Abstract

This study aimed to explore the spiritual pain concept in the Iranian-Islamic context using a hybrid research model during 2020–2021. During the first phase, international and Iranian-Islamic literature was systematically searched and reviewed. During the second phase, the researchers referred to oncology wards, palliative care centers, and intensive care units and conducted unstructured interviews with 19 dying patients. In the third phase, attributes, and final analysis of spiritual pain was extracted from the first phase, and following the second phase, the definition of spiritual pain was finalized. The results showed that spiritual pain is a type of unique transcendental pain in the context of a continuum, rooted in human nature. At the one end of the continuum, there is the pain of deprivation from worldly pleasures (oneself, the family, and others). At the other end, there is the pain of breaking away from and striving to return to one’s origin (God). Exploring spiritual pain in the Iranian-Islamic context can help develop tools and clinical guidelines and plan for the presence of specialists at the bedside to relieve this pain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Being diagnosed with chronic or life-threatening illnesses can lead to a patient’s spiritual distress. This turbulence may be short for some patients and long for others, according to the efforts made by individuals to understand their perceptual reality and what gives their life value and meaning. This process may lead to growth and transformation for some people and to distress, despair, and ultimately, spiritual pain for others (George & Park, 2017). Spiritual pain has been defined as a deep non-physical pain in the soul (Delgado-Guay et al., 2011; Mako et al., 2006). Spiritual pain is also considered as part of total pain (Heyse-Moore, 1996). In the study of Mako et al., three main components were identified for spiritual pain, corresponding to the intrapersonal (despair and isolation), interpersonal (isolation), and transpersonal (frustration and anxiety) aspects (Mako et al., 2006; Schultz et al., 2017). In a study by Delgado et al., 96% of patients with cancer reported spiritual pain (Delgado-Guay et al., 2011). In addition, 44–61% of outpatients with cancer were reported to suffer from physical symptoms, psychological distress, and financial problems, leading to a reduction in quality of life in those with advanced cancer (Pérez-Cruz et al., 2019). The patient’s suffering from pain can also cause the suffering of his/her caregivers as well (Delgado-Guay et al., 2011).

Millspaugh considers spiritual pain the same as bodily pain and suffering and argues that this type of pain results from a complex interaction between various factors, including awareness of death, loss of relationships, self-destruction, and loss of purpose, control, and life-affirming, a phenomenon that is beyond the purpose and a sense of internal control (Millspaugh, 2005). Finally, Murata defines spiritual pain as the pain caused because of the destruction or extermination of one’s existence and meaning. Spiritual pain originates from the feeling of losing the basic components of one’s meaning of existence: the loss of relationships, the loss of independence, the loss of the future, and heading toward death (Ichihara et al., 2019; Murata, 2003).

Physiological pain and spiritual pain differ from each other in the views of materialistic and secular versus monotheistic insights. In religious, philosophical, and mystical teachings, some diseases and pains are considered positive and good, believing that pain and illness are actually pleasant entities that bring the individual closer to God, the divine and eternal source of blessings (Cheraghi et al., 2016). From an Islamic perspective, a person’s suffering from pain reminds him/ her of God. Considering pain and suffering as Godly trial and a means of purifying and polishing human soul, makes them meaningful and tolerable for the believers. (Mahdavi Azadboni & Alizadeh, 2017). It is noteworthy that not everyone has the talent and capacity for spiritual pain. Rather, spiritual pain requires appropriate background and competencies to occur. In religious texts, calamity has often befallen prophets because the suffering would bestow them with a higher spirit.

Regarding the aforementioned, healthcare providers need to pay more attention to spiritual conflicts/ spiritual suffering/ spiritual pain and provide the interventions required. A literature review discloses that further studies are still needed to divulge the concept of spiritual pain and its various dimensions. Moreover, this concept is influenced by the cultural context of every country. At the beginning of this study, a general concept of spiritual pain applicable to all members of society was considered. However, after the primary literature review and before starting the main body of the study, it was found that in Western culture, spiritual pain is only implicated in the last stages of life when the individual is dissociated from this world and enters another world. Accordingly, considering that one of the three main steps of the study (literature review) was the reviewing of comprehensive international and Islamic texts, end-of-life patients in Islamic and secular nations were considered the target population. Besides, there was no study on the concept of spiritual pain in end-of-life patients in the Iranian-Islamic context.

Objective

Considering the specific qualities and attributes of spiritual pain in Iranian-Islamic framework and its differences with other cultural and religious backgrounds, the aim of this study was to explore spiritual pain in end-of-life patients in the Iranian-Islamic context using a hybrid model.

Methods

This study was conducted with a hybrid approach consisting of three phase: theoretical, field-work, and final analysis.

The Theoretical phase

Searching the relevant literature was conducted according to the guide provided by the University of York. This guide includes selecting the review question, developing a search strategy, determining inclusion/ exclusion criteria, source appraisal, data extraction, and data analysis (Tacconelli, 2010).

Web of Sciences, PubMed, and Scopus were searched for English articles and SID and Magiran for Persian articles. Keywords searched included total pain, mystical pain, human pain, religious pain, love pain, holy pain, inner pain, religious anguish, spiritual pain, and inner pain without a time limit from 2000 to 2021.

Inclusion criteria for studies were publication in either Persian or English, being relevant to the definitions, features, facilitators, and deterrents of spiritual pain, and being peer-reviewed. Also, books on religion and Islamic-Iranian texts were included. Texts in other languages and letters to editors were excluded.

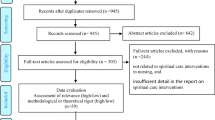

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programmed checklist for qualitative studies (CASP) and Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) were used to evaluate the quality of qualitative and quantitative studies, respectively. Figure 1 shows the process of appraisal and selection of studies in the theoretical phase. In the first step, duplicate articles were removed using Endnote software. In the next step, the abstracts were reviewed, and finally, the fulltext articles meeting the inclusion criteria were assessed using the relevant tools. A total of 50 English articles were included and analyzed. Out of 23 articles analyzed, most of them had used interviews and anecdotal descriptions or reported the cases speaking out about spiritual pain; No Persian articles were found, but there were two hadiths from Imam Sadegh (AS), and six hadiths from the Prophet Mohammad (PBUH). Also, parts of Sahifa Sajjadieh, the famous hadith attributed to Hazrat Zainab (AS) on the day of Ashura, who said despite the great calamity of losing all his relatives in an unequal battle: I saw nothing but beauty, the description of pain attributed to the prophet David (Hazrat Davood) and prophet Moses (Hazrat Musa), and some poems by Attar and Mowlana (Iranian poets) were also analyzed.

The texts of the articles and books extracted were analyzed using the conventional content analysis approach according to the steps proposed by Graneheim & Lundman. The text were thoroughly read word-by-word, line-by-line, and paragraph-by-paragraph several times to attain a general understanding. Then, parts of the texts were extracted, and the meaning units and primary codes were excerpted. The codes were read several times and categorized based on their similarities and relevance to the concept. Then, by segregating independent codes and merging similar ones together, classification was accomplished. The second-level coding was then performed. In the next step, the categories were compared with each other, and those sharing similar characteristics were combined to form a broader category. Attempts were made to reach the highest interclass homogeneity and the highest intra-class heterogeneity. Eventually, the categories were merged to form themes. In this phase, 500 primary codes emerged that lead to the formation of eight categories and 16 subcategories. The literature search also continued during the field-study phase.

The Field-work Phase

In this phase, unstructured face-to-face interviews were conducted with 19 end-of-life patients from November 2020 to November 2021. The interview began with warm-up questions and was followed by questioning the definition of spiritual pain. The participants were allowed to talk about experiencing this pain, which is different from physical pain.

Participants were included in the study in a purposeful sampling, and sampling was continued until reaching data saturation. Maximum variation in terms of sex, age, marital status, level of education, and type of disease was considered in the selection of participants. The interviews were conducted in Cancer Intensive Care Units and Palliative Care Centers, and the duration of the interview was determined based on the participant’s interest, lasting mainly between 30 and 45 min. However, due to the patient’s clinical condition, the researcher had to cease the interview several times so that the patient could rest. In two cases, the interview was postponed to subsequent days. The interviews were recorded by a digital device, then transcribed verbatim, reviewed, coded, and immediately analyzed. Data analysis was performed simultaneously and continuously, along with data collection. The participants’ sentences, as well as indicative codes (i.e., researchers’ excerpts from interviews), were used for extracting the initial codes. The codes were read several times, then reread and categorized based on their similarities and relevance to the subject unit. Then by segregating independent codes, repeatedly reviewing them, and merging similar codes, classification was performed.

In the next step, the categories were compared with each other, and those with similar characteristics were combined to form a broader category. The primary codes emerging from data analysis underwent constant comparison until the last stages of drafting the manuscript. During this process, the codes were reduced until finally, categories and subcategories were formed. In this phase, 301 primary codes emerged, leading to the formation of four categories, and 11 subcategories. For evaluating the data’s rigor, Lincoln and Cuba criteria (credibility, dependability, transferability, and confirmability) were used.

The Final Phase

In the final phase, the codes and categories extracted during the field-work phase were compared with those obtained from the literature review (theoretical phase) to create the final definition of spiritual pain.

Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Qom University of Medical Sciences, Qom, Iran (IR.MUQ.REC.1399.262). Data confidentiality was observed in this study, and informed consent was obtained from the patients. The participants were also asked for permission to record interviews.

Results

The Theoretical phase

The Definition and Explanation of the Features and Concept of Spiritual Pain

-

1.

Based on the review of the literature and Islamic-Iranian textbooks, the features of the spiritual pain concept were presented in four dimensions:

-

2.

The continuum of spiritual pain

-

3.

Hidden nature of spiritual pain 3—The uniqueness of the nature of spiritual pain

-

4.

The transcendent nature of spiritual pain (Table 1)

The Facilitators and Deterrents of Relief from Spiritual Pain during End-of-life Care

The factors either facilitating or hindering relief from spiritual pain during end-of-life care have been addressed in studies, either implicitly or explicitly. These factors can be placed into two general categories: human factors and organizational factors.

Human Factors Involved in Relieving Spiritual Pain during End-of-life Care

According to the literature, one of the most important reasons contributing to the spiritual pain remaining unrelieved was either the unwillingness or inability of the treatment team to identify this type of pain. However, another factor playing a role in the lack of relief may root in the nature of spiritual pain. All theology is completely personal. Spiritual pain is not a concept that you can think about it; instead, everyone knows about it, or it is a universally accepted concept. In fact, everybody may experience some degree of spiritual pain (Pérez-Cruz et al., 2019).

Nevertheless, this concept is not well-known. In some cases, this pain may even be considered mental or emotional pain. In the case of palliative care, spiritual pain and total pain may be used interchangeably. Despite this, spiritual pain is experienced by most people, especially during suffering, diseases, and the later stages of life, when this pain is clearer.

In addition, factors such as time insufficiency, treatment team members’ belief that relieving spiritual pain is not part of their duties, failure to identify the patient’s preferences, religion, and culture, lack of a trust-based relationship between the patient and treatment team, lack of relevant education about this pain, confusion about who is responsible for relieving this type of pain, and the uniqueness of this pain are among the most important items leading to this type of pain remaining undiagnosed (Elsdon, 1995; Ichihara et al., 2019).

The desire of the family, the psychological reactions of the patient and the family, and the life-threatening nature of the disease can be either facilitators or inhibitors of spiritual pain relief (Ichihara et al., 2019; Tamura et al., 2006).

Organizational Factors Involved in Relieving Spiritual Pain in End-of-life Care

Organizational factors can be divided into two categories: organizational factors in eastern and western cultures:

The western biomedical model emphasizes more on the biological aspects of pain, while other dimensions of pain have not been adequately studied. In fact, the philosophy of Cartesian dualism is still the prevailing theory. According to the bio-psychosocial model, however, pain possesses additional aspects other than biological dimension, so all of these aspects must be considered. In fact, the identification, evaluation, and alleviation of total pain are among the most important goals that should be considered. The identification, evaluation, and management of pain in end-of-life patients are of special importance in explaining the philosophy behind the existence of palliative care specialists. They must identify and take measures to eliminate the total pain, especially the spiritual pain, in patients (de Araújo Elias et al., 2006).

The lack of adequate knowledge and skills by the treatment team, the lack of professional competence, organizational rules and atmosphere, hospital regulations and policies, and the shortage of financial and human resources are among the most important deterrent factors for relieving spiritual pain (Brunjes, 2010; Musi, 2003).

In Eastern culture, failure to identify and explain spiritual pain by specialists, lack of attention to the conceptualization of this pain, lack of education on this pain in the curricula of medicine, psychology, and even religious studies are the most important reasons for not paying attention to relieving this pain (Fasihizadeh & Nasiriani, 2020; Musa, 2017).

The lack of ongoing education and counseling programs is an important factor that can affect the ability of the treatment team and other interdisciplinary team members to alleviate spiritual pain. There is a need for considering special training and hiring trained personnel to properly provide care for relieving spiritual pain (Ichihara et al., 2019).

The Consequences of the Spiritual Pain Concept in End-of-life Care; the Theoretical Phase

Overall, considering the codes extracted after the literature review, the outcomes of the concept were classified into two categories:

Providing Peace and Comfort to the Patient and Family

The Patient’s Peace of Mind (reducing the patient’s stress and conflicts, alleviation of biological pain, promoting the patient’s sense of security) and The Family’s Peace of Mind (Diminishing tensions and conflicts within the family, alleviating the family’s feeling of guilt).

Ideal Care

Empowering the Treatment Team in Providing Patient Care (strengthening the confidence of the treatment team and promoting the care services provided to the patient), Boosting Satisfaction (patient satisfaction, family satisfaction and satisfaction of the treatment team), and Improving the quality of care (accelerating the process of the patient’s physical or spiritual recovery and avoiding the wasting of resources and human resources).

Spiritual Pain Definition

Based on the findings of the literature review (Islamic-Iranian and secular texts) and analysis of the spiritual pain concept based on the Iranian-Islamic context using a hybrid method, the primary definition of the spiritual pain can be presented as follows:

“Transcendental pain is a continuum with unique features, rooted in human nature. The continuum ranges from being deprived of worldly pleasures to segregation from one’s origin and returning to one’s nature. The pain presents both explicitly and implicitly and is highly contagious.” The provision of care for such pain is influenced by various human and organizational factors such as the ability to differentiate this type of pain from other psychological problems and pains, the willingness of the family to receive such care, the psychological-cognitive reactions of the patient and the family, the life-threatening nature of the disease, the level of knowledge and skills of the treatment team, lack of professional competence, organizational rules and atmosphere, hospital regulations and policies, and shortage of financial and human resources. When spiritual pain is recognized, it can be properly managed and treated leading to outcomes such as peace and comfort, well-being, and ideal care to the patient and the family.

The Field-work Phase

The findings of this phase come from interviews with 19 patients at the end-of-life stage. The mean age of the participants was 44.90 (± 12.85) years. Other demographic features have been provided in Table 2.

The Features of the Concept of Spiritual Pain in End-of-life Care Based on the Findings of the Field-study Phase

The main attributes of the concept of spiritual pain according to the findings of this stage included dual-influence, captivity in the vortex of time and self-involvement, and painless pain. In the view of the participants, spiritual pain brought them a dual identity, meaning that although they were afraid of this pain, they were also willing to divulge the origin and nature of this pain, believing that this pain would bring them infinite perfection and an understanding of the reality of their existence. Meanwhile, they could not describe it to others, and if they did, no one could understand another person’s pain. This pain is on a continuum. On the one hand, there is a desire to reach the divine God, and on the other hand, there is concern about one’s children or situation. In fact, confusion and uniqueness is a notable characteristic of this pain. In order to better understand the conceptual features of this pain, the researcher expressed what the participants had stated in the form of a main theme and sub-themes (Table 3).

The Factors Facilitating or Hindering the Alleviation of Spiritual Pain in End-of-Life Care; the Findings of the Field-study Phase

According to the findings of the field-work phase, the factors facilitating or hindering the alleviation of spiritual pain in end-of-life care can be defined as follows: Unlike the findings of the literature review, the patients were found to consider human and organizational factors the same, believing that everyone was trying to help alleviate this pain despite the fact that they were never able to perceive the meaning of this pain. The lack of identification of this pain by the family and the medical team, as well as the patient’s inability to describe the pain, would render its management problematic. In fact, the lack of sufficient knowledge and the lack of similar terminology between the patient and the treatment team contribute to spiritual pain’s nature remaining unknown. Nevertheless, all members of the treatment team, as well as religious counselors, clerics, and psychologists, try to alleviate this pain. Of course, anyone can help ease this pain based on his/ her own understanding of its nature. Due to the lack of sufficient knowledge and the uniqueness of this pain, there is still insufficient comprehension of this concept. Meanwhile, there is no cure for this pain.

In this regard, a 39-year-old woman with a history of breast cancer with metastasis to the lungs and liver stated:

Some things are really indescribable; you cannot explain it at all because others do not understand what you are saying. They should be in your place to understand it.

The Consequences of the Spiritual Pain Concept in End-of-life Care; the Findings of the Field-study Phase

Based on interviews with the participants of this study, the outcomes of recognizing the spiritual pain concept during end-of-life care included peace and comfort for the patient and the family and the provision of ideal care to the patient.

Peace and Comfort for the Patient and the Family

-

The patient’s peace of mind (reduction of the patient’s distress and conflicts, reduction of the patient’s biological pain, boosting the patient’s sense of security)

-

The family’s peace of mind (reduction in the family’s tensions and disputes, reduction of the family’s feeling of guilt)

Ideal Care

-

Empowering the treatment team in patient care (boosting the treatment team’s confidence and improving the quality of healthcare provided to the patient)

-

Boosting satisfaction (patient satisfaction, family satisfaction and satisfaction of the treatment team)

The participants of this study stated that when their pain was identified, and few steps were taken to relieve their pain, although unsuccessful, this would lead their family to feel less guilty and find peace to some extent. By comprehending this sense of relief and peace in the family, the patient would also be able to achieve an inner positive feeling and become much calmer. In fact, a type of therapy for spiritual pain is the peace and comfort felt by the family. As soon as the patient realizes this peace, she/ he achieves calmness, and spiritual pain subsides, at least in part. The peace of the family also results from the patient’s calmness. When the patient’s family feel the patient is relieved, they also feel comfortable and less guilty. Through the alleviation of this pain, the treatment team’s members feel useful, encouraging them to seek more success in care provision. In this way, all the treatment team, the patient, and the patient’s family members become satisfied with the situation.

In this regard, participant No. 7 noted:

One of my worries at death is what would happen to my wife and children? I become anxious when I think about it. But when Mr. ………. comes and speaks with me, reminding me that God is protecting everyone, I become calm, and when my wife comes to visit me, I comfort her.

Comparison of Facilitators and Deterrents of Spiritual Pain Alleviation during End-of-life Care between the Theoretical and Field- work Phases

Regarding the facilitators and deterrents of spiritual pain alleviation during end-of-life care provision, these factors were classified as human and organizational items in the theoretical phase. In terms of human factors, facilitators included the desire of the patient and the family, the desire of the treatment team, the professional competence of the treatment team, personal characteristics, positive attitudes of medical team members, and interdisciplinary cooperation. On the other hand, human deterrents included the negative psychological reactions of the patient and family, the life-threatening nature of the disease, insufficient knowledge and skills of the treatment team, and the negative impacts of the personal preferences and beliefs of treatment team members. During the field-study phase, however, there was no segregation between human and organizational factors. The positive attitudes of medical staff and interdisciplinary cooperation between clergies, psychiatrists, and the members of the treatment team were the same in both phases. However, there was no mention of the treatment team’s professional competence in the field-study phase, while it appeared in the theoretical phase and during the literature review. Actually, this item often emerged as a deterrent factor in the form of professional incompetence, lack of knowledge and skills, and personal beliefs of treatment team members. During the field study, the latter (i.e., personal beliefs of treatment team members) was identified as a facilitator, which may be attributable to eastern cultures and the closeness of the patient’s personal beliefs to those of treatment team members, allowing medical staff to better understand the patient’s pain and declarations.

Comparison of the Consequences of Spiritual Pain Concept between the Theoretical and Field-work Phases during End-of-life Care Provision

During the field-work phase, the consequences of the spiritual pain concept appeared at the end-of-life stage included the main themes of providing peace to the patient and family (with the sub-themes of psychological peace, reduction in distress and conflicts, reduction in biological pain, boosting the sense of security and mental peace, reduction of distress and conflict in the family, and reduction in the family’s feeling of guilt) and ideal care (with the sub-themes of patient satisfaction, family satisfaction, and treatment team satisfaction). These themes were the same as those that emerged in the theoretical phase of the study. However, it is noteworthy that some sub-themes, including the improvement of the quality of healthcare services by accelerating physical and spiritual recovery of the patient, preventing the waste of resources and human resources, and improving treatments by acknowledging the situation, appeared only in the theoretical phase, but not in field-study phase. This observation may be related to the fact that during the field study (i.e., corresponding to the end-of-life stage), physical or spiritual recovery is far from the sight of the patient, who is in his/ her last days of life. Besides, the patient has no consideration for the loss of resources and human resources during this stage. Nonetheless, the control of the pain and physiological symptoms of the patient will indirectly prevent the waste of resources and human resources.

Final Analytic Phase

By combining the observations of the theoretical and field-work phases, the definition of spiritual pain was extracted as follows.

“Spiritual pain is a type of unique transcendental pain in the context of a continuum, rooted in human nature. At the one end of the continuum, there is the pain of deprivation from worldly pleasures (oneself, the family, and others). On the other end, there is the pain of breaking away from and striving to return to one’s origin (God). This pain is highly contagious and may present either overtly or covertly.” Spiritual pain is influenced by various human and organizational factors, including the inability to differentiate this pain from other psychological disorders and pains, the family’s wishes and desires, the patient’s and family’s psychological reactions, the life-threatening nature of the disease, insufficient knowledge and skills of the treatment team, lack of professional competence, organizational rules and atmosphere, hospital regulations and policies, and inadequate financial and human resources. If spiritual pain is recognized, it can be appropriately managed and treated, leading to positive consequences for the patient and his/ her family, such as peace, comfort, and provision of optimal care.

Discussion

Many believe that the main root of distress and turmoil of patients during the end-of-life stage is the experience of a type of pain that others cannot comprehend, nor can they describe it themselves. This has been termed as spiritual pain (Sulmasy, 2006). Mako et al. define spiritual pain as a kind of depression and anxiety caused by death and believe that this pain is actually rooted in anxiety of the unknown (Mako et al., 2006). This definition of spiritual pain is inconsistent with that appeared in the present study. In fact, based on the definition presented in the current study, this pain is not considered equal to anxiety and depression.

Mc Garth analyzed 12 open interviews with patients suffering from hematologic malignancies about spiritual pain and concluded that “spiritual pain results from the disruption of one’s connection with the body, soul, and other people and is an individual-dependent mental phenomenon, during which the individual sees a modified life and becomes aimless” (McGrath, 2002). Parts of this definition are in agreement with our findings; however, it considers the goal of life as influenced by this pain, while it was not the case in our study (i.e., no disruption of the goal of life, but purposeful returning of the person toward his/ her origin). Murata argues that spiritual pain is due to the extermination of one’s existence/ meaning and describes the final stages of life as the life’s losing its meaning and value, the loss of identity, the blurring of the future, disconnection from others, and loss of autonomy (Murata, 2003). This notion is consistent with some of the features that emerged in the definition of spiritual pain according to the present study. In both these definitions, spiritual pain has been described as losing the connection with others. Spiritual pain is not a new concept; rather it dates back to the beginning of human creation. This pain is a part of the total pain that patients experience at the end stages of their lives. Spiritual pain is linked with the person’s beliefs, and following the changing of the meaning of the person’s life, he/ she endures duality, leading to anxiety. Although there is no cure for this pain, it can be temporarily alleviated by actions such as listening to holy voices, visualizing the after-life world, praying, and touching holy objects. Assigning a religious representative at the end-of-life can be a great help in relieving this pain (Heyse-Moore, 1996).

Study Limitations

During the literature review, the full texts of some articles were not accessible despite numerous correspondence with the corresponding authors or the editors of the relevant journals. Also, sampling during the field study was performed amid the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, causing delays in the sampling process. Besides, some families refused our presence at the bedside of their patients in order to maintain social distance. Because the patients were at the end stages of their lives, it was not possible to conduct long interviews, and some patients were even unable to speak for 45–60 min. So, the researcher had to conduct multiple short interviews, but unfortunately, during the interval between the interviews, death embraced some patients, causing emotional pain for the researcher and disrupting the interview process.

Conclusions

Using the concept analysis method with a hybrid approach and by combining the data obtained from the literature review and the interviews performed during the field study, this study presents a new perspective regarding the concept of spiritual pain during the end-of-life stage. According to the findings of this study, spiritual pain is defined as “A type of unique transcendental pain in the context of a continuum, rooted in human nature. At the one end of the continuum, there is the pain of deprivation from worldly pleasures (oneself, the family, and others). On the other end, there is the pain of breaking away from and striving to return to one’s origin (God). This pain is highly contagious and may present either overtly or covertly.” Identifying this pain can be helpful in providing better care services and even developing tools for the quantitative assessment of this pain. On the other hand, the patients participating in this study believed that neither the members of the treatment team nor their family members were able to identify this pain, so they were incapable of curing it. This notion demonstrates the importance of the efforts to identify and alleviates this type of pain using the help of interdisciplinary experts. It seems that health professionals and policymakers should consider developing plans for the organized presence of spiritual pain specialists at the bedside of dying patients. According to the participants of this study, the alleviation of spiritual pain would subside biological pain and balance the patient’s hemodynamics, assisting in the provision of ideal care.

References

Brunjes, G. B. (2010). Practical approaches to spiritual pain. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 11, 37–39. http://journal.waocp.org/article_25166.html

Cheraghi, M. A., Bahramnezhad, F., Mehrdad, N., & Zendehdel, K. (2016). View of main religions of the world on; don’t attempt resuscitation order (DNR). International Journal of Medical Reviews, 3(1), 401–405. http://www.ijmedrev.com/article_63020_9c7c309bbe5fbf3278fcea7dd18fb7ef.pdf

de Araújo Elias, A. C., Giglio, J. S., de Mattos Pimenta, C. A., & El-Dash, L. G. (2006). Therapeutical intervention, relaxation, mental images, and spirituality (RIME) for spiritual pain in terminal patients. A Training Program. The Scientific World Journal, 6, 2158–2169. https://doi.org/10.1100/tsw.2006.345

Delgado-Guay, M. O., Hui, D., Parsons, H. A., Govan, K., De la Cruz, M., Thorney, S., & Bruera, E. (2011). Spirituality, religiosity, and spiritual pain in advanced cancer patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 41(6), 986–994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.09.017

Elsdon, R. (1995). Spiritual pain in dying people: The nurse’s role. Professional Nurse (London, England), 10(10), 641–643. PMID: 7630907. https://europepmc.org/article/med/7630907

Fasihizadeh, H., & Nasiriani, K. (2020). Effect of spiritual care on chest tube removal anxiety and pain in heart surgery in Muslim patients (Shia and Sunni). Journal of Pastoral Care Counseling, 74(4), 234–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/1542305020948189

George, L. S., & Park, C. L. (2017). Does spirituality confer meaning in life among heart failure patients and cancer survivors? Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 9(1), 131. https://doi.org/10.1037/rel0000103

Heyse-Moore, L. H. (1996). On spiritual pain in the dying. Mortality, 1(3), 297–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576279609696250

Ichihara, K., Ouchi, S., Okayama, S., Kinoshita, F., Miyashita, M., Morita, T., & Tamura, K. (2019). Effectiveness of spiritual care using spiritual pain assessment sheet for advanced cancer patients: A pilot non-randomized controlled trial. Palliative Supportive Care, 17(1), 46–53. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951518000901

Mahdavi Azadboni, R., & Alizadeh, S. M. (2017). Spiritual role of pain and suffer from Holy Quran and narrations view point. Quarterly Sabzevaran Fadak, 7(28), 71–91.

Mako, C., Galek, K., & Poppito, S. R. (2006). Spiritual pain among patients with advanced cancer in palliative care. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 9(5), 1106–1113. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1106

McGrath, P. (2002). Creating a language for’spiritual pain’through research: A beginning. Supportive Care in Cancer, 10(8), 637–646. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-002-0360-5

Millspaugh, C. D. (2005). Assessment and response to spiritual pain: Part II. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 8(5), 919–923. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2005.8.1110

Murata, H. (2003). Spiritual pain and its care in patients with terminal cancer: Construction of a conceptual framework by philosophical approach. Palliative & Supportive Care, 1(1), 15–21. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951503030086

Musa, A. S. (2017). Spiritual care intervention and spiritual well-being: Jordanian Muslim nurses’ perspectives. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 35(1), 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898010116644388

Musi, M. (2003). Creating a language for" spiritual pain": Why not to speak and think in terms of" spiritual suffering"? Supportive Care in Cancer, 11(6), 378–379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-003-0459-3

Pérez-Cruz, P. E., Langer, P., Carrasco, C., Bonati, P., Batic, B., Tupper Satt, L., & Gonzalez Otaiza, M. (2019). Spiritual pain is associated with decreased quality of life in advanced cancer patients in palliative care: An exploratory study. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 22(6), 663–669. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2018.0340

Schultz, M., Meged-Book, T., Mashiach, T., & Bar-Sela, G. (2017). Distinguishing between spiritual distress, general distress, spiritual well-being, and spiritual pain among cancer patients during oncology treatment. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 54(1), 66–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.03.018

Sulmasy, D. P. (2006). Spiritual issues in the care of dying patients:… it’s okay between me and God. JAMA, 296(11), 1385–1392. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.296.11.1385

Tacconelli, E. (2010). Systematic reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in healthcare. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 10(4), 226. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70065-7

Tamura, K., Kikui, K., & Watanabe, M. (2006). Caring for the spiritual pain of patients with advanced cancer: A phenomenological approach to the lived experience. Palliative Supportive Care, 4(2), 189–196. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951506060251

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted by Qom University of Medical Sciences, Qom, Iran

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Qom University of Medical Sciences, Qom, Iran (IR.MUQ.REC.1399.262). All Interviews performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Data confidentiality was observed in this study, and informed consent was obtained from the patients. The participants were also asked for permission to record interviews.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Yoosefee, S., Cheraghi, M.A., Asadi, Z. et al. A Concept Analysis of Spiritual Pain at the End-of-Life in the Iranian-Islamic Context: A Qualitative Hybrid Model. J Relig Health 62, 1933–1949 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-022-01654-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-022-01654-x