Abstract

A sample of 679 (341 women) emerging adults (M = 18.90 years; SD = 1.11; range = 18.00–22.92) participated in a study on the utility of forms (i.e., physical and relational) and functions (i.e., proactive and reactive) of aggression. We examined the link between these four subtypes of aggression and personality pathology (i.e., psychopathic features, borderline personality disorder features, and antisocial personality disorder features). The study supports the psychometric properties (i.e., test–retest reliability, internal consistency, discriminant validity) of a recently introduced measure of forms and functions of aggression during emerging adulthood. Aggression subtypes were uniquely associated with indices of personality pathology. For example, proactive (i.e., planned, instrumental or goal-oriented) and reactive (i.e., impulsive, hostile or retaliatory) functions of relational aggression were uniquely associated with borderline personality disorder features even after controlling for functions of physical aggression and gender. The results highlight the differential associations between forms and functions of aggression and indices of personality pathology in typically developing emerging adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Aggression is a developmentally salient behavior from early childhood to adulthood and a common symptom in several disorders and syndromes of psychiatric concern, particularly personality disorders. The psychological and psychiatric literatures have delineated two primary function types of aggression, which are given various names (e.g., proactive or reactive; premeditated or impulsive; predatory or defensive; cold blooded or hot blooded; instrumental or hostile, see Dodge 1991; Houston et al. 2003), but essentially delineate aggressive behavior that is controlled/planned versus behavior that is more retaliatory/impulsive. In the present study and in keeping with the developmental literature (e.g., Dodge and Coie 1987; Vitaro et al. 1998) we use the terms proactive to note aggressive behaviors that are displayed to serve an instrumental, goal-directed end and reactive aggressive behavior that is in response to a threat or perceived threat and associated with negative affect (i.e., hostility or anger).

Functions of Aggression

The two main functions of aggression are supported by different theoretical orientations, with proactive aggression being conceptually rooted in the Social Learning Theory (Bandura 1973) and reactive aggression being a product of the Frustration Aggression Hypothesis (Berkowitz 1963). Recently there has been a critical analysis of these constructs and some calls of caution suggesting that a dichotomous view of functions of aggression is not appropriate. That is, given the theoretical and empirical overlap between proactive and reactive aggression and since a categorical analysis precludes an assessment of the multiple motives individuals have for aggression, a dimensional approach should be used (Bushman and Anderson 2001). These authors do support the continued study of proactive and reactive functions, which is further bolstered by numerous studies that have demonstrated the utility of these constructs. For example, past research has supported a two (e.g., Poulin and Boivin 2000) or three factor solution that includes the interaction between proactive and reactive aggression (Fite et al. 2006) and the discriminant validity of the constructs (e.g., Crick and Dodge 1996; Price and Dodge 1989; Hubbard et al. 2002). In sum, theoretical justification for the distinction between proactive and reactive functions of aggression is robust (Dodge 1991).

Reactive and proactive functions of physical aggression have been differentially associated with unique behavioral and physiological profiles. That is, children high in reactive physical aggression have been found to have high levels of hostile attribution biases for ambiguous instrumental provocation situations (Crick and Dodge 1996) and have been found to have greater social-emotional, behavioral and attention problems (Day et al. 1992; Hubbard et al. 2001; Raine et al. 2006; Schwartz et al. 1998; Waschbusch et al. 2002). Reactive, but not proactive, aggression has been associated with physiological (i.e., skin conductance reactivity) and nonverbal indicators of anger (Hubbard et al. 2002, 2004). Impulsive aggression (i.e., reactive) has been found to be more highly associated with anger (Stanford et al. 2003) and related to deficits in frontal brain function and sensory processing (Barratt 1997a, 1997; Houston and Stanford 2006; Houston et al. 2003; Raine et al. 1998; Stanford et al. 1997). On the other hand, proactive aggression has been associated with delinquency, disruptive disorders, blunted affect, psychopathy and serious offending in children and adolescents (Frick et al. 2003; Pulkkinen 1996; Raine et al. 2006; Vitaro et al. 1998; cf. Fite and Colder 2007). Furthermore, proactive aggression has been uniquely associated with evaluating aggression as more positive and effective than reactive aggressors (Crick and Dodge 1996). Event related potential (ERP) and functional neuroimaging studies in adults characterized as primarily proactive/premeditated indicate few deficits in neurocognitive processing (Barratt et al. 1997a; Houston et al. 2003; Raine et al. 1998; Stanford et al. 2003). In a further attempt to understand differences in aggressive subtypes, researchers have also explored forms of aggression.

Forms of Aggression

Researchers in developmental psychology and psychopathology explore differences in physical and relational forms of aggression. Aggression is typically defined as the intent to hurt, harm or injure another person and hundreds of studies have been conducted to investigate the development of physical aggression, which is defined as the use of physical force or the threat of force as the means of harm (e.g., hitting, kicking, pushing; see Dodge et al. 2006). Physical aggression tends to drop off dramatically after early childhood, but for a subset of children chronic aggression continues into adolescence (see Cote et al. 2006; NICHD ECCRN 2004) and beyond (Moffitt 1993). Relational aggression has been defined as aggression displayed to damage or destroy relationships or the threat of relationship removal (Crick and Grotpeter 1995). Relational aggression may be displayed both directly (e.g., telling a peer that they no longer may be your friend) and covertly (e.g., spreading malicious rumors, gossip or lies about another person), arguably with more subtle manifestations occurring during adolescence and emerging adulthood (Crick et al. 2007). Relational aggression is conceptually related but distinct from other developmentally important constructs including indirect aggression in which the perpetrator is usually not known (Lagerspetz et al. 1988) and social aggression, which includes verbal insults and nonverbal gestures not part of the relational aggression construct (Galen and Underwood 1997).

Relational aggression has been found to be associated with a range of psychopathology from ADHD (Zalecki and Hinshaw 2004) to personality pathology (Crick et al. 2005; Marsee and Frick 2007; Miller and Lynam 2003). Specifically with respect to personality disorder symptomatology, Crick et al. (2005) found that a self-report of borderline personality disorder (BPD) features in middle childhood was uniquely related to teacher-reported relational aggression even after controlling for physical aggression and depressive symptoms, which is consistent with available theory (Geiger and Crick 2001). In a second study with emerging adults affiliated with fraternities and sororities, Werner and Crick (1999) documented that peer-reported relational aggression was significantly associated with self-reported borderline personality features. Given the BPD symptoms of intense anger, affective instability, impulsivity, and unstable interpersonal relationships, an association between BPD symptoms and relational aggression, particularly reactive relational aggression, is plausible and warrants further investigation. In addition, Werner and Crick (1999) revealed that two subscales (i.e., stimulus-seeking and egocentricity) of measures of antisocial personality disorder (APD) were associated with relational aggression. Relational aggression has also been found to be uniquely associated with psychopathy in emerging adulthood (Miller and Lynam 2003). Thus, relational aggression may have unique associations with several indices of personality pathology across development.

Emerging Adulthood

Emerging adulthood (18- to 25-years-old) is a transitional period of development in Western, industrialized societies characterized by important developmental changes (i.e., biological, cognitive and social) marked in part by the further separation/independence from caregivers, identity moratorium, the salience of peer and romantic relationships, fundamental shifts in moral reasoning, an increase in risk-taking behaviors, and changes in cognitive flexibility (Arnett 2000; Spear 2000). Recent findings regarding the role of romantic relationships support the notion that emerging adulthood is qualitatively and quantitatively distinct from adolescence for a high risk, low SES sample (van Dulmen et al. 2008). Some traditional cultures (e.g., Chinese) or sub-groups within industrialized societies do not have an emerging adult developmental period (Nelson et al. 2004) and this finding is consistent with Arnett’s (2000) theory. The perceived criteria that contemporary emerging adults have adopted for this period have been replicated in a variety of cultures, ethnic and religious groups (see Nelson et al. 2007). However, not all individuals during this developmental period consider themselves to be emerging adults, with about 25% of youth reporting that they have reached adulthood and have assumed adult responsibilities (e.g., marriage, raising children, achieving financial and residential independence; Arnett 1994; Arnett and Taber 1994).

Emerging adulthood most importantly represents a salient developmental period in the evolution of personality traits, and consequently, personality disorders (Johnson et al. 2006). To date only a handful of studies have investigated relational and physical aggression during this developmental period. For example, Loudin et al. (2003) found that fear of negative evaluation was associated with relational aggression (Loudin et al. 2003). In addition, reactive relational aggression has been associated with exclusionary behavior and fewer prosocial behaviors (Lento-Zwolinski 2007). Recently Goldstein et al. (2008) reported that individuals that perpetrated relational aggression within a romantic relationship were more likely to have high levels of exclusivity in their relationship and higher symptoms of anxiety and depression than non-relationally aggressive emerging adults. Finally, Storch et al. (2004) have revealed that relational aggression uniquely predicted social anxiety, internalizing problems and substance use problems. Thus, during this developmental period, relational aggression is associated with indices of psychopathology. Despite recent tests supporting the utility of assessing both form and function of aggression from early childhood to adolescence (Little et al. 2003; Fite et al. in press; Marsee and Frick 2007; Ostrov and Crick 2007; Prinstein and Cillessen 2003) and calls for additional studies (Werner and Nixon 2005), no known studies have been conducted in the emerging adult period.

Hypotheses

In order to understand potential risk factors for personality pathology across development, it is important to explore the utility of proactive and reactive physical and relational aggression during emerging adulthood. Given that proactive and reactive aggression and physical and relational aggression are typically highly correlated, when using self-report methods (see Little et al. 2003), it is important to control for the influence of other subtypes in analyses, but rarely is this procedure followed. We test theoretically driven hypotheses with a large sample of emerging adults. Associations between aggression subtypes and various salient markers of personality pathology are conducted. These indices of personality pathology were carefully selected based on past literature to test the utility of the forms and functions of aggression approach in emerging adulthood.

This study had several empirical goals and hypotheses. The first key study goal was to explore the association between the four aggression constructs and various salient markers of personality pathology. Thus, we conducted bivariate associations as well as Fisher r to Z tests to explore the relative difference in magnitude between the constructs and indices of personality pathology. The second key study goal builds on these analyses by testing the unique associations between the four aggression subtypes and four personality pathology measures in a series of hierarchical regression models. Based on past theory and empirical work, we hypothesized that proactive functions of physical and relational aggression would be uniquely associated with psychopathic traits, especially in male participants. These predictions are based on past literature pertaining to physical aggression (Frick et al. 2003; Kimonis et al. 2006; Miller and Lynam 2003), and to our knowledge, no studies have been conducted on the relation between functions of relational aggression and psychopathic traits during emerging adulthood. However, Miller and Lynam (2003) found that self-reported relational aggression was associated with psychopathy more so for women than for men during emerging adulthood. Moreover, Marsee and Frick (2007) found that proactive relational aggression was uniquely associated with callous-unemotional (CU) traits (i.e., failing to display empathy or guilt and hallmark features of psychopathy, Frick et al. 2000) among detained adolescent girls. Thus, for the functions of relational aggression and psychopathic traits we hypothesized findings analogous to those we expected for physical aggression. Next, we hypothesized that relational aggression and in particular reactive functions of relational aggression would be associated with borderline personality disorder features (Crick et al. 2005). Finally, we hypothesized that physical forms of aggression (i.e., reactive and proactive) would be associated with antisocial personality disorder symptoms as physical aggression is a potential criteria for the APD diagnosis (APA 2000) and studies of APD have documented both impulsive and premeditated forms of aggression (Barratt et al. 1999). In order to test these goals and hypotheses, we recruited a large sample of emerging adults and administered aggression and personality pathology measures at two different time points.

Method

Participants

A large sample of 679 (341 women) emerging adults (M = 18.9 years; SD = 1.11; range = 18.00–22.92), attending a research university in a large northeastern city completed a questionnaire battery in the laboratory in exchange for partial course credit. About half (52%) were European American, 11% African American, 8% Asian American, 5% Latino, 4% Other and 20% did not disclose ethnicity. Participants provided informed written consent and completed the questionnaires in a small group format via paper and pencil. Instructions were read aloud by the research assistant. Questionnaire administration typically lasted no more than 30 min. Participants were fully debriefed at the conclusion of the study. In addition, a subsample of these participants (n = 80; 31 women) returned to the laboratory to complete the SRASBM for test–retest purposes (mean duration of time between sessions was 29.29 days; SD = 28.36 days; median = 24 days). For purposes of the larger project, these participants passed a medical screening conducted during their first laboratory visit to verify that they could participate in an event related potential (ERP) study conducted during the second time point (administered after completing the self-report battery). Reported use of psychoactive medication, severe head injury, history of seizure activity, and neurological disorder served as exclusionary criteria.Footnote 1

Measures

Self-report of Aggression and Social Behavior Measure (SRASBM)

The SRASBM was developed by Morales and Crick (1998) and first published in Linder et al. (2002). This 39 item measure includes five items that assess proactive relational aggression (e.g., “I have threatened to share private information about my friends with other people in order to get them to comply with my wishes”) and six that assess reactive (e.g., “When I am not invited to do something with a group of people, I will exclude those people from future activities”) relational aggression. The measure also includes three items that assess proactive physical aggression (e.g., “I try to get my own way by physically intimidating others”) and three items that evaluate reactive physical aggression (e.g., “When someone makes me really angry, I push or shove the person”). Responses for all items range from (1) “Not at all true” to (7) “Very true”. Scoring is conducted by summing the items for each of the four respective aggression types. Past studies using the SRASBM have further supported the validity and internal consistency of the proactive and reactive functions of physical and relational aggression subscales (Bailey and Ostrov in press; Lento-Zwolinski 2007) and associated relational aggression scales (Goldstein et al. 2008; Miller and Lynam 2003; Schad et al. 2008). A recent confirmatory factor analysis of the SRASBM (N = 1387) has been conducted using Mplus and revealed the hypothesized factor structure and the model fit the data well (Murray-Close et al., 2008). This past study found that the inter-correlations among the latent constructs were high (e.g., proactive and reactive relational aggression, r = .85, p < .0001). These researchers reported that a competing model with a single factor did not fit the data as well. Finally, the standardized factor loadings were all above .58 (Murray-Close et al. 2008). In the present study, each subscale was reliable (Cronbach’s α > .71) at each time point with the exception of proactive relational aggression at time 1, that was slightly lower than convention (Cronbach’s α = .68). In the first known assessment of the test–retest reliability of this measure we found high levels of correspondence for each subscale across time (i.e., proactive relational aggression, r = .84; reactive relational aggression, r = .75; proactive physical aggression, r = .76; and reactive physical aggression, r = .81; p’s < .001).

Impulsive-premeditated Aggression Scales (IPAS; Stanford et al. 2003)

The IPAS is a 30 item self-report instrument developed to assess the impulsive and/or premeditated characteristics associated with an individual’s physically aggressive acts. Participants are asked to consider their aggressive acts over the last 6 months and complete the IPAS in relation to those acts. Fifteen of the items focus on impulsive aggressive (IA) characteristics and 15 items focus on premeditated aggressive (PM) characteristics. The items are scored on a six-point scale (strongly agree [5], agree [4], neutral [3], disagree [2], strongly disagree [1], not applicable [0]). The IPAS has been used to characterize physically aggressive behavior in several different samples including forensic patients (Kockler et al. 2006), opiate dependent men and women (Conner et al. 2007; Houston and Conner 2006), emerging adults (Haden et al. 2007), and conduct disordered adolescents (Mathias et al. 2007). Scoring is conducted by summing the items for each respective subscale. In the present study, this measure was used for validity purposes and impulsive-aggression (Cronbach’s α = .88) and premeditated aggression (Cronbach’s α = .89) were both internally consistent.

Psychopathic Personality Inventory (PPI; Lilienfeld and Andrews 1996; Wilson et al. 1999)

This 56 item short version of the original PPI measures eight core personality characteristics of psychopathy: machiavellian egocentricity, social potency, coldheartedness, carefree nonplanfulness, fearlessness, blame externalization, impulsive nonconformity, and stress immunity. The items are scored on a four-point scale (false [1], mostly false [2], mostly true [3], true [4]). Recent research (i.e., Benning et al. 2003, 2005) has indicated that these core psychopathic characteristics consistently load on two factors: (1) impulsive antisociality (28 items), that is comprised of machiavellian egocentricity, carefree nonplanfulness, blame externalization, and impulsive nonconformity; and (2) fearless dominance (28 items), that is comprised of social potency, fearlessness, and stress immunity. The coldheartedness subscale of the PPI does not typically load on either factor, however, these two factors are consistent with the extant literature on psychopathy (Hare 1991; Harpur et al. 1989). These subscales are scored by summing the items for the respective scale. In the current study, both factors were reliable (Cronbach’s α’s > .79).

Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire-4, Cluster B (PDQ-4; Hyler 2003; Hyler et al. 1990 )

The PDQ-4 is a self-administered, true/false questionnaire that yields symptom counts consistent with the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for the axis II disorders. Only those questions related to antisocial (eight items) and borderline personality disorders (nine items) were used for the current study as aggressive behavior is commonly associated with these two diagnoses. The PDQ-4 is scored by totaling the number of symptoms endorsed for each diagnosis. In the past this measure has revealed the hypothesized factor structure and demonstrated appropriate internal consistency using tetrachoric correlations for dichotomous data with emerging adult samples (e.g., Chabrol et al. 2007). Past scholars have suggested that internal consistency statistics are not meaningful for this instrument because the measure was not designed to achieve internal consistency but rather to be a checklist and resemble the symptoms included in the DSM-IV (McHoskey 2001). In the present study, we explored the reliability in our non-clinical sample and it was acceptable for antisocial personality disorder features (APD; K-R 20 = .81) and approached conventional levels for borderline personality disorder features (BPD; K-R 20 = .67). Although this sample was not recruited to represent clinical levels of personality disorder pathology, it is important to note that 85 participants (12.5%; 56 women) in our sample met the clinical threshold score (5 or more symptoms) for BPD. For APD, stringent criteria were used (i.e., endorsement of three conduct disorder and three APD symptoms) to determine the number of participants that met clinical threshold criteria for APD, (n = 45; 6.5%; 13 women). These figures should be interpreted with some caution as more in-depth assessment would be required to determine diagnostic efficacy based on these scores (Bagby and Farvolden 2004).

Results

Preliminary analyses consisted of descriptive statistics, bivariate correlations, Fisher Z tests between aggression subtypes, and two regression models exploring associations between the SRASBM and IPAS for validity purposes. Next, a series of four regression models were conducted with personality pathology indices serving as the respective dependent variable (in separate models). In each model, at step 1 gender and the four aggression subtypes (i.e., proactive and reactive physical and proactive and reactive relational aggression) were entered simultaneously. To test the potential for gender moderation (e.g., Zimmer-Gembeck et al. 2005), at step 2, the interactions between each aggression subtype and gender were simultaneously added. For ease of communication, only significant interactions with gender are presented.

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics were calculated for each study variable (see Table 1).Footnote 2 Measures of skew were <3 (−.10 to 1.94) and kurtosis were <8 (.05–4.61), suggesting that non-normality of the data was not a concern (Kline 1998).

Inter-correlations

The inter-correlations between proactive and reactive relational aggression were moderately to highly correlated. The inter-correlations between proactive and reactive physical aggression were highly correlated (see Table 1). The correlations between proactive relational and proactive physical aggression were moderately to highly correlated and the correlation between reactive relational and reactive physical aggression were low in magnitude (see Table 1). Inter-correlations at time 2 were similar (r = .67, p < .001 for proactive and reactive relational aggression, and r = .61, p < .001 for proactive and reactive physical aggression).

To explore possible gender differences for the inter-correlations, Fisher Z test analyses were conducted to compare the inter-correlations for males and females at time 1. The correlation between proactive relational and proactive physical aggression was significantly higher (Z = 2.07, p < .05) for males (r = .61) than for females (r = .50). No other differences emerged suggesting similar pattern of effects for males and females and thus, the entire sample is used in all subsequent analyses.

Bivariate Correlations

Correlations between the study variables are presented in Table 1. Given the sample size, most effects are significant. Moderate or medium effect sizes (r’s > .30) may be of most interest and are the only effects interpreted (Cohen 1988). Some interesting preliminary findings emerged, suggesting unique associations between aggression subtypes and various outcomes. In each case where unique associations were revealed, follow-up Fisher Z test statistics were conducted to examine if the magnitude of the correlations was significantly different for each of the aggression subtypes. According to the adopted criteria, only reactive relational aggression was associated with borderline personality disorder features and was not strongly associated with antisocial personality disorder features. For borderline personality disorder features, the correlation with reactive relational aggression was significantly higher than the correlation with reactive (Z = 3.65, p < .01) or proactive (Z = 3.21, p < .01) physical aggression, but there was not a significant difference between reactive and proactive relational aggression (Z = .32, ns).

Validity Findings

Bivariate correlations indicated that only proactive functions of aggression were strongly associated with premeditated aggression. However, Fisher Z tests indicated that whereas the correlation between proactive relational aggression and premeditated aggression was significantly higher than for the association between reactive relational aggression and premeditated aggression (Z = 2.40, p < .05), none of the other comparisons were statistically significant (Z’s from .48 to 1.49). Two regression models were conducted to further test the unique associations between the four aggression types and the IPAS. The first regression model revealed that only proactive relational aggression (β = .17, p < .001) was significantly associated with premeditated aggression when controlling for all other aggression types and gender, F(5, 639) = 22.90, p < .001, R 2 = .15. In the second regression model, only reactive function types [i.e., reactive relational (β = .13, p < .05) and reactive physical aggression (β = .11, p < .05)] were uniquely associated with impulsive aggression, controlling for gender and all other aggression subtypes, F(5, 649) = 11.66, p < .001, R 2 = .08. These findings are consistent with predictions and add validity to the SRASBM.

Regression Models

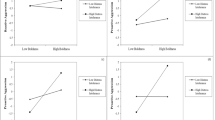

For each of the four main regression models, gender (1 = male; 2 = female) and the four aggression subtypes (i.e., proactive relational, reactive relational, proactive physical, and reactive physical aggression) were simultaneously entered at step 1. The interactions between gender and each of the four aggression subtypes were entered at step 2. In each model, for ease of communication, step 2 is only shown and discussed when significant.Footnote 3 In model one, reactive relational aggression was negatively associated and proactive physical aggression was positively associated with fearless dominance. In addition, men reported higher levels of fearless dominance than women. In model two, proactive relational, reactive relational and proactive physical aggression were all significantly associated with impulsive antisociality. In addition, men reported higher levels of impulsive antisociality than did women. The effects were in part qualified by an interaction between proactive relational aggression and gender. For women, proactive relational aggression was significantly associated with impulsive antisociality [β = .28, p < .001; F(4, 223) = 19.37, p < .001, R 2 = .26]. The effect was not significant for men. In model three, proactive and reactive functions of relational aggression were significantly associated with borderline personality disorder features, controlling for the other subtypes of aggression. In addition, women reported higher levels of borderline symptoms than men. In model four, all aggression subtypes except for reactive relational aggression were uniquely associated with antisocial personality disorder features. Gender was also significant, indicating that men reported more APD symptoms than women. No other significant effects were found (Table 2).

Discussion

The study was conducted during emerging adulthood, a developmental period marked by changes in risk taking behaviors, personality and identity formation. The study was developmentally appropriate and focused on the associations between aggression subtypes and indices of personality pathology. The present results indicate specific relations between the forms and functions of aggression and measures of personality pathology during emerging adulthood. These findings are consistent with prior studies examining subtypes of physical aggression (Frick et al. 2003; Kimonis et al. 2006). For example, reactive functions of aggression were uniquely associated with measures related to a lack of impulse control (e.g., impulsive aggression, antisocial behavior, borderline personality). Conversely, proactive functions of aggression appeared to have a unique relation to psychopathic features. In terms of personality disorder symptomatology, relational aggression was uniquely associated with the number of borderline symptoms. These results extend prior work and highlight the usefulness of assessing both form and functions of aggression with respect to personality pathology, particularly at this key developmental period.

With respect to psychopathic traits, the fearless dominance factor of the PPI assesses aspects such as superficial charm, sensation seeking tendencies, and low stress proneness. In this study, fearless dominance was uniquely associated with proactive physical aggression. This finding is consistent with previous literature in both adults (Woodworth and Porter 2002) and children (Frick et al. 2003; Kimonis et al. 2006) and extends the finding to emerging adults. The fact that reactive relational aggression was a unique negative predictor of fearless dominance also seems to be consistent with the notion that individuals high in psychopathic traits tend to use aggressive behavior in an instrumental fashion. In addition, this aspect of psychopathy may involve behaviors that are unlikely to be related to reactive aggression such as planfulness (e.g., manipulating or conning others, planning a risky endeavor such as sky diving) and remaining calm in stressful situations. Finally, the fact that male participants scored higher in fearless dominance is consistent with some of the previous literature on psychopathy and gender, although this area remains contentious (Forouzan and Cooke 2005; Hunt et al. 2005).

Unlike the fearless dominance factor, the impulsive antisociality factor of the PPI was positively correlated with all measures of aggression, regardless of form or function. However, the regression analyses indicated unique associations between impulsive antisociality and proactive relational, reactive relational and proactive physical aggression. As noted, associations between proactive aggression and psychopathic traits are consistent with previous literature, although this is typically with regard to proactive physical aggression. Interestingly, the association between proactive relational aggression and impulsive antisociality was qualified by an interaction with gender. For female participants, proactive relational aggression uniquely predicted impulsive antisociality. This was not the case for male participants. The impulsive antisociality factor represents behaviors and feelings such as lying, cheating, rebelliousness, using others, lack of direction/focus, hostility, and suspiciousness. Thus, it is not surprising that aggressive behaviors, particularly proactive aggressive behaviors (regardless of form), are associated with this factor. The fact that proactive relational aggression appears to be more relevant for women than men provides interesting insight into the role of relational forms of aggression and psychopathic/antisocial behavior. This finding is somewhat consistent with past studies that have found that relational aggression was associated with psychopathic features for women more so than for men during emerging adulthood (Miller and Lynam 2003) and that proactive relational aggression was associated with CU traits among detained adolescent girls (Marsee and Frick 2007), but comparisons are challenging given that different scales were used. Further research is necessary to accurately delineate these relations.

The positive unique relation between impulsive antisociality and reactive relational aggression on the other hand, is somewhat unexpected, but may suggest a different underlying mechanism for reactive functions of aggression. There may also be aspects of relational aggression, regardless of whether expressed in a reactive manner, that are relevant to behaviors or feelings tapped by the PPI impulsive antisociality factor (e.g., deceitfulness; Ostrov 2006), which may explain this unique association.

It appears that APD symptoms are not specific to reactive or proactive functions of physical aggression. Both reactive and proactive physical aggression were uniquely associated with the number of APD symptoms. This is consistent with prior studies demonstrating no differences in functions of physical aggression in individuals diagnosed with APD (Barratt et al. 1997a; Houston et al. 2003). Proactive relational aggression was also a unique predictor of APD symptoms. Traditionally, APD has been associated with physically aggressive behavior. However, the symptoms of this personality disorder include aspects that are assessed in proactive relational aggression as well. One example is deception, which has been shown to be uniquely associated with relational aggression in younger samples (Ostrov 2006). In addition, in adolescence, relational aggression among males is associated with weapon carrying suggesting that these possible links may be important (Goldstein et al. in press). Thus, although functions of physical aggression may not provide unique information for understanding the development of APD, these results suggest that further study of reactive and proactive relational aggression within this context may be warranted.

Analyses also indicated that both reactive and proactive relational aggression were uniquely associated with borderline personality disorder (BPD) symptoms. At first glance, the lack of an association with physical aggression, particularly reactive physical aggression, seems puzzling given that impulsivity is a hallmark feature of BPD. One possible explanation for this is that the sample used in the current study is relatively typical in functioning and likely to have a lower base rate of severe physical aggression and/or BPD symptoms. A second difference between the present study and past research is that functions of relational aggression were simultaneously included in the current models and relational aggression may account for most of the variance in predicting BPD symptoms (Crick et al. 2005). An association between relational forms of aggression and BPD symptoms seems plausible when considering other characteristics and behaviors common to the BPD diagnosis such as manipulation, unstable relationships and identity problems. In this vein, prior research on BPD features in children have demonstrated that once relational aggression is taken into account, physical aggression is not a significant predictor of BPD features (Crick et al. 2005). Furthermore, relational aggression and BPD symptoms were significantly related in a past sample of emerging adults (Werner and Crick 1999). Although the current study provides only a cursory assessment of BPD symptomatology, these results are encouraging and highlight the importance of examining both physical and relational aggression within the context of BPD.

As with any investigation, the current study has some limitations. First, these findings are based only on self-report measures (consistent with past studies, e.g., Marsee and Frick 2007; Miller and Lynam 2003) and thus there are shared method variance concerns. In addition, the sample was recruited from a pool of individuals attending college and therefore results cannot necessarily be extrapolated to all emerging adults (Arnett 2000). The assessment battery included standard self-report measures of psychopathic traits and personality disorder symptoms, but future investigations will likely benefit from more in-depth diagnostic interview assessments of these constructs. Related to this point, this study used the PDQ-4 to provide symptom counts for APD and BPD. The PDQ-4 is thought to be particularly useful as a screening tool for determining those personality disorders that merit further assessment (Bagby and Farvolden 2004). Furthermore, it has been used in non-clinical samples to provide information on personality disorder features from a dimensional (rather than categorical) perspective (Bagby and Farvolden 2004; Fossati et al. 2004; Huang et al. 2007). However, the unique associations revealed in this study would benefit from future work using structured diagnostic instruments. Given the sample size and exploratory nature of the current study, we felt it necessary to examine these personality disorder relations using brief self-report measures rather than an in-depth diagnostic interview. In order to gain a better understanding of the role of forms and functions of aggression in the development of personality pathology, future studies should employ prospective longitudinal designs. The direction of effect between aggressive subtypes and personality pathology is not clear. It is conceivable that aggressive behavior precedes personality pathology in emerging adulthood, but until long-term prospective developmental studies are conducted we must be cautious to not infer causality. Strengths of the study include the fact that the sample was quite large and multiple assessments were conducted to test the empirical questions.

Implications

The findings from this study suggest a number of implications and future research questions. We echo the call of others for interventions that target both forms and functions of aggression across development and the need for additional studies on this topic (Young et al. 2006). First, because reactive relational aggression has been found to be uniquely associated with hostile attribution biases (i.e., interpreting malicious intent in ambiguous provocation contexts) for relational provocation situations (Bailey and Ostrov in press; cf. Marsee and Frick 2007) and given the role that a hostile world view plays in BPD features (Geiger and Crick 2001), future research should test if hostile attribution biases for relational provocations mediate the association between reactive relational aggression and borderline personality disorder. Second, future studies should examine the association between borderline personality features and functions of relational aggression in earlier developmental periods. Third, future research should test if harsh and coercive parenting practices moderate the association between relational aggression and personality pathology. Past research has documented that specific types of aversive parental behavior are associated with an elevated risk for offspring borderline personality disorder in emerging adulthood (Johnson et al. 2006). Moreover, parents that use psychological control (e.g., love withdrawal or guilt induction) as a discipline strategy are more likely to have children who display relational aggression (e.g., Nelson et al. 2006). Thus, relational aggression may predict borderline personality disorder when children are exposed to high levels of aversive parenting and psychological control. Finally, more formal assessments of psychopathy that include an index of callous-unemotional traits (Frick et al. 2003, 2000), should be included in future research studies.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the study highlights the unique associations between relational aggression and personality pathology. That is, relational aggression was uniquely associated with borderline personality symptoms, whereas both function types of physical aggression and proactive relational aggression were associated with antisocial personality features. In addition, proactive physical aggression was associated with psychopathic tendencies. Collectively, this study highlights the differential associations between forms and functions of aggression and indices of personality pathology in typically developing emerging adults.

Notes

In selecting participants for the larger ERP study and the test–retest assessment, in order to increase variability in the sample, scheduling preference was given to participants who were above the mean on physical aggression, relational aggression or both. There were no statistically significant differences between the sub-sample that completed the second time point and those that did not for age [t(697) = 1.47, p = .143], academic year [t(699) = 1.14, p = .253] or GPA [t(518) = −1.50, p = .134]. There was also no difference for reactive relational aggression between those that participated at time 2 (M = 15.21; SD = 5.53) and those that did not (M = 14.64; SD = 5.33), t(698) = .90, p = .37. There were differences for proactive relational aggression, t(698) = 3.12, p = .002, such that those that completed time 2 (M = 10.35; SD = 4.57) were higher than those that did not (M = 8.94; SD = 3.68). The test–retest sub-sample (M = 5.50; SD = 2.99) was higher in proactive physical aggression than those that did not return to the laboratory (M = 4.90; SD = 2.50), t(698) = 1.98, p = .048. Finally, the test–retest sub-sample (M = 6.85; SD = 3.69) was higher in reactive physical aggression than those that did not return to the laboratory (M = 5.64; SD = 3.38), t(700) = 2.98, p = .003.

Due to missing data on the fearless dominance scale of the PPI for one participant the lower bound for the range was 26 and not 28.

Multicollinearity was not detected as the conditioning index was not greater than 30 for any of the dimensions and the variance proportions were not greater than .50 for more than two different variables (Tabachnick and Fidell 2007).

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text revision). Washington, DC: Author.

Arnett, J. J. (1994). Are college students adults? Their conceptions of the transition to adulthood. Journal of Adult Development, 1, 154–168.

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469–480.

Arnett, J. J., & Taber, S. (1994). Adolescence terminable and interminable: When does adolescence end? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 23, 517–537.

Bagby, R. M., & Farvolden, P. (2004). The personality diagnostic questionnaire-4 (PDQ-4). In M. J. Hilsenroth & D. L. Segal (Eds.), Comprehensive handbook of psychological assessment, vol. 2: Personality assessment. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Bailey, C. A., & Ostrov, J. M. (in press). Differentiating forms and functions of aggression in emerging adults: Associations with hostile attribution biases and normative beliefs. Journal of Youth and Adolescence.

Bandura, A. (1973). Aggression: A social learning analysis. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Barratt, E. S., Stanford, M. S., Dowdy, L., Liebman, M. J., & Kent, T. A. (1999). Impulsive and premeditated aggression: A factor analysis of self-reported acts. Psychiatry Research, 86, 163–174.

Barratt, E. S., Stanford, M. S., Felthous, A. R., & Kent, T. A. (1997a). The effects of phenytoin on impulsive and premeditated aggression: A controlled study. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 17, 341–349.

Barratt, E. S., Stanford, M. S., Kent, T. A., & Felthous, A. (1997). Neuropsychological and cognitive psychophysiological substrates of impulsive aggression. Biological Psychiatry, 41, 1045–1061.

Benning, S. D., Patrick, C. J., Hicks, B. M., Blonigen, D. M., & Krueger, R. F. (2003). Factor structure of the psychopathic personality inventory: Validity and implications for clinical assessment. Psychological Assessment, 15, 340–350.

Benning, S. D., Patrick, C. J., Salekin, R. T., & Leistico, A.-M. R. (2005). Convergent and discriminant validity of psychopathy factors assessed via self report: A comparison of three instruments. Assessment, 12, 270–289.

Berkowitz, L. (1963). Aggression: A social psychological analysis. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Bushman, B. J., & Anderson, C. A. (2001). Is it time to pull the plug on the hostile versus instrumental aggression dichotomy? Psychology Review, 108, 273–279.

Chabrol, H., Rousseau, A., Callahan, S., & Hyler, S. E. (2007). Frequency and structure of DSM-IV personality disorder traits in college students. Personality and Individual Differences, 43, 1767–1776.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, (2nd ed.). New York: Academic Press.

Conner, K. R., Houston, R. J., Sworts, L. M., & Meldrum, S. (2007) Reliability of the impulsive-premeditated aggression scale (IPAS) in treated opiate dependent individuals. Addictive Behaviors, 32, 655–659.

Cote, S. M., Vaillancourt, T., & LeBlanc, J. C. (2006). The development of physical aggression from toddlerhood to pre-adolescence: A nation wide longitudinal study of Canadian children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 34, 71–85.

Crick, N. R., & Dodge, K. A. (1996). Social information-processing mechanisms in reactive and proactive aggression. Child Development 67, 993–1002.

Crick, N. R., & Grotpeter, J. K. (1995). Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child Development, 66, 710–722.

Crick, N. R., Murray-Close, D., & Woods, K. A. (2005). Borderline personality features in childhood: A shorter-term longitudinal study. Development and Psychopathology, 17, 1051–1070.

Crick, N. R., Ostrov, J. M., & Kawabata, Y. (2007). Relational aggression and gender: An overview. In D. J. Flannery, A. T. Vazsonyi, & I. D. Waldman (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of violent behavior and aggression (pp. 245–259). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Day, D. M., Bream, L. A., & Pal, A. (1992). Proactive and reactive aggression: An analysis of subtypes based on teacher perceptions. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 21, 210–217.

Dodge, K. A. (1991). The structure and function of reactive and proactive aggression. In D. J. Pepler & K. H. Rubin (Eds.), The development and treatment of childhood aggression. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Dodge, K. A., & Coie, J. D. (1987). Social-information processing factors in reactive and proactive aggression in children’s peer groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 1146–1158.

Dodge, K. A., Coie, J. D., & Lynam, D. (2006). Aggression and antisocial behavior in youth. In W. Damon (Series Ed.), & N. Eisenberg (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., pp. 719–788). New York, NY: Wiley.

Fite, P. J., & Colder, C. R. (2007). Proactive and reactive aggression and peer delinquency: Implications for prevention and intervention. Journal of Early Adolescence, 27, 223–240.

Fite, P. J., Colder, C. R., & Pelham, W. E. Jr. (2006). A factor analytic approach to distinguish pure and co-occurring dimensions of proactive and reactive aggression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 35, 578–582.

Fite, P. J., Stauffacher, K., Ostrov, J. M., & Colder, C. (in press). Replication and extension of Little et al.’s (2003) forms and functions of aggression measure. International Journal of Behavioral Development.

Forouzan, E., & Cooke, D. J. (2005). Figuring out la femme fatale: Conceptual and assessment issues concerning psychopathy in females. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 23, 765–778.

Fossati, A., Barratt, E. S., Carretta, I., Leonardi, B., Grazioli, F., & Maffei, C. (2004) Predicting borderline and antisocial personality disorder features in nonclinical subjects using measures of impulsivity and aggressiveness. Psychiatry Research, 125, 161–170.

Frick, P. J., Bodin, S. D., & Barry, C. T. (2000). Psychopathic traits and conduct problems in a community and clinic-referred samples of children: Further development of the psychopathy screening device. Psychological Assessment, 12, 382–393.

Frick, P. J., Cornell, A. H., Barry, C. T., Bodin, S. D., & Dane, H. E. (2003). Callous-unemotional traits and conduct problems in the prediction of conduct problem severity, aggression, and self-report of delinquency. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 31, 457–470.

Galen, B. R., & Underwood, M. K. (1997). A developmental investigation of social aggression among children. Developmental Psychology, 33, 589–600.

Geiger, T., & Crick, N. R. (2001). A developmental psychopathology perspective on vulnerability to personality disorders. In R. Ingram & J. M. Price (Eds.), Vulnerability to psychopathology: Risk across the life span (pp. 57–102). New York: Guilford Press.

Goldstein, S. E., Chesir-Teran, D., & McFaul, A. (2008). Profiles and correlates of relational aggression in young adults’ romantic relationships. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37, 251–265.

Goldstein, S. E., Young, A., & Boyd, C. (in press). Relational aggression at school: Associations with school safety and social climiate. Journal of Youth and Adolescence.

Haden, S. C., Scarpa, A., & Stanford, M. S. (2007). Validation of the impulsive/premeditated aggression scale in college students; submitted for publication.

Hare, R. D. (1991). The hare psychopathy checklist—revised. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Multi-Health Systems.

Harpur, T. J., Hare, R. D., & Hakstian, A. R. (1989). Two-factor conceptualization of psychopathy: Construct validity and assessment implications. Psychological Assessment, 1, 6–17.

Houston, R. J., & Conner, K. R. (2006). Characterization of aggressive behavior in substance users: Preliminary findings [Abstract]. Presentation at the XVII World Meeting of the International Society for Research on Aggression, Minneapolis, MN.

Houston, R. J., & Stanford, M. S. (2006). Characterization of aggressive behavior and phenytoin response. Aggressive Behavior, 32, 38–43.

Houston, R. J., Stanford, M. S., Villemarette-Pittman, N. R., Conklin, S. M., & Helfritz, L. E. (2003). Neurobiological correlates and clinical implications of aggressive subtypes. Journal of Forensic Neuropsychology, 3, 67–87.

Huang, X., Ling, H., Yang, B., & Dou, G. (2007). Screening of personality disorders among Chinese college students by personality diagnostic questionnaire-4. Journal of Personality Disorders, 21, 448–454.

Hubbard, J. A., Dodge, K. A., Cillessen, A. H. N., Coie, J. D., & Schwartz, D. (2001). The dyadic nature of social information processing in boys’ reactive and proactive aggression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 268–80.

Hubbard, J. A., Parker, E. H., Ramsden, S. R., Flanagan, K. D., Relyea, N., Dearing, K., et al. (2004). The relations among observational, physiological, and self-report measures of children’s anger. Social Development, 13, 14–39.

Hubbard, J. A., Smithmyer, C. M., Ramsden, S. R., Parker, E. H., Flanagan, K. D., Dearing, K. F., et al. (2002). Observational, physiological, and self-report measures of children’s anger: Relations to reactive versus proactive aggression. Child Development, 73, 1101–1118.

Hunt, M. K., Hopko, D. R., Bare, R., Lejuez, C. W., & Robinson, E. V. (2005). Construct validity of the balloon analog risk task (BART): Associations with psychopathy and impulsivity. Assessment, 12, 416–428.

Hyler, S. E. (2003). Personality diagnostic questionnaire, version 4. New York, NY: Human Informatics.

Hyler, S. E., Skodol, A. E., Kellman, D., Oldham, J. M., & Rosnick, L. (1990). Validity of the personality diagnostic questionnaire-revised: Comparison with two structured interviews. American Journal of Psychiatry, 147, 1043–1048.

Johnson, J. G., Cohen, P., Chen, H., Kasen, S., & Brook, J. S. (2006). Parenting behaviors associated with risk for offspring personality disorder during adulthood. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63, 579–587.

Kimonis, E. R., Frick, P. J., Fazekas, H., & Loney, B. R. (2006). Psychopathy, aggression, and the processing of emotional stimuli in non-referred girls and boys. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 24, 21–37.

Kline, R. B. (1998). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press.

Kockler, T. R., Stanford, M. S., Nelson, C. E., Meloy, J. R., & Sanford, K. (2006). Characterizing aggressive behavior in a forensic population. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 76, 80–85.

Lagerspetz, K. M. J., Björkqvist, K., & Peltonen, T. (1988). Is indirect aggression more typical of females? Gender differences in aggressiveness in 11- to 12-year-old children. Aggressive Behavior, 14, 403–414.

Lento-Zwolinski, J. (2007). College students’ self-report of psychosocial factors in reactive forms of relational and physical aggression. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 24, 407–421.

Lilienfeld, S. O., & Andrews, B. P. (1996). Development and preliminary validation of a self-report measure of psychopathic personality traits in noncriminal populations. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66, 488–524.

Linder, J. R., Crick, N. R., & Collins, W. A. (2002). Relational aggression and victimization in young adults’ romantic relationships: Associations with perceptions of parent, peer, and romantic relationship quality. Social Development, 11, 69–86.

Little, T. D., Jones, S. M., Henrich, C. C., & Hawley, P. H. (2003). Disentangling the “whys” from the “whats” of aggressive behavior. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 27, 122–183.

Loudin, J. L., Loukas, A., & Robinson, S. (2003). Relational aggression in college students: Examining the roles of social anxiety and empathy. Aggressive Behavior, 29, 430–439.

Marsee, M. A., & Frick, P. J. (2007). Exploring the cognitive and emotional correlates to proactive and reactive aggression in a sample of detained girls. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 35, 969–981.

Mathias, C. W., Stanford, M. S., Marsh, D. M., Frick, P. J., Moeller, F. G., Swann, A. C., et al. (2007). Characterizing aggressive behavior with the impulsive/premeditated aggression scale among adolescents with conduct disorder. Psychiatry Research, 151, 231–242.

McHoskey, J. W. (2001). Machiavellianism and personality dysfunction. Personality and Individual Differences, 31, 791–798.

Miller, J. D., & Lynam, D. R. (2003). Psychopathy and the five-factor model of personality: A replication and extension. Journal of Personality Assessment, 81, 168–178.

Moffitt, T. E. (1993). Adolescent-limited and life-course persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review, 100, 674–701.

Morales, J. R., & Crick, N. R. (1998). Self-report measure of aggression and victimization. Unpublished measure. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota.

Murray-Close, D., Ostrov, J. M., Nelson, D. A., Crick, N. R., & Coccaro, E. F. (2008). Proactive, reactive and romantic relational aggression in adulthood: Measurement, predictive validity, and gender differences; submitted for publication.

Nelson, L. J., Badger, S., & Wu, B. (2004). The influence of culture in emerging adulthood: Perspectives of Chinese college students. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 28, 26–36.

Nelson, D. A., Hart, C. H., Yang, C., Olsen, J. A., & Jin, S. (2006). Aversive parenting in China: Associations with child physical and relational aggression. Child Development, 77, 554–572.

Nelson, L. J., Padilla-Walker, Carroll, J. S., Madsen, S. D., Barry, C. M., & Badger, S. (2007). “If you want me to treat you like an adult, start acting like one!” comparing the criteria that emerging adults and their parents have for adulthood. Journal of Family Psychology, 21, 665–674.

NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. (2004). Trajectories of physical aggression from Toddlerhood to middle childhood. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 69, (Serial No. 278).

Ostrov, J. M. (2006). Deception and subtypes of aggression in early childhood. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 93, 322–336.

Ostrov, J. M., & Crick, N. R. (2007). Forms and functions of aggression during early childhood: A short-term longitudinal study. School Psychology Review, 36, 22–43.

Poulin, F., & Boivin., M. (2000). Reactive and proactive aggression: Evidence of a two-factor model. Psychological Assessment, 12, 115–122.

Price, J. M., & Dodge, K. A. (1989). Reactive and proactive aggression in childhood: Relations to peer status and social context dimensions. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 17, 455–71.

Prinstein, M. J., & Cillessen, A. H. N. (2003). Forms and functions of adolescent peer aggression associated with high levels of peer status. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 49, 310–342.

Pulkkinen, L. (1996). Proactive and reactive aggression in early adolescence as precursors to anti- and prosocial behaviors in young adults. Aggressive Behavior, 22, 241–257.

Raine, A., Dodge, K., Loeber, R., Gatzke-Kopp, L., Lynam, D., Reynolds, C., et al. (2006). The reactive-proactive aggression questionnaire: Differential correlates of reactive and proactive aggression in adolescent boys. Aggressive Behavior, 32, 159–171.

Raine, A., Meloy, J. R., Bihrle, S., Stoddard, J., LaCasse, L., & Buchsbaum, M. S. (1998). Reduced prefrontal and increased subcortical brain functioning assessed using positron emission tomography in predatory and affective murderers. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 16, 319–332.

Schad, M. M., Szwedo, D. E., Antonishak, J., Hare, A., & Allen, J. P. (2008). The broader context of relational aggression in adolescent romantic relationships: Predictions from peer pressure and links to psychosocial functioning. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37, 346–358.

Schwartz, D., McFadyen-Ketchum, S. A., Dodge, K. A., Pettit, G. S., & Bates, J. E. (1998). Peer group victimization as a predictor of children’s behavior problems at home and in school. Development and Psychopathology, 10, 87–99.

Spear, L. P. (2000). Neurobehavioral changes in adolescence. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 9, 111–114.

Stanford, M. S., Greve, K. W., & Gerstle, J. E. (1997). Neuropsychological correlates of self-reported impulsive aggression in a college sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 23, 961–965.

Stanford, M. S., Houston, R. J., Mathias, C. W., Villemarette-Pittman, N. R., Helfritz, L. E., & Conklin, S. M. (2003). Characterizing aggressive behavior. Assessment, 10, 183–90.

Stanford, M. S., Houston, R. J., Villemarette-Pittman, N. R., & Greve, K. W. (2003). Premeditated aggression: Clinical assessment and cognitive psychophysiology. Personality and Individual Differences, 34, 773–781.

Storch, E. A., & Masia-Warner, C. (2004). The relationship of peer victimization to Social anxiety and loneliness in adolescent females. Journal of Adolescence, 27, 351–362.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Boston: Pearson Press.

van Dulmen, M. H. M., Goncy, E. A., Haydon, K. C., & Collins, W. A. (2008). Distinctiveness of adolescent and emerging adult romantic relationship features in predicting externalizing behavior problems. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37, 336–345.

Vitaro, F., Gendreau, P. L., Tremblay, R. E., & Oligny, P. (1998). Reactive and proactive aggression differentially predict later conduct problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 39, 377–385.

Waschbusch, D. A., Pelham, W. E., Jennings, J. R., Greiner, A. R., Tarter, R. E., & Moss, H. B. (2002). Reactive aggression in boys with disruptive behavior disorders: Behavior, physiology and affect. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 30, 641–656.

Werner, N. E., Crick, N. R. (1999). Relational aggression and social-psychological adjustment in a college sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 108, 615–623.

Werner, N. E., & Nixon, C. L. (2005). Normative beliefs and relational aggression: An investigation of the cognitive bases of adolescent aggressive behavior. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34, 229–243.

Wilson, D. L., Frick, P. J., & Clements, C. B. (1999). Gender, somatization and psychopathic traits in a college sample. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 21, 221–235.

Woodworth, M., & Porter, S. (2002). In cold blood: Characteristics of criminal homicides as a function of psychopathy. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111, 436–445.

Young, E. L., Boye, A. E., & Nelson, D. A. (2006). Relational aggression: Understanding, identifying and responding in schools. Psychology in the Schools, 43, 297–312.

Zalecki, C. A., & Hinshaw, S. P. (2004). Overt and relational aggression in girls with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33, 125–137.

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Geiger, T. C., & Crick, N. R. (2005). Relational and physical aggression, prosocial behavior, and peer relations: Gender moderation and bidirectional associations. Journal of Early Adolescence, 25, 421–452.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the members of the UB Social Development, Social Cognition and Neuroscience Project. In particular, we thank Stephanie A. Godleski, Emily E. Ries and Nicolas Schlienz for their assistance with the coordination of this project. We wish to acknowledge the participants for volunteering for this study. Portions of this study were presented at: The 47th annual meeting of the Society for Psychophysiological Research, Savannah, GA; the 2007 meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, Boston, MA; the 46th annual meeting of the Society for Psychophysiological Research, Vancouver, British Columbia; and the 2008 meeting of the Society for Research on Adolescence, Chicago, IL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ostrov, J.M., Houston, R.J. The Utility of Forms and Functions of Aggression in Emerging Adulthood: Association with Personality Disorder Symptomatology. J Youth Adolescence 37, 1147–1158 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-008-9289-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-008-9289-4