Abstract

While entrepreneurial ecosystem research has attracted increasing attention in the scholarly literature, research focusing on its structure beyond geographical borders is limited. The aim of this paper is to examine the configuration of the entrepreneurial ecosystem and propose an original model by implementing an international perspective. Specifically, this study combines the following two theoretical streams: the entrepreneurial ecosystem and the international context. An empirical investigation was performed through an exploratory study of key public and private French internationalization support organizations. The findings provide new insights related to 4 axes, i.e., structural, systemic, evolutionary and spatial axes, which are enhanced by the adopted international perspective. This perspective is connected to a glo-cal culture that combines both adaptation to local specificities and global integration. The findings also underline the importance of sub-ecosystem interactions in establishing a consistent and effective long-term entrepreneurial development strategy in a territory. This research provides useful implications for both theory and practice, especially for policymakers and support organizations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

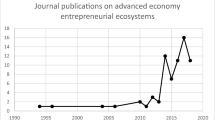

The entrepreneurial ecosystem (EE) has become a popular focus of analysis in the scholarly community, which has fostered an expansion phase and triggered an increasing number of associated publications during the last three yearsFootnote 1 (Alvedalen and Boschma 2017; Autio et al. 2018; Malecki 2018; Tsujimoto et al. 2018; Cavallo et al. 2019). However, the literature on entrepreneurial ecosystems has mainly adopted cartographic, structural and systemic perspectives (Isenberg 2011; Stam 2015; Spigel 2017; Roundy et al. 2018; Stam and van de Ven 2019). These perspectives use different categories of attributes to depict the entrepreneurial ecosystem (Spigel 2017). This ecosystem is also characterized by the interactivity of these attributes and the strategic multilateral dynamics among various actors according to their individual roles and bargaining powers (central or peripheral) (Adner 2017; Theodoraki et al. 2018). To understand the mechanisms of the entrepreneurial ecosystem, previous research emphasized local cultural specificities (Audretsch and Belitski 2017), the ecosystem’s evolution (Mack and Mayer 2016), the entrepreneurial process (Spigel and Harrison 2018), the ecosystem’s governance (Colombelli et al. 2019; Colombo et al. 2019), and the multilevel approach (Theodoraki and Messeghem 2017).

The entrepreneurship literature generally defines the entrepreneurial ecosystem as “a dynamic, institutionally embedded interaction between entrepreneurial attitudes, ability, and aspirations, by individuals, which drives the allocation of resources through the creation and operation of new ventures” (Ács et al. 2014, p. 479). This dynamic interaction determines multiple other interactions between individuals and organizations that shape the ecosystem. However, despite the growing interest in this stream of research, it remains undertheorized (Acs et al. 2017; Spigel and Harrison 2018). The distinction between entrepreneurial ecosystems and other concepts seeking to explain the geographic anchoring of entrepreneurial activities (e.g., clusters, regional innovation systems, and networks) is still unclear. Likewise, the regional development research establishes the territorial boundaries of the entrepreneurial ecosystem to clarify its definition and facilitate its acceptance by academics (Audretsch and Belitski 2017).

Scholars partially adopt an international perspective of this ecosystem by focusing on the role of born globals (Velt et al. 2018), large multinationals (Ryan et al. 2020) and cross-border platforms (Nambisan et al. 2019); however, scholars fail to provide a holistic foundation for this perspective. Moreover, Guerrero et al. (2020) analyzed the link between ecosystems and the entrepreneurship process across developed and developing economies. Their systematic literature review shows how the context influences the type of entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial stage. However, these authors addressed the question of local entrepreneurial ecosystems in different types of countries without analyzing the international aspect of the entrepreneurial ecosystem. Therefore, the literature lacks a holistic international lens that can widen our understanding of this phenomenon and pave a new way of thinking regarding the role of entrepreneurial ecosystems in the international context (van Weele et al. 2018). Therefore, the current research explores the entrepreneurial ecosystem and the effects of digitalization and internet attention without incorporating other insights from a different stream of literature suggesting that international entrepreneurship extends across markets and boundaries; in turn, this approach suggests a mandate for a new research perspective (Nambisan et al. 2019). Beyond the promising insights garnered from the international perspective, prior studies concerning entrepreneurial ecosystems are generally restricted to focusing on a domestic context despite the significant evidence provided by the international entrepreneurship literature that the international context may be more compelling and relevant. Based on the above research gap, this paper provides an initial analysis of the entrepreneurial ecosystem in the dynamic international context using a multi-level approach (Velt et al. 2018).

In fact, scholars recognize that the entrepreneurial ecosystem is a multi-layered concept composed of several sub-ecosystems that co-exist, co-evolve and are embedded in different levels of analysis (O’Kane et al. 2020). Theodoraki and Messeghem (2017) utilize the macro-level to describe the entrepreneurial ecosystem, the meso-level to describe the entrepreneurial support ecosystem and the micro-level to describe the business incubator ecosystem. Support entities, especially incubators, are useful tools for creating global communities in local settings (van Weele et al. 2018). In this study, we define an internationalization support ecosystem (ISE) as a complex sub-ecosystem embedded into the entrepreneurial support ecosystem that encompasses the complex relationships among the specific actors, factors and processes involved in the internationalization support of entrepreneurs, even those beyond territorial borders. Previous research has shown increasing interest in internationalization support services to strengthen firms’ resources, improve their international performance or facilitate their entry into foreign markets (Bannò et al. 2014; Catanzaro et al. 2019; Malca et al. 2019). Moreover, internationalization is increasingly considered crucial for firms’ survival, growth, and long-term viability (Bannò et al. 2014). The cross-border expansion of businesses can be considered an entrepreneurial act (Jones et al. 2011; McGaughey et al. 2016; Schwens et al. 2018). However, the entrepreneurial act of internationalization is fraught with risks and uncertainty (Catanzaro et al. 2019). Consequently, many governments have developed policies that support the internationalization of firms (Lederman et al. 2010) and the emergence of entrepreneurial ecosystems dedicated to internationalization support, which involve specific players and support services. Similarly, knowledge regarding which ecosystem characteristics have the greatest impact on the international success of companies is limited (Love and Roper 2015). In fact, we have little information on the elements of this ecosystem that facilitate the international entrepreneurial activities of companies and thus contribute to a dynamic business environment and the economic development of a territory.

To fill these gaps in the literature on entrepreneurial ecosystems and internationalization support, we propose that the following question is studied: how does an international perspective refine the conceptualization of the entrepreneurial ecosystem? Empirically, we draw on an exploratory qualitative methodology and conduct 20 semi-structured interviews with the main actors involved in the examined ISE. This analysis establishes a new model of the entrepreneurial ecosystem while respecting its territorial and international foundations. Our results highlight the crucial role of the ecosystem’s glo-cal nature and sub-ecosystem interactions as an engine of economic growth. We hope that this exploratory study will establish a new way of exploring this phenomenon and serve as a basis for incorporating internationalization into the concept of the entrepreneurial ecosystem.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the theoretical background of this study by examining the literature on the entrepreneurial ecosystem and internationalization support to anchor our international perspective. Section 3 presents the exploratory methodology used to analyze the French internationalization support ecosystem, and Sect. 4 presents our empirical results. Finally, Sect. 5 concludes by discussing the most salient results and contributions of this study and avenues for future research.

2 Internationalizing the entrepreneurial ecosystem

2.1 The entrepreneurial ecosystem

The existing literature on the entrepreneurial ecosystem has been expanded in an anarchic way. Several directions to study and understand the entrepreneurial ecosystem have been proposed. However, we identify four major axes that structure the literature on entrepreneurial ecosystems: the structural axis (Isenberg 2010, 2011, 2016; Spigel 2017), the systemic axis (Stam 2015; Roundy et al. 2018; Theodoraki et al. 2018), the evolutionary axis (Mack and Mayer 2016) and the spatial axis (Acs et al. 2017; Audretsch and Belitski 2017) (see Table 1).

More precisely, the early studies were devoted to understanding the actors and factors constituting the ecosystem. Isenberg’s (2010, 2011, 2016) pioneering work made it possible to establish the structural axis by presenting the first model of the entrepreneurial ecosystem; this model encompasses six domains (policy, finance, culture, support, human capital and markets) that contain twelve elements (e.g., success stories, business angels, infrastructure, education, etc.). This first model is considered normative and descriptive because it lists the elements of successful ecosystems. Thus, Spigel (2017) contributes to the improvement of this model by categorizing the attributes of the entrepreneurial ecosystem, namely, the material (e.g., infrastructure), cultural (e.g., histories of entrepreneurship) and social (e.g., networks) attributes. These studies favor a configuration-based approach and make it possible to structure the entrepreneurial ecosystem. Other studies provide a distinction between the external factors that describe the ecosystem’s environment and the internal factors related to its members (Xie et al. 2019).

In the systemic axis, scientific research is further developing the configuration approach by evaluating the strategic interactions between the abovementioned elements, the interactivity of the ecosystem’s dimensions, and the dynamism of social capital as well as its crucial role in ensuring the proper functioning of the ecosystem (Neumeyer and Santos 2018; Theodoraki et al. 2018; Thompson et al. 2018; Neumeyer et al. 2019). This axis complements the structural axis by emphasizing the interactions and interdependence among the various dimensions, categories and attributes. In this axis, the theory of networks and social capital is used to explore the entrepreneurial ecosystem’s dynamics (Neumeyer et al. 2019). Theodoraki et al. (2018) propose a more dynamic version of the entrepreneurial ecosystem composed of three interconnected dimensions: the structural (ties, configuration and stability), cognitive (shared goals, language, and narratives) and relational (identification, members obligations, norms, and trust) dimensions. The literature corresponding to this axis focuses on the entrepreneurial ecosystem as an entity (Ács et al. 2014; Mason and Brown 2014; Morris et al. 2015; Roundy et al. 2018). Each actor is part of a system, and each individual action can lead to collective interactions.

The evolutionary axis focuses on the temporal maturity of the entrepreneurial ecosystem and its evolving processes (Mack and Mayer 2016; Spigel and Harrison 2018). Specifically, this axis explores how entrepreneurial ecosystems evolve over time and, according to certain authors, gain a certain durability (Mack and Mayer 2016) or sustainability (Cohen 2006; Theodoraki et al. 2018). Furthermore, we include recent studies that focus on the evolution of the ecosystem under the influence of the entrepreneurial process in this group (Spigel and Harrison 2018). The thesis defended in this stream of literature is that the adoption of an effective long-term entrepreneurial development strategy that defines the economic and social conditions is necessary for the establishment of a self-sustained entrepreneurial ecosystem. This reflective approach argues that the process of business creation and development provides a framework for studying the entrepreneurial ecosystem.

The spatial axis anchors the entrepreneurial ecosystem through its territorial dimension (Acs et al. 2017; Audretsch and Belitski 2017; Bruns et al. 2017). In this axis, the entrepreneurial ecosystem is considered an outcome of entrepreneurial territorial strategies. The contribution of this axis is the consideration of territorial specificities for the sustainability and durability of the entrepreneurial ecosystem. In addition, this axis contributes to a better understanding of the entrepreneurial ecosystem by distinguishing it from the clusters established by Porter (2000). The entrepreneurial ecosystem focuses on the entrepreneurial activity of companies within specific territorial contexts (Brown and Mason 2017). This concept is broader than that of clusters (Pitelis 2012). While the industrial cluster approach focuses on the “geographic concentrations of interconnected companies” and the national/regional innovation systems approach focuses on networks of knowledge-producing entities that increase a region’s innovativeness, the concept of the entrepreneurial ecosystem refers to the interconnected actors and factors that generate entrepreneurship as an output (Acs et al. 2017). Therefore, this axis includes the territorial nature of the entrepreneurial ecosystem as a crucial element of its definition: a set of interacting elements and actors that promote the creation of new businesses in a specific regional or local context (Mason and Brown 2014; Mack and Mayer 2016).

Accordingly, our framework underlines the complementarity and interdependence of the axes. Some studies are part of multiple axes. For example, the studies by Mason and Brown (2014) and Stam (2015) are part of both the systemic axis and the spatial axis, whereas the study of Auerswald and Dani (2017) is part of both the evolutionary axis and the spatial axis. While it is consistent with the spatial axis, an international perspective of the entrepreneurial ecosystem could appear to be in opposition to this axis. However, an international lens may enhance and broaden our understanding of the entrepreneurial ecosystem. The following section presents an international perspective of this ecosystem.

2.2 Internationalizing the entrepreneurial ecosystem

Internationalization is considered a time-based process of entrepreneurial behavior (Jones and Coviello 2005; Prashantham et al. 2019). It is increasingly seen as crucial for the survival, growth and long-term viability of businesses, particularly SMEs (Bannò et al. 2014). As a result, most governments have developed policies that support the internationalization process of their companies. These are defined as “government measures that help indigenous firms perform their export activities more effectively” (Leonidou et al. 2011, p. 4). Currently, in the context of limited public finance, the performance of entrepreneurial support tools, including those dedicated to international activities, has become a crucial issue (Parker 2007; Messeghem et al. 2018; Theodoraki et al. 2020).

Several studies focus on the link between internationalization support and firm performance (Leonidou et al. 2011, 2014; Bannò et al. 2014). Felzensztein et al. (2015) suggest that this type of support accelerates the internationalization process and is likely to improve the international performance of SMEs (Hilmersson and Johanson 2016). Support related to reducing risk appears to be particularly relevant for small firms that have fewer resources and thus experience high levels of risk in the context of internationalization (Musteen et al. 2010). Other studies demonstrate that internationalization support has a positive influence on performance and should thus be integrated into companies’ strategic thinking (Catanzaro and Teyssier 2020). However, it is less obvious which ecosystem characteristics have the greatest impact on the international success of companies (Love and Roper 2015). Hence, evidence regarding the success and functioning of an ecosystem dedicated to internationalization support is lacking. Thus, to create sustainable economic development, it is necessary to balance the dynamics of the entrepreneurial ecosystem, various actors’ collaboration and rivalries, and support initiatives (Felzensztein et al. 2019).

In France, policies that support the internationalization process have been established, leading to the emergence of an entrepreneurial ecosystem characterized by internationalization support, which is also called an internationalization support ecosystem (ISE). This ecosystem brings together public and private actors who are organized at the regional level according to the Regional Economic Development, Innovation and Internationalization Schemes (SRDEIIs). These regional ecosystems are intended to pool the tools and resources that all the involved partners make available to companies, facilitating the development, deployment and monitoring of an effective international strategy. Thus, like the entrepreneurial ecosystem in general, the internationalization support ecosystem is the result of an entrepreneurial territorial strategy (Acs et al. 2017; Audretsch and Belitski 2017). On the other hand, the spatialization of this ecosystem (spatial axis) challenges the traditional approach, which is centered exclusively on territories. Indeed, the ecosystem’s international perspective is not limited to its mission, i.e., to support companies abroad. The internationalization support ecosystem is based not only on local anchoring but also on the necessary international integration through a set of international actors or local members that have branches abroad. Thus, its very structure (structural axis) tends towards a different approach that integrates an international perspective. Similarly, the strategic interactions and social capital of this ecosystem (systemic axis) have a certain “international” nature in more than one aspect: the ecosystem’s network of members reaches beyond its original territory, the support process involves international actors and international actions, and the provided support involves access to international networks and resources. Catanzaro et al. (2019) also demonstrate that one of the major contributions of internationalization support is the strengthening of a company’s international relational capital through an international network of ecosystem members.

All these characteristics of the international perspective allow us to highlight a fifth axis from the literature on entrepreneurial ecosystems, namely, an international axis (Table 1). We propose that its attributes and contribution to the modeling of entrepreneurial ecosystems should be explored according to each of the other axes.

3 Methods

3.1 Research design

This section describes our exploratory qualitative case study of the French internationalization support ecosystem (Yin 2018), which is considered in this study one of the sub-ecosystems of the broader entrepreneurial ecosystem. This approach is appropriate for studying how research questions, which are especially applicable in this case as the ecosystem literature is in an early stage of development (Dana and Dana 2005). The French context was chosen because it contains all the elements of an entrepreneurial ecosystem as described by Cohen (2006), i.e., favorable entrepreneurial governance and financial aid, universities, support actors, international firms, an entrepreneurial culture and a history of entrepreneurship. Additionally, it is thought to have a particularly dynamic environment that is influenced by the strong evolution of its laws and traditions. Until recently, the internationalization support ecosystem focused exclusively on public organizations. However, the creation of the Team France ExportFootnote 2 in 2008 (which was comprehensively reformed in 2018) and the launch of the Regional Economic Development, Innovation and Internationalization Schemes (SRDEIIs) in 2014 enabled the entrepreneurial ecosystem to expand to include private actors. Since then, partnership agreements at the local and national levels have been signed by both sectors (e.g., the OSCIFootnote 3—Business FranceFootnote 4 agreement in 2016), allowing public and private actors to work together to increase the effectiveness of their support for companies. With the 2018 reform of Team France Export, a twofold objective was introduced: (1) Set up a simple and legible system for companies: a one-stop shop at the regional level with a single Team France Export correspondent abroad; (2) Offer even more effective support through the strengthening of the public service resources in the region and the involvement of private experts.

In this context, four actors with regional relays occupy a predominant place: (1) the International Chambers of Commerce and Industry (CCI), (2) Business France, (3) Bpifrance and (4) a private actor, namely, OSCI, which is a federation of international trade entrepreneurs. Regional CCIs play a central role because a company that wishes to benefit from the support of its regional ecosystem must first accepted by a CCI international development advisor. The latter is generally a specialist in the given company’s sector of activity and/or its targeted geographical area. This advisor plays the role of an intermediary or “broker” that is responsible for connecting the company with other public and private actors in the ecosystem according to its specific needs. The advisor also provides the company first-hand information regarding the internationalization process and targeted countries and proceeds with the activation of the network of private partners if necessary.

More operational support (networking, participation in trade fairs and prospecting missions) is provided by Business France. Financial support services (loans, grants, guarantees and insurance) are provided by Bpifrance. Private banks have their own support products, and some banks (e.g., BNP Paribas) work directly with Bpifrance. Some regions also provide financial support to their companies, mainly when they operate in a sector considered strategic by the territory. Within this network, private actors are mobilized throughout the support process according to each company’s problems and needs, especially when they face complex situations (regulatory constraints, opaque markets, etc.). Private actors who are members of OSCI enjoy greater legitimacy among public actors, particularly through existing formal partnerships. Finally, there are relays abroad, both public (Business France operators) and private (partner consultants and subsidiaries of French private organizations), which can provide additional expertise due to their facilitated access to targeted foreign markets.

3.2 Data collection

The data collected comprise twenty semi-structured interviews conducted using an interview guide (see Appendix). Semi-structured interviews are very flexible because they allow us to discuss one topic before or after another topic depending on each respondent’s sequence of ideas. We adapted the interview guide to each actor’s profile, particularly on a public/private basis. The interview guide included questions on the support practices (services and methods), evolution (changes, adaptation, and business perceptions), impact (support influence, performance, satisfaction, and improvements) and ecosystem interactions (relations with other actors) of the actors.

Table 2 lists the interviews conducted and recorded, specifying the organization, position and duration of each interview. Ten of the participants interviewed belong to actors in the public sphere and ten others to actors in the private sphere; however, the three French foreign trade advisors (CCEFs) interviewed navigate between these two worlds, as does the cluster to some extent because its governance structure is financed by both private and public funds. These participants were asked about the following two functions: their public missions as foreign trade advisors and their private roles as consultants when suitable. The interviews took place between February and July 2018. The package includes 20 h and 41 min of interviews.

3.3 Data analysis

The interviews were transcribed into a total of 386 pages. To analyze this corpus, as well as the additional documents and reports collected from the institutional sites of the interviewed participants, we conducted a thematic analysis (Miles and Huberman 1994). This approach made it possible to find recurring themes within the various documents and interviews that comprised the corpus and related content. To do this, we chose a horizontal approach, i.e., a transversal analysis that consists of identifying recurrences and regularities in the various documents of a corpus. Thus, the coherence of the analysis no longer depended on the individual structure of each document or interview but on all the comparable elements of the documents.

However, a thematic analysis is not restricted to a summary of the examined data; rather, it allows us to interpret the data and give meaning to them. A common pitfall of this method is to use the main interview questions as analyzed themes, which results in an organized summary of the data rather than a data analysis (Clarke and Braun 2013). Thus, we opted to use posteriori coding, i.e., our coding method was determined and constructed after the documents were analyzed. This less direct approach was well suited to the exploratory nature of our research.

We collected additional resources about the examined support players from websites, public reports, and articles. This multiplicity of data sources allowed us to apply a triangulation method to actively and consciously attempt to support, cross-check and corroborate the results of this study (Gibbert et al. 2008). Finally, in terms of external validity, the results of our research were discussed and validated by the members of the board and scientific council of Think Tank La Fabrique de l’Exportation,Footnote 5 which are composed mainly of the members of OSCI, Bpifrance and CNCCEF (National Committee of French Foreign Trade Advisors).

4 Findings

The aim of this research was to enrich the traditional approach to examining the entrepreneurial ecosystem by adding an international perspective (see Table 3). In doing so, we analyzed our data through the lens of the four axes identified in the literature.

4.1 Structural axis

Our analysis was intended to identify the elements, links and roles of the actors involved in internationalization support, including those located abroad. The French ISE has often been characterized as complex with an increasing lack of visibility because of the millefeuille of the involved actors and offers. Recently, to address this challenge, there has been a major reorganization of the entrepreneurial ecosystem, encompassing (1) the emergence of Business France, which was born from the merger between the French Agency for International Investment and Ubifrance; (2) the establishment of Bpifrance and its export branch (formerly OSÉO); and (3) the absorption of the Coface system into the insurance division of Bpifrance. In addition to its reorganization into regional networks, the CCI International network has strengthened its role in the ecosystem by trying to position itself as a one-stop shop with the ability to redirect companies towards various actors and support according to its needs. The regions' governments now play the role of coordinator within their territories according to the SRDEIIs. “What we wanted was something that brought fluidity between the partners”, according to the member of DIRECO that we interviewed.

Figure 1 provides a map of the main ISE actors. The actors who have a physical presence in France and representatives in the region are in the large circle. Those who are present abroad, some of which are present both in France and abroad (via satellite offices for public actors or subsidiaries for private actors), are in the small circle. The actors in boldface are public and parastatal actors, while those in italics are actors in the private sphere; finally, the dashed circle contains private players. For example, the ISE includes both public and private incubators. The arrow in the center of the diagram is intended to highlight the formalization of the partnerships between various public and private actors. This connection between the two sides of the private/public support ecosystem is intended to strengthen their collaboration and create more bridges that enable companies to obtain support from different actors according to their needs.

Internationalization support actors. AFD: Agency French Development/DEEI: Directorate of Business and International Economy/SAI: Internationalization Support Organizations/SGE: Export Management Companies/SCI: International Trading Companies/CCIFI: French CCI based abroad/OSCI: Entrepreneurs’ Federation of International Trade

The convenient one-stop shop is at the heart of the 2018 reform of the entrepreneurial ecosystem, and the notion of local collaboration between public and private actors has in fact already existed for a long time in some territories (it was introduced “about thirty years ago” according to one interviewee); indeed, from the perspective of many of the interviewed participants, has proven its effectiveness. The 2018 reform of Team France Export legitimizes the concept of a one-stop shop in the region with a single Team France Export correspondent abroad.

The CCIs are intended to play the roles of entry points and “complete system integrators”. “It is true that the network of CCIs—and we claim it, we display it without any concern in relation to the other actors—is ideally placed to be the privileged entry point for companies” (CCI). The objective is then “to know, as precisely as possible, all the actors who can meet all the demands of the companies; that is our knowledge. When I say, ‘network gateway’, that’s it” (CCI). Some even call for “creating a kind of continuum with counters abroad”. The French CCIs abroad play a similar role in providing support within the targeted countries. In addition to these entry points, there is a more coherent and coordinated support ecosystem involving the various operators.

In summary, the French ISE involves both public and private players; some are located in the territory of the ecosystem and others are located abroad but directly connected with the region and the companies within it. All these actors interact and work together to provide better support to local companies in regard to their global exploration.

4.2 Systemic axis

Regarding our international focus, the systemic axis characterizes the system of actors who support companies during their internationalization process and their interactions with system members located abroad. The ambition behind the reform of Team France Export was to develop a local support system that would involve all the relevant public and private actors as well as the actors located abroad. Consequently, in the French context, all relevant players are connected to the regional scope and form a strategic council that makes strategic decisions regarding the internationalization support of local companies, including those regarding the opportunities provided by their partners abroad. Thus, this regional council is responsible, according to the SRDEIIs, for coordinating the internationalization support policy of its territory. This policy aims to strengthen the collaboration between the various involved public actors to avoid duplication of efforts and, ultimately, to increase the effectiveness of the support provided to companies. It also aims to facilitate the relations among private actors. This approach is well perceived by the various relevant organizations because it allows them to “get around the table, study files together, share information and be able to work together to achieve common objectives for the company because all this is for the good of the company; so, it is important to coordinate” (CCEF).

However, we noted discrepancies among the examined regions, as they exhibit very different degrees of collaboration and sharing. “There are really 3 levels of integration (of SRDEII), which are still significantly different, and our relationship with the regional advisors is very different. Typically, here in Pays de la Loire, our strategic interlocutor is in the region; in Normandy, it is the Development Agency for Normandy, and in Brittany, it is obviously Brittany International Trade” (BF). Depending on its region, there are different people to whom a company may turn; the coordination among these people is not always perfect, and, from the companies’ perspective, this can sometimes lead to a lack of clarity within the entrepreneurial ecosystem. Overall, the SRDEIIs are well received by the interviewed public actors. On the other hand, their reception by the private actors is much more ambivalent. However, in some regions, a few private actors are involved in the conceptualization and implementation of relevant actions, and most actors consider the single-entry point “contrary to the objective of diversity of private provision”. Thus, the private actors selected by the region’s government remain as the main involved parties, to the detriment of the other private actors.

Consequently, the private sector is now involved in this process both before and after the public intervention and is able, according to the Director General of Business France, to “develop its service offer in a spirit of complementarity and relaying public action”. Therefore, this public/private partnership can be established at any stage of the process, from “sourcing companies and identifying companies with potential in France to projecting them onto the foreign market” (BF). The public actors recognize that “there are two kinds of private people for us. There are those who do the same thing as us, and indeed, it can sometimes be difficult” (BF). However, the private players who are complementary to the public players are valuable because they can intervene at any stage. The perspective of some of the private actors reflects that of the public actors: “In Business France, I have been thinking for a long time that they (public actors) should not be considered competitors” (private). Nevertheless, the public sector’s feeling of openness and collaboration towards the private sector seems less significant in practice: “We say that the private sector works with the public sector because I think the government has understood that everyone should be put in the same basket. However, if we look at the last press release from the inter-ministerial development meeting, we never talked about the OSCI (private actor). The term OSCI is not there, whereas we were the OSCI representatives at that meeting; we were there. However, we are not in it” (private). Nevertheless, it should also be noted that private actors (especially those of a certain size) prefer, if they have a choice, to work with private partners who share the same business vision and language and who are more accessible and sustainable.

4.3 Evolutionary axis

Through an international lens, the evolutionary axis comprises the specific evolution of the internationalization support process and the collaborations among the public players, private players, and members located abroad within this process. According to our interviewees, several stages of support are provided by the public sector, following a support process path. First, the support actors seek to diagnose a given company’s export capacity. This generally consists of an interview with the CCI’s international development adviser who enables a determination of the company’s strengths and weaknesses and an analysis of whether the company has sufficient resources to initiate the internationalization process. Once this potential has been determined, it is necessary to collect information on two or three potential foreign target countries to analyze them at the macro-, meso- and microeconomic levels (regarding their economic situation, their political stability, the state of the relevant industry, their customer needs, the necessary adaptations, etc.). This process is followed by an offer comprising various forms of training that is tailored to the company’s needs (customs procedures, Incoterms,Footnote 6 intercultural management, country information days, etc.).

The objective of these first three steps is to give the company the necessary information resources to define its strategy and launch itself internationally. The company is then able to prospect the identified markets by participating in trade shows, prospecting missions, and networking events. During this phase, ISE members located abroad are particularly useful, as they help the firm identify and meet the key players who will enable them to record their first sales in the target territory. In addition, the firm may receive funding if necessary. This sometimes comes from subsidies; however, when a given company meets the established criteria, it is more often provided by export loans, and very often provided by insurance that protects against the various risks linked to international activity. Once these steps have been successfully completed, the resulting support can help the company strengthen its presence in a target country and/or canvass new foreign markets.

Among private actors, the approach is different. These actors can be directly involved in the abovementioned approach by participating at its different stages depending on the degree of complexity involved or simply the time at which the involved public actor prefers to delegate to a private actor. For example, many regional CCIs engage private consultants to conduct the first step of the diagnosis of the company’s “export capacity assessment”. Sometimes, the provided training requires very specific knowledge that necessitates the support of private actors. In other situations, Business France or CCI offices abroad commission private actors to carry out certain tasks (market studies, legal analyses, etc.). In the private support market, when a company addresses these actors directly without going through the public sector, the notion of “support process paths” does not apply. In this case, companies obtain the services that they need when they need them. It is possible for public actors to adopt this free and personalized approach but to a lesser extent. According to the President of the OSCI, the support provided by private actors is based on the following solutions: (1) Consulting expertise solutions designed to prepare companies for internationalization, including strategy, marketing, and organization consulting and local HR solutions. (2) Prospecting for assistance services including market research, the organization of meetings and follow-up negotiations with prospects, recruitment, coaching and employee accommodation. (3) Services related to companies’ industrial or commercial establishments in their target countries, including incubation, management of subsidiaries on the behalf of third parties, operational services related to distribution and after-sales service, economic intelligence, and mergers and acquisitions. (4) Total or partial outsourcing of the export process, including outsourced export managers and sales representatives, timeshare sales staff, export agents, export management companies, export via international trading companies, and product distribution. (5) Services related to supply optimization, including sourcing and delegated import management.

The overlap between this approach and the public offer (particularly in terms of diagnoses, advice and preparation) shows that the expertise of private actors on substantially similar offers is more extensive. A public actor may be powerless to deal with certain requests or complex situations, while a private actor, thanks to its network of partners abroad, will be able to provide precise answers. Moreover, a private actor, unlike a public one, can engage in targeted operational approaches on behalf of a given company, both in the company’s domestic market and in its targeted foreign markets. In this sense, all other things being equal, a private actor is better able to intervene downstream of a given company’s internationalization process.

4.4 Spatial axis

The spatial axis allows us to broaden the entrepreneurial ecosystem concept beyond geographical perimeters; indeed, territorial characteristics are determinants of the internationalization support strategy of the examined region. Our analysis leads us to describe the glo-cal culture of the entrepreneurial ecosystem that combines local anchoring and global approaches and broadens the traditional approach of the spatial axis. Indeed, links with actors based abroad (public actors abroad such as Business France or French CCIs; private actors such as partner consultants or subsidiaries of French operators) are an integral part of the regional ecosystem. In the absence of these actors, the entire entrepreneurial ecosystem would be affected because its mission, namely, to support companies in their international endeavors, would then be deprived of certain elements that are essential to its success and sustainability.

Ecosystem members based abroad are sources of information, opportunities, expertise and relationships. By being as close as possible to foreign markets, they bring valuable market knowledge to regional ecosystems that can only be acquired by being present in foreign countries. In fact, overseas contacts are sources of opportunities that can benefit supported companies, as confirmed by our Business France CCEF interviewee: “We are talking about entrepreneurial strategy, products, added value, and distribution channels, and then the business plan and the means we have in front of us. That’s really what it is. You tell me: ‘I don’t know where I’m going yet, I have to get an idea’, so that’s why we have the possibility of opening up access to these types of experiences and interviews, which allows, in a peer-to-peer interview, the company to grasp what it’s looking for” (CCEF). The support process is also strongly impacted by the global aspect of the ecosystem since the members based abroad complement the actors located in the region. For example, Business France operators abroad come to the region to participate in training on international business practices delivered in a territorial CCI. They also provide some support when companies reach a certain stage of their operational development. A company can then be received, on site, by ecosystem members who are established in the company’s target market and benefit from this support, in addition to that received in France. At an intermediate level, the supported companies may also be satisfied with using the services of these members without having to travel. Notably, a member’s enrollment in the ecosystem allows such a company to benefit from advantageous rates, known as “public” rates, with public actors, or from partial coverage by a public subsidy. In other words, working with a private support company disconnected from the ecosystem will be more expensive for supported companies.

In terms of relationships, members located abroad benefit from a local network that is extremely valuable for the ecosystem and the companies that it supports. Whether formal or informal, personal or business, the network of these members abroad is very complementary to that of the members located in the domestic region. These networks and contacts are the main contribution of the ecosystem to the supported companies, according to most of our interviewees. For example, an interviewee from a private actor stated that “One of the big strengths of the private network is the anchor in the network, in the sense that it’s our capital, our know-how” (private consultant), while an interview from a public actor claimed that “We help the firm to work networks locally, once again in its region, and then internationally in the country where it (the company) wishes to establish itself” (CCI).

Finally, the enlarged spatial axis of the ecosystem and its glo-cal culture are also reflected in the quest to enhance the value of the territory and its specific features at the international level. According to the SRDEIIs, the strategy of the regional ecosystem is defined by the region itself, in coordination with the various involved members. Thus, the members of the ecosystem adapt their strategy according to the regional economic fabric, the region’s strategic sectors, and the profiles of the region’s companies; this is evidenced by the statement of an international delegate from the Region of Bpifrance who claimed, regarding the characteristics of the region and its companies, that “quite significant actions for supporting the internationalization of agri-food companies” had been implemented. The characteristics of the territory influence the services provided by the ecosystem. Thus, the local level becomes a strong determinant of the international perspective of the ecosystem. For example, Sopexa, a communication and marketing agency with a worldwide reputation specializing in agri-food, participates in the strategic adaption of the abovementioned regional ecosystem. Some of the specific measures implemented in this region are intended to enhance the international reputation and notoriety of the region, the ecosystem and the companies involved in the agri-food sector.

5 Discussion

In this study, we argue that viewing the entrepreneurial ecosystem through an international lens contributes a new way of thinking regarding this emerging theoretical trend. Consequently, this study provides an answer to researchers who suggest that the entrepreneurial ecosystem is under-theorized and call for more theorization work in this field (Acs et al. 2017; Spigel and Harrison 2018). We devote the remainder of this section to the impacts of the international perspective in the context of the ISE, which is a sub-ecosystem of internationalization support. By structuring the entrepreneurial ecosystem literature based on four axes, namely, the structural, systemic, evolutionary and spatial axes, we identify a theoretical gap that due to its focus on regional development provides at best limited knowledge to the international perspective. To fill this gap, we enrich the model of the entrepreneurial ecosystem with a fifth axis, namely, an international axis (see Table 1).

5.1 Contributions to scholarship

As a contribution to the theoretical development of entrepreneurial ecosystems, we shed light on how an international perspective refines this concept and widens the boundaries of each of its structural axes. We observe that the internationalization support ecosystem enhances each identified axis with the intent of improving the international performance of local firms by facilitating their entry into foreign markets as a means to foster local economic development. Specifically, the structural axis is mainly focused on identifying the elements and actors that make up the entrepreneurial ecosystem. Isenberg (2011) proposes the first model of the entrepreneurial ecosystem and places entrepreneurship at its center. The researchers who examine the structural axis attempt to study the configuration of the entrepreneurial ecosystem and propose different models for it. Our international lens is intended to complement this work within the context of internationalization support.

This work enhances the previous models by applying them in a different context. The current research regarding the systemic axis focuses on the dynamic structure of the ecosystem and the interactions among the elements that foster entrepreneurship. According to Theodoraki et al. (2018), the entrepreneurial ecosystem consists of three interconnected dimensions: the structural, cognitive and relational dimensions. This model neglects the international dimension that refines the conceptualization of the entrepreneurial ecosystem. Recently, the evolutionary axis has been linked to the processes of entrepreneurial activity (Spigel and Harrison 2018). This new approach supports the idea of studying the entrepreneurial ecosystem as an evolutionary phenomenon and not a static one. The international perspective opens a debate on a new topic in the context of the process of internationalization support. We propose that the internationalization of companies should be one of the major objectives of the entrepreneurial ecosystem. However, this concept has been neglected so far.

In addition, the spatial axis enhances the territorial anchoring of the entrepreneurial ecosystem, which is concerned with establishing entrepreneurial strategies according to the specific attributes of individual territories that are adapted to support the proper functioning of the ecosystem. However, integrating this axis with an international perspective makes it possible to enhance this goal by offering flexibility in terms of the strict boundaries utilized by the existing entrepreneurial ecosystem studies. Thus, the articulation between, on the one hand, local ecosystems and territorial anchoring and, on the other hand, an international perspective of the entrepreneurial ecosystem leads us to support the concept of a glo-cal (global–local) culture within this ecosystem. In another context, Carayannis and von Zedtwitz (2005) highlight incubators’ interest in adopting a glo-cal approach by integrating various private and public entities from different countries to better support the creation of innovative companies. Consequently, a glo-cal culture within the internationalization support ecosystem should contribute to supporting the internationalization of companies.

Moreover, our results lead us to defend the approach of considering the internationalization support ecosystem a sub-ecosystem of the regional entrepreneurial ecosystem, which consists of the following different levels or sub-ecosystems: the macro level, which corresponds to the entrepreneurial ecosystem as a whole; the meso level, which refers to the sub-ecosystem of entrepreneurial support (for business creation); and the micro level, which focuses on the organizations belonging to the various sub-ecosystems (Theodoraki and Messeghem 2017). Furthermore, our results show that these sub-ecosystems interact, which is consistent with existing work related to this topic (Stam and van de Ven 2019). Indeed, our interviews underline that co-support exists between the sub-ecosystem of business creation and that of internationalization support, particularly in terms of start-ups that implemented internationalization strategies since their creation, which are called born global firms in the literature concerning international entrepreneurship (Cannone and Ughetto 2014). This situation is also obvious in the case of public and private players who co-support companies during the internationalization process in complementarity. These dynamics force the actors within the two sub-ecosystems to cooperate in meeting the very specific needs of these enterprises (Fig. 2).

5.2 Implications for practitioners and policymakers

The entrepreneurial ecosystem has become a powerful tool for policymakers who desire to build successful entrepreneurial societies that enhance business creation and foster local economic development. This study provides a novel model of the entrepreneurial ecosystem that is enhanced through the integration of an international perspective. This perspective extends the previous models that encourage economic development within local boundaries. This international context reveals another outcome from internationalization support organizations that support business creation beyond local boundaries and introduces added value from a circular inside-out and outside-in process. Thus, as a sub-ecosystem, the ISE should be further embedded into the structure of the entrepreneurial ecosystem. This study sheds light on the internationalization support ecosystem and how it is embedded into the broader entrepreneurial ecosystem. Internationalization support organizations may benefit from this perspective of the entrepreneurial ecosystem through being framed as part of the ecosystem and not as single entities.

Likewise, this research also provides insights for policymakers who make decisions on building a sustainable, efficient and healthy ecosystem. Internationalization support is defined as the process of strengthening a company’s resources and international performance (Catanzaro et al. 2019). Therefore, it represents a microeconomic approach to internationalization support. By examining this field of literature with an entrepreneurial ecosystem approach, we propose that a macroeconomic point of view is adopted to focus on the support actors and their practices. Accordingly, to extend the previous studies that focus on support services as determinants of a supported company’s performance, our research sheds light on the determinants of the entrepreneurial ecosystem’s efficiency, which can, in turn, be seen as the determinants of the effectiveness of the services themselves (Theodoraki et al. 2020). Lederman et al. (2010) point out that a support system organized around large and powerful organizations is more effective than a system composed of multiple small and disparate actors. Thanks to its reorganization, France developed a coherent dynamic ecosystem. Additionally, this knowledge enables the members of an entrepreneurial ecosystem to adapt and integrate their individual strategies into an effective long-term entrepreneurial development strategy for their territory.

5.3 Limitations and directions for future research

While the French context provided a fruitful field of research that can be compared to the situations in several other European countries, we acknowledge that the context and cultural specificities of this study had a major effect on the generalizability of our findings. The exploratory nature of this study resulted in the collection of a small number of interviews related to internationalization support in France. While our findings highlighted the importance of the international perspective in the context of extending the entrepreneurial ecosystem model, this study should be repeated in other countries and contexts to increase the generalizability of its results. For instance, we propose that this study is applied in other contexts so that different dimensions of the entrepreneurial ecosystem and how they are impacted by the international perspective can be addressed; additionally, the outcomes and challenges faced by widening the local boundaries should be examined. While our empirical results are derived from the cultural-specific context of France, further research should duplicate this study in emerging countries, investigating the role and importance of the internationalization support ecosystem (Xie et al. 2019).

Further investigation should be conducted in countries with different geographical characteristics, and a comparison across developed and developing economies should be performed (Guerrero et al. 2020). Indeed, it is important to determine whether the internationalization of entrepreneurial ecosystems plays the same role in small countries surrounded by other countries, i.e., the Netherlands, and large and relatively geographically isolated countries, i.e., Australia. This question reflects findings in the international business literature that stipulate that the size and location of the country influence the path of internationalization (Johanson and Vahlne 1977), facilitate international network establishments (Johanson and Vahlne 2011), and encourage companies to internationalize (Madsen and Servais 1997). Similarly, some international entrepreneurship studies show that small countries have more born global firms because of the size of their market. For example, companies in northern Europe are pushed very quickly to foreign markets due to the small size of their domestic market (Moen 2002). However, an American company has a large domestic market of more than 320 million inhabitants, which can delay the company’s start of internationalization (Sheppard and McNaughton 2012). From this perspective, one could expect the entrepreneurial ecosystem role in internationalization to differ according to the geographical features of the territory or country. The more the country is small and surrounded by other countries, the more its entrepreneurial ecosystems would have a tendency to internationalize to meet the needs of its firms. In contrast, an entrepreneurial ecosystem from larger markets could take time to develop internationally because of the sufficient local resources and opportunities for local companies. From this perspective, other determinants, such as historical links, could also play a role. Therefore, a contingency approach may provide a strong theoretical foundation. Future studies are needed to refine our analysis in different contexts.

Furthermore, while we attempted to examine the temporal effects of the ecosystem axes by investigating the interviewees’ past experiences and triangulating them with retrospective reports, a longitudinal study protocol could reveal different effects of and relationships among the ecosystem axes and the international perspective.

6 Conclusion

In conclusion, to address the gap in the literature involving limited empirical evidence for the importance of an international lens in understanding the entrepreneurial ecosystem, our study empirically explored the international dimension of the entrepreneurial ecosystem in the context of internationalization support. This work created a more rigorous and comprehensive theoretical framework for future research on entrepreneurial ecosystems and a structured logic of the related existing and future literature. Therefore, our study opens several avenues for future research, and we invite the academic community to adopt an international lens and a glo-cal approach to test the effectiveness of these concepts in other contexts. In addition, future research should examine the role of governance through an international lens. This context is conducive to studying the effectiveness of a “one-stop shop” for international business support. This specific type of governance does not seem to be effective in terms of ensuring the sustainability of the entrepreneurial ecosystem. Nevertheless, the work of Feld (2012) encourages the adoption of bottom-up governance practices, which are those promoted by the users, i.e., the supported companies.

Availability of data and material

Data used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

904 publications (674 journals, 129 books, 101 other types, i.e., conference proceedings), 91,7% of which were published or in press between 2016 and 2021 and 72,1% between 2018 and 2021—Scopus data consulted on January 4, 2021.

One-stop shop for internationalization support born from the collective ambition to bring together public and private actors to improve their export support.

OSCI: Entrepreneurs’ Federation of International Trade.

National agency created by a merger between Ubifrance and the French Agency for International Investment.

The Fabrique de l’Exportation is a Think Tank founded in France in 2012 and which aims to share the results of the work of the best researchers in this field with the international community of operators.

INTernational COmmercial TERMS.

References

Ács, Z. J., Autio, E., & Szerb, L. (2014). National systems of entrepreneurship: Measurement issues and policy implications. Research Policy, 43(3), 476–494.

Acs, Z. J., Stam, E., Audretsch, D. B., & O’Connor, A. (2017). The lineages of the entrepreneurial ecosystem approach. Small Business Economics, 49(1), 1–10.

Adner, R. (2017). Ecosystem as structure: An actionable construct for strategy. Journal of Management, 43(1), 39–58.

Alvedalen, J., & Boschma, R. (2017). A critical review of entrepreneurial ecosystems research: Towards a future research agenda. European Planning Studies, 25(6), 887–903.

Audretsch, D. B., & Belitski, M. (2017). Entrepreneurial ecosystems in cities: Establishing the framework conditions. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 42(5), 1030–1051.

Auerswald, P. E., & Dani, L. (2017). The adaptive life cycle of entrepreneurial ecosystems: The biotechnology cluster. Small Business Economics, 49(1), 97–117.

Autio, E., Nambisan, S., Thomas, L. D. W., & Wright, M. (2018). Digital affordances, spatial affordances, and the genesis of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 12(1), 72–95.

Bannò, M., Piscitello, L., & Varum, C. A. (2014). The impact of public support on SMEs’ outward FDI: Evidence from Italy. Journal of Small Business Management, 52(1), 22–38.

Brown, R., & Mason, C. (2017). Looking inside the spiky bits: A critical review and conceptualisation of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Small Business Economics, 49(1), 11–30.

Bruns, K., Bosma, N., Sanders, M., & Schramm, M. (2017). Searching for the existence of entrepreneurial ecosystems: A regional cross-section growth regression approach. Small Business Economics, 49(1), 31–54.

Cannone, G., & Ughetto, E. (2014). Born globals: A cross-country survey on high-tech start-ups. International Business Review, 23(1), 272–283.

Carayannis, E. G., & von Zedtwitz, M. (2005). Architecting gloCal (global–local), real-virtual incubator networks (G-RVINs) as catalysts and accelerators of entrepreneurship in transitioning and developing economies: Lessons learned and best practices from current development and business incubation practices. Technovation, 25(2), 95–110.

Catanzaro, A., Messeghem, K., & Sammut, S. (2019). Effectiveness of export support programs: Impact on the Relational capital and international performance of early internationalizing small businesses. Journal of Small Business Management, 57(2), 436–461.

Catanzaro, A., & Teyssier, C. (2020). Export promotion programs, export capabilities, and risk management practices of internationalized SMEs. Small Business Economics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00358-4.

Cavallo, A., Ghezzi, A., & Balocco, R. (2019). Entrepreneurial ecosystem research: Present debates and future directions. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 15(4), 1291–1321.

Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2013). Teaching thematic analysis: Overcoming challenges and developing strategies for effective learning. Psychologist, 26(2), 120–123.

Cohen, B. (2006). Sustainable valley entrepreneurial ecosystems. Business Strategy and the Environment, 15(1), 1–14.

Colombelli, A., Paolucci, E., & Ughetto, E. (2019). Hierarchical and relational governance and the life cycle of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Small Business Economics, 52(2), 505–521.

Colombo, M. G., Dagnino, G. B., Lehmann, E. E., & Salmador, M. P. (2019). The governance of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Small Business Economics, 52(2), 419–428.

Dana, L. P., & Dana, T. E. (2005). Expanding the scope of methodologies used in entrepreneurship research. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 2(1), 79–88.

Feld, B. (2012). Startup communities: Building an entrepreneurial ecosystem in your city. New Jersey: Wiley.

Felzensztein, C., Ciravegna, L., Robson, P., & Amorós, J. E. (2015). Networks, entrepreneurial orientation, and internationalization scope: Evidence from Chilean small and medium enterprises. Journal of Small Business Management, 53, 145–160.

Felzensztein, C., Deans, K. R., & Dana, L. P. (2019). Small firms in regional clusters: Local networks and internationalization in the Southern Hemisphere. Journal of Small Business Management, 57(2), 496–516.

Gibbert, M., Ruigrok, W., & Wicki, B. (2008). What passes as a rigorous case study? Strategic Management Journal, 29(13), 1465–1474.

Guerrero, M., Liñán, F., & Cáceres-Carrasco, F. R. (2020). The influence of ecosystems on the entrepreneurship process: A comparison across developed and developing economies. Small Business Economics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00392-2.

Hilmersson, M., & Johanson, M. (2016). Speed of SME internationalization and performance. Management International Review, 56(1), 67–94.

Isenberg, D. (2010). How to start an entrepreneurial revolution. Harvard Business Review, 88(6), 40–50.

Isenberg, D. (2011). The entrepreneurship ecosystem strategy as a new paradigm for economic policy: Principles for cultivating entrepreneurship. Dublin, Ireland: Institute of International European Affairs.

Isenberg, D. (2016). Applying the ecosystem metaphor to entrepreneurship: Uses and abuses. The Antitrust Bulletin, 61(4), 564–573.

Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J. E. (1977). The internationalization process of the firm: A model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitments. Journal of International Business Studies, 8(1), 23–32.

Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J.-E. (2011). Markets as networks: Implications for strategy-making. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(4), 484–491.

Jones, M. V., & Coviello, N. E. (2005). Internationalisation: Conceptualising an entrepreneurial process of behaviour in time. Journal of International Business Studies, 36(3), 284–303.

Jones, M. V., Coviello, N., & Tang, Y. K. (2011). International entrepreneurship research (1989–2009): A domain ontology and thematic analysis. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(6), 632–659.

Lederman, D., Olarreaga, M., & Payton, L. (2010). Export promotion agencies: Do they work? Journal of Development Economics, 91(2), 257–265.

Leonidou, L. C., Palihawadana, D., & Theodosiou, M. (2011). National export-promotion programs as drivers of organizational resources and capabilities: Effects on strategy, competitive advantage, and performance. Journal of International Marketing, 19(2), 1–29.

Leonidou, L. C., Samiee, S., & Geldres, V. V. (2014). Using national export promotion programs to assist smaller firm’s international entrepreneurial initiatives. In V. M. Kirpalani & P. N. Ghauri (Eds.), Handbook of research on international entrepreneurship (pp. 233–267). Cheltenham: Elgar Online Publishing.

Love, J. H., & Roper, S. (2015). SME innovation, exporting and growth: A review of existing evidence. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 33(1), 28–48.

Mack, E., & Mayer, H. (2016). The evolutionary dynamics of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Urban Studies, 53(10), 2118–2133.

Madsen, T. K., & Servais, P. (1997). The internationalization of Born Globals: An evolutionary process? International Business Review, 6(6), 561–583.

Malca, O., Peña-Vinces, J., & Acedo, F. J. (2019). Export promotion programmes as export performance catalysts for SMEs: Insights from an emerging economy. Small Business Economics, 55(3), 831–851.

Malecki, E. J. (2018). Entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial ecosystems. Geography Compass, 12(3), e12359.

Mason, C., & Brown, R. (2014). Entrepreneurial ecosystems and growth oriented entrepreneurship. The Hague, Netherlands: OECD Workshop-LEED Programme and the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs.

McGaughey, S. L., Kumaraswamy, A., & Liesch, P. W. (2016). Institutions, entrepreneurship and co-evolution in international business. Journal of World Business, 51(6), 871–881.

Messeghem, K., Bakkali, C., Sammut, S., & Swalhi, A. (2018). Measuring nonprofit incubator performance: Toward an adapted balanced scorecard approach. Journal of Small Business Management, 56(4), 658–680.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. London: Sage.

Moen, Ø. (2002). The born globals: A new generation of small European exporters. International Marketing Review, 19, 156–175.

Morris, M. H., Neumeyer, X., & Kuratko, D. F. (2015). A portfolio perspective on entrepreneurship and economic development. Small Business Economics, 45(4), 713–728.

Musteen, M., Francis, J., & Datta, D. K. (2010). The influence of international networks on internationalization speed and performance: A study of Czech SMEs. Journal of World Business, 45(3), 197–205.

Nambisan, S., Zahra, S. A., & Luo, Y. (2019). Global platforms and ecosystems: Implications for international business theories. Journal of International Business Studies, 50(9), 1464–1486.

Neumeyer, X., & Santos, S. C. (2018). Sustainable business models, venture typologies, and entrepreneurial ecosystems: A social network perspective. Journal of Cleaner Production, 172, 4565–4579.

Neumeyer, X., Santos, S. C., & Morris, M. H. (2019). Who is left out: Exploring social boundaries in entrepreneurial ecosystems. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 44(2), 462–484.

O’Kane, C., Cunningham, J. A., Menter, M., & Walton, S. (2020). The brokering role of technology transfer offices within entrepreneurial ecosystems: An investigation of macro–meso–micro factors. The Journal of Technology Transfer. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-020-09829-y.

Parker, S. C. (2007). Policymakers beware. In D. B. Audretsch, I. Grilo, & A. R. Thurik (Eds.), Handbook of research on entrepreneurship policy (pp. 54–63). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Pitelis, C. (2012). Clusters, entrepreneurial ecosystem co-creation, and appropriability: A conceptual framework. Industrial and Corporate Change, 21(6), 1359–1388.

Porter, M. E. (2000). Location, competition, and economic development: Local clusters in a global economy. Economic Development Quarterly, 14(1), 15–34.

Prashantham, S., Kumar, K., Bhagavatula, S., & Sarasvathy, S. D. (2019). Effectuation, network-building and internationalisation speed. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 37(1), 3–21.

Roundy, P. T., Bradshaw, M., & Brockman, B. K. (2018). The emergence of entrepreneurial ecosystems: A complex adaptive systems approach. Journal of Business Research, 86, 1–10.

Ryan, P., Giblin, M., Buciuni, G., & Kogler, D. F. (2020). The role of MNEs in the genesis and growth of a resilient entrepreneurial ecosystem. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2020.1734260.

Schwens, C., Zapkau, F. B., Bierwerth, M., Isidor, R., Knight, G., & Kabst, R. (2018). International entrepreneurship: A meta-analysis on the internationalization and performance relationship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 42(5), 734–768.

Sheppard, M., & McNaughton, R. (2012). Born global and born-again global firms: comparison of internationalization patterns. In M. Gabrielsson & V. H. Kirpalani (Eds.), Handbook of research on Born Globals (pp. 46–56). Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Spigel, B. (2017). The relational organization of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(1), 49–72.

Spigel, B., & Harrison, R. (2018). Toward a process theory of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 12(1), 151–168.

Stam, E. (2015). Entrepreneurial ecosystems and regional policy: A sympathetic critique. European Planning Studies, 23(9), 1759–1769.

Stam, E., & Spigel, B. (2017). Entrepreneurial ecosystems. In R. Blackburn, D. D. Clercq, J. Heinonen, & Z. Wang (Eds.), Handbook for entrepreneurship and small business (pp. 407–422). London: Sage.

Stam, E., & van de Ven, A. (2019). Entrepreneurial ecosystem elements. Small Business Economics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00270-6.

Theodoraki, C., & Messeghem, K. (2017). Exploring the entrepreneurial ecosystem in the field of entrepreneurial support: A multi-level approach. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 31(1), 47–66.

Theodoraki, C., Messeghem, K., & Audretsch, D. B. (2020). The effectiveness of incubators’ co-opetition strategy in the entrepreneurial ecosystem: Empirical evidence from France. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEM.2020.3034476.

Theodoraki, C., Messeghem, K., & Rice, M. P. (2018). A social capital approach to the development of sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems: An explorative study. Small Business Economics, 51(1), 153–170.

Thompson, T. A., Purdy, J. M., & Ventresca, M. J. (2018). How entrepreneurial ecosystems take form: Evidence from social impact initiatives in Seattle. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 12(1), 96–116.

Tsujimoto, M., Kajikawa, Y., Tomita, J., & Matsumoto, Y. (2018). A review of the ecosystem concept towards coherent ecosystem design. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 136, 49–58.

van Weele, M., van Rijnsoever, F. J., Eveleens, C. P., Steinz, H., van Stijn, N., & Groen, M. (2018). Start-EU-up! Lessons from international incubation practices to address the challenges faced by Western European start-ups. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 43(5), 1161–1189.

Velt, H., Torkkeli, L., & Saarenketo, S. (2018). The entrepreneurial ecosystem and born globals: The Estonian context. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 12(2), 117–138.

Xie, X., Xie, X., & Martínez-Climent, C. (2019). Identifying the factors determining the entrepreneurial ecosystem of internet cultural industries in emerging economies. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 15(2), 503–522.

Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research: Design and methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the participants of the AOM Virtual Annual Conference on August 7-11, 2020 for their inspiring feedback and valuable suggestions.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: interview guide

Appendix: interview guide

Introductory questions | What is your objective and your role? |

Tell me about your support structure | |

Support services | 1. Could you tell me about the international support that you are offering? What type of support is it? |

Support methods | 2. How does international support work? |

3. When does your organization intervene to support a potential entrepreneur internationally? | |

Support influence | 4. In your opinion, what does your support offer companies? |

Support adaptation/evolution | 5. Do you have a single method of support, a process, or a way of doing things, or do you adapt your support according to the profile of a given company? |

Support performance | 6. In your opinion, what is the contribution of your support? What is its impact on the supported companies? |

7. What do you think are the key factors of successful coaching? | |

8. Do you evaluate your proposed practices/services? If so, how? | |

Offer satisfaction and improvement | 9. Are you satisfied with the way your support is structured? |

10. What developments would you like to see in the future? | |

11. Are you satisfied with the way in which the global offer of international support in France is structured? | |

Relations with other actors | 12. Do you work with other private actors? |

13. How is your relationship with other public/private actors? How is your relationship with actors based abroad? | |

14. How do you perceive the national support system? | |

Business perception | 15. How do companies perceive your offer? How do they perceive the latest developments of “the French export team”? |

16. Are they aware of your offer? Are they aware of the developments of the team? | |

Concluding comments | Are there any points that we have not addressed that you think are important to highlight? |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Theodoraki, C., Catanzaro, A. Widening the borders of entrepreneurial ecosystem through the international lens. J Technol Transf 47, 383–406 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-021-09852-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-021-09852-7

Keywords

- Entrepreneurial ecosystem

- Entrepreneurial support

- Internationalization

- International perspective

- Glo-cal culture