4%, which corresponds to an effect size r of .16.

Social Anxiety

Pubertal timing itself was not a significant predictor of social anxiety, but, as can be seen in the right column of Table 4, the pubertal timing by wave interaction term was significant, (γ = −.01, SE = .006, p < .05). In order to further examine the interaction, the simple slopes were calculated for the relationship between social anxiety and timing at wave one and at wave six (Preacher et al. 2006). At the start of middle school (wave 1) the simple slope was .03 (z = 1.59, ns) and, by the end of middle school (wave 6), the simple slope was −.04 (z = 1.74, p < .10). Thus, although reports of social anxiety were not associated with pubertal timing toward the beginning of middle school, social anxiety tended to increase when girls reported less advanced pubertal maturation relative to peers toward the end of middle school (see lower panel of Fig. 2). An examination of the region of significance suggested that less advanced pubertal timing compared to peers would be expected to significantly predict higher social anxiety if both were measured at the beginning of high school. With the addition of pubertal timing and the pubertal timing by wave interaction term at level 1, within-person residual variance in social anxiety was reduced by 3.8%, which corresponds to an effect size r of .19.

Summary

The dynamic approach allowed pubertal timing to vary within adolescents across the middle school years. The main effect of the time-varying pubertal timing predictor on depressive symptoms indicated that, on average, girls reported increases in depressive symptoms at waves in which they reported more advanced maturation relative to other girls in their grade. Results also indicated that pubertal timing and wave interacted in the prediction of both global self-worth and social anxiety. Within-person changes in the direction of more advanced pubertal maturation relative to peers from one wave to the next predicted decreases in self-worth only at the start of middle school. By the end of middle school, reports of self-worth did not change as a function of pubertal timing. On the other hand, within-person changes in pubertal timing relative to peers were not associated with social anxiety toward the beginning of middle school, but more advanced maturation relative to peers tended to predict decreases in social anxiety toward the end of middle school. Thus, it was less advanced maturation relative to peers that was associated with increased social anxiety at the end of middle school. Neither the main effects of pubertal timing nor the interactions between pubertal timing and wave differed across ethnic groups.

Discussion

Foundational work linking early pubertal timing and mental health among girls focused almost exclusively on white, middle class adolescents. Moreover, research on this topic has rarely included more than one measurement of pubertal development. The current study contributes to the extant research by testing the early timing model among a population underrepresented in the literature and by taking a dynamic approach to the measurement of pubertal timing. Across six waves of data, collected during a developmental period in which most girls were in the midst of puberty, we assessed pubertal timing relative to peers at each wave and modeled the resulting time-varying measure as a predictor of depressive symptoms, social anxiety, and global self-worth. Findings suggested substantial within-person variability in pubertal timing from one wave to the next, which highlights not only the dynamic nature of pubertal development but also the variable associations between off-time maturation and emotional adjustment.

A main effect of pubertal timing on depressive symptoms indicated that girls who were relatively more developed compared to peers at any given wave were at risk for higher depressive symptoms at that same wave, regardless of whether or not they were earlier maturing at other waves. These findings are consistent with previous research supporting the early timing model; however, they provide a more nuanced and complex view of what it means to be early maturing and how this classification relates to concurrent reports of internalizing symptoms. Girls reported increases in depressive symptoms at waves in which they were relatively more advanced in physical maturation compared to other girls in their grade, even if they were not considered more developed than most of their peers at prior waves.

The significant interaction between pubertal timing and wave in the prediction of both global self-worth and social anxiety further illustrates the complexity of the association between pubertal development and internalizing symptoms. While being more developed compared to peers at any given wave was consistently associated with greater reports of depressive symptoms, the effect of relative pubertal timing on self-worth and social anxiety differed depending on measurement occasion. At the start of middle school, girls reported decreases in self-worth at waves in which they were more advanced maturing relative to peers; however, by the end of middle school, relative pubertal maturation was not associated with shifts in self-worth. This suggests that the risk for low self-worth associated with being relatively more developed than peers is most pronounced early on, when advanced maturation is most noticeable. Although within-person fluctuations in pubertal timing were associated with changes in self-worth only toward the beginning of middle school, it is certainly possible that some girls started puberty early, continued to develop earlier than most of their peers, and consistently reported lower self-worth across the middle school years. In fact, both of these scenarios are consistent with the idea that early maturation is especially risky when it’s evident in early adolescence. That is, when most girls are just beginning the pubertal process, being more developed might be particularly conspicuous and troublesome.

On the other hand, being relatively late maturing is most noticeable later on in middle school, when most girls are well on their way to pubertal maturation. The significant interaction between pubertal timing and wave in the prediction of social anxiety is consistent with this claim. Pubertal maturation relative to peers at initial waves of the study was not associated with shifts in social anxiety; yet, by the end of middle school, girls tended to report increases in social anxiety when their pubertal development became relatively less advanced compared to peers. Thus, results suggest that the link between pubertal timing and internalizing symptoms varies across the types of internalizing problems assessed and depends on the time point at which these associations are examined.

Results based on the traditional model indicated that girls classified as early maturing at the beginning of the study showed lower self-worth and higher depressive symptoms than did on-time and late maturing girls. These findings were consistent across ethnic groups, providing support for the early timing model among an ethnically diverse sample of girls attending public middle schools in an urban environment. This corroborates previous findings that early maturation is associated with depressive symptoms among rural and suburban African American girls (Ge et al. 2003) and urban African American and Latina girls (Nadeem and Graham 2005; Reynolds and Juvonen 2011). The current study builds on this research by examining depressive symptoms across a longer time-span (and more waves) and by also including assessments of global self-worth and social anxiety. Although early maturation was associated with depression and low self-worth, social anxiety did not differ by pubertal timing group when timing classifications were made at the beginning of the study, a finding that was reflected in the dynamic approach.

The slightly different trends evident for each of the three internalizing outcomes suggest that relative pubertal maturation brings about greater vulnerability in certain domains of adjustment than in others and this is particularly true at “risky” points in time. The reasons for these specific associations should be the topic of future research, particularly with regards to self-worth and social anxiety, which have received much less attention in the literature than have symptoms of depression. At this point, we can only speculate about the meaning behind the different patterns of results for each outcome. For instance, since all of our participants were drawn from traditional middle schools (i.e., 6th–8th grades), it could be the case that earlier maturing girls were particularly vulnerable to low self-worth when experiencing the simultaneous transitions of pubertal development and middle school entry. This idea is consistent with work suggesting that girls who experience early puberty at the same time that they experience the transition to junior high school and also commence dating tend to show particularly low self-esteem (Simmons et al. 1979).

On the other hand, most adolescents tend to experience at least some vulnerability to anxiety during the transition to middle school, which typically fades as they move from the position of being the youngest to the oldest students at school (Benner and Graham 2009; Hirsch and Rapkin 1987). If social anxiety is common at the start of middle school and if it is related to feeling and/or appearing less mature than older schoolmates, then might the advantages of looking older help compensate for the vulnerability associated with early maturation among girls? By the end of middle school, however, it could be that late maturing girls are vulnerable to social anxiety because they likely stand out in comparison to older-looking peers. One particularly intriguing avenue for future research is to examine the link between pubertal timing and various indicators of mental health among a sample of girls attending combined elementary and junior high schools (K—8).

Limitations and Future Directions

The current study contributed to the extant literature in three notable ways. First, it extended generalizability of the early pubertal timing model to a large, ethnically diverse sample of adolescent girls from an urban environment. Next, it took a novel approach to modeling internalizing symptoms as a function of within-person variability in pubertal timing. Finally, it examined the connection between pubertal timing and internalizing symptoms across six waves of data collected when most girls were in the midst of pubertal development. As such, the current study addressed a number of methodological gaps in existing research linking early pubertal timing with internalized distress among adolescent girls.

Despite its contributions to the literature, the current study has limitations that should be kept in mind when interpreting its results and designing future research. The current study focused on pubertal timing among girls because previous research has suggested that it is an important factor contributing to their psychological well-being; however, many studies have shown that early maturational timing might also be detrimental to boys (e.g., Ge et al. 2006b; Jin et al. 2008). In addition, pubertal timing classifications have been observed to change from one assessment period to the next among boys (Ge et al. 2003). Thus, future longitudinal studies would not only benefit from utilizing more than two waves of data, but also from an inclusion of both female and male adolescents. In designing such studies, the differences in onset of pubertal development between sexes should be taken into consideration and assessments should span a time period wide enough to capture key pubertal changes among both girls and boys.

As in most research on pubertal development, all of the measures of internalizing symptoms and pubertal development in the current study were based on self-report. Future research should address concerns about shared method variance by including reports from doctors, parents, or teachers, and particularly in regards to pubertal timing. If physical examination by a trained professional is impractical, teachers seem to be well-suited to evaluate relative pubertal timing since they can presumably make judgments in terms of outward indicators of pubertal maturation. This would be particularly advantageous if the social conspicuousness of pubertal development is important in predicting internalizing symptoms.

It should be noted that pubertal status, pubertal timing, and chronological age are confounded in research conducted with adolescents during the pubertal transition. When pubertal status is measured in samples of participants that vary considerably in age, for example, its effects are difficult to interpret because they might be attributed to pubertal development, chronological age, or a combination of the two. Many investigators have attempted to address this issue by measuring pubertal status among adolescents who are closely spaced in age; however, such an approach can conflate pubertal status and pubertal timing. The current study began during early adolescence and its sample consisted of girls similar in age; thus, advanced pubertal status largely reflects earlier pubertal timing. Further research is necessary to disentangle the effects of status versus timing.

While pubertal timing in the current study was based on average scores on the Pubertal Development Scale (PDS; Petersen et al. 1988), future research should further examine self-perceptions of pubertal timing by directly asking adolescents if they are developing early, on-time, or late compared to most of their peers. This would be particularly useful if feelings of being “different” from peers in terms of maturation contribute to psychological maladjustment. Including measures of both self-perceived pubertal timing and self-reported pubertal status in a single study could provide insight into the meaning associated with PDS scores. For example, researchers could investigate whether girls classified as early maturing based on average PDS scores also perceive themselves to be maturing earlier than peers, and whether discrepancies across self-views and other classifications relate to psychosocial adjustment.

Finally, it should be noted that the effects observed in the current study were small. The associations described here are undoubtedly complex, with many factors contributing to both between- and within-person variance in the outcomes. It should be noted, however, that even small effects can provide important contributions to scientific knowledge (see Rosenthal 1994) and can have a significant impact on social policy or in other applied contexts (McCartney and Rosenthal 2000). Nonetheless, further research is needed to verify the current findings, particularly with regards to interactions between wave and within-person changes in pubertal timing in models of global self-worth and social anxiety, as the current study is the first to our knowledge that has tested such effects.

Conclusion

While the current study adds to a growing body of literature supporting the early timing model, it also highlights the complexity of the association between pubertal timing and internalizing symptoms as girls navigate the pubertal transition. The traditional approach to assessing pubertal timing provided important information regarding the psychological adjustment of our urban, ethnically diverse sample of adolescent girls, suggesting that earlier pubertal development at the start of middle school is a risk factor for depressive symptoms and low self-worth throughout the middle school years regardless of ethnic group affiliation. The dynamic approach, on the other hand, provided a more complex and nuanced view of this association as it played out within individual girls across the middle school years. Although earlier maturation, particularly when assessed earlier on, is associated with internalizing symptoms, it also appears that pubertal timing is not always consistent within individuals across development and that internalizing symptoms might be temporarily experienced if, at that particular time in development, an individual is different from peers in terms of maturation. Adding another layer of complexity, the current findings suggest that within-person fluctuations in relative pubertal maturation might be associated with changes in emotional distress only at particularly vulnerable points in development. Based on the results reported here, it is clear that many important questions remain unanswered in the study of pubertal timing and emotional distress and, consequently, there exist many new and intriguing avenues for future research.

References

Benner, A. D., & Graham, S. (2009). The transition to high school as a developmental process among multiethnic urban youth. Child Development, 80(2), 356–376.

Brooks-Gunn, J., Warren, M. P., Rosso, J., & Gargiulo, J. (1987). Validity of self-report measures of girls’ pubertal status. Child Development, 58(3), 829–841.

Carter, R., Caldwell, C., Matusko, N., Antonucci, T., & Jackson, J. (2010). Ethnicity, perceived pubertal timing, externalizing behaviors, and depressive symptoms among black adolescent girls. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. doi:10.1007/s10964-010-9611-9.

Carter, R., Jaccard, J., Silverman, W. K., & Pina, A. A. (2009). Pubertal timing and its link to behavioral and emotional problems among `at-risk’ African American adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescence, 32(3), 467–481.

Dick, D. M., Rose, R. J., Viken, R. J., & Kaprio, J. (2000). Pubertal timing and substance use: associations between and within families across late adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 36(2), 180–189.

Ge, X., Brody, G. H., Conger, R. D., & Simons, R. L. (2006a). Pubertal maturation and African American children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35(4), 528–537.

Ge, X., Brody, G. H., Conger, R. D., Simons, R. L., & Murry, V. M. (2002). Contextual amplification of pubertal transition effects on deviant peer affiliation and externalizing behavior among African American children. Developmental Psychology, 38(1), 42–54.

Ge, X., Conger, R. D., & Elder, G. H., Jr. (2001). Pubertal transition, stressful life events, and the emergence of gender differences in adolescent depressive symptoms. Developmental Psychology, 37(3), 404–417.

Ge, X., Kim, I. J., Brody, G. H., Conger, R. D., Simons, R. L., Gibbons, F. X., et al. (2003). It’s about timing and change: pubertal transition effects on symptoms of major depression among African American youths. Developmental Psychology, 39(3), 430–439.

Ge, X., Natsuaki, M. N., & Conger, R. D. (2006b). Trajectories of depressive symptoms and stressful life events among male and female adolescents in divorced and nondivorced families. Development and Psychopathology, 18(1), 253–273.

Ge, X., Natsuaki, M. N., Neiderhiser, J. M., & Reiss, D. (2007). Genetic and environmental influences on pubertal timing: Results from two national sibling studies. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 17(4), 767–788.

Graber, J. A., Lewinsohn, P. M., Seeley, J. R., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (1997). Is psychopathology associated with the timing of pubertal development? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(12), 1768–1776.

Graber, J. A., Seeley, J. R., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Lewinsohn, P. M. (2004). Is pubertal timing associated with psychopathology in young adulthood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(6), 718–726.

Graham, S., Bellmore, A., & Juvonen, J. (2003). Peer victimization in middle school: When self-and peer views diverge. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 19(2), 117–137.

Harter, S. (1985). Manual for the self-perception profile for children. Denver, CO: University of Denver.

Haynie, D. L. (2003). Contexts of risk? Explaining the link between girls’ pubertal development and their delinquency involvement. Social Forces, 82(1), 355–397.

Hayward, C., Gotlib, I. H., Schraedley, P. K., & Litt, I. F. (1999). Ethnic differences in the association between pubertal status and symptoms of depression in adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescent Health, 25(2), 143–149.

Hayward, C., Killen, J. D., Wilson, D. M., Hammer, L. D., Litt, I. F., Kraemer, H. C., et al. (1997). Psychiatric risk associated with early puberty in adolescent girls. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(2), 255–262.

Hirsch, B. J., & Rapkin, B. D. (1987). The transition to junior high school: A longitudinal study of self-esteem, psychological symptomatology, school life, and social support. Child Development, 58(5), 1235–1243.

Jin, R., Ge, X., Brody, G., Simons, R., Cutrona, C., & Gibbons, F. (2008). Antecedents and consequences of psychiatric disorders in African-American adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37(5), 493–505.

Kovacs, M. (1985). The children’s depression inventory (CDI). Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 21(4), 995–998.

Kovacs, M. (1992). Children’s depression inventory: Manual. New York: Multi-Health Systems.

La Greca, A. M., & Lopez, N. (1998). Social anxiety among adolescents: Linkages with peer relations and friendships. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 26(2), 83–94.

Lynne, S. D., Graber, J. A., Nichols, T. R., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Botvin, G. J. (2007). Links between pubertal timing, peer influences, and externalizing behaviors among urban students followed through middle school. Journal of Adolescent Health, 40(2), 181.e7–181.e13.

McCartney, K., & Rosenthal, R. (2000). Effect size, practical importance, and social policy for children. Child Development, 71(1), 173–180.

Mendle, J., Turkheimer, E., & Emery, R. E. (2007). Detrimental psychological outcomes associated with early pubertal timing in adolescent girls. Developmental Review, 27(2), 151–171.

Nadeem, E., & Graham, S. (2005). Early puberty, peer victimization, and internalizing symptoms in ethnic minority adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 25(2), 197–222.

Nylund, K., Bellmore, A., Nishina, A., & Graham, S. (2007). Subtypes, severity, and structural stability of peer victimization: What does latent class analysis say? Child Development, 78(6), 1706–1722.

Obeidallah, D., Brennan, R. T., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Earls, F. (2004). Links between pubertal timing and neighborhood contexts: Implications for girls’ violent behavior. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(12), 1460–1468.

Petersen, A., Crockett, L. J., Richards, M., & Boxer, A. (1988). A self-report measure of pubertal status: Reliability, validity, and initial norms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 17, 117–133.

Preacher, K. J., Curran, P. J., & Bauer, D. J. (2006). Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 31(4), 437–448.

Raudenbush, S. W., Bryk, A. S., Cheong, Y. F., & Congdon, R. (2000). HLM5: Hierarchical linear and nonlinear modeling (2000th ed.). Chicago: Scientific Software.

Reardon, L. E., Leen-Feldner, E. W., & Hayward, C. (2009). A critical review of the empirical literature on the relation between anxiety and puberty. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(1), 1–23.

Reynolds, B., & Juvonen, J. (2011). The role of early maturation, perceived popularity, and rumors in the emergence of internalizing symptoms among adolescent girls. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. doi:10.1007/s10964-010-9619-1.

Rosenthal, R. (1994). Parametric measures of effect size. In H. Cooper & L. V. Hedges (Eds.), The handbook of research synthesis (pp. 231–244). New York: Russel Sage Foundation.

Siegel, J. M., Yancey, A. K., Aneshensel, C. S., & Schuler, R. (1999). Body image, perceived pubertal timing, and adolescent mental health. Journal of Adolescent Health, 25(2), 155–165.

Simmons, R. G., Blyth, D. A., Van Cleave, E. F., & Bush, D. M. (1979). Entry into early adolescence: The impact of school structure, puberty, and early dating on self-esteem. American Sociological Review, 44(6), 948–967.

Singer, J. D., & Willett, J. B. (2003). Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Susman, E. J., & Dorn, L. D. (2009). Puberty: Its role in development. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (3rd ed.). Hoboken: Wiley.

Zehr, J. L., Culbert, K. M., Sisk, C. L., & Klump, K. L. (2007). An association of early puberty with disordered eating and anxiety in a population of undergraduate women and men. Hormones and Behavior, 52(4), 427–435.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by grants from the National Science Foundation (BCS-9911525) and the William T. Grant Foundation (99100463) awarded to Sandra Graham and Jaana Juvonen and a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (NRSA) to Bridget Reynolds (F31 MH074244). We thank Drs. Sandra Graham, Rena Repetti, Andrew Fuligni, and Ted Robles for their comments and advice on earlier drafts of this paper. We would also like to thank Mike Robinson, the Peer Project, and the Relationships and Health Lab for their invaluable feedback and support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Reynolds, B.M., Juvonen, J. Pubertal Timing Fluctuations across Middle School: Implications for Girls’ Psychological Health. J Youth Adolescence 41, 677–690 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-011-9687-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-011-9687-x