Abstract

Theory on nomadic political complexity has largely been based on twentieth century ethnography and numerous historical accounts of the military confederations of pastoral nomads. Over the past two decades, archaeologists have increasingly used material evidence to evaluate ideas about nomadic polities and have added indigenous and local-scale perspectives to an understanding of nomadic political process in many regions across the Old World. One of these is Mongolia, a major center of nomadic state and empire formation, where archaeologists have recently focused attention on an early regional polity that arose at the end of the first millennium BC and is known as the Xiongnu (also Hsiung-nu) state. This paper synthesizes the latest archaeological research on the Xiongnu state in order to evaluate historical models that explain state emergence among nomads on the far eastern steppe. The material record from Mongolia adds the detail and resolution needed to refine existing explanations for Xiongnu state emergence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The distant predecessors of today’s Mongolians constructed some of the great polities of the Old World. From the late first millennium BC onwards, eastern Eurasian steppe groups began organizing large-scale states with names like Xiongnu, Turk, and Uighur, whose history is known primarily through the lens of Chinese accounts but also from texts written by steppe peoples themselves (Rogers 2012). These expansive polities became a defining feature of Eurasian history, and certainly the best known example is the Mongolian empire founded by Genghis Khan in the thirteenth century (Fitzhugh et al. 2009). The sheer immensity of the Mongolian empire and its cultural, political, and economic repercussions have long challenged scholars to explain how a relatively obscure group of steppe nomads managed to conquer and rule such a substantial swathe of the Old World. The answers to this question lie in the cultural character of the eastern steppe region, its economy and organization, and its long history and prehistory of sophisticated politics.

Despite the prominent role of East Asian nomadic states and empires on the world stage, surprisingly little is known of the indigenous political traditions that gave rise to them (Rogers 2007; Frachetti 2008; Hanks 2010). Steppe polities emerged from a setting of extensive agro-pastoralism, mobile populations, strongly independent local groups, and marginal environments—features commonly associated with more egalitarian societies (Salzman 2004, pp. 68–69). How and why regionally complex organizations emerged among nomadic peoples is one of the foremost research questions in Mongolian archaeology today. To better explore the political prehistory of the eastern steppe, a region extending from eastern Kazakhstan to western Manchuria with Mongolia as its center, recent archaeological research has focused on the genesis of these nomadic states and empires. Over the past two decades, Mongolian and international archaeologists have pursued intensive study of the initial nomadic polity in this historical sequence—a polity known as the Xiongnu confederation (c. third century BC), and argued to be the first nomadic state in East Asia.

By the end of the first millennium BC, references appear in Chinese historical documents to devastating conflicts with a regionally integrated and militarily powerful political group to the north of Chinese territory known as the ‘Xiongnu’ (Watson 1993). Based on these historical texts, this polity was populated primarily by horse-riding pastoral nomads against whom the Qin Empire (221–207 BC) and later the Han Dynasty (202 BC—AD 220) supposedly erected major sections of the Great Wall (Di Cosmo 2006). The historical image of the early Xiongnu polity in early China was the standard steppe nomad one: a warlike people causing frontier havoc. The Xiongnu state is historically dated from 209 BC to AD 150; at its height, Xiongnu territory stretched from Manchuria to the Altai mountains and easternmost Kazakhstan, and from southern Siberia to Inner Mongolia. Chinese histories are the major source of information concerning the society, culture, and politics of the Xiongnu; however, the emergence of this political group and its regional organization remain substantial questions for both historians and anthropologists (Kradin 2001, pp. 201–210).

From an anthropological perspective, a nomadic state has typically been viewed as something of an anomaly. The vast majority of anthropological and historical research on nomadic politics supports a particular view of the organizational potential of mobile herders. Because of their mobility, lack of surplus, fierce independence, and in many cases their armed capacity to resist, nomads tend not to form complex polities (Salzman 2004, pp. 98–101; Kürsat-Ahlers 1996; Irons 1979). Large-scale organization among nomadic peoples, if it occurs at all, is viewed as an unstable condition with little genuine integration. Consequently, many anthropologists and historians explain the rise of nomadic polities as a response to disruption and warfare or as a result of the need for structured relations with neighboring agricultural states (Franz 2005; Paul 2003; Salzman 2000; Khazanov 1994). Although there has been some diversity of opinion over the decades (e.g. Lattimore 1940), the latest explanations for the Xiongnu polity draw upon this combined body of anthropological theory and historical information to make a case for a state formation process based on widespread and transformative conflict. According to these models, the Xiongnu state arose from a process of (1) destabilization involving warfare and conquest; (2) substantial military success on the part of one group leading to the unequal incorporation of other groups and enhanced prestige for successful leaders, and (3) a transformation of military hierarchy into political authority and regional organization (Barfield 2001a, pp. 13–14; Di Cosmo 2002, pp. 174–190; Kradin 2011, pp. 78–83).

The militarism of some pre-modern nomads was certainly a phenomenon that influenced the politics and organization of many nomadic groups, and was an important variable in the Xiongnu case as well. Given anthropological expectations for local group autonomy and little in the way of regional political process, warfare as a primary mover is a tempting explanation, but it is not the only or necessarily the best one. Archaeological research on ancient nomadic polities in other parts of the Old World, particularly in Greater Mesopotamia on the Elamite and Amorite polities (third and second millennium BC), suggests that military prowess and conflict were important but subsidiary factors among many others that contributed to nomadic statehood (Porter 2012; Alizadeh 2010). Although the Mesopotamian setting was quite different from that of the eastern steppe, these case studies encourage greater attention to the variability of nomadic societies and a more nuanced and contextualized approach to explanations of socio-political process.

Moving beyond the received wisdom from ethnographic and historical studies, archaeologists working in eastern Eurasia have begun to devise novel and innovative theory based on the indigenous material record of early nomadic groups to explain socio-political process (Frachetti 2012; Chang 2012; Houle 2009; Shelach 2009a). Inspired by these trends, the present study evaluates theory on Xiongnu statehood by employing archaeological results from Mongolia to test current models for state formation in eastern Eurasia. Because the archaeology of the steppe zone warrants greater exposure in anthropological circles, I provide a fairly detailed introduction to Xiongnu archaeology as known from Mongolia. I include overviews of pertinent historical information on the rise of the Xiongnu state and a description of the relevant archaeological record as well as the latest research results. I then focus closely on what the material record reveals about the role of warfare and conquest as opposed to other processes of social and political consolidation. Based on perspectives arising from local area survey and excavation, I argue that current explanations cannot account for the timeline and sequence of changes associated with the process of early nomadic state formation. In response, I offer some alternative ideas that are more pertinent to the evidence derived from the material record.

Documenting the Xiongnu State: Nomads in History

Both archaeology and historical sources provide valuable evidence for the Xiongnu polity. These sources tell us that in addition to a population of mostly nomadic peoples, the state controlled a large geographical territory, exercised a powerful military capability, and maintained extensive networks of long-distance relationships (Watson 1993, pp. 135–137; Di Cosmo 2002, pp. 176–178). Statecraft innovated during the period of the Xiongnu state was re-used and modified by subsequent steppe polities, including the Mongol empire (Sneath 2006); and, therefore, this early period represents a critical watershed in East Asian political history. The search for evidence about the Xiongnu state has traditionally taken researchers to textual records; however, such evidence is not without its own unique problems. Both the known documents and controversies over ways to combine the textual and material records continue to pose conceptual and methodological problems for archaeologists working on Xiongnu statehood.

Four political periods in the history of ancient China were contemporary with the textually known Xiongnu polity: the Qin Empire (221–207 BC); the Western Han (202 BC–8 AD); the Xin (9–23 AD); and the Eastern Han (25–220 AD). While early Chinese records are based on a dynastic model which gives an impression of a single group wielding power for centuries, most dynasties were in fact heterogeneous in terms of who actually held political authority (Hansen 2000, pp. 5–6). The Xiongnu polity was likewise a dynamic and changing organization, with major re-organizations during its textually assessed chronological extent of about 350 years. Despite many problems in assessing the textual sources, archaeologists working on this period in the northern steppe zone are extremely fortunate to have historical accounts of the early nomads as seen through the eyes of state historians in the heartland of China.

The major textual sources containing information on Xiongnu society are the Shiji (c. 100 BC), the Hanshu (c. 36–116 AD), and the Hou Hanshu (c. 435 AD). There are also several minor sources and more recently discovered texts with important information, such as the Dunhuang wooden documents (Giele 2011). Of the major sources, only the first two were created by authors contemporary with the Xiongnu polity; the information provided by the Shiji text, authored by Sima Qian (c. 140–86 BC), is closest in time to the emergence of the nomadic polity. The Shiji text was recorded when the Xiongnu state was relatively mature and when the Han Dynasty and their nomadic neighbors were in the midst of an intensive period of warfare sustained over several decades.

What the Shiji author knew about the Xiongnu to the north, how he knew it, and how he chose to report his cultural and political insights are the kind of questions that make the work of deciphering ancient histories exceedingly difficult. However, current scholarship on Han Dynasty representations of the Xiongnu has made significant progress in assessing and answering such questions (e.g. Di Cosmo 2002; Goldin 2011; Miller 2011a). The Shiji descriptions of the Xiongnu are likely to have been based on earlier textual sources, contemporary interviews with individuals with frontier experience, the author’s own travels as well as his father’s historical notes, and common knowledge within the Han court (Di Cosmo 2002, pp. 267–270). Among the limitations of this account are unavoidable deficiencies in information, as well as textual reporting that was subject to cultural misunderstandings, bias, and rather extreme internal political agendas (Chin 2010).

There is an added problem in the Shiji in that the text likely projects backwards in time. In order to describe the earliest form of Xiongnu statehood a century earlier, Sima Qian extrapolates from the Xiongnu culture, organization, and frontier relationships of his own day (Di Cosmo 2002, p. 142). In short, the Shiji is a remarkable asset for understanding the eastern steppe past, but it is one that must be understood as a textual representation of a distant group by cultural outsiders, created during a time of conflict (Wells 2001, pp. 30–31). Moreover, as a document composed under the auspices of the Han state administration, the text was influenced by both the personal interests of Sima Qian and the views of the court elite at that time (Hardy 1994, pp. 58–60).

In spite of its limitations, however, the Shiji relates critical information, including the earliest account of Xiongnu state emergence and a detailed description of Xiongnu political structure. In Chapter 110, Sima Qian provides a description of the Xiongnu state as a large-scale, socially stratified, and centrally integrated organization (Watson 1993, pp. 136–137). It was led by a hereditary elite, which consisted of a single ruling house and three consort clans that provided senior marriage partners to members of the ruling house. Only members of these corporate groups were eligible for the highest political offices, which combined political authority, divine right, military leadership, and elite endogamy (Di Cosmo 2002, pp. 176–178). The Shiji text describes a great many offices that supported rulership, as well as a military-administrative decimal system of positions based on the number of horsemen a leader was responsible for mobilizing (e.g. 10, 100, 1,000, or 10,000), although there is some debate over the specificity of these actual counts (Kradin 2001, p. 208). Geographically, the polity was organized into a central section and eastern and western sections called the ‘left’ and ‘right’ kingships respectively. The ruler of the polity, known as the ‘Shanyu’, and his royal court directly controlled the central district, while the kingships on the left and right were positions appointed by the Shanyu from among male members of the royal family.

In addition, the Shiji text contains the earliest account of the formation of Xiongnu political and military power under the steppe leader Maodun (also transliterated as Modu, Mode, or Modun) (Watson 1993, pp. 134–136). According to Nicola Di Cosmo’s in-depth analysis of the Shiji text, this process began in 215 BC during a period of crisis on the steppe caused by Qin Dynasty expansion into the northern pasturelands of the Ordos loop region (including parts of Inner Mongolia, Ningxia, Shaanxi, and Gansu) (Fig. 1), an area reported to have been the homeland of the textual Xiongnu (Di Cosmo 2002, pp. 174–176; Watson 1993, p. 133). As recounted by Sima Qian, Maodun was a member of an existing elite lineage but had been barred from attaining the highest political positions. He usurped power by innovating new military techniques and organization, assassinated his father to acquire a position of leadership, and then rapidly expanded militarily against neighboring groups (Watson 1993, pp. 135–136). While the sources and reliability of this account are not certain (Kradin 2001, pp. 47–55), this narrative of state formation has been taken quite literally with regards to its reported timing, process, and geography (Di Cosmo 2002, pp. 178–186).

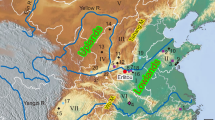

Map of the eastern Eurasian steppe zone and major sites of Xiongnu period archaeology. Detailed case-studies: 1 Egiin Gol; 2 Baga Gazaryn Chuluu. Cemeteries with elite burials: 3 Il’movaia Pad’; 4 Tsaram; 5 Gol Mod I; 6 Gol Mod II; 7 Noyon Uul; 8 Duurlig Nars; 9 Takhiltyn Khotgor. Cemetery sites: 10 Dyrestui; 11 Khudgiin Tolgoi; 12 Tamiryn Ulaan Khoshuu; 13 Shumbuuziin Belchir; 14 Ukhaa Khudag; 15 Maoqingguo; 16 Xigoupan; 17 Taohongbala; 18 Hulusitai; 19 Aluchaideng; 22 Ivolga cemetery. Settlements and craft centers: 20 Boroogiin Suurin; 21 Ivolga; 22 Bayan Under; 23 Tereljiin Dorvoljin; 24 Khustyn Bulag; 25 Khanui valley (Map: William Honeychurch)

Such valuable descriptions as these require close attention on the part of both historians and archaeologists; and, accordingly, there has been much discussion as to the proper relationship between the historical and material records (Brosseder and Miller 2011, pp. 30–31; Di Cosmo 2011, p. 38). There are two pertinent questions. First, what is the methodological relation between texts and archaeology? And second, how do we know that the association of a material culture with the textual Xiongnu is in fact appropriate? The first question has been explored extensively in the context of East, South, and Southeast Asian archaeology. ‘Source-side criticism’, advocated by Miriam Stark and others (Stark 2006a, b, pp. 315–319; Stark and Allen 1998; Wylie 1985), is one coherent and practical approach to this enduring problem in research methodology.

The source-side method views material and textual records as analytically distinct perspectives on the past and entirely different in character and resolution. Each record has unique problems and incompleteness and, therefore, each must be assessed independently in order to understand informational limitations prior to combining the two. Combination does not conflate the two records, but rather joins them through hypothesis and the development of testable expectations, followed by testing back and forth. In this stepwise manner, the two records bring their unique perspectives to bear differentially upon questions of social process, practices, and transformation in the past. Versions of this approach have already been explicitly advocated in Xiongnu archaeology (Miller 2009, pp. 34–39); and, in fact, most archaeology in Mongolia proceeds through these steps with various degrees of formality.

The second question concerns linking textual statements about ‘the Xiongnu’ to a particular material culture. We do not know precisely what Han Dynasty peoples understood by the name ‘Xiongnu’, and the term is now used in different ways and often lacks precise reference (Giele 2011, p. 75; Goldin 2011, pp. 226–228). However, one point is entirely clear: that it describes a northern, large-scale, highly organized political entity against which the Han Dynasty struggled for more than three centuries (Goldin 2011, p. 227). If, as in the present study, the objective is to analyze processes of regional-scale political complexity somewhere to the north of the Qin and Han Dynasty territories, then the material record of Mongolia is the most logical candidate (Rudenko 1962; Konovalov 1976; Tseveendorj 1985; Minyaev 1998; Honeychurch and Amartuvshin 2006a; Holotová-Szinek 2011). As I will argue below, there is no other northern area besides Mongolia that possesses material patterns for large-scale complex organization over an extended period contemporary with the Qin and Han states. For the purpose of this discussion, the definition of ‘Xiongnu’ is an organizational one and not related to a particular ethnic, linguistic, or tribal group as is often assumed in much historical and some archaeological research (Hanks 2002, pp. 184–185; Miller 2009, p. 9).

Eastern Eurasia and the Precedents of Nomadic Complexity

The eastern steppe region can be defined in various ways and is often synonymous with the ‘Inner Asia’ of Owen Lattimore’s famous historical and geographic analysis (Lattimore 1940). I will focus on the core of the eastern steppe, the present-day territory of Mongolia, but will draw as well on data and ideas arising from archaeological work in southern Siberia and northern and western sections of what is today China (Fig. 1). The environmental zones across this expansive macro-region are extremely diverse and consist of more than just steppe lands. As I have defined it, eastern Eurasia ranges from dense coniferous forests in the north through gradations of forest-steppe and open grassland to arid steppe and the Gobi Desert in the south. Across the Gobi, and moving further southwards, grasslands resume and are transitional to the mountains, river valleys and the cultural heartland of China, known as the Central Plain region.

From east to west, environmental changes are again vegetational but linked more to topography. Moving westward from the forested mountains of Manchuria, broad rolling plains make up most of eastern Inner Mongolia and eastern Mongolia. These classic steppe lands of the east are intersected by the north-central Khentii and Khangai mountain ranges in central Mongolia, and this central region of low mountains and intermontane steppe also holds the major river basins which mostly flow northward to the Arctic. Further to the west, there are arid flatlands, salt lakes, and the foothills of the high Altai mountains. This impressive mountain range overlaps the borders of four countries, linking the westernmost portions of Mongolia to Siberia, Kazakhstan, and Xinjiang (Fig. 1).

The diversity of these environments suggests great differences and potentials in subsistence practices, movement regimes, and productive risk. Seasonal herding of sheep and goats, cattle, camels, horses, yaks, and in some places, reindeer, are all part of the pastoral tradition of the eastern steppe. Although evidence is still limited, domestic herd animals were probably introduced during the late third and early second millennium BC in different parts of Mongolia, and perhaps earliest in the west and northwest (Kovalev and Erdenebaatar 2009, pp. 150–152; Honeychurch and Wright 2008). Pastoralism was part of a broader set of productive strategies that included small-scale agriculture, hunting, gathering, and fishing where these pursuits were viable (Honeychurch and Amartuvshin 2007; Machicek 2011).

Late Bronze Age Monuments and Lifeways (1400–800 BC)

The two pertinent periods preceding the rise of the Xiongnu state are the Late Bronze (1400/1300–800 BC) and Early Iron Age (800–300 BC). The transition from the second to first millennium BC in Mongolia marks changes in material culture suggesting new ways of expressing status and identity, greater involvement in interregional exchange and alliance networks, and the growth of political centers. The most impressive sites in Mongolia of these periods are becoming better known internationally but they still sit in the shadow of much more famous sites like Arzhan in Tuva, Issyk in southeastern Kazakhstan, and the Pazyryk cemeteries of Altai. For that reason, I concentrate on what is known from the Mongolian record while attempting to contextualize these patterns in terms of the broader macro-region.

While the evidence is still far from robust, the first suggestions of social differentiation and inequality appear in Mongolia around the mid to late second millennium BC. The sites demonstrating these patterns are impressive mounded stone monuments and burials known in Mongolian as khirigsuur and dating between 1500/1400 and 800 BC, based on a growing array of radiocarbon analyses (Littleton et al. 2012; Fitzhugh 2009; Wright 2007; Erdenebaatar 2002). Khirigsuur monuments are large stone mounds within rectangular or circular stone enclosures, beyond which are ‘satellite’ features in the form of multiple small stone piles. The central mound is constructed of rocks piled systematically, often around an internal cist made of large slabs with a cap stone. Human skeletal remains are consistently recovered from these cists in the western regions of Mongolia, while in central and east-central regions internal cists do not, as of yet, show much evidence of such remains. The satellite features sometimes contain horse crania, vertebrae, and hoof cores, which are thought to be remnants of horse sacrifices and feasting events associated with monument building. These monuments rarely include artifacts as part of the original construction event, though subsequent millennia of re-use have usually left substantial intrusive artifact deposits.

Khirigsuurs are related to the central Eurasian tradition of building stone or earthen kurgan mortuary mounds and they have similarities with burial constructions in the Altai-Sayan region, Minusinsk, Tuva, and perhaps as far east as Manchuria, though further work is needed on their variability and dating. Currently, khirigsuurs are reported from western and central Mongolia and the Transbaikal region of southern Siberia, down to the south Gobi and in eastern Mongolian provinces, but in declining numbers. The wide variation in size and complexity of khirigsuur mounds may indicate differences in corporate or community wealth and regional standing (Wright 2007), or in individual status and leadership (Frohlich et al. 2009). Even though these monuments do not contain grave goods, the labor needed to build most of them was significant. Khirigsuurs appear as single features or in large multi-feature complexes, sometimes accompanied by a somewhat better known monumental type from Mongolia, the deer stone stela. Deer stones are found in western, central and central-east Mongolia, as well as in Altai, Tuva, and Buryatia, and consist of a four-sided dressed stone up to 2.5 m in height,with elaborate pecked images of stylized deer, belts with hanging weapons and re-curved bows, and, at the top, circular designs or, occasionally, a human face (Fig. 2). One interpretation is that deer stone monuments are anthropomorphic representations depicting the head, deer tattooed body, and weapons of a high status individual (Fitzhugh 2009). Like khirigsuur satellite features, deer stones are surrounded by interred horse skulls, and radiocarbon dates from these contexts suggest a construction period overlapping that of khirigsuurs, between 1100 and 750 BC. A few of the most impressive khirigsuur-deer stone complexes are: Uushigiin Ovor in the Khovsgol province, northwest Mongolia (Takahama et al. 2006); the Shurgakhyn Am khirigsuur of Zavkhan province in western Mongolia (67 m diameter) (Amartuvshin and Jargalan 2007, p. 2); and the Shiebar-kul/Sanhaizi khirigsuur site in northern Xinjiang (60 m diameter, 20 m height) (Hatakeyama 2002).

The proposed change towards greater inequality among individuals or between sub-regional groups, as represented by these monumental and ceremonial sites, has been explained with reference to a number of different variables. These include climatic aridity followed by group migration, warfare, and conquest (Tsybiktarov 2003; Erdenebaatar 2004), and elite aggrandizement through feasting and ceremonialism (Allard and Erdenebaatar 2005; Houle 2010). Beyond the practice of monument making, little is known about the lifeways of the builders of these impressive sites. The latest data come from recent excavations of Late Bronze Age habitations in central Mongolia (Houle 2010); isotopic and paleopathological analyses of bone samples from khirigsuur excavations (Machicek 2011); and comparisons with the contemporary and much better-known Karasuk culture in the Minusinsk Basin northeast of Mongolia (Legrand 2006). Together these provide a picture of small-scale community groups with pastoral or mixed agro-pastoral adaptations following limited mobility regimes between river valleys and associated uplands.

Although the famous bronze weapons and toolsets associated with Karasuk sites are not found in khirigsuur complexes, they are unmistakably represented on deer stones and have been recovered from other contemporary contexts in Mongolia (Park et al. 2011, p. 814). Such connections between regions were probably facilitated by the novel technology of horseback riding, which was likely practiced in Mongolia by the mid to late second millennium BC (Honeychurch et al. 2009). The widespread extent of khirigsuur monuments and their similarities with other kurgan building and burial cultures as far away as southern Xinjiang (Wagner et al. 2011) all hint at a multi-regional cultural exchange network that archaeologists have posited for eastern Eurasia as early as the Middle Bronze Age, if not earlier (Frachetti 2012).

Early Iron Age Transitions to Complex Societies (800–300 BC)

Throughout the early to later mid first millennium BC, regional cultural dynamics were driven by increased access to horses and rapid mobility, intra-steppe interactions, and greater interchange with state societies on the periphery of the Eurasian grasslands. Political relationships likely involved shifts to more formalized political hierarchies, longer distance alliance-building, and prestige gifting between steppe elites. How and why these socio-political transformations towards institutional inequality and factional leadership occurred among steppe peoples is still poorly understood, though the material indications of these changes are pervasive and most clearly demonstrated by transformations in mortuary and monumental site patterns. Evidence from Mongolia and surrounding regions suggests that by 800/900 BC burial practices overall became more elaborate and began to include greater assemblages of exotic and costly items (Derevyanko and Molodin 2000, Chugunov et al. 2004; Tseveendorj et al. 2007; Honeychurch et al. 2009). These valued items, and in particular long distance prestige goods, were important for negotiating local relationships of loyalty and leadership and began to figure prominently in funeral ceremonies involving conspicuous deposition of wealth.

Perhaps the best example of these new practices comes from the well-known ‘royal’ kurgan excavations at the site of Arzhan in the Uyuk Basin of Tuva (Gryaznov 1980). The Arzhan 1 kurgan is dated to c. 800 BC and represents a monumental interment of two primary elite individuals whose burial assemblage so far has no contemporary match within the broader region. The kurgan itself is a circular stone mound 120 m across and 4 m high, with a complex internal timber construction dividing the feature into 70 distinct sections. Excavations have revealed a pillaged central burial chamber with elaborate log coffins associated with the two elite occupants. Positioned around them were 160 harnessed riding horses, a number of accompanying human interments described as ‘attendants’, bronze weapons and tools, relatively early iron implements, items of personal adornment in gold and turquoise, examples of Scytho–Siberian ‘animal style’ decorative bronzes, and fragments of deer stones. Recent work in the surrounding multi-kurgan landscape has resulted in the discovery and excavation of the Arzhan 2 kurgan, dating to the seventh century BC, which confirms the continued use of the area for mortuary rituals connected with the uppermost elite individuals. The presence at Arzhan 2 of many items with material connections to Kazakhstan far to the west may help to explain the prominence of this region early on as a major corridor of travel through the Sayan–Altai mountains following the basin and tributaries of the Yenisei River (Chugunov et al. 2004, p. 6).

While Arzhan 1 and 2 are highly distinctive contexts, they are representative of a more general, though less grandiose, trend in mortuary practices during the Early Iron Age towards exclusivity, wealth, and imported materials. A more modest example of this trend in Mongolia is the emergence and spread of slab burial culture, beginning at c. 1000/900 BC (Volkov 1967; Tsybiktarov 1998; Erdenebaatar 2004). Slab burials display more consistent evidence for human interment than do Late Bronze Age khirigsuur monuments. They were constructed of medium to very large stone slabs, positioned on edge to create a rectangular enclosure around a central burial pit up to 1.8 m in depth and oriented to the east. The lengths of these stone enclosures are usually in the range 1.5–3 m, though many are in excess of 10 m, with slabs standing up to 2 m above the surface.

In addition to human interments, slab burials contain animal remains (horse bones are among the most common) and a wide range of artifacts, including bronze, stone, ceramic, and bone items, which are all usually found in disrupted contexts (Dikov 1958, p. 57). These mortuary features appear individually or in small to medium-sized groups, ordinarily of around 3–20 monuments. Cemeteries with the most impressive slab burials are generally in Mongolia’s eastern provinces, where for example the newly discovered site of Tsagaan Uul in the east Gobi Desert, with more than 200 such graves, indicates the prominence of these sites, notwithstanding their relative lack of wealth compared to Arzhan (Fig. 3) (Amartuvshin and Galdan 2013). Slab burials show systematic variation in size of construction and the numbers of ceramics, animal bones, bronzes, and long distance prestige items included in each assemblage, implying status differentiation among the select few buried in this manner.

Very likely, the groups who built impressive cemeteries like Tsagaan Uul were also those participating in down-the-line exchange networks reaching into Inner Mongolia, and were partly responsible for the dramatic similarities in material culture between Mongolia, South Siberia, and Inner Mongolia during the Early Iron Age. The prevalence of steppe style artifacts from the north (e.g. knives, daggers, arrowheads, buttons, and belt plaques) at sites of the Upper Xiajiadian culture (1200/1100—600 BC) in southeastern Inner Mongolia and the Ordos Bronze culture (c. 750–250 BC) of south-central Inner Mongolia attests to such contacts (Shelach 2009a). Likewise, the growing numbers of bronze artifacts originating in Inner Mongolia but recovered from northern and western Mongolian sites, such as a number of bronze helmets known from slab burials and surface contexts, help to confirm the extent of these early interaction spheres (Hudiakov and Erdene-Ochir 2010).

These prestige goods and identity networks of down-the-line interactions over much of eastern Eurasia help to explain the shifting mortuary formats of the Early Iron Age. A clear change takes place from landscape-scale collective construction projects during the Late Bronze Age to a new emphasis on interring wealth and long distance products within more elaborate and exclusive burials. In the western part of Mongolia and adjacent parts of Siberia this trend is manifested in the gradual replacement of khirigsuur and khirigsuur-like monuments (e.g. Mongun-Taiga) by stone, earth, and timber kurgan interments (e.g. Aldy-Bel/Uyuk-Sagly, Maiemir/Pazyryk, Chandman-Ulangom). In the east, large stone quadrangular and ‘cist-like’ burials emerged as a major monumental phenomenon (e.g. Tevsh-Ulaan Zuukh Cultures) and in a similar way these were replaced by slab burials (Honeychurch and Amartuvshin 2011; Navaan et al. 2009, p. 13). In the central regions of Mongolia these western and eastern material patterns intersect and many of these monument and burial types are found together in complex diachronic landscapes (Honeychurch et al. 2009; Horton et al. 2012). In general, these changes seem to suggest a widespread transition from community-oriented and participatory displays to a set of practices more suited to a restricted set of local factions who were well connected externally and favored a political ideology of leadership based on network relations.

Regional survey perspectives from areas across the Mongolian plateau also contribute significant information about these organizational shifts. Pedestrian survey projects in and around Late Bronze and Early Iron Age monumental centers show a pattern of multiple and dispersed complexes of monumental activities during the mid to late second millennium BC. During the early to mid first millennium BC, monumental burial construction became more spatially consolidated at a restricted number of sites (Honeychurch et al. 2009, pp. 340–341). These selected sites of more intensive investment were spatially consolidated in ways that created greater distance between major zones of monument building, suggesting the development of distinct centers with associated territories and perhaps even buffer areas between them (Gardner and Burentogtokh, submitted).

In addition to monument and cemetery distributions, surveys have also succeeded in discovering seasonal campsites inhabited during the second and first millennia BC (Honeychurch et al. 2007b; Houle 2010). Although research into such habitation sites has only been on a modest scale in Mongolia, there are many indications that lifeways of the Late Bronze Age were different from those of the Early Iron Age (Houle 2010; Machicek 2011). Variations in herding methods in different regions, higher mobility, and a broader range of mixed food sources argue for a more flexible and readily adaptable approach to daily existence (Murphy et al. 2013; Machicek and Zubova 2012; Machicek 2011; Honeychurch and Amartuvshin 2007). Although environmental and technological changes certainly transpired during the intervening centuries following the Late Bronze Age (Wagner et al. 2011), a major factor in the way pastoral nomadism developed was a dynamic political history that began to embroil nomadic households and communities in issues of territory, alliance, loyalty, and political ideology. These conditions transformed pastoral nomadism, not just as an economy, but also as a set of strategies for negotiating a novel socio-political existence on the steppe.

In conjunction with these defining transformations of the Early Iron Age, evidence for violence and warfare also demonstrates important geographic variability. Violent conflict was endemic in some regions, especially in the west and northwest of Mongolia and in South Siberia (Murphy et al. 2002; Jordana et al. 2009), but in others, such as north-central Mongolia and the middle and south Gobi, there exists no clear evidence as yet for warfare or interpersonal violence, despite substantial work on paleopathology, analysis of ‘weapon’ sets, and study of potential defensive locations (Machicek 2011; Nelson 2010; Honeychurch et al. 2009). This degree of variability is clear from other parts of the eastern steppe as well. For example, a recent comprehensive analysis of an Early Iron Age pastoral nomadic population in southern Xinjiang found little evidence for conflict-related trauma (Wagner et al. 2011, pp. 15736–15737). However, roughly contemporary nomadic groups directly to the north in Xinjiang and further north in the Altai region of Mongolia show pervasive signs of violent mortality among adult males (Eng and Quanchao 2013; Jordana et al. 2009; Naran 2004, 2007; Novgorodova 1982).

Burials of the first millennium BC furnished with decorated weapons and sometimes bronze helmets and armor have been commonly understood as belonging to a male warrior elite involved in frequent combat between neighboring pastoral groups. The bronze weapon and tool assemblages of some Early Iron Age burials are indeed impressive, but the material record often problematizes what seem to be straightforward expectations about the nature of conflict and violence. One such case is the cemetery of Jinggouzi (c. 650–350 BC) in southeastern Inner Mongolia, where careful skeletal analysis reveals that females, rather than young adult males, bore most of the evidence for conflict-related violent trauma (Eng and Quanchao 2013, pp. 238–239). Such discrepancies defy simple explanations for warfare and conflict among nomadic groups and encourage alternative thinking about burial evidence. Another analysis from Inner Mongolia argues that artifacts commonly viewed as weaponry were probably related to belief systems and transregional identities rather than to warfare (Shelach 2009b, pp. 262–264; cf. Johannesson and Machicek 2010). Clearly the role of conflict during the Early Iron Age is more complex than often assumed; however, in those parts of Mongolia where signs of violence are so far absent there is still comprehensive evidence for burial pillaging and/or desecration during the first millennium BC. This suggests that these areas likewise experienced some degree of competition and conflict as inequality, affiliation, and leadership increasingly became part of everyday life (Frohlich et al. 2009; Houle 2010, p. 189; Fitzhugh and Bayarsaikhan 2011, p. 188; Nelson et al. 2011).

Far-reaching exchange and alliance networks, wealth concentration, monument and burial elaboration, buffer zones between territorial centers, and signs of competition—all of these factors point to a process of consolidation around a number of central places which then integrated outlying communities into several discrete areas of concentrated political activity during the Early Iron Age. From this setting of what were still relatively small-scale polities, the Xiongnu state emerged, probably in the north-central river basins of Mongolia and Siberian Transbaikal (Honeychurch and Amartuvshin 2011). This brief overview of later eastern steppe prehistory establishes one central but often overlooked fact: the Xiongnu polity did not arise among dispersed egalitarian herders, but among groups which had had 800 or more years of experimentation with hereditary inequality, locally centralized leadership, and sophisticated political technique. In other words, the indigenous nomadic political tradition on the eastern steppe began long before the Xiongnu period and drew on cultural and political knowledge derived from centuries of experience with small-scale politics. This observation is consistent with recent archaeological models from many parts of eastern Eurasia, all of which emphasize similar long-term variables for understanding initial political complexity among steppe nomads. These include growing articulations between local and regional scales of interaction, and political processes focused on enduring inequality and exclusive leadership (Chang 2012; Shelach 2009a; Houle 2009; Honeychurch et al. 2009).

An Overview of the Xiongnu Archaeological Record

Developing the Xiongnu period material record is critical to understanding the nomadic politics of the Eurasian past. A great range of information is simply not found in textual sources, and many problems cannot be addressed using ancient documentary evidence. Questions persist not only about the emergence of the initial Xiongnu polity but also about the exact nature of the socio-political context in which this organizational transformation occurred, a context about which the early Chinese historians had little knowledge. With a primary focus on the archaeology of Mongolia, the following overview is intended to give a description of the major site types of Xiongnu archaeology and material patterns related to social organization. My emphasis is on the evidence archaeologists offer for socio-political differentiation, integration, and centralization, that is, for standard expressions of political complexity. I introduce two Mongolian study areas with high resolution survey and excavation data pertinent to these issues, which will appear throughout the discussion. These are the Egiin Gol valley in the forest-steppe zone of northern Mongolia, and the Baga Gazaryn Chuluu region in the northern Gobi Desert (Fig. 1).

Archaeological research on the Xiongnu period has been conducted for more than a hundred years across the steppe zone of Northeast Asia and has contributed substantially to anthropological debates about nomadic culture and society. The association of a specific archaeological culture with the historical Xiongnu polity was first proposed at the end of the nineteenth century, based on the burial excavations of Tal’ko-Gryntsevich in the Transbaikal region of Siberia between 1896 and 1903 (Tal’ko-Gryntsevich 1999). This hypothesis was further tested in the 1920s by the Kozlov expedition’s numerous excavations of well-preserved elite tombs at the Noyon Uul cemetery in Central Mongolia. The results of these field projects in Mongolia and southern Siberia revealed similarities in material culture and burial configurations. These early observations were also supported by Sosnovskii’s excavations in the 1930s and 40s at the Siberian cemeteries of Il’movaya Pad’ and Dyrestui (Fig. 1). By the mid twentieth century, Russian and Mongolian archaeologists had established that many of the excavated artifacts reliably dated to the period of the historical Xiongnu. This included objects of Han Dynasty manufacture, as would be expected. These results strengthened the original proposal that a specific material culture, mostly known from mortuary contexts, was likely related to the Xiongnu nomads of the Chinese histories (Konovalov 1975, pp. 17–18; Rudenko 1962, pp. 6–8; Ivanov 2011).

Surface survey and excavations at walled settlement sites by Davydova and Minyaev (2003) in Siberia and by Perlee (1961, pp. 17–39) in Mongolia, recovered artifact assemblages similar to those known from Xiongnu period cemeteries and began to add a much needed settlement perspective to the archaeology of this period. These excavations confirmed reports in the Han dynasty records of sedentary, agricultural centers in use among the Xiongnu. This material culture has now been documented across a large geographical area that includes all of Mongolia, sections of South Siberia, and some parts of Inner Mongolia. Contemporary artifact types and some burial practices extend into Manchuria, Kazakhstan and Xinjiang as well, probably indicating exchange and elite interactions with neighboring groups, including a substantial investment in the westward Silk Roads economy (Barfield 2001b).

In contrast, some archaeologists and historians have proposed that the Ordos region of Inner Mongolia and Ningxia was the probable center of material culture associated with the textual Xiongnu (Di Cosmo 1999, p. 953). These researchers identify a number of mid to late first millennium BC cemeteries, including Maoqingguo, Xigoupan, Taohongbala, Hulusitai, and Aluchaideng (Fig. 1) (Tian 1976; Tian and Guo 1986; Wu’en 1990) arises from a text-based geography identifying the Ordos as the Xiongnu homeland. Consequently, fairly weak evidence such as artifact styles not associated with the early states of China or the presence of domestic herd animals was deemed sufficient to link these sites to the textual Xiongnu. Subsequent analysis and dating have shown that the Ordos and much of Inner Mongolia was home to diverse groups that maintained significant connections to both the steppe zone of Mongolia and the Central Plain cultures of early China in the south (Shelach 2009a, pp. 126–133; Miller 2011b, p. 562; Indrisano 2006). The material culture and organizational patterns are different from those associated with the Xiongnu in Mongolia and also vary from place to place within the Ordos zone. There is little evidence for the kind of regional complexity seen in Mongolia (Holotová-Szinek 2011) and the few cemeteries with material patterns related to those in Mongolia are later in date (c. late second/first century BC—second century AD, Pan 2011).

Despites its long history, Xiongnu period archaeology in Mongolia is still very much in a developmental phase, employing new methodologies and analyses that focus on site types and data not previously considered. Regional survey, subsurface remote sensing, luminescence dating, artifact sourcing by compositional analysis, and bone isotope analyses are among many techniques now yielding new information about Mongolian prehistory. These approaches complement the traditional fieldwork emphases on mortuary analysis and monumental site mapping. The use of radiocarbon dating was initiated in Mongolia in the 1990s, and although there have been major accomplishments in site and ceramic periodization, eastern steppe archaeology still struggles with the problem of relatively unrefined chronology. For the Xiongnu period, chronological data represent at best 100–200 year spans. The problems and questions of dating will be discussed throughout this review. Despite these limitations, archaeologists have developed evidence to test major models for steppe lifeways, showing that material patterns sometimes contradict the long-accepted statements of ancient historians and modern ethnographers.

Mortuary Differentiation

Of all Xiongnu period site types, burials and cemeteries are by far the best known and the most studied. There are two primary forms of elite burial during the Xiongnu period: one with an embanked ring feature made of stone and soil, and the other with a large platform-like mound and several levels of deeply interred construction (Figs. 4, 5) (Minyaev 1985). Both are labor-intensive, contain imported items and precious materials, and have prominent cemetery locations. Of the two, the smaller and more widespread form is the Xiongnu period ‘ring’ burials (Konovalov 1976; Tseveendorj 1985; Torbat 2004). These have substantial ring features on the surface, measuring up to 14 m in diameter, and below this ring of stones are pit interments ranging from 1.5 to 4 m in depth.

Bird’s eye and profile views of a typical Xiongnu period ring burial. The context is Grave 1 from the cemetery site of Khudgiin Tolgoi, as seen in the site plan. Below that is a detailed rendering of the wooden plank coffin found within the burial chamber (after Yun 2009)

Cut-away view of platform burial 20 from the elite cemetery of Noyon Uul (after Polos’mak et al. 2008)

Interred individuals were placed in a supine position and oriented to the north, northeast, northwest, or much less often, to the east or south. Burial chambers consist of an internal construction that might comprise a simple earthen pit, a pit with stone slab siding, a wooden coffin, or an elaborate coffin in a timber frame enclosure. Finds have included the remains of domestic herd animals and wild fauna, ceramic vessels and bone tools, iron, bronze, silver and gold artifacts, and long-distance goods from China, Central Asia and even the Mediterranean (Lankton et al. 2012). Burial sites vary in make-up from a single burial to groups of over 350 ring burials. Examples of such cemeteries in Mongolia with significant research results are: Burkhan Tolgoi (at Egiin Gol) (Torbat et al. 2003); Khudgiin Tolgoi (Yun 2009); Tamiryn Ulaan Khoshuu (Khatanbaatar 2007); Shumbuuziin Belchir (Miller et al. 2008); and Alag Tolgoi (at Baga Gazaryn Chuluu) (Amartuvshin and Khatanbaatar 2010, pp. 232–242). Two cemetery sites from Siberia that have been equally intensively studied and are critical to understanding variation in mortuary patterns are Ivolga and Dyrestui (Fig. 1) (Minyaev 1998; Davydova 1996).

Ring-shaped burials are also commonly associated with the second type of interment, sometimes described as ‘platform’ or ‘terrace’ tombs. Major cemeteries with these large and impressive burials include Tsaram, Noyon Uul, Gol Mod 1and 2, Duurlig Nars, and Takhiltyn Khotgor (Fig. 1) (Minyaev and Sakharovskaya 2007; Polos’mak et al. 2008; Yerool-Erdene 2010; Erdenebaatar et al. 2011; Yun and Chang 2011; Miller et al. 2009). The large raised platform-like constructions are oriented approximately north–south, and consist of a low rectangular or slightly trapezoidal earth and stone mound, ranging in dimension from 8 to 46 m on a side, with a height of up to 2 m above the modern surface. On the south side there is a sloping entryway as much as 37 m in length that accesses the upper levels of a central burial chamber that is usually much deeper than that found in ring burials. The burial pits of these tombs reach up to 18 m in depth and the construction work overlying the chamber consists of multiple layers constructed from soil, stone, and wood (see Brosseder 2009, p. 256 for summary data).

Though there is variation in components, the burial chamber itself includes an inner and outer wooden construction of hewn logs, usually of larch or pine. Within the inner chamber, a wooden coffin, often decorated with gold ornaments and holding an interred individual, is sometimes found, though disruption from pillaging or desecration has usually destroyed the internal contexts of these sites. A wide range of faunal remains is also commonly recovered, primarily horse bones, but also skeletal material of cattle, sheep and goats, and wild animals. Though furnishings can be quite variable, the richest of these tombs contain precious metals and stones, large ceramic vessels, felt and woven fabrics, silks, glass and jade items, bronze mirrors, lacquer ware, and gilded horse gear. The geographical origins of these artifacts include China, Central Asia, South Asia, and the Mediterranean. Among the most impressive burial furnishings are Han Dynasty horse-drawn carriages interred in their entirety within some burial pits (Yerool-Erdene and Gantulga 2007).

Archaeologists have made substantial advances in dating these contexts, especially using AMS radiocarbon analysis; however, it is still too early to confidently delimit the chronological range of either of these burial practices. I present new radiocarbon dates for ring burials below, and while absolute dates from platform tombs so far fall within the first century BC to first century AD, reliably dated contexts are very few (approximately seven contexts, with some additional dates forthcoming, cf. Brosseder 2009, pp. 268–269). Because of this under-specified chronology, researchers are unable to explain the geographical spread of these two different burial practices, though some promising hypotheses have been developed (Miller 2009; Honeychurch and Amartuvshin 2011; Eregzen 2011a). From a societal perspective, some archaeologists argue that these very large platform burials were likely related to the ruling houses of the Xiongnu polity (Minyaev and Sakharovskaya 2007, p. 201; Polos’mak et al. 2008, pp. 85–87). The smaller ring burials, on the other hand, may have been the burial treatments provided to different ranks of intermediate or local level elite (Honeychurch et al. 2007a).

In those few instances where demographic and genetic analyses have been done, evidence suggests that relatively few members of society were accorded either of these mortuary treatments. In the Egiin Gol valley of north-central Mongolia, all Xiongnu period cemeteries located by pedestrian survey represent a total of a little more than 100 individuals out of an estimated population in the thousands over the time period when these cemeteries were in use (Honeychurch et al. 2007a). Based on ancient DNA analysis from the Burkhan Tolgoi cemetery at Egiin Gol, a significant number of interred individuals were genetically related. In the earliest sectors of that site the genetic lineages represented were relatively few, which suggests that only one or two local groups were involved in the initial adoption and use of Xiongnu mortuary practices (Keyser-Tracqui et al. 2003, p. 258).

Although some archaeologists view the more numerous ring-shaped burials as those of commoners (Torbat 2004), the above demographic analysis argues against that idea. Instead, common people likely employed simpler methods of burial; however, archaeologists have had little success in documenting these. Simpler Xiongnu mortuary practices might have included cremations, unmarked burials, or surface exposure of bodies. Otherwise, commoners may have used shallow pit interments marked with just a few unobtrusive stones, as has been documented at the Gobi desert site of Baga Gazaryn Chuluu (Nelson et al. 2009). In contrast, the burial practices for the elite correspond with what Gina Barnes calls ‘material stratification’: distinctive material patterns involving rare items, large-scale and labor-intensive constructions, and significant locales available only to a restricted segment of the population (Barnes 1986, pp. 83, 88, 2007). While the basis for local and regional elite leadership still requires much study, the material and textual evidence for Xiongnu socio-political stratification is consistent and compelling (Kradin et al. 2004; Minyaev 1985).

Settlement and Economic Diversity

Habitation and activity sites of the Xiongnu period also show substantial differences in size, construction, and composition, in spite of the fact that, to date, very few of these settlements have been systematically studied (Bemmann 2011). Archaeologists have located seasonal campsites of herding families, as well as large seasonal settlements that may have been associated with local elite activities (Honeychurch and Amartuvshin 2007; Houle and Broderick 2011). In addition to these campsites, large settlements having more intensive use and significant infrastructural investment have also been investigated. One example from the Egiin Gol valley (EGS 131) is a site with an extensive wall and ditch system perched above the main river on a substantial rise. Test excavations discovered a sparse ceramics scatter and a bronze mirror imported from China, but there was little evidence for consistent or repeated occupation. The function of this site is still unknown; but, given its prominent and defensible location, it may have been for temporary protection or possibly for hosting ceremonial events (Honeychurch 2004, pp. 133–135).

Much larger walled and open settlement sites have been mapped and excavated in Siberia and Mongolia as well. Many of these have planned layouts and include semi-subterranean houses, workshop areas, large central architectural structures, and very different kinds of use histories. The prominent settlements of Boroogiin Suurin in Mongolia or Ivolga in South Siberia are clearly village-like occupations where multi-resource production, including farming, herding, and craft specializations, were practiced (Fig. 1) (Davydova 1995; Pousaz et al. 2007). Others, such as the walled sites of Tereljiin Dorvoljin and Bayan Under may have been elite residences or ritual centers (Figs. 1, 6) (Danilov 2011). This range of site structures, arrangements, and sizes suggests a great deal more functional and economic differentiation than is generally expected for steppe societies.

Plan of the walled settlement site of Bayan Under in southern Buryatia, Siberia. Black fill shows areas of excavation (after Danilov 2011)

Additional evidence for differentiation comes from a number of recent studies on Xiongnu craft production in iron and ceramics. The material culture of the Xiongnu period is distinguished from that of preceding periods by the preponderance of iron metallurgy and novel forming and firing techniques for ceramics. As I will argue below, the earliest indication of local change associated with the Xiongnu phenomenon is the appearance of iron objects and Xiongnu style ceramics in pre-Xiongnu period burial and monument contexts. Archaeologists now know that craft production was carried out at both specialized workshops and seasonal campsites. These patterns were documented by the recently excavated ceramics kiln and iron production areas at Khustyn Bulag (Fig. 1) (Amartuvshin et al. 2011, 2012) and by the discovery of small-scale iron working at campsites in the Khanui valley (Fig. 1) (Houle and Broderick 2011).

Due to a presumed contradiction between mobility and craft production (e.g. Menon 2003), researchers often attribute such industries as metal working not to steppe peoples but to displaced laborers from China (e.g. Kradin 2005p. 80). In fact, the iron working process employed at these sites was quite different from the contemporary methods practiced in China and was most likely an indigenous technology or one brought in from western regions (Park et al. 2010). Craft production was also not just a small-scale, local, or household endeavor. Ceramics manufacture at the Khustyn Bulag kiln seems to have included not only a range of vessel forms but also building materials used at a walled settlements 50–80 km away (Eregzen 2011b, pp. 94–95). This evidence contradicts historical research arguing that steppe peoples had a one-sided and relatively unstable pastoral economy that would not have supported the infrastructure needed for sophisticated craft work (Khazanov 2003, pp. 28–29). Such arguments lead to the suggestion that, as a result, nomads would have been dependent or semi-dependent on neighboring sedentary states for these goods, either through frontier trading or raiding (Khazanov 2001; Jagchid and Symons 1989). The archaeological evidence from the Xiongnu period clearly does not support this argument.

Political Integration and Centralization

Given these patterns of social and productive differentiation, the next question is what forms of integration bound together segments of Xiongnu society, and to what degree was central authority involved? While archaeologists have not yet focused directly on the problem of integration and centralization, historians have long debated the make-up of the Xiongnu political fabric and especially the role of the royal court. The Shiji historical account of Xiongnu organization discussed above seems to describe a centralized organization based on regional hierarchy, local area integration, and some version of administration. However, historians interpret these passages in very different ways, with some emphasizing central rule and others arguing for the local autonomy of internal groups (e.g. Mori 1950; Yamada 1982). As with most archaic states, there is good reason to believe that central authority was neither stable nor absolute, but instead varied between modes of greater and lesser centralization over time (Sneath 2007).

In archaeological terms, this question is best addressed by looking at patterns of structured interaction between geographically separate communities. Specifically, interactions that create political inter-dependence provide evidence that local groups and leaders were not as autonomous as some historical models might suggest (e.g. Barfield 2001a, p. 13; Di Cosmo 2002, pp. 224–227; Kürsat-Ahlers 1996). In most cases, those Xiongnu period contexts displaying such patterns were associated with practices that helped to maintain relationships between elites. Studies of local and non-local materials at the Egiin Gol and Baga Gazaryn Chuluu sites give some indication of the importance of these intra-steppe interactions. As an example, chemical compositional analyses of ceramics and clays from the Egiin Gol valley and major sites in Siberia demonstrate long distance transport of pottery (Fig. 7) (Hall and Minaiev 2002; Honeychurch 2004, pp. 172–203). These studies also show that Egiin Gol habitations of substantial size (e.g. approximately four hectares), and often with distinctive artifacts including coins from China, armor plate, horse gear, and so on, had disproportionately more of these non-local ceramics than other local sites. This suggests pottery transport, use, and deposition by way of visitation, gifting, feasting, or other activities carried out at and around what were probably local elite encampments. Elsewhere I have argued that this evidence, along with the unique locations of these sites along major pathways of travel, might be associated with the itinerant circulation of nomadic leadership as one approach to sustaining regional integration (Honeychurch and Amartuvshin 2007; Honeychurch et al. 2007b).

Mortuary evidence from Baga Gazaryn Chuluu in the Gobi desert makes a good case for inter-area dependencies, probably also linked to itinerant elite movements. Xiongnu period burial practices at Baga Gazaryn Chuluu conformed closely with those known from northern Mongolia and Siberia, including lavish use of forest woods and other forest products. Substantial amounts of expertly worked pine and birch wood have been recovered from burial assemblages in the form of coffins, coffin covers, and containers (Amartuvshin and Khatanbaatar 2010). One burial of an adult male individual even contained a degraded but complete set of elk antlers (C. canadensis sibiricus) (Amartuvshin and Khatanbaatar 2010, p. 233). These plant and animal species belong to forested environments and were not present at Baga Gazaryn Chuluu in the past. Their appearance in the desert indicates that local Gobi individuals of some prominence maintained relationships with groups to the north that provided symbolically important materials from the forest zone, several hundred kilometers away.

In fact, the extent to which Baga Gazaryn Chuluu burials generally conform to Xiongnu period mortuary practices is in itself quite striking and suggests that adherence to a common sumptuary code was important. There is indeed local variation in burial practices that needs to be better understood (Miller 2011b; Yang 2011; Brosseder 2009), but what is particularly interesting and pertinent to the question of central authority is that burials in outlying western and southern areas, with ready access to Central Asian and Chinese prestige goods, still seem to adhere closely to sumptuary codes. The significance of this observation is underscored by a statement from steppe historian Joseph Fletcher, who argued that, ‘[Xiongnu] tribes forfeited very little of their autonomy [to central leadership] … just enough to seem united for the sake of extorting wealth from the Chinese … and in warfare each person kept what plunder he seized’ (Fletcher 1995, p. 21).

If such local area autonomy indeed had been the rule, then in areas closer to the Han Dynasty frontier there would presumably have been a surplus of Chinese prestige goods, greater incidence of these in burials, and a breakdown of sumptuary patterns. The very opposite seems to be the case at Baga Gazaryn Chuluu (BGC), where, as indicated above, burials are very much like those in the north and by and large obey a similar set of rules. This may be taken as indirect evidence that the behavior of local leadership was regionally governed to a greater degree than historians have imagined. A centrally managed re-distribution of Han Dynasty status objects to local areas closer to the frontier would probably have involved slightly greater numbers of such goods to offset independent methods of acquisition. The southernmost Xiongnu cemeteries in Mongolia seem to fit this pattern of controlled distribution better than Fletcher’s proposed frontier model (Honeychurch 2014).

Finally, moving to the broadest scale of analysis, some researchers have recently suggested that a roughly tripartite site hierarchy is apparent at the macro-regional scale of Xiongnu material culture distribution. Province by province cultural heritage projects sponsored by the Mongolian government have supported extensive low-resolution jeep surveys throughout many of the regions beyond the center of Mongolia. The first country-wide synthetic database for Xiongnu sites was assembled in the years 2000 and 2001 and has been significantly enlarged over the past decade, since new settlements and cemeteries are discovered on an almost yearly basis. From these provincial distribution maps, Mongolian archaeologists now argue for a clear difference in the size, density, and diversity of sites within the central part of Mongolia as compared to those in the western and eastern flanks of the distribution (Yerool-Erdene 2010, pp. 26–28).

Interestingly, the central, eastern, and western sectors are all marked by elite platform burial cemeteries, but there are greater numbers of these sites and much larger cemeteries in the central region, which itself has a western and eastern sub-division (Fig. 8). Mongolian archaeologists have compared this roughly tripartite pattern to the textual description of a central, eastern, and western geographical division marking the underlying regional hierarchy of the state (Yerool-Erdene 2011). As a textual–material hypothesis, this idea requires substantial testing through systematic archaeological fieldwork in the eastern and western parts of Mongolia. If correct, however, the geographical layout of the polity would not only suggest a dominant central region, but also the capacity to reliably delegate authority far beyond the center, a feature reminiscent of a more specialized administrative body (Honeychurch and Amartuvshin 2011; Wright 1977, p. 383). The possibility of a unique version of nomadic administrative organization has in fact been supported by some interpretations of the early Chinese historical texts (Bondarenko et al. 2003, p. 12; but cf. Kradin 2011, pp. 95–96).

Regional map of all known cemeteries with elite platform style burials. These cemeteries have both ring and platform burials and the counts provided are the total number of surface features assessed for each cemetery (see Yerool-Erdene 2010, p. 18)

In summary, I have attempted to provide a descriptive and informative overview of Xiongnu archaeology as known from Mongolia, with an emphasis on general organizational patterning. While the above patterns are highly suggestive, they are also still preliminary and require further evaluation in different parts of the eastern steppe zone. An additional problem with such an overview is that it uses a synchronic time frame which, in fact, compresses more than 300 years of human activity. This points to the lack of finer chronology that would allow for a more detailed disaggregation of these organizational patterns in time and space. Despite these obvious limitations, I believe these patterns do speak to the issue of regional complexity as a defining characteristic of the Xiongnu period. This preliminary assessment of the material record is not inconsistent with the early historical accounts of a large-scale, centrally integrated Xiongnu state; that is, exactly the kind of organization we would expect as the primary competitor of the Han empire. Still unanswered, however, is the question of when and how this nomadic version of regional complexity first began to emerge in Mongolia.

The First Steps Towards Regional Complexity

Few areas in Mongolia have been studied comprehensively enough to allow us to answer this question in any detail (Wright et al. 2009; Honeychurch et al. 2007b). Surveys combined with habitation and mortuary excavation at Egiin Gol and Baga Gazaryn Chuluu provide new information for local processes immediately prior to the Xiongnu polity. During the early-to-late mid first millennium BC, the two regions were characterized by a similar set of material patterns described above as slab burial culture (Erdenebaatar 2002). Slab burial sites date up to the final phase of the Early Iron Age, just prior to Xiongnu state formation. Habitation sites associated with the period of slab burial construction tend to be small, averaging 2,500 m2, and marked by sparse ceramic scatters of coarse, low-fired, red and brown ware pottery. The Xiongnu period brings radical transformation to both of these research areas. What these transformations meant, and under what local and regional conditions they transpired, are questions I address below in some detail. I begin with an overview of the chronologies involved and follow with a discussion of survey site patterns and mortuary and landscape evidence from fieldwork at Egiin Gol and Baga Gazaryn Chuluu.

Issues of Chronology

As calculated from the historical sources, 209 BC is the year that Maodun founded the Xiongnu state after having been forcibly expelled from the Ordos region of Inner Mongolia by armies of the Qin empire (Watson 1993, pp. 134–136). Based on this narrative, the very end of the third century BC has become almost an article of faith in the dating of Xiongnu material remains. Those archaeologists working in the historical tradition firmly expect patterns of complex organization to arise after 209 BC, though the historical texts do mention some form of regional-scale organization prior to this date (Linduff 2008, p. 177). When dating evidence is absent, researchers usually relegate Xiongnu style burials and material culture to the second century BC—first century AD by default. Given the growing radiocarbon database for these sites, and preponderance of dates in that range, this does not seem a bad assessment. However, based on historical sources and stylistic dating, some researchers dispute chronometric dates for contexts in Mongolia and Siberia falling before the late second or the first century BC (Minyaev and Elikhina 2009, p. 28). To complicate matters, another group of researchers question radiocarbon dates with probability ranges in the third and second centuries BC because of a diet-based reservoir effect on human bone collagen from consuming fish (Brosseder and Yerool-Erdene 2011).

These arguments need to be contextualized somewhat in terms of the field practices, curation, and artifact storage implemented by international research teams. The use of radiocarbon analysis in Mongolian archaeology is still relatively new. Collaborative projects working in Mongolia are developing best practices for the reporting of dates, sample collection, and curation of samples and context information to ensure reliable dating and re-dating. The analysis of multiple radiocarbon dates within a region in some instances has been hampered by a lack of full reporting of laboratory results in earlier reports and publications (e.g. Table 1). In addition, there have been problems with the reliability of context information for curated samples collected in the past. This has led to a situation in which chronometric date ranges are sometimes difficult to assess or even to cite reliably as evidence, which has understandably fostered skepticism among a research community predisposed towards textual sources of evidence. As a result, historians and historically trained archaeologists are sometimes reluctant to accept a laboratory produced date when it contradicts authoritative statements in the historical accounts.

Nevertheless, radiocarbon dating has led to major improvements and revisions in site periodization over the past two decades. In the case of Xiongnu archaeology, there is a growing number of recent and reliable radiocarbon analyses of well-contextualized samples with sigma 1 and/or 2 probability ranges overlapping the fourth, third, and second centuries BC (Table 1). These dates come from regions that have both riverine and arid environments in Mongolia, from different site types, and from different kinds of sample materials. While a reservoir effect from consuming fish is a potential problem in the northern river zone, without additional isotopic testing of human and fish bone, and without full publication of prior radiocarbon dates for comparison to the re-dating tests, this argument is still very much in the making. For the time being, these early radiocarbon results should be considered not as outliers or problematic analyses, but as indications that a particular set of material culture and associated social changes likely appeared in Mongolia earlier than previously thought.

Patterns of Transition in the Egiin Gol Valley

The Egiin Gol survey area is located in the northern forest-steppe region (Fig. 1), where both pastoral and agricultural resources are abundant. The valley contains the Eg River and is surrounded by prominent ridges and tributary streams draining several substantial side valleys. The earliest sign of Xiongnu-associated material culture at Egiin Gol is the appearance in a very few early contexts of ceramics sharing forms and decorations with Xiongnu pottery. These ceramics have been recovered from two pre-Xiongnu slab burial assemblages (Torbat et al. 2003, pp. 33, 36) and from a Late Bronze Age khirigsuur monument complex (Hall et al. 1999, pp. 136–137). In the latter case, the ceramics were discovered atop a rectangular stone feature within a khirigsuur complex and probably placed there long after the monument’s construction. Sherds from two different pots were recovered along with two types of bronze arrowheads typically found in slab burial contexts. The sherds and arrowheads were found together and the pottery in question (Darkhan Uul Type 6) was most likely manufactured locally (Hall et al. 1999, p. 146). The sherds, however, differ from slab burial pottery in the use of thong-wrapped paddle-and-anvil construction and slow-wheel finishing. Moreover, the original ceramic vessel was a large jar with small mouth, narrow neck, and an everted rim. These features are strongly suggestive of Xiongnu style ceramics (e.g. Fig. 7), even though other decorative elements and the firing technique are non-typical. Given that this early monumental context has long been a place of activity and deposition (even up to the present), the association of these ceramics with the pre-Xiongnu arrowheads and stone feature is suggestive though not certain.

The two excavated slab burials with Xiongnu-style ceramics give rise to some more definite observations. Since both burials had been disrupted in antiquity, the possibility remains that the Xiongnu-style ceramics were intrusive (Torbat et al. 2003, p. 43); however, these slab burials have additional characteristics indicating a late periodization. In addition to these novel ceramics, both slab burials have a northern or northeastern orientation, usually indicative of Xiongnu period burial practices. Moreover, one of these slab burials (EGS 118) contained iron artifacts and provided a radiocarbon sample that dated to 396–341/327–204 BC (95 % probability, Table 1). These characteristics have prompted speculation as to whether the EGS 118 context might in fact be something other than a slab burial (Wright 2011). However, the slab-based construction and size, the recovery of other more typical slab burial artifacts, and the location near a second slab burial all support the Mongolian excavators’ original interpretation of this context as indeed a later period slab burial (Torbat et al. 2003, pp. 36, 45).

This initial evidence for new ceramic types and iron artifacts during the fourth/third century BC at Egiin Gol is contemporary with, or very close in time to, the establishment of an important habitation site (EGS 110) that also has Xiongnu-style ceramics. At the lowest levels of this site, excavations revealed a hearth dug into sterile soils, with the same Xiongnu style ceramics scattered both around and in the hearth feature, along with carbonized bread wheat (T. aestivum). A sample of bread wheat from the feature has been radiocarbon dated to 388–197 BC (95 % probability, Table 1). Given the stratigraphic context, this date range represents an initial occupation of a new site in a previously unoccupied part of the valley. A single date of course cannot indicate the full period of occupation at the site, but given the relatively dense artifact scatter there, occupation and re-occupation may have continued for some time. This settlement area was probably also used seasonally during warm months since the main river valley is exposed and subject to extreme winter conditions. Furthermore, the initial area of this settlement is not known but, in time it grew to 11,000 m2, becoming one of a number of sites in the valley that established a new kind of habitation pattern specific to the Xiongnu period.