Abstract

In this article, we examine the influence of religion on health and life satisfaction while controlling for an extensive range of demographic characteristics and life conditions—marital satisfaction, job satisfaction, financial stress, and social resources—using data drawn from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey. Our findings suggest that, on average, high levels of faith and attendance at religious services are associated with lower health. In contrast, however, we find no relationship between high levels of faith, attendance, and life satisfaction. Further research is required to unravel how faith and attendance influence health and life satisfaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the last 20 years, researchers have devoted considerable effort toward unraveling the association between religion, health, and subjective well-being. Much of this research, which emanates from the USA, indicates that an array of religious dimensions (e.g., affiliation, attendance, and strength of belief) influence health and subjective well-being (Keyes and Reitzes 2007; Eliassen et al. 2005; Larson and Larson 2003; Brooks et al. 2018; Banthia et al. 2007; Bluvol and Ford-Gilboe 2004; Ellison 1991, 2010; Green and Elliott 2010; Doane and Elliott 2016; Rizvi and Hossain 2017; Şenel 2018; Craig et al. 2018; Ngamaba and Soni 2018; Ahaddour and Broeckaert 2018; Dilmaghani 2018).

Perhaps, the most often-studied dimension of religion is the influence that frequency of attendance at religious services has on health and subjective well-being. On this note, many studies have observed a statistically significant positive association between attendance at religious services and subjective well-being (e.g., Headey et al. 2010; Keyes and Reitzes 2007; Francis and Kaldor 2002; Strawbridge et al. 2001; Ellison et al. 1989; Pollner 1989) although this finding is not universal (e.g., Dezutter et al. 2006; Schnittker 2001). Evidence from other studies suggests that social resources and support networks may mediate the positive association between attendance and subjective well-being (e.g., Kortt et al. 2015; Lim and Putnam 2010). Also, attendance at religious services has been linked to improved health outcomes (e.g., Ellison et al. 2001; Strawbridge et al. 2001).

There is also evidence to suggest that other religious dimensions (i.e., religious identity, the strength of belief, and frequency of prayer) may influence health and subjective well-being. For instance, religious identity (i.e., closely identifying as being a member of a religious group or denomination) has also been linked to higher levels of health (e.g., Wink et al. 2005) and subjective well-being (e.g., Greenfield, and Marks 2007; Keyes and Reitzes 2007; Schnittker 2001; Ellison 1991). Some studies have also found that frequency of private prayer is positively associated with health (e.g., Banthia et al. 2007; Ellison et al. 2001) and subjective well-being (e.g., Byrd et al. 2000; Francis and Kaldor 2002). Moreover, individuals who identify as being religious (i.e., the strength of belief) tend to report having higher levels of mental and physical health (e.g., Keyes and Reitzes 2007; Schnittker 2001; Wink et al. 2005) as well as higher levels of subjective well-being (e.g., Gautherier et al. 2006).

Green and Elliott (2010, p. 149), however, make the critical point that only a handful of studies that have examined the association between religion, health, and subjective well-being explicitly include controls to account for “work and family conditions,” which are the “two domains of life that are arguably more important determinants of health and well-being than religion for most people.” Employing data drawn from the 2006 General Social Survey, Green and Elliott (2010) estimated the association between religion, health, and subjective well-being while controlling for a range of work and family conditions. The key results from their study suggest that respondents who identified as being religious tended to report higher levels of health and subjective well-being. They also found that individuals with more liberal religious beliefs reported having better health but found that individuals with more fundamental religious beliefs reported being more content with life.

However, Green and Elliott (2010) also note that comparatively little research has been undertaken on the association between liberal versus fundamental religious beliefs and its attendant influence on health and subjective well-being. Even though limited research has been conducted in this area, there is a related strand of literature that examines differences in the health outcomes between liberal and more fundamental religious groups within a particular religious denomination. For example, there is some evidence to suggest that more fundamentalist Christians in the USA may have more “depressive symptoms and higher levels of religious coping” (Nooney and Woodrum 2002, p. 366) than those Christians who were classed as moderate or liberal. In contrast, a study Sethi and Seligman (1993, p. 256) of 623 US adherents found that members of fundamentalist religious groups “were significantly more optimistic… than those from moderate religions, who were in turn more optimistic than liberals.” This is particularly relevant in the current context given that optimism has been found to be positively correlated with mental and physical well-being (Scheier and Carver 2006; Plomin et al. 1992).

Thus, against this background, we contribute to the existing body of literature by examining this issue using data sourced from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey. The HILDA survey is one of the largest representative surveys in Australia to collect information on religiosity (i.e., affiliation, attendance, and importance) as well as detailed demographic and economic information on its respondents. In essence, the HILDA survey provides us with a unique opportunity to explore how religion influences health and subjective well-being while controlling for: (i) a range of conventional demographic characteristics (e.g., age, income, gender, employment, and so on); and (ii) work and family conditions outside the religious environment (i.e., marital satisfaction, job satisfaction, financial stress, and social resources). In addition to religious affiliation, our measures of attendance at religious services (attendance) and the importance of religion in one’s life (faith) allows us to tap into the domains of ‘religious activities’ and ‘religious identity,’ respectively. Moreover, defining high levels of attendance and faith can also be used as a proxy to isolate the influence that more fundamental—or conservative—religious practices and beliefs have on health and subjective well-being.

Taking account of the above, we expect that there will be a statistically significant positive association between our measures of religiosity (i.e., attendance and faith) and our measures of health and subjective well-being. In exploring this issue, our study contributes to the literature in a number of ways. First, we examine the association between religion, health, and life satisfaction by explicitly including an array of controls to account for a range of life conditions—marital satisfaction, job satisfaction, financial stress, and social resources—that are external to the religious environment. Second, given that our data are drawn from a large representative household panel survey, it affords us the opportunity to control for period effects (or trends over time). Finally, we present—to the best of our knowledge—the first empirical results for Australia, which provides additional insights on a topic that has predominantly been the focus of scholars from the USA.

Data and Empirical Strategy

The data employed in this study was sourced from the HILDA survey, which is Australia’s first nationally representative household panel. The HILDA survey commenced in 2001 (Wave 1) and was based on a national probability sample of households with a significant emphasis on families, income, employment, and subjective well-being. Wave 1 was comprised of 7696 households and 13,696 individuals. A multi-stage sampling strategy was used to identify and select participating households, and a response rate of 66% was achieved. Within each selected household, information was collected from each household member aged 15 and over, using a combination of face-to-face and self-assessed questionnaires. In Wave 1, 92% of adults provided an interview and, in each successive wave, the previous wave on wave response rates was between 87% and 95%. Over time, changes in the household composition—along with a top-up sample in Wave 11—have increased the number of survey respondents.

In this study, we focus our analysis on participants aged between 18 and 85 years from the 2004, 2007, 2010, and 2014 waves of the HILDA survey, which has collected information on religion (i.e., affiliation, attendance, and importance) in addition to information on general health and life satisfaction. The primary advantage of using the HILDA survey is that it is one of the largest representative household surveys in Australia to routinely collect data on religion as well as detailed demographic and economic information on its respondents. Our ensuing regression analysis is based on a final analytic sample of 43,355 respondents.

The dependent variables used on our regression analysis were either: (i) general health or (ii) life satisfaction. General health was measured using the transformed general health score from the Short Form Health Survey or SF-36. The SF-36 has been designed to measure and assess an individual’s health status across eight domains—vitality, physical functioning, bodily pain, general health perceptions, physical role functioning, emotional role functioning, social role functioning, and mental health—and the score from each domain is transformed into a 0–100 scale, where higher scores represent a higher level of general health (Ware et al. 1993). Life satisfaction is assessed using the following question: “All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life?” Participants are then asked to: “Pick a number between 0 and 10 to indicate how satisfied you are” and that “the more satisfied you are, the higher the number you should pick.” Responses range from 0 (totally dissatisfied) to 10 (totally satisfied). There is some evidence to suggest that this measure of subjective well-being has been shown to be positively correlated with other more objective measures of happiness like frowning and smiling (Frey and Stutzer 2002).

With respect to demographic characteristics, we controlled for age in years, gender (1 = female; 0 = otherwise), financial year disposable income, employment status (1 = employed; 0 = otherwise), marital status (1 = legally married; 0 = otherwise), years of education, whether the respondent was Indigenous (1 = Indigenous; 0 = otherwise), plus an indicator variable for year. We coded years of education as the highest year of completed schooling (if the respondent had no post-school qualifications, then less than eight years of schooling was coded as eight years). Post-school qualifications were coded as follows: masters/doctorate = 17 years; graduate diploma/certificate = 16 years; bachelor degrees = 15 years; diploma = 12 years; and certificate = 12 years.

The above block of demographic variables were included in our analysis given that: (i) age is negatively associated with health (e.g., Green and Elliott 2010); (ii) women, on average, are more religious than men (Ellison 1991); (iii) income is positively associated with health and life satisfaction (Ellison et al. 1989); (iv) full-time employment is positively associated with health (e.g., Lewchuk et al. 2003); (v) married individuals report higher levels of mental and physical health (Suhail and Chaudhry 2004); and (vi) individuals with higher levels of educational attainment report higher levels of mental and physical well-being (e.g., Lyons and Yilmazer 2005).

We used several measures to account for life conditions associated with employment status, marital status, and financial status. For employment status, we included a variable to capture overall job satisfaction, which ranged from totally dissatisfied (0) to totally satisfied (10). For those respondents who were not employed, we substituted the mean job satisfaction score. For marital status, we included a variable to capture martial satisfaction, which ranged from totally dissatisfied (0) to totally satisfied (10). Once again, for those respondents who were not married, we substituted the mean marital satisfaction score. The financial situation of respondents was assessed by including a measure of satisfaction with your financial situation, which ranged from totally dissatisfied (0) to totally satisfied (10). We also included measures to account for a respondent’s level of social resources. More specifically, social resources and networks were assessed using two variables. The first measure of social resources was used to assess the following question: “I seem to have a lot of friends?” Responses to this question ranged from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7). The second measure of social resources was assessed by the following question: “How often do you get together socially with friends/relatives not living with you?” Responses to this question ranged from “less often than once every three months” (1) to “every day” (7).

In Australia, the religious landscape differs considerably from other advanced nations like the USA. On this note, the findings from the 2016 Australian census can be used to assist in the classification of religious categories (Table 1). The majority of Australians do not profess faith in any religion (30.1%), while the most extensive religious cohort comprises of Catholics (22.6%) and Anglicans (13.3%), who are known as Episcopalians in the USA. This leaves a comparatively small group (approximately 15%) of mainly Protestant churches for further classification. The distinction which best represents the remainder of the Christian affiliations is whether they are members of the National Council of Churches (CoCs), which comprises around 9.1% of the population (when Catholics an Anglicans are excluded). Non-CoCs membership, which constitutes around 6.5% of the population, is generally as a result of the church’s prima facie incompatible system of beliefs and relative parochialism.

In the USA, these two religious categories would probably be referred to as mainline churches and conservative churches, respectively. However, the main difference we have made is to exclude Anglicans and Catholics and from the ‘mainline’ classification given their relative size and dominance in the Australian religious landscape. Notably, non-CoC churches tend to be characterized by their rejection of the scientific method and, among other things, their otherworldly focus. Moreover, given the comparatively small proportion of Australians belonging to the other world religions, we elect to analyze this category as a separate religious group.

Thus, against this background, religious affiliation was classified into six categories: (i) no religion; (ii) Catholic; (iii) Anglican; (iv) Council of Churches (comprising Greek Orthodox, Orthodox, Churches of Christ, Lutheran, Uniting Church, and Salvation Army), (v) non-Council of Churches (comprising Jehovah’s Witnesses, Brethren, Seventh-day Adventist, Pentecostal, Mormons, Other Christian, Presbyterian/Reformed, Oriental Christian, Other Protestant, and Baptist), and (vi) non-Christians (comprising Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, and Judaism). In the ensuing regression analysis, ‘no religion’ was selected as the excluded reference group.

To identify and isolate the influence of more fundamental—or conservative—religious beliefs and practices on general health and life satisfaction, we introduced two additional measures. First, we identified those respondents who reported having high levels of faith (1 = high faith; 0 = otherwise). As our measure of religious importance—or faith—ranged from 0 (the least important thing in my life) to 10 (the most important thing in my life), high faith was classified as those respondents who reported a value greater than or equal to 8. Second, we identified those respondents who reported having high levels of attendance at religious services excluding ceremonies like weddings or funerals. The frequency of attendance ranged from never (1) to every day (9). In our subsequent analysis, high attendance was defined as those respondents who reported attending services either “several times a week” or “every day” (1 = high attendance; 0 = otherwise).

To examine the association between religion, health, and life satisfaction, we estimated a series of hierarchical regression models, with general health and life satisfaction as the dependent variables. In our first specification, we only include our demographic variables to explore whether different demographic factors exert differential impacts on health and life satisfaction. In our second specification, we introduce our range of life conditions to control for job satisfaction, marital satisfaction, perceived financial stress, and social resources. In our third specification, we introduce our religious affiliation variable as well as our measures of high faith and high attendance to account for more fundamental religious beliefs and practices. Thus, our most extensive regression specification is:

In Eq. (1), Y is either the respondent’s general health or life satisfaction score, D is a vector of demographic variables (age, gender, income, employment status, marital status, years of education, Indigenous status plus an indicator for year), L is a vector of life conditions (marital satisfaction, job satisfaction, perceived financial stress, frequency of social contact, and number of friends), R is a vector of religious variables (affiliation, high faith, and high attendance), and µ is an error term. We estimated Eq. (1) using ordinary least squares (OLS). Since we observe the same individuals in 2004, 2007, 2010, and 2014, our standard errors are clustered at the individual level to account for within-person serial correlation. We also experimented with using a random effects panel regression model and found that this made very little difference to our results.

Results

In Table 2, we present the definitions, means, and standard deviations of the variables used in our empirical analysis. In our sample, the mean life satisfaction score was 7.88 (SD = 1.45) while the mean general health score was 67.83 (SD = 21.03). Females comprised 52% of the sample, and the mean age was 45.74 years (SD = 16.91). In our sample, 66% of respondents reported being employed, and the mean financial disposable income was $37,400. Also, 56% of our sample were married and had an average of 12.20 (SD = 2.24) years of education. Around 2% of our sample were classified as being of Indigenous heritage (i.e., of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander origin). The average marital satisfaction and job satisfaction scores were 8.29 (SD = 1.41) and 7.63 (SD = 1.34), respectively, while the mean financial satisfaction score was 6.52 (SD = 2.18). The average social support and friends scores were 4.46 (SD = 1.46) and 4.50 (SD = 1.63), respectively.

Regarding religious affiliation, 31% of our sample reported no religious affiliation, while the most significant religious cohorts were comprised of Catholics (24%) and Anglicans (19%). In our sample, 11% of respondents belonged to CoCs while 9% of respondents belonged to non-CoCs. As noted above, these two religious categories would probably be referred to as mainline and conservative churches in the USA. Finally, around 5% of our sample was classified as non-Christians. Also, around 3% of our sample attended religious services several times a week or every day, while 20% of respondents reported that religion was one of the most important things in their life.

In Table 3, we report our regression results for general health. In Model 1, we include our block of demographic variables. The results indicate that age and Indigenous status are negatively associated with health. Previous studies have identified a negative association between age and health and a curvilinear relationship between age and subjective well-being (Mirowsky and Ross 1992; Green and Elliott 2010). On the other hand, being married, employed, more educated, and earning a higher income is positively associated with general health. All variables are statistically significant at the 1% level. Ellison et al. (1989) and Ellison (2010) find similar results.

In Model 2, we introduce our additional set of control variables to account for a range of different life conditions. In the first place, there is a statistically significant positive association between marital satisfaction and health and its introduction attenuates the association between marital status and health.

While there is a statistically significant positive association between job satisfaction and health, it is important to note that the magnitude (and statistical significance) of the employment coefficient is substantial. This suggests that being employed has a more significant impact on health rather than the satisfaction that a respondent derives from being employed. There is also a statistically significant positive association between being satisfied with one’s financial situation and health. Finally, we also observe a positive and statistically significant association between health, the number of friends, and frequency of social interactions.

In Model 3, we introduce our measures of religious affiliation and religiosity (i.e., high attendance and high faith). Concerning religious affiliation, the estimated coefficients indicate that the only statistically significant difference observed was between Anglicans and the excluded reference group of no religion (all remaining religious affiliations were not statistically significant at the 5% level). The results indicate that Anglicans had, on average, a 1-point higher health score compared to individuals reporting no religious affiliation. Regarding ‘mainline/liberal’ versus ‘conservative/fundamental’ religious practices and beliefs, we find that individuals who reported having high levels of faith and attendance had statistically significant lower health scores. In other words, those respondents who reported having relatively more fundamental beliefs and practices had, on average, lower health scores.

In Table 4, we report our regression results for life satisfaction. In Model 1, we regress life satisfaction on our block of demographic controls. The results indicate that age, income, being female, married, and employed is positively associated with life satisfaction. On the other hand, being Indigenous and years of education is negatively associated with life satisfaction (although the magnitude of the education coefficient is rather small). All variables are statistically significant at the 1% level.

In Model 2, we introduce our additional set of control variables to account for a range of different life conditions. The results indicate that marital satisfaction, job satisfaction, and financial satisfaction are positively associated with life satisfaction. All variables are statistically significant at the 1% level. The introduction of the marital satisfaction variable attenuates the association between being married and life satisfaction. The introduction of our financial satisfaction variable also attenuates that association between income and life satisfaction (although, once again, the magnitude of the estimated income coefficient is rather small). This suggests that an individual’s satisfaction with their financial situation—as opposed to their income levels per se—has a more substantial influence on life satisfaction.

Moreover, while job satisfaction is positively associated with higher levels of life satisfaction, being employed per se, is not (as the coefficient on the employment variable is no longer statistically significant). This suggests that the positive effect of employment on life satisfaction is operating or being exerted through job satisfaction. Thus, those individuals who report a higher level of job satisfaction tend to report having higher levels of health and subjective well-being (Suhail and Chaudhry 2004; Green and Elliott 2010). For those who are married, a higher level of marital satisfaction is correlated with a greater level of subjective well-being (Ellison et al. 1989; Ellison 2010). Finally, we also observe a positive and statistically significant association between life satisfaction, the number of friends, and frequency of social interactions.

In Model 3, we introduce our measures of religious affiliation and religiosity. Concerning religious affiliation, the estimated coefficients indicate that the only statistically significant difference was between non-Christians and the excluded reference group (all other religious affiliations were not statistically significant). The results indicate that non-Christians had, on average, a 0.163 lower life satisfaction score compared to individuals reporting no religious affiliation. On this point, Ngamaba and Soni (2018) indicate that Roman Catholics, Protestants, and Buddhists report being more satisfied with their lives than other religious groups. Concerning ‘mainline/liberal’ versus ‘conservative/fundamental’ religious beliefs, we find that there is no association between life satisfaction and high levels of attendance and faith.

Additional Analysis

In estimating the above associations, our high attendance and high faith variables are designed to capture the influence of relatively more ‘conservative/fundamental’ beliefs and practices on health and life satisfaction. However, these dichotomous classifications may mask the overall impact that attendance and faith may have on health and life satisfaction. Thus, to remedy this situation and further unpack our results we re-estimated our most extensive regression equation using a range of alternative measures for attendance and faith.

Concerning attendance, we used two alternative measures: (i) a ‘continuous’ measure of attendance (with scores ranging from 1 to 7); and (ii) a dummy variable for those respondents who ever attended a religious service (1 = ever attended; 0 = otherwise). Regarding faith, we used two alternative measures: (i) a ‘continuous’ measure of faith (with scores ranging from 0 to 10) and (ii) a dummy variable for those respondents reporting some level of faith (1 = some faith; 0 = no faith). Finally, we created a composite religiosity index by summing the Z-scores for attendance and faith. The results using these alternative measures of attendance and faith are reported in Table 5.

Looking across Table 5, we find that there is a strong overall association between faith and health. Our ‘continuous’ measure of faith indicates that there is a statistically significant negative association between increasing levels of faith and health. For our dichotomous measure of faith, the estimated coefficient indicates that there is a statistically significant difference between individuals reporting ‘some faith’ compared to the excluded reference group of individuals reporting ‘no faith.’ Finally, there is a statistically significant negative association between our religiosity index and health. However, for our alternative measures of attendance, we find little evidence of an overall association between attendance and health although our measure of ‘some attendance’ is statistically significant at the 10% level.

In contrast, our principal results in Table 3 indicate that there is a statistically significant negative association between health and high levels of attendance and faith. This suggests that individuals with high attendance levels are more likely to hold ‘conservative/fundamental’ religious beliefs and, subsequently, have higher levels of faith. This is borne out in Table 6, where we present religious affiliation stratified by high faith for those respondents who also reported having high attendance levels. Not surprisingly, nearly 96% of respondents—across all religious affiliations—reported having high levels of faith (conditional on having high levels of attendance at religious services).

Returning to Table 5, we find little evidence of an overall association between life satisfaction, attendance, and faith. The only exception is our dichotomous measure of faith, which indicates that there is a statistically significant difference between individuals reporting ‘some faith’ compared to the excluded reference group but the effect is small. Overall, these results are broadly consistent with our main findings reported in Table 4, which suggests that there is little, if any, compelling evidence of an association between life satisfaction and a high level of attendance and faith.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the association between religion, health, and subjective well-being while controlling for a range of additional life conditions—job satisfaction, marital satisfaction, perceived financial stress, and social resources—that have not traditionally been included in studies of this type (Green and Elliott 2010). Drawing on data from the HILDA survey, we also contributed to the literature by providing—to the best of our knowledge—the first results of this particular issue for Australia.

In essence, our principal results indicate that, on average, high levels of faith and attendance are associated with lower health (Table 3). In contrast, we find no evidence of a relationship between high levels of faith, attendance, and life satisfaction (Table 4). These findings are more likely to be indicative of the influence that more ‘conservative/fundamental’ beliefs and practices have on health and subjective well-being. However, as these dichotomous classifications may mask the overall impact that attendance and faith may have on health and life satisfaction, we re-estimated our most extensive regression model using a range of alternative measures of attendance and faith (Table 5) and found that they were broadly consistent with our principal analysis (Tables 3 and 4).

Concerning the association between religion and health, our results share some similarities with those of Green and Elliott (2010) who also found evidence of a statistically significant negative association between more ‘conservative/fundamental’ religious beliefs and health. One possible explanation for this finding is that individuals with more fundamental beliefs may be less inclined to seek medical attention and instead rely on the power of prayer or divine intervention when it comes to matters of health (Green and Elliott 2010). In contrast, however, we would expect individuals with more liberal religious beliefs and practices to seek medical attention as opposed to relying on the healing hand of a higher power. Another possible explanation is that people with poorer health may be drawn to more fundamentalist religions for comfort and social support, especially given the purported higher levels of optimism (and coping mechanisms) that more fundamentalist religions may offer prospective adherents.

However, in contrast to Green and Elliott (2010), we observe that even after controlling for demographics, life conditions, and religiosity (i.e., high attendance and faith), we still observe that Anglicans, on average, have higher levels of health. This is a curious finding, which may indicate that certain practices and attitudes within the Australian Anglican tradition may be more conducive to a healthier lifestyle. Further research is required to unravel this particular finding.

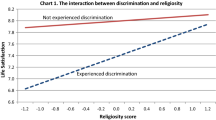

Regarding the association between religion and life satisfaction, our results stand in stark contrast to those of Green and Elliott (2010). Contrary to our expectations, we find little, if any, compelling evidence of an association between religiosity (attendance and faith) and life satisfaction. One possible explanation is that life conditions—at least in the Australian social milieu—have a far greater influence on subjective well-being than religiosity does. This, in part, may reflect the considerable differences between the religious landscapes in Australia and the USA. Moreover, we also find that non-Christians (Buddhists, Muslims, Hindus, and Jews) had, on average, a statistically significant lower level of life satisfaction compared to the excluded reference group of no religion. This finding may be due to the perceived religious discrimination experienced by non-Christians in a predominately Christian country. While we expected that these results might have been primarily concentrated among Australian Muslims, we were unable to identify a Muslim-specific effect, which is probably due to our relatively small non-Christian sample size. Further research is required to understand the underlying rationale behind the lower life satisfaction scores observed for non-Christians.

While our study contributes to the literature on religion, health and life satisfaction, it is limited by the fact that we only use a single measure of health (the SF-36) and subjective well-being. Thus, further studies that make use of multiple health and life satisfaction measures are required (Sinnewe et al. 2014). On this note, our study was also limited by the fact that we only had three measures of religiosity (i.e., affiliation, attendance, and importance) available to us in the HILDA survey. A more detailed religious module would have afforded us the opportunity to capture (and subsequently test) a more comprehensive range of religious dimensions. However, our study does benefit from using a large and representative national survey over multiple periods. More importantly, we found that using a more sophisticated random effects panel regression model made very little difference to our results, which, in turn, provides confidence in the robustness of our results. While further research is required to explore (and unpack) the relationship between religion, health, and life satisfaction, we believe that this would be a fruitful avenue of academic inquiry.

References

Ahaddour, C., & Broeckaert, B. (2018). For every illness there is a cure: Attitudes and beliefs of Moroccan Muslim women regarding health, illness and medicine. Journal of Religion and Health,57, 1285–1303.

Banthia, R., Moskowitz, J. T., Acree, M., & Folkman, S. (2007). Socioeconomic differences in the effects of prayer on physical symptoms and quality of life. Journal of Health Psychology,12, 249–260.

Bluvol, A., & Ford-Gilboe, M. (2004). Hope, health work and quality of life in families of stroke survivors. Journal of Advanced Nursing,48, 322–332.

Brooks, F., Michaelson, V., King, N., Inchley, J., & Pickett, W. (2018). Spirituality as a protective health asset for young people: An international comparative analysis from three countries. International Journal of Public Health,63, 387–395.

Byrd, K. R., Lear, D., & Schwenka, S. (2000). Mysticism as a predictor of subjective well-being. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion,10, 259–269.

Craig, B. A., Morton, D. P., Kent, L. M., Gane, A. B., Butler, T. L., Rankin, P. M., et al. (2018). Religious affiliation influences on the health status and behaviours of students attending Seventh-day Adventist schools in Australia. Journal of Religion and Health,57, 994–1009.

Dezutter, J., Soenens, B., & Hutsebaut, D. (2006). Religiosity and mental health: A further exploration of the relative importance of religious behaviors vs. religious attitudes. Personality and Individual Differences,40, 807–818.

Dilmaghani, M. (2018). Importance of religion or spirituality and mental health in Canada. Journal of Religion and Health,57, 120–135.

Doane, M. J., & Elliott, M. (2016). Religiosity and self-rated health: A longitudinal examination of their reciprocal effects. Journal of Religion and Health,55, 844–855.

Eliassen, A. H., Taylor, J., & Lloyd, D. A. (2005). Subjective religiosity and depression in the transition to adulthood. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion,44, 187–199.

Ellison, C. G. (1991). Religious involvement and subjective well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior,32, 80–99.

Ellison, C. G. (2010). Race, religious involvement, and health: The case of African Americans. In C. G. Ellison & R. A. Hummer (Eds.), Religion, families and health: Population-based research in the United States (pp. 321–348). New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Ellison, C. G., Boardman, J. D., Williams, D. R., & Jackson, J. S. (2001). Religious involvement, stress, and mental health: Findings from the 1995 Detroit area study. Social Forces,80, 215–249.

Ellison, C. G., Gay, D. A., & Glass, T. A. (1989). Does religious commitment contribute to individual life satisfaction? Social Forces,68, 100–123.

Francis, L. J., & Kaldor, P. (2002). The relationship between psychological well-being and Christian faith and practice in an Australian population sample. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion,41, 179–184.

Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2002). What can economists learn from happiness research? Journal of Economic Literature,40, 402–435.

Gautherier, K. J., Christopher, A. N., Walter, M. I., Mourad, R., & Marek, P. (2006). Religiosity, religious doubt, and the need for cognition: Their interactive relationship with life satisfaction. Journal of Happiness Studies,7, 139–154.

Green, M., & Elliott, M. (2010). Religion, health, and psychological well-being. Journal of Religion and Health,49, 149–163.

Greenfield, E. A., & Marks, N. F. (2007). Religious social identity as an explanatory factor for associations between more frequent formal religious participation and psychological well-being. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion,17, 245–259.

Headey, B., Schupp, J., Tucci, I., & Wagner, G. G. (2010). Authentic happiness theory supported by impact of religion on life satisfaction: A longitudinal analysis with data for Germany. The Journal of Positive Psychology,5, 73–82.

Keyes, C. L. M., & Reitzes, D. C. (2007). The role of religious identity in the mental health of older working and retired adults. Aging & Mental Health,11, 434–443.

Kortt, M. A., Dollery, B., & Grant, B. (2015). Religion and life satisfaction down under. Journal of Happiness Studies,16, 277–293.

Larson, D. B., & Larson, S. S. (2003). Spirituality’s potential relevance to physical and emotional health: A brief review of quantitative research. Journal of Psychology and Theology,31(1), 37–51.

Lewchuk, W., de Wolff, A., King, A., & Polanyi, M. (2003). From job strain to employment strain: Health effects of precarious employment. Just Labour,3, 23–35.

Lim, C., & Putnam, R. D. (2010). Religion, social networks, and life satisfaction. American Sociological Review,75, 914–933.

Lyons, A. C., & Yilmazer, T. (2005). Health and financial strain: Evidence from the survey of consumer finances. Southern Economic Journal,71, 873–890.

Mirowsky, J., & Ross, C. E. (1992). Age and depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior,33, 187–205.

Ngamaba, K. H., & Soni, D. (2018). Are happiness and life satisfaction different across religious groups? Exploring determinants of happiness and life satisfaction. Journal of Religion and Health,57, 2118–2139.

Nooney, J., & Woodrum, E. (2002). Religious coping and church-based social support as predictors of mental health outcomes: Testing a conceptual model. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion,41, 359–368.

Plomin, R., Scheier, M. F., Bergeman, C. S., Pendersen, N. L., Nesselroade, J. R., & McClearn, G. E. (1992). Optimism, pessimism and mental health: A twin/adoption analysis. Personality and Individual Differences,13, 921–930.

Pollner, M. (1989). Divine relations, social relations, and well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior,30, 92–104.

Rizvi, M. A. K., & Hossain, M. Z. (2017). Relationship between religious belief and happiness: A systematic literature review. Journal of Religion and Health,56, 1561–1582.

Scheier, M. E., & Carver, C. S. (2006). Dispositional optimism and physical well-being: The influence of generalized outcome expectancies on health. Journal of Personality,55, 169–210.

Schnittker, J. (2001). When is faith enough? The effects of religious involvement on depression. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion,40, 393–411.

Şenel, E. (2018). Health and religions: A bibliometric analysis of health literature related to Abrahamic religions between 1975 and 2017. Journal of Religion and Health, 57, 1996–2012.

Sethi, S., & Seligman, M. E. P. (1993). Optimism and fundamentalism. Psychological Science,4, 256–259.

Sinnewe, E., Kortt, M. A., & Dollery, B. (2014). Religion and life satisfaction: Evidence from Germany. Social Indicators Research,123, 837–855.

Strawbridge, W. J., Shema, S. J., Cohen, R. D., & Kaplan, G. A. (2001). Religious attendance increases survival by improving and maintaining good health behaviors, mental health, and social relationships. Society of Behavioral Medicine,23, 68–74.

Suhail, K., & Chaudhry, H. R. (2004). Predictors of subjective well-being in an Eastern Muslim culture. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology,23, 359–376.

Ware, J. E., Snow, K. K., Kolinski, M., & Gandeck, B. (1993). SF-36 Health Survey manual and interpretation guide. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Centre, Boston, MA.

Wink, P., Dillon, M., & Larsen, B. (2005). Religion as moderator of the depression-health connection: Findings from a longitudinal study. Research on Aging,27, 197–220.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bernardelli, L.V., Kortt, M.A. & Michellon, E. Religion, Health, and Life Satisfaction: Evidence from Australia. J Relig Health 59, 1287–1303 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-019-00810-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-019-00810-0