Abstract

This study investigated age- and gender-specific associations between parental support and parental knowledge of the child’s whereabouts, on the one hand, and sexual experience and sexual health (the ability to have safe and pleasurable sexual experiences) on the other hand. A representative Dutch sample of 1,263 males and 1,353 females (aged 12–25 years), who had previously engaged in sexual intercourse, completed a questionnaire that included measures of these constructs. Both parental support and knowledge were positively associated with contraceptive use, social skills in sexual interactions, sexual satisfaction, and delay of sexual debut. Findings also revealed that the majority of correlations between parental support and sexual experience and sexual health are attributable to the relationship between a supportive family environment and parental knowledge of the child’s whereabouts. Parental knowledge thus appeared to be more important for healthy sexual development than parental support.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Adolescence can be characterized as a period of growth and development, particularly in the area of sexuality. Although sexual development is a lifelong process, there is no other life stage where it is more striking. In the Netherlands, most individuals have their first relational and sexual experiences during this life stage (De Graaf et al. 2005). Ideally, these experiences are safe and pleasurable for both partners. Positive sexual experiences are associated with general well-being, and thereby contribute to public health more generally (Whipple 2007). However, sex also entails risks of unintended pregnancy, sexually transmitted infection (STIs), and sexual coercion. The emotional, medical, and financial costs of these risks highlight the importance of studying sexual development.

Parents are considered to play a major role in sexual development. A large number of studies report associations between aspects of parenting and sexual (health) behavior during adolescence. The vast majority of these studies focus on one of two aspects of parenting, namely support or monitoring. Support is one of the two dimensions in the theoretical model on parenting styles proposed by Maccoby and Martin (1983). It encompasses aspects such as warmth, responsiveness, and child-centeredness. Monitoring is usually measured as the parents’ knowledge of their child’s whereabouts. Active supervision, however, is neither a prerequisite nor a guarantee for this knowledge. According to Stattin and Kerr (2000), parental knowledge is more often the result of spontaneous disclosure of the child than of active parental supervision. “Monitoring” thus seems to be a misleading term to describe this concept. We will, therefore, use the term “parental knowledge” instead. Parental knowledge becomes more and more important during adolescence, when children spend increasing amounts of time without direct parental supervision and leave parents to rely on what their children tell them (Kerr et al. 1999; Soenens et al. 2006).

It is evident that parental support and knowledge are not independent constructs. Children growing up in a loving and supportive family have more positive feelings about their parents, and are therefore more inclined toward self-disclosure (Kerr et al. 2003; Soenens et al. 2006). In turn, parents who know more about their children’s whereabouts are more trusting towards their children and react positively to the information that children share (Kerr et al. 1999, 2003). Until now, no study has tried to disentangle the relative contribution of parental support and knowledge in predicting sexual development. In order to guide parental behavior, it is important to know which parenting variable is most strongly related to sexual behavior and sexual health. If support is most important, the recommendations for parents are straightforward: they should focus on providing warmth and support in their families. If knowledge of the child’s whereabouts is most important, parents should be informed about which parenting strategies result in the highest levels of parental knowledge. Presumably, a warm family climate that enhances self-disclosure is an important part of this, but other means to gain this knowledge are also conceivable (Soenens et al. 2006).

Parenting and Sexual (Health) Behavior

Empirical research shows that both parental support and knowledge, in general, are linked to a delay of sexual debut and to having safe and pleasurable sexual experiences. Both parenting dimensions correlate with a later age of first intercourse (Bates et al. 2003; Bersamin et al. 2008; Hope and Chapple 2005; Johnson and Tyler 2007; Pedersen et al. 2003). Furthermore, high levels of parental support and knowledge are associated with more consistent contraceptive use (Coley et al. 2008; De Graaf et al. 2005; Dittus and Jaccard 2000), condom use (Borawski et al. 2003; Crosby et al. 2002a; Huebner and Howell 2003), a lower risk for STIs (Crosby et al. 2002b), the ability to refuse unwanted sex (Sionéan et al. 2002), communication skills with regard to contraception (Stone and Ingham 2002), and higher levels of sexual satisfaction (De Graaf et al. 2005; Ojanlatva et al. 2003). These findings suggest that parents play an important role in healthy sexual development.

Although there is abundant research on associations between parental support and knowledge, on the one hand, and sexual experiences of adolescents, on the other hand, important information is still missing. In particular, the large majority of research focuses on the age of first sexual intercourse, and measures of sexual health are usually restricted to protection against STIs or unwanted pregnancy. No studies have investigated associations between parental support and knowledge and the child’s sexual satisfaction and/or social skills in sexual interactions (for example, the ability to communicate sexual likes and dislikes, the ability to steer sexual interactions, or feeling self-confident in sexual interactions) in a large representative sample. While it is preferable that adolescents postpone sexual debut, in terms of social norms and outcomes for sexual health, it is also important that youths have safe and pleasurable sexual experiences when they eventually do become sexually active. Positive sexual experiences contribute to general personal well-being (Hull 2008; Whipple 2007), while experiences with pregnancy, STIs, or sexual coercion can have long-lasting negative consequences. Adequate social skills in sexual interactions are essential for arranging sexual encounters in a mutually rewarding way (Vanwesenbeeck et al. 1999). Earlier research has demonstrated the positive relationship between parental support and social skills (Barber 1997; Engels et al. 2002). The association between parental knowledge and adolescents’ self-disclosure also suggests an association with communication skills (Kerr et al. 2003). It is possible that the positive relationship between parental support/knowledge and social skills extends to social skills in sexual interactions.

Associations between parental support and adolescents’ age at first sexual intercourse appear to be stronger for girls, compared to boys (Davis and Friel 2001; McNeely et al. 2002; Rose et al. 2005). In addition, as children get older, links between parental support and adolescents’ experience with sexual intercourse seem to weaken (Lammers et al. 2000). In previous studies, stronger associations with parenting were also found for girls on other areas of adjustment, such as emotional problems (Helsen et al. 2000) or drinking (Rose et al. 2001). Previous research found decreasing links with age regarding parental support and emotional adjustment (Meeus et al. 2005) and delinquency as well (Meeus et al. 2004). Parental support and knowledge are, in general, higher for girls (Soenens et al. 2006; Stattin and Kerr 2000) and early adolescents (Meeus et al. 2005). As children age, however, friends and romantic partners become more important, in lieu of parents as sources of support (Furman et al. 2007). It is possible that the effect of parenting is more salient for girls and younger adolescents, because low levels of support and knowledge go more strongly against the norm for these groups.

Goals and Hypotheses of the Present Study

As described above, having safe and pleasurable sexual experiences is closely related to well-being, and social competence in sexual interactions is important for healthy psychosexual development. In spite of this, empirical tests of associations between parenting and youths’ sexual self-efficacy and satisfaction from representative national samples are very scarce. Our first goal is, therefore, to describe associations between parental support and knowledge of the child’s whereabouts and a broad range of sexual health aspects, including age of first sexual intercourse, number of sex partners, protection against STIs and unwanted pregnancy, social skills in sexual interactions, and sexual satisfaction. Following the evidence described above, we expect to find associations between higher levels of support and knowledge and a delay of first sexual intercourse, less sexual partners, consistent protective behavior and better social skills in sexual interactions.

In addition, our second goal is to explore whether the associations between parental support and knowledge, on the one hand, and sexual debut, safe sex behavior, social skills in sexual interactions, and sexual satisfaction, on the other hand, are age- and gender-specific. We expect the associations between parental support and sexual behavior and sexual health to be stronger for girls, compared to boys, in line with what was found in earlier research on parental support and experience with sexual intercourse (Davis and Friel 2001; McNeely et al. 2002; Rose et al. 2005). With regard to age specificity, results could be expected in one of two different directions. On the one hand, we could expect decreasing links with age, as is generally found in studies on relationships between parenting and sexual experience or other developmental areas. The exclusion of sexually abstinent adolescents from our sample, however, could also lead us to expect an absence of any age-specific links. Sexually experienced adolescents report less parental support and knowledge than their inexperienced peers (De Graaf et al. 2005). Their sexual status is probably accompanied by a certain degree of independence from parents. Associations with parental support and knowledge could, therefore, be approximately equal across age groups in this specific sample.

Our third goal is to investigate the relative contributions of parental support and knowledge in predicting sexual development. As described above, parental support and knowledge are correlated, and both of these concepts associate with sexual behavior and sexual health. These associations suggest that two alternative, mediational models are possible. The first model hypothesizes that knowledge of the child’s whereabouts increases with higher levels of parental support, and that this parental knowledge subsequently holds the most proximal links with sexual development. The second model hypothesizes that it is parental support, which is higher when children self-disclose more often, that holds the most important associations with sexual behavior and sexual health. We will examine both of these hypothetical models.

Method

Participants

Participants initially took part in “Sex under the age of 25”, a representative study of sexual behavior and sexual health of 12–25 year-olds in the Netherlands (N = 4,820). This study was reviewed and approved by the review board of the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMW). Sexual (health) variables were only measured among participants who had experienced sexual intercourse. Because the purpose of the present study was to investigate associations with these measures, participants who had not yet had intercourse were excluded from the analyses (N = 2,235).

This selection resulted in the inclusion of 1,273 males and 1,360 females, ranging in age from 12 to 25 years (M = 20.45 years, SD = 2.79). Limiting the sample to participants who had experienced intercourse resulted in an uneven distribution of participants among age groups. Specifically, the sample was composed of 295 (11.2%) 12–16 year-olds, 1,124 (42.7%) 17–20 year-olds, and 1,214 (46.1%) 21–24 year-olds. The sample was comprised of 81.1% native Dutch participants, 7.1% Western immigrants, and 11.8% non-Western immigrants.

Measures

The questionnaire began with questions about demographics, followed by measures of parental support, knowledge, sexual behavior, protection against pregnancy and STIs, social skills in sexual interactions, and sexual satisfaction. We calculated mean scores for each multi-item scale.

Parental Support and Knowledge

Measures of parental support and knowledge were selected from a questionnaire used in a large study on parenting in the Netherlands (Rispens et al. 1996). Participants’ perceptions of parental support were assessed by measuring parental affection (viz., “My parent lets me know that she/he loves me”) and responsiveness (viz., “My parent helps me well when I’m having a difficult time”). Participants were requested to indicate how much they agreed with these items on a four-point scale (1 = totally disagree, 4 = totally agree). To assess knowledge, participants indicated on a three-point scale (1 = knows nothing, 3 = knows a lot) the level of their parents’ knowledge regarding friends, location, and activities during free time. Both support and knowledge related to the period prior to age 16. Each question was answered separately for mother and father, resulting in four items for support (α = .82) and six items for knowledge (α = .84).

Sexual Behavior

Sexual behavior encompassed two single-item measures. Age of first sexual intercourse was reported in years and could range from before age 8 through age 24. Number of sexual partners was assessed by an open-ended question (viz., “With how many persons did you have vaginal and/or anal intercourse?”). This measure was corrected for outliers (defined as two standard deviations above the mean).

Protection Against Unwanted Pregnancy and STIs

This measure encompassed contraceptive and condom use, both with regard to the last partner with whom the participant engaged in sexual intercourse. Participants were asked whether or not they used contraception and condoms. Contraception encompassed hormonal contraception methods, intra-uterine devices, and barrier methods. Responses were never, sometimes, or always.

Social Skills in Sexual Interactions

To assess this concept, we constructed a measure based on the Sexual Interactional Behavior Scale (Vanwesenbeeck et al. 1998). Scores were analyzed using principle components factor analysis and revealed four subscales: communicative skills (6 items regarding the perceived ability to talk to the partner about sexual likes and dislikes, contraception and condoms, and previous sexual experiences, α = .90), sexual control (3 items, e.g. “I have little influence on what happens during sex (reversed)”, α = .68), sexual assertiveness (3 items, e.g. “I make it very clear what I want in sex”, α = .78), and sexual esteem (2 items, e.g. “I feel uncertain about my body while having sex” (reversed), α = .78). Participants indicated how much they agreed with these items on a five-point scale (1 = totally disagree, 5 = totally agree).

Sexual Satisfaction

Participants responded to four items regarding their satisfaction with the frequency of their sexual interactions, contact with sexual partners, pleasantness of sexual interactions, and their sex life in general (α = .86). Participants indicated their level of satisfaction on a five-point scale (1 = very unsatisfied, 5 = very satisfied).

Procedure

Participants were recruited in two ways. Middle and high school students came from 29 randomly selected schools, geographically spread over the Netherlands. Furthermore, in the municipalities where these high schools were located, individuals 17–25 years of age were randomly selected from the Municipal Basic Administration (MBA). The MBA is a database containing demographic information about the residents of a municipality, available at every city hall in the Netherlands, which can be consulted for scientific purposes.

Prior to the study, high school students received a letter at school to take home to their parents, in which parents were informed about the study and the possibility to refuse their child’s participation. Five percent of the selected students did not participate because of their own refusal, their parents’ refusal, or their absence during data collection. Participants who were selected from the municipal database received a letter in which they were invited to participate. Seventy-six percent of these youth did not respond to our invitation. The total sample was compared to the general population (using figures of Statistics Netherlands) on a number of demographic measures: sex, age, ethnic background, educational level, and religion. None of these comparisons showed significant differences.

Participants recruited in high schools completed the questionnaire during a regular class period, while participants who responded positively to a letter of invitation completed the questionnaire at home. All participants completed the questionnaire online.

Statistical Analyses

Preliminary analyses were conducted to investigate gender differences and differences between early, middle, and late adolescents in the study variables, using univariate analyses of variance (ANOVA). We controlled for age (in the analyses on gender), gender (in the analyses on age group), educational level, and ethnic background in these analyses.

According to Baron and Kenny (1986), for parental knowledge or support to function as a mediator between the other parenting variable and the dependent measures, the following associations have to be significant: (1) between support and knowledge (2) between knowledge and the dependent variables and (3) between support and the dependent variables. This was tested using Pearson’s correlations, separately for males and females and different age groups. Age and gender differences on the associations were tested by comparing correlation coefficients.

Subsequently, we followed the recommendations of Baron and Kenny (1986), and conducted a series of two-step hierarchical regression analyses, one for each dependent variable for which the previously mentioned associations were significant. We controlled for age, gender, educational level, and ethnic background in these analyses. The first hypothetical model (mediation of support by knowledge) included parental support in the first step and added knowledge in the second step. The second model (mediation of knowledge by support) included parental knowledge in the first step and added support in the second step. Both regression analyses tested whether the effect of either support or knowledge on the dependent measures was decreased (partial mediation) or absent (full mediation) after controlling for the other measure. We used Sobel’s test (Baron and Kenny 1986) to test for significance.

Results

Table 1 contains the means and standard deviations for males and females, and early, middle and late adolescents on the predictive and dependent measures. Gender and age group differences varied by the measure in question. Parental support showed neither differences by gender, nor by age group. Age of first intercourse showed no gender differences, while contraceptive use and sexual satisfaction showed no age group differences. Females had a slightly higher score on parental knowledge than males. As could be expected (Baumeister 2000), females’ mean number of sexual partners was lower. Females also used condoms less often with their last partner compared to males, they had higher scores on sexual communication, sexual control, and sexual satisfaction, were less sexually assertive and had lower sexual esteem.

Middle- and late-adolescents reported that their parents know more about them than early adolescents. Logically, the age of first intercourse (due to our restriction to sexual experienced youth) and the number of sex partners increased with age. The same was true for scores on communicative skills and sexual assertiveness, whereas condom use decreased with age. The largest increase in sexual control occurred between early (age 12–16) and middle (age 17–20) adolescence. Late (age 21–24) adolescents had higher sexual esteem than younger adolescents.

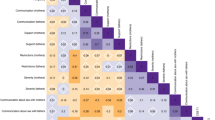

Table 2 shows age- and gender-specific correlations between support and knowledge, and between both of these parenting dimensions and measures of sexual behavior and sexual health. We found a strong association between parental support and knowledge for both males and females and all three age groups, satisfying the first condition for mediation. For both males and females, higher levels of parental support and knowledge were related to fewer sexual partners, more consistent contraceptive use, better communicative skills, and higher levels of assertiveness and satisfaction. For females, additional associations were found with a later sexual debut, and higher levels of sexual control and esteem. Correlations between support and parental knowledge, age of first sexual intercourse, and sexual control were stronger for females than for males. No gender-specific correlations existed for parental knowledge in relation to sexual behavior and sexual health.

In the youngest age group (age 12–16), both parental support and knowledge related positively to sexual satisfaction. Higher levels of parental knowledge was additionally correlated with an older age of first intercourse and fewer sex partners. In the other age groups, more associations were found, possibly (partly) because of a larger sample size. In middle adolescents (age 17–20), many correlations were significant at the p < .05 level, except for associations of parental support with knowledge, condom use, age of first intercourse, and sexual esteem. Among late adolescents (age 21–24), parental knowledge and support showed modest but significant correlations with all sexuality measures. Only one correlation, between parental knowledge and communicative skills, appeared to vary with age.

Table 3 shows the results of the two-step regression analyses testing for mediation. Because we found only a few age- and gender-specific bivariate correlations, we had no reason to expect the mediating effects to be different for males versus females, or between early, middle and late adolescents. We executed these analyses, therefore, for the whole sample, herewith controlling for age, gender, educational level, and ethnic background. These analyses were restricted to those dependent measures that correlated significantly with both parental support and knowledge (i.e., all measures except condom use).

The majority of the results supported the first hypothetical model, which proposed that support is mediated by knowledge. We found full mediation by knowledge for the associations between parental support and age of first intercourse, number of sexual partners, contraceptive use with the last partner, communicative skills, sexual control, and sexual esteem. For only two associations, the results suited the first model (mediation by knowledge) as well as the second model (mediation by support). The zero-order correlations with parental knowledge and support decreased (partial mediation) for sexual assertiveness and sexual satisfaction, after controlling for the other parenting measure.

Discussion

Parenting and Sexual Health

The first purpose of this study was to describe associations between parenting and a broad range of sexual health aspects: age of first sexual intercourse, number of sex partners, protection against STIs and unwanted pregnancy, social skills in sexual interactions, and sexual satisfaction. For most of these sexual health measures, associations existed with both parental support and knowledge of the child’s whereabouts, though these relationships sometimes differed by gender and age group. Parental support and knowledge apparently correlate not only with a later age of first intercourse, as is frequently documented (Bates et al. 2003; Bersamin et al. 2008; Hope and Chapple 2005; Johnson and Tyler 2007; Pedersen et al. 2003), but also with having safe and pleasurable experiences.

There are a number of possible explanations for the positive associations between parental support and knowledge and sexual health. Earlier research has demonstrated the positive relationship between parental support and adequate social skills (Barber 1997; Engels et al. 2002). The link between higher levels of parental knowledge and the tendency of adolescents to self-disclose also suggests a positive association between parental knowledge and adequate communication skills (Kerr et al. 2003). In addition, positive exchanges between parents and children could set an example for other social interactions, including sexual relations (Collins and Steinberg 2006). Consequently, young people who grow up in well-informed and supportive families could be more capable of realizing their own sexual needs.

Another explanation could be that adolescents who are close to their parents are more inclined to live up to their parents’ expectations. According to sexual socialization theory, parental influence on children’s sexual attitudes is larger when the parent-child relationship is closer (Fingerson 2005). Because many parents would like to see their children postponing intercourse and behaving responsibly, higher levels of support could result in their children actually behaving in such a way. A common explanation for the favorable associations with parental knowledge is that, by means of being informed, parents are capable of steering and correcting the behavior of their children when necessary (Kerr et al. 2003). Numerous, indirect associations are also conceivable. Associations have been found between parental knowledge and the selection of peers, for example, and presumably also the romantic partner (Kerr et al. 2003). Subsequently, the choice of romantic partners could have an effect on the quality of sexual interactions.

Parental support and knowledge did not relate to all sexual measures in this study. The use of condoms, for example, did correlate with parental support in males, but not in females. Furthermore, both knowledge and support only correlated with condom use among late adolescents. Condom use, however, may not be a comprehensive indication of sensible decision making considered apart from the other measures of sexual health. Other “wise” decisions can also be made in STI prevention, such as having a monogamous relationship with someone who is tested for STIs.

Age and Gender Specific Associations

The second purpose of this study was to explore whether the associations described above were specific to gender and age. The results showed that parental support seems to hold more systematic associations with daughters’ sexual development, as compared to sons’. Associations of parental support with both age of sexual intercourse and sexual control were stronger for females. This corresponds to findings in earlier studies that have reported stronger links between parental support and experience with sexual intercourse in females, as compared to males (Davis and Friel 2001; McNeely et al. 2002; Rose et al. 2005). This finding is in accordance with the theory of female erotic plasticity (Baumeister 2000), which states that female sexuality is, in general, more changeable according to circumstances and more susceptible to social influences than is male sexuality. Male sexuality, in turn, is more directly tied to biological factors than is female sexuality. The stronger links with parental support for females, however, probably extend beyond sexual behavior and sexual health. Previous research on parental support and emotional well-being found similar gender differences (Helsen et al. 2000). This gender difference could possibly be ascribed to the fact that low levels of parental support are more unusual for girls than for boys (Soenens et al. 2006).

Age-specific associations appeared to be almost absent, likely because of sample composition and the measurement of parental knowledge and support. The sample was limited to sexually experienced individuals, who generally report that their parents know less about them than their inexperienced contemporaries do, possibly because sexual status associates with a certain degree of independence from parents. This restriction of our sample resulted in lower scores on parental knowledge among the younger age groups, in contrast to what is generally found in research on knowledge of the child’s whereabouts. In addition, parental support and knowledge were measured retrospectively for participants older than 16. This could explain why the associations with both measures of parenting were almost equal for middle and late adolescents. Apparently, the associations between parental support and knowledge during early adolescence and subsequent sexual outcomes remain equally strong during middle and late adolescence.

Testing Two Meditational Models

The third purpose of the present study was to examine two different pathways for explaining these associations: mediation of support by knowledge, and mediation of knowledge by support. The results showed a mediational role of parental knowledge with regard to almost all dependent measures. Parental support correlated with higher scores on knowledge, which in turn correlated with a later age of first intercourse, less sexual partners, more consistent contraceptive use, and higher scores on social skills in sexual interactions.

Thus, although support and knowledge are related, parental knowledge is related more strongly to sexual behavior and sexual health. Knowledge of the child’s whereabouts is essential for parents to have some sort of influence during early and middle adolescence, because adolescents are gradually spending more and more time outside of direct parental supervision. This knowledge enables parents to give their children feedback on their experiences and decisions, possibly resulting in improving this decision making. Previous research revealed adolescents’ self-disclosure to be the major source of this parental knowledge (Keijsers et al. 2009; Stattin and Kerr 2000). A potential underlying mechanism could be that higher levels of parental support enhance positive feelings about the parents, and therefore higher levels of self-disclosure in their children (Kerr et al. 2003; Soenens et al. 2006). Subsequently, these parents have more knowledge of their child’s whereabouts.

As stated before, the association between parental knowledge and support is presumably bidirectional. Higher levels of knowledge also evoke higher levels of trust and more positive reactions in the parents (Kerr et al. 1999, 2003). Therefore, the present study also investigated whether parental support mediates the association between parental knowledge and sexual behavior and sexual health. This pathway appeared to fit only a few associations. The correlations between knowledge and sexual assertiveness and satisfaction were partially mediated by parental support.

Suggestions for Future Research

The present study has a number of limitations. First, the reliance upon a cross-sectional design makes conclusions about causal relationships impossible. In the hypothetical models tested in this study, we assumed parental support and knowledge preceded sexual behavior and sexual health. As mentioned before, the reverse causal pathway could also exist. This should be investigated more carefully in the future, preferably by studies with a longitudinal design.

A second limitation is the small amount of variance in the dependent measures that could be accounted for by both support and knowledge. The complex nature of these behaviors, cognitions, and emotions did not lead us to expect otherwise, however. A multitude of factors would be necessary in order to provide an extensive explanation for developing certain sexual characteristics and skills. In addition to parents, peers and sexual partners are also important environmental factors, and numerous internal processes will explain why individuals respond to these influences in different ways. Investigating these complex processes provides a challenge for future studies. Furthermore, it would be interesting to test the moderating effect of support on parental knowledge. Possibly, parental knowledge has a stronger link to sexual outcomes at higher levels of parental support.

Despite these limitations, this research is the first to provide evidence that both parental support and knowledge have beneficial associations with the use of contraceptives, social skills in sexual interactions, and sexual satisfaction in a national representative sample. In addition, this study is the first to disentangle the relative contributions of parental support and knowledge in predicting sexual development. The majority of the correlations with support can be ascribed to the relationship between a supportive family environment and parental knowledge of their child’s whereabouts. Parental knowledge thus appeared to be more important for healthy sexual development than parental support. However, parental support is very important in gaining this knowledge. If it is true that parental knowledge is most often the result of spontaneous self-disclosure on the child’s part (Stattin and Kerr 2000), then parents should create a family climate that facilitates self-disclosure. Support could be an important characteristic of such a family climate.

References

Barber, B. K. (1997). Adolescent socialisation in context - The role of connection, regulation, and autonomy in the family. Journal of Adolescent Research, 12, 5–11.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Bates, J. E., Alexander, D., Oberlander, S., Dodge, K. A., & Pettit, G. S. (2003). Antecedents of sexual activity at ages 16 and 17 in a community sample followed from age 5. In J. Bancroft (Ed.), Sexual development in childhood (pp. 206–237). Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Baumeister, R. F. (2000). Gender differences in erotic plasticity: The female sex drive as socially flexible and responsive. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 347–374. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.126.3.347.

Bersamin, M., Todd, M., Fisher, D. A., Hill, D. L., Grube, J. W., & Walker, S. (2008). Parenting practices and adolescent sexual behavior: A longitudinal study. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 70, 97–112.

Borawski, E. A., Ievers-Landis, C. E., Lovegreen, L. D., & Trapl, E. S. (2003). Parental monitoring, negotiated unsupervised time, and parental trust: The role of perceived parenting practices in adolescent health risk behaviors. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 33, 60–70. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(03)00100-9.

Coley, R. L., Medeiros, B. L., & Schindler, H. S. (2008). Using sibling differences to estimate effects of parenting on adolescent sexual risk behaviors. Journal of Sexual Health, 43, 133–140.

Collins, W. A., & Steinberg, L. (2006). Adolescent development in interpersonal context. In N. Eisenberg, W. Damon, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3, Social, emotional, and personality development (pp. 1003–1067). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Crosby, R. A., DiClemente, R. J., Wingood, G. M., & Harrington, K. (2002a). HIV/STD prevention benefits of living in supportive families: A prospective analysis of high risk African American female teens. American Journal of Health Promotion, 16, 142–145.

Crosby, R. A., DiClemente, R. J., Wingood, G. M., Lang, D. L., & Harrington, K. (2002b). Infrequent parental monitoring predicts sexually transmitted infections among low-income African American female adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 157, 169–173.

Davis, E. C., & Friel, L. V. (2001). Adolescent sexuality: Disentangling the effects of family structure and family context. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 63, 669–681. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00669.x.

De Graaf, H., Meijer, S., Poelman, J., & Vanwesenbeeck, I. (2005). Seks onder je 25 e : Seksuele gezondheid van jongeren in Nederland anno 2005 [Sex under 25: Sexual health of young people in the Netherlands in the year 2005]. Delft, The Netherlands: Eburon.

Dittus, P. J., & Jaccard, J. (2000). Adolescents’ perceptions of maternal disapproval of sex: Relationship to sexual outcomes. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 26, 268–278. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(99)00096-8.

Engels, R. C. M. E., Dekoviç, M., & Meeus, W. (2002). Parenting practices, social skills and peer relationships in adolescence. Social Behavior and Personality, 30, 3–18. doi:10.2224/sbp.2002.30.1.3.

Fingerson, L. (2005). Do mothers’ opinions matter in teens’ sexual activity? Journal of Family Issues, 26, 947–974. doi:10.1177/0192513X04272758.

Furman, W., Ho, M. J., & Low, S. M. (2007). The rocky road to adolescent romantic experience: Dating and adjustment. In R. Engels, M. Kerr, & H. Stattin (Eds.), Friends, lovers and groups: Key relationships in adolescence (pp. 93–104). Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Helsen, M., Vollebergh, W., & Meeus, W. (2000). Social support from parents and friends and emotional problems in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 29, 319–335. doi:10.1023/A:1005147708827.

Hope, T. L., & Chapple, C. L. (2005). Maternal characteristics, parenting, and adolescent sexual behavior: The role of self-control. Deviant Behavior, 26, 25–45. doi:10.1080/016396290500405.

Huebner, A. J., & Howell, L. W. (2003). Examining the relationship between adolescent sexual risk-taking and perceptions of monitoring, communication, and parenting styles. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 33, 71–78. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(03)00141-1.

Hull, T. H. (2008). Sexual pleasure and well-being. International Journal of Sexual Health, 20, 133–145.

Johnson, K. A., & Tyler, K. A. (2007). Adolescent sexual onset: An intergenerational analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36, 939–949. doi:10.1007/s10964-006-9165-z.

Kerr, M., Stattin, H., Biesecker, G., & Ferrer-Wreder, L. (2003). Relationships with parents and peers in adolescence. In R. M. Lerner, M. A. Easterbrooks, & J. Mistry (Eds.), Handbook of psychology (Volume 6: Developmental Psychology) (pp. 395–422). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Kerr, M., Stattin, H., & Trost, K. (1999). To know you is to trust you: Parents’ trust is rooted in child disclosure of information. Journal of Adolescence, 22, 737–752. doi:10.1006/jado.1999.0266.

Keijsers, L., Branje, S., Van der Valk, I., & Meeus, W. (2009) Reciprocal effects between parental solicitation, parental control, adolescent disclosure and adolescent delinquency. Journal of Research on Adolescence (in press).

Lammers, C., Ireland, M., Resnick, M., & Blum, R. (2000). Influences on adolescents’ decision to postpone onset of sexual intercourse: A survival analysis of virginity among youths aged 13 to 18 years. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 26, 42–48. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(99)00041-5.

Maccoby, E., & Martin, J. (1983). Socialization in the context of the family. Parent-child interaction. In E. M. Hetherington (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology (Vol. 4, pp. 1–101). New York: Wiley.

McNeely, C., Shew, M. L., Beuhring, T., Sieving, R., Miller, B. C., & Blum, R. W. (2002). Mothers’ influence on the timing of first sex among 14- and 15-year-olds. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 31, 256–265. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(02)00350-6.

Meeus, W., Branje, S., & Overbeek, G. J. (2004). Parents and partners in crime: A six-year longitudinal study on changes in supportive relationships and delinquency in adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 45, 1288–1298. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00312.x.

Meeus, W., Iedema, J., Maassen, G., & Engels, R. (2005). Separation–individuation revisited: On the interplay of parent–adolescent relations, identity and emotional adjustment in adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 28, 89–106. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.07.003.

Ojanlatva, A., Helenius, H., Tautava, P., Ahvenainen, J., & Koskenvuo, M. (2003). Will childhood relationships with parents contribute to a satisfying sex life? Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 18, 205–214. doi:10.1080/1468199031000099433.

Pedersen, W., Samuelsen, S. O., & Wichstrøm, L. (2003). Intercourse debut age: Pour resources, problem behavior, or romantic appeal? A population based longitudinal study. Journal of Sex Research, 40, 333–345.

Rispens, J., Hermanns, J. M. A., & Meeus, W. H. J. (1996). Opvoeden in Nederland. [Childrearing in The Netherlands]. Assen, The Netherlands: Van Gorcum.

Rose, R. J., Dick, D. M., Viken, R. J., Pulkkinen, L., & Kaprio, J. (2001). Drinking or abstaining at age 14: A genetic epidemiological study. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 25, 1594–1604. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2001.tb02166.x.

Rose, A., Koo, H. P., Bhaskar, B., Anderson, K., White, G., & Jenkins, R. R. (2005). The influence of primary caregivers on the sexual behavior of early adolescents. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 37, 135–144. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.02.009.

Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Luyckx, K., & Goossens, L. (2006). Parenting and adolescent problem behavior: An integrated model with adolescent self-disclosure and perceived parental knowledge as intervening variables. Developmental Psychology, 42, 305–318. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.305.

Sionéan, C., DiClemente, R. J., Wingood, G. M., Crosby, R., Cobb, B. K., Harrington, K., et al. (2002). Psychosocial and behavioral correlates of refusing unwanted sex among African American adolescent females. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 30, 55–63. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(01)00318-4.

Stattin, H., & Kerr, M. (2000). Parental monitoring: A reinterpretation. Child Development, 71(4), 1072–1085. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00210.

Stone, N., & Ingham, R. (2002). Factors affecting British teenagers’ contraceptive use at first intercourse: The importance of partner communication. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 34, 191–197. doi:10.2307/3097729.

Vanwesenbeeck, I., Bekker, M., & van Lenning, A. (1998). Gender attitudes, sexual meanings and interactional patterns in heterosexual encounters among college students in The Netherlands. Journal of Sex Research, 35(4), 317–327.

Vanwesenbeeck, I., van Zessen, G., Ingham, R., Jaramazovič, E., & Stevens, D. (1999). Factors and processes in heterosexual competence and risk: An integrated review of the evidence. Psychology & Health, 14, 25–50. doi:10.1080/08870449908407312.

Whipple, B. (2007). The health benefits of sexual expression. In M. S. Tepper & A. F. Owens (Eds.), Sexual health, volume 1: Psychological foundations (pp. 17–41). Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers.

Acknowledgments

“Sex under the age of 25” was conducted by the Rutgers Nisso Groep and STI Aids Netherlands. Financial Support has been received from the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMW). The authors would like to thank Jos Poelman for his contributions in preparing the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

de Graaf, H., Vanwesenbeeck, I., Woertman, L. et al. Parental Support and Knowledge and Adolescents’ Sexual Health: Testing Two Mediational Models in a National Dutch Sample. J Youth Adolescence 39, 189–198 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-008-9387-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-008-9387-3