Abstract

The analysis of knowledge as an economic good has paid much attention to its limited appropriability. Lesser attention has been paid to its limited exhaustibility. The implications of the limited exhaustibility of knowledge is most important both for economics and economic policy. The effects of the limited exhaustibility of knowledge may compensate the effects of its limited appropriability. The Arrovian knowledge market failure takes place only when and if the downward shift of the intertemporal derived demand for non-exhaustible knowledge engendered by the limited appropriability of knowledge and the consequent decline of the price of innovated goods is larger than the downward shift of the intertemporal derived demand of standard capital goods engendered by their obsolescence. The appreciation of the joint effects of the limited exhaustibility of knowledge and of the knowledge appropriability trade-off calls for the design of a new knowledge policy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Arrow (1962) has paved the way to the economics of knowledge introducing the comparative analysis of knowledge as a public good. The Arrovian approach enabled to highlight the crucial differences between knowledge and standard economic goods, to implement an articulated analysis of their effects and to design public policy interventions aimed to contrasting their shortcomings.

The attention of the literature has focused the limited appropriability of knowledge and has stressed its implications in terms of the market failure stemming from the lack of appropriate incentives to allocate the correct amount of resources in its generation. The broadening of the analysis of knowledge as an economic good enables to unveil, next to its limited appropriability, other idiosyncratic characteristics that may have countervailing effects.

As a matter of fact, and quite surprisingly, much less attention has been paid to another key characteristics of knowledge: its limited exhaustibility. The analysis of its implications, beyond the focus on its effects in terms of increasing returns and monopolistic power, has not received the necessary attention. The role of the limited exhaustibility of knowledge as a countervailing factor of its limited appropriability deserves careful investigation.

The rest of this essay is organized as it follows. Section 2 explores the actual conditions of the exhaustibility of knowledge as an economic good. Section 3 applies the tools of the derived demand to explore in isolation the effects of the limited exhaustibility of knowledge on its demand and supply. Section 4 extends the framework to assess jointly the effects of its limited appropriability and exhaustibility. The conclusions summarize the implications of the analysis for economics and economic policy.

2 The exhaustibility of knowledge

So far the economic literature has identified the limited exhaustibility of knowledge only as an intermediary input in the generation of new knowledge. A large consensus has been encapsulated in the well-know Newton’s quote: “if I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders [sic] of Giants”. The extended duration of knowledge as an input in the generation of further knowledge has been implemented with the notion of knowledge cumulability. The literature has appreciated its positive effects in terms of economic growth at the system level and creation of barriers to entry and market power at the firm level.

The new growth theory has acknowledged the positive role of the accumulation of knowledge on growth stressing the increasing returns at the system level that stem from the cumulability of knowledge. Romer (1990) and Grossman and Helpman (1994) assume that, at the system level, the past experience of R&D accumulates in pools of quasi-public knowledge so that the unit costs of further R&D decline. Aghion and Howitt (1992) assume that long run growth depends upon the technological competence acquired in past research activities and made available at the system level by knowledge spillovers.

The resource based theory of the firm identifies in the accumulation of knowledge the basic element of the bundle of resources that defines a firm (Penrose 1959; Kogut and Zander 1992). Along the same lines, the evolutionary literature has highlighted the intrinsic cumulativity of knowledge as a key factor of the long-term competitive advantage of innovators in product markets stressing the role of knowledge cumulatibity as a major source of barriers to entry and asymmetric profitability (Dosi 1988).

The technology management literature has identified the cumulativity of knowledge as the key element that accounts for the persistence of innovativity: firms that have been able to build up a knowledge base are more likely to remain innovators in the long term, especially if the strength of their internal knowledge base is complemented by the effective access to pools of external knowledge cumulated by means of knowledge spillovers. As Teece (2000: 37) notes: “Technology developments, particularly inside a particular paradigm, proceeds cumulatively along a path defined by the paradigm. The fact that technological progress builds on what went before, and that much of it is tacit and proprietary, means that it usually has significant organization-specific dimensions. Moreover, an organization’s technical capabilities are likely to be close to the previous technological accomplishments”.

Recent advances in the economics of knowledge have stressed the role of the stock of existing knowledge as a necessary input in the recombinant generation of new knowledge. As Arthur notes: “I realized that new technologies were not ‘inventions’ that came from nowhere. All the examples I was looking at were created-constructed, put together, assembled-from previously existing technologies. Technologies in other words consisted of other technologies, they arose as combinations of other technologies” (Arthur 2009:2).

In this literature the emphasis on the role of the internal accumulation of knowledge is more and more complemented by appreciation of the central role of the accumulation of external stocks of quasi-public knowledge (Antonelli et al. 2015; Antonelli and Crespi 2013).

The relevant duration of patent terms—20 years in the European Union and in the United States—can be considered a reliable clue of the current consensus about the limited exhaustibility of knowledge and the extended duration of its economic value.

The economic literature has little investigated the broader economic effects of the lower exhaustibility of knowledge as an economic good with respect to standard goods. Attention has been focused on non-excludability, the first key characteristic of public goods. Yet its application to knowledge implies necessarily the identification and appreciation of the role, not only of its limited appropriability, but also of its limited exhaustibility.

As a matter of fact the limited exhaustibility of knowledge lies at the heart of its non rivalry in use, another—much better known—property. Non rivalry in use applies to public economic goods characterized by indivisibility of benefits: “A good is nonrival or indivisible when a unit of the good can be consumed by one individual without detracting, in the slightest, from the consumption opportunities still available to others from that same unit. Sunsets are nonrival or indivisible when views are unobstructed.” (Coornes and Sandler 1986: 6). The definition of non rivalry in use has been progressively stretched and applied to a variety of impure public goods including knowledge (Stiglitz 1999). Its application to knowledge has not appreciated an important implication: non rivalry in use of knowledge takes place not only because of its non-excludability, but also because of its limited exhaustibility. The possibility to sharing knowledge, and yet retaining the possibility to keep using it, is possible only because of its non-exhaustibility. It seems quite obvious that the use by an agent of a standard excludable economic good characterized by standard exhaustibility excludes the possibility that a second agent can keep using it at the very same conditions. The limited exhaustibility of knowledge and its non excludability, stemming from its limited appropriability, are intertwined since the very first steps of the economics of knowledge. It is necessary to disentangle their separate effects.

As a matter of fact, the comparative analysis of standard economic goods and knowledge as an economic good shows that the exhaustibility of knowledge is much lower than the exhaustibility of standard economic goods.

Standard economic goods are characterized by high levels of exhaustibility. Consumer goods, such as food or personal services are fully exhausted by their consumption. Durable consumer goods have lower levels of exhaustibility: yet their duration is limited. Intermediary goods are fully exhausted by their transformation into output. Capital goods have a longer duration. Economic obsolescence is usually faster then their physical exhaustion. The introduction of superior capital goods makes existing capital goods that are not yet exhausted by physical wear and tear, obsolete.

The exhaustibility of knowledge is limited. Consumption of knowledge as a final good does not imply its exhaustion. The use of knowledge as an intermediary input does not entail exhaustion. The same piece of knowledge can be used repeatedly as an intermediary input without any effect on its duration. Finally, the use of knowledge as a capital good does not entail any physical wear and tear. The duration of knowledge as a capital good may be exposed to economic, rather than physical obsolescence. The introduction of superior knowledge may reduce the economic life of existing knowledge.

The understanding of the multiple role of knowledge that acts twice as an input and once as an output unveils another limit to its exhaustibility.

Knowledge in fact is an essential input in the technology production function, i.e. the production of all kind of goods (Griliches 1979, 1984, 1986, 1992; Griliches and Pakes 1984) as well as the output of the knowledge generation as a dedicated activity (Jaffe 1986). The generation of knowledge as an output, moreover, is the result of the recombination of existing knowledge: knowledge enters the knowledge generation function as an indispensable input (Weitzman 1996). Even after that existing knowledge experiences economic obsolescence as a capital good used in the production of other goods, it remains an indispensable intermediary input in the generation of new knowledge.

The analysis of the multiple role of knowledge as: (1) an input in the technology production function; (2) an output of the knowledge generation function; (3) an input in the knowledge generation function enables to grasp the radical difference in terms of exhaustibility of knowledge as a capital good with respect to standard capital goods. The economic obsolescence of standard capital goods entails their economic exhaustion. This is not the case of knowledge. Its economic obsolescence may entail its exhaustion as an effective capital good in the technology production function, but not in the knowledge generation function, where it remains an indispensable intermediary input.

The limited exhaustibility of knowledge has important implications for economic analysis and policy. In the theory of growth, the limited exhaustibility of knowledge has important implications as it engenders the accumulation of a stock of knowledge. This in turn may lead to the possible reduction of the access and use cost of knowledge as an input. In the context of the induced technological change approach, the reduction of the cost of knowledge should exert a clear effect on the knowledge-intensive direction of technological change (Antonelli 2018). The limited exhaustibility of knowledge has important implications for policy analysis as it questions the Arrovian analysis of the limits of knowledge as an economic good.

3 The intertemporal derived demand of knowledge

The limited exhaustibility of knowledge has powerful effects on its derived demand. The analysis of the derived demand is a powerful tool that enables to identify the effects of the limited exhaustibility of knowledge compared to the standard exhaustibility of economic goods that enter a technology production function as capital (and intermediary) inputs (Antonelli 2017).

The formal analysis of the derived demand for technological knowledge enables to follow and yet stretch the application of the Arrovian approach from the analysis of knowledge as an output to the analysis of knowledge as an input. We can proceed with the same comparative approach confronting the outcomes of knowledge as a standard good with substantial exhaustibility to the outcomes of knowledge as a non-standard good characterized by limited exhaustibility.Footnote 1

The analysis of the derived demand of a capital good with an economic life that lasts more than a single unit of time requires to take into account the distribution of the yearly economic benefits distributed over the stretch of time along which the capital good remains into operation taking into account the erosion effects of its obsolescence. When the economic life of a capital good exceeds the single unit of time it is necessary to move from the instantaneous derived demand to the intertemporal derived demand.

The intertemporal position of the derived demand of any intermediary and capital good (K) is determined by the horizontal sum of the instantaneous derived demand schedules, that is the yearly schedules of its (PYP’K) the product of the price (PY) of the output (Y) and marginal product in physical quantities (P’K) taking into account the rates of obsolescence that reduce the portion of the capital good in use each year.

For the same token, the intertemporal derived demand of knowledge as an input in the technology production function is determined by the horizontal sum of the instantaneous derived demands measured at each point in time by its marginal product in value (PYP’T) that is the marginal product in physical quantities of knowledge (T) as an input in the technology production function—times the price of output Y, taking into account the rates of obsolescence that reduce the portion of the capital good in use each year (Antonelli 2017).

The rates of obsolescence play a major role to identify the position of the intertemporal derived demand as they have a strong effect on the time distribution of the sequence of marginal products of the portions of input that remain in the production process. At each point in time the position of the intertemporal derived demand is determined by the sum of the instantaneous schedules of derived demand over the stretch of time through which the knowledge input exerts its productive effects taking into account the non-exhausted portion still effective.

The starting point is the Cobb–Douglas specification of the knowledge production function:

where Y stands for the output, K for the capital stock, L for the labor input and T for the knowledge stock.

In the case of standard intermediary and capital goods the economic and physical obsolescence entails the yearly reduction of their marginal product in value (PYP’K). Assuming standard economic parameters, the (PYP’K) of the first year is 100%, the (PYP’K) of the second year is reduced to 80%, the (PYP’K) of the third year is reduced to 60% and so on until the capital good is fully exhausted.Footnote 2

According to the analysis conducted above it seems possible to claim that the exhaustion of knowledge in its dual role of capital good in the technology production function and intermediary good in the knowledge generation function takes place at slow rates. Much slower than any standard economic good.

In the case of knowledge the economic and physical obsolescence entails a far lower yearly reduction of its marginal product in value (PYP’T). Assuming a possible parameter, the (PYP’T) of the first year is 100%, the (PYP’T) of the second year is reduced to 95%, the (PYP’T) of the third year is reduced to 90% and so on until knowledge is actually exhausted.

Because the analysis implemented so far does not take into account the effects of the limited appropriability of knowledge that will be considered at a later stage, it seems clear that the position of the intertemporal derived demand of knowledge, calculated as the horizontal sum of the yearly schedules of the marginal products in value of the non-exhausted portions of knowledge, is far higher than the position of the intertemporal derived demand of any other capital good.

The intertemporal derived demand of standard capital goods assuming that the current period were t1 and the initial year t0 and taking into account depreciation/obsolescence (d), is:

Although the instantaneous derived demand of knowledge (where the depreciation/obsolescence rate is δ) equals the instantaneous derived demand of any other capital good:

The intertemportal derived demand for knowledge is larger than the intertemporal demand for capital when the effects of the duration of capital goods and knowledge over a stretch of time that is larger than the unit are taken into account. It is, in fact, clear that:

Equation (4) holds because the exhaustibility of knowledge is lower than the exhaustibility of standard capital goods and consequently larger portions of knowledge capital remain in service with respect to contemporary capital goods. As a consequence the intertemporal derived demand for knowledge lies far above the derived demand for any standard capital good:

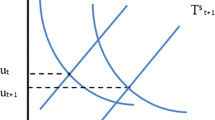

Figure 1 shows the implications. The higher position of the intertemporal derived demand for knowledge (D1) stemming from its limited exhaustibility contrasts the lower position of the intertemporal derived demand for standard economic goods (D2) stemming from their higher levels of exhaustibility that reduce the efficiency time window of a given capital good. The position of (D2) can be regarded as the benchmark. Out-of-equilibrium conditions take place when the position of the derived demand for knowledge does not coincide with the benchmark and lies either above or below it.

Assuming a standard supply curve (S) with a positive slope, it is clear that, not only the equilibrium demand for knowledge (QTA) is larger than the equilibrium demand for any standard economic good, (QTB) but also the price of knowledge (PTA) is larger than the benchmark equilibrium price of any standard capital good (PTB).

Because of the crucial role of the limited exhaustibility of knowledge -without taking into account the effects of its limited appropriability—the incentives to allocate resources to generate knowledge are not lower but actually larger than the incentives to allocate resources to standard economic goods. The analysis of the effects of the limited exhaustibility of knowledge suggests, in fact, that markets may oversupply knowledge rather than undersupply it. The Arrovian market failure would work the other way around: too much knowledge is generated and too little standard capital goods are demanded by the system. Too much investment in knowledge takes place and too little investments take place in standard tangible goods. Because of excess duration of its economic life there is an excess-supply of knowledge.

4 The limited exhaustibility and appropriability of knowledge

The Arrovian analysis of knowledge as an economic good concentrated its attention of the limited appropriability of knowledge. It is now time to bring it back into the frame. The limited appropriability entails the spillover of proprietary knowledge: “inventors” cannot retain the full stream of benefits stemming from the generation of new technological knowledge and the related introduction of innovations. Imitators can take advantage of the knowledge generated by inventors. Imitation enables the entry of new competitors and the generalized use of process innovations with the consequent downward shift of the supply curve and the fall of the price of products that have been produced by means of new knowledge (PY).Footnote 3

The uncontrolled leakage of knowledge and its spillover, however, arenot instantaneous. The large evidence provided by the literature confirms that imitation and absorption are not free but entail consistent resources and dedicated activities that need time to display their effects (Mansfield 1981, 1986). Spillovers are not instantaneous, but diachronic. As a consequence their effects are distributed aver time: the entry of new competitors exerts its effects through time. Innovators can fully appropriate the economic benefits of their innovation only in the first unit of time (year). In the second, fast imitators and incremental innovators -that rely on proprietary knowledge leaking from inventors—enter the market place and bring about a reduction of the prices. The price of the innovated products declines progressively:

The effects of the limited appropriability of knowledge on its derived demand consist in the reduction of the value of the marginal product of knowledge. The limited appropriability of knowledge entails a backward shift of the position of its derived demand. The fall of prices takes place at augmented rates in the third and following years. Now the position of the intertemporal derived demand for knowledge determined by the horizontal sum of the different time schedules of the instantaneous derived demands is affected by the progressive reduction of PY

The derived demand schedules D3, D4 and D5 of Fig. 1 exhibit the outcome. The position of the intertemporal derived demands of knowledge shifts according to the different assumptions about the rates of decline of the prices of the output (PY).

The amount of the actual backward shift is of course a matter of empirical evidence. It is clear that the position of the intertemporal derived demand for knowledge will coincide with the position of the demand for standard capital goods when the rate of economic and physical obsolescence of standard capital goods equals the rate of decline of the prices of innovated goods stemming from the limited appropriability of knowledge:

In Fig. 1 this is the case of the coincidence between equilibrium points B and E where B is found on D2 that represents the intertemporal derived demand of standard economic goods with standard exhaustion and E belongs to the intertemporal derived demand curve of knowledge with diachronic spillovers that engender a sequence of lower prices of the output Y. In this case the rate of depreciation of standard economic goods and the rate of decline of the price of the output Y coincide. This is the case where the limited exhaustibility of knowledge engender positive effects on the derived demand that are exactly compensated by the negative effects that stem from the uncontrolled leakage of proprietary knowledge that in turn causes the entry of new competitors and the limited appropriability of the knowledge generated by ‘innovators’. In this case the limited exhaustibility of knowledge acts as an effective countervailing property that can balance the negative effect of the limited appropriability of knowledge. The positive effects of the limited exhaustibility of knowledge balance the negative effects of its limited appropriability.

If the rates of decline of the price of innovated goods are lower than the rates of obsolescence, the market place will suffer from excess supply of knowledge. The position of the intertemporal demand for knowledge remains above the position of the intertemporal derived demand of standard economic goods:

In this case the market place is likely that produce too much knowledge at prices that are larger than it would take place if knowledge were a ‘perfect’ economic good. The market failure takes place but the effects are opposite to the Arrovian market failure.

In Fig. 1 this is the case of equilibrium point C that belongs to D3 that represents the intertemporal derived demand curve of knowledge with diachronic spillovers that engender a sequence of lower prices of the output Y that have negative effects on the position of the derived demand far lower than the effects of the standard exhaustibility of capital goods represented by the benchmark derived demand D2. This is the case of knowledge characterized by high levels of cumulativity that enables ‘inventors’ to exploit it through time and to use it in the recombinant generation of new knowledge so as to stretch the duration of monopolistic power and the height of barriers to entry and to mobility. In this case both the price and quantity of knowledge are far larger than it would take place if knowledge had standard economic characteristics. The prices of innovated goods decline at a rate that is far lower that the decline of the efficiency time window of standard economic goods. The limited exhaustibility of knowledge has ‘positive’ effects that overcompensate the ‘negative’ effects of its limited appropriability.

The well known Arrovian case of knowledge market failure will take place when and if the rates of decline of the prices of innovated goods, engendered by the diachronic effects of the limited appropriability of knowledge, yield negative effects than the positive ones stemming from the slow rates of exhaustion rates of obsolescence and as a consequence the position of the intertemporal derive demand for knowledge is lower that that of any standard capital good:

This is the case of equilibrium point F in Fig. 1. Point F belongs to D5 that represents the intertemporal derived demand curve of knowledge with diachronic spillovers that engender a sequence of lower prices of the output Y. In this case the reduction of the price of innovated goods has negative effects on the position of the derived demand far larger than the effects of the standard exhaustibility of capital goods represented by the benchmark intertemporal derived demand D2. This is the case of knowledge items that have low levels of natural appropriability and that consequently can be easily imitated and absorbed by free-raiders. In these special cases the market place is unable to allocate the correct amount of resources to the generation of knowledge that produces knowledge at costs that are below equilibrium levels.

The Arrovian market failure takes place—only—in this latter case. The system is unable to allocate the appropriate amount of resources to the generation of knowledge and its use in the introduction of innovations when the negative effects of its limited appropriability on the incentives to invest in R&D outweigh the positive effects of its limited exhaustibility. The Arrovian knowledge market failure is no longer a general case that applies in all circumstances: it is a possibility that takes place in circumstances that need to be specified and investigated.

The identification of the substantial heterogeneity of knowledge enables to use the analytical framework implemented so far as not only as a didactic device but an actual and effective tool able to discriminate across knowledge items. A large literature provides evidence on the heterogeneity of knowledge: Adams and Clemmons (2013) calibrates diffusion lags among fields and sectors for science, finding that while the mean lag is about 6 years in standard data, there is a clear evidence across fields. Knowledge is a bundle of heterogeneous items that are differentiated by varying levels of exhaustibility and appropriability.Footnote 4 Their different combinations enable to classify knowledge into different classes of “economic imperfections” and consequently different types of market failures:

-

1.

knowledge items with low exhaustibility and high appropriability lead to an inverse market failure, i.e. the excess supply of knowledge;

-

2.

knowledge items with high exhaustibility and low appropriability lead to the classic market failure characterized by undersupply;

-

3.

knowledge items for which high levels of exhaustibility compensate low levels of appropriability are not expected to engender any market failure.

5 Conclusions

The analysis of knowledge as an economic good is a fertile and promising field of investigation. Knowledge has several idiosyncratic properties that deserve all to be identified and explored in detail. Their implications and consequences are most important and need to be considered all together. The economic literature has paid much attention to a sub set of the broader bundle of knowledge idiosyncratic features. Attention has been attracted primarily if not exclusively by its limited appropriability, its non-rivalry in use, the sharp difference between generation and reproduction costs. The selection of these features has led to a substantial consensus about the limits of knowledge as an economic good and their consequences in terms of market failure.

The exploration of the full range of properties of knowledge as an economic good reveals other important features. Their assessment can complement the analyses based on the limited appropriability of knowledge alone. The identification of the limited exhaustibility as a key intrinsic property of knowledge enables to modify the standard frame according to which knowledge has many shortcomings and weaknesses as an economic good. Actually the ‘discovery’ of the limited exhaustibility of knowledge seems to uncover unexpected merits and strengths of knowledge as an economic good. Such unexpected merits and strengths yield positive effects in terms of dynamic increasing returns that are most likely to increasing -rather than decreasing—the incentives to the allocation of resources to its generation so as to engender extreme cases of augmented knowledge supply rather than undersupply.

These results call for the implementation of a new framework for knowledge policy aimed at: (1) increasing the additionality of R&D subsidies so as to foster the rates of accumulation of the stock of quasi-public knowledge and (2) limiting the exclusivity of intellectual property rights so as to fostering the dissemination of knowledge in the system and reducing its costs of access and use.

The systematic and generalized provision of exclusive intellectual property rights and automatic public subsidies to the generation of all kinds of knowledge, irrespective of their actual levels of exhaustibility and appropriability should be reconsidered. The heterogeneity of knowledge in terms of varying levels of exhaustibility and appropriability should be operationalized to design a differentiated set of knowledge policies.

The public support based on automatic subsidies to the generation of knowledge characterized by very low levels of appropriability and high exhaustibility seems appropriate because of the high risks of Arrovian market failure. The reduction of the cost of knowledge generation is necessary and the additionality requirements can be weaker. The public support to both the generation of knowledge characterized by low levels of exhaustibility and high levels of natural appropriability should be reconsidered. In this case the additionality requirements of public subsidies to R&D activities should be strong. Targeted subsidies should play a stronger role in the mix of public interventions. The selective rather than automatic support to the generation of knowledge characterized by very low levels of appropriability and high exhaustibility seems necessary in order to contrast pervasive crowding out effects.

The differentiation of intellectual property rights with the introduction of knowledge-specific patents with varying terms and levels of exclusivity should be implemented so as to take into account the intrinsic heterogeneity of knowledge in terms of levels of appropriability, with their twin positive and negative effects, and exhaustibility.

Notes

The comparison between knowledge as an economic good and standard economic goods explores here exclusively the effects of the limited exhaustibility of knowledge and does not—yet—integrate the effects of its limited appropriability. The integration of the effects of both the limited exhaustibility of knowledge and its limited appropriability will be implemented in Sect. 4.

The rates of tax depreciation provide a reliable clue about the actual obsolescence of tangible capital goods. Although they exhibit a relevant variance—the heights of 30–40% for petrochemical and digital capital goods, to 25% for machinery—they confirm that the average duration of the economic life of tangible capital goods rarely exceeds 4 years.

The analysis implemented in this Section considers only the ‘negative’ effects of the limited appropriability of knowledge on the price of innovated goods and hence on the revenue of innovators and consequently on the position of the derived demand for knowledge. It does not integrate the analysis with the appreciation of the ‘positive’ effects of the limited appropriability of knowledge in terms of the knowledge spillovers that help reducing the cost of innovators with the consequent downward shift of the supply of innovated goods and not only of the derived demand of knowledge (See Antonelli 2017).

Patent statistics provide important clues to gauge the levels of knowledge exhasutibility and appropriability: (1) the levels of knowledge exhaustibility can be approximayed by the rates of advance of knowledge as measured by the rates of patents applications of technological classes. The larger are the rates of increase of applications in a class and the faster can be thought to be the rates of obsolescence of the papternts that belong to that technological class; (2) the dates of backward citations provide additional information about the levels of knowledge exhaustibility. The longer the time span between backward citations and dates of application and the lower the exhaustibility; (3) the levels of knowledge appropriability can be approximated by the amount of current backward citations: the larger the number of current backward citations and the larger are expected to be the effort to inventing around.

References

Adams, J. D., & Clemmons, R. J. (2013). How rapidly does science leak out? A study of the diffusion of fundamental ideas. Journal of Human Capital, 7, 191–229.

Aghion, P., & Howitt, P. (1992). A model of growth. Through Creative Destruction, Econometrica, 60(2), 323–351.

Antonelli, C. (2017). Endogenous innovation. The economics of an emergent system property. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Antonelli, C. (2018). The evolutionary complexity of endogenous innovation. The engines of the creative response. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Antonelli, C., & Crespi, F. (2013). The “Matthew Effect” in R&D public subsidies: The case of Italy. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 80, 1523–1534.

Antonelli, C., Crespi, F., & Scellato, G. (2015). Productivity growth persistence: Firm strategies, size and system properties. Small Business Economics, 45, 129–147.

Arrow, K. J. (1962). Economic welfare and the allocation of resources for invention. In R. R. Nelson (Ed.), The rate and direction of inventive activity: Economic and social factors (pp. 609–625). Princeton: Princeton University Press for NBER.

Arthur, W. B. (2009). The nature of technology: What it is and how it evolves. New York: Free Press.

Cornes, R., & Sandler, T. (1986). The theory of externalities public goods and club goods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dosi, G. (1988). Sources, procedures, and microeconomic effects of innovation. Journal of Economic Literature, 26, 1120–1171.

Griliches, Z. (1979). Issues in assessing the contribution of research and development to productivity growth. Bell Journal of Economics, 10(1), 92–116.

Griliches, Z. (Ed.). (1984). R&D patents and productivity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press for NBER.

Griliches, Z. (1986). Productivity, R&D, and basic research at the firm level in the 1970s. American Economic Review, 77(1), 141–154.

Griliches, Z. (1992). The search for R&D spillovers. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 94(Supplement), 29–47.

Grossman, G. M., & Helpman, E. (1994). Endogenous innovation in the theory of growth. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 8(1), 23–44.

Jaffe, A. (1986). Technological opportunity and spillovers of R&D: Evidence from firms’ patents, profits, and market value. American Economic Review, 76(5), 984–1001.

Kogut, B., & Zander, U. (1992). Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities, and the replication of technology. Organization Science, 3, 383–397.

Mansfield, E. (1981). Composition of R and D expenditures: Relationship to size of firm, concentration, and innovative output. Review of Economics and Statistics, 63, 610–615.

Mansfield, E. (1986). Patents and innovation: An empirical study. Management Science, 32, 173–181.

Pakes, A., & Griliches, Z. (1984). Patents and R&D at the firm level: A first look. In Z. Griliches (Ed.), R&D patents and productivity (pp. 55–72). Chicago: University of Chicago Press for NBER.

Penrose, E. T. (1959). The theory of the growth of firm. London: Basil, Blackwell.

Romer, P. M. (1990). Endogenous technological change. Journal of Political Economy, 98, S71–S102.

Stiglitz, J. (1999). Knowledge as a global public good. In I. Kaul, I. Grunberg, & M. Stern (Eds.), Global public goods: Inernational cooperation in the 21st century. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Teece, D. J. (2000). Managing intellectual capital. Organizational strategic and policy dimensions. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Weitzman, M. L. (1996). Hybridizing growth theory. American Economic Review, 86(2), 207–212.

Acknowledgement

The support of the research funds of the Dipartimento di economia e statistica Cognetti de Martiis of the University of Torino and of the Collegio Carlo Alberto is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Antonelli, C. Knowledge as an economic good: Exhaustibility versus appropriability?. J Technol Transf 44, 647–658 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-018-9665-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-018-9665-5

Keywords

- Knowledge exhaustibility

- Appropriability trade-off

- Intertemporal knowledge derived demand

- Knowledge market failures