Abstract

Over the past decade, US adolescents’ depressive symptoms have increased, and changing religious beliefs and service attendance may be contributing factors. We examined the contribution of religious factors to depressive symptoms among 417,540 US adolescents (grades: 8, 10, 12), years:1991–2019, in survey-weighted logistic regressions. Among adolescents who felt religion was personally important, those who never attended services had 2.23 times higher odds of reporting depressive symptoms compared to peers attending weekly. Among adolescents who did not feel that religion was important, the pattern was reversed. Among adolescents, concordance between importance of religion and religious service attendance may lower risk of depressive symptoms. Overall, we estimate that depressive symptom trends would be 28.2% lower if religious factors had remained at 1991 levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Depression (Lu, 2019; Mojtabai et al., 2016) and depressive symptoms (Keyes et al., 2019) have been increasing among US adolescents since approximately 2011. In the USA, the 12-month prevalence of depressive episodes in adolescents increased from 8.3% in 2011 to 12.9% in 2016 (Lu, 2019). The reasons underlying this increase remain speculative and hypothesis-driven, with particular interest in the role of established risk factors for depressive symptoms that have undergone parallel changes.

One such factor is the salience of religion, as both religious service attendance and personal importance of religion have been declining among US adolescents (Twenge et al., 2015). The strength and magnitude of the association between religious involvement and depression are heterogeneous across the existing literature (Bonelli & Koenig, 2013; Braam & Koenig, 2019; Cotton et al., 2006). A recent examination of longitudinal studies concluded that among a wide array of religious factors, only participation in public religious activities and importance of religion were significantly tied to subsequent mental health, but the effect was small (Garssen et al., 2021). Braam et al. (2019) assessed 152 prospective studies, 27 of which focused on adolescents, and reported that, overall, 41% of the prospective studies on religious involvement and depression among adolescents exhibited a protective association. The relationship between religious involvement and depression among adolescents is inconsistent (Braam & Koenig, 2019; Cotton et al., 2006; Fruehwirth et al., 2019), and younger samples are less likely than older samples to report a protective effect of religious involvement on mental health (Braam & Koenig, 2019).

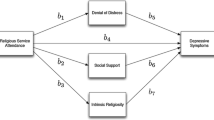

Religious involvement can reduce depressive symptoms as a coping mechanism for emotionally difficult life events, instilling messages of meaning and hope, and by providing a potentially supportive local community (Bonelli et al., 2012). The extent to which changes in religious involvement have contributed to recent increases in depressive symptoms among adolescents is unclear. Further, the effect of religion on depressive symptoms is unlikely to be uniform. Nationally representative samples with data in recent years are needed to investigate the association of religious involvement with depressive symptoms. This is particularly needed among adolescents sampled across a wide swath of historical time to document trends in these factors and investigate whether declining religious engagement contributes to increasing depressive symptoms.

Additionally, geographic area may underlie religious effect heterogeneity, as patterns of religious involvement and affiliation, and the social importance of religion, vary widely across the USA. Adolescent religiosity, specifically religious attendance and personal importance, is substantially higher in the southern USA compared to other areas, with particularly high concentrations of Christian faith affiliation (Wallace et al., 2003). Regional differences in the social significance of religion may modify the strength of any potential associations between religious factors and mental health outcomes.

We used national data collected from 1991 to 2019 to examine relationships between religious factors (i.e., attendance of religious services and whether religion is personally important) and depressive symptoms among US students in grades 8, 10, and 12. We explored possible regional differences in this relationship, and the extent to which trends in depressive symptoms were attributable to the changing landscape of religiosity among adolescents.

Methods

The 1991 through 2019 Monitoring the Future (MTF) surveys included nationally representative, annual, cross-sectional surveys of school-attending adolescents (Johnston et al., 2019) Schools were selected under a multi-stage random sampling design and invited to participate for two years. Schools that declined participation were replaced with schools with similar geographic location, size, and urbanicity. By grade and year, student response rates ranged from 79% (e.g., grade 12, 2017) to 91% (e.g., grade 8, 2012). Self-administered questionnaires were given to students. Since surveys are only distributed to students in grades 8, 10, and 12, the two years of data from a given school reflect different samples of students. The Institutional Review Boards of University of Michigan and Columbia University approved the study protocol and analytic aims, respectively. The final analytic sample included 417,540 respondents, approximately 15,000 per year, who were each assessed at a single time point and assigned to various versions of the survey, or “subforms,” that included relevant study variables. No data on religious variables were available for one state from 1997 onward. Characteristics of the analytic sample are provided in Appendix Table 3.

Measures

Religion was queried across service attendance, importance, and denomination. (1) “How often do you attend religious services?”: “Never,” “Rarely,” “Once or twice a month,” “About once a week or more”; (2) “How important is religion in your life?”: “Not important,” “A little important,” “Pretty important,” and “Very important.” For primary analyses, the response options were collapsed into “Not important” vs “Any importance,” as previous analyses of this variable have suggested stark increases in adolescents reporting that religion is “not important” (Twenge et al., 2015). We hypothesized that the potential psychological benefits of religious attendance may not translate to adolescents endorsing religion as “not important.” Sensitivity analyses utilizing all four distinct religious importance groups built on these analyses for further nuance. These two items, religious attendance and dichotomized religious importance, were combined to create eight groups, ranging from “attending services weekly and feels religion is personally important” to “never attends religious services and does not feel religion is personally important.” The remaining religion item “What is your religious preference?”, which addresses a respondent’s religious denomination with 18 response options, was used as a covariate.

Four items were used to measure depressive symptoms, with responses ranging from 1 (Disagree) to 5 (Agree) with the following statements: “Life often seems meaningless,” “The future often seems hopeless,” “It feels good to be alive,” and “I enjoy life as much as anyone.” The latter two questions were reverse coded. Scores were summed, ranging from 4 to 20 with a mean of 7.87 (95% CI 7.85, 7.90) and median of 7.0, indicating that the mean and median scores were close to the “disagree somewhat” response. This scale exhibited sufficient internal consistency in our study. (Cronbach’s alpha for each grade and each year varied between 0.72 and 0.83.)

This scale is based on the Bentler Medical and Psychological Functioning Inventory’s scale for depression personality trait ( Newcomb et al., 1981), and these items have been used as a proxy measure of depressive symptoms in prior research (Coley et al., 2019; Maslowsky, Schulenberg, & Zucker, 2014a, 2014b; Maslowsky, Schulenberg, O’Malley, et al., 2014). These items exhibit strong reliability in adolescent samples (Newcomb et al., 1986).

Respondents missing data on one of the four items (2.2%) had their missing item multiply imputed (see Statistical Analysis for details); respondents missing data on 2 + items (12.2%) were excluded due to substantial missingness of other variables. While those excluded for missing depressive symptom data had similar religious characteristics to the adolescents who were included, excluded students featured more adolescents who were male, non-white, and younger (Appendix Table 4). Depressive symptom data and religious variable data for any given respondent were collected concurrently in each yearly cross-sectional survey.

Depressive symptom scores were highly right-skewed; thus, we created dichotomies. Because there is no empirically validated clinical cut score, we used a range of potential cut scores, including > 10 (24.4% of sample), > 12 (11.9% of sample), and > 15 (4.7% of sample). These roughly correspond to approximately the 75th, 90th, and 95th percentiles.

Statistical Analysis

We conducted survey-weighted logistic regression analyses to examine the association between religious importance/attendance category and depressive symptoms. Survey weights were used to approximate a random distribution of the target population accounting for probability of school and sample selection. Logistic regression was used for binary outcomes, e.g., binary cut scores for high depressive symptoms. These analyses are presented both unadjusted and adjusted for sex (male, female), race/ethnicity (white, Black, Hispanic/Latino, Multiracial, Other), grade (8, 10, 12), religious affiliation/denomination, subform (different versions of survey content given randomly), academic performance (typical self-reported letter grades: A’s, B’s, C’s, D’s), parental education (Less than High School Grad, High School Grad, College Grad), urbanicity (Metropolitan Statistical Area vs not), binge drinking (any past two weeks), marijuana use (any past month), and year in two-year categories (e.g., students sampled in 2018 or 2019 are in the year category 2018–2019).

Missingness of covariates and the depressive symptom outcome ranged from 1.2% (academic performance) to 6.4% (binge drinking) and was handled with multiple imputation by chained equations (k = 5) in Stata 15.1. By utilizing analytic tools from the “mi” set of commands in Stata in conjunction with the “svy” prefix to account for survey weighting, final results were pooled from imputed datasets to account for imputation uncertainty and survey design.

Explaining Trends in Depressive Symptoms

While the above analyses focus on cross-sectional associations, we also estimated the extent to which changes in depressive symptoms over time were attributable to changing religious importance and attendance. To do this, we projected what the trend in depressive symptoms would have been if religious factors were held at their 1991 distribution. We created a projected mean depressive symptom score for all adolescents by year by setting the distributions of religious importance and attendance groups to the level that they were in 1991. All other variables were allowed to vary in order to isolate the specific contribution of changing religion to trends in depressive symptoms. To calculate the projected mean depressive symptom scores for each year from 1991 to 2019, we computed the year-specific mean depressive symptom score for each of the eight religious attendance/importance groups and combined them per their 1991 proportions.

To illustrate the difference between the observed and projected mean, the observed 2019 overall mean in depressive symptoms would equal the sum of each religious attendance/importance group prevalence in 2019 times that group’s mean depressive symptom score in 2019. The projected mean simply takes that same formula but replaces the 2019 prevalences with the 1991 prevalences to illustrate the overall mean that would have been observed if the size of these religious attendance/importance groups was static since 1991. This approach has been used elsewhere to examine adolescent health using Monitoring the Future data (Miech et al., 2020).We took a similar approach with total depressive symptom score > 15. We have used this method in other analyses (Kreski et al., 2021).

Examining Temporal Relationships Between Depressive Symptoms and Religious Factors at the Population Level

Using overall prevalence of religious factors and average depressive symptoms among all adolescents by year, we assessed whether annual changes in religious salience/service attendance prevalence predict future changes in depressive symptoms, or vice versa, using lagged analysis. For each year, we estimated the overall prevalence of two religious outcomes (monthly or higher religious service attendance and religion being personally unimportant) as well as the overall depressive symptom mean score. We regressed annual mean depressive symptom score onto each annual religious factor in separate models (i.e., assessing whether mean depressive symptom score in Year X is associated with religious service attendance in Year X). We then created additional models where we lagged the prevalence of the religion variables one year at a time, from three years before the depressive symptom score (i.e., assessing whether mean depressive symptom score in Year X is associated with religious service attendance in Year X-3) through three years after the observed symptom score (i.e., assessing whether mean depressive symptom score in Year X is associated with religious service attendance in Year X + 3) to examine how that connection changes. When the time lag is before the observed symptom score, each estimate can be interpreted as the extent to which religious variables predict later depressive symptoms. When the time lag is after the observed symptom score, each estimate can be interpreted as the extent to which depressive symptoms are connected to later religious factors. This helps to assess the possibility that shifts in one trend are linked to later shifts in another.

Sensitivity Analyses

Sensitivity analyses of the overall associations between religious factors and depressive symptoms examined the associations using four levels of religious importance (“Not important,” “A little important,” “Pretty important,” and “Very important”), rather than the dichotomization between “Not important” and “Any level of importance.” Additional sensitivity analyses were stratified by region (Northeast, North Central, South, and West).

Results

Trends

Religious importance and attendance were mostly stable until the early 2000s, when the percentage of students attending religious services at least monthly declined from a peak of 58.0% in 2002 to 43.9% in 2019, and the percentage of students who felt religion was personally important declined from a peak of 88.0% in 2000 to 75.5% in 2019 (Fig. 1). The group who felt religion was “a little” important stayed mostly static in proportion, always close to its average of 24.5%, whereas there were downward trends for those who felt religion was “pretty” important (peak, 1991: 32.9% to 2019: 26.4%) and those who felt religion was “very” important (peak, 2002: 34.0% to 2019: 21.8%). On average, attending religious services at least monthly declined by 0.40 percentage points per year, and the personal importance of religion declined by 0.42 percentage points per year. Depressive symptoms increased, especially since 2012.

The Relationship Between Religious Factors and Depressive Symptoms

Personal importance of religion has a clear link to adolescent depressive symptoms, as adolescents who say religion is not personally important have 2.94 times the odds of high depressive symptoms (score > 15) compared to peers who say religion is important (95% CI 2.83, 3.05). The role of religious attendance, however, varied based on this personal importance of religion. For adolescents who felt that religion was personally important, less frequent service attendance was consistently associated with higher depressive symptoms. Compared to adolescents who attended weekly services, those who never attended religious services had 2.23 (Table 1, 95% CI 2.08, 2.39) times the odds for high depressive symptoms. Adjustment for demographics, substance use, and other personal characteristics attenuated this association (Table 1, aOR [adjusted odds ratio] = 1.50, 95% CI 1.39, 1.61).

However, this pattern did not hold for students who felt that religion was not important. Among these adolescents, across all cut scores examined [to be discussed later], the highest odds of depressive symptoms were observed among weekly attendees of religious services. This was 5.60 (Table 1, 95% CI 4.96, 6.31) times the odds of depressive symptoms (score > 15) compared to those who felt that religion was personally important and attended church equally as often. These relationships were robust to adjustment for demographic characteristics, substance use, and other personal characteristics, including religious group affiliation (Table 1, aOR = 4.31, 95% CI 3.79, 4.89). For adolescents who felt religion was unimportant, the lowest depressive symptoms were consistently exhibited among those attending religious services “rarely.” The interaction between religious attendance and importance indicated that the magnitude of association for religious attendance varied across levels of religious importance, F(3, 5596.3) = 112.51, p < 0.001.

Sensitivity Analyses

Sensitivity analyses were conducted with different thresholds (> 10 and > 12) to examine the consistency of the relationships between religious factors and depressive symptoms (Appendix Table 5). Patterns were similar to those in the main analysis. Additionally, sensitivity analyses compared all categories of personal importance of religion to examine nuance in the connections between religious attendance and depressive symptoms (Appendix Tables 6 and 7). The lowest depressive symptoms were observed among groups with concordant or near-concordant religious importance and attendance (e.g., Very Important/Weekly Attendance, Pretty Important/Monthly Attendance, down to Not Important/Rare Attendance).

Geographic Heterogeneity

Geographic region was examined as a potential modifier of the connection between religious factors and depressive symptoms. The most notable regional differences were greater religious attendance and importance concentrated in the southern USA. Adolescents in the South had a higher prevalence of weekly religious attendance (43.4%) and religion being very important (37.8%) than any other region (p < 0.001 for both attendance and importance) (Appendix Table 8). While prevalence of high depressive symptoms (score > 15) differed by region (p < 0.001), the range of prevalences was narrow, from 4.4% in the South to 5.1% in the West.

We stratified the results by region to better understand the magnitude of differences across region. Weekly attendees of religious services who felt religion was personally unimportant in the South had 6.67 (Table 2, 95% CI 5.51, 8.07) times the odds of high depressive symptoms compared to weekly attendees who felt religion was important, a relationship that remained after adjustment (Table 2, aOR = 4.90, 95% CI 3.97, 6.04). Still, while this relationship was strong, the number of adolescents impacted was small, given that the group attending services weekly who felt that religion was personally unimportant represents less than 1% of the adolescents examined.

Explaining Trends in Depressive Symptoms

We additionally documented how much the change in religious importance and attendance explains the increase in depressive symptoms in the USA. Figure 2 shows the observed and projected depressive symptom scores from 1991 to 2019. The gap between observed and projected depression scores has been widening since the early 2000s. Depression scores dropped from 1991 to 2012. The decrease in mean depressive symptoms scores would have been 0.53 points if prevalence of religious factors was static since 1991, rather than the observed decrease of 0.41 points, meaning the drop would have been 28.2% larger. Depression scores increased from 2012 to 2019. The increase in mean depressive symptoms score would have been 1.33 points, as opposed to the observed increase of 1.53 points, meaning this increase would have been 13.0% smaller. Over the entire study period from 1991 to 2019, the increase in depressive symptoms would have been 0.80 points, rather than the observed increase of 1.12 points. This means that, if the distribution of the eight attendance–religious importance groups was stable over time, the overall increase would have been 28.2% lower. Appendix Fig. 3 shows a similar trend for a binary depressive symptom cut score (> 15).

Population-Level Temporality through Lagged Analysis

When the time lag is before the observed symptom score (top three rows, Appendix Tables 9 and 10), religion variables predict later depressive symptoms. For instance, a one percentage point increase in the prevalence of religion being personally unimportant predicts a 0.0854-point increase in depressive symptoms three years later. However, when the time lag is after the observed symptom score (bottom three rows), where depressive symptoms are linked to later prevalence of religious factors, the relationship is much weaker. Estimates decrease in size with each additional year of lag, reaching non-significance after just one or two years. This further emphasizes the likelihood that the direction of the association, at least at the population level, is religious factors influencing depressive symptoms, not the reverse.

Discussion

The association between religious attendance and reduced depression and depressive symptoms has been documented in previous research (Balbuena et al., 2013; Braam & Koenig, 2019; Dew et al., 2008; Maselko et al., 2009; Vanderweele, 2017). Among adolescents, our findings indicate that variation based on personal importance is an important qualifying consideration. In a large nationally representative sample of adolescents from 1991 to 2019, for adolescents who report that religion is important to them, less frequent religious attendance is associated with higher depressive symptoms. For adolescents who do not report religion as important, the relationship was the opposite, with weekly service attendees having higher odds of depressive symptoms than any other group. These results suggest that concordance between importance of religion and religious service attendance is beneficial. This is true at all levels of importance; e.g., among those who say religion is only “a little” important, attending religious services rarely or monthly was associated with lower depressive symptoms than attending weekly or never.

It is also worth considering alternative interpretations, however. It is unclear whether structured religious involvement leads to changes in mental health, or whether reverse causation explains this association, with worsening depressive symptoms and hopelessness leading people to disengage from their religious communities and beliefs as they do with other social activities (Ang et al., 2017). Some studies have addressed these relationships with longitudinal data (Balbuena et al., 2013; Braam & Koenig, 2019; Garssen et al., 2021; Li et al., 2016; Min et al., 2016; Strawbridge et al., 2001; Van Voorhees et al., 2008; VanderWeele et al., 2016), which can clarify this temporal order and control for confounding due to baseline depression or other factors. Among these longitudinal studies, the most common outcome is religious involvement predicting lower depression and depressive symptoms over time, though the strength of this connection diminishes in younger populations. While there is some evidence that depression also influences religious engagement (Li et al., 2016), this relationship is bidirectional and complex, with the potential for a reinforcing loop if lower religious engagement leads to worse mental health, which sustains religious disengagement.

The effect that religious attendance can have on depression operates through a wide variety of mechanisms. At a psychological level, religious involvement may bolster individual coping with life stressors, providing meaning or hope during difficult life events and daily struggles that could otherwise worsen mood (Koenig, 2018; Park, 2005; Siegel et al., 2001). Socially, individuals attending religious services can have access to a community for social support, which might further protect against depression or other adverse mental health outcomes (Hodges, 2002; Koenig, 2018; Schnittker, 2019).

For those who felt religion was not important, depressive symptoms were lowest in the group who rarely attended religious services. Among these adolescents, attending services more frequently, either weekly or monthly, may be the product of caregiver pressure, which might adversely impact their experience of religious participation. Our results suggest that benefits of religious attendance on depressive symptoms for adolescents are not universal, and depend on how important religion is to the adolescent.

It is worth noting that the odds of depressive symptoms were higher for all “not personally important groups” compared to their “personally important” counterpart. These differences may be due to fewer coping resources and lessened social support (Hodges, 2002; Koenig, 2018), indicating that efforts to improve adolescent health may benefit from considering the strengths of religious involvement. Religious engagement may support forgiveness and gratitude, and those attending religious services may hear messages surrounding other health behaviors, like avoiding substance use, all of which can support mental health (Levin, 2010).

Strengthening the social and coping resources outside of religion available to adolescents might be especially helpful when these adolescents have other identities that render them marginalized by some religious groups. For instance, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) adolescents may be compelled to attend religious services that could contain anti-LGBT messaging, and this group already faces higher rates of depression and depressive symptoms than their heterosexual peers (Luk et al., 2018; Reisner et al., 2016). Accounting for the unique experiences of marginalized people is a priority, ensuring both accuracy and representation within results.

Geographic differences in the magnitude of these associations were evident, with particularly strong associations in the southern USA. It may be that the added social emphasis on religion in certain regions, such as the southern USA, renders those who do not emphasize religion as isolated or stigmatized. People who are non-religious often face discrimination socially, especially in parts of the southern USA, and this social stigma may carry over to individuals who consider religion personally unimportant (Cragun et al., 2012). Further analyses might take a fine-grained spatial approach to these associations between religion and mental health, nuance that is not currently possible with these data.

Lastly, a substantial component of the changing trends in depressive symptoms appears attributable to the changing landscape of religious attendance and importance. Had trends in these religious factors stayed flat since 1991, the overall increase in depressive symptoms would have been attenuated, more noticeably so in the past decade. Declines in religious involvement explain about 28% of the overall increase in depressive symptoms from 1991 to 2019 among US adolescents. Even though this is a substantial part of the increase, over 70% of that increase remains unexplained, indicating that other mechanisms explain increases in adolescent depressive symptoms. Even within the 28% that is explained, we do not know the specific component of religious involvement that is most important to mental health well-being, or the underlying causes of why religious factors are declining. Still, for adolescents who do feel that religion is important, promoting religious attendance concordant with the level to which religion is personally important may provide valuable psychological benefits. Religion can be more thoroughly integrated into discussions surrounding adolescent mental health.

The present study was strengthened by the use of a large sample of adolescents across a wide age range. Examining religious attendance and importance simultaneously while stratifying by region allowed for a nuanced characterization of patterns and differences in depressive symptom outcomes. While there was no clinically defined cut score for the depressive symptoms scale, results are consistent across multiple cut scores. Patterns were particularly strong at higher cut scores, suggesting that findings may be especially relevant for more severe cases of depressive symptoms.

Limitations are noted. Given the cross-sectional nature of these data, the causal directions of observed associations cannot be established, though our lagged analyses suggest that it is more likely religion informing depressive symptoms, rather than the reverse. There may be other religious factors that contribute to adolescent mental health that could not be assessed here. These include private spirituality and discrimination, either due to religious identity or from a religious institution due to other personal identities. Nuanced changes in the nature and content of religious services could not be assessed with these data. Furthermore, there was no information on reasons for religious attendance or importance, which might provide additional context. We were unable to address parental or caregiver religiosity, or discordance between that factor and adolescent religiosity, which may have psychosocial impacts.

Results may vary among adolescents outside of grades 8 through 12, youth who are not in school, or non-US youth. Results may also vary across the lifespan, as trajectories of religion moving from adolescence into adulthood show significant changes, like lower attendance but higher importance of religion over time (Dew et al., 2020).

The items examining depressive symptoms within this study had certain limitations in domain coverage. The depression items cover anhedonia and hopelessness, but not depressed mood, sleep or appetite disturbances, worthlessness, guilt, fatigue, or other cardinal symptoms of depression, and therefore, the findings might vary with a broader more robust measure of depressive symptoms. However, trends in depressive symptoms were consistent with other national sources of information on depressive episodes (Mojtabai et al., 2016), underscoring that these measures are consistent with established indicators of adolescent mental health. We also lacked information on whether adolescents had received treatment for their mental health problems. However, only a minority of individuals with depression receive treatment (Hasin et al., 2005), suggesting that treatment is unlikely to have had a large impact on the sample’s symptom scores.

Conclusion

The relationship between religious involvement and attendance with depressive symptoms among adolescents is nuanced. For adolescents who find their faith to be personally important, promoting and providing space for religious service attendance may be an effective way to improve their mental health. For adolescents who do not feel religion to be personally important, other approaches may be useful, but these approaches can learn from the strengths of religious involvement, fostering social support and coping strategies. Public health and counseling professionals should encourage effective coping among adolescents directly with efforts to reduce maladaptive coping behaviors, such as self-blame or behavioral disengagement, and promote effective behaviors, such as coping that incorporates acceptance and cognitive reappraisal of stressors (Compas et al., 2017; Horwitz et al., 2011). The landscape of adolescent religiosity has been changing over several years, underscoring the importance of engaging vulnerable populations with helpful strategies directly and highlighting the research challenges of exploring the complex relationships between religion and mental health.

Data Availability

Data are available through Monitoring the Future, which is largely publicly available.

Code Availability

SAS code is not available, kept in secure data enclave under MTF guidance.

References

Ang, Y. S., Lockwood, P., Apps, M. A. J., Muhammed, K., & Husain, M. (2017). Distinct subtypes of apathy revealed by the apathy motivation index. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169938

Balbuena, L., Baetz, M., & Bowen, R. (2013). Religious attendance, spirituality, and major depression in Canada: A 14-year follow-up study. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371305800408

Bonelli, R., Dew, R. E., Koenig, H. G., Rosmarin, D. H., & Vasegh, S. (2012). Religious and spiritual factors in depression: Review and integration of the research. Depression Research and Treatment. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/962860

Bonelli, R. M., & Koenig, H. G. (2013). Mental disorders, religion and spirituality 1990 to 2010: A systematic evidence-based review. Journal of Religion and Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-013-9691-4

Braam, A. W., & Koenig, H. G. (2019). Religion, spirituality and depression in prospective studies: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.06.063

Coley, R. L., O’Brien, M., & Spielvogel, B. (2019). Secular trends in adolescent depressive symptoms: Growing Disparities between advantaged and disadvantaged schools. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01084-1

Compas, B. E., Jaser, S. S., Bettis, A. H., Watson, K. H., Gruhn, M. A., Dunbar, J. P., Williams, E., & Thigpen, J. C. (2017). Coping, emotion regulation, and psychopathology in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychological Bulletin. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000110

Cotton, S., Zebracki, K., Rosenthal, S. L., Tsevat, J., & Drotar, D. (2006). Religion/spirituality and adolescent health outcomes: A review. Journal of Adolescent Health. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.10.005

Cragun, R. T., Kosmin, B., Keysar, A., Hammer, J. H., & Nielsen, M. (2012). On the receiving end: Discrimination toward the non-religious in the United States. Journal of Contemporary Religion. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537903.2012.642741

Dew, R. E., Fuemmeler, B., & Koenig, H. G. (2020). Trajectories of religious change from adolescence to adulthood, and demographic, environmental, and psychiatric correlates. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000001154

Dew, R. E., Daniel, S. S., Armstrong, T. D., Goldston, D. B., Triplett, M. F., & Koenig, H. G. (2008). Religion/spirituality and adolescent psychiatric symptoms: A review. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-007-0093-2

Fruehwirth, J. C., Iyer, S., & Zhang, A. (2019). Religion and depression in adolescence. Journal of Political Economy. https://doi.org/10.1086/701425

Garssen, B., Visser, A., & Pool, G. (2021). Does Spirituality or Religion Positively Affect Mental Health? Meta-analysis of Longitudinal Studies. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 31(1), 4–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508619.2020.1729570

Hasin, D. S., Goodwin, R. D., Stinson, F. S., & Grant, B. F. (2005). Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcoholism and related conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1097

Hodges, S. (2002). Mental health, depression, and dimensions of spirituality and religion. Journal of Adult Development. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015733329006

Horwitz, A. G., Hill, R. M., & King, C. A. (2011). Specific coping behaviors in relation to adolescent depression and suicidal ideation. Journal of Adolescence. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.10.004

Johnston, L. D., Miech, R. A., O’Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., Schulenberg, J. E., & Patrick, M. E. (2019). Monitoring the Future: National survey results on drug use 1975–2018. 2018 Overview: Key findings on adolescent drug use. The National Institute on Drug Abuse at The National Institutes of Health. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED594190.pdf

Keyes, K. M., Gary, D., O’Malley, P. M., Hamilton, A., & Schulenberg, J. (2019). Recent increases in depressive symptoms among US adolescents: Trends from 1991 to 2018. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01697-8

Koenig, H. G. (2018). Religion and mental health: Research and clinical applications. Elsevier Academic Press. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2018-00765-000

Kreski, N., Chen, Q., Olfson, M., Cerdá, M., Hasin, D. S., Martins, S. S., Mauro, P. M., & Keyes, K. M. (2021). Adolescent time use and associations with depressive symptoms from 1991 to 2019 among US adolescents. American Journal of Epidemiology (Under Review).

Levin, J. (2010). Religion and mental health: Theory and research. International Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies. https://doi.org/10.1002/aps.240

Li, S., Okereke, O. I., Chang, S. C., Kawachi, I., & VanderWeele, T. J. (2016). Religious service attendance and lower depression among women—a prospective cohort study. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-016-9813-9

Lu, W. (2019). Adolescent depression: National trends, risk factors, and healthcare disparities. American Journal of Health Behavior. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.43.1.15

Luk, J. W., Gilman, S. E., Haynie, D. L., & Simons-Morton, B. G. (2018). Sexual orientation and depressive symptoms in adolescents. Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-3309

Maselko, J., Gilman, S. E., & Buka, S. (2009). Religious service attendance and spiritual well-being are differentially associated with risk of major depression. Psychological Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291708004418

Maslowsky, J., Schulenberg, J. E., O’Malley, P. M., & Kloska, D. D. (2014). Depressive symptoms, conduct problems, and risk for polysubstance use among adolescents Results from US national surveys. Mental Health and Substance Use Dual Diagnosis. https://doi.org/10.1080/17523281.2013.786750

Maslowsky, J., Schulenberg, J. E., & Zucker, R. A. (2014b). Influence of conduct problems and depressive symptomatology on adolescent substance use: Developmentally proximal versus distal effects. Developmental Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035085

Miech, R., Keyes, K. M., O’Malley, P. M., & Johnston, L. D. (2020). The great decline in adolescent cigarette smoking since 2000: consequences for drug use among US adolescents. Tobacco Control, 29(6), 638–643. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055052

Min, J., Ailshire, J., & Eileen, C. (2016). Social engagement and depressive symptoms: Do baseline depression status and type of social activities make a difference? Age and Ageing. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afw125

Mojtabai, R., Olfson, M., & Han, B. (2016). National trends in the prevalence and treatment of depression in adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1878

Newcomb, M. D., Huba, G. J., & Bentler, P. M. (1981). A multidimensional assessment of stressful life events among adolescents: Derivation and correlates. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136681

Newcomb, M. D., Huba, G. J., & Bentler, P. M. (1986). Life change events among adolescents: An empirical consideration of some methodological issues. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-198605000-00004

Park, C. L. (2005). Religion as a meaning-making framework in coping with life stress. Journal of Social Issues. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2005.00428.x

Reisner, S. L., Katz-Wise, S. L., Gordon, A. R., Corliss, H. L., & Austin, S. B. (2016). Social epidemiology of depression and anxiety by gender identity. Journal of Adolescent Health. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.04.006

Schnittker, J. (2019). Religion, social integration, and depression in Europe: Evidence from the European Social Survey. Social Science and Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112376

Siegel, K., Anderman, S. J., & Schrimshaw, E. W. (2001). Religion and coping with health-related stress. Psychology and Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440108405864

Strawbridge, W. J., Shema, S. J., Cohen, R. D., & Kaplan, G. A. (2001). Religious attendance increases survival by improving and maintaining Good health behaviors, mental health, and social relationships. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15324796ABM2301_10

Twenge, J. M., Exline, J. J., Grubbs, J. B., Sastry, R., & Campbell, W. K. (2015). Generational and time period differences in American adolescents’ religious orientation, 1966–2014. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0121454

Van Voorhees, B. W., Paunesku, D., Kuwabara, S. A., Basu, A., Gollan, J., Hankin, B. L., Melkonian, S., & Reinecke, M. (2008). Protective and vulnerability factors predicting new-onset depressive episode in a representative of US adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.11.135

VanderWeele, T. J. (2017). Religion and health: A synthesis. In M. J. Balboni, & J. R. Peteet (Eds.), Spirituality and religion within the culture of medicine: From evidence to practice (pp. 357–401). Oxford University Press. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2017-20091-021

VanderWeele, T. J., Jackson, J. W., & Li, S. (2016). Causal inference and longitudinal data: A case study of religion and mental health. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1281-9

Wallace, J. M., Forman, T. A., Caldwell, C. H., & Willis, D. S. (2003). Religion and US secondary school students: Current patterns, recent trends, and sociodemographic correlates. Youth and Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X03254564

Funding

These analyses are funded by Grant R01DA048853 (PI: Keyes) and with support from the Columbia Center for Injury Science and Prevention (R49-CE003094). Additionally, Dr. Martins reports funding from Grant R01DA037866, and Dr. Hasin reports funding from Grant R01DA048860. Funders had no role in the conduct of research or the preparation of this article. Funders had no role in study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the article, or in the decision to submit it for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No potential competing interest was reported by the authors.

Ethical Approval

The Monitoring the Future study is approved by the IRB of University of Michigan.

Informed Consent

Parents were informed of the study and provided the option to decline participation on their child’s behalf.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

See Fig. 3 and Tables 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kreski, N.T., Chen, Q., Olfson, M. et al. Explaining US Adolescent Depressive Symptom Trends Through Declines in Religious Beliefs and Service Attendance. J Relig Health 61, 300–326 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01390-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01390-8